10

Dialogue for Alignment

The way of paradoxes is the way of truth. To test reality we must see it on the tight rope. When the verities become acrobats, we can judge them.

—Oscar Wilde1

How do you get a team of top leaders to fully understand each other's point of view? And to aim for the same targets and outcomes? You often can't, at least not easily, especially if you're talking about a big company. Even the best executives can't fully detach themselves from their biases and personal motivations. The truth is, you can bring a group of leaders to the trough of engagement with each other, but you can't be sure they will drink.

That was the problem faced by Cameron Clyne, CEO of National Australia Bank (NAB), a company we mentioned in Chapter Two. Clyne sought to have his top leaders gain an enterprise-wide perspective, a viewpoint that would help them improve their management of the company as a whole, as opposed to just championing its parts. He had already tried changing everyone's goals and rewards to motivate them to align around a holistic view, but he was dissatisfied. Now he was trying another tactic instead: dialogue.

By dialogue we don't mean crowded conference calls and e-mail correspondence copying thirty people. We don't mean one-way communication of vision and goals from the boss to the troops. And we don't mean horse-trading intelligence over the Internet. We mean face-to-face, give-and-take conversation in which people have the time to appreciate how the other participants think and feel.

Clyne was particularly interested in having his top executives align their views on resolving the tension between longstanding contradictory goals: investing to grow market share and saving to bolster the bank's balance sheet (capital ratio, funding ratio, loan-loss provision, and so on). When Clyne tried to gain agreement, his executives debated the issue, some arguing for cutting costs while others for investing in new products or capabilities. But they couldn't gain consensus, and Clyne had to make the decision himself.

The executives were trapped by their own perspectives, so Clyne took a chance. He paired executives who disagreed with each other. He asked them to retreat to a place away from the company office and develop a point of view that represented a third colleague's perspective—whether the colleague led personal banking, business banking, wholesale banking, wealth management, risk, finance, human relations, technology, or whatever. These were people who knew each other mostly from meetings. They didn't regularly walk into each other's offices or go to each other's staff meetings.

Not surprisingly, the paired executives returned with brand-new proposals—fresh, spontaneous ideas for tapping new market opportunities, new efficiencies in technology use, and new savings from sharing resources. Clyne had never heard these ideas before. Instead of the executives pressing him to make either/or decisions, they were proposing both/and ideas, in particular a more integrated banking operation. That's just what Clyne was looking for. And today, the bank's strategy prescribes a transformation from five operating units to a single integrated architecture with common services, common product platforms, single customer files, and a single back-end across the enterprise.

This came from executives' abandoning the habit of passionately advocating only their point of view—a first for the group. It also came from understanding underlying motivations—for example, that however much executives wanted the bank to succeed, they unconsciously had sought first to expand their own unit's control. And with better understanding of themselves and others, they could work together to come up with options they'd never considered before.

The first option is to teach others. This may begin with simply helping others see they are dealing with a paradox, and they can go beyond the either/or thinking that has driven their dead-end conversations. An executive at a leading technology company says, “What makes up a culture in technology are technologists. And they are binary thinkers. We have five thousand binary thinkers in situations that aren't binary. It's a challenge for me. How do you get them to think about the ‘and’?” Awareness through dialogue that you're not dealing with just a puzzle is the first step.

A second objective is to solicit opinions and ideas. Many people today persist in thinking dialogue is a way to convey their message. But dialogue is a way to understand others' interests—and the reasons why they act as they do. We all have limited perspectives, and our ability to learn from others determines our ability to handle paradox successfully. Dialogue helps you elicit views in ways that make others feel safe, valued, and heard. One executive we know put together a cross-functional team to have a heart-to-heart discussion about the company's portfolio strategy. Although the executive didn't normally convene a team for this purpose, he decided to solicit views on synergies, pitfalls, paradoxes, and history. The dialogue allowed him to work out disagreements and create alignment. That in turn ended the problematical pattern of flip-flopping every month, which had been a reflection of lack of strategy.

A third objective is to challenge assumptions. Susan Scott, author of Fierce Leadership, writes, “The truth will set you free—but first it may thoroughly irritate you.” You must be willing to examine your own assumptions, which may happen through challenges from others. You may find it hard to recognize the beliefs you're clinging to—“bigger is better,” “inspect what you expect,” “the boss decides,” “take care of number one first,” “facts trump feelings.” Such unconscious assumptions often lead us to ignore a paradox or defend one resolution of the paradox and discount another. Jaap Jonkman, formerly vice president of talent at NAB, notes, “Under every argument there is an underlying assumption. [We need to] look at the subtext that [makes us think] we should be doing something one way or the other.”

A fourth objective is cultivating and demonstrating empathy for others. We work with one global company in which the finance staff views the business unit leaders as spendthrifts who can't be trusted. The business unit leaders naturally see finance people as micromanaging control freaks. The CEO sees himself as the arbiter of constant conflict. We encouraged uncensored and open-ended conversation to help people grasp why other individuals defend their positions so passionately. Even if people don't agree, they can gain more tolerance and appreciation for alternative positions—and in turn integrate elements of them into their thinking. In many jobs, people limit conversations to their inner circle, which only entrenches a single viewpoint.

The final and overriding objective is to align interests based on a higher mission. You want this alignment whether you take a purpose, reconciliation, or innovation mindset. Bringing the conversation around to a larger aspiration can mitigate conflicts and break deadlocks. That's what helped Cameron Clyne jar his top leaders into recognizing that they had been too narrowly focused on partisan views. They could instead co-create something better.

Dialogue today has become a skill in decline. A number of factors seem to come into play. First among them is the speed of business and the distances that separate colleagues. Many people schedule their workday in fifteen-minute segments and interact with virtual team members around the world. They don't give priority to dialogue that helps the whole company. We worked with one bank executive who, in meetings of the top team, viewed his role as representing and defending his function, always subtly looking for an advantage. He described his role as similar to being a member of the U.S. Congress, defending states' rights against the encroachment of the federal government. He was thus unable to engage in conversation that didn't end up in debate, conflict, or superficial agreement to be undone by later actions.

Other factors that make dialogue hard relate to your skill. Some people don't or can't deal with the ambiguity and confusion a paradoxical problem poses. They fail entirely in jumping over the line when the conversation heads into gray areas. One executive says, “Some people are more intuitive and can act [on paradox] with incomplete information, but we aren't wired the same.” Others remain so relentlessly logical and rational that they cannot get their minds around the notion of paradox. Still others simply tense up, and the tension triggers the derailing behaviors covered in Chapter Three—such as becoming distrustful or arrogant or volatile.

The Practices of Dialogue

Many books have been written on dialogue and conversations, but we highlight five techniques we use regularly to help clients resolve paradoxical problems through meaningful dialogue:

- Pose transcendent questions

- Facilitate role-playing

- Structure and monitor the conversation

- Provide 360-degree feedback

- Follow a framework

These practices are much more useful than unmanaged, free-wheeling discussions or brainstorming. We discourage those activities, as they often lead to recurrent debates with each side digging deeper into the ruts of bias.

Practice 1: Pose Transcendent Questions

You've probably heard the old joke: “What did the monk say to the hot-dog vendor? ‘Make me one with everything!’” Keep that in mind when conducting dialogue. The vendor may be focused on the elements of dressing the dog. The monk (or leader) needs to stay focused on a more transcendent end point. Here are a few questions to that end:

What will our industry look like in five years, or twenty years; how must our organization change given the future state; what is our long-term strategy?

What is the bigger issue than the paradox we're experiencing? What's important to our customer (patient, consumer, user), and what's crucial for other stakeholders?

What are competitors doing that we can learn from?

How would we like things to look in the short term, say, three years; what do we need to do to achieve that three-year picture?

Practice 2: Facilitate Role-Playing

As in the case of Cameron Clyne, a common way to deepen dialogue is to have people play different functional roles—finance chief plays marketing boss, say. Another form of role-play is illustrated by an exercise in a recent executive program we ran at one of the world's largest banks. The CEO asked us to write a case depicting a recent acquisition, a transaction that triggered a clash of opinions over the risk versus return of the joined banks. In discussing the case, the executives each took on the role of a different colleague.

The resulting role-play was illuminating. The same debate from a couple of years earlier replayed itself, when the CEO had to simply overrule people with strong opposing views. This time, however, people couldn't summon the same certainty of argument or passion of conviction, because they could see more sides of the debate. The CEO concluded the exercise by saying, “Why can't we do this in our regular executive meetings?”

Practice 3: Structure and Monitor the Conversation

In free-form dialogues, people's emotions get in the way of thinking in purpose-driven, balanced, or innovative ways. If you're the leader, you need to separate emotions from issues by structuring conversations: Acknowledge up front that everyone has a different personal purpose and values. Make sure the participants all have a chance to talk about their own hot-button issues. Allow people to express their self-interest, reasoning, and motivations. Clarify how different people are fierce proponents of clashing views. Recognize your own emotional attachment to a position. Then seek alignment.

Note that alignment does not mean unanimity. People will disagree to the end on some issues. But you can bring about consensus in spite of disagreement. You need to show you want to hear people's views and demonstrate that you are willing to vet the views and put them in context of a purpose, reconciliation, or innovation mindset. With alignment in hand, even people who agree to disagree can then look for actions that strike everyone as acceptable.

Think of monitoring as a separate task in a structured dialogue. Keep track of the emotions attached to arguments. Breakthroughs tend to come on the wings of rising emotions. We have found that the first sign of conversational progress may be an expression of gratitude, shared laughter, or empathy. One executive we interviewed noted that when her team began to make progress, people would distance themselves from the talking points they carried to the meeting. “It's as if they lean back from the table or push their notes away, and then I know they're moving to a higher level of discussion.” Whatever outward gesture you observe, seize the moment and seek alignment.

Practice 4: Provide 360-Degree Feedback

Many times people honestly don't know what roadblocks they have thrown in the way of the dialogue. We worked with one investment banker who regularly assembled first-rate, multimillion-dollar private-equity deals. We first performed a 360-degree feedback exercise for him, polling colleagues, reports, and clients to understand his work habits and behaviors. We found he considered his most productive time as that spent building ties with CEOs, studying financial statements, and nurturing outside relationships. He didn't spend much time with staff, gaining alignment in conversation. As a result, his staff ran in different directions, developed conflicting views, and spent time on the wrong things. The simple unveiling of this managerial blind spot allowed him to discover what should be his most productive time: dialogue with staff, deepening understanding and aligning their efforts.

Practice 5: Follow a Framework

Conversations to manage paradox can be tricky to orchestrate. People get embroiled in heated, circular debates, and they end up talking about a wicked paradox as if it were a tame problem they could solve like a math equation. To improve the dialogue in the face of paradoxical problems, we find it helpful to work with frameworks to clarify concepts and get everyone to understand the dynamics at play.

We often team up with colleagues Mickey Connolly and Richard Rianoshek, coauthors of The Communication Catalyst.2 Connolly and Rianoshek cite three axioms of human communication:

- All humans have purposes (things they're for), concerns (things they're against), and circumstances (constraints within which they have to work).

- When people perceive you are unaware of or opposed to their purposes, concerns, and circumstances, they will resist, producing waste.

- When people perceive you are aware of and sensitive to their purposes, concerns, and circumstances, they will communicate and collaborate, producing value.

Connolly and Rianoshek advise leaders to “look for the intersections” (Figure 10.1). Alignment comes from the intersection of your view, composed of your purposes, concerns, and circumstances; my view, composed of the same for me; and the facts or circumstances that will guide our actions. As the leader, shape the conversation so that people all express their own views and identify common ground. With a shared view of interconnections, you can then turn to ideas for managing the paradoxical problem at hand.

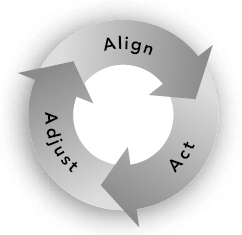

Another framework we like to use addresses the fact that no action to resolve paradox lasts for long, so as circumstances change, and as you learn from experience, you have to adjust. That brings into play what Connolly and Rianoshek refer to as the Cycle of Value (Figure 10.1). The Cycle of Value shows how learning occurs, and it is readily applicable to the cyclical nature of managing paradox in an ongoing, iterative way. Creating cycles of value is the goal of any leader using conversation to address paradox. Ideally, the rate of learning is equal to or greater than the rate of change, which today means revisiting paradoxes and revising action multiple times a year.

Figure 10.1. MSFind Intersections for Alignment

Source: Mickey Connolly and Richard Rianoshek, The Communication Catalyst (Chicago: Dearborn Trade, 2002), 56.

Figure 10.2. MSThe Cycle of Value

Source: Mickey Connolly and Richard Rianoshek, The Communication Catalyst (Chicago: Dearborn Trade, 2002), 73.

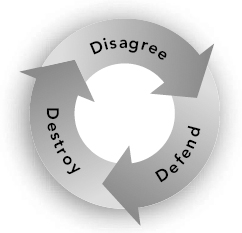

Figure 10.3. MSThe Cycle of Waste

Source: Mickey Connolly and Richard Rianoshek, The Communication Catalyst (Chicago: Dearborn Trade, 1001), 13.

Connolly and Rianoshek note that leaders require vigilance in detecting signs of the Cycle of Value's evil twin, the Cycle of Waste (Figure 10.3). Whereas the Cycle of Value has at its core alignment of purposes, concerns, and circumstances, the Cycle of Waste begins with disagreement. This disagreement stems from the either/or position—an entrenchment inside of my view and the unwillingness to explore yours. Disagreement yields defensiveness, and the accompanying emotions spur participants to destroy the validity of the opposing point of view. This happens all the time in companies that face paradoxical problems but cannot acknowledge them. It is especially common in matrix organizations, where the opposing forces of paradoxes enter almost every key decision, and leaders have to work hard to keep the Cycle of Value turning, one round of alignment after another.

We recently worked with one client that was attempting to install a major human resources system throughout the world. Up until the launch of the system, the finance and human resources directors did not agree on who should have responsibility for payroll and did not fully trust each other. Much of the planning for the “go live” day was accompanied by either/or disagreement. Predictably, the system launch did not go well. Many employees did not receive their paychecks, the database was not sufficient to make accurate decisions, and multiple system glitches compounded the problems. People started pointing fingers at each other, and the company spiraled into the Cycle of Waste. A fact-finding study was launched, key people lost their jobs, and the lessons of the cycle of waste were costly for everyone.

Patience, the Virtue in Dialogue

One of the biggest challenges for leaders conducting dialogue is that it requires patience, which takes time, and in the interim you risk having people accuse you of indecisiveness. This is a hazard you should brace yourself for. Rest assured, though, that most such criticism is premature. Time after time, we have orchestrated conversations that evolve to entirely new places after six or nine months. That comes from multiple conversations, feedback, reflection, and growing engagement in managing paradoxes the right way.

We worked with leaders of a large pharmaceutical company who faced the need to cut costs by $4 billion while boosting revenue 10 percent. Predictably, finance people talked only about cost cutting, commercial leaders about hiring more sales reps, and R&D leaders about investing more in research and development. The leadership team deadlocked on an overall plan early on, but six months later, after much rumination about possible options, they agreed on a balanced approach—combining multiple sales channels, eliminating select sales reps, using social media to connect with doctors and patients, and eliminating some work tasks while redesigning others.

What often takes time is overcoming the natural human belief that other people know most of the things we do. All of us accumulate knowledge or experience that causes us to assume others have accumulated the same. It's a human weakness. In what has become known as the “tapping experiment,” conducted at Stanford University by Elizabeth Newton, subjects were designated as either “tappers” or “listeners.” The tappers were asked to list twenty-five songs they believed the listener would likely know. They were then told to tap out the rhythm of the songs so the listeners could identify them. Before starting, the tappers predicted what percentage of songs the listeners would get correct. As it turned out, the tappers wildly over-estimated at 50 percent. Listeners could identify only 2.5 percent of the songs.3 The lesson: When you know something, it's hard to believe other people you work with don't know it as well.

Put another way: When the music is so loud in your own head, it's hard to imagine that others can't hear the same tune. That's why patience matters. Dialogue over time helps people hear each other's music.

One final tip for helping this process along. It comes from John Gottman, a marriage counselor who wrote The Seven Principles of Making Marriage Work. Gottman coined the “the 5 to 1 ratio,” arguing that in successful relationships, people have five times as many positive interactions as negative ones. Moments of agreement, expressions of gratitude, asking questions, being nice, showing empathy and kindness—these all occur five times as often as the moments of criticism, anger, and hurt feelings.

Gottman's findings can be extrapolated to the workplace. Interviewed by Harvard Business Review, Gottman noted: “You could capture all of my research findings with the metaphor of a saltshaker. Instead of filling it with salt, fill it with all the ways you can say yes . . . ‘Yes,’ you say, ‘that is a good idea.’ ‘Yes, that's a great point, I never thought of that.’ ‘Yes, let's do that if you think it's important.’ You sprinkle yeses throughout your interactions—that's what a good relationship is.” What Gottman is describing is the importance of affirmation—an essential tool in finding the intersection between people's values, concerns, and points of view.

And this furthers alignment more than many other techniques, bringing people to the point of understanding what they're all for. But this won't happen unless you, as a leader, set the emotional tone for it, allowing people to air what they're against but seeking alignment for larger, shared objectives and actions. Sometimes this is the reason people believe dialogue is only a soft, feel-good, time-eating procedure to buy peace among adversaries. But affirmation helps surface the best options and leads to better decisions, execution, and results even in pressure-cooker situations.

We wish the world at large would value dialogue more, and not downplay the value of person-to-person conversation in resolving contradiction. Too many of us retreat into social cocoons with people of similar minds and passions. We fail to look out the window to take in diverse or adversarial opinions and instead keep our gaze facing into a mirror reflecting only people like us. In work, in politics, in international relations, this only adds to partisanship. Consider the deadlock in your workplace, in your community, among your elected officials. Dialogue in search of alignment could unlock the solutions needed to solve the paradoxical problems of our time.

You have to wonder: What if everyone jumped over the line together? But of course that doesn't often happen. People don't have the training, or the inclination. People may start with “yes, that's a good idea,” but they soon sense a battle and say, “no, that's a non-starter.” Peace turns to poison. And that brings us to the next and last of our tools for managing paradoxes: dealing with conflict.