12

Developing Yourself

The curious paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, then I can change.

—Carl R. Rogers1

Chapter One started with the story of Ron, the COO of one of the world's best-known brand-name companies. He mistook paradoxical problems for puzzle-like ones, attempting to exercise complete control to the exclusion of regional managers. In the process, he missed the value of using collaborative tools, in particular stakeholder mapping. In this chapter, we highlight another lesson: To manage paradox in collaboration with others, you have to be able to manage yourself.

It's worth taking another look at Ron's story, emphasizing this personal-management angle. Ron was acerbic, highly intelligent, quick, and had a great track record. He routinely came up with a string of knockout marketing ideas. What he wasn't so good at was getting others to align with his ideas and buy in to them. People were intimidated by his genius and unable or unwilling to rally behind his initiatives. In fact, they called him the “brilliant asshole.”

He was not aware of how others saw him. He believed that, while his style was sometimes abrupt, others could see that the ends he accomplished more than justified his aggressive means. A 360-degree feedback exercise, however, revealed that people were so intimidated they refused to challenge him or offer ideas that they believed would be shot down. They believed he wouldn't listen to other points of view and was operating on false assumptions, riding roughshod over their positions. People said they'd like to tell Ron: “You're not as good as you think you are, and no one is signing up for what you want them to do.”

Ron's failure to manage himself is all too common among senior leaders. Too often, people do not adequately develop the interpersonal skills for collaboration, do not get beyond the thirst for control, consistency, and closure, do not work to mitigate their personal derailers, and do not overcome the human reluctance to act in the face of ambiguous, paradoxical problems. If you're a leader, you may be outstanding at accomplishing tasks, but you may have neglected your ongoing development as a paradox manager.

Upon getting feedback, Ron realized that it didn't matter if his ideas were great if nobody wanted to pitch in to make them succeed. He resolved to change. In the weeks following, he made a conscious effort to ask people for their opinions; to listen seriously and respond to what they had to say; to back away from his impulse to believe he was right when he doubted others; and to change his mind in front of other people. His colleagues began to respond to him in a new way. Many people were surprised that beneath that haughty exterior beat the heart of a genuinely nice guy.

Getting Fit as a Paradox Leader

Despite being elevated to jobs where problems are full of contradictions, many leaders initially lack the mental and social muscle to function as paradox leaders. When they worked their way up through lower levels in their organizations, they did not deal with the daunting challenge of complex paradoxes. How about you? Are you fit to work with a team collaboratively to solve paradoxical problems? Have you personally developed yourself to manage in a world where paradoxes make up most of your difficult decisions? And if not, what do you need to do to become fit?

A picture of what's required emerges from a study of twelve top management teams across nine diverse business sectors. Researchers Wendy Smith, Andy Binns, and Michael Tushman sought to identify the behaviors of teams that managed paradoxes successfully. They found four characteristics that led to success: First, the teams experimented with new behavior they believed would be needed to lead and manage their organization in the future, and not just today. Second, they built an overarching vision that encompassed both traditional and new ways of operating. Third, they learned and debated how to operate in a more complex environment—they held seminars with outside experts, scanned the environment for signs of changes that would affect their businesses, debated the relevance of new ideas, and stretched themselves to think paradoxically. Fourth, they deliberately sought conflicting perspectives and engaged in conflicting dialogue.

These findings corroborate our experience, and we believe the four characteristics stem first from the ability of individual leaders on the team to release their firm grip on control, consistency, and closure. Team members cannot fruitfully collaborate if someone always insists on controlling the outcome while excluding others. Nor can they do so if someone insists on acting consistently with old mental models even as times change. Nor can they act effectively if everyone demands closure on problems that need frequent revisiting. They can succeed only when they work among others who know that control, consistency, and closure work well for straightforward, puzzle-like problems, but are wholly inappropriate for the paradoxes of work and life.

Another essential factor in managing paradoxes is trust. John Veihmeyer, CEO of KPMG, notes, “It is not always the speed and ability to make a decision [that matters], but how much . . . the people you need to be involved in the decision trust and respect each other.” You can think of trust as the glue that holds people together. Its absence makes it virtually impossible to explore unknown or untested ideas, or to collaborate when tension ramps up in dealing with complex challenges.

In practice, we believe the most visible factor that sets apart developing from developed paradox leaders is the learning that comes with dialogue, debate, and experimenting, as the Smith, Bins, and Tushman research suggests. John F. Kennedy said it best: “Leadership and learning are indispensable to each other.” Developed leaders are eager to acquire knowledge, even if it contradicts their beliefs. They don't retain control of the conversation; they extend control to others. They try to stretch themselves in new ways. We suggest asking yourself the following questions to get better at dealing with paradoxical problems:

- How comfortable are you with uncertainty? Do you rush too quickly to find a solution to complex problems? Do you exhibit the patience required to find the right approach?

- Can you take action in the face of ambiguity and avoid paralysis when the solutions to your problems are not obvious?

- Do you frequently solicit ideas and opinions from individuals outside your function? Your organizational level? Your organization? Your industry?

- When heated arguments take place on your team, do you take a step back to help people find areas of alignment? Or do you wind up taking sides and trying to win the argument?

- When was the last time you changed your mind after hearing someone voicing a position that you hadn't considered before?

- How fast do you form opinions and make decisions? Do you jump to conclusions early or after a period of discussion, thought, and questioning?

- Do you spend enough time requesting feedback and reflecting on what you hear?

- Do you try to cut through the clutter of complexity and ambiguity by finding the simple, straightforward course of action?

- Are you aware of your weaknesses and how they they're related to your strengths?

- When you take a position on an issue, do you consider the downside of the position and the upside of the opposing points of view?

- Do you ever admit you're wrong? Are you able to veer from a stance you've taken for months or even years when you see a better option?

- How often do you encourage people to come up with fresh alternatives to the conventional wisdom or the standard answers? Do you have tolerance for taking the less-traveled path?

- How often do you use contrarian thinking? Do you ever consider doing the opposite of what's expected? How many times have you actually done the opposite?

These questions help you assess your vulnerability, openness, consciousness, and willingness to move outside your comfort zone for fresh thinking and approaches. It's easy to fool yourself into believing you're a learner. Most people would never acknowledge that they don't learn from their experiences. In most companies, few people see themselves as rigid, closed off to fresh thinking, or unable to take risks and embrace the unknown.

We once worked with a company where the biggest problem was often people's need to be right. After going through the strategic planning process, leaders ignored challenges, refused to look at new data, and were unwilling to say they might have made some mistakes. They became stuck on the puzzle side of the line, shoes glued to the pavement.

People can unwittingly close themselves off to new ideas, the opinions of others, and feedback that doesn't conform to their own views. This stems from their listening only to their own inner circle. Or it results from failing to cultivate a network of people who can provide the insights and perspectives necessary to understand how paradoxes can be managed. All of us operate out of at least some allegiance to our existing positions. Many of us aren't even aware how we reflexively shut down people who beg to differ.

Becoming a complete leader who is skilled at managing paradox takes time. The following points summarize what we've suggested so far—behaviors to practice over an extended period. These will expand your capacity for leading groups in managing paradox. Note how straightforward they are—and yet endlessly difficult to execute:

- Practice control selectively: When you take control, ask yourself: Would I get better results by giving it away?

- Recognize foolish consistency: Be consistent in your words and actions, but understand when it's time to change your mind based on new information or changed circumstances.

- Tolerate a lack of closure: When you encounter a paradox, tell people at the start that closure is not the goal. Instead, the goal is to understand what action to take now, while expecting to revisit the challenge over time.

- Invite honest feedback: Becoming aware of how your approach to paradoxes is seen by others can give you insight on how to manage them more effectively.

- Solicit the greatest diversity of input possible: Too many leaders rely on a tight-knit coterie of trusted voices. As David Jensen, a research and educator on leadership, says, “A closed mind is a wonderful thing to lose.”

- Reflect on what you hear: Give yourself time and space to absorb what you learn. Ask yourself: “What if the people I disagree with were right? How would things play out? What do they know that I don't?”

- Change small behaviors: Start small and build up to a more developed leader one habit at a time. Use a “test and learn” process.

- Focus on building and maintaining trust: Hugh McColl, the former CEO of Bank of America, often pointed to the “paradox of trust” for senior leaders: “When you are the top, you must earn the trust of people while you, on the other hand, must extend trust to others.”2

- Become comfortable with impossible organizational goals: The appearance of unachievability often stems from paradox. For instance: Reduce expenses by 25 percent and grow revenue by 25 percent. To prepare for this, move to a continuous reinvention mentality.

- Reconcile fact-based and intuitive judgment: With today's time pressures, leaders must combine analytics with intuition. You will never have all the data to decide analytically. Invoke the 80/20 rule.

The litmus test of leaders who have developed a full set of paradox management skills is how they manage the contradiction of valuing people versus valuing performance. Most organizations give both top priority. But if you always value one, how do you always value the other? In particular, when do you remain loyal to people and when do you let them go or decide you can give them the promotion they want? How do you resolve the case of a person who no longer fits or performs?

Here are two stories to illustrate the difficulty:

• Danielle is an executive with a large corporation, and people love to work for her. She sticks by and sticks up for her people under almost every circumstance. Everyone knows that she is fair, goes out of her way to help her people learn and grow, and has empathy to spare. Yet Danielle also is incapable of getting rid of the deadwood on her team, of which she has accumulated plenty over the years. She accepts every excuse in the book for failing to complete an assignment on time or on budget. Consequently, she is a poor implementer—she isn't trusted with getting things done. Her inability to manage the paradox of people and results makes her what we call a Beloved Loser.

• Jack is a senior leader who is loyal to his people to a fault—a major fault. He promotes individuals he is closest to, regardless of whether their abilities and achievements make them right for positions of increased responsibility. At the same time, he champions meritocracy. He lobbies HR for a better system that rewards talent rather than seniority, yet he fails to see how he doesn't walk the talk. The paradox of loyalty versus fairness escapes him. For this reason, he is what we call a Hypocrite; even the people to whom he is loyal and promotes see him that way.

Leaders who fall into the category of Beloved Loser and Hypocrite have not learned how to manage paradoxes. They must understand the forces they are trying to reconcile and make decisions that show they are able to work through these types of contradictions.

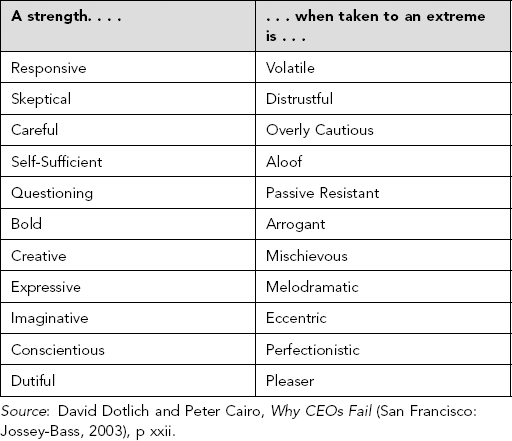

Overcoming Derailers

Among the most personally sensitive aspects of self-development as a paradox leader is learning to overcome derailers, the obstacles mentioned in Chapter Three. Under stress, we all can express destructive behaviors that undermine our effectiveness and sabotage our aspirations. Instead of exhibiting calm and steadiness under pressure, we become volatile and overreact to the slightest setback. Instead of appropriately challenging people's suggestions, we become distrustful and suspicious of their motives. Instead of being careful, we become overly cautious and hesitant to make any decision when an action is called for. See Table 12.1.

Derailers are not learned behaviors. They are ingrained personality traits. You're stuck with them. When stress rises, when anxiety hits a threshold, the impulses from your lesser self overpower the impulses from your more rational, mature, and relaxed self. You screw up, and you may not even realize you've done it. But those around you, whether your loved ones or your business colleagues, observe the derailment as clearly as a train going off the tracks. Your constructive behavioral train vanishes into an abyss, and it takes the passengers with it. Your colleagues, your reports, your family—they all get tossed around in the derailment.

Ron clearly exhibited one of the derailers: arrogance. This is a common one among hard-charging, competitive people. If you're one of them, you may recall times that, under stress, you let your natural confidence go over the edge to become hubris. In Ron's case, he required feedback to become acutely aware of the need to be more inclusive and open. He moderated his overweening style, determining when to push his own ideas and when to exercise patience in bringing people along. By loosening his control and extending trust to his people, he became more effective.

Table 12.1. Leadership Strengths and Derailers

In our coaching work, we run across people with the full selection of potential derailers, which show up both in their work and in their personal life. As another example, consider the case of Allison, a top operations executive at a global consumer brands company. Allison (introduced in Chapter Nine) had long run an operating division. She took satisfaction in delivering ever-better results, higher sales, better profits, and a solid pipeline of product improvements. If you gave her a defined task over a short period, she delivered every time. She was a star.

But Allison's boss moved her to a new job. As head of global branding, she became responsible for guiding, protecting, and strengthening the brand around the world. This took her from a world with few paradoxical problems to one full of them, a world where she often struggled with marketing directors and division presidents with demands to change products in ways contradictory to the global brand promise. Prompted by the added complexity and ambiguity, her stress and anxiety levels spiked, and her key derailer—being overly cautious—began to take a toll. To every new proposal, she would say, “yes, but. . . .” For instance, the company had suffered a disastrous product launch in a new market five years earlier, and she would not agree to entertain a proposal in that market again. Her fear of failure started to overwhelm her ability to lead.

If you're caught derailing for this or another reason, what do you do? For most people, rehabilitation starts with awareness. Once you realize that you have a derailer or two—everybody does—you can build into yourself a sort of alarm system that starts flashing its lights and blaring its horn when you react to a paradox in a destructive way. Becoming aware, in some ways, is an easy first step, even though you—like Ron and Allison—may have to have someone help you. The next step is to acknowledge and accept the derailers. They are, after all, who you are. This can be hard, because the derailers are often strengths taken to an extreme—volatility, for example, is essentially responsiveness and enthusiasm on steroids.

But taking this step is easier when you know you're in good company: Everyone has a shadow side. Counterintuitively, acknowledging weaknesses and vulnerabilities, along with pinpointing how they hurt our effectiveness, actually makes us stronger in the eyes of others. After all, our colleagues and family already know what our derailers are. Only the act of admitting them may surprise people, since the nature of the derailers will be old news. We had one leader return home from learning about his derailers in one of our workshops, agog with his new insight, and his wife said, “I could have told you that over a cup of coffee.”

Self-knowledge gives us authority and credibility—in addition to better ability to manage paradoxes. We may have a cherished self-image. But we need to have compassion for ourselves and the vulnerabilities we wish we didn't have—and then embrace a modified, more vulnerable self-image.

Another key to managing derailers is knowing when they emerge. People differ in what stresses them. Some people have difficulty dealing with workload and deadlines. Some get overly anxious when they face a huge decision. Others have trouble working with people in authority. Still others react badly in the face of interpersonal conflict. Leaders need to know what their own hot buttons are and what situations push them over the edge before they can develop strategies for preventing derailment.

As another example, we coached the CEO of a large retail chain. He was a smart, highly analytical executive who loved data. His ability to absorb huge amounts of data and devise winning strategies had enabled him to turn around several companies. But he took his data hunger to an extreme, and it became a derailer of a special kind: His people feared approaching him without being prepared with encyclopedic detail, combat-ready for an intellectual competition with the boss. His people started to develop a sort of bunker mentality, which he regularly reinforced by telegraphing them the clear message: “You can never have enough data.”

We introduced him to this derailer, and although he couldn't change his personality, we suggested he add new behaviors to mitigate his weakness and stop paralyzing the action of his staff. At a staff meeting, he opened up to his people: “I am more and more aware that my style may be hurting our effectiveness,” he said. “I'm conscious that I overanalyze things to the point that you spend too much time preparing for me and too little time acting with your team. Tell me how you experience my behavior, and point out to me next time we meet the effects it has on you. I don't know how I should change, but I'd like to go on a journey with you to make myself better.”

This was a remarkable multi-step process of acknowledgment, acceptance, and pinpointing how the derailer hurt other people. Two months later, his people said they were seeing a change. His initiative in asking for feedback on his behavior was, again ironically, helping him build his reputation as a leader. The parallels to your personal life are probably plain. You grow in the eyes of others as a strong human as you grow in self-knowledge, acceptance, and skillfulness as a collaborator.

Allison's development traveled along a similar path. With a better idea of her weaknesses and the knowledge that she could sabotage her own success, she positioned herself to push innovation rather than suppress it. She created special forums focused specifically on innovation, and she invited the company's best thinkers and outside experts to engage in open dialogue about extending product lines, discovering new products, and entering new markets.

Sometimes, in the case of overly cautious people, we simply ask, “What are you afraid of?” Or “What's the worst that can happen?” We then explore the consequences of not acting. In the end, leaders like Allison learn to recognize both assets and liabilities, which frees them to build on the assets and mitigate the liabilities. That's what Ron did—and he earned the rewards not only in helping the company deliver better results but in helping himself become a congenial colleague.

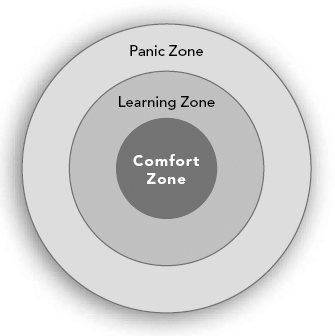

As an aside, note that stress doesn't just trigger derailers. It creates a barrier to raising people's consciousness of paradoxical problems in the first place. Because people face so many demands today, many leaders operate for days on end feeling overwhelmed. Their feet are held to the fire to achieve ambitious objectives, and at first glance, they think that managing paradoxes is tangential to their main work—especially for newer leaders who are less aware of paradox than more senior ones. When you talk to them about learning to manage paradox, they may look at you like you're oblivious to all the stress they're under. As Figure 12.1 shows, there is a fine line between learning and stress. You need to stay below the line, lest derailers get the better of you.

Overcoming Hindrances to Action

Learning to manage yourself as a paradox leader also means understanding your mental barriers to taking action—barriers that persist even after you make a decision. Some of these barriers are none other than derailers. A prolonged search for perfection, for example, can lull you into putting off action for months. A fear of failure or an excessive focus on what could go wrong, as in Allison's case, can become an unlimited excuse for delay. And the need to please others and avoid conflict can bring action to a standstill. By dealing with these derailers, you can help prevent them—and not just keep them from bringing things to a halt.

Figure 12.1. MSThe Fine Line Between Learning and Derailing

Source: Reldan Nadler and John L. Luckner, Processing the Experience: Strategies to Enhance and Generalize Learning, 2nd ed. (Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt, 1997), 418.

The danger of decision deferral is greater than it seems. The risk is not only that you will lose the time spent dithering. You will fail to act altogether. Research confirms something we all learn from experience: The more we put something off, the less likely we are to do it at all. A now classic experiment by psychologists Amos Tversky and Eldar Shafir demonstrated in the 1990s that, in effect, haste prevents waste (or at least timeliness does). They offered three groups of nearly sixty students each either five days to complete a questionnaire, three weeks, or no time limit. In return each student would earn $5. Sixty percent of the five-day group responded, but only 42 percent of the three-week group—and just 25 percent of the indefinite group. The students were being offered easy money, but as Tversky and Shafir wrote, “Many things never get done not because someone has chosen not to do them, but because the person has chosen not to do them now.”3

More recent research by a group of German researchers modeled data from a consumer survey of the German cell phone market. Consumers in this market were offered more than seven hundred plan options (of phones, fees, services, and price structures). The study looked at the effects of number, complexity, and comparability of features on people's behavior. The results revealed the source of consumers' tendency toward paralysis in decision making (that is, not picking a plan, delaying picking a plan, or sticking with the one they already had) as uncertainty over which alternative is best and “anticipated regret,” or worry that you'll kick yourself later for making the wrong decision.4 In our experience, uncertainty and anticipated regret influence not just coming to decisions on consumer choices but acting on paradoxical problems, owing to the much higher level of complexity and ambiguity.

Just knowing about the human tendency to defer decisions can help you get beyond it. We advise leaders to use another aid as well: an expanded circle of trusted advisers. If you keep the responsibility of pushing the start button all to yourself, you may come up short on the confidence to do so. But if you act with the backing of collaborators, you can move ahead more decisively. That said, in today's fast-moving world, you also have to learn to trust your instincts. Often you don't have time for an extra round of data gathering and review, in which case you need to remain mindful of the need to push aside the forces that encourage procrastination.

Along with deferring decisions, people are prone to inaction because of two other common biases. One is the omission bias, whereby people interpret the negative consequences of an event as less harmful if someone did not take (or omitted) action than if someone did take (or committed) action.5 This bias operates even if we are aware of it. One study found that people hesitate to vaccinate a child even when the probability of the child getting the disease far exceeds the probability of death from the vaccine. The authors extrapolated these effects into the business world: “Consider a manager faced with a decision between investing in a new technology and sitting on the sidelines. Research suggests that investing and failing is more risky to the manager's career than failing to invest in a technology that proves successful elsewhere.”6 In both judgments of ourselves and of others, we are harsher when a bad outcome results from doing something than when it results from doing nothing.

Another strong determinant of failure to act is the status quo bias.7 This bias refers to people's natural preference for the current state—when it is included as an alternative—even when they believe it's not necessarily the best choice. In addition to avoiding anticipated regret, psychologists speculate that the status quo bias arises from people's aversion to loss and the comfort they derive from having a familiar state of affairs.8 People might also prefer the status quo because they feel less reason to justify their decision and accept accountability.9 It's easy to recall instances in both work and private life where we stuck with the status quo, even though we somehow knew it wasn't the right alternative. Leaders need to beware of this.

Adding to the complexity of making the right decision is the tendency toward overconfidence. Most people have much greater confidence in their decisions than the facts would suggest. Leaders consistently overestimate their ability to succeed, whether making an acquisition, launching a new product, entering a new market, or picking a new member of their executive team. This tendency, documented like other biases we have mentioned in Daniel Kahneman's Thinking, Fast and Slow, bedevils even the best leaders. This is yet another reason for being inclusive when it comes to bringing others into your decision-making process, testing assumptions, and encouraging people to challenge your point of view.

The lesson is that acting to manage a paradoxical problem demands not just skilled decision making, but the courage—we have been calling it guts—to make things happen. Nobody is programmed to rush out and manage paradoxical problems, given they are so enmeshed in ambiguity. In fact, we could argue that we are actually programmed not to act. In the case of someone like Allison, this demanded that she overcome the programming of derailers as well as biases toward hesitation. Allison was a swift actor when her job was more defined, as when she was handed quarterly targets by the CEO. But when her challenge switched to handling the contradictions inherent in strengthening regional marketing needs at the same time as the global brand, she faltered.

One interesting factor that governs whether we give the final push to acting: General action and inaction goals. Experiments show that when people are primed to act, they often do so. In one set of experiments, people were exposed to a prime (a stimulus outside their awareness) in the form of a word game with either action words (for example, go and active) or inaction words (for example, stop and rest). The experiments were designed to induce actions as diverse as drawing, exercising, and political participation—and they did so, but only for the action group. Other experiments show that people primed with action words become more goal-oriented and more satisfied in completing goals.10 We can infer that leaders play a key role in motivating others to action not only by their behaviors but also by doing nothing more than using action-related words more frequently when they communicate.

We can't help but refer back to a factor from Chapter Three that figures strongly in the hesitation to act displayed by many leaders in public life: the desire to appear consistent. We have argued (along with Emerson) that consistency in action, as opposed to consistency of purpose, can be destructive. The media and politicians, however, seem to assume the opposite. The press lampoons every possible inconsistency by our leaders. This contributes to the erroneous notion that changing your mind is poor leadership. Unfortunately, too few people distinguish between the consistency of purpose Emerson praised and the consistency of action he ridiculed. Leaders in all positions have an obligation to make the case for—and act on—this distinction. Until then, we will be haunted by the corpse of consistency, which discourages us from breaking from the status quo even when the wicked problems plaguing society demand it.

Spreading the Skills of Paradox Management

As you learn to manage yourself as a paradox leader, you owe it to those around you to spread the personal and collaborative skills widely. If you have not created an awareness of paradoxical problems at all managerial levels, right down to first-line supervisors, your people will become ensnared in conflicts without realizing why. They will default to either/or mindsets, and they will make bad decisions. This can turn people into victims and blamers. Confused by complexity and contradictions, people become passive: “There's no way I can win no matter what I do,” they say, and lapse into indecision and inaction. They may also lash out at the company in frustration, blaming management for their bewilderment: “If senior leaders could just get their act together, I wouldn't have this problem; if they could just make things clearer, I could figure out what to do.”

But of course things won't necessarily get clearer, not if it involves the persistent ambiguity of paradox. The only way to assuage hard feelings will be to help people understand that the forces of paradox demand that people value flexibility and open-ended problem solving. This is of course difficult if people remain confounded by the contradictions, angry at the inconsistency, and uncomfortable with the lack of closure.

Recently, in a major global health care products manufacturing company, we worked with a group of fifty high-potential leaders on developing enterprise leadership. We asked them each to describe in advance the enterprise challenges they faced. Their narratives, written independently, all described similar paradoxes. “How can we centralize in order to have the best possible service model at the best possible cost across the globe, while making sure we stay decentralized to bring the best solutions and price to all geographies?” “How can we bring affordable solutions across the lifespan of an individual, and in both developed and developing markets?” “How can we defy gravity and find $30 billion in new growth from new products while maintaining our core business?”

We pointed out to these leaders that these challenges cannot be addressed solely by a CEO or senior team. They require continuous reinvention and innovation by many people down through the organization. In other words, “it takes a village.” It is imperative that leaders use multiple techniques to spread the skill of paradox management to their teams and organizations. This requires sharing the paradoxical challenge, role modeling, transparency, engagement, and training. Senior leaders need to communicate to young leaders the realities of paradoxical problems so developing leaders can grapple with the opposing forces within the safety of a development process.

The training program should follow from the skills and abilities we have already covered. First, if you're top leader, you need to resist the impulse to deny paradox. You can't give in to the naysayers, who will paint your efforts to grapple with paradoxes as too complicated for others to understand or appearing weak and wishy-washy. People often glibly dismiss the existence of paradoxes for the sake of looking smart or decisive. Don't let them.

Second, you need to build and encourage a culture that embraces transparency, diversity, and reflection. As a leader, you need to model behaviors in which you encourage open conversations, include outsiders in discussions, and digest feedback from both inside and outside stakeholders before acting.

Third, you need to foster learning in yourself and others. As one executive told us, “Sometimes my role is education in order to manage paradox. . . . I believe in meeting people where they are and bringing them along. People may not know what they don't know.”

Fourth, you need to reward effective paradox management—give encouragement, bonuses, and raises that reinforce the management of long-term contradictions, not just short-term moves to solve problems of the moment.

Fifth, you need to expand the use of the five tools we have covered: scanning the environment, scenario thinking, stakeholder mapping, dialogue, and conflict management. Most companies use these tools too little, because people see them as soft. But they are the tried-and-true implements in the toolbox of leaders who run high-performance companies that manage paradoxes to their advantage.

Fact is, you can simplify problems full of contradictions to the point where you create black-and-white choices. But that creates a dangerous illusion for employees, as if paradox doesn't exist at all. Instead, you should consider starting a conversation about paradox and keeping it going. Giving it a name—labeling what happens when managers are torn by contradictory forces—is a great starting point for awareness and reflection. It also helps people articulate their concerns in useful terms—so they're talking about managing paradox rather than solving problems.

As an example of the importance of spreading paradox management down through the ranks, consider our work with a major European technology company. After interviewing the top thirty people, we learned that the company faced a common paradox: how to build new businesses while maintaining the old ones. Both new and old demand cash. Both new and old demand management and R&D time and effort. The company was under intense pressure, however, because Chinese competitors had cut its margins from 20 percent to 5 percent. There was no time to lose.

The leaders had tried to refashion sales incentives to get people to sell new products and services, where margins were higher. But many people kept selling the old products, because familiarity made them seem a safer bet. Our advice was this: Don't leave managing the paradox to the people at the top. Educate everyone about paradox and let leaders down through the ranks manage it in the best way for their situation. Today, the company is embedding an understanding and the language of paradox at all levels of the organization. Leaders at all levels realize there is no quick fix to competitive challenges, and they must engage in building a better, more adaptable company that is sustainable over the long term. Customers will then pay more for new forms of value.

Western companies should see paradox management as a strength—the ability to adapt quickly and choose ever-changing ways to manage contradictory forces. True, paradoxes are messy. If you're a fastidious leader, you will be tempted to sweep them under the rug of corporate tidiness. But people in Western companies will be open to do the opposite, giving Western firms one distinct way to compete with growing Chinese competition.

The Complete Paradox Leader

What is the core secret to leading a company, business, or team faced with paradoxes? At the highest level, it means acting with a mixture of head, heart, and guts: Being analytical when you need to. Responding to human feelings and motives when you collaborate. Summoning the courage to act when challenged by both personal hindrances and perpetual ambiguity. This is what the three mindsets and five tools help you do, and this is what makes a complete leader today.

Without this, the analytical guru like Ron will fail. The softhearted people person like Danielle will stagnate. Gutsy autocrats who represent battlefront-style leadership will succeed only on occasion. In today's world, the people who flourish will bring all their paradox-management capacities together, working collaboratively with others to find fresh ways to resolve contradictions in an ever more complex world.

Above all, successful leaders will see paradoxes as opportunities instead of barriers. To be sure, we've all grown up in educational and business institutions that taught us to solve puzzle-like problems. We have learned to know them and master them. We feel comfortable as we take control, exercise consistency, and find closure with such problems. But complete leaders will move with energy beyond tame puzzle-like problems to the wicked paradoxical ones. They will jump over the line to make a difference in a world of uncertainty and ambiguity. They will not retreat from the challenge or give in to feeling depressed by the difficulty.

Of course, paradox management is not an end in itself. It is only a means to an end: Creating a nimble organization, an adaptable organization, an organization that succeeds where others ossify with outdated decision-making capabilities. When you get beyond thinking of paradoxes as illusions, and you master their mysteries with humility and energy, you will see them as the crucible for solving today's hardest problems. Organizations full of paradox leaders—people who can bring mind and heart and guts into problem solving—will be the makers of our future. As Niels Bohr said, “How wonderful that we have met with a paradox. Now we have some hope of making progress.”11