Chapter 2

A Dynamic View of Organizational Effectiveness

Built-to-Change Strategy:

Sustained Effectiveness Requires Continuous Change

Al Egan was born in Sioux City, Iowa, in the early 1940s and was raised as a typical middle-class midwesterner. He went to Morningside Junior College, served in the Marines, and did a tour of duty in the Korean conflict. After he completed his military service, good fortune came his way as he met and married the daughter of an entrepreneur. His new father-in-law founded a company that processed, packaged, and distributed peanut butter and snack foods. Al joined the company and steadily rose through the ranks. Eventually he became VP of operations, responsible for purchasing, manufacturing, and logistics. He was known in the vernacular of the time as a “people person” who was able to work with employees, keep the manufacturing lines operating efficiently, and acquire commodities at good prices. He lived his midwestern values by being a devoted employee who worked for the good of the company.

By the time he was forty, Al and his wife had four children and a five-bedroom house on a golf course. But Al’s life was about to hit a wall. His marriage soured, divorce ensued, and Al found himself on the outside of the family business in need of a job. This was a tough time for Al, but trading on his industry knowledge, his reputation for devotedness, and the positive working relationships he had developed, Al found a senior position in a southern California company that processed nuts and chocolates. This allowed him to expand his expertise—he could smell a block of chocolate and tell you where it was made. He thrived for almost ten years in this job. But when his company was acquired by a large multinational, the new parent summarily replaced the top management team with its own people. Al was on the street again.

At fifty years of age, Al was depressed. Although he believed he had many years of productive work left in him, there were few companies that needed his particular mix of skills.

After six months of reflection—he called it hell—Al tapped his unused GI Bill funds to go back to school. He studied accounting, but more important, he got hooked on computers and learned to use CAD-CAM software. Developing a new competency was a breakthrough. Through a temporary agency, Al found a job with an aerospace firm and turned that job into a permanent position. However, Al’s career adventures were not quite over. His organization merged with another defense contractor, and he was laid off. Fortunately, this time it was only a minor blip. He was quickly rehired because of his performance and good relationship with management. His rehiring at age sixty-three allowed him to qualify for retirement benefits.

Al retired at sixty-seven. The transitions in his life did not leave him with a particularly healthy retirement account, but he is able to live a good life. He still feels restless about not doing anything “productive,” but enjoys his grandchildren and spends time at Dodger games, the theater, and concerts.

Organizations Are Like Careers

Organizations that are built to change are a lot like today’s careers—both need to be guided by a “dynamic view” of effectiveness. Firms need to not only focus on how well they are doing today, but also to be especially concerned with how well they can respond to the changing environment. Depending on when you look at Al’s career, you would say that he was wildly, moderately, or barely successful. But only by knowing Al’s history would you have any real sense of why his effectiveness was high or low. Similarly, the media’s glib attempts to blame current leaders for poor corporate performance (or laud them for outstanding effectiveness) are misleading. The truth is much more complicated, as any careful study of organizational effectiveness will reveal.

The story of Nabisco in France is a great example of how change and time must be accounted for in assessments of an organization’s performance. Increases in before-tax income between 1970 and 1973 were followed by losses in 1974 as investments for future growth were made. The losses were unacceptable to the parent firm, and the leader of the organization was replaced by a financially oriented executive.

The new CEO squeezed costs and led a reengineering initiative. Between 1975 and 1982, income before taxes grew at a healthy rate, and the new CEO was applauded. But almost everyone inside the organization agreed that the most important reason for the improved performance was the investment that had taken place during 1973 and 1974.

The financial restructurings of the new CEO mortgaged the future by reducing new product development and throttling innovation. Not surprisingly, performance began to decline, and the once very “successful” CEO was moved out. He had failed to build an organization that fit the changing business environment.

The Built-to-Change Model

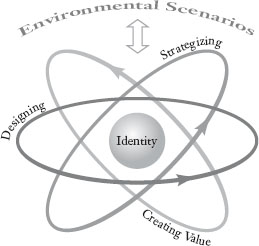

To explain the complexities of organization effectiveness over time, we have created the Built-to-Change Model. The model, depicted in Figure 2.1, consists of Environmental Scenarios and three primary organizational processes—Strategizing, Creating Value, and Designing—spinning around the organization’s Identity.

Environmental Scenarios describe a range of possible future business conditions. Most models of strategy and organization only address the “current environment,” but that is not enough when the environment is changing. Looking only at the current environment leads to building a static organization matched to the present but not to possible futures. The B2Change Model explicitly addresses ongoing environmental changes and argues that they should be the key determinants of strategy, organization design, and effectiveness.

FIGURE 2.1. The B2Change Model

Strategizing, Creating Value, and Designing are the primary contributors to organization effectiveness. These organizational processes are how an organization figures out its response to the demands of a changing environment. For example, the strategizing process includes crafting a strategic intent that describes, among other things, the breadth of the firm’s product lines, how the firm differentiates itself, and the way profit is generated.

At the center of the model is Identity. It consists of an organization’s relatively stable set of core values, behaviors, and beliefs.

The Built-to-Change Model shows the key elements that influence organizational effectiveness in motion. Strategizing, Creating Value, and Designing are each viewed as dynamic processes changing in response to or in anticipation of environmental change. The next four sections of this chapter provide an overview of the four elements of the model. Subsequent chapters will describe them in more detail.

Environmental Scenarios Drive Strategizing and Effectiveness

Al’s career spanned several different environments—from nut and candy companies to educational environments to aerospace—and each environment afforded different opportunities. As a VP he had much more upside financial potential than as a CAD/CAM operator. Like a career, an organization’s performance is determined in a major way by the current and future environments it operates in.

An organization’s external environment includes general business conditions and industry structures. Unfortunately, most traditional strategy analysis techniques are driven by assumptions about congruence and alignment that are the enemy of change. The often-used strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis, for example, encourages the firm to leverage opportunities while avoiding weaknesses and threats. This alignment among positive and negative forces is implicitly assumed to remain constant, and there is no built-in assumption of change.

B2change organizations take a very different view of the environment. First, b2change organizations look at both the current environment and the potential environments that might emerge in the future. Anticipating what the environment will be like is critical to effective change, but knowing what it will be is not possible. However, broad trends and demands can be used to generate a range of scenarios that capture some of the most likely future environments an organization will face. Electronic Arts, the game company, does just this. It spends a lot of time and resources understanding how technologies, user interests, and social trends will play out over the next three to five years and then creates scenarios that allow it to see future demands and opportunities.

Second, b2change organizations recognize that their future performance depends on how effectively they respond to the environment. The calculus of how to operate today and how to operate in the future is an obsession in b2change firms and a clear focus for the strategizing process. Ideally, what the organization offers over time will correspond to what the environment demands. We label this dynamic relationship proximity and hypothesize that organizational performance over time is a function of the extent to which an organization’s design and the demands of the environment are in proximity.

Since anticipating the exact nature of the environment is difficult, designing a b2change organization to respond quickly to unexpected environments is an important part of the designing process that will be discussed below. That said, a b2change organization spends as much time thinking about what the environment will be as it does thinking about its strategy and design.

Imagine being a provider of mobile Internet services—a business of treacherous, complex, and uncertain proportions. How should you make decisions on strategy when you are faced with declining bandwidth costs to mobile customers; converging PDA, cell phone, and notebook computer technologies; increasingly sophisticated virus programs; improved voice-based interfaces; global markets developing at different rates; and new competitors entering from a variety of industries? A b2change organization addresses these kinds of factors by generating a variety of possible scenarios.

For example, one could visualize a “Fragmented Hardware” future where the mobility market remains largely uncoordinated. Phone companies, cell phone and PDA manufacturers, and even watch companies compete to be at the center of mobile access. Competing technology standards and price wars between regional providers keep users confused and force them to choose between devices that connect to their personal, corporate, and Internet-based data only through proprietary and slow layers of communication. Customers, confused beyond tolerance, tend to buy one hard-sell approach and minimize their switching to save time. Cell phones and handheld sales stagnate in developed markets, and different technologies barely interoperate.

Another potential scenario could be the “Services Future” where the average individual business user spends $100 per month on mobility services, and the devices themselves are automatically updated by the service provider. PDAs, cell phones, and laptops are interchangeable for most business operations. Directory services that allow you to keep your phone number and email address when you change hardware proliferate. “Home” phones disappear, upgraded to wireless at no cost to the user. Phone and cable companies lose out to more nimble wireless providers.

Finally, a third scenario might be described as “Large Provider–Dominated,” where several security software providers team up with a large service provider like IBM or Oracle to provide end-to-end spam- and virus-free connectivity. “Lightweight” email, instant messaging, and data access prove compelling to users who have become fed up with spam voice mail, email, and faxes as well as constant viruses and hoaxes. Original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) partner with a preferred proprietary solution, and it becomes the must-buy add-on for connectivity. Increasing mobile usage and the preference for simple and effective renders the high-end features and integration of the more sophisticated software developers less and less valuable, thereby decreasing upgrades.

Strategizing for a b2change mobile provider would involve crafting a robust strategic intent by looking at the implications of the Fragmented Hardware, Services Future, and Large Provider–Dominated scenarios. This is very different from a SWOT analysis, which is fixated on the current environment.

The mobility business might, for example, choose between focusing on corporate customers or going for the “lowest common denominator.” A focus on corporate customers would allow the firm to gain large contracts and experience while avoiding the vagaries of individual customers. Going for the lowest common denominator would allow the firm to develop a reputation for quality first and then move up the value chain as the technology converges. In both cases, the strategic intent doesn’t presume a particular future, but it can lead to a successful path through any of the three environmental scenarios. Viewing environments as consisting of unfolding demands and using scenarios to anticipate them can help organizations identify their best strategic options.

In the 1990s, a number of companies believed there was going to be worldwide explosive growth in the market for fiber-optic and broadband communication technology. They were not wrong, but their miscalculations about the timing of the explosion and how the technology would develop nearly wiped out the industry.

Corning, for one, changed its technical core from its wide variety of traditional glass products to fiber optics. Nortel and Lucent projected dramatic growth in the sales of Internet communications equipment. When the expected growth did not materialize, the performance of these companies suffered tremendously. In a very short period of time, they went from market leaders to financial wrecks.

Other examples of environmental change abound, making the point clear: an organization has little choice but to anticipate its future environments and position itself to succeed in those environments. Organizations must deal with uncertainty by making reasoned guesses about the future—and, where possible, hedging their bets by being able to change when the environment changes.

If Nortel and Lucent had been b2change organizations, they would have viewed a range of industry scenarios—including scenarios favorable and unfavorable to them as well as scenarios projecting both slower and faster demand growth. In response, they would have crafted strategic intents that were robust in addressing the alternatives and that identified early warning signals that certain scenarios were more likely to play out than others. The early warning signals would have been used to slow the pace of the organization’s transition from older to newer technologies and services and to maintain a tighter proximity with the rate of environmental change.

Identity Is Central to Good Strategizing

Al’s career was anchored by who he was, just as organizations are anchored by who they are. Even though Al couldn’t predict the future, his midwestern values guided how he added value in his work. Al was a people person—he got hooked on Dale Carnegie courses—and he believed that success would result from the way he worked with others. Ultimately, it didn’t matter whether he was making peanut butter, candy, or aircraft drawings—it was always about people and the importance of loyalty. He never wavered from his identity. It guided him into new situations. Even in the case of the wrenching move from candy to CADCAM, he learned new skills but maintained his identity. Organizations, like people, rarely change their identities.

An organization’s identity is an overarching and relatively enduring statement of how it will achieve its long-term mission. Identity contributes to effectiveness by specifying the organization’s dominant approach to doing business. Costco’s fundamental identity is that of being a low-cost provider; Budweiser sees itself as the “king of beers”; Southwest is about low cost, freedom, and customer service; and Exxon is an energy company run by engineers.

Identity derives from the organization’s culture—what employees think they should do and what they think they will be rewarded for. It also derives from images of the organization held by competitors and customers. When employees know that their organization’s identity is understood and protected, they feel free to innovate, experiment, and push the boundaries of what is possible.

Strategizing is not just about describing a robust intent for a variety of environmental scenarios. It is also about picking an environmental path that allows the organization to remain true to its identity.

Microsoft’s enduring identity is one of persistence. The organization often produces imperfect products that are not the first to market. Over time, however, Microsoft works on improving a product’s performance until it yields a winning solution.

The importance of Microsoft’s identity to its performance was amply demonstrated during the Department of Justice’s (DOJ’s) antitrust proceedings. Despite the real threat to the organization’s identity, Microsoft never abandoned who it was. During that period, Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer said to employees, “You do what you do best. Don’t worry about DOJ; that’s our problem.” Microsoft stayed focused on the real issue of being persistent. During that period, the company’s .Net strategy was born, its mobility strategy was taking shape, MSN continued to grow, and the Xbox was being developed.

The importance of identity to performance should not be underestimated. When an organization tries to be something that betrays its identity, successful execution of an intended strategy can be thwarted by turnover, sabotage, incompetence, and reduced productivity and quality.

Many organizations have failed to perform effectively because their strategic intentions did not fit their identity. This was clearly the case when Exxon decided to go into the office equipment business in the 1970s. As one of the original “seven sisters” in the oil and gas business, Exxon (previously Standard Oil of New Jersey) grew up thinking of itself as an exploration and refining organization. Although the logic of diversifying may have been sound, entry into a different industry with completely different technologies and business models was too far beyond Exxon’s view of itself, and the effort failed. Enron’s transformation from being a gas pipeline company to being a financial trading company ended with even more disastrous results.

Strategizing Is a Pivotal Conversation

Strategizing is about describing how an organization’s products will remain proximate with an unfolding environmental path. It is a bit like a football quarterback throwing a pass. He must throw the ball to a particular point on the field with the hope that the receiver will be there when the ball comes down. There is a certain amount of faith involved—that the receiver will run the right route and won’t trip, and that the defense won’t get in the way. The closer the ball is thrown to where the receiver ends up, the greater the chance of a successful catch.

Strategizing is the process an organization uses to decide which products, services, and markets to focus on and how to compete. It results in a strategic intent that guides choices about how an organization creates value and designs itself.

Research shows that an organization’s current performance depends on the extent to which the intended strategy is proximate with the demands of the environment.1 Being in a particular business determines performance to some extent. American, United, Delta, Southwest, and Jet Blue are all in the airline transportation business. As a group, their performance over time will more likely mirror each other’s than it will the performance of companies in the consumer products industry. But their relative performance reflects the degree to which their strategy is proximate to the environment and how well they execute it.

To be effective, an organization’s strategy must address current and future environmental demands. Strategies must also reflect an understanding of the organization’s identity. When an organization’s strategic intent describes a path that is proximate to both its environment and its identity, the organization achieves critical configuration.

We chose the term critical configuration to convey the importance of specifying the relationships among environment, identity, and intent. It is critical because it represents, without question, the most important responsibility of a firm’s senior management. It is a critical configuration because it represents the set of relationships that most determines performance.

Coors achieved critical configuration in the 1980s when it chose to invest in developing aluminum cans to replace steel cans (steel tainted the beer’s taste). That intention honored its identity as a maker of beer of unsurpassed quality and recognized the opportunity to grab margins in that segment of the value chain. If Coors had decided to begin working with an inferior but cheaper type of can, that decision would have collided with the organization’s identity. Similarly, if at fifty Al had said, “I’ve had it with people; I’m just going to put my head down and crank out technical drawings,” he may have been responsive to the environment but would have been out of alignment with his identity and would not have been as effective in shifting careers.

Strategizing involves disciplined and continuous conversations about the organization’s long-term identity and strategic intent. It achieves its status as the pivotal process in the B2Change Model because it represents a dynamic response to an unfolding and mostly unknowable future. Strategizing is the primary context for making decisions about how the organization will create value and organize in the future.

When it comes to strategizing, b2change organizations need to be different from traditional firms in important ways. In traditional firms, strategic reviews are at best an annual phenomenon, and the conversation is dominated by tones of “Is there any reason to change?” B2change firms are nervous. They agree with Andy Grove that “only the paranoid survive.” They continuously examine their strategy and recognize that some things rarely change (for example, identity) and that other things may need to change relatively frequently (for example, intent, structure, and systems). They strategize continually to test whether their identity and intent are still appropriate for current and potential future environments.

B2change firms make a large investment in conversations and reflection, particularly among the senior management. The conversation is focused around the question “What’s the next thing that needs changing?” This is an explicit trade-off of some short-term efficiency for greater future effectiveness, a trade-off that makes increasing sense in a rapidly changing world.

Creating Value Through Competencies and Capabilities

The specification of strategic intent is important, but it is only part of the strategy story—implementation is the other part. No matter how brilliant a strategy is, its ultimate impact is determined by how well it is implemented. Many more strategies fail because of poor implementation than because they are conceptually flawed.

A strategic intent is just that—a description of a desired set of activities. It describes what the organization should do. To do it, an organization must identify and develop its competencies and capabilities.

Competencies

What exactly are organizational competencies? In their influential 1990 Harvard Business Review article, Gary Hamel and C. K. Prahalad defined core competencies as a combination of technology and production skills that underlie the product lines and services of an organization.2 Often parts or all of an organization’s competencies can be protected by patents and licensing agreements.

Sony’s core competency lies in the miniaturization of technology. It allows the company to make the Walkman, video cameras, notebook computers, and a host of other products. Similarly, Honda’s ability to design gasoline engines is critical to the company’s success in selling motorcycles, generators, lawn mowers, outboard motors, trucks, and automobiles. 3M’s core competency in chemical processes and materials has helped the company develop a wide range of products, from ordinary tape to exotic bonding materials for the aerospace industry.

Capabilities

If competencies are about technologies and knowledge, then what are capabilities? Capabilities are the clearly identifiable and measurable value-adding activities that describe what the organization can do.3 Usually they cannot be patented but often are hard to copy. Capabilities include the ability to create quality products, operate on a global basis, be a low-cost producer, manage knowledge, develop new products, respond quickly to the business environment, speed products to market, serve customers—and do many other things that have the potential to provide an organization with a competitive advantage.

Organizational success today frequently requires not just a single world-class organizational capability but a combination of several. It may take two or three that are exceptional and a number of others that are at least at a world-class level.

Consider 3M, which for decades has been a prime example of a company with an innovation capability. Much of the company’s success and growth over the years has had to do with their organizational capability to create, develop, and market new products, such as Scotch tape, Post-it notes, and thousands of others. The reason for 3M’s innovation capability goes far beyond the company’s technical competencies in the chemical properties of materials. It results from a variety of company-wide systems, practices, and structures that support innovation. One very specific behavior that 3M has fostered is experimentation. The company has developed a number of policies and practices that give employees time to experiment, and its reward system recognizes innovative work.

An important point about capabilities is that they require ongoing attention and maintenance. Motorola, for one, learned this the hard way. During the late 1990s, the company decreased its focus on its Six Sigma quality program and as a result fell behind the competition in several of its key businesses, including cell phones and semiconductors.

Ford Motor Company also mismanaged its quality capability. Starting in the 1970s, it invested heavily in building a quality capability and enjoyed some success. Do you remember “Quality Is Job One”? When Ford acquired Jaguar, it successfully transferred its quality knowledge to Jaguar, with impressive gains. Jaguar’s quality improved so much that during the 1980s and early 1990s it went from being just ahead of the Yugo, considered the world’s lowest-quality car, to being one of the top cars in the world in manufacturing quality.

However, while Ford was successfully transferring its quality capability to its newly acquired Jaguar subsidiary, it lost much of its quality capability in its U.S. manufacturing operations. What happened in the United States? Essentially, Ford took its eye off the ball. Like Motorola, it failed to maintain a focus on its quality capability, and as a result, quality deteriorated in its U.S. manufacturing and design facilities.

The most important capability a b2change organization can have is a change capability. And it’s the one capability that most organizations lack today. Forward-looking organizations are building and investing in their capability to manage change, but most are not. The incredible growth of the change management practices of many consulting firms is ample evidence that many organizations want but do not have this capability. Moreover, it suggests that most organizations would rather buy the capability to change than invest in it. In our opinion, this is a short-sighted, misguided, and expensive approach, given that change will be even more important in the future.

Competitive Advantage

A competency or capability is valuable to the degree that it produces revenue, reduces costs, or contributes to the real or perceived benefit of a product or service. Competencies and capabilities can be a source of competitive advantage when they are valuable, rare, difficult or costly to imitate, and leveraged. A competency or capability that is valuable but not rare is a commodity.

Some common capabilities are important because they are needed, but they do not produce a competitive advantage. For example, most organizations need to and are able to comply with safety, compensation, and other regulatory requirements. The few that cannot are at a significant disadvantage.

Traditional approaches to strategy seek a single sustainable competitive advantage. The b2change approach seeks a series of temporary advantages. It identifies those advantages through an ongoing investment in strategizing. It capitalizes on opportunities by continually building the appropriate capabilities and competencies. There is never the sense that “once we get this capability into place we will have a sustainable advantage and can relax.” Instead there is a constant focus on harvesting the new opportunities that arise.

Because they are embedded in a complex matrix of practices and systems, capabilities are harder to develop, duplicate, and copy than are most competencies. Most people who visit 3M to study how it maintains such an outstanding record of innovation have the same reaction: what 3M does cannot be duplicated in most other companies. They correctly recognize that 3M’s organizational capability to innovate does not rest in a single set of skills or a limited set of practices that other organizations can easily copy.

Similarly, a Six Sigma quality capability is not easily developed because it involves a number of organization design features, including the employee selection process, training programs, corporate vision statement, and senior management’s behavior. It is not based on any one system or practice; rather it permeates the organization. A capability is more difficult and costly to imitate when it is based on multiple systems and practices that mutually reinforce one another.

Once Motorola recognized the value of its Six Sigma capability, the company began selling it. It offered training programs through Motorola University and sold written materials. It found a number of buyers, including General Electric (GE), which ended up developing a successful Six Sigma capability of its own. Not surprisingly, a number of the buyers were unable to develop a quality capability that led to a competitive advantage.

One of the important points to remember about organizational capabilities is that they do not exist in only one group or function, in the heads of a few technology gurus, or in a small set of functions or patents. In reality, they reside in the many systems and relationships that exist in an organization. They lie in a synergistic combination of individuals and systems that forms the organization’s way of operating.

Competencies are different; as characteristics of the organization’s technical core they can reside in particular functions, groups, or even individuals. For example, in the late 1980s, the military avionics division of Honeywell received almost 100 percent of the contracts related to human-technical interfaces in helicopters because of the skills and knowledge of one engineer who was the acknowledged leader in the field.

How long an organization can derive a competitive advantage from its core competencies depends on where these competencies are and how easy they are to copy. In general, competencies are easier and less costly to imitate than capabilities. For example, many organizations can duplicate core competencies that are contained in the minds and skills of a small number of employees. These core competencies walk out the door every night, and when they are not treated right, they might not come back.

One of the most dramatic examples of how competencies can spread is Fairchild Electronics, which in the 1970s pioneered the development and production of semiconductors. Fairchild had a high level of technological competency, but a well-deserved bad reputation when it came to the way it managed and treated employees. This made it difficult for Fairchild to maintain its technological advantage. Rather quickly, the pioneering development work it did on semiconductors was lost. When they left, employees simply took with them the knowledge that was part of Fairchild’s core competency in semiconductors and used it to start competing businesses that were better managed. The new companies—Intel, AMD, and others—are now among the most successful semiconductor firms in the world today. Fairchild is out of business.

Finally, to result in a competitive advantage and make a durable contribution to performance, competencies and capabilities must be leveraged by the organization. Amazon’s “single store” strategy transformed the organization from an Internet retailer to a platform for commerce. Its long-term agreement with Toys “R” Us, for example, allows Amazon to leverage its competencies and capabilities in customer experience, customer filtering, order fulfillment, transaction processing, and customer assistance.

In sum, competencies and capabilities have several similarities but also some important differences. Both competencies and capabilities are dynamic and can change, sometimes rapidly. They both add value, can be sources of competitive advantage, and can be very complex routines of behavior, skill, and knowledge. At the same time, they are different: competencies are more like assets in that they can reside in people and can be acquired quickly if they are not legally protected, whereas capabilities are truly an organizational characteristic. Competencies are based in science, technology, and engineering, whereas capabilities are based in processes, routines, behavior, and systems. Finally, competencies are related to the technical core of an organization, whereas capabilities can be related to any part of the organization’s operations.

Designing Integrates the Organization

The third process in the Built-to-Change Model involves designing the structures and processes that enable an organization to perform effectively. It and creating value are the two processes that contribute to effectiveness by determining how and how well a strategy is implemented. To deliver on the promise of its identity and intent and create the right competencies and capabilities, an organization must be designed correctly. It must design and implement supporting structures, attract and retain key human capital, develop and deploy appropriate information systems, develop effective leaders, and craft motivating reward systems. Designing is a dynamic process of modifying and constantly adjusting an organization’s structure, systems, people, and rewards so that they provide the called-for performance.

Dynamic alignment exists when all of the pieces in the designing and creating value process are evolving in the same direction and in support of the strategic intent. Dynamic alignment is created when the strategic intent drives the nature and quality of an organization’s competencies, capabilities, and design.

Both Dell and Gateway have the same strategic intent: to be affordable PC manufacturers. In both cases there is good alignment with their respective environments and identities. In other words, they both have done a good job of identifying who they are and the requirements of success. However, Dell has done a better job of designing itself, and as a result it has consistently performed better than Gateway.

Designing is the nitty-gritty work of creating a b2change organization, and we look at it in detail in Chapters Four through Ten. There we focus on how to structure organizations, develop measurement systems, manage talent, develop leadership, and build reward systems.

Configuration and Alignment Drive Performance

Earlier, we suggested that effective organizational performance over time involves two primary and time-based relationships: the one among the environment, a company’s identity, and its intent, which we called the critical configuration, and the one among identity, intent, capabilities, competencies, and design, which we called dynamic alignment.

Virtuous Performance Spirals

There are times in an organization’s life, decades long in the most extreme cases, when what the organization does and how it does it remain in close proximity with environmental demands. This is the Holy Grail of organization performance—when both critical configuration and dynamic alignment exist for long periods of time. It results in what is called a virtuous spiral, because “everything comes together.”4

Structure and capabilities that support a good strategic intent generate revenue that boosts the rewards for employees, and increases their motivation and commitment. The more challenging and rewarding work environment that results creates innovative ideas and further reinforces the organization’s ability to attract, retain, and develop effective employees, who further positively affect performance. Thus a virtuous spiral forms and expands, matching the expanding environmental potential, and carrying the organization and its members to greater levels of performance. Virtuous spirals thus represent a potentially powerful competitive advantage that is valuable, rare, and hard-to-duplicate.

Nike represents a good example of critical configuration and dynamic alignment that has created a virtuous spiral. Phil Knight’s idea to source the manufacturing of athletic wear from low-cost Asian manufacturing sites was a brilliant idea at a time when fitness and health were increasingly important parts of the social environment. This manufacturing strategy allowed the organization to develop a set of competencies and capabilities that created value for its manufacturers, sales and distribution channels, employees, and customers. The company fostered a “just do it” identity that was reflected in its structure, the people it hired, the lack of formal systems, and the way it rewarded people for contributing to the organization. It became one of the most successful organizations of the 1980s and 1990s.

Microsoft’s virtuous spiral began with a strong critical configuration. Bill Gates’s licensing of MS-DOS to IBM and the subsequent growth of the PC industry created an enormous economic opportunity. But that critical configuration alone is not enough to explain Microsoft’s continued success. The company has also enjoyed a virtuous spiral relationship with its people for decades. Since the early 1980s, Microsoft has had an internal environment in which its employees have done well and the company has done well. The employees have had challenging work and, of course, one of the most highly rewarding stock plans around. Microsoft is routinely ranked as one of the best places to work, especially for high performers, and has thereby attracted some of the country’s top software engineers and marketing geniuses.

Because of its relationship with its human capital, Microsoft has been able to generate a powerful dynamic alignment in which success begets success, which in turn begets more success. The company’s seemingly unstoppable growth began to slow down only in the late 1990s, when it faced a rapidly changing competitive environment along with government challenges to its growing power. But even in the market downturn of the early years of the new century, Microsoft largely continued on a virtuous spiral of increasing growth and success.

Procter & Gamble (P&G) is a great example of an organization that has a strong dynamic alignment. Though the company is over one hundred years old, the past forty years of its existence have been marked by many forward-thinking efforts to establish a virtuous spiral relationship with its employees based on employee involvement and the development of leaders throughout the company. P&G was an early adopter of employee involvement practices in its manufacturing plants. It also has a stock ownership plan that has placed over 30 percent of its stock in the hands of its employees.

Another organization that has clearly enjoyed a virtuous spiral of success for decades is GE. Even before Jack Welch became CEO in the early 1980s, GE established an environment where highly talented individuals wanted to work because of the opportunities the company offered for career development and financial rewards. Able to attract and retain highly talented individuals, GE has enjoyed decades of enviable growth in profits and as a result has attracted highly talented individuals. GE is a clear example of successful performance leading to successful recruitment and motivation of individuals, which in turn produces even more successful performance.

Environmental Change Shatters Configurations and Alignments

Environmental change is the single biggest threat to virtuous spirals and sustained effectiveness. Because it is largely out of the control of most organizations, environmental change often threatens what once was an excellent response to the demands of the environment. It can render obsolete the competencies and capabilities that created value, and can disrupt dynamic alignment by altering what people need to do and how they should work together. It is precisely because change is such a threat that virtuous spiral organizations need to be sure they can change when they need to.

IBM is illustrative of an organization that has been able to respond to environmental change. It started as a timecard company, but environmental changes (technology) ruined that business. It was able to transform itself into a computer manufacturing company. As a computer company, IBM developed a long-term virtuous spiral relationship with its employees, but its business model began to fail in the 1980s when major environmental changes again occurred. IBM reacted to the decreased profitability of its computer hardware products by breaking the loyalty-based employment relationship it had established over many decades. The company ordered extensive layoffs and broke commitments to employees in the areas of retirement and careers. In some important respects, it changed parts of its identity but still maintained others.

Only in the late 1990s, when IBM established a credible new strategic intent that emphasized services and consulting, was it able to improve its performance and reestablish a virtuous spiral. For the past few years it has done an impressive job of creating a virtuous spiral that relies on an employment relationship based more on skills and performance than on loyalty, a relationship that fits its strategic intent.

There is no hard-and-fast rule concerning how often companies need to make major changes in their strategy. It depends on the type and pace of change in the environment. Some virtuous spiral companies have never needed to alter their strategy. Southwest Airlines has essentially executed the same strategy for over thirty years. That strategy has continued to be a successful one and enabled Southwest to sustain a virtuous spiral relationship with its employees without making major changes in its organization design. Can Southwest continue forever without changing? Probably not! Eventually it will have to change its strategy because of the appearance of new competitors, regulatory changes, or some other environmental change.

Other virtuous spiral organizations have successfully made strategy changes by reinventing themselves in ways that improved their competencies and added new capabilities. A great example is Dayton Hudson Corporation. It recognized that traditional department stores were not necessarily the best place to be in the retail market. They followed up on this conclusion by creating Target, which today is among the most successful retail businesses in the world. Indeed, Target may end up as the only major competitor for Wal-Mart. It has been so successful that Dayton Hudson has adopted Target as its corporate name.

Changing its strategy in the retail business required Dayton Hudson to become more focused on costs and the way it managed its inventory and purchasing. However, the company stayed true to an important aspect of its identity: its approach to corporate governance and human capital management. It had and still has a very strong emphasis on building a virtuous spiral relationship with its employees. As a result, the organization has been honored both for its excellence in corporate governance and for its human capital management practices.

Intel is another virtuous spiral company that was forced by environmental change to make a major strategic shift. Once very successful in the DRAM chip business, Intel realized in 1985 that it needed to exit that business because it could not win against its Asian competitors on the basis of cost. It switched to microprocessors, and the rest is history. As we all know from its memorable marketing campaigns, Intel has now become the major supplier of microprocessors to PC manufacturers. It is one of the few Silicon Valley start-ups from the 1960s and 1970s that is still thriving.

Unfortunately, most organizations are unable to make one, much less two, major transformations in their business models. They typically enter a fast or slow death spiral and eventually go out of business. Major change is extremely difficult because it often requires the development of new core competencies and organizational capabilities, and changes in structures and systems that were built for stability. Indeed, economists have come to refer to corporate failures caused by dramatic changes in the political, economic, or technological environment as creative destruction. The term was first coined by the late economist Joseph Schumpter and has since been widely adopted.

Death spirals can be avoided and reversed. Creative destruction is not inevitable. Organizations can be successfully changed. It is not easy, but it can be done if the design of the organization is one that facilitates change.

Dynamic Model

The b2change approach reflects a philosophy of building an organization that is able to maintain critical configuration and dynamic alignment even in the midst of environmental change. Figure 2.2 presents a dynamic virtuous spiral model of what needs to happen for an organization to maintain configuration and alignment. It shows that maintaining an upward spiral of higher and higher performance requires cycles of strategizing, creating value, and designing. To maintain configurations over time, organizations need to be created “change ready.” They need to be able to change elements of their strategy, competencies, capabilities, and design whenever the environment calls for it.

The IBM and Microsoft examples are important because they clearly show that environmental change is the single biggest threat to virtuous spirals. It can disrupt any configuration or alignment of identity, intent, capability, and design in very short order. Organizations that rigidly stick to a strategy, capability, or design are bound to fail; it is only a matter of time.

FIGURE 2.2. Dynamic Virtuous Spiral

Conclusion

Most traditional bureaucratic organizations are unable to reinvent themselves in timely ways when faced with major technological, political, or economic change. They are built on the logic that stability is more profitable than change. The b2change approach reflects a different philosophy. It suggests that an organization can be built to dynamically match its strategizing, creating value, and designing processes to the rhythm and substance of environmental change.

To change rapidly and maintain critical configuration and dynamic alignment, organizations need to be designed to change and be capable of high-velocity change. They need to be able to change elements of their strategy, competencies and capabilities, and organization design when the environment calls for it.

In the chapters that follow, we will describe the building blocks of virtuous spirals—the key features and principles of strategizing, creating value, and designing. We describe how each process can be built to change and can be configured and aligned with the others over time. We will show how, by using the right processes and designs, it is possible to build an organization that both performs effectively and changes when needed. We begin with the process used to create and change an organization’s strategic intent.