After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Inventories are asset items that a company holds for sale in the ordinary course of business, or goods that it will use or consume in the production of goods to be sold. The description and measurement of inventory require careful attention. The investment in inventories is frequently the largest current asset of merchandising (retail) and manufacturing businesses.

A merchandising concern, such as Wal-Mart, usually purchases its merchandise in a form ready for sale. It reports the cost assigned to unsold units left on hand as merchandise inventory. Only one inventory account, Merchandise Inventory, appears in the financial statements.

Manufacturing concerns, on the other hand, produce goods to sell to merchandising firms. Many of the largest U.S. businesses are manufacturers, such as Boeing, IBM, Exxon Mobil, Procter & Gamble, Ford, and Motorola. Although the products they produce may differ, manufacturers normally have three inventory accounts—Raw Materials, Work in Process, and Finished Goods.

A company reports the cost assigned to goods and materials on hand but not yet placed into production as raw materials inventory. Raw materials include the wood to make a baseball bat or the steel to make a car. These materials can be traced directly to the end product.

At any point in a continuous production process some units are only partially processed. The cost of the raw material for these unfinished units, plus the direct labor cost applied specifically to this material and a ratable share of manufacturing overhead costs, constitute the work in process inventory.

Companies report the costs identified with the completed but unsold units on hand at the end of the fiscal period as finished goods inventory. Illustration 8-1 contrasts the financial statement presentation of inventories of Wal-Mart (a merchandising company) with those of Caterpillar (a manufacturing company.) The remainder of the balance sheet is essentially similar for the two types of companies.

Figure 8-1. Comparison of Presentation of Current Assets for Merchandising and Manufacturing Companies

As indicated above, a manufacturing company, like Caterpillar, also might include a Manufacturing or Factory Supplies Inventory account. In it, Caterpillar would include such items as machine oils, nails, cleaning material, and the like—supplies that are used in production but are not the primary materials being processed.

Illustration 8-2 shows the differences in the flow of costs through a merchandising company and a manufacturing company.

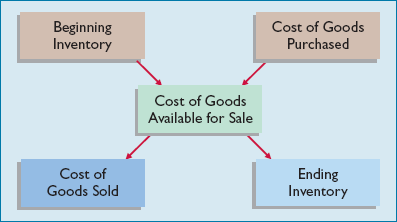

Companies that sell or produce goods report inventory and cost of goods sold at the end of each accounting period. To determine these amounts, they add beginning inventory to purchases for the period to arrive at cost of goods available for sale. Cost of goods available for sale is then assigned to ending inventory and cost of goods sold based on the amount of goods in ending inventory and the goods sold. Illustration 8-3 shows the flow of inventoriable costs.

Companies use one of two types of systems for maintaining accurate inventory records for these costs—the perpetual system or the periodic system.

A perpetual inventory system continuously tracks changes in the Inventory account. That is, a company records all purchases and sales (issues) of goods directly in the Inventory account as they occur. The accounting features of a perpetual inventory system are as follows.

Purchases of merchandise for resale or raw materials for production are debited to Inventory rather than to Purchases.

Freight-in is debited to Inventory, not Purchases. Purchase returns and allowances and purchase discounts are credited to Inventory rather than to separate accounts.

Cost of goods sold is recorded at the time of each sale by debiting Cost of Goods Sold and crediting Inventory.

A subsidiary ledger of individual inventory records is maintained as a control measure. The subsidiary records show the quantity and cost of each type of inventory on hand.

The perpetual inventory system provides a continuous record of the balances in both the Inventory account and the Cost of Goods Sold account.

Under a periodic inventory system, a company determines the quantity of inventory on hand only periodically, as the name implies. It records all acquisitions of inventory during the accounting period by debiting the Purchases account. A company then adds the total in the Purchases account at the end of the accounting period to the cost of the inventory on hand at the beginning of the period. This sum determines the total cost of the goods available for sale during the period.

To compute the cost of goods sold, the company then subtracts the ending inventory from the cost of goods available for sale. Note that under a periodic inventory system, the cost of goods sold is a residual amount that depends on a physical count of ending inventory. This process is referred to as "taking a physical inventory." Companies that use the periodic system take a physical inventory at least once a year.

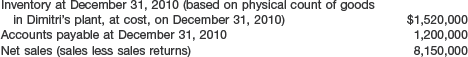

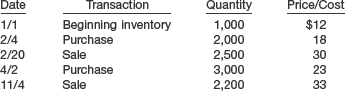

To illustrate the difference between a perpetual and a periodic system, assume that Fesmire Company had the following transactions during the current year.

Fesmire records these transactions during the current year as shown in Illustration 8-4.

When a company uses a perpetual inventory system and a difference exists between the perpetual inventory balance and the physical inventory count, it needs a separate entry to adjust the perpetual inventory account. To illustrate, assume that at the end of the reporting period, the perpetual inventory account reported an inventory balance of $4,000. However, a physical count indicates inventory of $3,800 is actually on hand. The entry to record the necessary write-down is as follows.

Perpetual inventory overages and shortages generally represent a misstatement of cost of goods sold. The difference results from normal and expected shrinkage, breakage, shoplifting, incorrect recordkeeping, and the like. Inventory Over and Short therefore adjusts Cost of Goods Sold. In practice, companies sometimes report Inventory Over and Short in the "Other revenues and gains" or "Other expenses and losses" section of the income statement.

Note that a company using the periodic inventory system does not report the account Inventory Over and Short. The reason: The periodic method does not have accounting records against which to compare the physical count. As a result, a company buries inventory overages and shortages in cost of goods sold.

For various reasons, management is vitally interested in inventory planning and control. Whether a company manufactures or merchandises goods, it needs an accurate accounting system with up-to-date records. It may lose sales and customers if it does not stock products in the desired style, quality, and quantity. Further, companies must monitor inventory levels carefully to limit the financing costs of carrying large amounts of inventory.

In a perfect world, companies would like a continuous record of both their inventory levels and their cost of goods sold. The popularity and affordability of computerized accounting software makes the perpetual system cost-effective for many kinds of businesses. Companies like Target, Best Buy, and Sears Holdings now incorporate the recording of sales with optical scanners at the cash register into perpetual inventory systems.

However, many companies cannot afford a complete perpetual system. But, most of these companies need current information regarding their inventory levels, to protect against stockouts or overpurchasing and to aid in preparation of monthly or quarterly financial data. As a result, these companies use a modified perpetual inventory system. This system provides detailed inventory records of increases and decreases in quantities only—not dollar amounts. It is merely a memorandum device outside the double-entry system, which helps in determining the level of inventory at any point in time.

Whether a company maintains a complete perpetual inventory in quantities and dollars or a modified perpetual inventory system, it probably takes a physical inventory once a year. No matter what type of inventory records companies use, they all face the danger of loss and error. Waste, breakage, theft, improper entry, failure to prepare or record requisitions, and other similar possibilities may cause the inventory records to differ from the actual inventory on hand. Thus, all companies need periodic verification of the inventory records by actual count, weight, or measurement, with the counts compared with the detailed inventory records. As indicated earlier, a company corrects the records to agree with the quantities actually on hand.

Insofar as possible, companies should take the physical inventory near the end of their fiscal year, to properly report inventory quantities in their annual accounting reports. Because this is not always possible, however, physical inventories taken within two or three months of the year's end are satisfactory, if a company maintains detailed inventory records with a fair degree of accuracy.[100]

With the introduction and use of "just-in-time" (JIT) inventory order systems and better supplier relationships, many companies have leaner inventory levels.

Wal-Mart provides a classic example of the use of tight inventory controls. Department managers use a scanner that when placed over the bar code corresponding to a particular item, will tell them how many of the items the store sold yesterday, last week, and over the same period last year. It will tell them how many of those items are in stock, how many are on the way, and how many the neighboring Wal-Marts are carrying (in case one store runs out). Such practices have helped Wal-Mart become one of the top-ranked companies on the Fortune 500 in terms of sales.

Goods sold (or used) during an accounting period seldom correspond exactly to the goods bought (or produced) during that period. As a result, inventories either increase or decrease during the period. Companies must then allocate the cost of all the goods available for sale (or use) between the goods that were sold or used and those that are still on hand. The cost of goods available for sale or use is the sum of (1) the cost of the goods on hand at the beginning of the period, and (2) the cost of the goods acquired or produced during the period. The cost of goods sold is the difference between (1) the cost of goods available for sale during the period, and (2) the cost of goods on hand at the end of the period. Illustration 8-5 shows these calculations.

Valuing inventories can be complex. It requires determining the following.

We explore these basic issues in the next three sections.

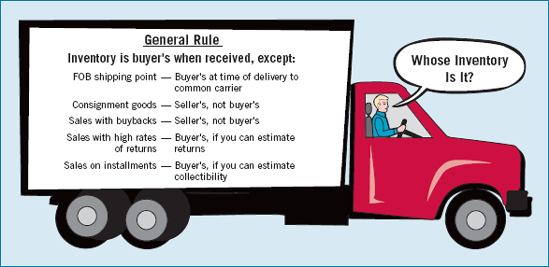

Technically, a company should record purchases when it obtains legal title to the goods. In practice, however, a company records acquisitions when it receives the goods. Why? Because it is difficult to determine the exact time of legal passage of title for every purchase. In addition, no material error likely results from such a practice if consistently applied. Illustration 8-6 (page 387) indicates the general guidelines companies use in evaluating whether the seller or buyer reports an item as inventory. Exceptions to the general guidelines can arise for goods in transit and consigned goods.

Sometimes purchased merchandise remains in transit—not yet received—at the end of a fiscal period. The accounting for these shipped goods depends on who owns them. For example, a company like Walgreens determines ownership by applying the "passage of title" rule. If a supplier ships goods to Walgreens f.o.b. shipping point, title passes to Walgreens when the supplier delivers the goods to the common carrier, who acts as an agent for Walgreens. (The abbreviation f.o.b. stands for free on board.) If the supplier ships the goods f.o.b. destination, title passes to Walgreens only when it receives the goods from the common carrier. "Shipping point" and "destination" are often designated by a particular location, for example, f.o.b. Denver.

When Walgreens obtains legal title to goods, it must record them as purchases in that fiscal period, assuming a periodic inventory system. Thus, goods shipped to Walgreens f.o.b. shipping point, but in transit at the end of the period, belong to Walgreens. It should show the purchase in its records, because legal title to these goods passed to Walgreens upon shipment of the goods. To disregard such purchases results in understating inventories and accounts payable in the balance sheet, and understating purchases and ending inventories in the income statement.

Companies market certain products through a consignment shipment. Under this arrangement, a company like Williams' Art Gallery (the consignor) ships various art merchandise to Sotheby's Holdings (the consignee), who acts as Williams' agent in selling the consigned goods. Sotheby's agrees to accept the goods without any liability, except to exercise due care and reasonable protection from loss or damage, until it sells the goods to a third party. When Sotheby's sells the goods, it remits the revenue, less a selling commission and expenses incurred in accomplishing the sale, to Williams.

Goods out on consignment remain the property of the consignor (Williams in the example above). Williams thus includes the goods in its inventory at purchase price or production cost. Occasionally, and only for a significant amount, the consignor shows the inventory out on consignment as a separate item. Sometimes a consignor reports the inventory on consignment in the notes to the financial statements. For example, Eagle Clothes, Inc. reported the following related to consigned goods: "Inventories consist of finished goods shipped on consignment to customers of the Company's subsidiary April-Marcus, Inc."

The consignee makes no entry to the inventory account for goods received. Remember, these goods remain the property of the consignor until sold. In fact, the consignee should be extremely careful not to include any of the goods consigned as a part of inventory.

As we indicated earlier, transfer of legal title is the general guideline used to determine whether a company should include an item in inventory. Unfortunately, transfer of legal title and the underlying substance of the transaction often do not match. For example, legal title may have passed to the purchaser, but the seller of the goods retains the risks of ownership. Conversely, transfer of legal title may not occur, but the economic substance of the transaction is such that the seller no longer retains the risks of ownership.

Three special sales situations are illustrated here to indicate the types of problems companies encounter in practice. These are:

Sometimes an enterprise finances its inventory without reporting either the liability or the inventory on its balance sheet. This approach, often referred to as a product financing arrangement, usually involves a "sale" with either an implicit or explicit "buyback" agreement.

To illustrate, Hill Enterprises transfers ("sells") inventory to Chase, Inc. and simultaneously agrees to repurchase this merchandise at a specified price over a specified period of time. Chase then uses the inventory as collateral and borrows against it. Chase uses the loan proceeds to pay Hill, which repurchases the inventory in the future. Chase employs the proceeds from repayment to meet its loan obligation.

The essence of this transaction is that Hill Enterprises is financing its inventory—and retaining risk of ownership—even though it transferred to Chase technical legal title to the merchandise. By structuring a transaction in this manner, Hill avoids personal property taxes in certain states. Other advantages of this transaction for Hill are the removal of the current liability from its balance sheet and the ability to manipulate income. For Chase, the purchase of the goods may solve a LIFO liquidation problem (discussed later), or Chase may enter into a similar reciprocal agreement at a later date.

These arrangements are often described in practice as "parking transactions." In this situation, Hill simply parks the inventory on Chase's balance sheet for a short period of time. When a repurchase agreement exists at a set price and this price covers all costs of the inventory plus related holding costs, Hill should report the inventory and related liability on its books. [1]

In industries such as publishing, music, toys, and sporting goods, formal or informal agreements often exist that permit purchasers to return inventory for a full or partial refund.

To illustrate, Quality Publishing Company sells textbooks to Campus Bookstores with an agreement that Campus may return for full credit any books not sold. Historically, Campus Bookstores returned approximately 25 percent of the textbooks from Quality Publishing. How should Quality Publishing report its sales transactions?

One alternative is to record the sale at the full amount and establish an estimated sales returns and allowances account. A second possibility is to not record any sale until circumstances indicate the amount of inventory the buyer will return. The key question is: Under what circumstances should Quality Publishing consider the inventory sold? The answer is that when Quality Publishing can reasonably estimate the amount of returns, it should consider the goods sold. Conversely, if returns are unpredictable, Quality Publishing should not consider the goods sold and it should not remove the goods from its inventory. [2]

"Goods sold on installment" describes any type of sale in which the sale agreement requires payment in periodic installments over an extended period of time. Because the risk of loss from uncollectibles is higher in installment-sale situations than in other sales transactions, the seller sometimes withholds legal title to the merchandise until the buyer has made all the payments.

The question is whether the seller should consider the inventory sold, even though legal title has not passed. The answer is that the seller should exclude the goods from its inventory if it can reasonably estimate the percentage of bad debts.

In one of the more elaborate accounting frauds, employees at Kurzweil Applied Intelligence Inc. booked millions of dollars in phony inventory sales during a two-year period that straddled two audits and an initial public stock offering. They dummied up phony shipping documents and logbooks to support bogus sales transactions. Then they shipped high-tech equipment, not to customers, but to a public warehouse for "temporary" storage, where some of it sat for 17 months. (Kurzweil still had ownership.)

To foil auditors' attempts to verify the existence of the inventory, Kurzweil employees moved the goods from warehouse to warehouse. To cover the fraudulently recorded sales transactions as auditors closed in, the employees brought back the still-hidden goods, under the pretense that the goods were returned by customers. When auditors uncovered the fraud, the bottom dropped out of Kurzweil's stock.

Similar inventory shenanigans occurred at Delphi, which used side-deals with third parties to get inventory off its books and to record sales. The overstatement in income eventually led to a bankruptcy filing for Delphi.

Source: Adapted from "Anatomy of a Fraud," Business Week (September 16, 1996), pp. 90–94; and J. McCracken, "Delphi Executives Named in Suit over Inventory Practices," Wall Street Journal (May 5, 2005), p. A3.

Items incorrectly included or excluded in determining cost of goods sold through inventory misstatements will result in errors in the financial statements. Let's look at two cases, assuming a periodic inventory system.

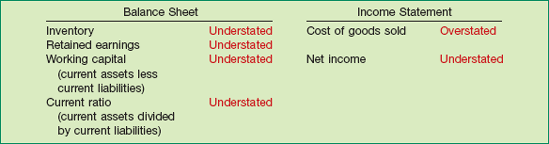

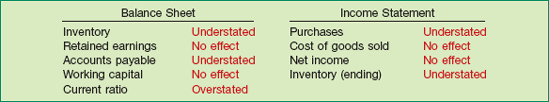

What would happen if IBM correctly records its beginning inventory and purchases, but fails to include some items in ending inventory? In this situation, we would have the following effects on the financial statements at the end of the period.

If ending inventory is understated, working capital and the current ratio are understated. If cost of goods sold is overstated, then net income is understated.

To illustrate the effect on net income over a two-year period (2009–2010), assume that Jay Weiseman Corp. understates its ending inventory by $10,000 in 2009; all other items are correctly stated. The effect of this error is to decrease net income in 2009 and to increase net income in 2010. The error is counterbalanced (offset) in 2010 because beginning inventory is understated and net income is overstated. As Illustration 8-8 shows, the income statement misstates the net income figures for both 2009 and 2010, although the total for the two years is correct.

If Weiseman overstates ending inventory in 2009, the reverse effect occurs: Inventory, working capital, current ratio, and net income are overstated and cost of goods sold is understated. The effect of the error on net income will be counterbalanced in 2010, but the income statement misstates both years' net income figures.

Suppose that Bishop Company does not record as a purchase certain goods that it owns and does not count them in ending inventory. The effect on the financial statements (assuming this is a purchase on account) is as follows.

Omission of goods from purchases and inventory results in an understatement of inventory and accounts payable in the balance sheet; it also results in an understatement of purchases and ending inventory in the income statement. However, the omission of such goods does not affect net income for the period. Why not? Because Bishop understates both purchases and ending inventory by the same amount—the error is thereby offset in cost of goods sold. Total working capital is unchanged, but the current ratio is overstated because of the omission of equal amounts from inventory and accounts payable.

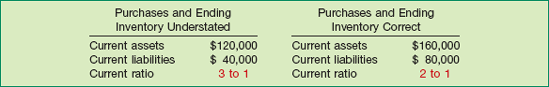

To illustrate the effect on the current ratio, assume that Bishop understated accounts payable and ending inventory by $40,000. Illustration 8-10 shows the understated and correct data.

The understated data indicate a current ratio of 3 to 1, whereas the correct ratio is 2 to 1. Thus, understatement of accounts payable and ending inventory can lead to a "window dressing" of the current ratio. That is, Bishop can make the current ratio appear better than it is.

If Bishop overstates both purchases (on account) and ending inventory, then the effects on the balance sheet are exactly the reverse: The financial statements overstate inventory and accounts payable, and understate the current ratio. The overstatement does not affect cost of goods sold and net income because the errors offset one another. Similarly, working capital is not affected.

We cannot overemphasize the importance of proper inventory measurement in presenting accurate financial statements. For example, Leslie Fay, a women's apparel maker, had accounting irregularities that wiped out one year's net income and caused a restatement of the prior year's earnings. One reason: It inflated inventory and deflated cost of goods sold. Anixter Bros. Inc. had to restate its income by $1.7 million because an accountant in the antenna manufacturing division overstated the ending inventory, thereby reducing its cost of sales. Similarly, AM International allegedly recorded as sold products that were only being rented. As a result, inaccurate inventory and sales figures inappropriately added $7.9 million to pretax income.

One of the most important problems in dealing with inventories concerns the dollar amount at which to carry the inventory in the accounts. Companies generally account for the acquisition of inventories, like other assets, on a cost basis.

Product costs are those costs that "attach" to the inventory. As a result, a company records product costs in the inventory account. These costs are directly connected with bringing the goods to the buyer's place of business and converting such goods to a salable condition. Such charges include freight charges on goods purchased, other direct costs of acquisition, and labor and other production costs incurred in processing the goods up to the time of sale.

It seems proper also to allocate to inventories a share of any buying costs or expenses of a purchasing department, storage costs, and other costs incurred in storing or handling the goods before their sale. However, because of the practical difficulties involved in allocating such costs and expenses, companies usually exclude these items in valuing inventories.

A manufacturing company's costs include direct materials, direct labor, and manufacturing overhead costs. Manufacturing overhead costs include indirect materials, indirect labor, and various costs, such as depreciation, taxes, insurance, and heat and electricity.

Period costs are those costs that are indirectly related to the acquisition or production of goods. Period costs such as selling expenses and, under ordinary circumstances, general and administrative expenses are therefore not included as part as part of inventory cost.

Yet, conceptually, these expenses are as much a cost of the product as the initial purchase price and related freight charges attached to the product. Why then do companies exclude these costs from inventoriable items? Because companies generally consider selling expenses as more directly related to the cost of goods sold than to the unsold inventory. In addition, period costs, especially administrative expenses, are so unrelated or indirectly related to the immediate production process that any allocation is purely arbitrary.[101]

Interest is another period cost. Companies usually expense interest costs associated with getting inventories ready for sale. Supporters of this approach argue that interest costs are really a cost of financing. Others contend that interest costs incurred to finance activities associated with readying inventories for sale are as much a cost of the asset as materials, labor, and overhead. Therefore, they reason, companies should capitalize interest costs.

The FASB ruled that companies should capitalize interest costs related to assets constructed for internal use or assets produced as discrete projects (such as ships or real estate projects) for sale or lease [4].[102] The FASB emphasized that these discrete projects should take considerable time, entail substantial expenditures, and be likely to involve significant amounts of interest cost. A company should not capitalize interest costs for inventories that it routinely manufactures or otherwise produces in large quantities on a repetitive basis. In this case, the informational benefit does not justify the cost.

The use of a Purchase Discounts account in a periodic inventory system indicates that the company is reporting its purchases and accounts payable at the gross amount. If a company uses this gross method, it reports purchase discounts as a deduction from purchases on the income statement.

Another approach is to record the purchases and accounts payable at an amount net of the cash discounts. In this approach, the company records failure to take a purchase discount within the discount period in a Purchase Discounts Lost account. If a company uses this net method, it considers purchase discounts lost as a financial expense and reports it in the "Other expenses and losses" section of the income statement. This treatment is considered better for two reasons: (1) It provides a correct reporting of the cost of the asset and related liability. (2) It can measure management inefficiency by holding management responsible for discounts not taken.

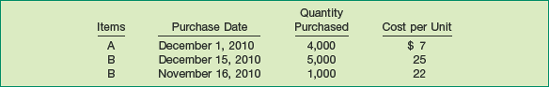

To illustrate the difference between the gross and net methods, assume the following transactions.

Many believe that the somewhat more complicated net method is not justified by the resulting benefits. This could account for the widespread use of the less logical but simpler gross method. In addition, some contend that management is reluctant to report in the financial statements the amount of purchase discounts lost.

Does it really matter where a company reports certain costs in its income statement, as long as it includes them all as expenses in computing income?

For e-tailers, such as Amazon.com or Drugstore.com, where they report certain selling costs does appear to be important. Contrary to well-established retailer practices, these companies insist on reporting some selling costs—fulfillment costs related to inventory shipping and warehousing—as part of administrative expenses, instead of as cost of goods sold. This practice is allowable within GAAP, if applied consistently and adequately disclosed. Although the practice doesn't affect the bottom line, it does make the e-tailers' gross margins look better. For example, at one time Amazon.com reported $265 million of these costs in one quarter. Some experts thought Amazon.com should include those charges in costs of goods sold, which would substantially lower its gross profit, as shown below.

Similarly, if Drugstore.com and eToys.com made similar adjustments, their gross margins would go from positive to negative.

Thus, if you want to be able to compare the operating results of e-tailers to other traditional retailers, it might be a good idea to have a good accounting map in order to navigate their income statements and how they report certain selling costs.

Source: Adapted from P. Elstrom, "The End of Fuzzy Math?" Business Week, e.Biz—Net Worth (December 11, 2000). According to GAAP [5], companies must disclose the accounting policy for classifying these selling costs in income.

During any given fiscal period, companies typically purchase merchandise at several different prices. If a company prices inventories at cost and it made numerous purchases at different unit costs, which cost price should it use? Conceptually, a specific identification of the given items sold and unsold seems optimal. But this measure often proves both expensive and impossible to achieve. Consequently, companies use one of several systematic inventory cost flow assumptions.

Indeed, the actual physical flow of goods and the cost flow assumption often greatly differ. There is no requirement that the cost flow assumption adopted be consistent with the physical movement of goods. A company's major objective in selecting a method should be to choose the one that, under the circumstances, most clearly reflects periodic income. [6]

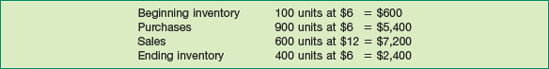

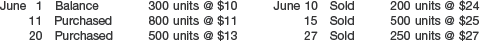

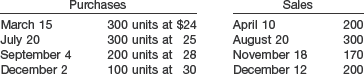

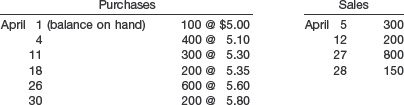

To illustrate, assume that Call-Mart Inc. had the following transactions in its first month of operations.

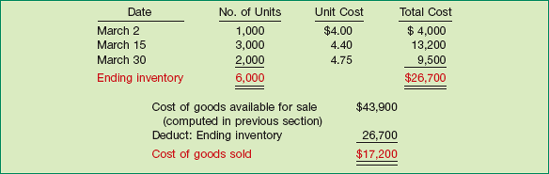

From this information, Call-Mart computes the ending inventory of 6,000 units and the cost of goods available for sale (beginning inventory + purchases) of $43,900 [(2,000 @ $4.00) + (6,000 @ $4.40) + (2,000 @ $4.75)]. The question is, which price or prices should it assign to the 6,000 units of ending inventory? The answer depends on which cost flow assumption it uses.

Specific identification calls for identifying each item sold and each item in inventory. A company includes in cost of goods sold the costs of the specific items sold. It includes in inventory the costs of the specific items on hand. This method may be used only in instances where it is practical to separate physically the different purchases made. As a result, most companies only use this method when handling a relatively small number of costly, easily distinguishable items. In the retail trade this includes some types of jewelry, fur coats, automobiles, and some furniture. In manufacturing it includes special orders and many products manufactured under a job cost system.

To illustrate, assume that Call-Mart Inc.'s 6,000 units of inventory consists of 1,000 units from the March 2 purchase, 3,000 from the March 15 purchase, and 2,000 from the March 30 purchase. Illustration 8-12 shows how Call-Mart computes the ending inventory and cost of goods sold.

This method appears ideal. Specific identification matches actual costs against actual revenue. Thus, a company reports ending inventory at actual cost. In other words, under specific identification the cost flow matches the physical flow of the goods. On closer observation, however, this method has certain deficiencies.

Some argue that specific identification allows a company to manipulate net income. For example, assume that a wholesaler purchases identical plywood early in the year at three different prices. When it sells the plywood, the wholesaler can select either the lowest or the highest price to charge to expense. It simply selects the plywood from a specific lot for delivery to the customer. A business manager, therefore, can manipulate net income by delivering to the customer the higher- or lower-priced item, depending on whether the company seeks lower or higher reported earnings for the period.

Another problem relates to the arbitrary allocation of costs that sometimes occurs with specific inventory items. For example, a company often faces difficulty in relating shipping charges, storage costs, and discounts directly to a given inventory item. This results in allocating these costs somewhat arbitrarily, leading to a "breakdown" in the precision of the specific identification method.[103]

As the name implies, the average cost method prices items in the inventory on the basis of the average cost of all similar goods available during the period. To illustrate use of the periodic inventory method (amount of inventory computed at the end of the period), Call-Mart computes the ending inventory and cost of goods sold using a weighted-average method as follows.

In computing the average cost per unit, Call-Mart includes the beginning inventory, if any, both in the total units available and in the total cost of goods available.

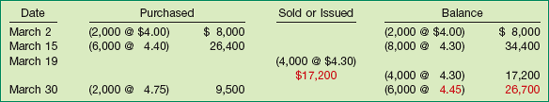

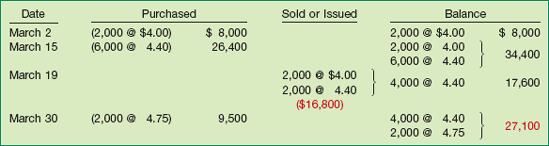

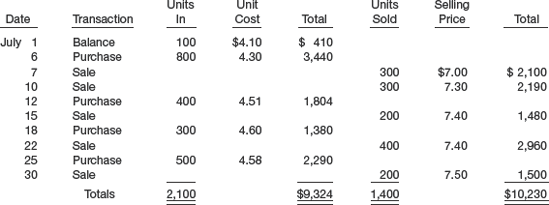

Companies use the moving-average method with perpetual inventory records. Illustration 8-14 shows the application of the average cost method for perpetual records.

In this method, Call-Mart computes a new average unit cost each time it makes a purchase. For example, on March 15, after purchasing 6,000 units for $26,400, Call-Mart has 8,000 units costing $34,400 ($8,000 plus $26,400) on hand. The average unit cost is $34,400 divided by 8,000, or $4.30. Call-Mart uses this unit cost in costing withdrawals until it makes another purchase. At that point, Call-Mart computes a new average unit cost. Accordingly, the company shows the cost of the 4,000 units withdrawn on March 19 at $4.30, for a total cost of goods sold of $17,200. On March 30, following the purchase of 2,000 units for $9,500, Call-Mart determines a new unit cost of $4.45, for an ending inventory of $26,700.

Companies often use average cost methods for practical rather than conceptual reasons. These methods are simple to apply and objective. They are not as subject to income manipulation as some of the other inventory pricing methods. In addition, proponents of the average cost methods reason that measuring a specific physical flow of inventory is often impossible. Therefore, it is better to cost items on an average-price basis. This argument is particularly persuasive when dealing with similar inventory items.

The FIFO (first-in, first-out) method assumes that a company uses goods in the order in which it purchases them. In other words, the FIFO method assumes that the first goods purchased are the first used (in a manufacturing concern) or the first sold (in a merchandising concern). The inventory remaining must therefore represent the most recent purchases.

To illustrate, assume that Call-Mart uses the periodic inventory system. It determines its cost of the ending inventory by taking the cost of the most recent purchase and working back until it accounts for all units in the inventory. Call-Mart determines its ending inventory and cost of goods sold as shown in Illustration 8-15.

If Call-Mart instead uses a perpetual inventory system in quantities and dollars, it attaches a cost figure to each withdrawal. Then the cost of the 4,000 units removed on March 19 consists of the cost of the items purchased on March 2 and March 15. Illustration 8-16 shows the inventory on a FIFO basis perpetual system for Call-Mart.

Here, the ending inventory is $27,100, and the cost of goods sold is $16,800 [(2,000 @ 4.00) + (2,000 @ $4.40)].

Notice that in these two FIFO examples, the cost of goods sold ($16,800) and ending inventory ($27,100) are the same. In all cases where FIFO is used, the inventory and cost of goods sold would be the same at the end of the month whether a perpetual or periodic system is used. Why? Because the same costs will always be first in and, therefore, first out. This is true whether a company computes cost of goods sold as it sells goods throughout the accounting period (the perpetual system) or as a residual at the end of the accounting period (the periodic system).

One objective of FIFO is to approximate the physical flow of goods. When the physical flow of goods is actually first-in, first-out, the FIFO method closely approximates specific identification. At the same time, it prevents manipulation of income. With FIFO, a company cannot pick a certain cost item to charge to expense.

Another advantage of the FIFO method is that the ending inventory is close to current cost. Because the first goods in are the first goods out, the ending inventory amount consists of the most recent purchases. This is particularly true with rapid inventory turnover. This approach generally approximates replacement cost on the balance sheet when price changes have not occurred since the most recent purchases.

However, the FIFO method fails to match current costs against current revenues on the income statement. A company charges the oldest costs against the more current revenue, possibly distorting gross profit and net income.

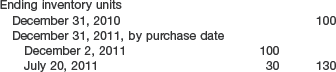

The LIFO (last-in, first-out) method matches the cost of the last goods purchased against revenue. If Call-Mart Inc. uses a periodic inventory system, it assumes that the cost of the total quantity sold or issued during the month comes from the most recent purchases. Call-Mart prices the ending inventory by using the total units as a basis of computation and disregards the exact dates of sales or issuances. For example, Call-Mart would assume that the cost of the 4,000 units withdrawn absorbed the 2,000 units purchased on March 30 and 2,000 of the 6,000 units purchased on March 15. Illustration 8-17 shows how Call-Mart computes the inventory and related cost of goods sold, using the periodic inventory method.

If Call-Mart keeps a perpetual inventory record in quantities and dollars, use of the LIFO method results in different ending inventory and cost of goods sold amounts than the amounts calculated under the periodic method. Illustration 8-18 shows these differences under the perpetual method.

The month-end periodic inventory computation presented in Illustration 8-17 (inventory $25,600 and cost of goods sold $18,300) shows a different amount from the perpetual inventory computation (inventory $26,300 and cost of goods sold $17,600). The periodic system matches the total withdrawals for the month with the total purchases for the month in applying the last-in, first-out method. In contrast, the perpetual system matches each withdrawal with the immediately preceding purchases. In effect, the periodic computation assumed that Call-Mart included the cost of the goods that it purchased on March 30 in the sale or issue on March 19.

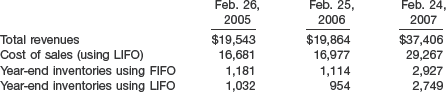

Many companies use LIFO for tax and external reporting purposes. However, they maintain a FIFO, average cost, or standard cost system for internal reporting purposes. There are several reasons to do so: (1) Companies often base their pricing decisions on a FIFO, average, or standard cost assumption, rather than on a LIFO basis. (2) Recordkeeping on some other basis is easier because the LIFO assumption usually does not approximate the physical flow of the product. (3) Profit-sharing and other bonus arrangements often depend on a non-LIFO inventory assumption. Finally, (4) the use of a pure LIFO system is troublesome for interim periods, which require estimates of year-end quantities and prices.

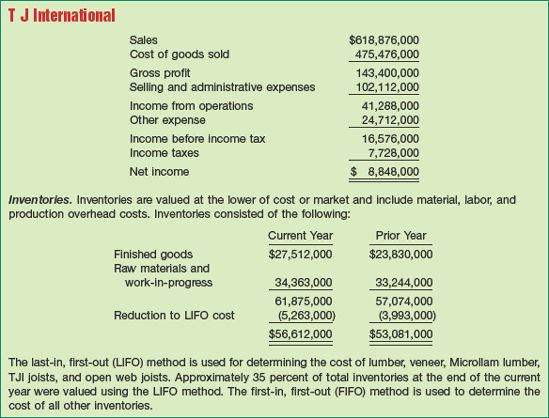

The difference between the inventory method used for internal reporting purposes and LIFO is the Allowance to Reduce Inventory to LIFO or the LIFO reserve. The change in the allowance balance from one period to the next is the LIFO effect. The LIFO effect is the adjustment that companies must make to the accounting records in a given year.

To illustrate, assume that Acme Boot Company uses the FIFO method for internal reporting purposes and LIFO for external reporting purposes. At January 1, 2010, the Allowance to Reduce Inventory to LIFO balance is $20,000. At December 31, 2010, the balance should be $50,000. As a result, Acme Boot realizes a LIFO effect of $30,000 and makes the following entry at year-end.

Acme Boot deducts the Allowance to Reduce Inventory to LIFO from inventory to ensure that it states the inventory on a LIFO basis at year-end.

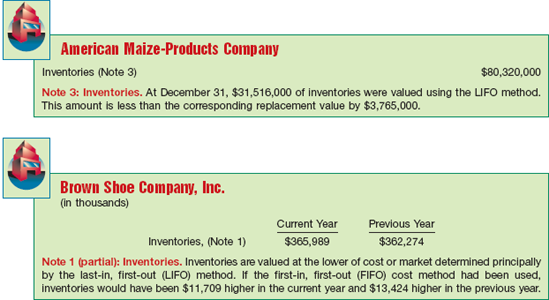

Companies should disclose either the LIFO reserve or the replacement cost of the inventory, as shown in Illustration 8-19.[104]

Investors commonly use the current ratio to evaluate a company's liquidity. They compute the current ratio as current assets divided by current liabilities. A higher current ratio indicates that a company is better able to meet its current obligations when they come due. However, it is not meaningful to compare the current ratio for a company using LIFO to one for a company using FIFO. It would be like comparing apples to oranges, since the two companies measure inventory (and cost of goods sold) differently.

To make the current ratio comparable on an apples-to-apples basis, analysts use the LIFO reserve. The following adjustments should do the trick:

| Inventory Adjustment: LIFO inventory + LIFO reserve = FIFO inventory |

(For cost of goods sold, deduct the change in the LIFO reserve from LIFO cost of goods sold to yield the comparable FIFO amount.)

For Brown Shoe, Inc. (see Illustration 8-19), with current assets of $487.8 million and current liabilities of $217.8 million, the current ratio using LIFO is: $487.8 ÷ $217.8 = 2.2. After adjusting for the LIFO effect, Brown's current ratio under FIFO would be: ($487.8 + $11.7) ÷ $217.8 = 2.3.

Thus, without the LIFO adjustment, the Brown Shoe current ratio is understated.

Up to this point, we have emphasized a specific-goods approach to costing LIFO inventories (also called traditional LIFO or unit LIFO). This approach is often unrealistic for two reasons:

When a company has many different inventory items, the accounting cost of tracking each inventory item is expensive.

Erosion of the LIFO inventory can easily occur. Referred to as LIFO liquidation, this often distorts net income and leads to substantial tax payments.

To understand the LIFO liquidation problem, assume that Basler Co. has 30,000 pounds of steel in its inventory on December 31, 2010, with cost determined on a specific-goods LIFO approach.

As indicated, the ending 2010 inventory for Basler comprises costs from past periods. These costs are called layers (increases from period to period). The first layer is identified as the base layer. Illustration 8-20 (on the next page) shows the layers for Basler.

Note the increased price of steel over the 4-year period. In 2011, due to metal shortages, Basler had to liquidate much of its inventory (a LIFO liquidation). At the end of 2011, only 6,000 pounds of steel remained in inventory. Because the company uses LIFO, Basler liquidates the most recent layer, 2010, first, followed by the 2009 layer, and so on. The result: Basler matches costs from preceding periods against sales revenues reported in current dollars. As Illustration 8-21 shows, this leads to a distortion in net income and increased taxable income in the current period. Unfortunately, LIFO liquidations can occur frequently when using a specific-goods LIFO approach.

To alleviate the LIFO liquidation problems and to simplify the accounting, companies can combine goods into pools. A pool groups items of a similar nature. Thus, instead of only identical units, a company combines, and counts as a group, a number of similar units or products. This method, the specific-goods pooled LIFO approach, usually results in fewer LIFO liquidations. Why? Because the reduction of one quantity in the pool may be offset by an increase in another.

The specific-goods pooled LIFO approach eliminates some of the disadvantages of the specific-goods (traditional) accounting for LIFO inventories. This pooled approach, using quantities as its measurement basis, however, creates other problems.

First, most companies continually change the mix of their products, materials, and production methods. As a result, in employing a pooled approach using quantities, companies must continually redefine the pools. This can be time consuming and costly. Second, even when practical, the approach often results in an erosion ("LIFO liquidation") of the layers, thereby losing much of the LIFO costing benefit. An erosion of the layers results due to replacement of a specific good or material in the pool with another good or material. The new item may not be similar enough to be treated as part of the old pool. Therefore a company may need to recognize any inflationary profit deferred on the old goods as it replaces them.

The dollar-value LIFO method overcomes the problems of redefining pools and eroding layers. The dollar-value LIFO method determines and measures any increases and decreases in a pool in terms of total dollar value, not the physical quantity of the goods in the inventory pool.

Such an approach has two important advantages over the specific-goods pooled approach. First, companies may include a broader range of goods in a dollar-value LIFO pool. Second, a dollar-value LIFO pool permits replacement of goods that are similar items, similar in use, or interchangeable. (In contrast, a specific-goods LIFO pool only allows replacement of items that are substantially identical.)

Thus, dollar-value LIFO techniques help protect LIFO layers from erosion. Because of this advantage, companies frequently use the dollar-value LIFO method in practice.[105] Companies use the more traditional LIFO approaches only when dealing with few goods and expecting little change in product mix.

Under the dollar-value LIFO method, one pool may contain the entire inventory. However, companies generally use several pools.[106] In general, the more goods included in a pool, the more likely that increases in the quantities of some goods will offset decreases in other goods in the same pool. Thus, companies avoid liquidation of the LIFO layers. It follows that having fewer pools means less cost and less chance of a reduction of a LIFO layer.[107]

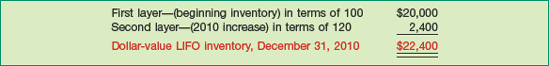

To illustrate how the dollar-value LIFO method works, assume that Enrico Company first adopts dollar-value LIFO on December 31, 2009 (base period). The inventory at current prices on that date was $20,000. The inventory on December 31, 2010, at current prices is $26,400.

Can we conclude that Enrico's inventory quantities increased 32 percent during the year ($26,400 ÷ $20,000 = 132%)? First, we need to ask: What is the value of the ending inventory in terms of beginning-of-the-year prices? Assuming that prices have increased 20 percent during the year, the ending inventory at beginning-of-the-year prices amounts to $22,000 ($26,400 ÷ 120%). Therefore, the inventory quantity has increased only 10 percent, or from $20,000 to $22,000 in terms of beginning-of-the-year prices.

The next step is to price this real-dollar quantity increase. This real-dollar quantity increase of $2,000 valued at year-end prices is $2,400 (120% × $2,000). This increment (layer) of $2,400, when added to the beginning inventory of $20,000, totals $22,400 for the December 31, 2010, inventory, as shown below.

Note that a layer forms only when the ending inventory at base-year prices exceeds the beginning inventory at base-year prices. And only when a new layer forms must Enrico compute a new index.

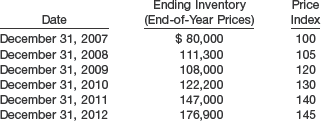

To illustrate the use of the dollar-value LIFO method in a more complex situation, assume that Bismark Company develops the following information.

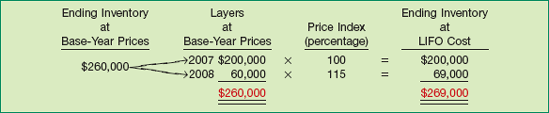

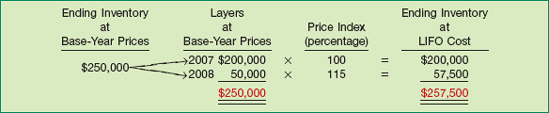

At December 31, 2007, Bismark computes the ending inventory under dollar-value LIFO as $200,000, as Illustration 8-22 shows.

At December 31, 2008, a comparison of the ending inventory at base-year prices ($260,000) with the beginning inventory at base-year prices ($200,000) indicates that the quantity of goods (in base-year prices) increased $60,000 ($260,000 − $200,000). Bismark prices this increment (layer) at the 2008 index of 115 percent to arrive at a new layer of $69,000. Ending inventory for 2008 is $269,000, composed of the beginning inventory of $200,000 and the new layer of $69,000. Illustration 8-23 shows the computations.

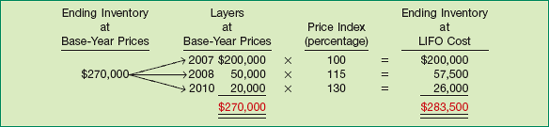

At December 31, 2009, a comparison of the ending inventory at base-year prices ($250,000) with the beginning inventory at base-year prices ($260,000) indicates a decrease in the quantity of goods of $10,000 ($250,000 − $260,000). If the ending inventory at base-year prices is less than the beginning inventory at base-year prices, a company must subtract the decrease from the most recently added layer. When a decrease occurs, the company "peels off" previous layers at the prices in existence when it added the layers. In Bismark's situation, this means that it removes $10,000 in base-year prices from the 2008 layer of $60,000 at base-year prices. It values the balance of $50,000 ($60,000 − $10,000) at base-year prices at the 2008 price index of 115 percent. As a result, it now values this 2008 layer at $57,500 ($50,000 × 115%). Therefore, Bismark computes the ending inventory at $257,500, consisting of the beginning inventory of $200,000 and the second layer of $57,500. Illustration 8-24 shows the computations for 2009.

Note that if Bismark eliminates a layer or base (or portion thereof), it cannot rebuild it in future periods. That is, the layer is gone forever.

At December 31, 2010, a comparison of the ending inventory at base-year prices ($270,000) with the beginning inventory at base-year prices ($250,000) indicates an increase in the quantity of goods (in base-year prices) of $20,000 ($270,000 − $250,000). After converting the $20,000 increase to the 2010 price index, the ending inventory is $283,500, composed of the beginning layer of $200,000, a 2008 layer of $57,500, and a 2010 layer of $26,000 ($20,000 × 130%). Illustration 8-25 shows this computation.

The ending inventory at base-year prices must always equal the total of the layers at base-year prices. Checking that this situation exists will help to ensure correct dollar-value computations.

Obviously, price changes are critical in dollar-value LIFO. How do companies determine the price indexes? Many companies use the general price-level index that the federal government prepares and publishes each month. The most popular general external price-level index is the Consumer Price Index for Urban Consumers (CPI-U).[108] Companies also use more-specific external price indexes. For instance, various organizations compute and publish daily indexes for most commodities (gold, silver, other metals, corn, wheat, and other farm products). Many trade associations prepare indexes for specific product lines or industries. Any of these indexes may be used for dollar-value LIFO purposes.

When a relevant specific external price index is not readily available, a company may compute its own specific internal price index. The desired approach is to price ending inventory at the most current cost. Therefore, a company that chose to compute its own specific internal price index would ordinarily determine current cost by referring to the actual cost of the goods it most recently had purchased. The price index provides a measure of the change in price or cost levels between the base year and the current year. The company then computes the index for each year after the base year. The general formula for computing the index is as follows.

This approach is generally referred to as the double-extension method. As its name implies, the value of the units in inventory is extended at both base-year prices and current-year prices.

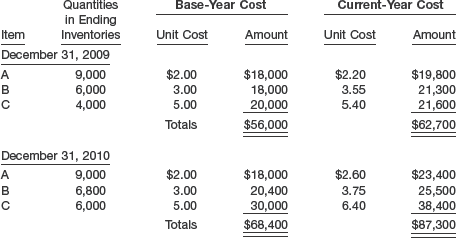

To illustrate this computation, assume that Toledo Company's base-year inventory (January 1, 2010) consisted of the following.

Examination of the ending inventory indicates that the company holds 3,000 units of Item A and 6,000 units of Item B on December 31, 2010. The most recent actual purchases related to these items were as follows.

Toledo double-extends the inventory as shown in Illustration 8-27.

After the inventories are double-extended, Toledo uses the formula in Illustration 8-26 to develop the index for the current year (2010), as follows.

Toledo then applies this index (121.74%) to the layer added in 2010. Note in this illustration that Toledo used the most recent actual purchases to determine current cost; alternatively, it could have used other approaches such as FIFO and average cost. Whichever flow assumption is adopted, a company must use it consistently from one period to another.

Use of the double-extension method is time consuming and difficult where substantial technological change has occurred or where many items are involved. That is, as time passes, the company must determine a new base-year cost for new products, and must keep a base-year cost for each inventory item.[109]

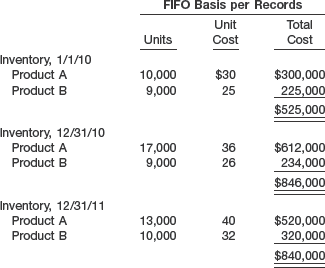

As indicated, significant differences can arise in inventory measured according to current cost and dollar-value LIFO. Let's look at an additional summary example.

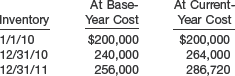

Truman Company uses the dollar-value LIFO method of computing its inventory. Inventory for the last three years is as shown below:

The values of the 2008, 2009, and 2010 inventories using the dollar-value LIFO method are as follows.

Consistent with LIFO costing in times of rising prices, the dollar-value LIFO inventory amount is less than inventory stated at end-of-year prices. The company did not add layers at the 2010 prices. This is because the increase in inventory at end-of-year (current) prices was primarily due to higher prices. Also, establishing the LIFO layers based on price-adjusted dollars relative to base-year layers reduces the likelihood of a LIFO liquidation.

We present three different approaches to computing LIFO inventories in this chapter—specific-goods LIFO, specific-goods pooled LIFO, and dollar-value LIFO. As we indicated earlier, the use of the specific-goods LIFO is unrealistic. Most companies have numerous goods in inventory at the end of a period. Costing (pricing) them on a unit basis is extremely expensive and time consuming.

The specific-goods pooled LIFO approach reduces recordkeeping and clerical costs. In addition, it is more difficult to erode the layers because the reduction of one quantity in the pool may be offset by an increase in another. Nonetheless, the pooled approach using quantities as its measurement basis can lead to untimely LIFO liquidations.

As a result, most companies using a LIFO system employ dollar-value LIFO. Although the approach appears complex, the logic and the computations are actually quite simple, after determining an appropriate index.

However, problems do exist with the dollar-value LIFO method. The selection of the items to be put in a pool can be subjective.[110] Such a determination, however, is extremely important because manipulation of the items in a pool without conceptual justification can affect reported net income. For example, the SEC noted that some companies have set up pools that are easy to liquidate. As a result, to increase income, a company simply decreases inventory, thereby matching low-cost inventory items to current revenues.

To curb this practice, the SEC has taken a much harder line on the number of pools that companies may establish. In a well-publicized case, Stauffer Chemical Company increased the number of LIFO pools from 8 to 280, boosting its net income by $16,515,000 or approximately 13 percent.[111] Stauffer justified the change in its Annual Report on the basis of "achieving a better matching of cost and revenue." The SEC required Stauffer to reduce the number of its inventory pools, contending that some pools were inappropriate and alleging income manipulation.

One obvious advantage of LIFO approaches is that the LIFO cost flow often approximates the physical flow of the goods in and out of inventory. For instance, in a coal pile, the last coal in is the first coal out because it is on the top of the pile. The coal remover is not going to take the coal from the bottom of the pile! The coal taken first is the coal placed on the pile last.

However, this is one of only a few situations where the actual physical flow corresponds to LIFO. Therefore most adherents of LIFO use other arguments for its widespread use, as follows.

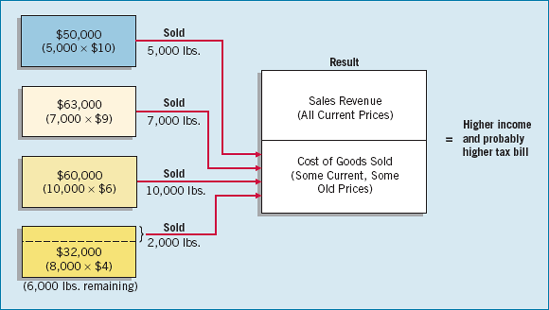

LIFO matches the more recent costs against current revenues to provide a better measure of current earnings. During periods of inflation, many challenge the quality of non-LIFO earnings, noting that failing to match current costs against current revenues creates transitory or "paper" profits ("inventory profits"). Inventory profits occur when the inventory costs matched against sales are less than the inventory replacement cost. This results in understating the cost of goods sold and overstating profit. Using LIFO (rather than a method such as FIFO) matches current costs against revenues, thereby reducing inventory profits.

LIFO's popularity mainly stems from its tax benefits. As long as the price level increases and inventory quantities do not decrease, a deferral of income tax occurs. Why? Because a company matches the items it most recently purchased (at the higher price level) against revenues. For example, when Fuqua Industries switched to LIFO, it realized a tax savings of about $4 million. Even if the price level decreases later, the company still temporarily deferred its income taxes. Thus, use of LIFO in such situations improves a company's cash flow.[112]

The tax law requires that if a company uses LIFO for tax purposes, it must also use LIFO for financial accounting purposes[113] (although neither tax law nor GAAP requires a company to pool its inventories in the same manner for book and tax purposes). This requirement is often referred to as the LIFO conformity rule. Other inventory valuation methods do not have this requirement.

With LIFO, future price declines will not substantially affect a company's future reported earnings. The reason: Since the company records the most recent inventory as sold first, there is not much ending inventory at high prices vulnerable to a price decline. Thus LIFO eliminates or substantially minimizes write-downs to market as a result of price decreases. In contrast, inventory costed under FIFO is more vulnerable to price declines, which can reduce net income substantially.

Despite its advantages, LIFO has the following drawbacks.

Many corporate managers view the lower profits reported under the LIFO method in inflationary times as a distinct disadvantage. They would rather have higher reported profits than lower taxes. Some fear that investors may misunderstand an accounting change to LIFO, and that the lower profits may cause the price of the company's stock to fall.

LIFO may have a distorting effect on a company's balance sheet. The inventory valuation is normally outdated because the oldest costs remain in inventory. This understatement makes the working capital position of the company appear worse than it really is. A good example is Caterpillar, which uses LIFO costing for most of its inventory, valued at $7.2 billion at year-end 2007. Under FIFO costing, Caterpillar's inventories have a value of $9.8 billion—almost 36 percent higher than the LIFO amount.

The magnitude and direction of this variation between the carrying amount of inventory and its current price depend on the degree and direction of the price changes and the amount of inventory turnover. The combined effect of rising product prices and avoidance of inventory liquidations increases the difference between the inventory carrying value at LIFO and current prices of that inventory. This magnifies the balance sheet distortion attributed to the use of LIFO.

LIFO does not approximate the physical flow of the items except in specific situations (such as the coal pile discussed earlier). Originally companies could use LIFO only in certain circumstances. This situation has changed over the years. Now, physical flow characteristics no longer determine whether a company may employ LIFO.

If a company eliminates the base or layers of old costs, it may match old, irrelevant costs against current revenues. A distortion in reported income for a given period may result, as well as detrimental income tax consequences.[114]

Because of the liquidation problem, LIFO may cause poor buying habits. A company may simply purchase more goods and match these goods against revenue to avoid charging the old costs to expense. Furthermore, recall that with LIFO, a company may attempt to manipulate its net income at the end of the year simply by altering its pattern of purchases.[115]

One survey uncovered the following reasons why companies reject LIFO.[116]

How does a company choose among the various inventory methods? Although no absolute rules can be stated, preferability for LIFO usually occurs in either of the following circumstances: (1) if selling prices and revenues have been increasing faster than costs, thereby distorting income, and (2) in situations where LIFO has been traditional, such as department stores and industries where a fairly constant "base stock" is present (such as refining, chemicals, and glass).[117]

Conversely, LIFO is probably inappropriate in the following circumstances: (1) where prices tend to lag behind costs; (2) in situations where specific identification is traditional, such as in the sale of automobiles, farm equipment, art, and antique jewelry; or (3) where unit costs tend to decrease as production increases, thereby nullifying the tax benefit that LIFO might provide.[118]

Tax consequences are another consideration. Switching from FIFO to LIFO usually results in an immediate tax benefit. However, switching from LIFO to FIFO can result in a substantial tax burden. For example, when Chrysler changed from LIFO to FIFO, it became responsible for an additional $53 million in taxes that the company had deferred over 14 years of LIFO inventory valuation. Why, then, would Chrysler, and other companies, change to FIFO? The major reason was the profit crunch of that era. Although Chrysler showed a loss of $7.6 million after the switch, the loss would have been $20 million more if the company had not changed its inventory valuation from LIFO to FIFO.

It is questionable whether companies should switch from LIFO to FIFO for the sole purpose of increasing reported earnings. Intuitively, one would assume that companies with higher reported earnings would have a higher share valuation (common stock price). However, some studies have indicated that the users of financial data exhibit a much higher sophistication than might be expected. Share prices are the same and, in some cases, even higher under LIFO in spite of lower reported earnings.[119]

The concern about reduced income resulting from adoption of LIFO has even less substance now because the IRS has relaxed the LIFO conformity rule which requires a company employing LIFO for tax purposes to use it for book purposes as well. The IRS has relaxed restrictions against providing non-LIFO income numbers as supplementary information. As a result, companies now provide supplemental non-LIFO disclosures. While not intended to override the basic LIFO method adopted for financial reporting, these disclosures may be useful in comparing operating income and working capital with companies not on LIFO.

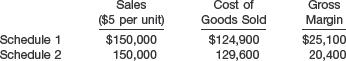

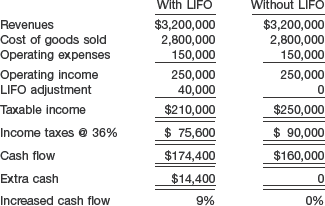

For example, JCPenney, Inc., a LIFO user, presented the information in its annual report as shown in Illustration 8-30.

Relaxation of the LIFO conformity rule has led some companies to select LIFO as their inventory valuation method because they will be able to disclose FIFO income numbers in the financial reports if they so desire.[120]

Companies often combine inventory methods. For example, John Deere uses LIFO for most of its inventories, and prices the remainder using FIFO. Hershey Foods follows the same practice. One reason for these practices is that certain product lines can be highly susceptible to deflation instead of inflation. In addition, if the level of inventory is unstable, unwanted involuntary liquidations may result in certain product lines if using LIFO. Finally, for high inventory turnover in certain product lines, a company cannot justify LIFO's additional recordkeeping and expense. In such cases, a company often uses average cost because it is easy to compute.[121]

Although a company may use a variety of inventory methods to assist in accurate computation of net income, once it selects a pricing method, it must apply it consistently thereafter. If conditions indicate that the inventory pricing method in use is unsuitable, the company must seriously consider all other possibilities before selecting another method. It should clearly explain any change and disclose its effect in the financial statements.

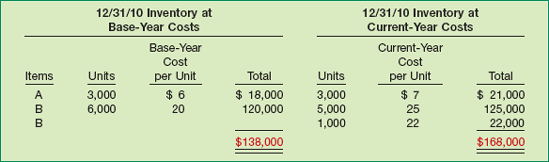

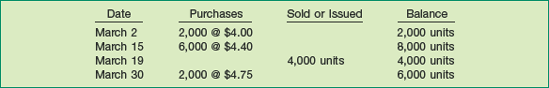

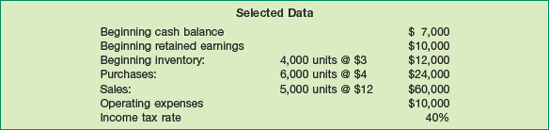

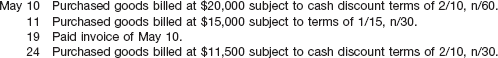

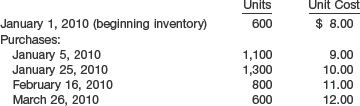

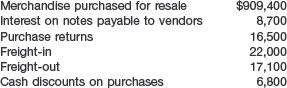

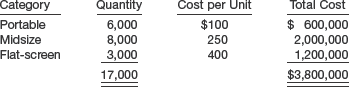

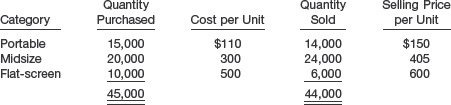

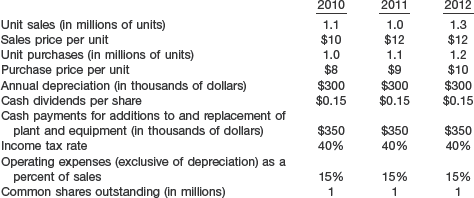

The preceding sections of this chapter described a number of inventory valuation methods. Here we present a brief summary of the three major inventory methods to show the effects these valuation methods have on the financial statements. This comparison assumes periodic inventory procedures and the following selected data.

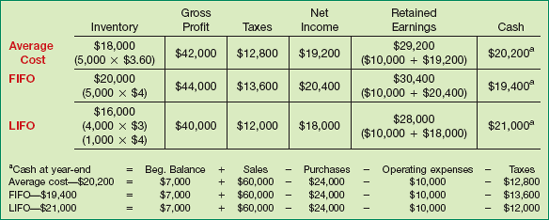

Illustration 8-31 shows the comparative results on net income of the use of average cost, FIFO, and LIFO.

Notice that gross profit and net income are lowest under LIFO, highest under FIFO, and somewhere in the middle under average cost.

Illustration 8-32 shows the final balances of selected items at the end of the period.

LIFO results in the highest cash balance at year-end (because taxes are lower). This example assumes that prices are rising. The opposite result occurs if prices are declining.

FASB Codification References

FASB ASC 470-40-05. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Product Financing Arrangements," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 49 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1981).]

FASB ASC 605-15-15. [Predecessor literature: "Revenue Recognition When Right of Return Exists," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 48 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1981).]

FASB ASC 330-10-30-7. [Predecessor literature: "Inventory Costs: An Amendment of ARB No. 43, Chapter 4," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 151 (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB 2004).]

FASB ASC 835-20-05. [Predecessor literature: "Capitalization of Interest Cost," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 34 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1979).]

FASB ASC 645-45-05. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Shipping and Handling Fees and Costs," EITF No. 00–10 (2000).]

FASB ASC 330-10-30. [Predecessor literature: "Restatement and Revision of Accounting Research Bulletins," Accounting Research Bulletin No. 43 (New York: AICPA, 1953), Ch. 4, Statement 4.]

In what ways are the inventory accounts of a retailing company different from those of a manufacturing company?

Why should inventories be included in (a) a statement of financial position and (b) the computation of net income?

What is the difference between a perpetual inventory and a physical inventory? If a company maintains a perpetual inventory, should its physical inventory at any date be equal to the amount indicated by the perpetual inventory records? Why?

Mishima, Inc. indicated in a recent annual report that approximately $19 million of merchandise was received on consignment. Should Mishima, Inc. report this amount on its balance sheet? Explain.

What is a product financing arrangement? How should product financing arrangements be reported in the financial statements?

Where, if at all, should the following items be classified on a balance sheet?

At the balance sheet date Clarkson Company held title to goods in transit amounting to $214,000. This amount was omitted from the purchases figure for the year and also from the ending inventory. What is the effect of this omission on the net income for the year as calculated when the books are closed? What is the effect on the company's financial position as shown in its balance sheet? Is materiality a factor in determining whether an adjustment for this item should be made?

Define "cost" as applied to the valuation of inventories.

Distinguish between product costs and period costs as they relate to inventory.

Ford Motor Co. is considering alternate methods of accounting for the cash discounts it takes when paying suppliers promptly. One method suggested was to report these discounts as financial income when payments are made. Comment on the propriety of this approach.

Zonker Inc. purchases 500 units of an item at an invoice cost of $30,000. What is the cost per unit? If the goods are shipped f.o.b. shipping point and the freight bill was $1,500, what is the cost per unit if Zonker Inc. pays the freight charges? If these items were bought on 2/10, n/30 terms and the invoice and the freight bill were paid within the 10-day period, what would be the cost per unit?

Specific identification is sometimes said to be the ideal method of assigning cost to inventory and to cost of goods sold. Briefly indicate the arguments for and against this method of inventory valuation.

FIFO, weighted-average, and LIFO methods are often used instead of specific identification for inventory valuation purposes. Compare these methods with the specific identification method, discussing the theoretical propriety of each method in the determination of income and asset valuation.

How might a company obtain a price index in order to apply dollar-value LIFO?

Describe the LIFO double-extension method. Using the following information, compute the index at December 31, 2010, applying the double-extension method to a LIFO pool consisting of 25,500 units of product A and 10,350 units of product B. The base-year cost of product A is $10.20 and of product B is $37.00. The price at December 31, 2010, for product A is $21.00 and for product B is $45.60.

As compared with the FIFO method of costing inventories, does the LIFO method result in a larger or smaller net income in a period of rising prices? What is the comparative effect on net income in a period of falling prices?

What is the dollar-value method of LIFO inventory valuation? What advantage does the dollar-value method have over the specific goods approach of LIFO inventory valuation? Why will the traditional LIFO inventory costing method and the dollar-value LIFO inventory costing method produce different inventory valuations if the composition of the inventory base changes?

Explain the following terms.

LIFO layer.

LIFO reserve.

LIFO effect.

On December 31, 2009, the inventory of Powhattan Company amounts to $800,000. During 2010, the company decides to use the dollar-value LIFO method of costing inventories. On December 31, 2010, the inventory is $1,053,000 at December 31, 2010, prices. Using the December 31, 2009, price level of 100 and the December 31, 2010, price level of 108, compute the inventory value at December 31, 2010, under the dollar-value LIFO method.

In an article that appeared in the Wall Street Journal, the phrases "phantom (paper) profits" and "high LIFO profits" through involuntary liquidation were used. Explain these phrases.

Cash

$ 190,000

Equipment (net)

1,100,000

Prepaid insurance

41,000

Raw materials

335,000

Work in process

$200,000

Receivables (net)

400,000

Patents

110,000

Finished goods

170,000

Prepare the current assets section of the December 31 balance sheet.

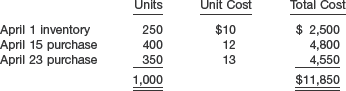

Compute the April 30 inventory and the April cost of goods sold using the average cost method.

Instructions

Compute the value of the 2010 and 2011 inventories using the dollar-value LIFO method.

Goods sold on an installment basis (bad debts can be reasonably estimated).

Goods out on consignment at another company's store.

Goods purchased f.o.b. shipping point that are in transit at December 31.

Goods purchased f.o.b. destination that are in transit at December 31.

Goods sold to another company, for which our company has signed an agreement to repurchase at a set price that covers all costs related to the inventory.

Goods sold where large returns are predictable.

Goods sold f.o.b. shipping point that are in transit at December 31.

Freight charges on goods purchased.

Interest costs incurred for inventories that are routinely manufactured.

Materials on hand not yet placed into production by a manufacturing firm.

Costs incurred to advertise goods held for resale.

Office supplies.

Raw materials on which a manufacturing firm has started production, but which are not completely processed.

Factory supplies.

Goods held on consignment from another company.

Costs identified with units completed by a manufacturing firm, but not yet sold.

Goods sold f.o.b. destination that are in transit at December 31.

Short-term investments in stocks and bonds that will be resold in the near future.

Instructions

Indicate which of these items would typically be reported as inventory in the financial statements. If an item should not be reported as inventory, indicate how it should be reported in the financial statements.

Merchandise of $61,000 which is held by Garza on consignment. The consignor is the Bontemps Company.

Merchandise costing $33,000 which was shipped by Garza f.o.b. destination to a customer on December 31, 2010. The customer was expected to receive the merchandise on January 6, 2011.

Merchandise costing $46,000 which was shipped by Garza f.o.b. shipping point to a customer on December 29, 2010. The customer was scheduled to receive the merchandise on January 2, 2011.

Merchandise costing $73,000 shipped by a vendor f.o.b. destination on December 30, 2010, and received by Garza on January 4, 2011.

Merchandise costing $51,000 shipped by a vendor f.o.b. shipping point on December 31, 2010, and received by Garza on January 5, 2011.

Instructions

Based on the above information, calculate the amount that should appear on Garza's balance sheet at December 31, 2010, for inventory.

A special machine, fabricated to order for a customer, was finished and specifically segregated in the back part of the shipping room on December 31, 2010. The customer was billed on that date and the machine excluded from inventory although it was shipped on January 4, 2011.

Merchandise costing $2,800 was received on January 3, 2011, and the related purchase invoice recorded January 5. The invoice showed the shipment was made on December 29, 2010, f.o.b. destination.

A packing case containing a product costing $3,400 was standing in the shipping room when the physical inventory was taken. It was not included in the inventory because it was marked "Hold for shipping instructions." Your investigation revealed that the customer's order was dated December 18, 2010, but that the case was shipped and the customer billed on January 10, 2011. The product was a stock item of your client.

Merchandise costing $720 was received on December 28, 2010, and the invoice was not recorded. You located it in the hands of the purchasing agent; it was marked "on consignment."

Merchandise received on January 6, 2011, costing $680 was entered in the purchase journal on January 7, 2011. The invoice showed shipment was made f.o.b. supplier's warehouse on December 31, 2010. Because it was not on hand at December 31, it was not included in inventory.

Instructions

Assuming that each of the amounts is material, state whether the merchandise should be included in the client's inventory, and give your reason for your decision on each item.

An invoice for $8,100, terms f.o.b. destination, was received and entered January 2, 2011. The receiving report shows that the materials were received December 28, 2010.

Materials costing $7,300 were returned to the supplier on December 29, 2010, and were shipped f.o.b. shipping point. The return was entered on that date, even though the materials are not expected to reach the supplier's place of business until January 6, 2011.

Materials costing $28,000, shipped f.o.b. destination, were not entered by December 31, 2010, "because they were in a railroad car on the company's siding on that date and had not been unloaded."

An invoice for $7,500, terms f.o.b. shipping point, was received and entered December 30, 2010. The receiving report shows that the materials were received January 4, 2011, and the bill of lading shows that they were shipped January 2, 2011.

Materials costing $19,800 were received December 30, 2010, but no entry was made for them because "they were ordered with a specified delivery of no earlier than January 10, 2011."

Instructions

Prepare correcting general journal entries required at December 31, 2010, assuming that the books have not been closed.

Werth uses the periodic method of recording inventory. A physical count reveals $234,890 of inventory on hand at December 31, 2010.

Not included in the physical count of inventory is $10,420 of merchandise purchased on December 15 from Browser. This merchandise was shipped f.o.b. shipping point on December 29 and arrived in January. The invoice arrived and was recorded on December 31.

Included in inventory is merchandise sold to Bubbey on December 30, f.o.b. destination. This merchandise was shipped after it was counted. The invoice was prepared and recorded as a sale on account for $12,800 on December 31. The merchandise cost $7,350, and Bubbey received it on January 3.

Included in inventory was merchandise received from Dudley on December 31 with an invoice price of $15,630. The merchandise was shipped f.o.b. destination. The invoice, which has not yet arrived, has not been recorded.