LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

| 7-1 | Explain what constitutes expense reimbursement fraud |

| 7-2 | Discuss the data on expense reimbursement fraud from the 2011 Global Fraud Survey |

| 7-3 | Understand how mischaracterized expense reimbursement schemes are committed |

| 7-4 | Be familiar with the controls identified in this chapter for preventing and detecting mischaracterized expense schemes |

| 7-5 | Identify the methods employees use to overstate otherwise legitimate expenses on their expense reports |

| 7-6 | Understand controls that can be used to prevent and detect overstated expense schemes |

| 7-7 | Explain what a fictitious expense reimbursement scheme is and differentiate it from other forms of expense reimbursement fraud |

| 7-8 | Identify red flags that are commonly associated with fictitious expense schemes |

| 7-9 | Discuss what a multiple reimbursement scheme is and how this kind of fraud is committed |

| 7-10 | Discuss the controls identified in this chapter for preventing and detecting multiple reimbursement schemes |

| 7-11 | Be familiar with proactive audit tests that can be used to detect various forms of expense reimbursement fraud |

CASE STUDY: FREQUENT FLIER'S FRAUD CRASHES1

In his ten years at a regional office of Tyler & Hartford, Marcus Lane had spent more time on the road than at home—which means he often whispered a long-distance goodnight to his kids over his cell phone. The 35-year-old Ph.D. traveled all over North and South America for his job as a geologist for the privately held firm specializing in environmental management and engineering services. Its extensive client list represented all types of industries and included municipalities, construction firms, petroleum companies, and manufacturers with multimillion-dollar projects. As part of a team assembled by a project manager from Tyler & Hartford, Lane was regularly called on to oversee drilling operations, conduct sampling tests, or assist with a formal site analysis.

Going from site to site, the road warrior adhered to the basic rules of business travel: Try to get a room on the top floor, away from the elevators and the ice machine. Request a seat in an emergency exit row on the airplane, where there is more leg room. Always get documentation for any travel expense—and so on. But Lane broke a basic rule of ethics: never cheat on your expense report.

His transgression was discovered by Heidi McCullough, an accountant who worked out of Tyler & Hartford's East Coast headquarters. As she was processing Lane's most recent expense report, she noticed a discrepancy between the departure times listed on the flight receipt and boarding pass for Flight 4578 from Minneapolis to San Antonio. Whereas the receipt indicated that the flight had been scheduled to depart at 6:15 p.m., the boarding pass indicated a departure time of 6:15 a.m. McCullough figured that the discrepancy was most likely due to an error on the part of the airline. After all, Lane was a highly trusted and well respected employee who traveled regularly on company business. But, being the prudent employee she was, she decided she'd better bring the discrepancy to the attention of Tina Marie Williams, manager of the internal audit department.

“I was immediately suspicious,” recalled Williams, who was newly accredited as a CFE at the time. “Although it was possible that the airline had made an error, it seemed much more likely that either the flight receipt, the boarding pass, or both had been doctored. This was a situation that needed to be looked into.” The first thing Williams did was contact the airline to verify whether the flight number in question was even a legitimate flight, and, if so, what the correct scheduled departure time was. She learned that flight 4578 was, in fact, an actual flight and that it had been scheduled to depart—and did depart—at 6:15 p.m. But because Lane had booked the flight using his own credit card, she was unable to confirm with the airline whether he actually took the flight.

Next Williams proceeded to carefully review the rest of the Lane's travel receipts for his trip to San Antonio. Two of the receipts stood out. One was for a car rental, which indicated that the car was picked up by Lane at noon on the day of his flight to San Antonio. The second was a receipt for lunch at a restaurant located near the San Antonio International Airport, also on the day of the flight.

Williams suspected that Lane had not actually boarded flight 4578, but had created a phony boarding pass to make it appear as though he had. As an experienced auditor, Williams was familiar with a common expense reimbursement scheme in which an employee books two separate flights to the same location, but with a huge cost difference; he uses the cheaper ticket for the actual flight and returns the more expensive ticket for credit. And, of course, he submits the more expensive ticket for reimbursement.

“Company policy is that employees must book all travel through the company travel agent. But Lane has been booking his own travel since long before I started working here. When I mentioned my concerns over this to senior management I was told to let it be—that Lane was a loyal and trustworthy employee, and that I had nothing to worry about.”

Playing by the book, Williams called the legal department at Tyler & Hartford to apprise it of the situation and ask for any advice on procedure. Williams said that the legal department put the case under protective privilege.

She then overnighted her collection of evidence along with her detailed analysis of the airfare scheme to Lane's immediate supervisor at the regional office, who in turn showed it to his boss at his earliest availability. Right on time, the two managers scheduled a private meeting with Lane, bright and early on the following Monday morning.

Without mincing words, one of the managers asked Lane, “How is it that you were able to pick up a rental car at noon and have lunch in San Antonio when your flight from Minneapolis didn't depart until 6 p.m.?” Lane, knowing that he had been caught, immediately confessed to double-booking flights and creating fictitious boarding passes using his home computer, in order to make it appear as though he took a more expensive flight than he had actually taken. He explained that he was experiencing temporary financial problems as the result of his recent divorce, that he just needed some money to tide him over. He said that he intended to pay the money back as soon as possible. According to Williams, who heard the account second-hand, Lane vowed, “I only did it for four months.” He swore that he padded his expense account for just a brief period; he urged the managers to check out all the other expense reports he had submitted in his ten years at Tyler & Hartford and voluntarily agreed to surrender his personal credit card and bank records. He also agreed to provide his own accounting of the crime.

All in all, Lane had swindled the company out of $4,100. He agreed to pay back the stolen money. “He paid us $2,000 in one lump sum initially, then $150 every two months after that,” Williams recalled.

Lane was promptly terminated, but Tyler & Hartford decided not to prosecute the geologist. They kept their month-long investigation quiet as well. “No one found out about it except through the grapevine.” Even then, others only knew that somebody got in trouble for fudging an expense report, said Williams.

True to the company's culture of taking decisive action, Williams and her team resolved this case in just under one month from the time of its detection. “This is the smoothest case we've ever had,” she admitted.

“We discovered that it was a very easy fraud to perpetrate, especially since it is so simple to create phony airline tickets and boarding passes. On behalf of Tyler & Hartford, Williams later launched a target audit to uncover other travel scams, and found some. Lane's scam, unfortunately, was not an isolated incident.

After Lane's fraud was exposed, Williams received full support from senior management for clarification and better enforcement of the policy that all travel for the entire company, including all fifty regional offices, must be booked through the company travel agent using a designated company credit card. “That makes our auditing lives so much easier. It gives us better control, as well as better cost data,” said Williams.

Williams also recommended that employees only use a company credit card to charge all other business expenditures. Top management accepted the recommendation and issued a mandate. Williams was pleased, as the billing statement for a company credit card provides a strong audit tool and an easy-access audit trail.

OVERVIEW

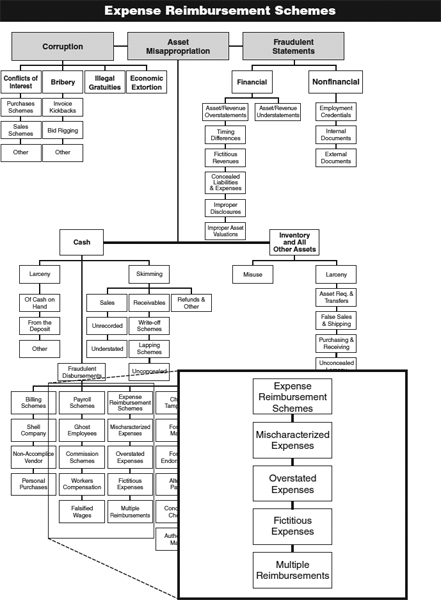

Expense reimbursement schemes are a form of fraudulent disbursement that, as the name implies, occur when employees make false claims for reimbursement of fictitious or inflated business expenses (see Exhibit 7-1). This is a very common form of occupational fraud and one that, by its nature, can be extremely difficult to detect. Employees who engage in this type of fraud generally seek to have the company pay for their personal expenses, or they pad the amount of business expenses they have incurred in order to generate excess reimbursements. In most cases, the travel and entertainment expenses at issue were incurred away from the office where there was no direct supervision and no company representative (other than the fraudster) present to verify that the expenses were, indeed, incurred. Thus, these frauds generally are detected through indirect means—trend analysis, comparisons of expenses to work schedules, and so forth. If a fraudster is smart and does not get too greedy, it can be virtually impossible to catch an expense reimbursement scheme. But then, most fraudsters eventually get greedy.

Expense Reimbursement Data from the ACFE 2011 Global Fraud Survey

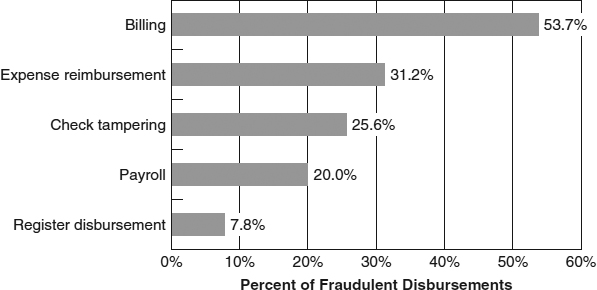

In the ACFE's study, expense reimbursement fraud was cited in 31 percent of fraudulent disbursement cases, ranking second in terms of frequency (see Exhibit 7-2). In contrast, expense reimbursement fraud schemes were the second least costly form of fraudulent disbursement in the study, resulting in a median loss of $26,000 (see Exhibit 7-3).

EXPENSE REIMBURSEMENT SCHEMES

Expense reimbursements are usually paid by organizations in the following manner. An employee submits a report detailing an expense incurred for a business purpose, such as a business lunch with a client, airfare, hotel bills associated with business travel, and so on. In preparing an expense report, an employee usually must explain the business purpose for the expense, as well as the time, date, and location in which it was incurred. Attached to the report should be support documentation for the expense—typically, a receipt. In some cases, canceled checks written by the employee, or copies of a personal credit card statement showing the expense, are allowed. The report usually must be authorized by a supervisor in order for the expense to be reimbursed.

EXHIBIT 7-2 2011 Global Fraud Survey Frequency of Fraudulent Disbursements*

EXHIBIT 7-3 2011 Global Fraud Survey: Median Loss of Fraudulent Disbursements

There are four methods by which employees typically abuse this process to generate fraudulent reimbursements:

- Mischaracterized expense reimbursements

- Overstated expense reimbursements

- Fictitious expense reimbursements

- Multiple reimbursements

Mischaracterized Expense Reimbursements

Most companies reimburse only certain expenses of their employees. Which expenses a company will pay depends to an extent on policy, but in general, business-related travel, lodging, and meals are reimbursed. One of the most basic expense schemes is perpetrated by simply requesting reimbursement for a personal expense, claiming that it is business-related (see Exhibit 7-4). Examples of mischaracterized expenses include claiming personal travel as a business trip, listing dinner with a friend as “business development,” and so on. Fraudsters may submit the receipts from their personal expenses along with their reports and provide business reasons for the incurred costs.

The false expense report induces the victim company to issue a check, reimbursing the perpetrator for his personal expenses. A mischaracterization is a simple scheme. In cases involving airfare and overnight travel, a mischaracterization can sometimes be detected by simply comparing the employee's expense reports to his work schedule. Often, the dates of the so-called business trip coincide with a vacation or day off. Detailed expense reports allow a company to make this kind of comparison and are therefore very helpful in preventing expenses schemes.

Requiring detailed information means more than just supporting documents; it should mean precise statements of what was purchased, as well as when and where. In Case 479, a fraudster submitted credit card statements as support for expenses, but he submitted only the top portion of the statements, not the portion that describes what was purchased. Over 95 percent of his expenses that were reimbursed were of a personal rather than a business nature. Of course, in this particular example the scheme was made easier because the perpetrator was the CEO of the company, making it unlikely that anyone would challenge the validity of his expense reports.

EXHIBIT 7-4 Mischaracterized Expenses

Interestingly, many mischaracterized expense schemes are undertaken by high-level employees, owners, or officers. Many times, such a perpetrator actually has authority over the account from which expenses were reimbursed. In other cases, the perpetrators simply fail to submit detailed expense reports or even any expense reports at all. Obviously, when a company is willing to reimburse employee expenses without any verifying documentation, it is easy for an employee to take advantage of the system. Nevertheless, there does not seem to be anything inherent in the nature of a mischaracterization scheme that would preclude its use in a system in which detailed reports are required. As an example, suppose a traveling salesman goes on a trip and runs up a large bar bill one night in his hotel, saves his receipt, and lists this expense as “business entertainment” on an expense report. Nothing about the time, date, or nature of the expense would readily point to fraud, and the receipt would appear to substantiate the expense. Short of contacting the client who was allegedly entertained, there is little hope of identifying the expense as fraudulent.

One final note is that mischaracterization schemes can be extremely costly. They do not always deal with a free lunch here or there, but instead may involve very large sums of money. In Case 2249, for example, two mid-level managers ran up $1 million in inappropriate expenses over a two-year period. Their travel was not properly overseen, and their expense requests were not closely reviewed, allowing them to spend large amounts of company money on international travel, lavish entertainment of friends, and the purchase of expensive gifts. They simply claimed that they incurred these expenses entertaining corporate clients. Though this was more costly than the average mischaracterization scheme, it should underscore the potential harm that can occur if the reimbursement process is not carefully attended to.

Preventing and Detecting Mischaracterized Expense Reimbursements

Expense reimbursement fraud is very common and can be difficult to detect. It is important for organizations to focus on preventing these crimes by establishing and adhering to a system of controls that makes fraud more difficult to commit. As a starting point, every organization should require detailed expense reports that include original support documents, dates and times of business expenses, method of payment, and descriptions of the purpose for the expenses. All travel and entertainment expenses should be reviewed by a direct supervisor of the requestor. In no circumstance should expenses be reimbursed without an independent review.

Organizations should establish a policy that clearly states what types of expenses will and will not be reimbursed, that explains what are considered invalid reasons for incurring business expenses, and that sets reasonable limits for expense reimbursements. This policy must be publicized to all employees, particularly those who are likely to incur travel and entertainment expenses, and employees should sign a statement acknowledging that they understand the policy and will abide by it. This serves two purposes: first, it educates employees about what are considered acceptable reimbursable expenses; second, in the event that an employee tries to claim reimbursement for personal or nonreimbursable expenses, the signed statement will provide evidence that the employee knew the company's rules, which will help establish that the expense report in question was intentionally fraudulent, not the result of an honest mistake.

In some cases, fraud perpetrators try to get personal expenses approved by having their expense reports reviewed by a supervisor outside their department. The idea is that these supervisors will not be as familiar with the employee's work schedule, duties, and so on, so, for instance, if the perpetrator is claiming expenses for dates when she was on vacation, a direct supervisor might spot this anomaly, but a supervisor from another department might not. Therefore, organizations should scrutinize any expense report that was approved by a supervisor outside the requestor's department.

Because so many mischaracterized expense schemes involve personal expenses incurred during nonwork hours, one way to catch these crimes is to compare dates of claimed expenses to work schedules. For example, an organization could set up its accounting system so that any payment coded as an expense reimbursement is automatically compared to vacation or leave time requested by the employee in question. Expenses incurred on weekends or at unusual times could also be flagged for follow-up.

Organizations can also use trend analysis to detect these frauds. Current expense reimbursement levels should be compared to prior years and to budgeted amounts. If travel and entertainment expenses seem to be excessive, attempt to identify any legitimate business reasons for the increase. Also compare expense reimbursements per employee looking for a particular individual whose expense reimbursements seem excessive.

Overstated Expense Reimbursements

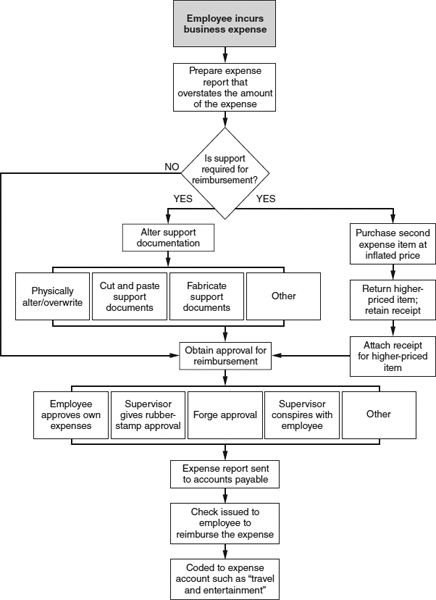

Instead of seeking reimbursement for personal expenses, some employees overstate the cost of actual business expenses (see Exhibit 7-5). This can be accomplished in a number of ways.

Altered Receipts The most fundamental example of overstated expense schemes occurs when an employee doctors a receipt or other supporting documentation to reflect a higher cost than what he actually paid. The employee may use correction fluid, a ball-point pen, or some other method to change the price reflected on the receipt before submitting his expense report. If the company does not require original documents as support, the perpetrator generally attaches a copy of the receipt to his expense report. (Alterations are usually less noticeable on a photocopy than on an original document.) For precisely this reason, many businesses require original receipts and ink signatures on expense reports.

As with other expense frauds, overstated expense schemes often succeed because of poor controls. In companies in which supporting documents are not required, for example, fraudsters simply lie about how much they paid for a business expense. With no support available, it may be very difficult to disprove an employee's false expense claims.

Overpurchasing The case of Marcus Lane at the beginning of this chapter illustrated another way to overstate a reimbursement form: the “overpurchasing” of business expenses. As we saw, Lane purchased two tickets for his business travel, one expensive and one cheap. He returned the expensive ticket, but used the receipt for it, along with a phony boarding pass, to overstate his expense report. Meanwhile, he used the cheaper ticket for his trip. In this manner, he was able to be reimbursed for an expense that was larger than what he had actually paid.

Overstating Another Employee's Expenses Overstated expense schemes are not only committed by the person who incurs the expense. In addition, they may be committed by someone else who handles or processes expense reports. Such an example occurred in Case 2389, where a petty cashier whited-out other employees' requests for travel advances and inserted larger amounts. The cashier then passed on the legitimate travel advances and pocketed the excess.

This kind of scheme is most likely to occur in a system in which expenses are reimbursed in currency rather than by a check, since the perpetrator would be unable to extract her “cut” from a single check made out to another employee.

Orders to Overstate Expenses Finally, AFCE researchers have seen a few cases in which employees knowingly falsified their own reports, but did so at the direction of their supervisors. In Case 1971, for instance, a department head forced his subordinates to inflate their expenses and return the proceeds to him. The employees went along with this scheme, presumably for fear of losing their jobs. The fraud lasted for 10 years and cost the victim company approximately $6 million. Similarly, in Case 1974, a sales executive instructed his salesmen to inflate their expenses in order to generate cash for a slush fund that was then used to pay bribes and to provide improper forms of entertainment for clients and customers.

EXHIBIT 7-5 Overstated Expenses

Preventing and Detecting Overstated Expense Reimbursement Schemes In addition to the prevention and detection methods that have already been discussed, it is particularly important, for dealing with overstated expense reimbursement schemes, that an organization require original receipts for all expense reimbursements. Alterations to original receipts should be very obvious, whereas it can be difficult to detect alterations to photocopies. Any policy addressing expense reimbursements should clearly state that expenses will be reimbursed only when supported by original receipts.

Comparison reports that show reimbursed expenses can be useful in detecting overstated expense reimbursement schemes. If one employee's travel and entertainment expenses are consistently higher than those of coworkers who have similar travel schedules, this is a red flag. Also, a comparison of similar expenses incurred by different individuals may highlight fraud. For example, if two salespeople regularly fly to the same city, does one tend to seek higher levels of reimbursement?

If an organization has had problems with expense reimbursement fraud, it may be helpful to spot-check expense reports with customers, confirming business dinners, meetings, and so forth.

Fictitious Expense Reimbursement Schemes

Expense reimbursements are sometimes sought by employees for wholly fictitious items. Instead of overstating a real business expense or seeking reimbursement for a personal expense, an employee simply invents a purchase to be reimbursed (see Exhibit 7-6).

Producing Fictitious Receipts One way to generate a reimbursement for a fictitious expense is to create bogus support documents, such as false receipts. Personal computers enable employees to create realistic-looking counterfeit receipts at home. Such was the scheme in Case 1275, in which an employee manufactured fake receipts using his computer and laser printer. The counterfeits were very sophisticated, even including the logos of the stores where he had allegedly made business-related purchases.

Computers are not the only means for creating support for a fictitious expense. The fraudster in Case 1275 used several methods for justifying fictitious expenses as his scheme progressed. He began by using calculator printouts to simulate receipts, then advanced to cutting and pasting receipts from suppliers before finally progressing to using computer software to generate fictitious receipts.

Obtaining Blank Receipts from Vendors If receipts are not created by the fraudster, they can be obtained from legitimate suppliers in a number of ways. A manager in Case 2830 simply requested blank receipts from waiters, bartenders, and so on. He then filled in these receipts to “create” business expenses, including the names of clients whom he allegedly entertained. The fraudster usually paid all his expenses in cash to prevent an audit trail. One thing that undid this culprit was the fact that the last digit on most of the prices on his receipt was usually a zero or a five. This fact, noted by an astute employee, raised questions about the validity of his expenses.

A similar scheme was found in Case 1980, in which an employee's girlfriend worked at a restaurant near the victim company. This girlfriend validated credit card receipts and gave them to the fraudster so that he could submit them with his expense reports.

Instead of asking for blank receipts, some employees simply steal them. In some cases a fraudster will steal an entire stack of blank receipts and submit them over time to verify fictitious business expenses. This type of fraud should be identifiable by the fact that the perpetrator is submitting consecutively numbered receipts from the same establishment even though his expense reports are spread out over time.

EXHIBIT 7-6 Fictitious Expenses

Claiming the Expenses of Others Another way that fraudsters use actual receipts to generate unwarranted reimbursements is by submitting expense reports for expenses that were paid by others. For instance, in Case 2619 an employee claimed hotel expenses that had actually been paid by his client. Photocopies of legitimate hotel bills were attached to the expense report as though the employee had paid for his own room.

As we have stated, not all companies require receipts to be attached to expense reports. Checks written by the employee or copies of his personal credit card bill might be allowed as support in lieu of a receipt. In Case 2075 a person wrote personal checks that appeared to be for business expenses, then photocopied these checks and attached them to reimbursement requests. In actuality, nothing was purchased with the checks; they were destroyed after the copies were made. This enabled the fraudster to receive a reimbursement from his employer without ever actually incurring a business expense. The same method can be used with credit cards, when a copy of a statement is used to support a purchase. Once the expense report is filed, the fraudster returns the item and receives a credit to his account.

In many expense reimbursement schemes the perpetrator is not required to submit any support at all. This makes it much easier to create the appearance of an expense that does not actually exist.

Preventing and Detecting Fictitious Expense Reimbursement Schemes A number of red flags may indicate an employee is seeking reimbursement for fictitious travel and entertainment expenses. One of the most common is the employee who claims items—particularly high-dollar items—were paid for in cash. This enables him to explain why there is no audit trail for the expense (i.e., why the item did not show up on his company credit card statement). Organizations should be alert for patterns in which an employee uses credit cards for low-dollar expenses but pays cash for high-dollar expenses. Other common red flags include the following:

- Expenses that are consistently rounded off, ending with a “0” or a “5,” which tends to indicate that the employee is fabricating the numbers

- Patterns in which expenses are consistently for the same amount (e.g., a salesperson's business dinners always cost $120)

- Reimbursement requests from an employee that consistently fall at or just below the organization's reimbursement limit

- Receipts from a restaurant that are submitted over an extended period of time, yet are consecutively numbered; this tends to indicate that the employee has obtained a stack of blank receipts and is using them to support fictitious expenses

- Receipts or other support that does not look professional or lack information about the vendor, such as phone numbers, physical addresses, or logos

Multiple Reimbursement Schemes

The least common of the expense reimbursement schemes as revealed in the ACFE's research is the multiple reimbursement. This type of fraud involves the submission of a single expense several times to receive multiple reimbursements. The most frequent example of a duplicate reimbursement scheme is the submission of several types of support for the same expense. An example arose in Case 89, in which an employee used, for example, an airline ticket receipt and a travel agency invoice on separate expense reports so that he could be reimbursed twice for the cost of a single flight. The fraudster had his division president authorize one report and the vice president authorize the other so that neither saw both reports. In addition, the perpetrator allowed a time lag of about a month between the filing of the two reports, so that the duplication would be less noticeable.

In cases in which a company does not require original documents as support, some employees even use several copies of the same support document to generate multiple reimbursements.

Rather than file two expense reports, employees may charge an item to the company credit card, save the receipt, and attach it to an expense report as if they paid for the item themselves. The victim company therefore ends up paying twice for the same expense.

Perhaps the most interesting case of duplicated expenses in our studies involved a government official who had responsibilities over two distinct budgets. The perpetrator of Case 83 took business trips and made expense claims to the travel funds of each of his budgets, thereby receiving a double reimbursement. In some cases the culprit charged the expenses to another budget category and still submitted reports through both budgets, generating a triple reimbursement. Eventually this person began to fabricate trips when he was not even leaving town, which led to the detection of his scheme.

Preventing and Detecting Multiple Reimbursement Schemes Organizations should enforce a policy against accepting photocopies as support for business expenses. This practice will help prevent schemes whereby copies of the same receipt are submitted several times. If photocopies are submitted, verify the expense and check it against previous requests before issuing a reimbursement. An organization's accounting system should be set up to flag duplicate payment amounts that are coded as travel and entertainment expense.

It is also important to clearly establish what types of support will be accepted with an expense report. For instance, some fraudsters use a restaurant receipt to claim reimbursement for a business dinner, then use their credit card statement to claim reimbursement for the meal a second time. If the organization accepts only original receipts, this scheme will not succeed.

Expense reports that are approved by supervisors outside the requestor's department should be carefully scrutinized, and in general organizations should require that expense reports be reviewed and approved by a direct supervisor. Employees may take an expense report to a manager from another department because they know that manager will not be familiar enough with their work schedule to spot an inconsistency on the report, or they may try to have two managers approve the same report as part of a multiple reimbursement scheme.

Some employees obtain reimbursement for a business expense, maintain a copy of the receipt, and resubmit the expense after a few weeks. Organizations should establish a policy whereby expenses must be submitted within a certain time frame. Any expenses more than 60 days old, for example, would be denied.

CASE STUDY: THE EXTRAVAGANT SALESMAN2

Dan Greenfield is a CFE who has been investigating fraud for over 15 years, and in that time he's developed a feel for when somebody is being dishonest with him. It's not always the same thing: some people are too defensive, some too nervous, some too angry. And then there are people like Cy Chesterly, who are just too helpful. The first time Dan Greenfield met Cy Chesterly, he quickly got the feeling that Chesterly was trying to put something over on him: “He was just way too friendly, shaking hands, slapping my back. His whole approach was very slick. I definitely got the feeling he was trying to ‘sell’ me.”

And selling is what Cy Chesterly did best. Chesterly was the vice president in charge of sales for Stemson, Inc., one of the largest machine parts manufacturers in the upper Midwest. Greenfield, who specializes in internal investigations, had been called in by the company's new president to look into some disturbing numbers in the company's travel and entertainment expenses. The initial clues pointed to Chesterly as the most likely perpetrator. “You never go into a case trying to pin a fraud on somebody, but you usually start out with a theory of the most reasonable explanation for the losses,” says Greenfield. And in this case, the evidence Greenfield had already, pointed to Chesterly. “Then when you meet the guy and he's way too eager, much more than a normal person would be, that is a clue that you're on the right track.”

Chesterly had been with Stemson, Inc., for over ten years, and in that time he'd helped build it into one of the most successful companies in its sector. Chesterly had the gift of the salesman; he could glad-hand and schmooze with the best of them. He had a familiar good ol' boy charm (he was originally from Texas) that drew people in. He knew every customer by name, and he knew their family members' names, too. Everyone he did business with was “Hoss” or “Buddy,” or “Sweetie” if she was a woman. It may not have been politically correct, but it won him customers, and it built Stemson, Inc.'s business. The company's founder, Charlie Stemson, considered Chesterly his top employee; he even promoted him from sales manager to vice president. Chesterly was the face of the company to all its biggest clients. He was a star.

The biggest weapon in Chesterly's sales arsenal was the company expense account. He wined and dined customers and prospects: steak dinners, golf outings, bars, strip clubs, fishing trips, expensive birthday presents, gifts for their kids, anything it took to ingratiate himself. “He built relationships with his customers, which is what a good salesman does,” says Greenfield. “And he was a heck of a salesman. These people loved him. We interviewed a few customers in the course of the investigation, and they all said what a great guy he was. You send somebody's kid a birthday present, they're going to respond to that. It was a great touch.”

Charlie Stemson, the company owner, knew that Chesterly was running up big expenses with his customers, and he encouraged it. The returns more than justified the investment. Chesterly kept bringing in more and more business, and over time everybody just kind of stopped paying attention to his expense account. “There were no controls on his expenses whatsoever, as far as we could tell,” says Greenfield.

All of that might have gone on indefinitely, if not for a bad turn of luck: Charlie Stemson had a heart attack. He survived, but after that Stemson began looking to retire and bring someone else in to run the business. When Stemson finally found a replacement, his choice was a little shocking. Into this informally run machine parts manufacturing company stepped the new president, Stuart Rusk.

Rusk was a CPA and an MBA, a man who had worked for years in upper management for a major Midwestern wholesaler. He was straight business school, button-down shirt, blue blazer, the works. He was the last person on earth who would seem to fit in at Stemson, Inc., where men like Cy Chesterly and Charlie Stemson wore jeans to work and didn't even have college degrees.

“What happened is, the company had outgrown itself,” says Greenfield. “They started as a sort of mom and pop operation; they didn't have any formal business plan or structure, no controls, nothing like that. When they got big, that system didn't work for the business anymore.” Stemson may have been retiring, but he wanted to make sure his company continued to grow. “He decided that they were going to have to start acting like a big-time business if they wanted to keep growing,” Greenfield says. “That's why he brought in Rusk.” As Charlie Stemson said, they already knew the manufacturing end of the business. They needed somebody who knew the business end of the business.

Rusk did not personally know Stemson, but he knew a friend of Stemson's, and that friend provided the connection. They met for an interview at which Rusk gave Stemson a detailed plan for the company's future; how to maximize profits, reach new markets, cut costs, the works. Stemson was sold. Within a few weeks Rusk took over Stemson, Inc.

“One of the first things he did was look at the books,” says Greenfield, “and when he did, the travel and entertainment expense just jumped off the page at him. It was ridiculous.” Chesterly had apparently started using his expense account for more than just entertaining customers. Entertainment expenses had been rising much faster than sales, and they were way higher than anyone could think was reasonable. Just looking at a few of the most recent company credit card statements, Rusk immediately knew he had a problem. “There was lawn furniture on one statement. Another one had a Ping Pong table,” says Greenfield. “He didn't even try to hide it. He just charged the stuff to the company credit card. Nobody ever looked at it. They just sent in the check.”

Rusk immediately decided to call in a fraud expert to sort everything out. That's where Greenfield entered the picture. His firm was brought in to determine how big a problem there was, and who was behind it. “Of course, everything immediately pointed to Chesterly,” says Greenfield. “He was the guy making most of the sales trips, dealing with most of the customers. Plus you had the charges they'd already found on the credit card.”

But proving what was going on turned out to be some-what difficult. “There was no support of any kind on any of Chesterly's expense reports,” says Greenfield. “We went back four or five years and probably didn't find ten receipts. The items on the credit cards you could track down, but he had trips, meals, car rentals, you name it, that he'd supposedly paid for in cash or charged to his own credit card. He got reimbursed for all of it.” Some of the items on Chesterly's expense reports weren't even what he said they were. For instance, on one report he claimed $600 for an airline ticket, paid for by check; it turned out to be a motorcycle he'd bought for his son.

Gradually, Greenfield and his associates began to sort through all the financial mess. When they did, the information was shocking. “He'd been abusing the system at just an amazing rate,” says Greenfield. “Over the preceding four years, we found about $50,000 in expenses that were definitely fraudulent, and probably twice that much in stuff we suspected but couldn't prove.” Chesterly was using the company's money to bolster his lifestyle. “Vacations, restaurants, furniture, jewelry for his wife, you name it,” says Greenfield. They even found that he had charged professional escort services to the company credit card. “We don't know if that was for him or for his customers. We don't really want to know. It's fraud either way.”

The investigation of Chesterly's expense account abuse eventually turned up other frauds as well. He was cutting special deals to his customers and getting kickbacks in return. “He had an enormous amount of latitude to negotiate prices, expend funds, whatever,” says Greenfield. “There was very little oversight. He took advantage of it.”

Eventually, Greenfield and an associate interviewed Chesterly about the fraud. By that time, they had enough documentation to prove he'd done it. But he never confessed. “He came into the room, told us what a good job we were doing, called me ‘Hoss,’ the whole bit,” says Greenfield. “He kept going on about how much he wanted to help us. But he never said a thing. We caught him lying, we caught him contradicting himself, we showed him proof on some of the frauds. Most people, if you do that they'll confess because they know they're caught.” But not Chesterly. “It didn't even faze him. He was probably the slipperiest guy I've ever interviewed. He'd just keep lying, even when it didn't make sense.” Of course, the fact that Chesterly never confessed didn't mean that the interview was wasted. “When you get somebody who absolutely won't confess, you can at least still document that they're being contradictory,” says Greenfield. “You document the lies and then later you use that in your case.”

In the end, Greenfield documented over $200,000 in losses caused by Chesterly, “and that was just when we stopped counting. I'm sure there was more. But at that point we had enough to go to management.” Chesterly was fired but the company never prosecuted. Greenfield thinks the reason is because of the change in management and the fact that some of the company's customers might have been involved in Chesterly's schemes. “They had an unstable situation at the time and I think they just didn't want to rock the boat any further. Obviously, I don't think it was the right decision. But those things are the client's call; all we can do is give them the information.”

PROACTIVE COMPUTER AUDIT TESTS FOR DETECTING EXPENSE REIMBURSEMENT SCHEMES1

SUMMARY

Expense reimbursement schemes occur when employees make false claims for reimbursement of fictitious or inflated business expenses. There are four principal methods by which fraudsters attempt to generate fraudulent reimbursements from their employers. The first is to mischaracterize personal expenses—such as airfare or hotel costs—as business-related expenses. The second method is to overstate the cost of actual business expenses by altering receipts or by purchasing more than is necessary for business purposes. Employees can also seek reimbursement for fictitious expenses that were never incurred. Finally, employees may attempt to obtain multiple reimbursements for the same expense.

ESSENTIAL TERMS

Mischaracterized expense scheme An attempt to obtain reimbursement for personal expenses by claiming that they are business-related expenses.

Overstated expense reimbursements Schemes in which business-related expenses are inflated on an expense report so that the perpetrator is reimbursed for an amount greater than the actual expense.

Overpurchasing A method of overstating business expenses whereby a fraudster buys two or more business expense items (such as airline tickets) at different prices. The perpetrator returns the more expensive item for a refund, but claims reimbursement for that same item. As a result, he is reimbursed for more than his actual expenses.

Fictitious expense reimbursement schemes A scheme in which an employee seeks reimbursement for wholly nonexistent items or expenses.

Multiple reimbursement schemes A scheme in which an employee seeks to obtain reimbursement more than once for a single business-related expense.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

7-1 (Learning objective 7-1) Explain what constitutes expense reimbursement fraud, and list the four categories of expense reimbursement schemes.

7-2 (Learning objective 7-3) Alpha is a salesperson for ABC Company. In July, Alpha flies to Miami for two weeks of vacation. Instead of buying a coach class ticket, he flies business class, which is more expensive. A few weeks later, Alpha prepares an expense report and includes the Miami flight on it. He lists the reason for the flight as “customer development.” What category of expense reimbursement fraud has Alpha committed?

7-3 (Learning objective 7-4) Why is it important to require original receipts as support for expenses listed on a travel and entertainment expense report?

7-4 (Learning objective 7-5) What is meant by the term over-purchasing?

7-5 (Learning objective 7-7) Provide two examples of how an employee can commit a fictitious expense reimbursement scheme.

7-6 (Learning objective 7-9) How is a multiple reimbursement scheme committed?

7-7 (Learning objective 7-11) Beta is an auditor for ABC Company. He runs a report that extracts payments to employees for business expenses incurred on dates that do not coincide with scheduled business trips or that were incurred while the employee was on leave time. What category or categories of expense reimbursement scheme would this report most likely identify?

DISCUSSION ISSUES

7-1 (Learning objective 7-4) What internal controls can be put into place to prevent an employee from committing a mischaracterized expense scheme?

7-2 (Learning objectives 7-4, 7-6, and 7-8) In the case study “Frequent Flier's Fraud Crashes,” what internal controls could have detected the fraud earlier?

7-3 (Learning objectives 7-4, 7-6, 7-8, and 7-10) Discuss how establishing travel and entertainment budgets can help an organization detect expense reimbursement fraud.

7-4 (Learning objectives 7-5 and 7-6) ABC Company has three in-house salespeople (Red, White, and Blue) who all make frequent trips to Santa Fe, New Mexico, where one of the company's largest customers is based. A manager at ABC has noticed that the average airfare expense claimed by Red for these trips is $755 round trip. The average airfare expense claimed by White is $778. The average airfare expense claimed by Blue is $1,159. What type of expense reimbursement fraud might this indicate, and what controls would you recommend to the company to prevent this kind of scheme?

7-5 (Learning objectives 7-7 and 7-8) Baker is an auditor for ABC Company. He is reviewing the expense reports that Green, a salesperson, has submitted over the last twelve months. Baker notices that Green's expenses for “customer development dinners” consistently range between $160 and $170, and the amounts are almost always a round number. ABC Company has a policy that limits reimbursement for business dinners to $175 unless otherwise authorized. In addition, most of the expense reports show that Green paid for the meals in cash, even though he has been issued a company credit card that he usually uses for other travel and entertainment expenses. What kind of expense reimbursement scheme is Green most likely perpetrating, based on these circumstances?

7-6 (Learning objective 7-10) What internal controls would help prevent an employee from claiming an expense more than once?