LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

| 9-1 | List the five categories of tangible noncash misappropriations discussed in this chapter |

| 9-2 | Discuss the data on noncash misappropriations from the 2011 Global Fraud Survey |

| 9-3 | Explain how misuse of noncash assets can negatively affect organizations |

| 9-4 | Understand how and why unconcealed larceny of noncash assets occurs |

| 9-5 | Be familiar with internal controls and tests that can be used to prevent and detect noncash larceny |

| 9-6 | Understand how weaknesses in internal asset requisition and transfer procedures can lead to the misappropriation of noncash assets |

| 9-7 | Explain how purchasing and receiving schemes are used to misappropriate noncash assets |

| 9-8 | Understand how the theft of noncash assets through the use of fraudulent shipments is accomplished |

| 9-9 | Define shrinkage |

| 9-10 | Describe how fraudsters conceal the theft of noncash assets on the victim organization's books |

| 9-11 | Understand how employees can misappropriate intangible assets, as well as how companies can protect themselves from such schemes |

| 9-12 | Be familiar with proactive audit tests that can be used to detect misappropriations of noncash assets |

CASE STUDY: CHIPPING AWAY AT HIGH-TECH THEFT1

Nineteen-year-old Larry Gunter didn't know much about computers, but he worked as a shipping clerk in a computer manufacturer's warehouse. Like many other companies in Silicon Valley, this company produced thousands of miniature electronic circuits—microprocessor chips—the building block of personal computers.

Gunter didn't work in the plant's “clean room” building, where the chips were manufactured. The company moved the chips, along with other computer components, next door to the warehouse for processing and inventory.

On the open market, one of these computer chips, which is comprised of hundreds of millions of transistors packed into a space no bigger than a fingernail, is worth about $40. Over 1,000 chips were packaged in plastic storage tubes inside a company-marked cardboard box.

Gunter knew they were worth something, but he didn't know how much. One day, he took a chip from a barrel in the warehouse and gave it to his girlfriend's father, Grant Thurman, whom he knew operated some type of computer salvage business. He told Thurman that the company had discarded the chip as “scrap.”

“I asked him if he knew anyone who would buy scrap chips,” Gunter said, and Thurman said he did. “So after about another week or two I stole three boxes of computer chips and brought them to Grant to sell them to his computer guy. Around a week later I got paid by Grant Thurman in the amount of $5,000 in a personal check.”

Gunter knew the chips were not scrap, since the boxes, each about the size of a shoebox, bore the marking “SIMMS,” signifying that the chips were sound. In fact, the manufacturer maintained a standard procedure for scrap chips, taking them to another warehouse on the company's grounds and sealing the components for shipment to another plant for destruction.

Gunter concealed the boxes from the security guards by placing them on the bottom of his work cart, with empty boxes on top. He pushed the cart out of the warehouse as if he were just taking empty boxes to the trash. Once in the parking lot, where there were no security guards, he loaded the three boxes of chips into his truck.

Shortly after the theft, an inventory manager filling an order noticed that many company chips were missing and immediately went to his supervisor, the warehouse manager. The manager verified that they were missing about ten cartons of chips, worth over $30,000. They contacted the company's director of operations, who accelerated the product inventory process at the plant. Instead of taking product inventory once a month, he began taking it once a week.

Gunter still found it easy to steal, he said, because the security guards didn't pay much attention and because it was easy to evade the stationary surveillance cameras in the warehouse. About two weeks after his first theft, he stole four boxes of new chips, for which Thurman paid him $10,000. Excited about his new conquest, Gunter told his young friend and coworker, Larry Spelber, about the easy profit to be made. The two could split $50,000 from a theft of six boxes of chips, he told Spelber—enough to quit work and finance their schooling.

By this time, however, the company had detected the second loss and contacted private investigator and fraud examiner Lee Roberts. Roberts, head of Roberts Protection & Investigations, had worked with the company's attorney before.

“They knew exactly how much of their product they were missing,” Roberts said, “because no product was supposed to leave the building unless they had the paper for loading it on the truck to fill a specific order. However, there was a flaw in the system. The company's operation was separated in two buildings, about 300 feet apart. They would receive an extremely valuable product, and it would go from one building to the other simply by being pushed by employees with carts through this 300-foot parking lot. Consequently, they would end up with an overstock of product that needed to leave the warehouse and be returned to Building One. Of course, that generated no internal paperwork; someone would simply say ‘I'm taking this product to Building Two’ or vice versa, and that was such a common occurrence that the security guards started to think nothing about it.”

“My immediate concern was,” Roberts said, “if we've got something leaving the building in the ordered process, then we must have supervisors involved, drivers involved, and the like. It would be a fairly massive operation, and maybe that was their concern.”

Roberts suspected the thefts occurred between these interbuilding transfers. Since the employees who did these transfers were the thirty or so warehouse floor workers, he had many potential suspects.

To catch the thieves, however, a new video surveillance system would need to be set up at the warehouse. “We looked at their video surveillance system and found their cameras were improperly positioned, and they were not saving their tapes in the library long enough to go back and look at them.” Roberts's firm, which partly specializes in alarms and security protection, set up an additional sixteen hidden video cameras inside the warehouse, as well as additional cameras in the parking lots.

“We agreed to pretend that nothing had happened,” Roberts said of the thefts, “which would give the suspects a false sense of security, and the company agreed to restock the computer chips.”

The warehouse manager and his assistant began to surreptitiously track interbuilding transfers on a daily basis. With access to the paperwork and new video, “we were able to freeze-frame images” in order to look at all sides of an employee's cart. This time, the warehouse manager knew exactly how many boxes an employee was supposed to be taking to the other building.

Unbeknownst to Gunter and Spelber, the video cameras recorded them talking in the aisleways and other areas of the warehouse. Coupled with the daily inventory check, the record showed that the two employees frequently had more than the number of boxes they were supposed to be moving.

About 3:30 one afternoon, Gunter and Spelber removed six boxes from the shelves, placed them on a cart with empty boxes on top, and moved the cart outside. In the parking lot, Spelber loaded the boxes into his truck and returned to work. After work, they drove their own vehicles down the street and transferred the boxes to Gunter's car.

At home, Gunter removed the company labels from the chips and drove to Thurman's house. Thurman promised to pay him $50,000 for this stock.

Gunter and Spelber never saw that money. The next day, company security confronted them with the evidence. They quickly admitted their guilt and identified Thurman as the receiver of the stolen equipment. When police interviewed Thurman at his home, he denied knowing that the computer chips were stolen, but he admitted to reselling the chips to an acquaintance named Marty for $180,000, paid for with cashier's checks.

Interviews with Marty, along with check receipts, revealed that the amount was actually much greater—Marty had paid approximately $697,000 to Thurman for the chips (a profit of about 50 cents on the dollar, as compared to the 10 cents on the dollar Gunter received). Although investigators could not uncover any stolen equipment, they believed that Marty had sold the goods to the aerospace industry and possibly to federal agencies.

The next day, police arrested Thurman after he attempted to make a large withdrawal from his credit union. Thurman and Gunter both served over a year in the state pen for grand theft and embezzlement; Spelber got nine months in a work furlough program. The police were never able to tag anything on Marty, who made the most money in the open market for the chips. Since none of the product could be found in his store, and since investigators could not prove he knew the property was stolen, they could not criminally prosecute him.

Roberts said the case was unique in that, at the time, it represented the largest internal theft in the history of this California county. The company, though unable to recover most of the stolen property, learned a valuable lesson from the fraud. Afterward, managers conducted tighter controls on transfers of property between buildings, produced more frequent inventory audits, and established enhanced physical security, which included a new chain-link fence between the two buildings.

“I think this fraud was difficult to detect because the audit controls that they set up, and the manner in which they had set them up, were improper,” Roberts said. “That's a common thing that we see as fraud examiners or investigators. Often people spend a great deal of money to set up audit controls—they set up physical security; they install alarms—and we often say to them: Simply buying that piece of equipment or putting those procedures into place is not enough. You need a trained, experienced professional to tell you how to do it and how to use them. If you don't do it the right way, it's worthless.”

OVERVIEW

Up to this point in the book, our discussion of asset misappropriations has focused on cash schemes. While the vast majority of asset misappropriation schemes involve cash, it should be remembered that other assets can be stolen as well (see Exhibit 9-1). Although schemes involving the misappropriation of noncash assets are not as common as cash schemes, they are nevertheless potentially disastrous. As Larry Gunter's scheme illustrates, thefts of inventory can run into the millions of dollars. In this chapter we will discuss the ways in which employees misappropriate noncash assets, such as inventory, supplies, equipment, and information.

Noncash Misappropriation Data from the ACFE 2011 Global Fraud Survey

Frequency and Cost Noncash schemes were not nearly as common as cash schemes in the ACFE survey, accounting for only 20 percent of asset misappropriations (see Exhibit 9-2). Additionally, as indicated in Exhibit 9-3, noncash schemes had a lower median cost than frauds that targeted cash.

Types of Noncash Assets Stolen By far, physical assets, including inventory and equipment, were the most commonly misappropriated noncash asset in the ACFE study. Fraudsters embezzled physical assets in 75 percent of the cases involving noncash misappropriations (see Exhibit 9-4).

Although securities were the least likely asset to be misappropriated (20 cases), the median loss in cases involving securities theft was significantly higher than in any other category, at $330,000 (see Exhibit 9-5).

EXHIBIT 9-2 2011 Global Fraud Survey: Comparison of Frequency of Asset Misappropriations*

EXHIBIT 9-3 2011 Global Fraud Survey: Comparison of Median Loss of Asset Misappropriations

EXHIBIT 9-4 2011 Global Fraud Survey: Noncash Cases by Type of Asset Misappropriated

EXHIBIT 9-5 2011 Global Fraud Survey: Median Loss in Noncash Cases by Type of Asset Misappropriated

NONCASH MISAPPROPRIATION SCHEMES

Noncash tangible assets, such as inventory and equipment, are misappropriated by employees in a number of ways. These schemes can range from taking a box of pens home from work to the theft of millions of dollars' worth of company property. In general, misappropriations of noncash tangible assets fall into one of the following categories:

- Misuse

- Unconcealed larceny

- Asset requisitions and transfers

- Purchasing and receiving schemes

- Fraudulent shipments

Misuse of Noncash Assets

There are basically two ways a person can misappropriate a company asset. The asset can be misused (or “borrowed”), or it can be stolen. Simple misuse is obviously the less egregious of the two. Assets that are misused, but not stolen, typically include company vehicles, company supplies, computers, and other office equipment. In Case 1421, for example, an employee made personal use of a company vehicle while on an out-of-town assignment. The employee provided false information, both written and verbal, regarding the nature of his use of the vehicle. The vehicle was returned unharmed and the cost to the perpetrator's company was only a few hundred dollars, but such unauthorized use of a company asset does amount to fraud when a false statement accompanies the use.

Computers, supplies, and other office equipment are also used by some employees to do personal work on company time. For instance, an employee might use his computer at work to write letters, print invoices, or do other work connected with a business that he runs on the side. In some instances, these side businesses are of the same nature as the employer's business, in which case the employee is using his employer's equipment to compete with the employer. An example of how employees misuse company assets to compete with their employers was provided by Case 1406, in which a group of employees not only stole company supplies, but also used the stolen supplies, in conjunction with their employer's equipment, to manufacture their own product. The fraudsters then removed the completed product from their work location and sold it in competition with their employer. In a similar scheme, the perpetrator of Case 2579 used his employer's machinery to run his own snow removal and excavation business for approximately nine months. He generally did his own work on weekends and after hours, falsifying the logs that recorded mileage and usage on the equipment. The employee had formerly owned all the equipment himself, but had sold it in order to avoid bankruptcy. As a term of the sale, he had agreed to go to work for the new owner operating the equipment, but in truth, he never stopped running his old business.

The preceding cases offer a good illustration of how a single scheme can encompass more than one type of fraud. Though the perpetrators in these schemes were misusing company materials and equipment—a case of asset misappropriation—they were also competing with their employers for business—a conflict of interest. The categories ACFE researchers have developed for classifying fraud are helpful in that they allow examiners to track certain types of schemes, noting common elements, victims, methods, and so on; but those involved in fraud prevention should remember that every crime will not fall neatly into one category. Frauds often expand as opportunity and need allow; a scheme that begins small may grow into a massive crime that can cripple a business.

The Costs of Inventory Misuse The costs of noncash asset misuse are difficult to quantify. To many individuals this type of fraud is viewed not as a crime, but rather as “borrowing.” In truth, the cost to a company from this kind of scheme may often be immaterial. When a perpetrator borrows a stapler for the night or takes home some tools to perform a household repair, the cost to his company is negligible, as long as the assets are returned unharmed.

But misuse schemes can also be very costly. Take, for example, situations such as those discussed above in which an employee uses company equipment to operate a side business during work hours. Since the employee is not performing his work-related duties, the employer suffers a loss in productivity. If the low productivity continues, the employer might have to hire additional employees to compensate, diverting more capital to wages. If the employee's business is similar to the employer's, lost business could be an additional cost; had the employee not contracted work for his own company, the business would presumably have gone to his employer. Unauthorized use of equipment can also mean additional wear and tear, causing the equipment to break down sooner than it would have under normal business conditions. Additionally, when an employee “borrows” company property, there is no guarantee that he will bring it back. This is precisely how some theft schemes begin. Despite some opinions to the contrary, asset misuse is not always a harmless crime.

Unconcealed Larceny Schemes

Though the misuse of company property might be a problem, the theft of company property is obviously of greater concern. As we have seen, losses resulting from larceny of company assets can run into the millions of dollars. The means employed to steal noncash assets range from simple larceny—just walking off with company property—to more complicated schemes involving the falsification of company documents and ledgers.

The textbook definition of larceny is too broad for our purposes, as it would encompass every kind of theft. In order to gain a more specific understanding of the methods used to steal noncash assets, we have narrowed the definition of larceny. For our purposes, larceny is the most basic type of theft, exhibited in schemes in which an employee simply takes property from the company premises without attempting to conceal it in the books and records (see Exhibit 9-6). In other fraud schemes, employees might create false documentation to justify the shipment of merchandise or tamper with inventory records to conceal missing assets, but larceny is simpler. The culprit in these crimes simply takes company assets, without trying to account for their absence. In the case study at the beginning of this chapter, for instance, Larry Gunter merely walked out of his warehouse with several hundred thousand dollars' worth of computer chips.

EXHIBIT 9-6 Noncash Larceny

Most noncash larceny schemes are not very complicated. They are typically committed by employees (such as warehouse personnel, inventory clerks, and shipping clerks) who have access to inventory and other assets. A typical example of this type of scheme was committed by the perpetrator of Case 968, a warehouse clerk who simply removed inventory from outgoing shipments and left it in plain sight on the warehouse floor as he went about his duties. If someone noticed that a shipment was short, the fact that the merchandise was sitting out in the open made it appear that the omission had been an oversight rather than an intentional removal. In most cases, however, no one noticed that shipments were short, leaving the excess inventory available for the perpetrator to take. If customers complained about receiving short shipments, the company sent the missing items without performing any follow-up to see where the missing inventory had gone. The culprit was eventually caught when someone noticed that he was involved in the preparation of an inordinate number of short shipments.

When we speak of inventory theft, we tend to conjure up images of late-night rendezvous at the warehouse or merchandise stuffed hastily under clothing as a nervous employee beats a path to his car. Although sometimes this is how employees go about stealing inventory and other assets, in many instances fraudsters do not have to go to these extremes. In several of the cases in our studies, employees took items openly during business hours, in plain view of their coworkers. How does this happen? The truth is that people tend to assume that their friends and acquaintances are acting honestly. When they see a trusted coworker taking something out of the office, people are likely to assume that the culprit has a legitimate reason for removing the asset. In most cases, people just don't assume that fraud is going on around them. Such was the situation in Case 728, in which a university faculty member was leaving his offices to take a position at a new school. This person was permitted to take a small number of items to his new job, but certainly exceeded the intentions of the school when he loaded two trucks full of university lab equipment and computers worth several hundred thousand dollars. The perpetrator simply packed up these stolen assets along with his personal items and drove away.

Though it is true that employees sometimes misappropriate assets in front of coworkers who do not suspect fraud, it is also true that employees may be fully aware that one of their coworkers is stealing, yet refrain from reporting the crime. There are several reasons why employees might ignore illegal conduct, among them a sense of duty to friends, a “management versus labor” mentality, intimidation by the thief, or poor channels of communication—or the coworkers may be assisting in the theft. When high-ranking personnel are stealing from their companies, employees often overlook the crime for fear that they will lose their jobs if they report it. For example, a school superintendent in Case 2462 was not only pilfering school accounts, but also stealing school assets. A search of his residence revealed a cellar filled with school property. A number of school employees knew or suspected the superintendent was involved in illegal dealings, but he was very powerful, and people were afraid to report him for fear of retaliation. As a result, he was able to steal from the school for several years. Similarly, in Case 144, a city manager ordered subordinates to install air conditioners—known to be city property—in his home and in the homes of several influential citizens. Although there was no question that this violated the city's code of ethics, no one reported the manager because of a lack of a proper whistle-blowing procedure in the department.

Ironically, employees who steal company property are often highly trusted within their organizations. This trust can provide employees with access to restricted areas, safes, supply rooms, or even keys to the business. Such access, in turn, makes it easy for employees to misappropriate company assets. Case 716 provides an example of how an employee abused his position of trust to misappropriate noncash assets. In this case, a long-term employee of a contractor was given keys to the company parts room. It was his job to deliver parts to job sites. This individual used his access to steal high-value items that he then sold to another contractor. The scheme itself was uncomplicated, but because the employee had a long history of service to the company, and because he was highly trusted, inventory counts were allowed to lapse and his performance went largely unsupervised. As a result, the scheme continued for over two years and cost the company over $200,000.

Employees who have keys to company buildings are able to misappropriate assets during nonbusiness hours, when they can avoid the prying eyes of their fellow employees as well as management and security personnel. The ACFE studies revealed several schemes in which employees entered their places of business to steal assets during weekends, as well as before or after normal working hours. Case 1766 provided an example of this after-hours activity. In this scheme two employees in management positions at a manufacturing plant would set finished items aside at the end of the day, then return the next day an hour before the morning shift and remove the merchandise before other employees arrived. These perpetrators had keys to the plant's security gate, which allowed them to enter the plant before normal hours. Over the course of several years, these two fraudsters removed and sold approximately $300,000 worth of inventory from their company.

It can be unwise for a fraudster to physically carry inventory and other assets off the premises of his company. This practice carries with it the inherent risk and potential embarrassment of being caught red-handed with stolen goods on his person. Some fraudsters avoid this problem by mailing company assets to a location where they can pick them up without having to worry about security, management, or other potential observers. In Case 1465, for instance, a spare-parts custodian took several thousand dollars' worth of computer chips and mailed them to a company that had no business dealings with the custodian's employer. He then reclaimed the merchandise as his own. By taking the step of mailing the stolen inventory, the fraudster allowed the postal service to unwittingly do his dirty work for him.

The Fake Sale Asset misappropriations are not always undertaken solely by employees of the victim organization. In many cases, corrupt employees use outside accomplices to help steal an organization's property. The fake sale is one method that depends on an accomplice for its success. Like most larceny schemes, the fake sale is not complicated. As reflected in Case 1963, a fake sale occurs when the accomplice of the employee-fraudster “buys” merchandise but the employee does not ring up the sale; the accomplice takes the merchandise without making any payment. To a casual observer, it will appear that the transaction is a normal sale. The employee bags the merchandise and may act as though a transaction is being entered on the register, but in fact, the “sale” is not recorded. The accomplice may even pass a nominal amount of money to the employee to complete the illusion. In Case 1963 the perpetrator went along with these fake sales in exchange for gifts from her accomplice, though in other cases the two might split the stolen merchandise.

Accomplices are also sometimes used to return the inventory that an employee has stolen. This is an easy way for the employee to convert the inventory into cash when he has no need for the merchandise itself and has no means of reselling it on his own.

Preventing and Detecting Larceny of Noncash Assets In order to prevent larceny of noncash assets, the duties of requisitioning, purchasing, and receiving these assets should be segregated. To provide additional checks and balances, the payables function should be segregated from all purchasing and receiving duties. In addition, physical controls are a key to preventing theft of noncash assets. All merchandise should be physically guarded and locked, with access restricted to authorized personnel only. Access logs can be used to track those who enter restricted areas, or each authorized individual could be given a personalized entry code. In either case, a log will be created that shows who had access to restricted assets and at what times. Not only will this help identify the perpetrator in the event that a theft occurs, but—more important—it will help deter employees from attempting to steal company merchandise.

Another potentially effective deterrence method is the installation of security cameras in warehouses or on sales floors. If security cameras are to be used, their presence should be made known to employees to deter misconduct. Security guards can also be used for the same purpose.

In order to help detect inventory thefts in a timely manner, organizations should conduct physical inventory counts on a periodic basis, and someone independent of the purchasing and warehousing functions should conduct these counts. Physical counts should be comprehensive. Also, boxes should be inspected to make sure they actually contain inventory. Physical inventory counts should be subject to recounts or spot checks by independent personnel. Also, shipping and receiving activities should be suspended during physical counts to ensure a proper cutoff. Significant discrepancies between physical counts and perpetual inventory (shrinkage) should be investigated before adjustments are made to inventory records.

One common way to commit inventory theft is to remove items from outgoing shipments of merchandise. It is therefore important for organizations to have in place a mechanism for receiving customer complaints regarding, among other things, “short” shipments. An employee who is independent of the purchasing and warehousing functions should be assigned to follow up on complaints. If a large number of complaints are received, the dates of shipment can be compared to employee work schedules to help identify suspects.

Asset Requisitions and Transfers

Asset requisitions or other documentation that enable noncash assets to be moved from one location in a company to another can be used to facilitate the misappropriation of those assets. Fraudsters use these internal documents to gain access to merchandise that they otherwise might not be able to handle without raising suspicion. Transfer documents do not account for missing merchandise the way false sales do, but they allow a fraudster to move assets from one location to another. In the process of this movement, the fraudster takes the merchandise for himself (see Exhibit 9-6).

The most basic scheme occurs when an employee requisitions materials to complete a work-related project, then steals the materials instead. In some cases the fraudster simply overstates the amount of supplies or equipment it will take to complete his work, and pilfers the excess. In more extreme cases, the fraudster might completely fabricate a project that necessitates the use of certain assets he intends to steal. In Case 2744, for instance, an employee of a telecommunications company used false project documents to request approximately $100,000 worth of computer chips, allegedly to upgrade company computers. Knowing that this type of requisition required verbal authorization from another source, the employee set up an elaborate phone scheme to get the “project” approved. The fraudster used his knowledge of the company's phone system to forward calls from four different lines to his own desk. When the confirmation call was made, it was the perpetrator who answered the phone and authorized the project.

Dishonest employees sometimes falsify property transfer forms so that they can remove inventory or other assets from a warehouse or stockroom. Once the merchandise is in their possession, the fraudsters simply take it home with them. In Case 653, for example, a manager requested that merchandise from the company warehouse be displayed on a showroom floor. But the pieces he requested never made it to the showroom, because he loaded them into a pickup truck and took them home. In some instances he actually took the items in broad daylight and with the help of another employee. The obvious problem with this type of scheme is that the person who orders the merchandise will usually be the primary suspect when it turns up missing. In many cases the fraudster simply relies on poor communication between different departments in his company and hopes no one will piece the crime together. The individual in this case, however, thought he was immune to detection, because the merchandise was requested via computer, using a management-level security code. Because the code was not specific to any one manager, he thought there would be no way of knowing which manager had ordered the merchandise. Unfortunately for the thief, the company was able to record the computer terminal from which the request originated. The manager had used his own computer to make the request, which led to his undoing.

When inventory is stored in multiple locations, the transfer of assets from one building to another can create opportunities for employees to pilfer. Larry Gunter, in the case study at the beginning of this chapter, stole over $1 million worth of computer chips by adding extra merchandise to his cart as he transferred materials between two company buildings or as he took out the trash. He simply took a detour and loaded the stolen chips in his truck before continuing on his route. As is the case in many businesses, Larry Gunter's company required no internal paperwork when product was moved between its two buildings, so it was very difficult to track the movement of assets. Consequently, it was easy for Gunter to steal from the company.

Purchasing and Receiving Schemes

The purchasing and receiving functions of a company can also be manipulated by dishonest employees to facilitate the theft of noncash assets (see Exhibit 9-6). It might at first seem that any purchasing scheme should fall under the heading of false billings, but there is a distinction between purchasing schemes that are classified as false billings and those that are classified as noncash misappropriations. If an employee causes his company to purchase merchandise that the company does not need, this is a false billing scheme: the harm to the company comes in paying for assets for which it has no use. For instance, in Case 1693 a carpenter was allowed control over the ordering of materials for a small construction project. No one bothered to measure the amount of materials ordered against the size of the carpenter's project, so the carpenter was able to order excess, unneeded lumber, which was then delivered to his home, to build a fence for himself. The essence of the fraud in this case was the purchase of unneeded materials.

On the other hand, if the assets were intentionally purchased by the company but simply misappropriated by the fraudster, this is classified as a noncash scheme. In the preceding example, assume that the victim company wanted to keep a certain amount of lumber on hand for odd jobs. If the carpenter took this lumber home, the crime is a theft of lumber. The difference is that, in the second example, the company is deprived not only of the cash it paid for the lumber, but also of the lumber itself. It will now have to purchase more lumber to replace what it is missing. In the first example, the company's only loss was the cash it paid in the fraudulent purchase of the materials it did not need.

Falsifying Incoming Shipments One of the most common ways for employees to abuse the purchasing and receiving functions is for a person charged with receiving goods on behalf of the victim company—such as a warehouse supervisor or receiving clerk—to falsify the records of incoming shipments. In Case 684, for instance, two employees conspired to misappropriate incoming merchandise by marking shipments as short. If 1,000 units of a particular item were received, for example, the fraudsters would indicate that only 900 were received. They were then able to steal the 100 units that were unaccounted for.

The obvious problem with this kind of scheme is that if the receiving report does not match the vendor's invoice, there will be a problem with payment. In the above example, if the vendor bills for 1,000 units but the accounts payable voucher shows receipt of only 900 units of merchandise, then someone will have to explain where the extra 100 units went. Obviously, the vendor will indicate that a full shipment was made, so the victim company's attention will likely turn to whoever signed the receiving reports.

In this case, the fraudsters attempted to avoid this problem by altering only one copy of the receiving report. The copy that was sent to accounts payable indicated receipt of a full shipment so that the vendor would be paid without any questions. The copy used for inventory records indicated a short shipment so that the assets on hand would equal the assets in the perpetual inventory.

Instead of marking shipments short, the fraudster might reject portions of a shipment as not being up to quality specifications. The perpetrator then keeps the “substandard” merchandise rather than sending it back to the supplier. The result is the same as if the shipment had been marked short.

False Shipments of Inventory and Other Assets

To conceal thefts of inventory, fraudsters sometimes create false shipping documents and false sales documents to make it appear that missing inventory was not actually stolen but was instead sold (see Exhibit 9-7). The document that tells the shipping department to release inventory for delivery is usually the packing slip. By creating a false packing slip, a corrupt employee can cause inventory to be fraudulently delivered to himself or to an accomplice. The “sales” reflected in the packing slips are typically made to a fictitious person, a fictitious company, or an accomplice of the perpetrator. In Case 1598, for instance, an inventory control employee used his position to create fraudulent paperwork that authorized the shipment of over $30,000 worth of inventory to his accomplices. The fraudsters were then able to sell the inventory for their own profit.

One benefit to using false shipping documents to misappropriate inventory or other assets is that someone other than the fraudster can remove the product from the warehouse or storeroom. The perpetrator of the scheme does not have to risk being caught stealing company inventory. Instead, the victim company unknowingly delivers the targeted assets to him.

EXHIBIT 9-7 False Shipments of Inventory and Other Assets

Packing slips allow inventory to be shipped from the victim company to the perpetrator, but they alone do not conceal the fact that inventory has been misappropriated. In order to hide the theft, fraudsters may also create a false sale so that it appears that the missing inventory was shipped to a customer. In this way, the inventory is accounted for. Depending on how the victim organization operates, the fraudster may have to create a false purchase order from the “buyer,” a false sales order, and a false invoice along with the packing slip to create the illusion of a sale.

The result is that a fake receivable account goes into the books for the price of the misappropriated inventory. Obviously, the “buyer” of the merchandise will never pay for it. How do fraudsters deal with these fake receivables? In some cases, the fraudster simply lets the receivable age on his company's books until it is eventually written off as uncollectable. In other instances the employee may take steps to remove the sale—and the delinquent receivable that results—from the books. For instance, in Case 1683, the perpetrator generated false invoices and delivered them to the company warehouse for shipping. The invoices were then marked “delivered” and sent to the sales office. The perpetrator removed all copies of the invoices from the files before they were billed to the fictitious customer. In other scenarios, the perpetrator might write the receivables off himself, as did a corrupt manager in Case 651; in a five-year scheme, the perpetrator took company assets and covered up the loss by setting up a fake sale. A few weeks after the fake sale went into the books, the perpetrator wrote off the receivable to an account for “lost and stolen assets.” More commonly, however, the fake sale will be written off to discounts and allowances or a bad debt expense account.

Instead of completely fabricated sales, some employees understate legitimate sales so that an accomplice is billed for less than is delivered. The result is that a portion of the merchandise is sold at no cost. For instance, in Case 998 a salesman filled out shipping tickets, which he forwarded to the warehouse. After the merchandise was delivered, he instructed the warehouse employees to return the shipping tickets to him for “extra work” before they went to the invoicing department. But the extra work the salesman did was simply to alter the shipping tickets, reducing the quantity of merchandise on the ticket so that the buyer (an accomplice of the salesman) was billed for less than he received.

The following case study was selected as an example of a false shipping scheme. In this case, a marketing manager, with the help of a shipping clerk, delivered several computer hard drives to a computer company in return for a substantial cash payment. The victim company in this case had poor controls that allowed merchandise to be shipped without receipts, leaving the company extremely vulnerable to such a scheme. Harry D'Arcy, CFE, investigated this crime and eventually helped bring the culprits to justice.

CASE STUDY: HARD DRIVES AND BAD LUCK2

Someone had stolen 1,400 hard drives from a computer ware-house in Toronto. That much was certain. But the question remained: who took them? The answer was more than academic; it could mean the difference between the distributor's continuing operation and a total crash. Swainler's Technology averaged $8–$9 million a year in sales, but with an 8 percent profit margin, the company didn't have much financial room to maneuver. The company was a joint venture, overseen by a group of investors who were, to put it mildly, nervous. They had theft insurance, but with a particularly sticky clause that said that the policy wouldn't cover theft committed by a Swainler's employee. In order to collect on the $600,000 worth of disk drives missing from the warehouse, the investors had to show that the theft was an outside job.

Their report showed just that. Employees and management agreed that the skids bearing the equipment had been safe and sound until the week that a competitor of Swainler's, Hargrove Incorporated, had sent delivery drivers over for an exchange. Evidently, some of Hargrove's people had swiped the equipment during the several days they were working in the Swainler's warehouse. Hargrove and Swainler's worked together when they had to, but they were in hot competition, and at different times each company had lost business—and employees—to the other. Since all Swainler's employees checked out, management concluded that the theft must have been committed by someone from Hargrove.

Doug Andrews was an independent adjuster hired by Swainler's Technology's insurance company. Besides conducting routine loss estimates, he's also a certified fraud examiner who is willing, as he puts it, “to see things other people either don't see or choose to ignore.” Although the Swainler's board assured Andrews this was a simple case, he wasn't convinced: “I wasn't sure it wasn't an inside job. Too many questions were left hanging. How did the Hargrove people get the stuff out without being seen? The date management was setting for the loss seemed awfully convenient. It seemed like at the least someone at Swainler's had to be involved,” Andrews remembers. He needed some help chasing down these hunches, so Andrews hired Harry D'Arcy to assist. D'Arcy worked for the Canadian Insurance Crime Prevention Bureau as a CFE and investigator. He and Andrews interviewed everyone at the warehouse and on the investors' board, returning two or three times if necessary to get their questions answered. They traced serial numbers and possible distribution routes to turn up some sign of the hard drives. D'Arcy says, “We met at least twice a week to come up with a way to solve this. It was like a think tank, bouncing ideas and options off each other: ‘What tack should we take now? Should we call out to California? Do we need to go to that shop in Ottawa?’ We knew we were being stymied. We just had to find a way around the blocks they put in front of us.”

The main thing bothering Harry D'Arcy was that the board was presenting them with what appeared to be an open and shut case. Everyone's stories matched like precision parts. “It was too good to be true, too neat,” D'Arcy says. The board members had seen the material on the Friday before Hargrove came; they noticed it was gone afterward; they had reason to suspect their competitor was behind it. Yes, they knew their insurance policy wouldn't pay if an employee did the hit, but that was beside the point. The board trusted its employees. Many of the people at Swainler's, from clerks to warehouse personnel, were either related to, or friends of, the management. D'Arcy and Andrews were encountering what Andrews later described as “an active campaign of misinformation.”

Once he got a sense of the system of operation at Swainler's, D'Arcy had some material for a new round of questioning. He noticed that as skids of equipment were prepared for shipping, the entire apparatus was wrapped in a thick plastic sealant and moved from the warehouse floor into the shipping dock. “Now,” he asked one of the investors, “if those disk drives were ready for shipping on the Friday you say, then they would have already been wrapped, right?”

“Sure.”

“Then, how did you know what you were seeing if the wrapping was already on? You can't see through the wrapping.”

“I knew that batch was supposed to go out for the next week,” the man replied.

“Then the skids should have been moved to the loading dock,” D'Arcy interjected.

“I don't see your point.”

“You said you saw them in the warehouse,” D'Arcy reminded the man. “You couldn't have seen them in the warehouse if they had been moved to the dock for shipping.” The witness, feeling stymied himself, shifted and said, “Well, maybe they hadn't been taken over yet.”

D'Arcy had a full house of questions for the initially talkative managers. Why would they notice a particular skid of drives on a particular day? Why were their memories so specific on this one shipment? How often did management tour the warehouse for an informal inventory? D'Arcy reports, “Once I had them shaken up, I would ask them point blank, ‘Are you parroting something you heard somebody else say?’” The men would declare that, no, they'd seen the material themselves.

“Did you discuss this with other board members?” D'Arcy asked.

“We talked about it in board meetings, sure,” came the answer.

“And did you all agree on what you would say when you gave a statement?”

“No.”

“But your statements all match.”

“We agreed that we remembered the drives being there on the same day.”

Doug Andrews was feeling fed up: “We were getting this string of nonanswers. I felt like we were coming up dry.”

Swainler's had hired a private investigator of its own to work the case. Harry D'Arcy talked with the man, who was convinced he had the material to show an outside job. The PI had been to Hargrove and spoken with employees there, including a man who had once worked for Swainler's. “I don't know if somebody here took the stuff or not,” the man said. “But those guys at Swainler's deserve everything they get.” He claimed Swainler's required its employees to work long hours with little pay or benefits, that workers were little more than switches on a processing board. To Swainler's investigator, then, this was a classic case of employee resentment, a common excuse for fraud.

D'Arcy said he disagreed, but the investigator persisted. Swainler's Technology was now claiming its expenses for the investigation, finally totaling $125,000. During one week alone, the PI billed $45,000 when he conducted a stakeout in another city. An anonymous tip to the executive vice president at Swainler's placed the stolen disks at a storage facility in London, Ontario. The investigator took a team of people and equipment, and after a weekend of surveillance, it observed a man opening the unit. When the team approached, it found nothing inside but the man's personal belongings.

Meanwhile, D'Arcy and Andrews pursued their own strategy. They notified the manufacturer's representatives throughout Canada and the United States to be on the lookout for a set of serial numbers. Sure enough, a call came in from a dealer in California; one of the disk drives had shown up for repair. Invoices showed the drive had been shipped from upstate New York and was purchased in Ottawa, Canada. The Ottawa shop had received the drive from a distributor in Montreal. Doug Andrews went to the Montreal warehouse but found it empty. Canvassing the neighborhood, he was told the people renting the warehouse had moved to another area in northern Montreal.

When Andrews got to the new address, he questioned four or five of the workers there about his case. They had never heard of Swainler's and knew nothing about the stolen drives. But when Andrews pressured them to look through their records with him, he found documents matching his serial numbers. Then, one of the missing drives turned up inside the warehouse.

Andrews wasn't ready to celebrate, though. “I was feeling beat. We'd been spending all this time, running back and forth, interviewing and reinterviewing. I said, ‘I don't know, we may not get this one.’” The invoices he'd looked at were dated five weeks earlier than the time Swainler's had listed the theft. The discrepancy might help disprove the company's outside perpetrator theory, but could also be used to throw Andrews's largely circumstantial case into further confusion. As he was driving back to Toronto, Andrews got a call from Harry D'Arcy. “I've been doing some work based on what you found there,” D'Arcy told him excitedly. “When you get back they'll be in chains.”

Since D'Arcy now knew that at least some of the merchandise had gone through the warehouse in Montreal, he had looked for phone calls from that city in the phone logs at Swainler's. The marketing manager, Frederic Boucher, had not only received a large number of calls from Montreal, the calls were coming from the warehouse Andrews had just visited, the one claiming it had never heard of Swainler's. D'Arcy spoke again with people in the warehouse, one of whom admitted that the skids had disappeared much earlier than first reported. He guessed the actual date was about a month earlier than the one management had given. This, of course, coincided with the invoices Andrews had found in Montreal. At a special meeting, the board of directors reviewed D'Arcy's findings and confronted Frederic Boucher with the evidence pointing toward him. Boucher denied any involvement, and the board supported his story.

The next morning, Boucher told a different story. He had talked with his wife and a lawyer and was ready to come clean. He said he'd met the people from the Montreal warehouse at a conference. Together they worked out a deal in which Boucher would provide them with a supply of hard drives at a sweet price. With the help of a Swainler's shipping clerk, Boucher sent sixty low-end drives to Kingston, halfway between Montreal and Toronto, for $20,000 paid in cash. The atmosphere at Swainler's was ripe for this sort of offense. Harry D'Arcy recalls, “The bookkeeping system wasn't controlled. It was nothing to find things going out with no receipts. The operation was mainly run on trust. The men who headed up the company were all old friends, and they hired people they knew or to whom they were connected in one way or another. It ran on blind trust and nepotism.” Encouraged by their first success, Boucher and his accomplices then arranged to make the big sale: 1,400 top-quality hard drives for a $600,000 take. They didn't have to worry about covering their tracks, because management was eager to point the finger outside the company and collect on their insurance.

With Boucher's confession, Doug Andrews could make a happy report to his client that they weren't liable for the claim. Boucher was sentenced to make restitution for the theft, and to two years' imprisonment, while the shipping clerk and the Montreal distributor were given one year each. All the sentences were suspended and the defendants placed on probation. The executives at Swainler's were, according to Harry D'Arcy, “cautioned regarding their complicity in the matter.” Swainler's survived the loss but was later purchased by a prominent Canadian investment group and now operates under that umbrella.

Doug Andrews, who lectures and writes articles on insurance fraud in addition to conducting investigations, finds that people resist seeing cases like Swainler's as a real crime.

“There's a belief that perpetrating fraud against an insurer is a victimless crime.” Reports from the KPMG accounting firm and the Canadian Coalition Against Insurance Fraud place the insurance losses in Canada between $1 billion and $2.6 billion a year. But Andrews believes that “[you can] take the middle figure of $2 billion and double it.” Though a significant portion of those losses is related to occupational crimes, an accurate account is not yet available. That's because some of the major acts that occur in business felonies—like supplier and kickback fraud—aren't included in the insurance industry figures. Nevertheless, these crimes are serious and proliferating. “They are frequent,” Andrews says, “and often systematic and well organized. Especially since insurance companies don't advertise as aggressively in Canada as they do in the United States, people see insurance as a kind of faceless bureaucracy.” With the tremendous amounts of money changing hands in this industry every day, “there's a mindset that labels these companies fair game. . . But people see the difference in the end, when they pay their premiums.”

Other Schemes

Because employees tailor their thefts to the security systems, record-keeping systems, building layout, and other day-to-day operations of their companies, the methods used to steal inventory and other assets vary. The preceding categories comprised the majority of schemes in our studies, but there were a couple of other schemes that did not fit any established category, yet that merit discussion.

Write-offs are often used to conceal the theft of assets after they have been stolen. In some cases, however, assets are written off in order to make them available for theft. In Case 894 a warehouse foreman abused his authority to declare inventory obsolete. He wrote off perfectly good inventory, then “gave” it to a dummy corporation that he secretly owned. This fraudster took over $200,000 worth of merchandise from his employer. Once assets are designated as “scrap,” it may be easier to conceal their misappropriation. Fraudsters may be allowed to take the “useless” assets for themselves, buy them or sell them to an accomplice at a greatly reduced price, or simply give the assets away.

One final unique example was presented in Case 2188. In this scheme a low-level manager convinced his supervisor to approve the purchase of new office equipment to replace existing equipment, which was to be retired. When the new equipment was purchased, the perpetrator took it home and left the existing equipment in place. His boss assumed that the equipment in the office was new, even though it was actually the same equipment that had always been there. If nothing else, this case illustrates that sometimes a little bit of attentiveness by management is all it takes to halt fraud.

CONCEALING INVENTORY SHRINKAGE

When inventory is stolen, the key concealment issue for the fraudster is shrinkage. Inventory shrinkage is the unaccounted-for reduction in the company's inventory that results from theft. For instance, assume that a computer retailer has 1,000 computers in stock. After work one day, an employee loads ten computers into a truck and takes them home. Now the company only has 990 computers, but since there is no record that the employee took ten computers, the inventory records still show 1,000 units on hand. The company has experienced inventory shrinkage in the amount of ten computers.

Shrinkage is one of the red flags that signal fraud. When merchandise is missing and unaccounted for, the obvious question is, “Where did it go?” The search for an answer to this question can uncover fraud. The goal of the fraudster is to proceed with his scheme undetected, so it is in his best interest to prevent anyone from looking for missing assets. This means concealing the shrinkage that occurs from theft.

Inventory is typically tracked through a two-step process. The first step, the perpetual inventory, is a running count that records how much should be on hand. When new shipments of supplies are received, for instance, these supplies are entered into the perpetual inventory. Similarly, when goods are sold, they are removed from the perpetual inventory records. In this way, a company tracks its inventory on a day-to-day basis.

Periodically, companies should make a physical count of assets on hand. In this process, someone actually goes through the storeroom or warehouse and counts everything that the company has in stock. This total is then matched to the amount of assets reflected in the perpetual inventory. A variation between the physical inventory and the perpetual inventory totals is shrinkage. While a certain amount of shrinkage may be expected in any business, large shrinkage totals may indicate fraud.

Altered Inventory Records

One of the simplest methods for concealing shrinkage is to change the perpetual inventory record so that it will match the physical inventory count. This is also known as a forced reconciliation of the account. Basically, the perpetrator just changes the numbers in the perpetual inventory to make them match the amount of inventory on hand. In Case 1465, a supervisor involved in the theft of inventory credited the perpetual inventory and debited the cost of sales account to bring the perpetual inventory numbers into line with the actual inventory count. Once these adjusting entries were made, a review of inventory would not reveal any shrinkage. Rather than use correcting entries to adjust perpetual inventory, some employees simply alter the numbers by deleting or covering up the correct totals and entering new numbers.

There are two sides to the inventory equation, the perpetual inventory and the physical inventory. Instead of altering the perpetual inventory, a fraudster who has access to the records from a physical inventory count can change those records to match the total of the perpetual inventory. Going back to the computer store example, assume that the company counts its inventory every month and matches it to the perpetual inventory. The physical count should come to 990 computers, since that is what is actually on hand. If the perpetrator is someone charged with counting inventory, he can simply write down that there are 1,000 units on hand.

Fictitious Sales and Accounts Receivable

We have already discussed how fraudsters create fake sales to mask the theft of assets. When the perpetrator made an adjusting entry to the perpetual inventory and cost of sales accounts in Case 1465, above, the problem was that there was no sales transaction on the books that corresponded to these entries. Had the perpetrator wished to fix this problem, he would have entered a debit to accounts receivable and a corresponding credit to the sales account to make it appear that the missing goods had been sold.

Of course, the problem of payment then arises, because no one is going to pay for the goods that were “sold” in this transaction. There are two routes that a fraudster might take in this circumstance. The first is to charge the sale to an existing account. In some cases, fraudsters charge fake sales to existing receivables accounts that are so large that the addition of the assets that the fraudster has stolen will not be noticed. Other corrupt employees charge the “sales” to accounts that are already aging and will soon be written off. When these accounts are removed from the books, the fraudster's stolen inventory effectively disappears.

The other adjustment that is typically made is a write-off to discounts and allowances or bad debt expense. In Case 2790, an employee with blanket authority to write off up to $5,000 in uncollectable sales per occurrence used this authority to conceal false sales of inventory to nonexistent companies. The fraudster bilked his company out of nearly $180,000 using this method.

Write Off Inventory and Other Assets

We have already discussed Case 894, in which a corrupt employee wrote off inventory as obsolete, then “gave” the inventory to a shell company that he controlled. Writing off inventory and other assets is a relatively common way for fraudsters to remove assets from the books before or after they are stolen. Again, this is beneficial to the fraudster because it eliminates the problem of shrinkage that inherently exists in every case of noncash asset misappropriation. Examples of this method include Case 705, in which a manager wrote supplies off as lost or destroyed, then sold the supplies through his own company; and Case 720, in which a director of maintenance disposed of fixed assets by reporting them as broken, then took the assets for himself.

Physical Padding

Most methods of concealment deal with altering inventory records, either by changing the perpetual inventory or by miscounting during the physical inventory. As an alternative, some fraudsters try to make it appear that there are more assets present in the warehouse or stockroom than there actually are. Empty boxes, for example, may be stacked on shelves to create the illusion of extra inventory. In Case 5, for example, employees stole liquor from their stockroom and restacked the containers for the missing merchandise. This made it appear that the missing inventory was present when in fact there were really empty boxes on the stockroom shelves. In a period of approximately eighteen months, this concealment method allowed employees to steal over $200,000 of liquor.

The most egregious case of inventory padding in our studies occurred in Case 1666, in which the fraudsters constructed a facade of finished product in a remote location of a warehouse and cordoned off the area to restrict access. Though there should have been a million dollars' worth of product on hand, there was actually nothing behind the wall of finished product, which was constructed solely to create the appearance of additional inventory.

PREVENTING AND DETECTING THEFTS OF NONCASH TANGIBLE ASSETS THAT ARE CONCEALED BY FRAUDULENT SUPPORT

In the purchasing function, it is important to separate the duties of ordering goods, receiving goods, maintaining perpetual inventory records, and issuing payments. Invoices should always be matched to receiving reports before payments are issued in order to help prevent schemes where inventory is stolen from incoming shipments.

To prevent fraudulent shipments of merchandise, organizations should make sure that every packing slip (sales order) is matched to an approved purchase order and that every outgoing shipment is matched to the sales order before the merchandise goes out. Shipments of inventory should be periodically matched to sales records to detect signs of fraud. Whenever a shipment shows up that cannot be traced to a sale, this should be investigated. Another red flag that may indicate a fraudulent shipping scheme is an increase in bad debt expense. As was discussed earlier, some employees will create a fraudulent sale to justify a shipment of merchandise, then will either cancel the sale or write it off as a bad debt after the goods have left the victim organization. Customer shipping addresses can also be matched against employee addresses to find schemes in which an employee has inventory or equipment delivered to his home address.

Carefully review any unexplained entries in perpetual inventory records. Make sure all reductions to the perpetual inventory records are supported by proper source documents. Look for obvious signs of alterations. Make sure that the beginning balance for each month's inventory ties to the ending balance from the previous month. Also determine that the dollar value of ending inventory is reasonably close to previous comparable amounts. Reconcile the inventory balance on the inventory report to the inventory balance in the general ledger. Investigate any discrepancies.

Another fairly common scheme involves employees who overstate the amount of materials needed for a project and steal the excess materials. To prevent this kind of fraud, organizations should reconcile materials ordered for projects to the actual work done. Make sure all materials requisitions are approved by appropriate personnel and require both the requestor and the approver to sign materials requisitions so that if fraud occurs, the culprit can be identified.

In some circumstances employees will write off stolen inventory or equipment as “scrap” either to make it easier to steal (because the organization has fewer safeguards over its scrap items) or to account for the missing assets on the organization's books. In either case, organizations should periodically perform trend analysis on the amount of inventory that is being designated as scrap. Significant increase in scrap levels could indicate an inventory theft scheme. Similarly, look for unusually high levels of reorders for particular items, which could indicate that a particular item of inventory is being stolen.

Assets should be removed from operations only with the proper authority. For example, if a journal entry is used to record abandonment of a fixed asset, the journal entry should be supported by the responsible person's approval. Control should be maintained over assets during disposal. If the organization sells assets that have been designated as scrap, they should be turned over to the selling agent on approval of the disposal. The asset custodian should maintain contact with the selling agent to report on the disposition of the asset in question. Proceeds from the sale of scrap items should follow normal cash receipt operations. The person responsible for asset disposition should not be responsible for receipt of the proceeds.

MISAPPROPRIATION OF INTANGIBLE ASSETS

Misappropriation of Information

In addition to misappropriation of tangible noncash assets, organizations are vulnerable to theft of proprietary information, which can undermine their value, reputation, and competitive advantages, and result in legal liabilities. According to the ACFE 2011 Global Fraud Survey, fraudsters misappropriated information in 19 percent of the cases involving noncash misappropriations.

Companies frequently make sizeable technological investments in protecting their information from external information thieves, but often the biggest threats are internal. Employees are the most likely to be in a position to exploit their employers' information security. After all, who has more insider information and access to proprietary records and data than an employee or former employee?

Information misappropriation schemes commonly include theft by employees of competitively sensitive information, such as customer lists, marketing strategies, trade secrets, new products, or details on development sites. For example, in Case 5565, an employee who felt a sense of entitlement for having contributed to a new product design stole the design in an attempt to get ahead in a new job with a competitor. And in Case 5582, a disgruntled former employee sold a company trade secret to a competitor in order to retaliate for what he felt was unfair treatment.

It is critical that companies identify their most valuable information and take steps to protect it. This process must be a cross-departmental endeavor involving specialists from corporate security/risk management, information technology, human resources, marketing, research and development, and so on. If in-house capabilities do not exist, companies can bring in information security experts to assist them in designing an effective information security system, including awareness training for employees. An information security system may include measures such as limiting access to networks, systems, or data to those who have a legitimate need for access, protecting company data through the use of firewalls and virus scanning software, implementing and enforcing confidentiality agreements and restrictive covenants where appropriate, performing adequate background checks on employees, establishing and enforcing a security policy, and much more.

Misappropriation of Securities

According to the ACFE 2011 Global Fraud Survey, although securities were the least likely asset to be misappropriated (8 percent of cases), the median loss in cases involving securities theft was higher than in any other category, at $330,000 (see Exhibit 9-4 and 9-5). In order to avoid falling victim to a misappropriation of securities scheme, companies must maintain proper internal controls over their investment portfolio, including proper separation of duties, restricted access to investment accounts, and periodic account reconciliations.

In Case 5234, the director of accounting and finance, who was responsible for making trades, left his computer unattended for a short time while signed into one of the company's investment accounts. Another employee, a senior accountant, took the opportunity to access the director's computer to sell $15,000 worth of investments and have the proceeds mailed to the company. Due to lax internal controls, she was able to intercept the check and deposit it into her own bank account. Because this employee was in charge of reconciling the investment accounts and had the access needed to enter and post journal entries to the general ledger, she was able to easily hide her scheme by writing off a “loss” on investments to an expense account. It wasn't until almost a year later, when auditors were reviewing the company's books, that the scheme was uncovered. By that time, the thief was nowhere to be found.

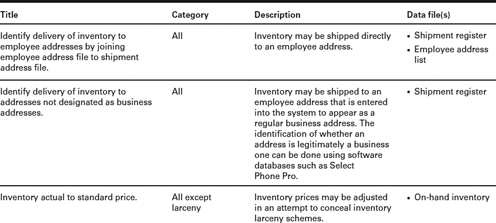

PROACTIVE COMPUTER AUDIT TESTS FOR DETECTING NONCASH MISAPPROPRIATIONS1

SUMMARY

Asset misappropriation schemes are subdivided based on whether the perpetrator steals cash or noncash assets such as inventory, supplies, equipment, information, and securities. As the data from the 2011 Global Fraud Survey show, noncash schemes are less common than cash schemes, and the median loss in noncash schemes is slightly lower.

In this chapter, we discussed five types of schemes used to misappropriate noncash tangible assets: misuse, unconcealed larceny, asset requisitions and transfers, purchasing and receiving schemes, and fraudulent shipments. Misuse schemes occur when an employee makes an unauthorized use of his organization's property without actually stealing the property. Unconcealed larceny, as its name implies, involves the theft of noncash assets without the use of fraudulent bookkeeping entries to conceal the theft.

Fraudulent asset requisitions and transfers schemes involve the use of internal documents to cause inventory, supplies, or equipment to be moved from one location to another or allocated to a particular project. These documents do not necessarily account for missing property, but they enable the perpetrator to gain access to and transport the property and thus provide an opportunity to steal it.

In purchasing and receiving schemes, an employee steals incoming merchandise by fraudulently marking incoming shipments as “short” to conceal the theft. Fraudulent shipments are a category of noncash theft in which a fraudster causes his organization to ship out merchandise as though it had been sold. The shipments are typically sent to the perpetrator or an accomplice.

The key concealment issue for a fraudster in a noncash theft case is shrinkage, which may be defined as the unaccounted-for reduction in an organization's inventory that results from theft. Inventory shrinkage is generally concealed on the victim organization's books through the alteration of inventory records (either manually or by false entry), the creation of fictitious sales and receivables, the fraudulent writing off of noncash assets as “scrap,” or physical padding (in which empty boxes or containers are used to create the appearance of extra inventory on hand).

We also addressed misappropriation of intangible asset schemes, specifically the misappropriation of information and securities. Because theft of company information—including customer information, trade secrets, new product designs, and marketing plans—can undermine a company's value, reputation, and competitive advantages, the information must be protected through an effective information security system. In addition, companies must maintain proper internal controls to protect their securities and other noncash investments from misappropriation.

ESSENTIAL TERMS

Larceny Schemes in which an employee steals an asset without attempting to conceal the theft in the organization's books and records.

Fraudulent write-offs A method used to conceal the theft of noncash assets by justifying their absence on the books. Stolen items are removed from the accounting system by being classified as scrap, lost or destroyed, damaged, bad debt, scrap shrinkage, discounts and allowances, returns, and so forth.

Shrinkage The unaccounted-for reduction in an organization's inventory that results from theft. Shrinkage is a common red flag of fraud.

Perpetual inventory A method of accounting for inventory in the records by continually updating the amount of inventory on hand as purchases and sales occur.

Physical inventory A detailed count and listing of assets on hand.

Forced reconciliation A method of concealing fraud by manually altering entries in an organization's books and records or by intentionally miscomputing totals. In the case of noncash misappropriations, inventory records are typically altered to create a false balance between physical and perpetual inventory.

Physical padding A fraud concealment scheme in which the fraudsters try to create the appearance that there are more assets on hand in a warehouse or stockroom than there actually are (e.g., by stacking empty boxes to create illusion of extra inventory).

REVIEW QUESTIONS

9-1 (Learning objective 9-1) What are the five categories of schemes used to misappropriate noncash tangible assets identified in this chapter?

9-2 (Learning objective 9-2) According to the 2011 Global Fraud Survey, how do noncash misappropriations compare with cash misappropriations in terms of frequency and cost? What two types of noncash assets were most commonly misappropriated?

9-3 (Learning objective 9-3) What are some examples of asset misuse? Give at least three.

9-4 (Learning objective 9-4) What is an unconcealed larceny scheme?

9-5 (Learning objective 9-6) Able is a job-site supervisor for ABC Construction. Able is responsible for overseeing the construction of a number of residential homes and for making sure each of his crews has sufficient materials to complete its work. All of ABC's lumber and other building materials are stored in a central warehouse and are released upon signed authorization from job-site supervisors as needed. Able requests twice the amount of lumber that is actually needed for a particular job. He uses the excess materials to build a new deck on his home. How would Able's scheme be categorized?

9-6 (Learning objective 9-9) What is shrinkage?

9-7 (Learning objectives 9-8 and 9-10) Baker works in the sales department of ABC Company, which manufactures computer chips. Baker creates false documentation indicating that XYZ, Inc. (a nonexistent company) has agreed to purchase a large quantity of computer chips. The computer chips are shipped to XYZ, Inc. “headquarters,” which is really Baker's house. How would Baker's scheme be categorized, and what are some red flags that might occur as a result of the scheme?

9-8 (Learning objective 9-7) How do employees use falsified receiving reports as part of schemes to steal inventory?

9-9 (Learning objective 9-10) What is meant by the term physical padding?

9-10 (Learning objective 9-10) What are the four methods identified in this chapter by which employees conceal inventory shrinkage?

9-11 (Learning objective 9-11) Provide an example of a misappropriation of intangibles scheme.

DISCUSSION ISSUES

9-1 (Learning objective 9-3) Jones is the manager of ABC Auto Repair. Unknown to his employer, Jones also does freelance auto repair work to earn extra cash. He sometimes uses ABC's facilities and tools for these jobs. Discuss the costs and potential costs that ABC might suffer as a result of Jones's actions.

9-2 (Learning objectives 9-4 and 9-5) Discuss how establishing a strong system of communication between employees and management can help deter and detect inventory larceny.

9-3 (Learning objectives 9-5 and 9-6) In the case study “Chipping Away at High-Tech Theft,” do you believe the procedures and controls maintained by the manufacturer contributed to the theft? Why, or why not?

9-4 (Learning objective 9-5) Discuss the controls that an organization should have in place to effectively prevent and detect larceny of inventory.

9-5 (Learning objective 9-7) Baker was in charge of computer systems for ABC Company. As part of a general upgrade, the company authorized the purchase of twenty new computers for the employees in its marketing department. Baker secretly changed the order so that twenty-one computers were purchased. When they were delivered, he stole the extra computer. Later, ten more new computers were purchased for the ten employees in the company's research and development department. Baker also stole one of these computers. How should these two schemes be classified under the fraud tree?

9-6 (Learning objectives 9-8 and 9-12) Baker is an auditor for ABC Company. As part of a proactive fraud audit, Baker runs the following tests: (1) a review of the sales register for dormant customer accounts that posted a sale within the last two months; and (2) a comparison of the sales register and the shipment register for shipping documents that have no associated sales order. Taken together, what type of noncash scheme is Baker most likely to find with these tests? Explain how each one might identify fraud.

9-7 (Learning objective 9-8) Explain why the following circumstances might indicate that one or more employees are stealing merchandise: (1) an increase in uncollectable sales from previous periods and (2) an increase in damaged or obsolete inventory from previous periods.

ENDNOTE

1Several names and details have been changed to preserve anonymity.

*The sum of these percentages exceeds 100 percent because some cases involved multiplefraud schemes that fell into more than one category. Similarly, other charts in this chapter may also reflect percentages totaling in excess of 100 percent.

2Several names and details have been changed to preserve anonymity.

1. Lanza, pp. 41–44.