Planning for Risk

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

• Define risk, risk management, residual and secondary risk, business and insurance risk, opportunity and threat, and the steps in a risk management process.

• Apply the concept of risk tolerance to both level of risk and category of risk.

• Conduct a risk identification process using document analysis, interviews, assumption analysis, and other techniques.

• Cite the fundamental formula of risk management (R=PxI), and apply it using decision tree analysis, risk buckets, and filtering.

• Develop risk response solutions using eight different techniques.

Estimated timing for this chapter:

| Reading | 50 minutes |

| Exercises | 1 hour 15 minutes |

| Review Questions | 10 minutes |

| Total Time | 2 hours 15 minutes |

RISK AND PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Because projects are temporary and unique, risks are an inherent part of project management. A risk differs from a problem in terms of verb tense: risks are future tense; problems are present tense. Every risk in your project will eventually go away—some by not happening at all, and others by turning into problems.

Risk management is the process of identifying, evaluating, and controlling project risks. Risks include threats (negative risk events) and opportunities (positive risk events). While threat avoidance and threat management normally occupy the majority of a project manager’s focus, it’s worthwhile to spend some time on opportunities as well. Can work done for one project benefit other projects? Has someone else already solved the problem you’re attacking, and can you use what they did rather than invent your own solution? Are there ways to do the job much faster, much cheaper, or much better?

Because not everything is ever under your complete control, risk is an unavoidable aspect of project management. The discipline of risk management doesn’t pretend that it can provide you with an absolute security blanket. Uncertainty and probability can be tamed to some extent, but never completely caged. Sometimes nasty surprises show up regardless of how much you plan, so problem-solving is also important. Still, the most important thing you can do in the face of most difficulties is to follow the Boy Scout motto: be prepared. That’s the purpose and function of risk management planning.

RISK MANAGEMENT PROCESSES

Risk management can be considered as a process of questioning your project. There are five processes in risk management, each of which explores a different set of questions, shown in Exhibit 8–1.

ISSUES AND CONCEPTS IN RISK MANAGEMENT

Risk management is a huge topic, with implications far beyond the sphere of project management. Classical risk management is primarily a statistical discipline, but project risk management focuses on uncertainty: your projects are temporary and unique, so the chance of certain risks happening is essentially unknown.

Triple Constraints Issues

A risk is not merely an uncertain event. It has a specific type of impact on your project: it impacts the Triple Constraints. The three kinds of risks are those that (1) threaten to delay your project (Time risk), (2) threaten to increase your use of money and other resources (Cost risk), or (3) threaten to degrade the quality or functionality of the deliverables (Performance risk). Your project can, of course, hit more than one of the three risks simultaneously. If the risk you’re considering won’t do any of those things, it’s not a risk—it’s merely an event.

The potential seriousness of a risk, then, is influenced based on which Triple Constraint(s) it affects. If a risk threatens your driver, it’s far more serious than if the risk threatens your weak constraint. So, the Triple Constraints model suggest a risk response strategy: exploit the weak constraint. If cost is the weak constraint, your first thought for many risks should be, “Can spending money fix this?” If it’s time, “Can letting the project finish slip fix this?” And if it’s performance, “What can I drop or modify to fix this?”

xhibit 8-1

Risk Management Processes

1. Risk management planning

a) How will you approach risk management on this project?

b) What tools will you use?

c) How much effort is warranted, based on the overall risk level and value of the project?

2. Risk identification

a) What are the potential threats and opportunities on this project?

b) What do you know about the likelihood of their happening?

c) What would be the effect on the project if they do happen?

d) Are there obvious steps you should take in response to these identified risks?

3. Risk analysis

a) How serious is each risk, both in absolute and relative terms?

b) What do you know about each risk?

c) What factors make you think a given risk is more or less likely, or more or less harmful?

d) Are there hard data available?

e) What has history shown?

f) Is this risk within the project scope or span of control?

g) If the risk is not within scope, to what extent can you reach and influence the risk or problem owner?

4. Risk response planning

a) Should you act on this risk or simply accept it?

b) Should you modify the plan in light of the risks you have judged serious, and if so, how?

c) Are there multiple potential responses, and what are the pros and cons of each?

d) Will your proposed solution create possible unwanted side effects, and if so, can those be managed as well?

e) Will your proposed solution address all of the risk, or will there still be a residual level of risk after the proposed solution is applied?

f) Does the residual level of risk need further action, or should you accept it?

g) Do you need a reserve or contingency to manage unforeseeable and residual risk, and if so, how much?

h) What will you do if surprises exceed the available contingency?

5. Risk monitoring and control

a) What risks are on the horizon?

b) What action steps do you need to be taking right now?

c) Has your knowledge or understanding of a given risk changed?

Business Risk vs. Insurance Risk

Another way to divide risks is between business risks and insurance (or pure) risks. We mostly think in terms of pure risk: a situation that, if it happens, will result in a loss. If you’re running a construction project, there’s the chance that a worker will be injured, or that a wall will collapse. Because the outcome of such events is only negative, you want to avoid the risk if feasible. Pure risk is sometimes called insurance risk, because one common strategy to deal with pure risk (the possibility of injury, for example) is to buy insurance to cover it.

Business risks are different: they have the opportunity for gain as well as for loss. A stock market investment is an example of a business risk. The value of your investment might go up or it might go down. You might think of risks as generally something to avoid, but business risks are sometimes actively chosen because they have upside potential.

You’ll need to distinguish between these two types of risk in developing your strategy.

Opportunity and Threat

The general term “risk” refers to any uncertain event that can affect your project; in discussing business risk we’ve established that some risk outcomes can be good. Risk, therefore, can be subdivided into threat (negative risk) and opportunity (positive risk). As a result, risk management includes maximizing positive outcomes as well as minimizing negative ones. If you’re managing a project that has business risk, you know there are opportunities for gain and for loss. If you can minimize either the chance of loss or the amount of loss, that’s good for the project. Similarly, it’s worth thinking how you could maximize the chance for gain or the amount of gain.

Whereas insurance risk is always negative, there also exists the possibility of good luck and positive opportunity on your project. Too often we don’t take the time to walk through our project plan and ask ourselves, “Could we get some good luck on this task, and if so, how?” You might be surprised.

Murphy’s Law notwithstanding, you might expect random events to distribute themselves more or less evenly between good luck and bad luck, but that’s not our operational experience. Projects seem to contain negative random events much more often than positive ones. What’s the reason?

One reason is that there is a structural difference in the way the two types of luck operate. Bad luck is automatic. If you lose, say, $100, it requires no additional effort on your part to suffer all the consequences of the loss. Good luck, on the other hand, normally requires a deliberate effort on your part to gain its value. If there’s $100 lying on the street, you might not notice it’s there. If you do notice, you’re under no actual obligation to pick it up. You might suspect that it’s a trick of some sort. It might be raining. You might be in a hurry. And if you do pick up the $100, you’re under no obligation to spend it wisely. You only get the benefit of the $100 as a result of deliberate, conscious action.

That has implications for project management as well. Ignoring the opportunities good luck may provide is wasteful. When analyzing risks, take a little time to consider the upside, too.

Because projects have costs, when you choose project A, you automatically choose not to do other projects with the same resources. This is known as opportunity cost, the cost of the path not taken.

Residual and Secondary Risk

A potential solution for a risk may reduce its likelihood and its impact, yet not eliminate the risk altogether. The leftover risk after you have implemented any potential solutions is known as residual risk. If you take no action on a given risk (risk acceptance), the entire risk becomes residual. (This is, incidentally, also the case if you don’t think of a risk in the first place.)

A secondary risk, on the other hand, is a brand-new risk created by your proposed solution to the original risk: if you decide to raze the old structure with dynamite, you now have a safety risk that someone could be hurt by the dynamite, whereas if you decided to use a wrecking ball, there would be no danger from the dynamite —though now you’d have safety issues with the wrecking ball. The presence of secondary risk doesn’t mean you shouldn’t use a solution. Dynamite (and wrecking balls) are used every day and injuries are uncommon. The reason is, of course, that professionals who use potentially dangerous technology normally also have methodical safety procedures they follow.

Degree and Area of Risk Tolerance

Imagine that you’re offered a stock market investment. Invest $5,000, and within six months, you will either receive $50,000 (70 percent chance) or lose the $5,000 (30 percent chance). Interested? Assuming the facts check out (and we’ll assume they do for the purpose of this example), it looks like a pretty good deal.

The expected value of this transaction is (0.7 × $50,000) + (0.3 × – $5,000) = $35,000 + (-$1,500) = $33,500. In other words, if you made this investment over and over again, winning and losing according to the percentages, you would earn an average of $33,500 per transaction.

Does this sound like a no-brainer? In surveys, most people will turn this offer down. It could be because they don’t know how to do the math. It could be because any deal that looks that good generates deep suspicion. It could also be because of an emotional reaction to any sort of financial risk. But there are rational reasons someone might turn down the deal as well. If you’re an experienced investor and you’ve got $5,000 in your portfolio looking for a higher-risk/higher-gain investment, then you’d probably jump at this offer (after, of course, due diligence to make sure it is what it’s represented to be). But imagine instead that the $5,000 you’d have to put up is the mortgage and family food budget for next month. Even though that $50,000 looks very attractive, you can’t take the risk because you can’t afford the loss.

Risk tolerance is both a matter of degree and of area. For example, the same person who passes up the $5,000 investment might participate in a sport or athletic activity that carries a risk of injury or death. Another person might be willing to take on substantial financial risk, yet be extremely reluctant to attempt something physically risky. Exhibit 8-2 lists some common areas of the project that are affected by risk. Many additional areas are possible candidates as well.

Tolerance for risk is partly a matter of style and emotional preference and partly determined by your circumstances and the effect of gains and losses. Though there’s nothing inappropriate about letting emotions, personal circumstances, and style preference play a role, you should examine your own biases and tendencies to ensure that your final risk decisions really are those that are best for you.

In your role as project manager, you’ll also have to take into account your organization’s tolerance for risk, which may be greater or less than your own. Discovering organizational tolerance for risk isn’t always easy. Some managers talk a good game of taking risks and seizing opportunities. Unfortunately, when failure happens as a result of risk-taking, they look for the easiest victim to shoot for it. Other managers urge more caution, but are actually willing to accept intelligent risk-taking in a more positive spirit. Ask about risk tolerance in your organization, but also observe actual response to risk events and consequences.

xhibit 8-2

Project Risk Areas

| Type of Risk | Area of Impact |

| Business risk | Risk to the organization’s overall business interests and viability |

| Career risk | Risk to your employability and promotability |

| Financial risk | Risk of losing money |

| Legal risk | Risk of lawsuits or criminal prosecution |

| Opportunity risk | Risk that the project’s resource consumption will exclude other potentially worthwhile projects |

| Reputation risk | Risk to the organization’s (or your) public image |

| Safety risk | Risk of accidents and personal injury |

| Supply chain risk | Risk that you will be unable to obtain necessary supplies and equipment |

| Technological risk | Risk of being unable to deliver or gain the benefits from technology |

Not all the risks—even the really big risks—are necessarily obvious from a first glance at the project. It’s good practice to make the process of risk identification methodical. Follow the processes described below to help identify risks. It’s important to remember that each of these methods has biases and limitations. The more different techniques you use, the better the result will be.

Document Analysis

Even in fairly early stages of the planning work, you are already amassing a number of documents that will facilitate your risk planning. These include any contractual documents, the project charter, scope statement/statement of work, and any correspondence with the customer. Review them for areas of possible risk.

Depending on the technical area of your project, you might also have systems engineering documentation, life-cycle cost analysis, and industry-specific risk management information from which to draw. It’s worth it to do a little digging to discover these resources.

Interviews

Interview your stakeholders on risk issues. Customers, project sponsors, team members, and other affected parties can address the risk identification process from their own points of view. Although all risks affect the underlying project, different stakeholders may be more or less affected by the same risk, and as a result can focus on the ones most important to them.

In addition, interview project managers who have done similar projects, technical experts on the disciplines that are part of your project (especially those that may be outside your own areas of expertise). Also interview sponsors and other senior managers in your own organization to determine issues of risk tolerance and policy implications.

Assumptions Analysis and Brainstorming

In the preparation of your project charter, you identified a list of constraints and assumptions. The assumptions—those that you weren’t able to resolve into facts—also become risks for your consideration.

Part of your risk meeting work should be brainstorming about possible risks. This is a good way to identify global project risks. Like with all brainstorming, accept all suggestions uncritically and analyze them only after the brainstorming period has passed.

The stages of your planning process also have risk implications. Some risks are global—they affect the entire project, or can happen at any time. Others are specific—they appear within a specific task or activity. As a result, analyze your WBS for risk. In each task, what could go wrong? How would it affect the project?

Network diagramming and the scheduling process have risk implications as well. When you make strategic choices about how to set up your network diagram, you will find that the different options have different consequences.

Risks involving tasks along the Critical Path are made more serious because any delay in one of those tasks immediately delays your project completion. Risks on tasks involving slack may be at least partially mitigated because a certain amount of delay has no project deadline consequences.

Exercise 8-1

Risk Identification

Using the WBS you prepared in Exercise 4-2 (and subsequently developed in other exercises), identify the risks in the project.

xhibit 8-3

R = P × I

Risk = Probability that the event will occur

× Impact if the event does occur

RISK ANALYSIS

The process of risk analysis is concerned with measuring the seriousness of the risks you have identified. Not all risks rise to the threshold where a response is necessary. Sometimes it makes good business sense to accept certain project risks.

The fundamental formula in risk management is R=PxI, as described in Exhibit 8-3.

The quantified value of a risk is equal to the probability that it will occur times the impact if it does occur. This gives you a risk score or risk category that you can use to develop an appropriate and proportional response.

Let’s assume that if there’s a machining error of greater than 1/1000” in your manufacturing process, the final product will fail its quality control test. If there’s a 10 percent chance of this occurring (based on your history with machining that kind of part), and the cost of a product failure is $15,000, then the risk score is 10% × $15,000, or $1,500. If buying a new lathe that has better reliability costs $5,000, and you don’t need it for other work, then it’s probably better to accept the risk of product failure.

Of course, that’s not an absolute. There could be other consequences of product failure that you can’t easily quantify, and if so, you might choose to make the investment in a new lathe anyway. For example, you might feel that your reputation for no-fail quality is important enough to justify the extra expense.

In risk analysis, project managers apply numerous tools. Here are some of the more common.

Decision Trees

Sometimes, you have a choice between decisions that each contain risk. If you’re considering purchasing a new lathe, maybe you have two to choose from. One lathe costs $50,000 and has an error rate of 4 percent. The other lathe costs $60,000 and has an error rate of 3 percent. You make 10,000 widgets a year. Each error costs $200. Which machine should you buy?

One common tool for this kind of analysis is known as a decision tree—a tool that graphically displays the financial consequences of different choices or chance events. Exhibit 8-4 shows a decision tree analyzing the risk choice to be made in this example.

In the decision tree shown in Exhibit 8-4, the total cost of the first option is the $50,000 for the lathe plus $80,000 for the cost of errors (4% × 10,000 = 400, at $200 apiece). For the second option, it’s $60,000 for the lathe, plus $60,000 for the cost of errors (3% × 10,000 = 300, at $200). The first-year total cost for the cheaper lathe is therefore $130,000, and for the more expensive lathe is $120,000. Paying for the more expensive lathe saves you $10,000 in the first year. It’s fairly obviously the right decision. (Remember, you can consider any number of options in a decision tree, not merely two.)

xhibit 8-4

Decision Tree

Often, if the numbers are close, it’s not appropriate to make the decision based on numbers alone. For example, how accurate is the percentage failure rate in the above case? If the accuracy is ±1%, then the first branch of the decision tree is actually a range between $110,000 and $150,000 (3%–5% failure rate), and the second branch is actually between $100,000 and $140,000 (2%–4% failure rate). They overlap by $30,000. Now, your decision to purchase the more expensive machine isn’t necessarily justified on economic grounds alone. Don’t give your numbers more credence than they deserve.

In short, numbers are decision inputs, not decisions. That doesn’t mean they aren’t worthwhile; quite the contrary. They just aren’t always sufficient.

Risk Buckets

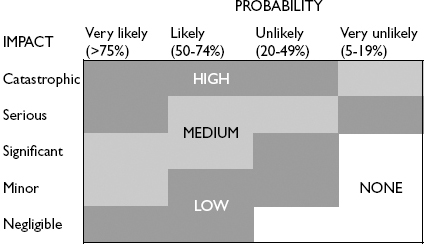

It’s often the case that you have a general idea about probability, but there’s no legitimate way for you to assign a firm number. A risk bucket is an unofficial term to describe collections of high risks, medium risks, and low risks, in cases where you’re not necessarily able to assign specific numbers to the individual risks. You can rank risks into categories by using a risk impact assessment form such as the one shown in Exhibit 8-5.

Exercise 8-2

Risk Buckets

From the information you developed in Exercise 8-1, classify each risk based on your estimate of severity of impact and likelihood of occurrence, and rate each risk as HIGH, MEDIUM, LOW, or NONE

Filtering Technique

Another technique for risk analysis is filtering, in which you use screening questions to sort risks requiring immediate action from those that can wait or safely be ignored. Filtering is particularly useful when information is scarce and hard to quantify.

xhibit 8-5

Risk Buckets

To perform a filtering analysis, the project manager asks yes/no questions about each risk to sort them into qualitative categories for further analysis. Exhibit 8-6 lists sample filtering questions, but it’s often desirable to adjust the questions to fit the circumstances of your project.

After you have filtered your risks using the diagram shown in Exhibit 8-6, all the risks will end up in one of the following categories: minor risks, unlikely risks, urgent risks, out-of-scope risks, and risks to act on. You will probably accept the majority of minor and unlikely risks. Urgent risks, of course, demand immediate attention. Out-of-scope risks may have to be routed to their proper owner (such as the customer or higher management); if any risks are not actionable, someone has to decide whether they are serious enough risks to bring the project rationale into question. Risks that require action, of course, move on to the next step.

xhibit 8-6

Filtering Questions

After applying the appropriate techniques, you should end up with a list of risks that have been quantified and prioritized. You will have to set some sort of threshold that distinguishes risks that you plan to deal with and risks you will not. You might set a dollar or score threshold, or you might look ahead to your risk response planning work and decide to drop every risk where the cost of cure is greater than the cost of the risk.

Whatever method you use, show your risk management plan to sponsors and stakeholders to get their approval. You need for your stakeholders to be aware which risks you can effectively manage, and which ones you simply must accept.

RISK RESPONSE PLANNING

Taking your prioritized list of risks, you now must come up with a potential strategy or solution for each. Depending on available resources and options, there may be a finite limit as to how much of the list you’ll be able to treat.

There are a limited number of risk response strategies, and they exist both for threat risks and opportunity risks. Exhibit 8-7 lists the various options available for risk response planning.

Exercise 8-3

Risk Response Planning

Using the risks developed and analyzed in Exercises 8-1 and 8-2, prepare a risk response plan for the risks you determined were HIGH or MEDIUM.

xhibit 8-7

Strategies for Risk Response for Threats and Opportunities

Modifying the Plan for Risk

For each risk on your action list, consider if you can modify the plan to deal with the risk. If there’s a chance that a vendor delivery will be late, you might alter the schedule for that task so that a certain amount of lateness does not pose a problem. You can add money or resources to a task, modify its position in the Network Diagram, or change some aspect of its performance criteria. You can use the techniques of avoidance, mitigation, and transfer in this way. Acceptance, of course, doesn’t modify the plan.

Sometimes, you would prefer not to incur the cost of dealing with a risk unless it’s almost certain that the risk is going to occur. Instead of renting a tent as part of the original picnic plan, you might decide to check a few days before the picnic to see what the long-range weather forecast looks like, and rent the tent then if it looks like rain. Contingency planning is a type of risk acceptance. Initially, you plan to do nothing—acceptance—unless you reach a triggering event or pass a threshold.

A contingency plan can be a strategy, or it can be a reserve—known as a contingency allowance—of extra time, money, or resources to be used in case of surprises.

RISK MONITORING AND CONTROL

Risk management doesn’t stop merely because you’ve written a plan, of course. Things change: some risks appear increasingly likely whereas some plummet in probability. New information is discovered. The amount of available knowledge changes. Surprises happen.

For these reasons, risk management continues throughout the project life cycle. In risk monitoring and control, your responsibilities include implementing the risk response plan; updating and maintaining the plan; managing residual risks, surprises, and problems; and managing any contingency allowances or reserves.

Implementing the Risk Response Plan

As with other elements of the planning process, you should end up with a written document, in the form of a table or narrative as you choose, that describes your risk management plan for the project. If you do similar projects, you can use previous risk management plans to build a template. Over time, as your understanding of risk improves, the document will become increasingly valuable to you and the organization. Identify major risk action points in your project schedule. You would most often use a milestone to do so. Schedule risk management meetings periodically through your project, probably not as often as project status meetings, but regularly. Set a standard agenda for these meetings that involves reviewing the current plan, determining whether circumstances or improved knowledge changes any of your risk response strategies, identifying risks that have decreased and increased as project results have come in, and identifying new risks that have only now become apparent.

Updating and Maintaining the Plan

Either you as the project manager, or a team member who has been designated risk manager for the project should be operationally responsible for the plan. Use version numbers for document control, and identify the list of those who need current risk information; these are likely to include team members, the customer, and the project sponsor, and may include other important stake-holders.

Keep a record of decisions and alterations made as a result of your periodic risk review meetings. Prepare an archival report on risks and surprises for the Lessons Learned file at the end of the project.

Managing Residual Risks, Surprises, and Problems

Residual risks are risks you decided to accept and the remaining part of risks you have mitigated. By definition, these should be fairly minor—unless, of course, you’ve made a mistake or some risks have turned out to be far more serious than you expected.

Serious or not, the noise-level risks on your project do require some attention. Are you seeing slippage on the critical path, budget creep, or tasks with lower quality outputs than expected? Day-to-day project adjustment is not unusual, and that becomes one more of your responsibilities as the project manager.

At the project’s end, review the residual risk issue. Were the risks indeed residual, or were some more serious than you expected? Were there triggering factors or special circumstances that you would expect again? What would you do differently given the experience you just had? Surprises and problems can crop up at any time, and don’t necessarily imply that you didn’t do a good job preparing the original plan. Indeed, it’s the rare project that doesn’t have any surprises.

Managing Contingency Allowances and Reserves

If you established a contingency allowance or reserve as part of your risk management planning, you are now responsible for managing it. Avoid making fixed commitments to people on your project team (or to individual project managers when managing multiple projects) about availability and use of contingency and reserve. Controlling the use and allocation of allowances and reserves is one of the most powerful tools you have when coping with an uncertain and risk-filled project.

Risks, unlike problems, are in the future. They are the threats (negative risks) and opportunities (positive risks) that have potential impact to your project, or that affect related areas, such as your organization, your customer, or yourself. The process of risk management planning can be broken into: risk management planning, risk identification, risk analysis, risk response planning, and risk monitoring and control. While classical risk is a statistical discipline, project management risk often involves situations in which risks are unclear, uncertain, and sometimes subjective.

Risks in project management operate within the Triple Constraints: they affect time, cost, performance, or aren’t risks. Risks can be business risk (combining threat and opportunity) or pure risk (only threat). Risk that remains after you’ve applied whatever solution or response you choose is called residual risk; new risk created by your proposed solution or response is called secondary risk. Risk tolerance is the level of risk you are willing to accept. Risk tolerance can be a level of degree (willing to risk losing $10,000 but not $100,000) or area (willing to accept financial risk, not willing to accept safety risk). The organization and customer, not just the project manager, establish risk tolerance levels. Risk identification is the process of determining what the likely risks on your project actually are. Such tools as document analysis, interviews, assumption analysis and brainstorming, and plan analysis help identify risks.

Risk analysis is the process of measuring the seriousness of different risks and gaining a better understanding of the risks. Risks are measured with the formula R = P × I: A risk is equal to its probability times the impact if it happens. When mitigating or eliminating a risk takes less than we judge the risk is worth, it’s usually a good idea to do so. When the cost of mitigation exceeds the economic value of a risk, consider if there are non-financial reasons to act. Decision trees compare the financial impact of different risks. Risk buckets enable you to group risks together by severity even if information is limited. The filtering technique screens risks through a series of questions.

Conduct risk response planning on the risks you judge serious. Strategies for responding to threats include avoidance, transfer, and mitigation; strategies for responding to opportunities include exploitation, enhancement, and sharing. Contingency planning and acceptance work for both threats and opportunities. Modify the project plan to include risk solutions when possible. Prepare contingency plans for major risks, or in case risks break through your first line of defense.

During risk monitoring and control, implement the risk response plan; update and maintain the plan; manage residual risks, surprises, and problems; and manage any contingency allowances or reserves. Do not make fixed commitments about contingency allowance or reserve; keep those decisions for yourself.

Review Questions

|

1. The risk tolerance of you or your organization is a function of: (a) how much money you are willing to risk on a specific decision. (b) whether your organization is in the private sector or public sector. (c) whether you have a risk-taking or risk-averse personality. (d) both the degree or level of risk and the area into which the risk falls. |

1. (d) |

|

2. How serious is each risk, both in absolute and relative terms? Answering this question is part of: (a) risk identification. (b) risk response planning. (c) risk analysis. (d) risk monitoring and control. |

2. (c) |

|

3. A business risk, unlike an insurable risk, has the potential for: (a) loss only. (b) either gain or loss. (c) gain only. (d) neither gain nor loss. |

3. (b) |

|

4. In risk response planning for opportunity risk, one strategy is: (a) mitigation. (b) avoidance. (c) exploitation. (d) transfer. |

4. (c) |

|

5. One strategy for managing risks involves considering the Triple Constraints factor known as: (a) the weak constraint. (b) the driver. (c) the critical path. (d) assumptions and constraints. |

5. (a) |