LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

| 6-1 | List and understand the three main categories of payroll fraud |

| 6-2 | Understand the relative cost and frequency of payroll frauds |

| 6-3 | Define a ghost employee |

| 6-4 | List and understand the four steps of making a ghost employee scheme work |

| 6-5 | Understand how separation of duties in payroll and human resources functions can reduce the threat of payroll fraud |

| 6-6 | Be familiar with methods identified in this chapter for preventing and detecting ghost employee schemes |

| 6-7 | List and understand the four ways that employees can obtain authorization for a falsified time card in a manual system |

| 6-8 | Understand the role that payroll controls play in preventing falsified hours and salary schemes |

| 6-9 | Discuss the methods identified in this chapter for preventing and detecting falsified hours and salary schemes |

| 6-10 | Understand how employees commit commission schemes |

| 6-11 | Identify red flags that are typically associated with commission schemes |

| 6-12 | Be familiar with proactive audit tests that can be used to detect various forms of payroll fraud |

CASE STUDY: SAY CHEESE!1

Every once in a while, a person devises a fraud scheme so complex that it is virtually undetectable. Intricate planning allows the person to cheat a company out of millions of dollars with little chance of getting caught.

Jerry Harkanell is no such person.

Harkanell's payroll scheme put only about $1,500 in his pocket before a supervisor detected his fraud, less than half a year after it began.

Harkanell worked as an administrative assistant for a unit of a large San Antonio hospital. His duties consisted mostly of clerical tasks, including the submission of payroll information for the unit.

An exception report for the month of March listed some unusual activity on Harkanell's time sheet. He had posted eight hours that resulted in overtime wages for a particular pay period. The pay period coincided with a time of low occupancy in Harkanell's unit. During times of low occupancy, there is no need for anyone—especially an administrative assistant—to work overtime.

When his supervisor confronted Harkanell about the eight hours, he confessed. He said he posted the time because of financial problems and threats from his wife to leave him. He immediately submitted his resignation, a hospital administrator accepted it, and Jerry Harkanell became a former hospital employee.

The hospital administrator shared the specifics of this incident with Oscar Straine, director of internal auditing for the hospital and a certified fraud examiner.

“Nobody leaves for just eight hours,” Straine said. “There must be a lot more there.”

When Straine delved into the records, he found exactly what he had suspected. Since October of the previous year, Harkanell had been overstating his hours. He had recorded hours that he had not actually worked; he had posted his hours to shifts for which pay was higher; he had reported vacation time as time worked, drawing not only additional pay but extra vacation time, too.

Unfortunately for Harkanell, his method of cheating his employer left a well-marked paper trail. In his administrative role, he collected and submitted the unit's manually prepared time sheets to his supervisor. She signed the time sheets, made copies to retain for her records, and returned them to Harkanell for delivery to the payroll department. Harkanell then altered his original time sheet before he delivered the approved documents to the payroll department. Amazingly, he completed his time sheets in pencil, allowing him simply to erase the old numbers and make changes.

The audit staff compared the supervisor's copies of time sheets with the time sheets on file in the payroll department. Discrepancies between the two stood out. The investigation lasted less than a month. The results revealed that during a twenty-six-week period, Jerry Harkanell defrauded the hospital of $1,570.

Interviews conducted with coworkers and supervisors revealed one detail that might have tipped Harkanell's hand even earlier, had anyone recognized a suspicious act for what it was.

One Friday before payday when Harkanell had the day off, he showed up at the hospital anyway. This was more than a minor inconvenience since he didn't own a car. But Harkanell took the bus to work just so he could personally get the unit's time sheets approved and turned in to payroll. At the time, no one questioned why he didn't simply ask someone to cover for him.

At the completion of the investigation, the hospital filed a claim with the district attorney's office. Evidence consisted of copies of the approved time sheets, copies of the altered time sheets, and affidavits from Harkanell's supervisors.

An assistant district attorney in charge of the case called the hospital shortly after receiving the case. She had uncovered some interesting details about Harkanell's past during a routine background check. A computer search revealed that he had a criminal history and that he was currently on parole. In fact, the assistant district attorney reported, Harkanell had previously been sentenced to life in prison for armed robbery.

The news that the hospital had unknowingly hired a convicted felon distressed Oscar Straine. He discovered that the hospital's ability to conduct thorough background checks on prospective employees was restricted by money and access to records. The hospital routinely checked criminal records in Bexar County (where the hospital is located) and any counties where an applicant reported having a history. But cost and time prohibited the hospital from checking records in all 254 Texas counties, especially when hiring a low-salaried employee like Harkanell.

The complaint against Harkanell went to the grand jury quickly. Straine testified, the grand jury issued an indictment, and a warrant was issued for Harkanell's arrest.

The sheriff's department attempted to locate Harkanell several times, but with no success. He had moved and, not surprisingly, left no forwarding address. The DA's office notified the hospital that Harkanell had disappeared, and that it had no immediate plans to continue the search.

Harkanell remained at large for several months, but luck was on the hospital's side—or, perhaps more accurately, stupidity was on Harkanell's. Just as he had done with his time sheet fraud, he left a clue behind, this time concerning his whereabouts. This was no subtle hint, either. He might as well have mailed the hospital an invitation with a map.

The following January, Straine was talking to a woman in the human resources department who had worked on Jerry Harkanell's original case. Straine called this woman to talk about his continuing concerns over the hospital's inability to do a more thorough background check on prospective hires. During the conversation, the woman asked, “By the way, did you happen to see the paper a few weeks ago?”

“I don't know what you're talking about,” he replied.

“Oh—well, Jerry Harkanell's picture was on the front page of the business section of the Express.”

“You have to be kidding.” But she wasn't.

Straine immediately searched online for a copy of the article. Within minutes, he'd found a story about a nonprofit organization that helps low-income families buy houses with low-interest loans and no down payment.

Right in the middle of the article was a picture, and right in the middle of that picture was Jerry Harkanell. He and his family were sitting on the front porch of the new home the nonprofit group had helped him purchase. The article detailed Harkanell's story, commenting on how hard he had worked to get his house. And though it never mentioned the address, the article contained enough information to pinpoint the location. The Harkanells lived near a new shopping center and across the street from a park. Theirs was the only new house on the block.

It took Straine ten minutes to find the house from his office. He knew the location of the shopping center, and he drove there, then located the park.

Straine said, “It was weird driving up the street with the photograph, and there's his house. We could even identify the design on the front door and match it with the photograph in the newspaper as we drove up the street.”

As soon as he returned to his office, Straine called the assistant district attorney. Harkanell was arrested the next day.

Harkanell appealed for assistance from the nonprofit organization that had helped him buy his house. They agreed to help him—on the condition that he promise to come clean. The organization contacted the hospital's community outreach program to request that the charge be dropped, or at least decreased from a felony to a misdemeanor.

The hospital declined to drop the charge. The nonprofit group pleaded Harkanell's case, pointing out that he had a wife and a sick child who would have to go on welfare if he were convicted of a felony.

Straine made it clear that the hospital would pursue a conviction, whether a felony or a misdemeanor. The hospital's position was that Harkanell should at least have to face a judge. (Later, the assistant district attorney revealed that had Harkanell pleaded guilty to the felony charge, the judge would have sentenced him to twenty-five years.)

While Harkanell continued to try to get the charges dropped, another piece of his past caught up with him. A separate party filed a forgery claim with the district attorney's office. As soon as the nonprofit organization got word of this development, it refused to provide any additional assistance to Harkanell.

A judge sentenced Jerry Harkanell to thirty-five years in prison. Law enforcement officials escorted him from the courtroom directly to a jail cell.

OVERVIEW

Payroll schemes are another form of fraudulent disbursement (see Exhibit 6-1). These schemes are similar to billing schemes in that they are based on a fraudulent claim for payment that causes the victim company to unknowingly make the fraudulent disbursement. In billing schemes, the false claim is usually based on an invoice (coupled, perhaps, with false receiving reports, purchase orders, and purchase authorizations) that shows that the victim organization owes money to a vendor. Payroll schemes are typically based on fraudulent time cards or payroll registers, and they show that the victim organization owes money to one of its employees. In the preceding case study, for example, Jerry Harkanell turned in false time sheets, which caused his employer to overpay his wages.

Payroll Scheme Data from the ACFE 2011 Global Fraud Survey

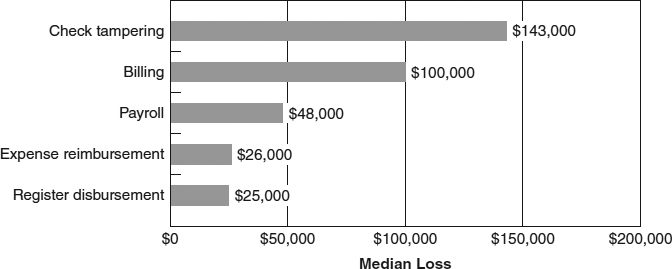

In the ACFE's 2011 survey, payroll schemes ranked fourth among fraudulent disbursements in terms of frequency; one-fifth of the fraudulent disbursement cases reviewed contained some form of payroll fraud (see Exhibit 6-2).

As illustrated in Exhibit 6-3, the median loss among payroll frauds in the 2011 survey was $48,000. Payroll frauds ranked third among fraudulent disbursements in terms of median loss.

PAYROLL SCHEMES

Payroll schemes may be defined as occupational frauds in which a person who works for an organization causes that organization to issue a payment by making false claims for compensation. There are three main categories of payroll fraud:

- Ghost employee schemes

- Falsified hours and salary schemes

- Commission schemes

Ghost Employees

The term ghost employee refers to someone on the payroll who does not actually work for the victim company. The ghost employee may be a fictitious person, or a real individual who simply does not work for the victim employer. When the ghost is a real person, they are often a friend or relative of the perpetrator. In some cases, the ghost employee is an accomplice of the fraudster who cashes the fraudulent paychecks and then splits the money with the perpetrator.

EXHIBIT 6-2 2011 Global Fraud Survey: Frequency of Fraudulent Disbursements*

EXHIBIT 6-3 2011 Global Fraud Survey: Median Loss of Fraudulent Disbursements

Through the falsification of personnel or payroll records, a fraudster causes paychecks to be generated to a ghost; then the paychecks are converted by the fraudster or an accomplice (see Exhibit 6-4). Use of a ghost employee scheme by a fraudster can be like adding a second income to his household.

For a ghost employee scheme to work, four things must happen: (1) the ghost must be added to the payroll, (2) timekeeping and wage rate information must be collected, (3) a paycheck must be issued to the ghost, and (4) the check must be delivered to the perpetrator or an accomplice.

Adding the Ghost to the Payroll The first step in a ghost employee scheme is entering the ghost on the payroll. In some businesses, all hiring is done through a centralized personnel department; in others, the personnel function is spread over the managerial responsibilities of various departments. Regardless of how hiring of new employees is handled within a business, the person or persons who have authority to add new employees are in the best position to put ghosts on the payroll. In Case 2432, for example, a manager who was responsible for hiring and scheduling janitorial work added over eighty ghost employees to his payroll. The ghosts in this case were actual people who worked at other jobs for different companies. The manager filled out time sheets for the fictitious employees and authorized them, then took the resulting paychecks to the ghost employees, who cashed them and split the proceeds with the manager. It was this manager's authority in the hiring and supervision of employees that enabled him to perpetrate this fraud.

EXHIBIT 6-4 Ghost Employees

Another area where the opportunity exists to add ghosts is payroll accounting. In a perfect world, every name listed on an organization's payroll would be verified against personnel records to make sure that those persons receiving paychecks actually work for the company, but in practice this does not always happen. Thus, persons in payroll accounting may be able to generate fraudulent paychecks by adding fictitious employees to the roll. Access to payroll records is usually restricted, so it may be that only managers have access to make changes to payroll accounting records—making these managers the most likely suspects in a ghost employee scheme. On the other hand, lower-level employees often gain access to payroll records, either through poor observance of controls or by surreptitious means. In Case 1042, for instance, an employee in the payroll department was given the authority to enter new employees into the payroll system, make corrections to payroll information, and distribute paychecks. This employee's manager gave rubber-stamp approval to the employee's actions because of a trusting relationship between the two. The lack of separation of duties and the absence of review made it simple for the culprit to add a fictitious employee into the payroll system.

One way to help conceal the presence of a ghost on the payroll is to create a fictitious employee with a name very similar to that of a real employee. The name on the fraudulent paycheck, then, will appear to be legitimate to anyone who glances at it. The perpetrator of Case 970, a bookkeeper who made off with $35,000 in fraudulent wages, used this method.

Instead of adding new names to the payroll, some employees undertake ghost employee schemes by failing to remove the names of terminated employees. Paychecks to the terminated employee continue to be generated even though he no longer works for the victim company. The perpetrator intercepts these fraudulent paychecks and converts them to his own use. For instance, in Case 1738, an accountant delayed the submission of resignation notices of certain employees, and then she falsified time sheets for these employees to make it appear that they still worked for the victim company. This accountant was also in charge of distributing paychecks to all employees of the company, so when the fraudulent checks were generated, she simply took them out of the stack of legitimate checks and kept them for herself.

Collecting Timekeeping Information The second thing that must occur in order for a paycheck to be issued to a ghost employee, at least in the case of hourly employees, is the collection and computation of timekeeping information. The perpetrator must provide payroll accounting with a time card or other instrument showing how many hours the fictitious employee worked over the most recent pay period. This information, along with the wage rate information contained in personnel or payroll files, will be used to compute the amount of the fraudulent paycheck.

Timekeeping records can be maintained in a variety of ways. In many organizations, computer systems are used to track employees' hours. Alternatively, employees might manually record their hours on time cards or might punch time clocks that record the time at which a person starts and finishes his work.

When a ghost employee scheme is in place, someone must create documentation for the ghost's hours. This essentially amounts to preparing a fake time card showing when the ghost was allegedly present at work. Depending on the normal procedure for recording hours, a fraudster might log into the computerized system and record the ghost employee's hours, create a time card and sign it in the ghost's name, punch the time clock for the ghost, or so on. The preparing of the time card is not a great obstacle to the perpetrator. The real key to the timekeeping document is obtaining approval of the time card.

A supervisor should approve time cards of hourly employees. This verifies to the payroll department that the employee actually worked the hours that are claimed on the card. A ghost employee, by definition, does not work for the victim company, so approval will have to be fraudulently obtained. Often, the supervisor himself is the one who creates the ghost. When this is the case, the supervisor fills out a time card in the name of the ghost and then affixes his approval. The time card is thereby authenticated, and a paycheck will be issued. When a nonsupervisor is committing a ghost employee scheme, he will typically forge the necessary approval and then forward the bogus time card directly to payroll accounting, bypassing his supervisor.

In computerized systems, a supervisor's signature might not be required. In lieu of the signature, the supervisor inputs data into the payroll system, and the use of his password serves to authorize the entry. If an employee has access to the supervisor's password, he can input any data he wants, and it arrives in the payroll system with a seal of approval.

If the fraudster creates ghost employees who are salaried rather than hourly employees, it is not necessary to collect timekeeping information; salaried employees are paid a certain amount each pay period regardless of how many hours they work. Because the timekeeping function can be avoided, it may be easy for a fraudster to create a ghost employee who works on salary. However, salaried employees typically are fewer and are more likely to be members of management; the salaried ghost may therefore be more difficult to conceal.

Issuing the Ghost's Paycheck Once a ghost is entered on the payroll and his time card has been approved, the third step in the scheme is the actual issuance of the paycheck. The heart of a ghost employee scheme is in the falsification of payroll records and timekeeping information. Once this falsification has occurred, the perpetrator does not generally take an active role in the issuance of the check. The payroll department issues the payment—based on the bogus information provided by the fraudster—as it would any other paycheck.

Delivery of the Paycheck The final step in a ghost employee scheme is the distribution of the checks to the perpetrator. Paychecks might be hand delivered to employees while at work, mailed to employees at their home addresses, or direct-deposited into the employees' bank accounts. If employees are paid in currency rather than by check, the distribution is almost always conducted in person and on-site.

Ideally, those in charge of payroll distribution should not have a hand in any of the other functions of the payroll cycle. For instance, the person who enters new employees in the payroll system should not be allowed to distribute paychecks because, as in Case 1738, this person can include a ghost on the payroll, then simply remove the fraudulent check from the stack of legitimate paychecks she handles as she disburses pay. Obviously, when the perpetrator of a ghost employee scheme is allowed to mail checks to employees or pass them out at work, he is in the best position to ensure that the ghost's check is delivered to himself.

In most instances, the perpetrator does not have the authority to distribute paychecks, and so must make sure that the victim employer sends the checks to a place from which he can recover them. When checks are not distributed in the workplace, they are either mailed to employees or deposited directly into those employees' accounts.

If the fictitious employee was added into the payroll or personnel records by the fraudster, the problem of distribution is usually minor. When the ghost's employment information is input, the perpetrator simply lists an address or bank account to which the payments can be sent. In the case of purely fictitious ghost employees, the address is often the perpetrator's own (the same goes for bank accounts). The fact that two employees (the perpetrator and the ghost) are receiving payments at the same destination may indicate that fraud is afoot. Some fraudsters avoid this problem by having payments sent to a post office box or to a separate bank account. In Case 1042, for example, the perpetrator set up a fake bank account in the name of a fictitious employee and arranged for paychecks to be deposited directly into this account.

As we have said, the ghost is not always a fictitious person; it may instead be a real person who is conspiring with the perpetrator to defraud the company. In Case 687, for instance, an employee listed both his wife and his girlfriend on the company payroll. When real persons conspiring with the fraudster are falsely included on the payroll, the perpetrator typically sees to it that checks are sent to the homes or bank accounts of these persons, in this way avoiding the problem of duplicating addresses on the payroll.

Distribution is a more difficult problem when the ghost is a former employee who was simply not removed from the payroll. In Case 146, for instance, a supervisor continued to submit time cards for employees who had been terminated. Payroll records will obviously reflect the bank account number or address of the terminated employee in this situation. The perpetrator, then, has two courses of action. In companies where paychecks are distributed by hand or are left at a central spot for employees to collect, the perpetrator can ignore the payroll records and simply pick up the fraudulent paychecks. If the paychecks are to be distributed through the mail or by direct deposit, the perpetrator will have to enter the terminated employee's records and change his delivery information.

Preventing and Detecting Ghost Employee Schemes It is very important to separate the hiring function from other duties associated with payroll. Most ghost employee schemes succeed when the perpetrator has the authority to add employees to the payroll and approve the time cards of those employees; it therefore follows that if all hiring is done through a centralized human resources department, an organization can substantially limit its exposure to ghost employee schemes.

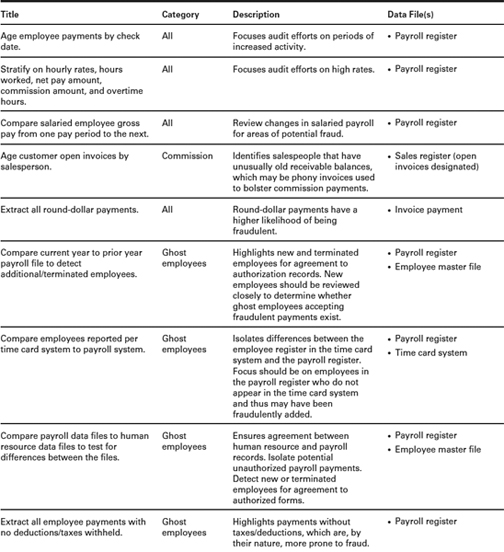

Personnel records should be maintained independently of payroll and timekeeping functions, and the personnel department should verify any changes to payroll. The personnel department should also conduct background checks and reference checks on all prospective employees in advance of hire. These simple verification procedures should eliminate most ghost employee schemes by making it impossible for a single individual to add a ghost to an organization's payroll. If employees know that payroll changes are verified against personnel records, this will deter most ghost employee schemes. Furthermore, if personnel and payroll records are maintained separately, a simple comparison report should identify persons on the payroll who have no personnel file. Organizations should also periodically check the payroll against personnel records for terminated employees and unauthorized wage or deduction adjustments.

Another way to proactively test for ghost employees is to have someone in the organization who is independent of the payroll function periodically run a report looking for employees who lack Social Security numbers, who have no deductions on their paychecks for withholding taxes or insurance, or who show no physical address or phone number. Fraudsters who create ghost employees often fail to attend to these details, the omission of which is a clear red flag. Similarly, reports should be run periodically looking for multiple employees who share a Social Security number, bank account number, or physical address. All these conditions tend to indicate the presence of a ghost on the payroll.

A comparison of payroll expenses to production schedules might also uncover a ghost employee scheme. The distribution of hours to activity or departments should be reviewed by supervisors in those departments, and payroll expenses should be compared to budgeted amounts. Significant budget overruns could signal payroll fraud.

Finally, by simply keeping signed paychecks in a secure location, and by verifying that they are properly distributed, an organization can thwart most ghost employee schemes. The employee or manager who adds a ghost to the payroll must be able to collect the ghost's check. In most cases, he is able to do that because he has access to payroll checks prior to distribution, or because he is in charge of distributing paychecks himself. If an organization assigns the task of distributing paychecks to a person who is independent of the payroll functions and who has no authority to add personnel, this can make it difficult for the perpetrator to obtain the ghost's paycheck. The duty of distributing paychecks should be rotated among several employees to further guard against fraud. Employees should be required to provide identification to receive their paychecks to ensure that every employee receives only his own check, and if pay is deposited directly into bank accounts, a report should be run every pay period searching for multiple employees who share an account number.

Falsified Hours and Salary

The most common method of misappropriating funds from the payroll is through the overpayment of wages. For hourly employees, the size of a paycheck is based on two essential factors: the number of hours worked, and the rate of pay. It is therefore obvious that for an hourly employee to fraudulently increase the size of his paycheck, he must either falsify the number of hours he has worked or change his wage rate (see Exhibit 6-5). Because salaried employees do not receive compensation based on their time at work, in most cases these employees generate fraudulent wages by increasing their rates of pay.

When we discuss payroll frauds that involve overstated hours, we must first understand how an employee's time at work is recorded. As we have already discussed, time is generally kept by one of three methods. Time clocks may be used to mark the time when an employee begins and finishes work. The employee inserts a card into the clock at the beginning and end of work, and the clock imprints the current time on the card. In more sophisticated systems, computers may automatically track the time employees spend on the job based on login codes or some other similar tracking mechanism. Finally, paper or computerized time cards showing the number of hours an employee worked on a particular day are often prepared manually by the employee and approved by his manager.

Manually Prepared Time Cards When hours are recorded manually, an employee typically fills out his time card to reflect the number of hours he has worked and then presents it to his supervisor for approval. The supervisor verifies the accuracy of the time card, signs or otherwise approves the card to indicate his authorization, and then forwards it to the payroll department so that a paycheck can be issued. Most of the payroll frauds we encountered in our studies stemmed from abuses of this process.

Obviously, if an employee fills out his own time card, it may be easy to falsify his hours worked. He simply records the wrong time, showing that he arrived at work earlier or left later than he actually did. The difficulty is not in falsifying the time card, but in getting the fraudulent card approved by the employee's supervisor. There are basically four ways for the employee to obtain the authorization he needs.

Forging a Supervisor's Signature When using this method, an employee typically withholds his paper time card from those being sent to the supervisor for approval, forges the supervisor's signature or initials, and then adds the time card to the stack of authorized cards that are sent to payroll. In an electronic payroll environment, an employee who learns his supervisor's password can log into the system and authorize his own time card surreptitiously. The fraudulent time card then arrives at the payroll department with what appears to be a supervisor's approval, and a paycheck is subsequently issued.

EXHIBIT 6-5 Falsified Hours and Salary

Collusion with a Supervisor The second way to obtain approval of a fraudulent time card is to collude with a supervisor who authorizes timekeeping information. In these schemes, the supervisor knowingly approves false time cards and usually takes a portion of the fraudulent wages. In some cases, the supervisor may take the entire amount of the overpayment. In Case 2406, for example, a supervisor assigned employees to better work areas or better jobs, but in return she demanded payment. The payment was arranged by the falsification of the employees' time cards, which the supervisor authorized. The employees were paid for fictitious overtime, which was then kicked back to the supervisor. It may be particularly difficult to detect payroll fraud when a supervisor colludes with an employee, because managers are often relied on as a control to ensure proper timekeeping.

But in payroll collusion schemes, the supervisor does not always take a cut of the overpayment. Case 749, for instance, involved a temporary employee who added fictitious hours to her time sheet. Rather than get the approval of her direct supervisor, the employee obtained approval from an administrator at another site. The employee was a relative of this administrator, who authorized her overpayment without receiving any compensation for doing so. And in another case, 2314, a supervisor needed to enhance the salary of an employee in order to keep him from leaving for another job. The supervisor authorized the payment of $10,000 in fictitious overtime to the employee. But two part-time employees who did not even bother to show up for work committed perhaps the most unique case in the ACFE studies. One of the fraudsters did not perform any verifiable work for nine months; the other was apparently absent for two years! The time cards for these employees were completed by a timekeeper based on their work schedules, and a supervisor approved the time cards. This supervisor was also a part-time employee who held another job, in which he was supervised by one of the fraudsters. Thus, the supervisor was under pressure to authorize the fraudulent time cards in order to keep his second job.

Rubber Stamp Supervisors The third way to obtain approval of fraudulent time cards is to rely on a supervisor to approve them without reviewing their accuracy. The “lazy manager” method seems risky—so much so that one would think that it would be uncommon—but it actually occurs quite frequently. A recurring theme in ACFE studies is the reliance of fraudsters on the inattentiveness of others. When an employee sees an opportunity to make a little extra money without getting caught, that employee is more likely to be emboldened to attempt a fraud scheme. The fact that a supervisor is known to rubber-stamp time cards, or even ignore them, can be a factor in an employee's decision to begin stealing from his company.

For instance, in Case 1615 a temporary employee noticed that his manager did not reconcile the expense journal on a monthly basis. Thus, the manager did not know how much was being paid to the temporary agency. The fraudster completed fictitious time reports that were sent to the temporary agency and that caused the victim company to pay over $30,000 in fraudulent wages. Because the fraudster controlled the mail and the manager did not review the expense journal, this extremely simple scheme went undetected for some time. In another example of poor supervision, Case 503, a bookkeeper whose duties included the preparation of payroll checks, inflated her checks by adding fictitious overtime. This person added over $90,000 of unauthorized pay to her wages over a four-year period before an accountant noticed the overpayments.

Poor Custody Procedures One form of control breakdown that occurred in several cases in our studies was the failure to maintain proper control over authorized time cards. In a properly run system, once management authorizes time cards, they should be sent directly to payroll. Those who prepare the time cards should not have access to them after they have been approved. Similarly, computerized time sheets should be blocked from modification by the employee once supervisor authorization has been given. When these procedures are not observed, the person who prepared a time card can alter it after his supervisor has approved it but before it is delivered to payroll. This is precisely what happened in several cases in our studies. In the case study at the beginning of this chapter, for instance, Jerry Harkanell was in charge of compiling weekly time sheets (including his own), obtaining his supervisor's approval on the sheets, and delivering the approved sheets to payroll. As we saw, Harkanell waited until his supervisor signed the unit's time sheets, then overstated his hours or posted hours he had worked to higher-paid shifts. Since the supervisor had authorized the time sheet, payroll assumed that the hours were legitimate.

Another way hours are falsified is in the misreporting of leave time. This is not as common as time card falsification, but nevertheless can be problematic. Incidentally, it is the one instance in which salaried employees commit payroll fraud by falsifying their hours.

The way a leave scheme works is very simple. An employee takes a certain amount of time off of work as paid leave or vacation, but does not report the absence. Employees typically receive a certain amount of paid leave per year. If a person takes a leave of absence but does not report it, those days are not deducted from his allotted days off. In other words, he gets more leave time than he is entitled to. The result is that the employee shows up for work less, yet still receives the same pay. This was another method used by Jerry Harkanell to increase his pay. Another example of this type of scheme was found in Case 1315, where a senior manager allowed certain persons to be absent from work without submitting leave forms to the personnel department. Consequently, these employees were able to take excess leave amounting to approximately $25,000 worth of unearned wages.

Time Clocks and Other Automated Timekeeping Systems In companies that use time clocks to collect timekeeping information, payroll fraud is usually uncomplicated. In the typical scenario, the time clock is located in an unrestricted area, and a time card for each employee is kept nearby. The employees insert their time cards into the time clock at the beginning and end of their shifts and the clock imprints the time. The length of time an employee spends at work is thus recorded. Supervisors should be present at the beginning and end of shifts to ensure that employees do not punch the time cards of absent coworkers, yet this simple control is often overlooked.

AFCE researchers encountered very few time clock fraud schemes, and those they did come across followed a single, uncomplicated pattern. When one employee is absent, a friend of that person punches his time card so that it appears as if the absent employee was at work that day. The absent employee is therefore overcompensated on his next paycheck. This method was used in Cases 478 and 2673.

Rates of Pay While the preceding discussion focused on how employees overstate the number of hours they have worked, it should be remembered that an employee could also generate a larger paycheck by changing his pay rate. An employee's personnel or payroll records reflect his rate of pay. If an employee can gain access to these records, or has an accomplice with access to them, he can adjust the pay rate to increase his compensation.

Preventing and Detecting Falsified Hours and Salary Schemes As with most other forms of occupational fraud, falsified hours and salaries schemes generally succeed because an organization fails to enforce proper controls. As a rule, payroll preparation, authorization, distribution, and reconciliation should be strictly segregated. In addition, the transfer of funds from general accounts to payroll accounts should be handled independently of the other functions. This will prevent most instances of falsified hours and salary schemes.

The role of the manager in verifying hours worked and authorizing time cards is critical to preventing and detecting this form of payroll fraud. Organizations should have a rule stating that no overtime will be paid unless a supervisor authorizes it in advance. This control is not only a good antifraud mechanism, it is also key to maintaining control over payroll costs. Sick leave and vacation time should also not be granted without a supervisor's review. Leave and vacation time should be monitored for excesses by an independent human resources department.

A designated official should verify all wage rate changes. These changes should be administered through a centralized human resources department. Any wage rate change not properly authorized by a supervisor and recorded by human resources should be denied.

After a supervisor has approved time cards for her employees, those time cards should be sent directly to the payroll department, and employees should not have access to their time cards after they have been approved. One of the most common falsified hours and salary schemes is to simply alter a time card after it has been approved. Maintaining proper custody of approved time cards will go a long way toward eliminating this type of fraud.

If a time clock is used, time cards should be secured and a supervisor should be present whenever time cards are punched. This supervisor should work independently of hiring and other payroll functions. A different supervisor should approve time cards.

In addition to controls aimed at preventing payroll fraud, organizations should run tests that actively seek out fraudulent payroll activity. For example, in a document-based system, supervisors should maintain copies of their employees' time cards. These copies can be spot-checked against a payroll distribution list or against time cards on file in the payroll department. Any discrepancies likely indicate fraud. In an electronic environment, tests should be run to determine whether any time cards were accessed or altered after the supervisor's approval; exceptions should be confirmed with the approving supervisor for legitimacy.

Because many falsified hours and salary schemes involve fraudulent claims for overtime pay, organizations should actively test for overtime abuses. Comparison reports can illustrate instances in which a particular individual has been paid significantly more overtime than other employees who have similar job duties or in which a particular department tends to generate more overtime expenses than are warranted. Other tests that can highlight falsified hours and salary schemes include the following:

- Perform a trend analysis comparing payroll expenses to budget projections or prior years' totals. This analysis can be done by company or by department.

- Generate exception reports testing for any employee whose compensation has increased from the prior year by a disproportionately large percentage. For example, if an organization generally awards raises of no more than 3 percent, then it would be advisable to double-check the records of any employee whose wages have increased by more than 3 percent.

- Verify that payroll taxes for the year equal federal tax forms.

- Compare net payroll to payroll checks issued.

Commission Schemes

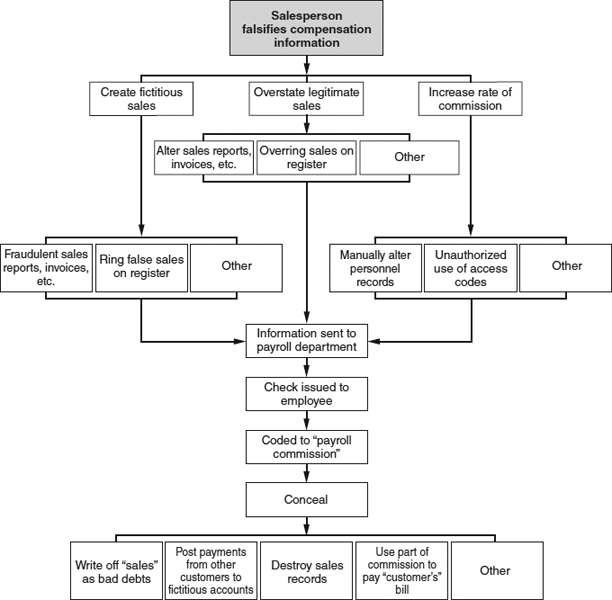

Commission is a form of compensation calculated as a percentage of the amount of sales a salesperson or other employee generates. It is a unique form of compensation that is not based on hours worked or a set yearly salary, but rather on an employee's revenue output. A commissioned employee's wages are based on two factors: the amount of sales he generates and the percentage of those sales he is paid. In other words, there are two ways an employee on commission can fraudulently increase his pay: (1) falsify the amount of sales made or (2) increase his rate of commission (see Exhibit 6-6).

Fictitious Sales An employee can falsify the amount of sales he has made in two ways, the first being the creation of fictitious sales. In Case 531, for example, an unscrupulous insurance agent took advantage of his company's incentive commissions, which paid $1.25 for every $1.00 of premiums generated in the first year of a policy. The agent wrote policies to fictitious customers, paid the premiums, and received his commissions, which created an illicit profit on the transaction. For instance, if the fraudster paid $100,000 in premiums, he received $125,000 in commissions, a $25,000 profit. No payments were made on the fraudulent policies after the first year.

EXHIBIT 6-6 Commission Schemes

The way in which fictitious sales are created depends on the organization for which the fraudster works. A fictitious sale might be constructed by the creation of fraudulent sales orders, purchase orders, credit authorizations, packing slips, invoices, and so on. On the other hand, a fraudster might simply ring up a false sale on a cash register. The key is that a fictitious sale is created, that it appears to be legitimate, and that the victim company reacts by issuing a commission check to the fraudster.

Altered Sales The second way for a fraudster to falsify the value of sales he has made is to alter the prices listed on sales documents; in other words, the fraudster charges one price to a customer, but records a higher price in the company books. This results in the payment of a commission that is larger than the fraudster deserves. Case 1681 provides an example of this type of scheme. In this situation a salesman quoted a certain rate to his customers, and billed them at this rate and collected their payments—but overstated his sales reports. The fraudster intercepted and altered the outgoing invoices from these transactions so that his customers would not detect the fraud. He also overstated the revenues received from his customers. Since the fraudster's commissions were based on the amount of revenues he billed out, he was overcompensated.

As mentioned above, the other way to manipulate the commission process is to change the employee's rate of commission, This would likely necessitate the alteration of payroll or personnel records, which should be off-limits to the sales staff.

Detecting Commission Schemes Generally, there should be a linear correlation between sales figures and commission expenses. Periodic reports should be run to confirm this relationship. If commission expenses increase as a percentage of total sales, this might indicate fraud. An employee who is independent of the sales department should investigate the reason for the increase.

If a salesperson is engaged in a commission scheme, his commissions earned will tend to rise compared to other members of the sales department. Organizations should routinely test for this type of fraud by running a comparative analysis of commission earned by each salesperson, verifying rates and calculation accuracy.

In addition, organizations should track uncollected sales generated by each member of their sales department. One of the most common commission schemes involves the creation of fictitious sales to bolster commission earnings. Obviously, these fictitious sales will most likely go uncollected. Therefore, if an employee tends to generate a much higher percentage of uncollected sales than his coworkers, this could indicate fraud. A review of the support for the uncollected sales should be conducted to verify that they were legitimate transactions.

Overstated sales or fictitious sales can also be detected by conducting a random sample of customers. Verify that the customer exists, that the sale is legitimate, and that the amount of the sale corresponds to the customer's records. Someone independent of the sales force must perform this confirmation.

CASE STUDY: THE ALL-AMERICAN GIRL2

If you put 100 people in a room and asked them to pick out the criminal, chances are about 99 other people would get selected before anybody would think to point a finger at Katie Jordan. At about five feet, three inches, with short blonde hair and a bubbly personality, looking barely old enough to be out of high school—much less college—Katie seemed to personify the image of the all-American Girl Next Door. But somewhere along the way, Katie made a bad choice, and that led to another bad choice—and on and on until things had spiraled out of control. Before anybody knew what had happened, Katie Jordan had taken over $65,000 from her employer.

Susan Evers, the CFE who investigated Katie Jordan's case, says the incident was typical of many occupational frauds she encounters, in which “a person starts stealing because they're in a bad spot financially, and they think it's just temporary.” But of course, it rarely is. “They may think they'll pay back the money, but they never do. Usually, before they know it they've taken so much there's no way they could ever pay it all back.”

When Katie Jordan began working for Aramis Properties, she had no intention of defrauding the company. It was her first job out of college, and she was excited about the opportunity, eager to do a good job and move up. And that's what she did. Aramis owned several apartment complexes in the Dallas–Fort Worth area, and Katie was hired as an on-site manager at one of those locations. She showed apartments to prospective tenants, collected rents, oversaw a maintenance crew, and generally ran the day-to-day operations of the complex. She reported to Gil Fleming, who worked in the company's corporate offices and who oversaw several properties, including the one Katie managed. Fleming took a liking to Katie because of her enthusiasm and because she did a good job. “She was very excited about work,” he says. “I never had a single complaint about her performance in any way.”

Katie did such a good job, in fact, that two years later, when the company acquired a large apartment complex in the Houston area, its first property in that market, Gil asked Katie to move to Houston to run it. “Of all the people that worked for me, she was the one I trusted most to do a good job, which is why we sent her,” says Fleming. The new job would leave Katie with very little supervision, since the company's offices were in Dallas and Fleming had little time to travel to Houston to personally oversee her work.

Katie settled into her new job in Houston, and her life pretty much went on as it had before. Things changed, however, when her fiancé suffered an accident. His name was David Green, and in his spare time he was a semiprofessional motocross racer. There wasn't much money in it, and not a lot of security either, but he loved the speed and excitement of the sport. Unfortunately, when he flipped his bike and shattered his leg during a race, he was left hobbled—with no insurance and no income. Money became very tight for David and Katie, who were living together at the time.

Around that same time, one of the employees on the complex maintenance crew, a man named Manuel, quit his job. Under normal circumstances, Katie would have filled out paperwork showing that this employee had left the company and sent it into headquarters, and then she would have begun looking for a replacement. But these were not normal circumstances, and it occurred to Katie that if she did not tell anybody at headquarters that Manuel had quit, then there would be no reason for them to stop issuing his paychecks. So when the next pay period rolled around, Katie collected time sheets for the four employees who worked under her and sent them off to the payroll department in Dallas, just as she always had. But she also filled out a time sheet for Manuel, and included it with the others. Under the company's system, paychecks were mailed back to Katie, who distributed them to the employees. When the paychecks arrived, she took the check made out to Manuel and cashed it at a liquor store.

Suddenly there was some money to help Katie and David get by, and nobody said a word. Every two weeks, she sent in another time sheet for Manuel and received another check. There was no way for anyone who worked at the complex to know what she was doing, because they never saw the books. Nobody at corporate headquarters had any idea, because from their end no changes had been made to the payroll. Gil Fleming visited the site a couple of times, but he never checked to make sure Manuel was still on staff. Why would he? “There was nothing unusual at all,” says Fleming. “Nothing that made us suspect any kind of fraud.”

Eventually Katie had to hire another maintenance man to take up the slack for Manuel's absence. “Her plan had been to float on Manuel's checks for a few weeks to get by,” says Susan Evers, “then she would hire a new maintenance guy and stop taking the checks, and everything would go back to normal.” But when it came time to bring in a new employee, Katie did not want to give up her new source of income. So instead of dropping Manuel off the books, she hired a new employee and kept right on paying Manuel. She even called Fleming at headquarters to let him know she was hiring extra maintenance staff. “She told him there were some problems with the structure, they were getting a lot of repair requests, and she needed the extra help,” says Evers. “He's not there. He trusts her. There wasn't any reason why he wouldn't okay it.”

When Katie saw how easy it was to add an employee, that's when her scheme escalated. “I think that's when she first really figured out how much autonomy she had,” says Evers. “About a month later, she hired an ‘assistant’ to help her at the office. The only problem was, the ‘assistant’ didn't exist.” Katie now had two ghosts on the payroll, Manuel and her new assistant ‘Wendy.’ Between them, they made more than Katie. With very little effort, she'd more than doubled her income.

“The money had originally been for her fiancé, but it got way past that,” says Evers. “Even after she'd taken enough to pay his medical bills, she kept on stealing. She got hooked on the easy money.” It didn't take long before the scheme came unraveled. Katie may have been good at managing apartments, but she was lousy at committing fraud. “She hadn't really thought it through,” says Evers. “The second ghost was supposed to be her assistant, but there wasn't even a desk for her in the office.” Shortly after Wendy went on the books, Fleming made a routine visit to the property. He was standing in the office speaking to Katie and another employee when he casually asked about the new assistant. He immediately knew something was wrong. “The other girl looked confused, and Katie got very flustered,” says Fleming. “Then I started looking around and noticed there was no sign of anybody else working there at all. Then I thought ‘uh oh.’” Katie asked him to come into her office, and she confessed right there. “The whole thing, from the moment I brought it up, took about five minutes,” says Flemming. “She spilled everything and started crying. She told me how sorry she was. Honestly, I think she was relieved to tell me.”

What she didn't tell him was how much she'd stolen. Katie confessed to adding ‘Wendy’ to the payroll, but she said nothing about Manuel. “I don't know why,” says Fleming, “She had to know we'd go back over the books.”

Evers has a theory: “People have a hard time admitting to what they've done. Even when they get caught, they can't admit it was as bad as it really was. They try to downplay it.”

Evers was brought in by the company to go over the books and determine how much Katie had stolen. After reviewing the records and talking to a couple of employees, it didn't take long to figure out that Manuel hadn't worked there in over six months. She also found out that Katie had been skimming rents by taking cash from certain tenants and listing their units as vacant. When she finally interviewed Katie, Evers found out that after the medical bills had been paid off, she had been using the company's funds to pay for her upcoming wedding. She'd bought a dress and put a down payment on a reception hall. She'd also bought a new car.

Katie offered to make good on what she had stolen, but she was only able to pay back about $12,000, less than a fifth of her take. “She was shocked when I told her how much she'd stolen,” says Evers. “She didn't have any idea it was that much, mostly because she didn't want to know. After all, she was the one who was cashing all the checks.”

After Evers filed her report, the company dismissed Katie and pressed charges against her. She was convicted, but served no jail time. Evers also helped the company set up internal controls to provide better checks and balances on the company's accounting and personnel policies. But according to Evers, having strong internal controls is not enough: “Companies have to realize that any employee, under the right circumstances, can commit fraud.” Even an all-American girl.

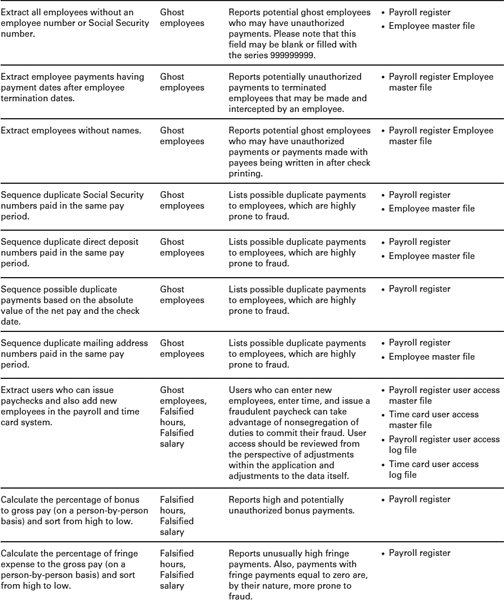

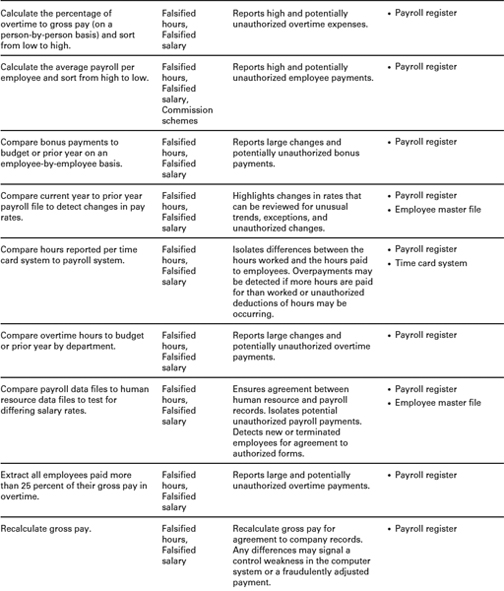

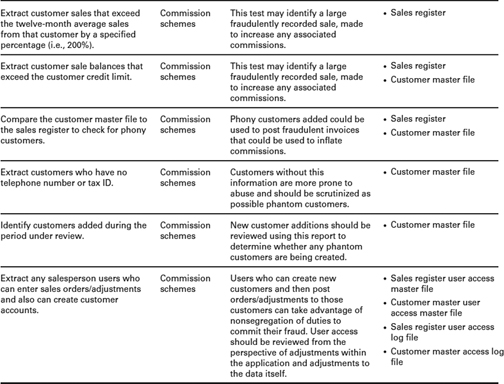

PROACTIVE COMPUTER AUDIT TESTS FOR DETECTING PAYROLL FRAUD1

SUMMARY

Payroll schemes are a form of fraudulent disbursement in which an organization makes a payment to an individual who either works for the organization or claims to work for the organization. Payroll schemes fall into three categories: (1) ghost employees, (2) falsified hours and salary, and (3) commission schemes.

Ghost employees can be either fictitious persons or real persons who do not work for the organization. When the ghost is a real person, they are often a friend or relative of the perpetrator who cashes the fraudulent paychecks and splits the money with the perpetrator.

The most common method of misappropriating funds from the payroll occurs when employees falsify the number of hours they have worked. These schemes usually succeed when organizations fail to segregate the duties of payroll preparation, authorization, distribution, and reconciliation. Corrupt employees can also make unauthorized adjustments to their wage rates to increase the size of their paychecks, though this is not as common as falsifying hours.

Employees who work on commission can defraud a company by falsifying the amount of sales they have made or by falsifying the prices of items they have sold. Salespersons might also change the rate of their commissions to increase their pay.

ESSENTIAL TERMS

Ghost employee An individual on the payroll of a company who does not actually work for the company. This individual can be real or fictitious.

Salaried employees Employees who are paid a set amount of money per period (weekly, biweekly, monthly, etc.). Unlike hourly employees, salaried employees are paid a set amount regardless of the actual number of hours they work.

Rubber stamp supervisor A supervisor who neglects to review documents, such as time cards, before signing or approving them for payment.

Commission A form of compensation calculated as a percentage of the amount of sales an employee generates. A commissioned employee's wages are based on two factors: the amount of sales generated and the percentage of those sales he is paid.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

6-1 (Learning objective 6-1) According to this chapter, what are the three main categories of payroll fraud?

6-2 (Learning objective 6-2) In terms of median losses, which causes larger ones: billing schemes or payroll schemes? Can you offer a possible explanation for why this is so?

6-3 (Learning objective 6-3) What is a “ghost employee”?

6-4 (Learning objective 6-4) Four steps must be completed in order for a ghost employee scheme to be successful. What are they?

6-5 (Learning objective 6-5) Within a given organization, who is the individual most likely to add ghost employees to the payroll system?

6-6 (Learning objective 6-7) The key to a falsified hours scheme in a manual system is for the perpetrator to obtain authorization for the falsified time card. There were four methods identified in this chapter by which employees achieved this. What were they?

6-7 (Learning objectives 6-7 and 6-8) What is meant by the term rubber stamp supervisor, and how are these individuals utilized in a payroll fraud scheme?

6-8 (Learning objective 6-9) List at least three tests that could be performed to detect falsified hours and salary schemes.

6-9 (Learning objective 6-10) There are two ways that an employee working on commission can fraudulently increase his pay. What are they?

DISCUSSION ISSUES

6-1 (Learning objective 6-12) List and explain at least three computer-aided audit tests that can be used to detect a ghost employee scheme.

6-2 (Learning objectives 6-5 and 6-6) The ability to add ghost employees to a company's payroll system is often the result of a breakdown in internal controls. What internal controls prevent an individual from adding fictitious employees to payroll records?

6-3 (Learning objective 6-8) In the case study of Jerry Harkanell, what internal controls could have prevented the falsification of his time sheet?

6-4 (Learning objective 6-8 and 6-9) In terms of preventing payroll fraud, why is it important for hiring and wage rate changes to be administered through a centralized and independent human resources department?

6-5 (Learning objective 6-10) If you suspect that a salesperson is inflating his commissions, what would you do to determine whether this were occurring?

6-6 (Learning objective 6-11) Beta is one of ten salespeople working for ABC Company. Over a given period, 15 percent of Beta's sales are uncollectable, as opposed to an average of 3 percent for the rest of the department. Explain how this fact could be related to a commission scheme by Beta.