No one can make you feel anything

The belief that we have total control over our responses to other people and can determine entirely the impact they have on us is surprisingly widespread. Dr Kate Wachs summarises the position as follows:

‘Just as money can’t make you happy, other people can’t make you happy either. No one can make anyone think or feel or do anything. The only person who has that distinction is the person who owns the thoughts, feelings, and behaviour. When you accept this truth, then and only then can you be truly happy.’

The view expressed here is no longer the preserve of wibbly self-help books – now it’s commonplace in management development coaching. Nearly all of us must have had the startling revelation that ‘no one can actually make you feel anything’ bestowed upon us, often in tones of eye-watering sincerity, by well-meaning friends, partners or the latest self-help blockbuster.

This has surely got to be one of the most ludicrous propositions in the whole of popular psychology. To add insult to injury, this absurd gobbet of enlightenment is invariably delivered up in such sanctimonious tones that it makes me, for one, feel all kinds of things – the uppermost of which is a desire to grab the collar of the person dispensing it and scream: ‘Have you actually spent any time in the company of real people?’

Of course people make us feel things: I challenge you to name one significant emotional peak or trough in your life that does not have something to do with your reactions to a fellow human being. The entire history of our species is a millennia-spanning testimony to the profound impact we have on one another at all kinds of levels, many of which we have precious little conscious control over. The degree to which we are affected and influenced by other people is actually quite terrifying, but equally disquieting is our collusion with the rather smug fantasy that we are fundamentally untouchable, and that we are capable of orchestrating our own reactions to every encounter.

Okay, so I am being slightly unfair. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) has successfully demonstrated over numerous clinical trials that teaching people to reinterpret their experiences can indeed have a beneficial knock-on effect on their emotions, and this is precisely the point that Dr Wachs is trying to make. If I believe my boss has it in for me I am likely to perceive her performance review as overly critical and nit-picking; if, on the other hand, I believe she likes me and is genuinely trying to help, I will respond to her advice as constructive criticism and leave the room with a smile on my face instead of elevated blood pressure. As thinking creatures we do have some choice about how we frame events, and of course this does influence how we subsequently feel about them.

In fact there is evidence that just the very process of thinking things through can turn down the intensity of our emotional responses. In California at the turn of the century Ahmad Hariri and colleagues found that when people were simply asked to label the expressions on faces (in other words engage in some intellectual processing of what they were seeing) their MRI scans showed reduced blood flow in the fear centres of the brain and a corresponding increase in the prefrontal cortex, the area that helps us regulate our emotional reactions. Keeping a cool head, thinking things through, trying to be objective – all of these things can genuinely help us to some degree.

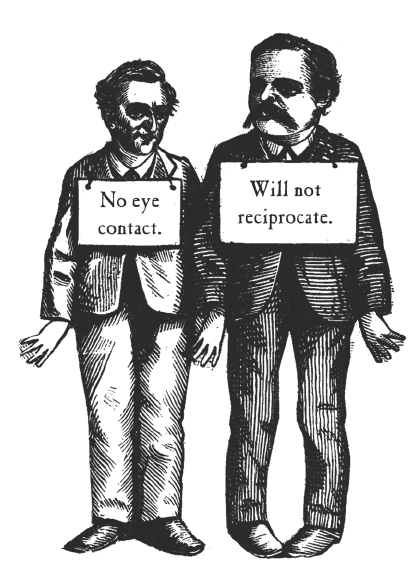

Remember: no one can make you feel anything ...

However, while the techniques of CBT have undeniably helped countless thousands of people, we are usually talking about damage limitation after the event. In the moment, our reactions tend to be instantaneous, unbidden and emotionally charged. It takes time and a great deal of dedicated practice to reprogramme our automatic responses to certain stimuli. The prospect that our rationality is a fire extinguisher capable of dampening down every unwanted emotion may be comforting, but it is largely a fantasy.

Reason can only help us so far because so much of what is transacted between human beings affects us at an entirely unconscious or instinctual level. For example, say you have done your grocery shop and are just about to leave the car park when you see someone else waiting for your space. Being the kind, helpful person you are you would naturally be as quick as you can to vacate the space so the next customer can occupy it. This is certainly what most people say they would do. However, the reality is that people who are conscious of someone waiting to take their space actually take slightly longer to leave than when no one else is around. We know this because Barry Ruback and Daniel Juieng conducted a series of experiments demonstrating precisely this phenomenon in 1997. Similarly, in another of Ruback’s experiments men were found to linger longer in library aisles when joined by a male confederate. Even as supposedly civilised people we are still in thrall to ancient territorial instincts that continue to determine our behaviour, even though we may be completely oblivious to them.

Moreover, while we may think we are in control of our responses, it appears that we are very easily cued into behaving in ways that conform to other people’s expectations of us without even realising it. In 1977 at the University of Minnesota Dr Mark Snyder and colleagues conducted an ingenious experiment that showed just how powerful this effect can be. A group of men were asked to hold phone conversations with women after they had been given a photo of a woman who had been judged either highly attractive or frankly rather plain by independent raters. The study set out to explore the impact of the stereotype that physical attractiveness is associated with other positive qualities such as intelligence, kindness, sociability and so on. What was fascinating was that the women, irrespective of how attractive they actually were, responded in keeping with the expectations of the man they were talking to: the men who thought they were talking to an attractive woman ended up having conversations with women who were independently rated as being far more sociable, poised, sexually warm and outgoing. As the authors of the research concluded: ‘What had initially been reality in the minds of the men had now become reality in the behaviour of the women with whom they had interacted – a behavioural reality discernible even by naive observer judges, who had access only to tape recordings of the women’s contributions to the conversations.’

An even more graphic example of our tendency to conform instinctively to the roles that others create for us is the behaviour of the subjects in Stanley Milgram’s experiments who administered what they believed to be dangerously high levels of electric shocks to other people just because a man in a white coat told them to. Or what about the behaviour of the students randomly allocated to play the role of guards in the infamous Stanford prison experiment conducted in the seventies? These young men, all of whom had been psychologically evaluated as well-balanced and intelligent beforehand, obligingly fell into role and produced some truly sadistic behaviour, punishing their pretend prisoners in ways strongly reminiscent of more recent images from Abu Ghraib. We may think we would be immune, but as one of the student guards retaliated to a hostile audience during questions at the end of a lecture about Zimbardo’s experiment: ‘Can you say for sure that you would have done any different?’ We may like to think we can control our actions and reactions in the way popular psychology assures us we can, but as Yale psychologist John Bargh reminds us, people are reluctant to recognise how much of their everyday experience ‘is determined not by their conscious intentions and deliberate choices, but by mental processes put into motion by their environment’. In other words, we may think we’re calling the shots, but most of the time we are not even aware of the extent to which we are being unconsciously cued into particular roles by the actions and behaviour of those around us. How we experience the world, and even how we experience ourselves, is largely determined by others.

On a more upbeat note, these invisible tendrils of social influence can produce positive effects too. Dr Robert Rosenthal reports on an experiment in which students were allocated to two classes. The teacher of one was told that the children in that class were gifted and exceptionally able, while the other was informed that her class was made up of children who were underachievers and likely to need extra help. In fact at this point there was no difference in the average ability of either class. However, lo and behold, by the end of the year the students in the ‘gifted’ class were indeed outperforming their peers while the underachievers became precisely that.

Further evidence of the way other people automatically condition our responses to them has come from Alex Pentland’s ‘reality mining’ studies at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). By equipping subjects with modified smart phones which recorded data regarding aspects of their non-verbal communications (including proximity, tone and posture), the MIT team have demonstrated a subliminal level of interaction taking place between people that turns out to be a far more reliable index of what’s really going on between them than the superficial content of their conversation. We are not only highly attuned to these ‘honest signals’ but they powerfully influence our behaviour and mood, again without us even being aware of it. As Pentland explains, ‘honest cues are also unusual because they trigger changes in people receiving the signals, changes that are advantageous to the people who send them.’ So potent is this second channel of communication that by observing the first five minutes of a mock salary negotiation, judges on the lookout for the relevant subliminal behaviours were able to predict with an 87 per cent accuracy who would come out on top.

One aspect of non-verbal communication that Pentland’s team have focused upon is the non-conscious mimicry that tends to occur automatically when people spend time in each other’s company. Various studies have confirmed that people tend to copy each other’s body language, facial expressions, speech patterns and vocal tones. The reason this automatic mimicry is crucial in understanding social influence is because psychologists believe it may be one of the mechanisms that underlie emotional contagion, i.e. the ability of one person to transfer emotions to another. What we do with our bodies has a direct impact on the emotions we experience. Smile (even though your heart is breaking) and science suggests you will indeed feel better. Slump in your seat and your mood is more likely to become listless and despondent. In fact this feedback mechanism is so effective that researchers from the University of Cardiff found that women whose ability to frown was inhibited after receiving botox injections reported feeling much happier and less anxious – even though they believed the procedure hadn’t significantly improved their appearance!

Be on the lookout for those subtle body-language clues ...

It seems likely that by unconsciously copying the behaviour and micro-expressions of people around us we consequently end up replicating their emotions. In fact, research has established that even feelings like loneliness can be catching. A careful investigation conducted in Framingham, Massachusetts found that if even one person in a neighbourhood felt lonely for one day a week, the level of perceived loneliness across the neighbourhood also rose. More dramatic examples of contagion would be the kind of mass hysteria you see sweep across crowds, or the tragic events that took place in another Massachusetts town, Salem, in 1662 when a number of teenage girls were tried as witches after replicating each other’s screaming and convulsions so closely that a local minister decided they were ‘beyond the power of epileptic fits or natural disease to effect’.

It is not only through the subconscious power of imitation that we are exposed to the emotions of those around us. It turns out that we are neurologically configured to connect up with what others around us are experiencing. In recent years scientists have discovered specialised mirror neurones in the brain that effectively put us into the other person’s shoes. Simply watching someone kicking a ball fires up the motor centres of our own brains that would be involved if we were the ones doing the kicking. But it also appears to be true of emotions as well. When we see someone upset, mirror neurones trigger a sympathetic activation of our own emotional processing centres. Far from other people not being able to make us feel anything, we are in fact hard-wired in ways that predispose us to feel their pain or share their joy.

Mirror neurone research suggests there is substantial psychological mileage in the old adage that ‘we become like the company we keep’. Whether this is pleasurable, enlightening, soothing or discordant depends on a host of interpersonal variables. Other people can expose us to the best and the worst in ourselves. They can transport us to delirious emotional heights but, as Sartre pointed out, they can also take us straight to hell. However, it is certainly naive to assume that we are in full control of the emotional impact of such encounters.

Far from relying upon the dodgy adage that no one can make us feel anything we don’t allow, instead we should recognise just how vulnerable and open we are to the invisible and unconscious influence of those around us. We would be well advised, therefore, to make thoughtful choices about the company we keep or, as the silent movie star Louise Beal astutely put it: ‘Love thy neighbour as yourself, but choose your neighbourhood.’

We should also be mindful of our own impact on others. We’ve seen that other people can’t necessarily choose how to respond to us. So how we are around other people really matters – yet this is rarely, if ever, the subject of any self-help guru. They and we naturally attend to the way other people leave us feeling, but how much do we reflect upon the way we can change the atmosphere in a room or how our manner affects other people? In years to come I suspect we will no longer think about pollution as merely what happens when you pump toxic fumes into the atmosphere or fail to recycle domestic waste. While physical waste is obvious to us all, ‘emotional pollution’ is no less of a real issue. Its cumulative effects can be significant. As the eco-campaigners would say: we all need to take responsibility for ensuring we are part of the solution and not part of the problem.

Of course, you might also want to question whether you might not want to allow other people to make you feel things from time to time. Rumour has it that other people can sometimes make you feel pretty good. Even when they don’t, while it might be prudent to keep those feelings to yourself sometimes, our spontaneous internal reactions to the people around us and the things that happen to us are an important part of being fully alive. Surely we’re not now aspiring to be emotionally vacant Stepford Wives who sail through life’s twists and turns completely unruffled, with never a hair out of place? Other people will always have the capacity to make us laugh and cry. They can light us up with joy one moment and cast us into despair the next. That’s just how it is. And to be honest, would we really want it any other way?