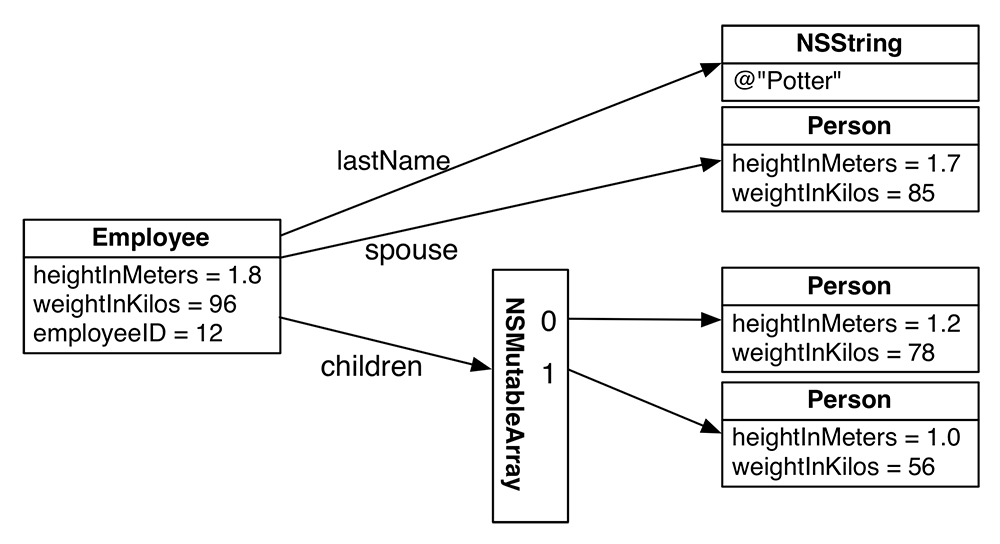

Thus far, the instance variables declared in your classes have been simple C types like int or float. It’s far more common for instance variables to be pointers to other objects. An object instance variable points to another object and describes a relationship between the two objects. Usually, object instance variables fall into one of three categories:

Object-type attributes: a pointer to a simple, value-like object like an NSString or an NSNumber. For example, an employee’s last name would be stored in an NSString. Thus, an instance of Employee would have an instance variable that would be a pointer to an instance of NSString.

To-one relationships: a pointer to a single complex object. For example, an employee might have a spouse. Thus, an instance of Employee would have an instance variable that would be a pointer to an instance of Person.

To-many relationships: a pointer to an instance of a collection class, such as an NSMutableArray. (We’ll see other examples of collections in Chapter 21.) For example, an employee might have children. In this case, the instance of Employee would have an instance variable that would be a pointer to an instance of NSMutableArray. The NSMutableArray would hold a list of pointers to one or more Person objects.

(Notice that, in the above list, I refer to “an NSString.” NSString is the class, but “an NSString” is shorthand for an NSString instance. This usage is a little confusing but very common, so it’s good to get comfortable with it.)

Notice that, as in other diagrams, pointers are represented by arrows. In addition, those pointers are named. So an Employee would have three new instance variables: lastName, spouse, and children. The declaration of Employee’s instance variables would look like this:

@interface Employee : Person

{

int employeeID;

NSString *lastName;

Person *spouse;

NSMutableArray *children;

}

With the exception of employeeID, these variables are all pointers. Object instance variables are always pointers. For example, the variable spouse is a pointer to another object that lives on the heap. The pointer spouse is inside the Employee object, but the Person object it points to is not. Objects don’t live inside other objects. The employee object contains its employee ID (the variable and the value itself), but it only knows where its spouse lives in memory.

There are two important side-effects to objects pointing to rather than containing other objects:

One object can take on several roles. For example, it is likely that the employee’s spouse is also listed as the emergency contact for the children:

You end up with a lot of distinct objects using up your program’s memory. You need the objects being used to stay around, but you want the unnecessary ones to be deallocated (have their memory returned to the heap) so that their memory can be reused. Reusing memory keeps your program’s memory footprint as small as possible, which will make your entire computer feel more responsive. On a mobile device (like an iPhone), the operating system will kill your program if its memory footprint gets too big.

To manage these issues, we have the idea of object ownership. When an object has an object instance variable, the object with the pointer is said to own the object that is being pointed to.

From the other end of things, an object knows how many owners it currently has. For instance, in the diagram above, the instance of Person has three owners: the Employee object and the two Child objects. When an object has zero owners, it figures no one needs it around anymore and deallocates itself.

The owner count of each object is handled by Automatic Reference Counting. ARC is a recent development in Objective-C. Before Xcode 4.2, we managed ownership manually and spent a lot of time and effort doing so. (There’s more about manual reference counting and how it worked in the final section of Chapter 20. All the code in this book, however, assumes that you are using ARC.)

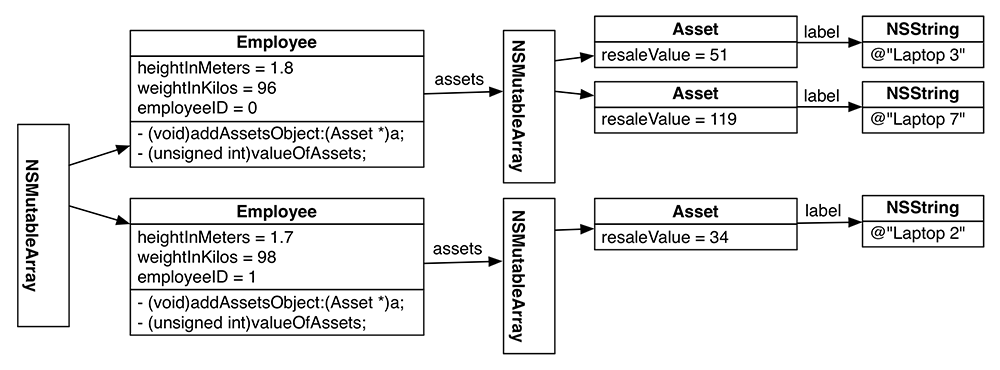

Let’s expand the BMITime project to see how ownership works in practice. It is not uncommon for a company to keep track of what assets have been issued to which employee. We are going to create an Asset class, and each Employee will have an array containing his or her assets.

This is often called a “parent-child” relationship: The parent (an instance of Employee) has a collection of children (an NSMutableArray of Asset objects).

Create a new file: an Objective-C subclass of NSObject. Name it Asset. Open Asset.h and declare two instance variables and two properties:

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

@interface Asset : NSObject

{

NSString *label;

unsigned int resaleValue;

}

@property (strong) NSString *label;

@property unsigned int resaleValue;

@end

Notice the strong modifier on the @property declaration for label. That says, “This is a pointer to an object upon which I claim ownership.” (We’ll talk about other options for this property attribute in Chapter 20.)

Remember that when an object doesn’t have any owners, it is deallocated. When an object is being deallocated, it is sent the message dealloc. (Every object inherits the dealloc method from NSObject.) You are going to override dealloc so that you can see when instances of Asset are being deallocated.

To make it clear which particular instance of Asset is being deallocated, you’ll also implement another NSObject method, description. This method returns a string that is a useful description of an instance of the class. For Asset, you’re going to have description return a string that includes the instance’s label and resaleValue.

Open Asset.m. Synthesize the accessors for your instance variables and then override description and dealloc.

#import "Asset.h"

@implementation Asset

@synthesize label, resaleValue;

- (NSString *)description

{

return [NSString stringWithFormat:@"<%@: $%d >",

[self label], [self resaleValue]];

}

- (void)dealloc

{

NSLog(@"deallocating %@", self);

}

@end

Notice the %@ token in the format strings in the code above. This token is replaced with the result of sending the description message to the corresponding variable (which must be a pointer to an object so that it can receive this message).

Try building what you have so far to see if you made any errors typing it in. You can build your program without running it by using the keyboard shortcut Command-B. This is useful for testing your code without taking the time to run the program or when you know the program isn’t ready to run yet. Plus, it’s always a good idea to build after making changes so that if you’ve introduced a syntax error, you can find and fix it right away. If you wait, you won’t be as sure what changes are responsible for your “new” bug.

Now you are going to add a to-many relationship to the Employee class. Recall that a to-many relationship includes a collection object (like an array) and the objects contained in the collection. There are two other important things to know about collections and ownership:

When an object is added to the collection, the collection establishes a pointer to the object, and the object gains an owner.

When an object is removed from a collection, the collection gets rid of its pointer to the object, and the object loses an owner.

To set up the to-many relationship in Employee, you’ll need a new instance variable to hold a pointer to the mutable array of assets. You’ll also need a couple of methods. Open Employee.h and add them:

#import "Person.h"

@class Asset;

@interface Employee : Person

{

int employeeID;

NSMutableArray *assets;

}

@property int employeeID;

- (void)addAssetsObject:(Asset *)a;

- (unsigned int)valueOfAssets;

@end

Notice the line that says @class Asset;. As the compiler is reading this file, it will come across the class name Asset. If it doesn’t know about the class, it will throw an error. The @class Asset; line tells the compiler “There is a class called Asset. Don’t panic when you see it in this file. That’s all you need to know for now.”

Using @class instead of #import gives the compiler less information, but makes the processing of this particular file faster. You can use @class with Employee.h and other header files because the compiler doesn’t need to know a lot to process a file of declarations.

Now turn your attention to Employee.m. With a to-many relationship, you need to create the collection object (an array, in our case) before you put anything in it. You can do this when the original object (an employee) is first created, or you can be lazy and wait until the collection is needed. Let’s be lazy.

#import "Employee.h"

#import "Asset.h"

@implementation Employee

@synthesize employeeID;

- (void)addAssetsObject:(Asset *)a

{

// Is assets nil?

if (!assets) {

// Create the array

assets = [[NSMutableArray alloc] init];

}

[assets addObject:a];

}

- (unsigned int)valueOfAssets

{

// Sum up the resale value of the assets

unsigned int sum = 0;

for (Asset *a in assets) {

sum += [a resaleValue];

}

return sum;

}

- (float)bodyMassIndex

{

float normalBMI = [super bodyMassIndex];

return normalBMI * 0.9;

}

- (NSString *)description

{

return [NSString stringWithFormat:@"<Employee %d: $%d in assets>",

[self employeeID], [self valueOfAssets]];

}

- (void)dealloc

{

NSLog(@"deallocating %@", self);

}

@end

To process the Employee.m file, the compiler needs to know a lot about the Asset class. Thus, you imported Asset.h instead of using @class.

Also notice that you overrode description and dealloc to track the deallocation of Employee instances.

Build the project to see if you’ve made any mistakes.

Now you need to create some assets and assign them to employees. Edit main.m:

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

#import "Employee.h"

#import "Asset.h"

int main(int argc, const char * argv[])

{

@autoreleasepool {

// Create an array of Employee objects

NSMutableArray *employees = [[NSMutableArray alloc] init];

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

// Create an instance of Employee

Employee *person = [[Employee alloc] init];

// Give the instance variables interesting values

[person setWeightInKilos:90 + i];

[person setHeightInMeters:1.8 - i/10.0];

[person setEmployeeID:i];

// Put the employee in the employees array

[employees addObject:person];

}

// Create 10 assets

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

// Create an asset

Asset *asset = [[Asset alloc] init];

// Give it an interesting label

NSString *currentLabel = [NSString stringWithFormat:@"Laptop %d", i];

[asset setLabel:currentLabel];

[asset setResaleValue:i * 17];

// Get a random number between 0 and 9 inclusive

NSUInteger randomIndex = random() % [employees count];

// Find that employee

Employee *randomEmployee = [employees objectAtIndex:randomIndex];

// Assign the asset to the employee

[randomEmployee addAssetsObject:asset];

}

NSLog(@"Employees: %@", employees);

NSLog(@"Giving up ownership of one employee");

[employees removeObjectAtIndex:5];

NSLog(@"Giving up ownership of array");

employees = nil;

}

return 0;

}Build and run the program. You should see something like this:

Employees: ( "<Employee 0: $0 in assets>", "<Employee 1: $153 in assets>", "<Employee 2: $119 in assets>", "<Employee 3: $68 in assets>", "<Employee 4: $0 in assets>", "<Employee 5: $136 in assets>", "<Employee 6: $119 in assets>", "<Employee 7: $34 in assets>", "<Employee 8: $0 in assets>", "<Employee 9: $136 in assets>" ) Giving up ownership of one employee deallocating <Employee 5: $136 in assets> deallocating <Laptop 3: $51 > deallocating <Laptop 5: $85 > Giving up ownership of array deallocating <Employee 0: $0 in assets> deallocating <Employee 1: $153 in assets> deallocating <Laptop 9: $153 > … deallocating <Employee 9: $136 in assets> deallocing <Laptop 8: $136 >

When employee #5 is removed from the array, it is deallocated because it has no owner. Then its assets are deallocated because they have no owner. (And you’ll have to trust me on this: the labels (instances of NSString) of the deallocated assets are also deallocated once they have no owner.)

When employees is set to nil, the array no longer has an owner. So it is deallocated, which sets up an even larger chain reaction of memory clean-up and deallocation when, suddenly, none of the employees has an owner.

Tidy, right? As the objects become unnecessary, they are being deallocated. This is good. When unnecessary objects don’t get deallocated, you are said to have a memory leak. Typically a memory leak causes more and more objects to linger unnecessarily over time. The memory footprint of your application just gets bigger and bigger. On iOS, the operating system will eventually kill your application. On Mac OS X, the performance of the entire system will suffer as the machine spends more and more time swapping data out of memory and onto disk.