EXHIBIT 8-1

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

| 8-1 | Explain what constitutes a register disbursement scheme |

| 8-2 | Differentiate register disbursements from skimming and cash larceny schemes |

| 8-3 | List the two basic categories of register disbursements |

| 8-4 | Explain how false refund schemes are committed |

| 8-5 | Explain how false void schemes are committed |

| 8-6 | Understand how register disbursement schemes cause shrinkage |

| 8-7 | Discuss the methods by which fraudulent register disbursements are concealed |

| 8-8 | Understand the methods identified in this chapter for preventing and detecting register disbursement schemes |

| 8-9 | Be familiar with proactive audit tests that can be used to detect register disbursement schemes |

CASE STUDY: DEMOTION SETS FRAUD IN MOTION1

Following a demotion and consequent pay cut, Bob Walker silently vowed to even the score with his employer. In six months Walker racked up $10,000 in ill-gotten cash from his employer, who was caught completely off-guard, before someone blew the whistle.

The whistleblower was Emily Schlitz, who worked weekends as a backup bookkeeper at a unit of Thrifty PayLess, a chain of 1,000 discount drugstores crossing ten Western states.

One October, while reviewing her store's refund log, Schlitz noticed an unusually large number of protocol breaches by the head cashier—one Bob Walker—who naturally handled most refunds. In issuing cash refunds for big-ticket items, for instance, Walker frequently failed to record the customer's phone number. Often, he neglected to attach sales receipts to the refund log, noting that the customers wanted to keep their receipts. Schlitz questioned the high proportion of these irregularities and notified the store manager, who in turn called the asset protection (security) department at headquarters to investigate what he termed “strange entries.”

Thrifty PayLess pays serious attention to such phone calls, according to its director of asset protection, James Hansen, who celebrated his thirteenth anniversary with the retailer that year. In 57 percent of the fraud cases for that year, Hansen reported, investigators received their first alert directly from store managers, as in this case.

The strange entries that Schlitz found called for immediate action. Hansen dispatched a field investigator, Raymond Willis, to review the findings and conduct a brief background check of Walker—a thirty-two-year-old single male who had been employed by Thrifty PayLess for five years.

Willis soon learned that six months earlier the store manager, citing poor performance, had demoted Walker from a management position to head cashier, which also brought a $300 a month pay cut for Walker. To Willis, that information alone raised some red flags that signal potential fraud by employees: personal or financial problems, lifestyle changes or pressures, and low morale or feelings of resentment.

Further inquiry revealed Walker blamed management for the demotion.

But those red flags paled next to the wealth of evidence Willis uncovered during his investigation. He began by calling customers listed in the refund log to politely inquire about the service they received at the drugstore, discreetly looking for verification or vilification. Next, he compared the number of refunds for food processors—by far the most popular merchandise item Walker accepted for return—to the number originally received in shipment minus those sold. These numbers were in turn compared to the food processors actually in stock. The investigator discovered major discrepancies.

Willis brought the case to a conclusion in just three days. “He stayed awake nights working on this one because he quickly saw the enormity of the take,” recalled boss Hansen. “It just fueled his fire.”

“The perpetrator had really gotten carried away with his activity. As will often happen, over time he got greedy. And once Walker got greedy, he got careless and sloppy,” said Hansen.

Although aggressive in his investigation, Willis kept it quiet. He limited his interviews to just two or three of Walker's fellow employees. “Several coworkers had previously told managers that Walker seemed disgruntled and somewhat upset. But outwardly, his frustration never peaked enough to warrant the need for management to keep an eye on this guy,” explained Hansen.

At the end of Willis's third day in the field, it was time to interview Walker. Initially, Willis asked general questions about store policies and procedures. He went on to focus more on cashiering methods. Walker seemed at ease in the beginning, helpful and responsive. At one point, Walker even offered the suggestion that “more controls should be placed on refunds.”

As the interview progressed, however, Walker got more and more nervous. The smooth talker began to stutter and stammer. Willis asked Walker if he knew the definition of shrinkage. He haltingly replied, “for one, loss of cash or inventory due to customer or employee theft.”

Willis then asked, “What have you personally done to cause shrinkage?” Walker became very quiet. After a long pause, he asked in a hushed tone, “Well, what if I did do it?” Willis laid out the consequences and continued to query the formerly trusted employee.

Walker vented his anger toward the managers who had “unjustly” demoted him. He confessed to writing fake cash refunds in retaliation. While the fraud began in May as an occasional act, it soon increased in frequency and flagrancy. At first, to fulfill the blanks on the customer information part of the refund log, he pulled names at random from the phone book. Later he simply made up names and phone numbers, he said. As his greed escalated, he altered legitimate refunds that he had issued earlier in the day, adding merchandise to inflate their monetary value and pocketing the difference.

Although store policy dictated that management approval was required for refunds totaling more than $25 or in the absence of a sales receipt, Walker deliberately thumbed his nose at those rules and others. No one ever questioned the signature authority of this recently defrocked member of the management team.

To further justify his actions, Walker detailed his previous financial problems, which he said were exacerbated by the $300 monthly pay cut.

Proceeds from the fraud initially went toward his two mortgage payments, which equaled $800 a month. His ongoing booty subsequently financed his insurance premiums and living expenses, which were now mounting. He easily paid off his credit cards. The single man also used the cash for fancy dinners out on the town.

During the two-hour-long confrontation, Walker claimed ignorance about the exact amount he'd filched, saying he had never tallied the score. He did admit, however, that he played this lucrative game with a growing ardor and intensity.

As it turned out, all three refunds Walker had issued the day of the interview proved fraudulent. Yet he still seemed shocked that his fraud totaled upwards of $10,000—more than five-and-a-half times the total pay cut he had endured over the past six months.

In a store that generates $4 million in annual sales, $10,000 over six months represents a small percentage of loss. In the retailing industry, such shrinkage may be explained away by shoplifting, bad checks, accounting or paperwork errors, breakage or spoilage, shipping shortages, or numerous other reasons. Employee theft, of course, is also a significant factor in shrinkage, said Hansen, who began his career as a store detective.

“In my mind, a comprehensive loss prevention program is well balanced between preventive and investigative efforts.” He said Thrifty PayLess maintains an outstanding educational program for all employees. They attend mandated training classes in both the prevention and detection of fraud. Crucial to the success of the antifraud program, employees are always made to feel like an integral part of Thrifty PayLess's whole loss prevention effort. Hansen and his asset protection staff regularly visit the stores to introduce themselves, become familiar to employees, form and maintain rapport, and build a level of trust in confidentiality. To further encourage communication, the retailer established a hotline that employees can call with anonymous tips about suspected fraud or abuse.

As evidenced by the part-time bookkeeper's suspicions and subsequent actions in this case, Thrifty PayLess's efforts obviously work, said the head of security. “It's not that our controls were in any way inadequate; it's that a local manager was not properly enforcing those controls. Generally, he got lax with a ‘trusted’ employee.” (Needless to say, the store manager suffered some repercussions as a result of this case.)

As a result of the Walker experience, manager approval is now required for all refunds over $5. A sales receipt must also accompany all refunds, said Hansen. Thrifty PayLess's internal audit and asset protection departments perform audits regularly, checking for compliance.

“Proper implementation is the key.” Hansen continued. “You cannot prevent fraud 100 percent. The best you can do is to limit it through your proactive educational, awareness, and audit programs. Of course, aggressively investigating all red flags or tips as well.” Hansen's asset protection department concludes over 1,400 employee theft and fraud cases anc 30,000 customer shoplifting cases annually.

Owing to the grand scale of theft in this case, Walker was arrested immediately after his interview, booked on felony charges of embezzlement, and held pending bail. He faced criminal and civil prosecution. Walker made bail within hours, then disappeared without a trace. All investigative efforts to locate him thus far have failed.

To this day Bob Walker remains a fugitive of justice.

OVERVIEW

We have so far discussed two ways in which fraud is committed at the cash register—skimming and cash larceny. These schemes are what we commonly think of as outright theft. They involve the surreptitious removal of money from a cash register. When money is taken from a register in a skimming or larceny scheme, there is no record of the transaction—the money is simply missing.

In this chapter we will discuss fraudulent disbursements at the cash register (see Exhibit 8-1). These schemes differ from the other register frauds in that when money is taken from the cash register, the removal of money is recorded on the register tape. A false transaction is recorded as though it were a legitimate disbursement to justify the removal of money. Bob Walker's fraudulent refunds were an example of such a false transaction.

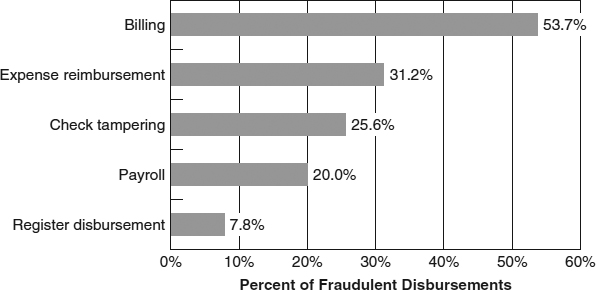

Register Disbursement Data from the ACFE 2011 Global Fraud Survey

Register disbursements were reported less frequently than any other fraudulent disbursement scheme in the 2011 survey; they accounted for less than 8 percent of the reported fraudulent disbursements. It should be remembered, however, that the survey only asked respondents to report one case they had investigated; it was not designed to measure the overall frequency of various types of schemes within a particular organization. Thus, the low response rate for register disbursements does not necessarily reflect how often these schemes occur. Furthermore, the type of fraud that occurs within an organization is, to some extent, determined by the nature of business the organization conducts. For example, register disbursement schemes would tend to be much more common in a large retail store that employs several cash register clerks than in a law firm, where a cash register would not even be present. Readers should keep in mind that the frequency statistics presented in this book only represent the frequency of cases that were reported by the survey respondents (see Exhibit 8-2).

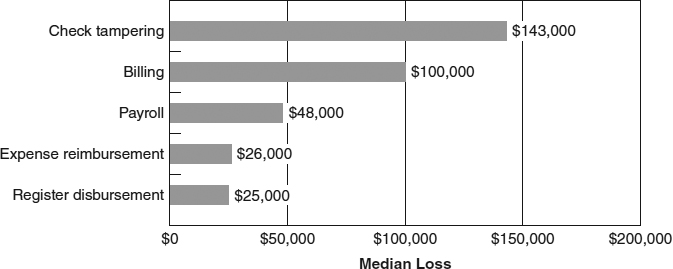

In addition to being the least frequently reported type of fraudulent disbursement, register disbursements were the least costly, with a median loss of $25,000. The typical register disbursement scheme in the survey caused about one-sixth the losses of the typical check tampering scheme (see Exhibit 8-3).

REGISTER DISBURSEMENT SCHEMES

Two basic fraudulent disbursement schemes take place at the cash register: false refunds and false voids. Although these schemes are largely similar, a few differences between the two merit discussing them separately.

EXHIBIT 8-2 2011 Global Fraud Survey. Frequency of Fraudulent Disbursements*

EXHIBIT 8-3 2011 Global Fraud Survey: Median Loss of Fraudulent Disbursements

False Refunds

A refund is processed at the register when a customer returns an item of merchandise purchased from that store. The transaction that is entered on the register indicates that the merchandise is being replaced in the store's inventory and that the purchase price is being returned to the customer. In other words, a refund shows a disbursement of money from the register as the customer gets his money back (see Exhibit 8-4).

Fictitious Refunds In a fictitious refund scheme, a fraudster processes a transaction as if a customer were returning merchandise, even though no actual return takes place. Two things result from this fraudulent transaction. First, the fraudster takes cash from the register in the amount of the false return. Since the register tape shows that a merchandise return has been made, the disbursement appears legitimate. The register tape balances with the amount of money in the register, because the money that was taken by the fraudster is supposed to have been removed, given to a customer as a refund. These kinds of fraudulent transactions were used by Bob Walker in the case study at the beginning of this chapter.

As we also saw in that case study, the second thing that happens in a fictitious refund scheme is that a debit is made to the inventory system showing that the merchandise has been returned to the inventory. Because the transaction is fictitious, no merchandise is actually returned. As a result, the company's inventory is overstated. For instance, in Case 1583, a manager created $5,500 worth of false returns, resulting in a large shortage in the company's inventory. He was able to carry on his scheme for several months, however, because (1) inventory was not counted regularly, and (2) the perpetrator, a manager, was one of the people who performed inventory counts.

Overstated Refunds Rather than create an entirely fictitious refund, some fraudsters merely overstate the amount of a legitimate refund and steal the excess money. This occurred in Case 1875, in which an employee sought to supplement his income by processing fraudulent refunds. In some cases he rang up completely fictitious refunds, making up names and phone numbers for his customers. In other instances he added to the value of legitimate refunds, overstating the value of a real customer's refund, paying the customer the actual amount owed for the returned merchandise, and keeping the excess portion of the return for himself.

Credit Card Refunds When purchases are made with a credit card rather than cash, refunds appear as credits to the customer's credit card rather than as cash disbursements. Some fraudsters process false refunds on credit card sales in lieu of processing a normal cash transaction. One benefit of the credit card method is that the perpetrator does not have to physically take cash from the register and carry it out of the store, the most dangerous part of a typical register scheme (since managers, coworkers, or security cameras may detect the culprit in the process of removing the cash). By processing the refunds to a credit card account, a fraudster reaps an unwarranted financial gain and avoids the potential embarrassment of being caught red-handed taking cash.

In a typical credit card refund scheme, the fraudster rings up a refund on a credit card sale, though the merchandise is not actually being returned. Rather than use the customer's credit card number on the refund, the employee inserts his own. As a result, the cost of the item is credited to the perpetrator's credit card account.

A more creative and wide-ranging application of the credit card refund scheme was used by Joe Anderson in the following case study. Anderson processed merchandise refunds to the accounts of other people and in return received a portion of the refund as a kickback. CFE Russ Rooker discovered Anderson's scheme, which cost Greene's department store at least $150,000. This case is also a bribery scheme, because Anderson took illicit payments in exchange for creating fraudulent transactions. It serves as an excellent example of how the cash register can be used as a tool for theft.

CASE STUDY: A SILENT CRIME2

“A silent crime”—that's the way Russ Rooker refers to the theft he uncovered at a Detroit-area Greene's department store. “It takes only about 30 seconds, and you can have a thousand bucks,” explains the regional investigation specialist.

Joe Anderson, a 15-hour-a-week employee in that store's shoe department, was an expert at that silent crime—ringing up fictitious returns and crediting credit cards for the cash.

During his five-year tenure with the store, Anderson did this time and time again. Rooker documented at least $150,000 in losses, but believes it was closer to $500,000, and wouldn't be surprised if the fraud exceeded $1 million. “We're scared to even know,” he says.

This was a scam that was right up Rooker's analytical alley. At the time of the investigation, he had worked in retail security for about a decade—first as a credit fraud investigator checking the external, or customer, side of credit card fraud. Then he went into internal investigation, searching out employee theft and fraud.

At Greene's store, records showed that the store's shoe department was losing money because it had an exceedingly high rate of returns on its shoes. Rooker decided to investigate by using his “FTM” formula—Follow the Money.

He ordered up five months of sales data for the department from ten sales terminals. Rooker had returns divided into categories of cash, proprietary credit cards (i.e., Greene's cards), and third-party credit cards such as Visa and MasterCard.

And he saw a trend. Around the twenty-eighth of each month, certain credit card numbers would be credited for a return of approximately $300. “Two hundred ninety-seven dollars and sixty cents to be exact,” says Rooker. There was never a corresponding sale recorded for the returns. And each month, each credit card number was credited only once—thus, if Rooker had chosen to study only one month's data, the crime would not have been discovered.

He eventually found that one part-time employee, Joe Anderson, was crediting more than 200 credit cards belonging to 110 persons. Each week, Anderson credited $2,000 to $3,000 in returns to his friends', neighbors', and relatives' accounts. In return, Anderson was paid up to 50 percent of the credit. For instance, if a friend was running $300 short at the end of the month and still needed to make his house payment, he'd phone Anderson. According to Rooker, the word around Detroit was if you needed money, “Call Joe. Give him $150 and he'll double your money.” The friend might contact Anderson at the home he shared with his girlfriend, or he might meet Anderson at the local bar or in the back of his souped-up van. Or he might simply text him a credit card number.

Either way, the friend gave Anderson his credit card number and promised to pay him $150 for the money. Then, Anderson, in thirty-second increments at the cash register, punched in the credit. Next, just as rapidly, he'd phone the friend and tell him the deal was done. Finally, the friend would go to the nearest ATM, swipe through his credit card, and—knowing that he had a $300 credit to his account—get $300 in cash.

“So it was basically turning the money right into cash,” says Rooker. “You can see the drug connection here.” Yet a drug connection was never actually proven. What was proven, to quote Rooker, was that a man who “worked fifteen hours a week at Greene's was living the high life. He dressed like a million bucks. He ate at fancy restaurants.” And he wore lots of gold jewelry—and drove a “fully decked-out” conversion van.

The majority of his “customers” looked as though they lived an upper-middle-class life, too, but appearances can be deceiving. Most of them were in the lower-income bracket—Anderson had helped them move up. Sometimes he gave them a $300 pair of shoes to go along with their $300 credit; that way, they could go to another Greene's location, return the shoes, and get an additional $300. One customer was credited $30,000 in one year, says Rooker.

One regular customer was Anderson's girlfriend, who owned the house in which the two lived. And, although she worked as a branch manager for a major bank in Detroit, she was not prosecuted; the Secret Service and the U.S. Attorney, whom Rooker called into the investigation upon his discovery of the perpetrator, decided who was prosecuted.

Anderson was well known by many; he had friends and acquaintances just about everywhere. The fifteen-hour-a-week employee with the big, illegal income was a mover and shaker of sorts. Rooker thinks that was part of Anderson's motive—Anderson hung out with the upper-middle class and was well accepted in their stratum. He wanted to stay in that social group, but the only way he could find to do that was to commit fraud.

Rooker also believes that Anderson simply got “caught up in it” because people came to expect the fraud of him. In fact, they came directly into the store and asked for Anderson: only he could wait on them. Those people were often the ones to whom he gave a pair of shoes as well.

The Secret Service told Rooker that if he would document a minimum of $10,000 in returns via video surveillance, they would go from there. So Rooker had video surveillance equipment installed throughout the shoe department, and at the point-of-sale registers. The first day the equipment was up and running, Anderson was up and running as well; he credited $5,000 that day.

According to Rooker, Anderson simply reached into the inside pocket of his expensive suit jacket, pulled out a list, and started ringing up credits. One day, he gave a single customer a $300 cash refund, a $300 credit refund, and a $300 pair of shoes.

This wreaked havoc on Greene's inventory. Let's say the store's inventory reports showed that there were ten pairs of style 8730 in stock. But then along came Anderson, ringing up a return for style 8730. Suddenly the inventory reports showed eleven pairs of style 8730 in stock, even though there were still only the original ten pairs.

Five thousand dollars of returns in one day caused inventory to be overstated by approximately seventeen pairs of shoes. Seventeen pairs of shoes, five workdays a week, 4.3 weeks per month—and Greene's had a lot of invisible shoes in stock.

Six weeks after the start of in-store surveillance, $30,000 in losses was recorded on videotape—put another way, that's 100 pairs of nonexistent shoes that were falsely reported as in stock.

Most of those losses were documented at the end of each month, because by then, Anderson's customers were in a typical end-of-the-month money crunch. “They came to really depend on this money,” explains Rooker.

The certified fraud examiner next started matching customers to credit card numbers. That was easy to do with the Greene's cards, but it was a slightly harder task for the third-party cards, which were responsible for the majority of the returns.

By working his professional connections, Rooker was able to contact fraud investigators at various banks to find out informally “what was going on” from the banks' perspectives. That's how he learned that some of Anderson's customers were Anderson's friends and relatives.

Ironically, the part-time employee never carried a credit card. He was a cash customer only. His only known asset was his conversion van. The house he shared with his girlfriend was held in her name.

The Secret Service put Anderson under surveillance. Over two weeks, they discovered how he was making his contacts. All day long, friends, relatives, and neighbors streamed in and out of the home he shared with his banker girlfriend. In essence, his fifteen-hour-a-week job demanded more than fifteen hours a week. And often the same people who were observed going into his home received credits that same day.

Anderson had apparently started his “side” job as a bit of a lark and charged only 10 percent of the fictitious refund as his fee. As the scam and his renown grew, he upped his percentage to 25, then 50 percent. Everyone in town, everyone in his shoe department knew he was doing something fishy, reports Rooker, but they were scared to report him. Anderson allegedly carried a gun. And though many liked Anderson, many also feared him.

But that did not deter Rooker and the Secret Service. “The Secret Service was very aggressive,” says Rooker.

They promised to pursue any co-conspirator who had earned at least $5,000 in returns over two years. That led them to Ohio, where they interviewed a middle-aged couple. (Most of Anderson's customers were between the ages of 30 and 50.)

This couple had once lived in the Detroit area. After getting the couple to turn state's evidence (as the Secret Service did with numerous co-conspirators during this investigation), the law enforcement officers learned Anderson's entire scam.

Soon thereafter, four armed U.S. Secret Service agents entered the store, grabbed Anderson, pulled him through the stockroom, and arrested him. When confronted with the crime, Anderson told the agents and Rooker, “Pound sand.” He had $5,000 in cash stuffed into his socks. In his coat pocket, he had a list of fifteen third-party credit card numbers with dollar amounts to credit.

Having those fifteen numbers on his person, says Rooker, was enough to charge the perpetrator. Eventually, though, Rooker learned that $60,000 in refunds had been credited to those fifteen numbers over the previous two years.

Anderson was led through the mall, in handcuffs, by the Secret Service. As he exited, mall store manager after store manager stood at their doors and yelled, “Hey, Joe, what's going on?”

They were worried. They were losing one of their best cash customers.

Local and federal charges for embezzlement and financial transaction card fraud against Anderson and twenty-seven conspirators are pending.

Not pending are new internal controls at Greene's. Rooker implemented them immediately. Over time, another fifty to sixty employees were determined to be pulling off the same scam, at losses of $10,000 to $30,000 to Greene's. The only difference was that these employees were crediting their own charge cards; Anderson only credited other people's charge cards, silently, in thirty-second increments.

False Voids

False voids are similar to refund schemes in that they generate a disbursement from the register. When a sale is voided on a register, a copy of the customer's receipt is usually attached to a void slip, along with the signature or initials of a manager that indicate that the transaction has been approved (see Exhibit 8-5). In order to process a false void, then, the first thing the fraudster needs is the customer's copy of the sales receipt. Typically, when an employee sets about processing a fictitious void, he simply withholds the customer's receipt at the time of the sale. If the customer requests the receipt, the clerk can produce it, but in many cases customers simply do not notice that they didn't receive a receipt.

With the customer copy of the receipt in hand, the culprit rings a voided sale. Whatever money the customer paid for the item is removed from the register as though it were being returned to a customer. The copy of the customer's receipt is attached to the void slip to verify the authenticity of the transaction.

Before the voided sale will be perceived as valid, a manager generally must approve it. In many of the cases in the ACFE studies, the manager in question simply neglected to verify the authenticity of the voided sale. Such managers signed essentially anything presented to them, thus leaving themselves vulnerable to a voided sales scheme. An example of this kind of managerial nonchalance occurred in Case 1753. In this case a retail clerk kept customer receipts and “voided” their sales after the customers left the store; the store manager signed the void slips on these transactions without taking any action to verify their authenticity. A similar breakdown in review was detected in Case 1787, where an employee processed fraudulent voids, kept customer receipts, and presented them to her supervisors for review at the end of her shift, long after the alleged transactions had taken place. Her supervisors approved the voided sales, and the accounts receivable department failed to notice the excessive number of voided sales processed by this employee.

It was not a coincidence that the perpetrators of these crimes presented their void slips to a manager who happened to be lackadaisical about authorizing them. Generally, such managers are essential to the employee's schemes.

Because not all managers are willing to provide rubber-stamp approval of voided sales, some employees take affirmative steps to get their voided sales “approved.” This usually amounts to forgery, as in Case 1753 (previously noted) whereby the fraudster eventually began forging his supervisor's signature as the employee's false voids became more and more frequent.

Finally, it is possible that a manager will conspire with a register employee and approve false voids in return for a share of the proceeds. Although ACFE researchers did not encounter any cases like this in their studies, they did come across several examples of managers helping employees to falsify time cards or expense reimbursement requests. There is no reason why the same kind of scheme would not also work with false voids.

CONCEALING REGISTER DISBURSEMENTS

As we discussed above, when a false refund or void is entered into the register, two things happen. First, the employee who is committing the fraud removes cash from the register; second, the item allegedly being returned is debited back into inventory. This leads to shrinkage: a situation in which there is less inventory actually on hand than the inventory records reflect. A certain amount of shrinkage is expected in any retail industry, but too much of it raises concerns of fraud.

Remember: inventory is accounted for by a two-step process. The first part of the process is the perpetual inventory, which is essentially a running tabulation of how much inventory should be on hand. When a sale of merchandise is made, the perpetual inventory is credited to remove this merchandise from the records; the amount of merchandise that should be on hand is reduced. Periodically, someone from the company takes a physical count of the inventory, going through the stockroom or warehouse and counting the amount of inventory that is actually on hand. The two figures are then compared to see if there is a discrepancy between the perpetual inventory (what should be on hand) and the physical inventory (what is on hand). When a fraudulent refund or void has been recorded, the amount of inventory that is actually on hand will be less than the amount that should be on hand.

Typically, fraudsters do not make any effort to conceal the shrinkage that results from their schemes. In many register disbursement cases, the amount of shrinkage is not large enough to raise a red flag, but in large-scale cases the amount of shrinkage caused by a fraudster can be quite significant. For example, in the previous case study, Joe Anderson, a part-time employee, rang up $150,000 in documented fictitious returns in a scheme that had a significant effect on the victim company's inventory. An excessive number of reversing transactions, combined with increased levels of shrinkage, would generally be considered a strong indicator of register disbursement fraud. For a discussion of how fraudsters attempt to conceal shrinkage, please see Chapter 9.

Aside from shrinkage, a register disbursement scheme leaves the victim organization's books in balance. The whole purpose of recording a fraudulent refund or void, after all, is to account for the stolen funds and to justify their removal from the cash drawer. Therefore, fraudsters often take no further steps to conceal a register disbursement scheme. However, a register disbursement scheme can still be detected if someone notices abnormal levels of refunds or voids. There are two methods that fraudsters often use to avoid this form of detection.

Small Disbursements

One common concealment technique is to keep the sizes of the disbursements low. Many companies set limits below which management review of a refund is not required. When this is the case, fraudsters simply process copious numbers of refunds that are small enough that they need not be reviewed. In Case 791, for example, an employee created over 1,000 false refunds, all under the review limit of $15. He was eventually caught because he began processing refunds before store hours; another employee noticed that refunds were appearing on the system before the store opened. Nevertheless, before his scheme was detected, the employee made off with over $11,000 of his employer's money.

Destroying Records

One final means of concealing a register scheme, as with many kinds of fraud, is to destroy all records of the transaction. Most concealment methods are concerned with keeping management from realizing that fraud has occurred. When an employee resorts to destroying records, however, he typically has conceded that management will discover his theft. The purpose of destroying records is usually to prevent management from determining who the thief is. In Case 2728, for example, a woman was creating false inventory vouchers that were reflected on the register tape. She then discarded all refund vouchers, both legitimate and fraudulent. Because documentation was missing on all transactions, it was extremely difficult to distinguish the good from the bad. Thus, it was hard to determine who was stealing.

PREVENTING AND DETECTING REGISTER DISBURSEMENT SCHEMES

The best way for organizations to prevent fraudulent register disbursements is to always maintain appropriate separation of duties. Management approval should be required for all refunds and voided sales in order to prevent a rogue employee from generating fraudulent disbursements at his cash register. Access to the control key or management code that authorizes reversing transactions should be closely guarded, and cashiers should not be allowed to reverse their own sales.

In addition to management review, voided transactions should be properly documented. Require a copy of the customer's receipt from the initial purchase, which should be attached to a copy of a void slip or other documentation of the transaction. This documentation should be retained on file.

Every cashier or sales clerk should be required to maintain a distinct login code for work at the register, allowing voids and refunds to be traced back to the employee who processed them. Periodically, organizations should generate reports of all reversing transactions at the register, looking for employees who tend to process an inordinate number of these transactions. Recurring transaction amounts, particularly in round numbers such as $50, $100, and so on, are also common indicators of register disbursement fraud.

If the organization requires management approval only for voids and refunds above a certain amount, look for large numbers of transactions just below this amount. For instance, if the minimum review amount is $20, fraudsters might process multiple refunds for $19 in order to avoid review.

One way to help deter register disbursements is to place signs or institute store policies encouraging customers to ask for and examine their receipts. For example, offer a discount to any customer who does not receive a receipt. This will prevent employees from retaining customer receipts to use as support for false voids or refunds.

Random customer service calls can also be made to customers who have returned merchandise or voided sales as a way of verifying that these transactions actually took place. This type of verification is effective only if the persons who make the customer service calls are independent of the cash receipts function.

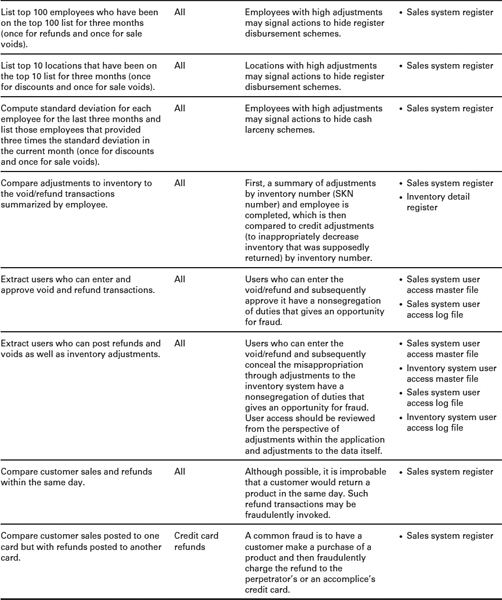

PROACTIVE COMPUTER AUDIT TESTS FOR DETECTING REGISTER DISBURSEMENT SCHEMES1

SUMMARY

Two basic types of fraudulent disbursement schemes take place at the cash register: false refunds and false voids. In a false refund scheme, an employee fraudulently records a return of merchandise and a corresponding disbursement of cash from his register. The false transaction accounts for the theft of cash and keeps the register in balance, because the amount of money stolen is equal to the amount of the fraudulent disbursement. Typically, false refund schemes involve wholly fictitious transactions, though in some cases an actual refund will be overstated and the perpetrator will steal the excess amount. Although most false refund schemes involve the fraudulent disbursement of cash from the register, in some cases perpetrators run a bogus refund to a credit card account, whether their own or an accomplice's.

False voids are similar to false refunds. They occur when a perpetrator uses a confiscated customer sales slip to void a sale. The scheme is consummated when the employee takes cash from the register in an amount equaling the amount on the sales slip.

In many cases, there is no effort made to conceal register disbursements, because the fraudulent transaction is designed to account for the stolen funds and the cash register remains in balance after the theft. But it may still be necessary to conceal the fact that an inordinate number of reversing transactions have been processed. To accomplish this, fraudsters typically either process fraudulent voids or refunds in small amounts that fall below review limits or destroy records of the fraudulent transactions.

ESSENTIAL TERMS

False refund scheme One of two main categories of register disbursements, in which a fraudulent refund is processed at the cash register to account for stolen cash.

Fictitious refund scheme A false refund scheme in which an employee processes a fake refund transaction as if a customer were actually returning merchandise and pockets the cash instead.

Overstated refund scheme A false refund scheme in which an employee overstates the amount of a legitimate customer refund, then gives the customer the actual amount of the refund and steals the excess.

False void scheme One of two main categories of register disbursements. A scheme in which an employee accounts for stolen cash by voiding a previously recorded sale.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

8-1 (Learning objective 8-1) What is a register disbursement scheme?

8-2 (Learning objective 8-2) How do register disbursement schemes differ from skimming and cash larceny, both of which frequently involve thefts of cash from cash registers?

8-3 (Learning objective 8-3) What are the two main categories of register disbursement schemes?

8-4 (Learning objective 8-4) What is the difference between a fictitious refund scheme and an overstated refund scheme?

8-5 (Learning objective 8-5) How are fraudulent void schemes used to generate a disbursement from a cash register?

8-6 (Learning objective 8-6) How do register disbursement schemes cause shrinkage?

8-7 (Learning objective 8-7) How can the processing of low-dollar refunds help a fraudster conceal a register disbursement scheme?

8-8 (Learning objective 8-8) Why is it important for all cashiers to maintain distinct login codes for work at the cash register?

DISCUSSION ISSUES

8-1 (Learning objective 8-4) In the case study involving Bob Walker at the beginning of this chapter, what type of register disbursement schemes did he commit? Discuss the role his recent demotion played in the scheme.

8-2 (Learning objective 8-2) In the 2011 Global Fraud Survey, register disbursements were reported far less frequently than any other fraudulent disbursement scheme. Discuss some reasons why this result might not reflect the true frequency of register disbursements.

8-3 (Learning objectives 8-8 and 8-9) What are some tests that can help detect fictitious refund schemes that involve the overstatement of inventories?

8-4 (Learning objective 8-8-4) In the “silent crime” case study mentioned in the chapter, how did Joe Anderson involve other individuals in his credit card refund scheme?

8-5 (Learning objectives 8-8 and 8-9) Explain how each of the following three conditions could be a red flag for a register disbursement scheme.

- Able, a cash register teller, is authorized to approve sales refunds; he is also authorized to make inventory adjustments.

- Baker, a cashier, processed fifteen refunds in the last week. No other cashier processed more than five during that same period. Each of the transactions was for between $13.50 and $14.99.

- Over 70 percent of the refunds processed by Chase, a cash register clerk, were run on the same date as the original sale.