Introduction

WHAT’S SO WRONG WITH POPULAR PSYCHOLOGY ANYWAY?

We live in the age of self-improvement. As we go about our daily lives we are subjected to a million messages – some subtle, and some less so – intimating that a happier, richer, more successful life is just around the corner. With the immediate survival needs of food and shelter taken care of for the majority, western civilisation has now turned its attention to how much better it could all be. And this in turn has spawned a prolific, multi-million dollar industry of stadium-filling gurus, bestselling books, magazines and websites telling us how to be happier, thinner, richer, and all round better people. But is our culture of self-help really helping? Or is it just creating expectations that none of us can live up to? Has the casual psychologising of everyday life enlightened us, or are we just making a rod for own backs?

These are questions we all need to be grappling with. This book is an invitation to pause, take stock, and maybe start weeding out some of the more insidious modern myths that have taken root in our collective psyche. I’m not simply trying to be a killjoy or score cheap points at other people’s expense. I fully appreciate that many contributors to the burgeoning self-help industry are sincere, well-intentioned individuals who genuinely want others to benefit from their wisdom and experience. The majority are not charlatans out to make a quick buck from our credulity. Some are well-informed and well-qualified to offer advice, and such people absolutely deserve to be listened to. However, insofar as this does feel like a grumpy tirade, it’s because I am increasingly concerned that something significant is happening within our society to which we continue to turn a naively blind eye.

It’s too easy to dismiss the world of self-help as an amusing diversion, a quick read on the plane or a pleasant escapist fantasy of a life reinvented and transformed. Maybe we might even pick up a few handy tips or a couple of insights along the way. What’s the harm? After all, nobody takes these things that seriously, do they? But the truth is that secretly many of us do. Increasing numbers of us are turning to the pages of self-help books in search of answers to lives that feel in need of fixing. The phenomenal growth of the self-help sector in the last century is a testament not only to our rising levels of insecurity and self-doubt, but to the stealthy psychologising of our culture as a whole.

The ideas and values associated with popular psychology have infiltrated our culture so deeply that we now take them largely for granted. Even for those of us who regard ourselves as fairly knowing, they form part of that framework of assumptions that constitutes the invisible scaffolding for the way we approach our lives. They shape our evaluations of other people and ourselves. They subtly colour the tone of everyday experience, bringing with them an agenda that radically affects the kinds of decisions and choices we make both as individuals and as a society. Rather alarmingly, much of this has taken place without us ever having paused to examine these precepts, or to question whether we can afford to follow where they lead. Whilst we may like to think that popular psychology holds up a mirror that allows us to understand ourselves, it is also a distorting mirror that remakes us in its own image. In The Selfish Gene, Richard Dawkins introduced us to the meme, defined as ‘an idea, behaviour or style that spreads from person to person within a culture’. Thanks to the powerful engine of the self-help industry, the memes of popular psychology are busy replicating themselves so effectively that they have become an integral part of the fabric of our lives and thought processes.

Consider, by way of illustration, the popularity of talent shows like The X Factor. The format dictates that every contestant must undergo a journey of personal transformation. Their motivations are accounted for in terms of an emotive back story that usually implies some cod-psychological rationale for their decision to audition while the audience is invited to nod (and vote) approvingly as contestants ‘grow’ as artists and people over the ensuing weeks. Shania is a natural talent but ‘just needs to believe in herself more’. Ricky could be world-class but needs to get in touch with who he really is inside if he is ever to give a truly ‘authentic’ winning performance. And Cassie could be great if she ever manages to let go of those emotional demons from her past.

Under the guidance of mentors whose assertive sound bites would make many motivational speakers blush, the contestants are prompted to change their lives and take charge of their fates. If they can just believe hard enough, give it 110 per cent, focus on their goals and ‘stay in the zone’, then maybe that elusive recording contract will be theirs. However, all the while the pseudo-psychological lore of such shows whispers in our ear that the true prize on offer is not the record contract but the personal fulfilment awaiting anyone brave enough to try and ‘live their dream’.

You can dismiss this all as good storytelling by the production company but these format points are also an indication of the extent to which popular psychology and popular culture have become intimately fused. Psychobabble is a language that, like it or not, we are all learning to speak fluently, and elements of those Saturday night prime-time shows could have been lifted straight from the pages of the countless self-help books that line the shelves of your local bookstore, not to mention the CDs purchased and training courses attended by millions of us every year.

The most successful self-help books have a long reach: classics like How to Win Friends and Influence People and I’m OK, You’re OK are said to have sold 15 million copies worldwide. You Can Heal Your Life by Louise Hay has sold over 35 million, while Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus and the Chicken Soup for the Soul series claim over 50 million and 100 million sales respectively. These are big numbers in the publishing world. If you are reading this you will almost certainly have heard of these books and probably have a fair idea of what is in them. But even if you haven’t, you will still have been affected by them.

The congregational minister Edwin Paxton Hood once admonished: ‘Be as careful of the books you read, as of the company you keep; for your habits and character will be influenced as much by the latter as by the former.’ Perhaps we should be taking his advice to heart. The values and preoccupations of popular psychology are already profoundly influencing the nature of the stories we tell ourselves about who we are and who we can become. The question we need to ask is, when we take a cold hard look at the outcome, do we really like what we see?

KEEPING IT SIMPLE

One of the major selling points of any good self-help book is actually one of the most misleading, namely the promise that it will distil a potentially complex situation or life challenge into a manageable and readily digestible form. This would be great if it were remotely possible. As you may have noticed as you have fumbled along through the years, human beings are complex, their lives are complex, and the social environment they are trying to navigate is complex. There are innumerable variables involved in even the most simple of human activities. As the new branch of science known as ‘chaos theory’ has been amply demonstrating over recent years, even small local variations can produce a truly bewildering variety of outcomes – so great in fact as to render prediction virtually impossible, even in a closed, deterministic system.

The virtue of parsimony enshrined in Occam’s razor – the principle that a simple explanation or theory is usually preferable to a complex one – is all very well, but as our understanding of the world grows more sophisticated we are being forced to acknowledge that even the most economical explanations at our disposal are not necessarily straightforward. It turns out Oscar Wilde was right when he wrote: ‘The truth is rarely pure and never simple.’ For example, in the mysterious world of particle physics, Superstring Theory remains the most promising candidate to provide us with a workable ‘Theory of Everything’. This is the Grail of modern physics, the theoretical framework that will finally allow physicists to reconcile the uneasy bedfellows of quantum physics and general relativity. However, as Brian Greene points out in The Elegant Universe, although the theory looks sound, the maths involved is proving so complex that even the best mathematical brains in the world are currently struggling to make the highly convoluted sums add up.

Understanding the way inert matter behaves is hard enough, but when we start trying to understand ourselves we have a truly momentous task on our hands. As David Rogers explains: ‘The most extensive computation known has been conducted over the last billion years on a planet-wide scale: it is the evolution of life. The power of this computation is illustrated by the complexity and beauty of its crowning achievement, the human brain.’ If, as Rogers claims, we are sitting at the apex of some notional pyramid of complexity, the chances that we will ever understand ourselves in any depth are pretty remote. After all, it is not even as if every human brain is identical or even running the same software. I would furthermore suggest that the chances that any significant aspect of our multifaceted, multidimensional and highly idiosyncratic lives (especially those murky unresolved zones we tend to demarcate as ‘problems’) can ever be covered adequately by a brace of simple rules, five key principles or seven effective habits, are practically next to zero.

Yet this is precisely what the bulk of self-help books offer. Many popular-psychology authors and publishers even exalt in the fact. Take Norman Vincent Peale for example, the father of positive thinking, who berates us for ‘struggling with the complexities and avoiding the simplicities’. This would be all very well if life were simple, but if the maps we are using to guide us aren’t sufficiently detailed to do justice to the terrain we are traversing we shouldn’t be surprised if we go astray. The American editor and social commentator H. L. Mencken pointed out the dangers inherent in oversimplification when he quipped sarcastically that ‘For every problem there is a solution which is simple, clean and wrong’. Popular-psychology authors take note! The subtle eddies of the mind and heart are not some pan of stock that can be reduced to its concentrated essence – at least not without leaving a pretty bitter taste in our mouths.

Ironically, of course, the appetite for these absurdly simplified models of our complex lives is greatly enhanced by the fact that modern life is becoming increasingly hard for us to get our heads around. We move constantly between different contexts; in turns we play the roles of parent, partner, colleague, friend, carer, leader, member of the community, to name but a few. The rampaging growth of information technology now means that we are bombarded with more information and more competing demands on our attention than ever before. We are drowning in choice.

The need to organise this chaotic flow of experience, to impose some kind of order on unruly chaos, is thus a universal and pressing one. We all need concepts that allow us to carve reality up into manageable chunks and impose a framework of understanding and predictability on our experience, but we need to choose the right ones. As the mythologist Joseph Campbell pointed out (and it is to Campbell, ironically, we owe that ultimate self-help maxim: ‘Follow your bliss’), every society needs its myths to stabilise the treacherous, swirling vortex of reality. In our modern world, successful self-help books are almost certainly filling the gap left by the ebbing tide of religious faith.

However, a major drawback of the world of Psychobabble is that the categories on offer are usually a good deal less sophisticated or flexible than your average zodiac sign. Our craving for order is so urgent that we cheerfully embrace two-dimensional classifications that leave us constantly trying to jam round pegs into square holes. We eagerly latch onto those features of our partner that just go to prove they are indeed from Mars or Venus or wherever, while mentally binning aspects of their behaviour that don’t fit the stereotype. Are you an extrovert or an introvert, a thinker or a feeler, a type A or a type B, a permissive parent or an authoritarian one? How many of us have completed a personality questionnaire which required us to choose between discrete alternatives, all the while thinking, ‘But sometimes I’m like this, while on other occasions I am more like this ...’? There is little room for such fuzziness or ambivalence in Psychobabble’s brave new world.

While claiming to educate and enlighten us, Psychobabble continually dumbs us down. Rather than attending to the exceptions and contradictions that might indicate the need to review our assumptions (which is how real science generally proceeds), we satisfy ourselves with a blinkered vision of reality because it feels safer. As George Orwell warned us in his novel 1984, overly rigid systems of thought or ‘restricted codes’ are the best way to shut down new possibilities of thought and self-awareness. How ironic then that an industry devoted to helping people grow and explore human potential actually offers a conceptual vocabulary so limited that it effectively restricts opportunities for self-discovery and the articulation of our individuality. If we become too fluent in Psychobabble we risk losing the ability to express or maintain contact with what makes each life truly unique.

WHY DON’T WE FEEL BETTER YET?

As Mencken points out, the trouble with overly simple solutions is that they often don’t work too well in the real world. Whilst our psychological mythologies may provide us with a welcome emotional security blanket in the short term, as technologies for producing any kind of sustained change in the long term the techniques recommended in so many self-help books are likely to come up empty. How many of our lives have been truly transformed by what we have read or heard? You may have felt inspired at the time but how many of us are now slimmer, sexier, richer, more confident or successful than we were before we shelled out our hard-earned cash on the latest book or course that was going to revolutionise our lives?

I’m not saying that all self-help books are a waste of time – I think some are genuinely helpful – but in my experience their long-term impact tends to be directly proportional to the extent to which their insights and recommendations are based on valid research. Science certainly isn’t without its limitations and experiments are only as good as their design, but when it comes to knowing things about the world, scientific enquiry is probably the best way of proceeding that’s currently available.

Psychology has always posed a particular challenge for science since it has to concern itself with slippery concepts like meaning and value as well as more readily measurable commodities like behaviour or brain activity. Formal psychology is also a mere babe amongst the sciences: not even 150 years have passed since Wilhelm Wundt first set up his laboratory in Leipzig to try and investigate consciousness in a systematic fashion. It’s therefore hardly surprising we still don’t know that much about the mysterious workings of the mind; considerably less, in fact, than the applied disciplines of clinical psychology and psychiatry would have you believe. What we do know inevitably coincides with the areas of mental activity most accessible to testing and observation: domains like memory, perception, and reasoning. Once we get into the stuff that preoccupies most of us on a daily basis (i.e. how to navigate our relationships, further our careers, manage our moods, raise our kids and so forth) we drift ever further into the woods of speculation. We also need to recognise that many of these key aspects of our lives are socially constructed. They are matters of preference and societal value, simply the way we do things around here rather than anything written into our DNA. When it comes to understanding the human mind, sometimes there are questions to which there are no right and wrong answers. Nevertheless, we are getting better at testing out and measuring what people perceive to be working for them and what actually improves their quality of life.

We should therefore not be too surprised when we discover that the helpful techniques and well-meaning advice don’t necessarily deliver the changes they promise. The bottom line is that often the techniques don’t work simply because there is no reason (apart from the enduring power of placebo) why they should. There is precious little quality control in the world of self-help, where conviction is all too often a willing stand-in for reasonable proof. The biologist Thomas Huxley once opined gravely that ‘The deepest sin against the human mind is to believe things without evidence.’ If he is right, then the self-help section of your local bookstore is a veritable den of iniquity.

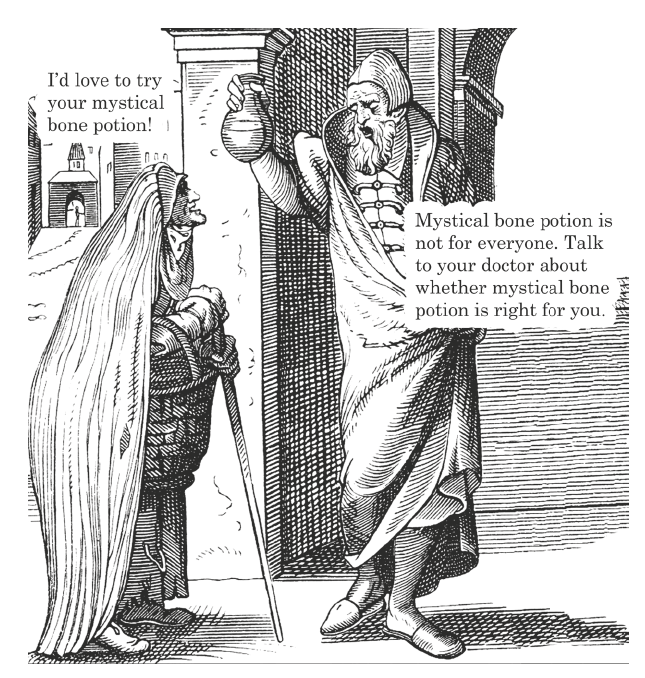

We may roll our eyes at the medical practices of times gone by, when drilling holes in people’s heads was seen as the best way of letting out the demons, cupping could rebalance the humours, or rubbing the corpse of a bisected puppy into the skin of a victim was the state-of-the-art cure for bubonic plague. But while contemporary remedies for the mental and emotional ills of our age may be less dramatic, many of our own psychological cures and theories boast scarcely more respectable scientific credentials.

Perhaps the deal is that in order to remain accessible to a broad audience, ‘popular’ psychology has to restrict itself to ideas that not only capture the public imagination, but also avoid placing an excessive burden on the public understanding. The technicalities of research methodology, the mysteries of multiple regression and double-blind trials, the difficulty of evaluating the significance of results which may vary from study to study; none of this is exactly sexy. And at the end of it all, of course, your best outcome is only a tentative balance of probability, another provisional hypothesis waiting to be disproved. Perhaps we can excuse ourselves for wanting to scroll down to the punch-line, however ill-informed, caveat-ridden and ineffectual it may turn out to be.

Should all self-help books carry a health warning?

The danger is that it is consequently very easy for popular-psychology authors to blur the boundaries between opinion, ideology and reputable fact. It is increasingly in vogue for self-help authors to enlist the backing of scientific studies to support their views, but while the results may look like science and sound like science, because popular psychology is effectively ‘science lite’ the quality of the studies cited is seldom evaluated and contradictory evidence rarely considered.

In the Melanesian archipelagos of the southwest Pacific, shortly after WWII, anthropologists became aware of a strange phenomenon taking place amongst the indigenous islanders. In Papua New Guinea, for example, natives were found clustered in the forest around a roughly hewn model of an airplane complete with its own airstrip, gazing expectantly at the skies and waiting devoutly for deliverance. These islanders were members of what became known as a ‘cargo cult’, a religious movement in which less technologically developed societies integrate the products and processes of more ‘advanced’ industrialised cultures into their religious rituals and beliefs. This often resulted in tribes imitating the procedures and processes associated with this benevolent technology, but without real understanding of the function of the behaviour they were copying.

It was with reference to such practices that in his address to the Californian Institute of Technology in 1974, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman warned against the dangers of ‘cargo cult science’, in other words, behaviour that looks scientific on the surface but doesn’t actually follow the stringent protocols of proper scientific method. Popular psychology, it seems to me, is particularly vulnerable to such a charge, since scientific theories and precepts are often twisted to serve the purposes and fit the belief systems and values of the self-help gurus. Let’s just say that if I have to read one more vague allusion to Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle to justify the idea that the mind can directly influence events in the material world, I may not be responsible for my actions ...

The enterprise of Psychology is challenging enough but, given how difficult it is for us to know anything about ourselves, it seems particularly important that we don’t start building our house on sand. There are many ways of knowing, and science is only one of them, but when it comes to establishing what will work reliably in the real world it is often hard to beat. Psychobabble may sound rational enough but often it is the discourse of superstition as much as it is of sense. It creates unrealistic expectations that ultimately lead to disappointment and disillusionment. Life is hard enough without chasing empty promises or kidding ourselves to expect the impossible. Perhaps we owe it to ourselves to try and evaluate systematically what’s on offer, and what it can do for us, rather than grabbing at false hope because it temporarily alleviates our pain.

IT’S ALL ABOUT YOU!

We do ourselves no favours when we start mistaking theories as facts or confuse wishful thinking with reality. However, perhaps the most compelling objections to the world of popular psychology lie not with its truth claims but with its morals. Psychobabble seems to pander to some fairly ignoble aspects of ourselves, or at least to the most regressed. Not only is its worldview childlike in favouring simplistic, black and white solutions to complex problems, but its core values are too. When it boils down to it, most self-help books address fairly rudimentary drives: stop it hurting; give me what I want; make me more powerful. While there is nothing inherently wrong with these instincts, I would politely venture to suggest that they don’t really amount to a manifesto for a grown-up life.

Copernicus may have successfully booted Earth from the heart of the cosmos but Psychobabble places each of us back at the very centre of the world. Just as we may go to the gym to sculpt our bodies, Psychobabble offers us tools to primp and preen our lives, to edit our personal biographies into something more pleasing. It encourages us to become self-absorbed narcissists, perennial teenagers for whom the world barely exists beyond themselves. If, as conventional therapeutic wisdom insists, we have to ‘learn to love ourselves first’, is it any wonder we are not always that aware of anyone else around us? There are plenty of titles showing us how to develop the social skills to attract friends or influence people, but where are the equivalent books showing us how to be a good friend, or develop the skills and attitudes that might enable us to become more altruistic or serve our communities better? With our focus fixed eternally on our own personal development, self-enhancement, and the constant upgrading of our own lives, we are condemned to an eternal childhood of self-absorption.

While Psychobabble stokes our society’s overbearing sense of entitlement, it also places us under increasing pressure. It encourages us to reference unrealistic baselines by insisting, for instance, that happiness is the normal state of human existence. Consequently, if we do find ourselves feeling unhappy or shy or frightened, our response is to feel that something is badly wrong that must be fixed as soon as possible. There is little room for the notion that these experiences might be legitimate, or ordinary, or have something important to teach us. We end up pathologising routine aspects of everyday life.

The self-help section of your local bookstore is actually a Bill of Rights in disguise, and it sets the bar pretty high. Let’s not forget, you deserve to be happy, accomplished and beloved – just like everyone else. After all, you’re worth it! With such messages beamed at us every day in subtle and not-so-subtle forms, is it any wonder that people feel angry or ashamed when their lives don’t measure up, or that they can get so preoccupied with trying to get things back on course?

The underlying imperative behind so much popular psychology is the need for constant change. By teaching us to structure our experience exclusively in terms of problems (or ‘challenges’) and solutions, the self-help industry keeps us on a never-ending treadmill. There is no sense that you can relax, that things might actually be good enough as they are, or that even if they aren’t so great right now, this might be something to be tolerated and endured rather than fixed. Although I suspect he was referring to the problems of the Middle East (in which case, depending on your political persuasions, you might view this as something of a cop-out), the Israeli politician Shimon Peres once said something profoundly true: ‘If a problem has no solution, it may not be a problem, but a fact – not to be solved, but to be coped with over time.’ However, popular psychology is having none of that. Instead it feeds off our dissatisfaction with ourselves and our lot. It tells us not only that things can be improved, but that it is our responsibility to improve them.

This is a lot of pressure for any normal, flawed human being to accommodate. I remember browsing the self-help section of my local bookstore one sunny afternoon and rapidly feeling overwhelmed. There was just so much to do; so many areas of my life apparently in need of urgent attention. If I were to awaken the giant within, familiarise myself with the rules of life, become highly effective, lose 40 pounds and embrace a more confident, happier, assertive, creative, focused, flowing and decisive version of myself I clearly had my work cut out. Where was I going to find the time for all this? Perhaps what I needed was a book that would teach me to speed-read or give me some top tips on managing my time more effectively? Surveying the vast amount of help out there it’s easy to feel like a gardener who returns from a long vacation to discover that their whole plot is completely overrun by weeds.

We all like to pretend that we are wise to the game, that being sophisticated souls we are immune from the grandiose claims of the popular-psychology market but, come January, how many of us will be sneaking out with the latest fad diet book under our arm, even if it is discreetly shrouded in a suitable bag? The trouble is that it is only human nature to turn the enticing notion that we could be better into the nagging conviction that we should be better. All these books to which we turn in order to feel good about ourselves can very easily end up making us feel worse. A faint whiff of the Aryan suffuses the whole enterprise. Our weakness and vulnerability must be expunged; only a pristine or radically revised version of ourselves is ultimately acceptable. Self-improvement is a duty. Don’t you dare let me catch you being less than the Best Possible You! No wonder we feel tired. Isn’t it about time we stopped allowing ourselves to be bullied by those who say they are trying to help us?

I will admit upfront that I am about to start lobbing stones from the glassiest of houses. As a practising clinical psychologist I am a fully paid-up member of the change industry and painfully conscious that over the years my clients have heard a constant stream of Psychobabble issue from my own lips. Even worse, I have written self-help books myself. While I hope they are not the worst examples of their kind, I am sure I have taken liberties with the science and will probably do so again in the pages that follow, so you had better keep your wits about you.

I am inviting these accusations of hypocrisy because I really do believe this is important. I am increasingly weary of some of the nonsense that is put about in the name of psychology and the subtly debasing effect it has on us and our culture. It’s about time we all adopted a much more robust and critical attitude towards the whole business. Myths of all kinds certainly have their place in our society and I personally believe they are sometimes vehicles for deep truths that cannot be expressed adequately in other forms. However, in the spirit of calling a spade a spade, let’s be clear about what we are dealing with: Psychobabble isn’t the language of a rich mythic tradition that can unify us within the enclave of a common sacred story; it is often lazy pseudoscience that ought to be robustly interrogated so we can see what’s real, solid and potentially useful to us, and what is just smoke and mirrors.

In a culture that has fallen a little too much in love with the voices of experts it’s all too easy to submit ourselves to their confident pronouncements and stop reflecting upon and weighing what we are hearing. The premise of this book is that we may not know that much about the human mind yet, but since we all have one we should probably do our best to use it. Berne’s most famous patent clerk urged us to remember that ‘the important thing is not to stop questioning’, but that can be especially hard when we are being told what we badly want to hear. Nevertheless, it’s time to be firm with ourselves, take back some responsibility for our own lives, and wean ourselves off the easy panaceas the world of Psychobabble is all too eager to flog us.

I hope this doesn’t read like one of those smart-alecky ‘Everything You Think You Know is Wrong’ books. I am not trying to be argumentative for the sake of it. I am not even claiming that the views and positions expressed in these pages are necessarily right. My hope is merely that they stimulate your own thinking, and give you the confidence to start drawing your own conclusions. If you disagree with me, that’s completely fine. As Caroline Aherne’s great comic creation Mrs Merton used to enjoin her audience: ‘Let’s have a heated debate ...’

In medicine, doctors sometimes talk about iatrogenesis, which is a fancy way of describing those unfortunate occasions when the interventions designed to cure us have the unfortunate side-effect of making us worse. I have a strong suspicion that this may be exactly what is happening in the case of popular psychology. Whether by the end of this book you agree with me, I hope that what follows will provide some entertaining food for thought, ease the heavy burden of unrealistic expectation, and discourage any of us from ever taking the received wisdom of our times at face value.

A BRIEF WORD ON REFERENCING

Whenever a study, quotation or reference of any kind is mentioned in the text, look up the original page number in the References at the end of the book and you will find the relevant lines from the main text reprinted in italics with a brief reference underneath e.g. Rogers (1990). This will then give you sufficient information to find the full reference in the Bibliography, on p.237 or, where a web reference is cited, online.

Referencing has been done this way in order to avoid cluttering the main text with numbering, while still allowing the reader to locate the relevant sources more easily than if they had just been listed at the end of each chapter. Have a quick look at the reference section and you should find the system fairly self-explanatory.