Although it's always wise to take the time to make the best photos possible while shooting, Aperture has a lot of tools that you can use to make your images even better. With a click of a button, setting a few sliders, or applying a few brushstrokes you can optimize your shots and add impact without spending excessive amounts of time on your computer. That way you can make the most of your images and still have time to go about your life!

Reprocessing Masters for Aperture 3

Straightening an Image

Cropping Images

Reducing Red Eye

Using the Adjustments Inspector

Using Quick Brushes

Creating and Using Adjustment Presets

Using an External Editor

Using Third-Party Editing Plug-Ins

Apple modified the algorithms it uses in Aperture 3 for better noise processing, sharpening, and highlight recovery with RAW files. However, anytime algorithms change, the appearance of images you've already processed may change when you update them to the new algorithms. Apple realizes that even though the new algorithms enable you to perform some great new functions including selectively brushing adjustments in or out, you may not want the appearance of all your images to change when you upgrade to Aperture 3. Therefore when you upgrade your Aperture or Aperture 2 libraries, the images use their original algorithms by default, so that their appearance remains the same. You then have the option to upgrade images one at a time, or to update groups of images, projects, or the entire library. Of course, all new images that you import into your Aperture 3 library automatically use the new algorithms.

Note

If the image has already been reprocessed or was imported new into Aperture 3, the Reprocess Master option will not appear in the Adjustments panel.

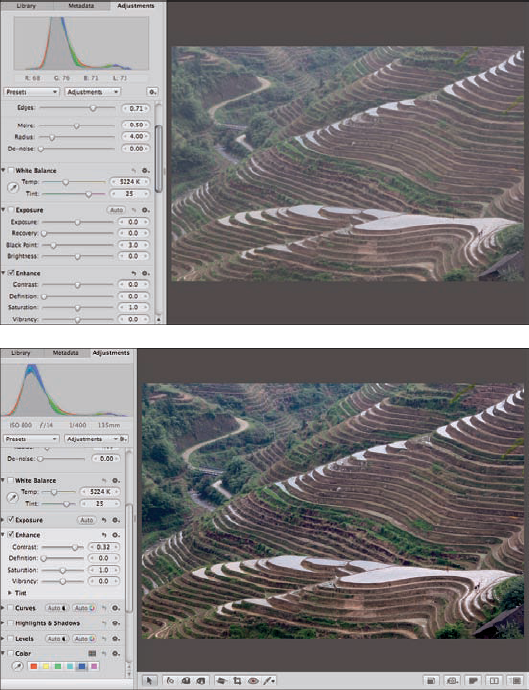

To upgrade a single image from an older library that you converted to an Aperture 3 library, choose the image and choose the Adjustments panel, as shown in Figure 6.1, then click Reprocess.

To reprocess a selection of images or an entire project, album, book, slide show, and so on, do the following:

Figure 6.1. If an image was processed using an earlier version of Aperture, the Reprocess option will appear in the Adjustments panel.

Select the images or project, album, book, slide show, and so forth, that you want to reprocess.

Choose Photos

In the new dialog, specify whether to reprocess all the images or only those with or without adjustments, and whether you want to create a new version for each image or just reprocess the original version.

Figure 6.2. Specify the criteria to use while reprocessing images including whether to create a new reprocessed version while retaining the original version.

You can opt to reprocess the entire library by following the same steps just described but choosing Photos in the Library Inspector initially.

Warning

Reprocessing images takes time, so the more images you select to reprocess at once, the longer it will take. We find it more efficient to reprocess images on an as-needed basis than to try to do all our older images. If we need to reprocess a lot of images, we let Aperture work on it at night or when we're away from the computer.

With digital images, there's just no excuse to show pictures with a crooked horizon. Whether you're handholding or carefully composing a shot on a tripod, it's all too easy to accidentally hold the camera at an angle. Then when anyone looks at your photos, the first thing they notice is the tilt rather than the subject you want them to see. Fortunately, it's easy to fix crooked images in Aperture.

To straighten an image, follow these steps:

Click the Straighten tool from the group of tools beneath the Viewer, as shown in Figure 6.3, or press G to use the keyboard shortcut. The cursor changes to a double triangle.

Click on the image. A yellow grid appears superimposed over your image.

Drag the cursor to rotate the image using the yellow grid as a guide to align any vertical or horizontal items. Aperture simultaneously straightens the image and crops it.

Sometimes you need to crop an image, whether to remove distracting items around the edges, to help emphasize the subject, or because you need to output the image at a specific aspect ratio that's different from the one your camera uses. Aperture enables you to crop images while maintaining the same aspect ratio your camera uses, to apply other preset crop sizes, or to create a custom crop. To crop an image, follow these steps:

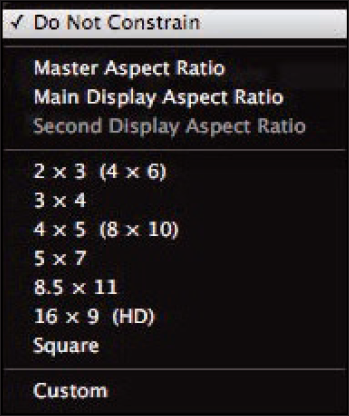

Click the Crop tool (see Figure 6.3) or press C to use the keyboard shortcut. A new dialog appears, as shown in Figure 6.4, in which you choose the aspect ratio for the crop.

Initially, the Aspect Ratio pop-up menu is set to Maintain Aspect Ratio. To use a preset ratio or to create a custom crop, click the pop-up menu and choose a preset or click Do Not Constrain. The Crop dialog displays the aspect ratio.

To toggle the height and width aspect ratios, click the double arrow that's between the height and width displays.

Select the Show Guides option to superimpose a Rule of Thirds grid while you drag out the crop. This grid can help you place the crop for the best composition following the basic Rule of Thirds principles.

Click and drag on the image to establish the crop. Click and drag in the center of the crop area to reposition the crop. Click and drag any of the rectangular handles on the edges of the crop to change the size of the crop. When you're satisfied with the results, press Return to crop the image. A Crop brick appears in the Adjustments Inspector.

You can modify the crop at any time by clicking the Crop tool again and repositioning the crop. To remove the crop entirely, deselect the Crop brick check box in the Adjustments Inspector.

Warning

The size of the cropped image appears at the bottom right of the Crop dialog. Be careful to leave enough pixels that you can still create high-quality output. If you crop too aggressively you may find that there are only enough pixels to create a very small print or to put on the Web.

Sometimes when taking pictures of people and using a flash, you may find that their eyes look red. The people aren't really possessed by the devil! Instead what happens is that the pupils of their eyes are at least partially dilated because the surroundings are a bit dark. When the camera sets off the flash, it lights up the blood vessels in their eyes, which appear red. Many cameras now incorporate a preflash to help constrict people's pupils. But if you have images of people with a red eye effect, it's easy to correct. To remove red eye, do the following:

Click the Red Eye removal tool by clicking the icon beneath the Viewer, or by going to the Adjustments pop-up menu. A new dialog appears and a Red Eye brick is added to the Adjustments Inspector.

Click on a red eye and the red eye disappears. A yellow circle with centering lines appears, as shown in Figure 6.5. Use the radius slider to adjust the size of the circle. Be sure to cover the entire pupil and possibly a little extra. You don't need to make it the exact size of the pupil but you need to err on the large side.

Move the cursor to any other red eyes and repeat.

Use the sliders in the Red Eye brick to refine the corrections. You can modify the size using the radius slider or the opacity of the correction by using the sensitivity slider.

Aperture offers a comprehensive set of tools to optimize your images that we cover individually and in depth in this section. But there are also some commonalities among all the adjustments that we cover first, such as setting the preferences for clipping, creating new versions for adjustments, working with histograms, controlling which adjustments appear in the inspector, and brushing adjustments in and out of an image.

Before we look at using the actual adjustments, we need to set some preferences that control several aspects of the adjustment tools. To do this, follow these steps:

Open the Preferences dialog by choosing Aperture

Specify the Hot and Cold area threshold settings. These settings determine what areas Aperture will show as clipped (so dark or light that there are no visible details) when you choose View

Set the Auto Adjust Black Clip and Auto Adjust White Clip settings. We prefer to set the Black Clip to 0.01 and the White clip to 0.00 rather than the default settings of 0.10. That way, if we use an auto adjustment it introduces only minimal clipping in the shadows, which is just enough to add some shadow definition and no clipping in the highlights.

Leave the option for the Clipping Overlay to appear in Color because for most images it's easy to see that way. If the image has a lot of pure red or pure blue, you may prefer to select the Monochrome option so clipped areas appear as a medium gray.

Leave the option to create new versions when making adjustments unselected. If you select it, then every time you make a new adjustment, Aperture creates a new version, which is quite cumbersome. We find it preferable to manually create new versions when we want them. Be sure that in Preferences

To create a new version from the Master, choose Photos

To create a new version from a version, choose Photos

Note

Creating versions of a master file this way requires only minimal memory space because the original pixels are not duplicated. Each version just contains a series of instructions of what adjustments to apply to that version. However, versions that are created for use with plug-ins or external editors require considerably more space because they are new master files and contain pixels. We cover plug-ins and external editors later in this chapter.

One of the advantages of working with digital files is being able to use histograms. Histograms show the distribution of the tonal values in an image and can be set up to show individual channels, a combination of the Red, Green, and Blue channels (RGB), or the luminosity information. This enables you to see factually whether an image is taking advantage of the complete tonal range or whether it's lost a lot of information in the highlights or shadows, and more. A complete discussion of histograms is beyond the scope of this book

To specify the type of histogram you want Aperture to display on the top of the Adjustments Inspector, do the following:

Select an image, and then choose the Adjustments Inspector.

Click the Action pop-up menu beneath and to the right of the histogram, as shown in Figure 6.7.

From the pop-up list, scroll to the bottom and choose the type histogram you prefer. We prefer to use an RGB histogram for the overall image histogram because it provides the most information.

Note

When making a Curves adjustment you can choose a different type histogram to appear superimposed on the curve by going to the Action pop-up menu in the Curves brick. In Levels, you can choose RGB or Luminance from the Channel pop-up menu to control the type of histogram that appears in the dialog.

No matter which type adjustment you use, they share some common features, as shown in Figure 6.8.

Disclosure triangle. Use this to expose or hide the settings for each adjustment. We normally leave the adjustments exposed but that means we have to scroll through them; hiding the controls means less scrolling. That's strictly a personal preference.

Check box. When selected, the adjustment is applied to the image. To see the image without the effect, deselect this box. It's an easy way to be sure you're heading in the right direction with your improvements, then toggle it back on again. All sliders can be continuously readjusted.

Sliders. Most adjustments contain sliders that can be directly adjusted, but double-clicking the knob resets that slider back to the default setting. In addition, many have a scrubby number field in which you can type a specific number or click and drag the cursor to quickly set the slider.

Curved arrow. Use this to reset an adjustment to the default settings.

Action pop-up menu:

Add New...adjustment. To add an additional brick of the same type, click the Action pop-up menu in the brick and choose Add New ... adjustment. This is helpful when you want to brush the adjustment in one way to parts of the image and use the same controls to make a different adjustment to affect other parts of the image.

Add to Default/Remove from Default. To add an adjustment to the default series of adjustments that appears for each image, choose Add to Default from the Action pop-up menu. Normally this would apply to adjustments that are not in the default set of adjustments but are available from the Adjustments pop-up menu, as shown in Figure 6.9. Similarly, to remove an adjustment that you don't use often, choose Remove from Default Set.

Most (but not all) adjustments have the option to be brushed in or out from the Action pop-up menu as shown earlier in Figure 6.9, while some also contain a brush icon to directly access the brush in or out of the dialog. The ability to brush the effect in or out without needing to make a separate selection is a huge addition to Aperture 3. To brush an adjustment in (or out), do the following:

Apply an adjustment. Initially it affects the entire image.

Choose Brush adjustment In or Away from the Action pop-up menu at the top right of most adjustment bricks. A new, small dialog appears, as shown in Figure 6.10. If you opt to brush the adjustment in, the brush is selected and the effect disappears from the entire image preview, whereas if you opt to brush it out, the eraser is selected and the effect remains.

Set the brush parameters in the dialog.

Choose the size of the brush. Normally, we work using a magnified view so that we can work accurately

Choose the softness of the brush. The softer the brush, the more the changes blend into the background; the harder the brush, the more discrete and obvious the edges are. Usually, we work with a soft to mostly soft brush.

Specify the strength of the adjustment. The setting you use here controls the initial strength of the change, but you can modify it after the fact in most cases by adjusting the settings in the adjustment brick. In addition you can vary the strength setting for each brushstroke to apply the effect in differing intensities.

Choose Detect Edges to have Aperture automatically limit your brushstrokes to certain areas. That way you can quickly modify one or more discrete areas of the image without having to use an external editor and make a selection. When you use Detect Edges, the size of the brush is smaller than it would be otherwise.

Choose from several other controls located in the Action pop-up menu in the upper right of the small dialog to control how the effect is applied.

Choose whether to apply the effect to the entire image, clear the effect completely, or invert which areas show the effect.

The next group of options controls whether to apply an overlay to make it easier to see where you've applied the effect.

The last group of controls limits the brush to applying the effect to just the highlights, middle tones, or shadows.

When you take advantage of the option to brush an effect in or out, be sure to zoom in and work carefully so you don't accidentally leave sloppy edges around the effect. Remember that you can apply an effect in one area and then open another adjustment of the same type, with slightly different settings, and apply that adjustment to a different part of the image by choosing Add New adjustment from the Action pop-up menu in the adjustment brick. The ability to brush adjustments in and out to create localized adjustments gives you a huge amount of control over your images without ever having to leave Aperture and without having to make difficult and time-consuming selections.

Note

Press

In this section, we cover the basics of using each adjustment including those that appear by default in the Adjustments Inspector and the additional adjustments that are available from the Adjustments pop-up menu. Of course, no image needs every adjustment. Before you begin adjusting your image, we highly recommend that you take a minute to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the image and develop a game plan for what you need to do to make the image pop. That way you won't waste time floundering, randomly trying different adjustments, and instead will select only the adjustments you need for each image.

One of the really convenient things about using Aperture to optimize your images is that every edit you make within Aperture (not a plug-in) can be modified at any time in the future. It's all nondestructive. As mentioned earlier, you can create multiple versions of an image using different adjustments or crops. These versions require only minimal additional hard drive space, and that means you can feel free to create and experiment while creating multiple renditions of an image.

Note

The order that the adjustments appear in the Adjustments Inspector is the order in which Aperture applies them to your image. You cannot rearrange the order they appear in the brick, but you can select them and work on them in any order you choose. However with some processor intensive adjustments such as the Retouch brush, you may find that your computer works better if you apply those adjustments before making other adjustments.

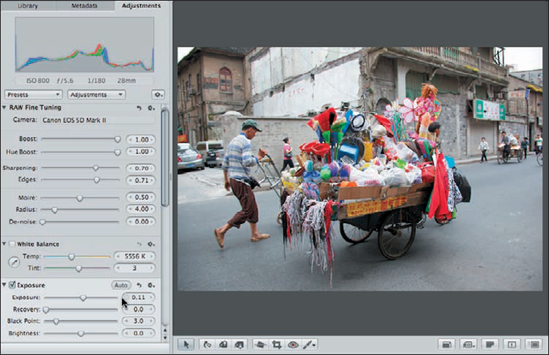

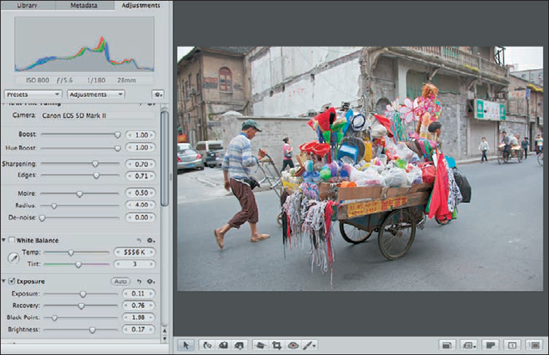

The Raw Fine Tuning brick appears automatically for all RAW files but is unavailable if the file is not a RAW file. It contains controls that let you further customize the algorithms used to decode the RAW file. Aperture uses algorithms that Apple has developed for each supported camera as well as DNG files, but your individual camera may differ from the one the engineers used and you may want to modify the settings used for specific types of shots, such as those with higher ISOs, or individual images. The available sliders are:

Boost. This slider controls the amount of overall contrast by making the lighter tonalities lighter at its default setting of 1.00 and reducing the brightness of the middle and lighter tones when the slider is moved left toward zero. In most images, the darkest tones are minimally affected at most.

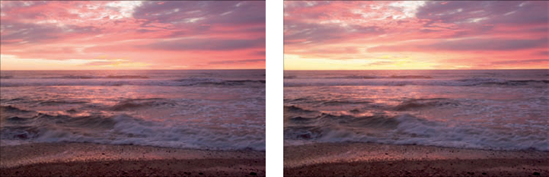

Hue Boost. This slider controls some color shifts that may appear when the Boost slider is used. At settings of 0.00, the original hues are preserved, whereas at 1.00 some color shifting is applied. The Hue Boost may make it possible to see more color differentiation and seems to work best with nature photographs. We find that settings of 1.00 often reveal additional hues in bright sunsets or highly saturated subjects such as sunsets as shown in Figure 6.11. You may need to experiment with various Boost settings as you modify the Hue Boost slider.

Sharpening. This slider controls the amount of sharpening applied to the image during the RAW decode. This is to counter the small amount of softening that occurs as digital images are captured.

Edges. This slider controls how different two pixels have to be before Aperture considers them an edge. It applies the sharpening to areas it defines as being an edge.

Note

View your image at 100 percent magnification before adjusting the Sharpening and Edges sliders. Experiment with a variety of combinations of settings but keep in mind that the Sharpening slider essentially controls the amount of sharpening to add to the edges, and the Edges slider controls where that sharpening is applied. Remember that this sharpening is not intended as output sharpening; there are other specific Adjustments for output sharpening.

Moire. This slider controls the anti-aliasing correction applied to control some high-frequency issues. In plain language, that means that it can be used to correct some digital artifacts that occasionally appear in images with certain types of linear repeating details such as window screens. If it looks like a silk moiré pattern (and thus the name) appears somewhere it shouldn't in your image, try adjusting the Moire slider. However, most of the time you won't need to touch this slider at all.

Radius. This slider is used in conjunction with the Moire slider to determine what areas of the image are considered to be high frequency and thus control where the Moire correction is applied.

De-noise. This slider controls the amount of smoothing applied to the image to reduce noise. At 0.00, no noise reduction is applied. Because the smoothing is likely to reduce any fine details in the image, we recommend against using this slider whenever possible. We prefer to apply noise reduction only where needed and use the De-noise adjustments or plug-ins for this. However, in certain images shot at high ISOs or with very long exposures, especially with older digital cameras, the De-noise slider may be helpful. As with sharpening, be sure to view the image at 100 percent magnification to accurately see the effect.

If you adjust the sliders and create a group of settings that you want to save to apply to other images shot with the same camera under similar conditions, do the following:

Click the Action pop-up menu in the top right of the brick and choose Save as Camera Default. A new dialog appears.

Assign a descriptive name for the new preset so that you easily recognize it in the future.

Click OK to save the preset and have it appear in the Camera pop-up menu at the top of the brick. When you want to use that series of settings for one or more images, select the images and choose the preset. The RAW decode for the images changes accordingly.

Many photographers leave their cameras set to auto white balance, which usually does a good, but not always perfect, job of balancing the light so that the colors in your image appear the way you expect. Some photographers use white balance presets such as daylight cloudy, shady, fluorescent, and so on, offered in their camera presets. These settings often do a good job as long as the lighting conditions don't change without your changing the preset. Still other photographers set a custom white balance setting in-camera that works perfectly...as long as the lighting remains identical to the conditions in which they created the preset. The bottom line is that no matter which approach to white balance you take in-camera, you may want to tweak the white balance settings on the computer. In Aperture 3, there are two places to adjust the white balance settings — in the White Balance brick and in the White Balance presets.

If the overall color of your image appears too cool or too warm, or is just off in some way that you can't quite identify, one way to fix it is to try the White Balance presets to see which one does the best job of balancing the colors. To use the White Balance preset, follow these steps:

Click the Presets pop-up menu and then choose White Balance. A list of six preset white balance settings appears.

Hover the cursor over a preset and a thumbnail of the image appears with that white balance setting, as shown in Figure 6.12. Being able to preview the results of each preset makes it easy to select the best one.

If the result is not perfect, continue on to the White Balance adjustment brick to fine-tune the Tint and Temperature sliders.

Whenever you want to tweak the white balance of your image, you can adjust the Temperature and Tint sliders in the White Balance adjustment brick. Use the Temp slider to warm or cool the image by dragging it toward the blue or yellow side. This is a common adjustment. Some images also benefit from adjusting the tint, making it more magenta or more green, but in most cases we find we make fewer adjustments to the tint and when we do, the adjustments are usually smaller than those we make to the Temp slider.

If you aren't sure what combination of settings the image needs, Aperture can give you some help if there's something in your image that should be neutral gray. By neutral, we mean something that should be gray, whether light gray or dark gray or somewhere in between, but pure gray without a colorcast. This might be a gray rock, a gray card, an item of clothing, a road, a bird, or whatever is in your image that should be neutral gray. If there is something in your image that should be neutral gray, take the following steps to have Aperture customize the white balance settings for the image:

Click the Eyedropper tool in the White Balance brick. The cursor changes to an eyedropper and the Loupe tool appears, as shown in Figure 6.13. As you move the cursor, the area appears magnified in the loupe to help you choose the pixels that should be neutral gray.

Click to have Aperture adjust the white balance to make those pixels neutral gray and to readjust the rest of the image accordingly. If you don't like the results, press

The Exposure brick has four sliders that enable you to adjust the overall exposure of the image as well as to recover detail in some of the lightest areas of the picture, to set the black point, and to adjust the overall brightness of the image.

Begin by setting the Exposure slider so that most of your image is exposed correctly. Before you set the other sliders, it's possible that the overall image may still be a little too bright or too dark, and in some cases there may be a small amount of highlight clipping. The idea is to get the bulk of the image correctly exposed using this slider in such a way that you can use the other sliders to refine the results and improve the exposure of the image, as shown in Figure 6.14.

Note

While adjusting the Exposure, Recovery, and Black Point sliders, hold down the

If there is some highlight clipping, use the Recovery slider. In some cases, highlight detail has been recorded by the sensor, but that isn't currently visible, as shown in Figure 6.15. This is the information that you use the Recovery slider to access. Adjusting the Recovery slider also makes some of the brightest pixels slightly darker in order to enable more highlight details to become visible.

Note

Use the Recovery slider to access highlight information that isn't currently visible but that was recorded by the sensor. Use the Highlight adjustment when you want to make the highlight details that are just barely visible darker and therefore more apparent.

Use the Black Point slider to determine which pixels will be pure black, as shown in Figure 6.16. (This is called setting the black point.)

Adjust the Brightness slider to change the overall brightness of the image, as shown in Figure 6.17. This makes the majority of the pixels lighter or darker but has less effect on the lightest and darkest pixels.

Figure 6.16. Holding down the

Figure 6.17. Use the Brightness slider to adjust the bulk of the pixels to be lighter or darker while maintaining the black point.

Note

You can also set the black point using Curves or Levels, but doing so darkens more of the pixels. Setting the black point using the Black Point slider affects less of the tonal range. Which way is better depends on the particular image. If an image just needs some true blacks for definition and pop, then use the Black Point slider. If the image feels too light and needs to be darker or denser, then set the black point in Curves or Levels.

By using the four sliders in the Exposure brick you should be able to set an acceptable exposure level in the overall image even though you may still need to use other tools to add (or reduce) contrast or to improve highlight and/or shadow detail.

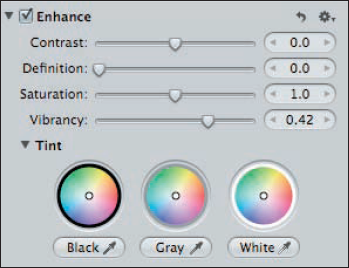

The Enhance brick contains four sliders as well as tint controls that enable you to modify aspects of the color and contrast of the image, thereby increasing the impact of many images. As we describe each control, we suggest you experiment by pulling the sliders to their extreme positions in both directions. That way you'll visually see the effect each control has and can then set the slider to the best position for the particular shot.

The first slider is the Contrast slider that enables you to increase or decrease the overall contrast within the image. Increasing the contrast this way spreads the pixels across a wider tonal range, but primarily increases the range of darker tonalities that are included. You can see the change not only in the image, as shown in Figure 6.18, but also in the histogram. Notice that the white point is only minimally modified. With images that are overly contrasty, try slightly reducing the overall image contrast.

Note

For most images, we find we rarely use the Contrast slider, preferring instead to use Levels and Curves adjustments where we can increase the contrast in particular parts of the tonal range such as the midtones.

Figure 6.18. Increasing contrast by using the Contrast slider moves the black point more than the white point but can be used to boost the contrast of overly flat images.

The next slider is the Definition slider. We use this adjustment on many of our images to increase the pop of the image. Increasing the definition increases midtone contrast as well as adding some saturation and sharpness, as shown in Figure 6.19. Although it can be tempting to use this slider aggressively, as we have done here, we suggest you use it carefully and check the results at 100 percent magnification to ensure you don't accidentally add artifacts.

Note

The Definition slider is very similar to the Clarity slider in Adobe products such as Camera Raw.

The Saturation slider increases or decreases the saturation of all the colors in the image, as shown in Figure 6.20. If you want to modify the saturation of a particular color, use the Color controls instead. Although you can convert an image to black and white by completely decreasing the saturation, we find it's better to use the Black and White Adjustment or presets that we cover later in this chapter.

Figure 6.20. Using the Saturation slider increases (or decreases) the saturation of all the colors in the image. This can result in unnatural skin tones.

The Vibrancy slider increases (or decreases) the saturation of some of the colors in the image, but is geared toward helping skin tones remain more natural looking while increasing (or decreasing) the saturation of other colors. This means that some yellow and orange tones are less affected by adjusting the Vibrancy slider, while the blues and greens will be noticeably modified, as shown in Figure 6.21. You can take advantage of the Vibrancy slider not only with photos of people, but with any photo where you want to increase or decrease the saturation of the greens and blues while having less impact on the yellows.

Figure 6.21. Using the Vibrancy slider increases (or decreases) the saturation of colors in the image while trying to protect skin tones.

Note

With some images you may want to use the Saturation and VIbrancy sliders in opposite directions to create different effects on the colors in your image. Don't hesitate to experiment in order to create just the right balance for each particular picture.

The Tint controls enable you to modify the colorcast of the highlights, midtones, and shadows separately. To access them, click the disclosure arrow to reveal three tint wheels, as shown in Figure 6.22.

Think of these controls as joysticks. To use them, click the center white circle and drag it to the desired position. To reset the wheel, double-click the white circle; it snaps back to its default setting.

Figure 6.22. The Tint wheels enable you to alter the colorcast of the highlights, midtones, and shadows separately.

Alternatively, to have Aperture help set the wheels for you, use the eyedropper beneath the wheel and click the corresponding pixels in the image. So with the Black eyedropper, click on the darkest area in the image that you want to be a neutral black. Similarly, use the White eyedropper to correct the colorcast of anything that should be white by selecting it and then clicking on anything white in the image. Use the Gray dropper to balance the colorcast in areas that should be a shade of gray without a colorcast. As you use each eyedropper you'll see the position of the center point on the Tint wheels move as well as see the color change in the image. Of course, you can still manually drag the position of the Tint wheels to suit your taste.

Although we don't use the Tint wheels often, we do find them helpful for modifying the colorcast of shadows or highlights, especially when we want to warm the highlights slightly. The Tint wheels can also be helpful if your image was shot with a mix of lighting types such as fluorescent, tungsten, and daylight.

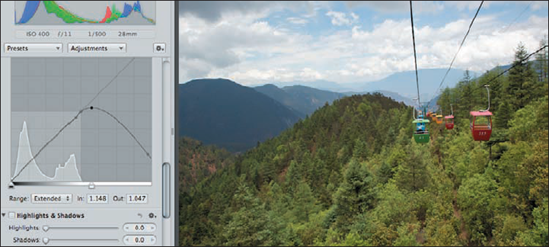

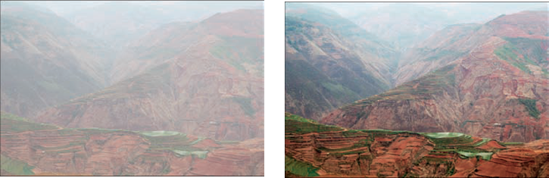

The Highlights & Shadows controls enable you to reveal more detail in the highlights and/or shadows of your image. We find the Highlights & Shadows adjustments very helpful with contrasty images where detail has been recorded in the highlights and shadows, but was initially too light or too dark to easily see, as shown in Figure 6.23.

Figure 6.23. Use the Highlights & Shadows controls to reveal more detail in the lightest and darkest areas of your image.

We recommend that for best results you use the expansion arrow to reveal the Advanced controls, as shown in Figure 6.24.

To use the Highlights & Shadows controls, do the following:

Set the Highights or Shadows slider for the amount of lightening for the shadows and/or darkening for the highlights. You may need to modify the setting after you adjust the other controls.

Set the High Tonal Width slider for the Highights and/or the Low Tonal Width slider for the Shadows to the minimum position (as far left) as possible while still creating the desired effect. The idea is to affect the least amount of the tonal range as possible while revealing the detail in the extreme dark and light parts of the image. That way you preserve more of the midtone contrast within the image and create more natural-looking results. As you decrease the tonal width, you may need to increase the amount slider.

Adjust the Radius slider to control how far out the effect extends. With many images you may leave the Radius slider at, or very close to, its default position; however, if initially the results don't look natural, try moving this slider.

Use the Color Correction slider to restore the intensity of the color in the pixels that are affected by the Highlights & Shadows adjustment. With some images you won't need to use this slider, while with others it will help maintain the saturation of color in the brightest and/or darkest areas of the image.

Use the Mid Contrast slider to try to restore the midtone contrast within the image. The wider the tonal width that you affect with the Highlights and/or Shadows sliders, the less contrast that remains for the midtones. We find that using the Mid Contrast slider seems to undo some of the effect of the Highlights & Shadows adjustment, which is why we are adamant about minimizing the tonal width whenever possible.

Note

Other ways to restore midtone contrast in the image are to use the Levels quarter tone controls or make a Curves adjustment, both of which we cover in this chapter.

Levels enables you to have finer control of the exposure of your image and has some sophisticated features not found in the Levels controls in most other software programs.

To begin, set the Channel pop-up menu to RGB. That way you see a histogram of the Red, Green, and Blue channels superimposed on the Levels controls to help you adjust the settings, and when you set Levels you'll be adjusting the Levels for all three channels simultaneously.

Note

You can set the pop-up menu to Luminosity to use Levels to adjust the overall luminosity of the image, but doing so means that you may accidentally introduce clipping in one or two channels in the highlights and/or shadows without being aware of it. That can cause you to lose some fine detail in the highlights or shadows. This is more of a risk with images containing highly saturated colors. Additionally, you can set the pop-up menu to affect a single channel at a time. Doing so you can use Levels to modify colorcasts because the color of the image is affected as you apply Levels to a channel individually, particularly as you adjust the brightness control.

To use Levels in it's most basic form, do the following:

Hold down the

Release the

Repeat Steps 1 and 2 using the triangle on the left. This time the image preview turns white as you set the black point or which pixels will appear as pure black.

Adjust the middle triangle to adjust the overall brightness of the image. Setting these three controls can greatly improve your image, as shown in Figure 6.25.

Note

Setting the black point in Levels affects a wider tonal range than by setting it using the Black Point slider in the Exposure brick.

Note

The boxes beneath each triangle show the numeric setting of each Levels control, with the default position of the left triangle being 0 and the right being 1. Don't get too caught up in the precise numeric readouts. Primarily, Levels is a visual adjustment.

Figure 6.25. Setting the white and black points and midtone brightness can make a huge difference in an image.

Aperture offers additional controls for Levels called quarter tone controls. The quarter tone controls allow you finer control over the exposure, enabling you to lighten or darken parts of the tonal distribution. To access them, click the button shown in Figure 6.26 and two additional bars appear on the Levels display. In previous versions of Aperture, these controls were a substitute for a Curves adjustment. Once you get used to using them, they're an easy way to quickly add some midtone contrast.

To use the quarter tone controls, do the following:

Click the triangle beneath the 3/4 tone controls near the highlights and move it toward the center to darken the corresponding pixels and toward the highlight end to lighten them.

Click the triangle beneath the 1/4 tone control near the shadows and move it toward the center to lighten the corresponding pixels and toward the shadow end to darken them.

To increase midtone contrast, move both quarter tone controls slightly toward the middle.

To have the quarter tone controls affect a wider or narrower range of tonalities, hold down the Option key, click and drag the associated bar to the right or left. Then adjust the triangle associated with the bar as usual.

Note

The Levels brick has two buttons to use to apply Levels automatically. The Auto button with the half–black, half-white circle uses the RGB mode to automatically set Levels in a way that will allow clipping in individual channels but will not introduce any luminosity clipping. The Auto button with the colored circle sets Levels for each channel individually. This can help correct some colorcasts. We rarely use the Auto buttons because we usually prefer not to introduce any clipping into our images.

The Color brick allows you to fine-tune the colors in your image. Use it to modify the hue and/or saturation and luminance of specific colors within your image. That way if you want a different shade of red or blue and so forth, you can make it happen.

When you first open the brick you see six color blocks and an eyedropper. You can adjust up to six colors in the Color brick. (To adjust more colors, add an additional Color adjustment by going to the Action pop-up menu in the brick and choosing Add New Color adjustment.) Although you can click on any of the color blocks and adjust those colors, in most images you'll want to adjust specific colors that are in your image.

To use the Color controls to modify specific colors in your image, do the following:

Click a color swatch. If you're going to adjust multiple colors, you can choose the first one and go in order, or you can try to choose the closest color. It won't matter which way you begin. In Figure 6.27 we chose to adjust the color of his shirt and so the blue swatch is clicked to begin. In most images, you'll want to adjust the specific colors that are in your image rather than the more generic colors that appear by default in the color swatches.

Click the eyedropper and drag it over your image to the problematic color. As you do so, a loupe appears to help you see the area in detail.

Click the problematic color to choose it. The color swatch in the Color brick updates to reflect the color you chose.

Adjust the hue, saturation, and luminance of the color as desired, as shown in Figure 6.28. If necessary, also adjust the Range slider to limit how far the effect extends from the color you selected.

Repeat as needed to adjust other colors, choosing a different color block in Step 1 each time until the image looks the way you want.

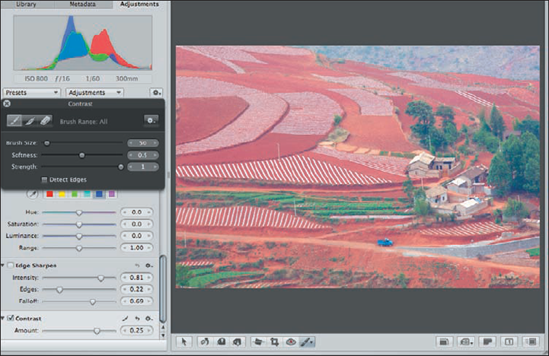

Aperture 3 has two sharpening adjustments that are available from the Adjustments pop-up menu: Sharpen and Edge Sharpen. Sharpen is available primarily for legacy reasons because it was the first sharpening adjustment that was available in Aperture 1. It exists in case you need to modify the settings you used on images that you adjusted using Aperture 1. However, you should use Edge Sharpen for all your newer images because it offers more control over the sharpening process. We use Edge Sharpen so often that we've opted to add it to the default set of adjustments that appears whenever you open the Adjustments Inspector. To add Edge Sharpen to the default set of adjustments, choose Add to Default Set from the Action pop-up menu in the Edge Sharpen brick.

To apply sharpening to an image do the following:

Click the Edge Sharpen box in the Edge Sharpen adjustment brick to apply sharpening.

Zoom in to critical areas to be able to accurately judge the effects of the sharpening settings. It's very difficult to accurately determine the amount of sharpening to apply if you don't zoom in.

Adjust the Intensity slider to control the amount of sharpening to apply.

Adjust the Edges slider if necessary. This slider determines which parts of the image are considered edges. The higher the setting, the more areas that are considered edges, and thus the more sharpening that's applied.

Tweak the Falloff slider as desired. Aperture applies the sharpening in three passes and by default it applies less sharpening on the second and third pass. Use this slider to increase or decrease the amount of sharpening applied on the second and third pass.

Note

When you sharpen a digital image you are adding contrast to the edges to give the impression of increased sharpness. You are not actually refocusing the image. Digital sharpening can't fix poor shooting techniques such as camera or subject movement while shooting or inadequate focus. It's important to always use the best camera techniques possible to create the sharpest images possible in-camera.

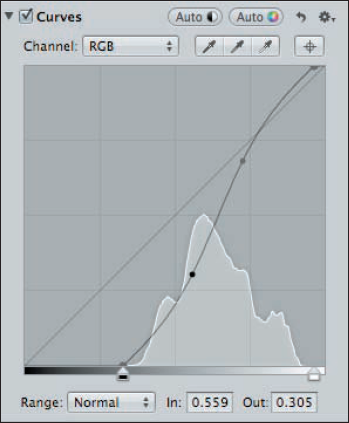

The Curves adjustment is new to Aperture 3 and in our opinion was worth the wait. Using Curves, you can modify the lightness or darkness of various areas of the image and increase or decrease the contrast in different segments of the tonal range, as well as recover highlight data. To begin, select Normal in the Range pop-up menu and RGB in the mode pop-up menu.

Initially, you see a histogram superimposed over the curve. To use curves, do the following, bearing in mind that with any particular image you may need to omit a step:

Hold down the

Hold down the

Click on the curve and drag it slightly up or down to lighten or darken pixels in that area. With curves, points closer to the tonality that you adjusted will be affected more than those farther away.

To add some midtone contrast, consider adding a point about one-fourth of the way up the curve and pulling this point slightly down. Add another point about three-fourths of the way along the curve and pull it up slightly. This increases the contrast in the middle half of the tonal range and decreases it slightly at the extreme ends. Of course, you can set these points anywhere along the curve to add contrast to as small or large a portion of the tonal range as you desire.

To remove a point that you've added, select it and then press Delete. The point disappears.

To protect a range of tones so that they are not affected by changes you make at other places along the curve, lock the curve in that area by placing three points fairly close together. That way when you adjust other points along the curve, that portion of the curve remains unaffected.

Figure 6.29 shows a Curves adjustment and Figure 6.30 compares an image before and after applying this Curves adjustment.

Figure 6.30. Using Curves is an excellent way to bring out detail in your image and correct exposure issues.

Aperture 3's Curves adjustment enables you to work more specifically with the shadows and highlights in the image. To magnify the shadow portion of the curve so that you can make finer adjustments within it, choose Shadows from the Range pop-up menu. The curve display changes, as shown in Figure 6.31 to show just the lower quarter of the tonalties, meaning the shadow portion of the image. Make any adjustments that are needed and then change back to Normal range to make adjustments elsewhere on the curve.

The Highlights range option enables you to recover information that was recorded in the file but that is not currently visible. Although most of the time you'll want to use the Recovery slider for this purpose because it's easier, if the Recovery function isn't giving you the results that you hoped for, you can use Curves in the highlight range. One of the advantages of this is that you can apply highlight recovery per channel, which may yield better results with some images. In addition, you can opt to brush the effect in or out, thereby controlling where highlights are recovered and leaving specular highlights in other areas for more natural results. To use the Extended range to recover data, do the following:

Choose Extended from the Range

pop-up menu in Curves. The curve changes so that the curve occupies only one-fourth of the dialog and shows how much information is not currently visible. Most of the time we set the Channel pop-up menu to RGB and primarily affect the luminosity of the image; however, you can also opt to work in one channel at a time by choosing the individual channel and alter the color of the image.

Move the White Point control over the right edge of the histogram data. Initially, this decreases the contrast in the image.

Move the point that's already on the curve up to the original line of the curve. This restores contrast to the image.

Lock down the curve to the left of that point by carefully adding three points close together to make sure that the changes you make in the extended range don't affect the rest of the image.

Grab the curve near the top corner and pull it down as far as necessary to recover the data, as shown in Figure 6.32. This will vary by image and the amount of detail that needs to be recovered.

Many images take on new life when converted into monochromatic images. Although you may like a particular image in color, you may be surprised to see how effective it is in black and white. Rather than simply desaturating an image, use Aperture's Black & White adjustment or Black & White presets for more control over the final result. To convert an image into black and white using the Black & White adjustment, do the following:

Choose Black & White from the Adjustments pop-up menu. A new brick appears and the image immediately becomes monochromatic.

Adjust the Red, Green, and Blue sliders as desired. Moving a slider to the right lightens the pixels with those tones in the original, and moving it to the left darkens them, as shown in Figure 6.33. So if you want the areas that were blue in the original image to be lighter, move the Blue slider to the right. If you want them to be darker, move it toward the left.

The Color Monochrome brick can be used with or without the Black & White adjustment. To use it, do the following:

Choose Color Monochrome from the Adjustments pop-up menu. A Color Monochrome brick appears. By default, the monochrome choice is set to a sepia tone.

Adjust the Intensity slider to control the strength of the sepia effect.

Click the arrow to the right of the sepia color swatch if you want to choose a different color for the color monochromatic effect. A new color palate appears. As you hover the cursor over the colors in the color palate, the image preview updates to reflect the color monochrome using that particular color.

To specifically add a sepia effect, choose the Sepia adjustment from the Adjustments pop-up menu. A small brick appears containing an Intensity slider that you use to control the intensity of the sepia effect. We prefer the Color Monochrome option because it offers more control over the final effect, but the Sepia adjustment is faster if you like the tone of it.

The Vignette and Devignette tools are separate controls available from the Adjustments pop-up menu. Although they seem to be opposite ends of the same spectrum, they're separate adjustments because Aperture applies them at different stages of the adjustment process. You can apply them whenever you want, but you can see from their location in the series of adjustment bricks that Aperture applies devignetting early on, whereas vignetting is added near the end when the final image is output.

Vignettes can be helpful to help guide your viewers' eyes toward your subject and away from any distractions near the edges of your image, as shown in Figure 6.34. Ansel Adams was a master of vignetting in the traditional darkroom.

Figure 6.34. Adding a vignette can improve an image by helping guide your viewers' eyes to the main subject.

To apply a vignette in Aperture, follow these steps:

Choose the Vignette option from the Adjustments pop-up menu. A new brick appears.

Choose either Gamma or Exposure from the Type pop-up menu. Gamma will yield a stronger overall result whereas Exposure will be more subtle.

Set the desired intensity of the vignette. We often begin by setting the Intensity to the maximum so we can easily see the effect and then back it off to a pleasing level. That helps us to set the Radius slider as well.

Set the Radius slider to determine how far the effect should extend into the image.

Devignetting is helpful to reduce any darkening around the corners or edges of an image that can occur with some lenses that were originally designed for film cameras rather than digital, or with some wide-angle lenses with lens shades or filters. Usually this type of accidental vignetting is not flattering to the image. To reduce vignetting, follow these steps:

Choose Devignette from the Adjustments pop-up menu. A new brick appears.

Set the Intensity slider to determine how much lighter to make the corners.

Set the Radius slider to determine how far into the image the effect should extend. Sometimes you'll need to readjust the Intensity slider as you adjust the Radius slider to achieve a good balance.

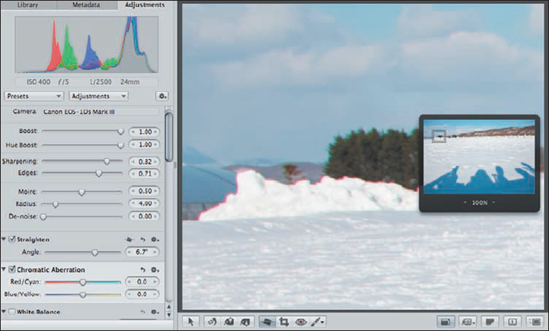

Chromatic aberration appears when the Red, Green, and Blue channels do not focus on precisely the same spot. The result is a colored halo edge along high-contrast edges in the image, as shown in Figure 6.35, particularly near the edges of the image, although it can appear anywhere in the image.

Figure 6.35. Zoom in to 100 percent magnification or greater to check for chromatic aberration on high contrast edges.

To remove chromatic aberration, do the following:

Choose Chromatic Aberration from the Adjustments pop-up menu. A new brick appears.

Increase the image magnification to see the chromatic aberration clearly.

Adjust the Red/Cyan and/or Blue/Yellow sliders to remove the colored edge, as shown in Figure 6.36.

Aperture offers a Noise Reduction adjustment that primarily reduces chromatic noise (magenta, green, and blue blobs that appear in areas that should be smooth colors). The adjustment contains two controls: a Radius slider to control how far out the effect extends and an Edge Detail slider that controls how much edge detail to retain. The higher the Edge Detail setting the less noise reduction that's applied.

We find this adjustment can be helpful with some images, particularly when brushed in, but with images that have major noise issues, we tend to prefer third-party noise-reduction plug-ins that offer more controls.

Quick Brushes are very similar to the brushes you use when you brush an adjustment in or out. The main difference is that Aperture has additional adjustments that are only available as Quick Brush adjustments. These adjustments are designed to be brushed in or out but not necessarily applied to the entire image. In this section, we describe using the Quick Brushes, including the Retouch tool and the other Quick Brushes.

Without a doubt, the Quick Brush that we use the most frequently is Retouch in order to remove dust spots due to dirt on the sensor. We also use the Retouch Quick Brush to remove other distractions. To use Retouch, follow these steps:

We recommend zooming in to 100 percent magnification when removing dust spots. Otherwise it's quite possible that you'll miss some of the smaller spots and then be embarrassed when they suddenly are more visible when you output the image at a larger size. Begin in one corner and then move in a uniform way across the image and then down, making sure not to miss any areas.

When you encounter a dust spot or streak, press X to access the Retouch tool or click the Brushes icon beneath the Viewer to the left, as shown in Figure 6.37 and choose Retouch. A small dialog appears.

Select Repair or Clone. In Clone mode, Aperture makes an exact copy of the good pixels and places it over the area you want to hide. At times this is exactly what you need, but you have to be careful not to create obvious repetitions of areas because that will broadcast the fact that you cloned something out. In the Repair mode, Aperture copies the texture from good pixels but blends the color with the color in the problematic area. Often this leads to more subtle results, but which mode is better will depend on the area of the image that you're fixing, how detailed the area is, and whether the detail in the surrounding areas is similar or totally different. There are no hard and fast rules to follow as to which mode to use, and the best advice we can offer is that if the surrounding area is fairly similar in detail, then begin by trying Repair mode. If you're removing a dust spot from a highly detailed area of an image where the nearby detail is of something else, then you may be better off with Clone mode and work at a very high magnification and with a tiny brush.

Choose the Radius of the brush. Normally, you want a brush that's fairly small because you can click and drag the brush to cover an area. You don't need to use a huge brush and cover large spots in a single click.

Set the Softness of the brush. The softer the brush, the more gradually the effect is feathered in, whereas the less soft, or harder the brush, the more discrete the edges of the clone or repair. In highly detailed areas, you may need a harder brush while when retouching areas of low detail such as sky or water or other backgrounds, a very soft brush may be better.

Set the Opacity of the brush. To cover an area completely, set the opacity to 100 percent, but if you need to blend a retouched area to help it look more natural and to hide any obvious cloning and repetition of patterns, you can retouch using a series of repairs and/or clones at partial opacities.

When using Repair mode you have the option to have Aperture automatically choose the source. We often begin by choosing this option, but if the results are unexpected and we discover that Aperture is using a source that doesn't work the way we have in mind, we leave that option unselected. In that case, as well as when using the Clone mode, hold down the Option key and click on the source pixels to load the brush with pixels.

In Repair mode there is also the option to have Aperture automatically Detect Edges. We find this option extremely helpful.

When you've set all the parameters for the Retouch tool, click and drag to cover the area. The direction that you drag the brush when using the Repair mode can make a difference in how well it works. If you aren't pleased with the initial results, try increasing or decreasing the radius slightly and/or dragging in a different direction. Often that will fix the problem.

After you use the Retouch tool, a new brick appears in the Adjustments Inspector. You can delete your retouches sequentially by clicking the Delete button in the brick, but you can't skip over several retouches and delete just one that was several steps back.

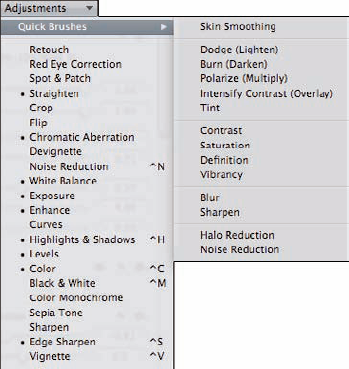

All the other Quick Brushes share a common control dialog and can be accessed either by choosing Quick Brushes from the Adjustments pop-up menu in the Adjustments Inspector and then choosing the specific Quick Brush, as shown in Figure 6.38, or by clicking the Quick Brush icon under the Viewer.

Once you choose a specific Quick Brush other than Retouch, the dialog shown in Figure 6.39 appears. Although compact, there are a lot of important options and controls packed into this dialog.

Figure 6.38. Access most of the Quick Brushes from the Adjustments pop-up menu in the Adjustments Inspector.

At the top are three choices: a brush to brush in the effect, a feather to use to help smooth the edges of the areas you brush, and an eraser to remove the effect. The feather and eraser are actually special types of brushes. All three brushes are controlled by the options in the rest of the dialog as follows:

Brush Size slider controls the size of the brush. To increase or decrease the brush size, adjust the slider accordingly or drag two fingers up or down on a multigesture trackpad.

Softness slider determines how discrete or feathered the edges of the brush are. The softer the brush, the more the effect will blend in gradually with areas that you haven't modified, whereas the less soft or harder the edges, the more abrupt the transition is. While often a soft brush is most helpful, there are times when you need the change to begin and end more abruptly, and in those cases you'll need to set this slider for a harder brush.

Strength slider determines how strongly the affect is applied. Because you can reduce the strength of most of the Quick Brushes in the associated brick in the Adjustments Inspector after the fact, you could opt to apply the effect at full strength. However, if you start to brush in the effect and it's clearly too strong, it makes sense to reduce the strength of the brush initially. Keep in mind that you can set the strength at one setting for one stroke and at a different setting for the next stroke. That way you can work precisely and get exactly the results that best suit your image.

Detect Edges causes Aperture to automatically constrain your brushstrokes to areas similar to where you initially begin the brushstroke. That way the effect doesn't accidentally seep into adjacent areas of the image. We use this option a lot and find it helps us to work more efficiently.

Use the Action pop-up menu in the upper right of the dialog to access additional controls including the options to see the brushstrokes. This is helpful when you make subtle adjustments that are difficult to see on the image. Taking the time to use the overlays, as shown in Figure 6.40, means you won't accidentally forget to include an area. Which overlay you use depends in part on personal preference and on the effect you're using.

Having the ability to limit the effect to the highlights, midtones, or shadows gives you a great deal more control over the effect. Although often you may opt to use the Quick Brushes set to All, keeping in mind the option to limit the effect to a specific tonal range enables you to have greater control over the various effects.

There is also the option to apply the effect to the entire image, whether you want it to apply to the whole image or use that as your starting place and then use the Eraser to remove it from a few areas. In cases where you want the effect to apply to the bulk of the image, it's a lot easier to begin that way rather than having to brush it in nearly everywhere.

There are a variety of Quick Brush effects. Use them as follows:

Use Skin Smoothing to reduce skin imperfections such as wrinkles and large pores. The blur effect is somewhat subtle even when applied at full strength. Using skin smoothing on portraits can make you popular with your subjects as you make their skin look even better!

Note

When using Skin Smoothing, remember to leave areas such as eyes, nostrils, mouth, teeth, hair, and earrings untouched. That way the image appears sharp, yet the skin appears smooth(er).

Use the Dodge Quick Brush to lighten areas and the Burn Quick Brush to darken areas, as shown in Figure 6.41. We find it best to work at a reduced strength and then repeat the strokes using a higher strength setting as needed.

Use the Polarize Quick Brush to deepen colors and shadows, as shown in Figure 6.42. This uses a Multiply blend effect that is supposed to simulate using a polarizing filter; however, it does not remove glare from reflective areas. We find the results can be helpful but are not identical to what you'd expect if you were using a polarizing filter on the camera.

Use the Intensify Contrast to increase the contrast by deepening the shadows while leaving the highlights mostly untouched. This adjustment uses the Overlay blending mode to create the effect and differs from the Contrast Quick Brush in that the Contrast brush causes the highlight tones to become noticeably lighter in addition to creating deeper shadows. The difference between the two brushes is shown in Figures 6.43 and 6.44, where both types of contrast have been applied to the entire image. If you don't want to risk blowing out any highlight values, choose the Intensify Contrast Quick Brush, whereas if you want darker areas to become darker and lighter areas to become lighter, choose the Contrast Quick Brush.

Use the Saturation or Vibrancy Quick Brushes to intensity the saturation or vibrancy in certain parts of your image. Using the Saturation or Vibrancy brushes on your subject can help subtly guide the viewer's eye to your subject matter, as shown in Figure 6.45. By using the Quick Brush, you can brush in these effects separately from the other Enhance brick adjustments.

Use the Definition Quick Brush to brush in the Definition adjustment effects. The Definition adjustment is the same as what's available in the Adjustments Inspector, but by using the Quick Brush you can brush the Definition in separately from the other Enhance brick adjustments. That way you can add midtone contrast, some saturation, and sharpness just where you want it in the image to help encourage the viewer's eyes to go there.

Use the Blur Quick Brush to blur any areas as desired. You might try blurring the background to help draw attention to the foreground in your image.

Use the Sharpen Quick Brush to apply a basic sharpening effect to localized areas of the image. We suggest you use this option sparingly because you have less control over the sharpening parameters this way than if you use the Edge Sharpen adjustment.

Use the Halo Reduction Quick Brush to remove any halos such as purple fringing that may occur with certain lenses. The halo reduction is slightly different from the Chromatic Aberration adjustment and is not necessary with most lenses. However, if you check your image at an increased magnification of 100 percent or more and discover purple fringing, this Quick Brush can be invaluable.

Use the Noise Reduction Quick Brush to remove noise from specific areas of the image.

The new adjustment presets in Aperture 3 are major timesavers, as we've already mentioned with the white balance presets. There are a series of presets that Apple includes by default, and additionally you can create your own presets that contain a combination of various adjustments. In addition, you can add presets that you download from other sites. All presets can be applied to your images as they're being imported, or you can apply them to one or more images as you edit the images in Aperture. Using presets is a quick and efficient way to optimize images or at least get the adjustments close to where they need to be. After you apply a preset, you can always tweak the individual adjustment settings for any particular image.

To use the presets that come with Aperture 3, open the Adjustments Inspector and choose the Presets pop-up menu. As shown in Figure 6.46, you see a menu of the types of presets that are available. As you hover over the individual presets within each category, you see a preview of the image with the preset applied. Those previews are huge timesavers because you instantly see whether a preset is helpful.

Figure 6.46. Hover the cursor over any of the presets and a preview appears showing how the image will look if you apply that preset.

The presets are divided into groups. The first group is called Quick Fixes and primarily adjusts the exposure of the image. We've been pleasantly surprised that in many cases Auto Enhance does a good job of getting an image close to the way we want to see it. Unfortunately, it sometimes introduces clipping into one or more channels, so we often modify the white and black point Levels settings it creates after applying it. Nonetheless, as shown in Figure 6.46, Auto Enhance can provide a great starting place, particularly with low-contrast images, and helps when you initially view your images.

You can apply additional presets by selecting them. The image preview will update indicating when they've been applied. For example, we might use Auto Enhance and then opt to brighten the Shadows to see more shadow detail, and then perhaps use one of the White Balance presets to correct the colorcast of the image. With any of the presets, you can tweak the settings in the appropriate Adjustment brick.

Note

To remove an earlier preset and apply a new one to an image, hold down the Option key while choosing the new preset. That way the new preset will be applied to the image instead of the earlier preset, rather than in addition to it.

The Color presets offer a variety of trendy effects you can apply. Seeing the previews is a huge help because it makes it very obvious when something is not a good choice.

As we discussed earlier, the White Balance presets offer access to the traditional white balance settings such as sunny, cloudy, shady, and so on, that are commonly used in cameras but that have been missing in earlier versions of Aperture.

The Black & White presets offer not only an additional method of converting the image to black and white, but a variety of presets that simulate the presence of various types of filters and infrared. If you want to convert your image to a monochrome, we highly recommend you check out the Black & White presets, at least as starting places.

If you have downloaded presets, such as the series of graduated neutral density filter effects for the Canon 5DMKII that we downloaded from www.maccreate.com, they also appear in the list of presets. The image preview updates to show the effect of each downloaded preset as well.

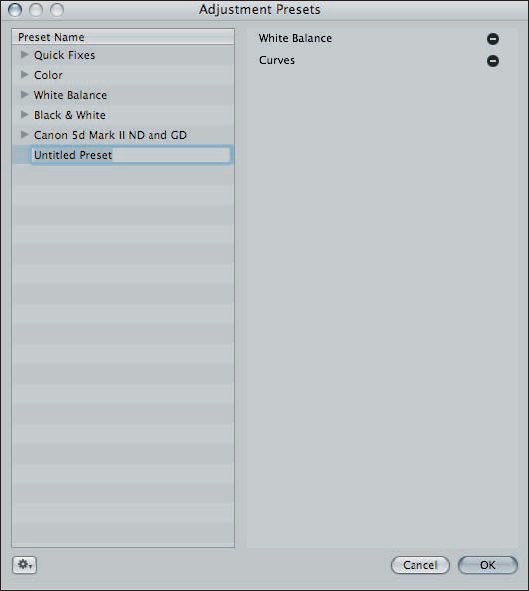

As helpful as all the default presets are, many people find the ability to create and apply custom presets even more useful. To create a custom preset, do the following:

Open an image and make one or more adjustments to the image.

From the Presets pop-up menu, choose Save as preset. A new dialog appears, as shown in Figure 6.47.

In the new dialog, assign the preset a name that is easily recognizable.

In the right section of the dialog, remove any adjustments that you don't want to include in the preset. For example, if you've modified the white balance in your image and applied a small S curve but only want to save the S curve as a preset, you'd select the White Balance adjustment in the right-hand column and click the minus icon (–) to remove it. Only the Curve adjustment remains.

Click OK to save the new preset. The new preset appears in the Preset pop-up menu and can be applied to images upon import or within Aperture.

Note

To apply a series of adjustments to multiple images, you can use the Lift and Stamp tool that we cover in Chapter 4.

As full featured as Aperture is, there are still times when you want to open your images in an external editor such as Photoshop. We primarily do this when we want to create composite images. To use an external editor you first need to specify the editor in Preferences. To set Preferences for your external editor, do the following:

Choose Aperture

Click the Choose button to set the External Editor space to your external editor such as Photoshop CS5, Elements, and so on.

Set the External Editor Color Space to use. We use Adobe RGB 1998 because it's the color space we tend to use within Photoshop.

Close Preferences.

After you establish the external editor, it's very easy to use it. To edit an image in an external editor such as Photoshop, after you've completed setting the Preferences, do the following:

Select the image or images you want to open in the external editor.

Choose Photos

When you complete the adjustments in the external editor, choose File

Warning

You must do a Save in the external editor, not a Save As. If you do a Save As, the file is stored outside the Aperture library and the image does not update in Aperture.

Over the past few years numerous third-party editing programs have been developed that enhance the optimizing options that are available within Aperture itself. There are plug-ins for sophisticated noise reduction, advanced sharpening, converting to black and white, creating HDR (high dynamic range) images from several exposures or HDR Toning from a single image, adding creative effects, adding creative borders, and so forth. Apple has a list of the various plug-ins at www.apple.com/aperture/resources/plugins.html#editing. We often use the plug-ins from Nik software, particularly Silver Efex Pro for converting to black and white and Color Efex Pro for creative effects; Dfine for Noise Reduction; Photomatix for HDR imagery; and some of the Topaz plug-ins. Many of these programs offer free trials so you can see the effects for yourself and decide which ones are the most helpful for you.

Note

We're able to offer our readers discounts on all Nik software programs. Use the promo code EANON, and on Photomatix, use the promo code EllenAnon.

Once you download the plug-ins and install them, they automatically go into the right place. You may need to relaunch Aperture to see them, and if the plug-ins have not been updated for use with a 64-bit program, you may see a message that says they only work with 32-bit programs. Follow the prompts that appear to reopen Aperture in 32-bit mode.

To use a third party plug-in that you've installed, do the following:

Choose the image and then go to Photos

Choose the plug-in you want to use. Aperture creates a new version of the file complete with all the pixel information as well as any adjustments you've added in Aperture. That version of the file opens in a new dialog for the plug-in as shown in Figure 6.48 where we used Silver Efex Pro.

Use the plug-in to make the desired changes and then click OK. The file is saved into the Aperture library and visible with your other images. You can continue to modify it in Aperture if necessary.

Figure 6.48. Plug-ins open their own interface. When you're happy with the settings, click OK or Save (depending on the plug-in).

Warning

Even if you make no additional changes to the file in Aperture, you can't reopen the file in an external plug-in and edit the settings you used. Once you click OK or Save, those changes are saved into the file.