5

Research, Monitoring, and Evaluation: What Gets Measured, Gets Done

Creating a Culture of Data Collection and Use

This was the day that we knew we had turned the corner. It was not different from many other days of site visits: the long car ride; the courtesy visit with the head teacher; observations in the grade 1 and 2 classrooms and school library; discussions with teachers, parents, and students about working with Room to Read. But there was also something special about the day. The schools we visited near Ajmer, Rajasthan, in rural India had a different feel about them.

On arrival in each school, Room to Read’s local team rattled off very specific statistics about the schools that we would be observing. Discussions with school staff were more focused than usual. The head teachers had a sharp grasp of daily attendance and the progress in the children’s reading. On the walls, interspersed with children’s artwork and the colorful posters that you often see in classrooms were big sheets of paper that tracked the reading curriculum and children’s reading scores. Writing and words were everywhere, and storybooks strewn around classrooms indicated that they were well used and that a culture of reading was well established.

Teachers had hand selected a girl and boy from each class to serve as library captains. These children were responsible for helping other children check out books and return them to the library on time. Book checkout registries in school libraries were detailed, well organized, and complete. Librarians had diligently recorded the large number of books that had been checked out and returned every day. Parent committees wanted to talk about reading outcomes, what they had seen since Room to Read had started working in their schools, and their expectations for their children’s educational success. Throughout the school visit there was a high sense of productivity and accountability.

At one school, our visit overlapped with a group of Room to Read “enumerators.” These are professionals whom Room to Read hires on a contract basis to collect our monitoring and evaluation data. On this day, the enumerators were collecting information about children’s reading skills in grades 1 and 2. These are data that we collect on a periodic basis to chart children’s progress. We collect information about children’s ability to identify letters in their alphabets, read real words, read nonwords (to see if children can decode letters joined together instead of simply memorizing words), combine words into sentences, and understand what they are reading. We then compare the reading scores of children whose teachers participate in Room to Read instructional activities with children whose teachers do not.

We spent a lot of time with the enumerators that day, as there had been concerns in the past about potential bias in the data collection. There was suspicion internally that past scores were overly positive. Were enumerators conducting the assessment activities in a consistent, fair way? Were all children in grades 1 and 2 equally likely to be selected for the study, or were language-minority students and children with disabilities being excluded? Had schools instructed some children to stay home the day of data collection because they knew they would be less successful?

It was inspiring to see how rigorously the Room to Read staff had designed the study procedures. They had written very specific rules for every step in the process. For example, there were procedures to ensure that all children in grades 1 and 2 had an equal chance of being selected for the assessment. And if a selected child was absent that day, the enumerators would return to the school to conduct the assessment when the child was available. In addition, the assessment conditions were designed to give all children the best chances for success. The space for conducting the assessment was empty and as quiet as the external circumstances would allow.

Enumerators were trained to make the children as comfortable as possible—reminding them that the assessment would be kept confidential and have no effect on their grades at school—and the enumerators implemented the assessment procedures in the same way each time. The process also included both timed and untimed reading assessments. This was to ensure that we had a good measure of reading fluency but also maximized children’s opportunities to comprehend the reading passages without the pressure of being timed. It was clear by the time we had completed school visits that day that our staff and school partners were truly using data to improve teaching practices and children’s reading success.

That the Room to Read country office, school staff, and parents had begun to collect, track, and communicate about data as a normal course of the work was a big deal. It was evidence of a deep “culture of data collection” that we had been trying to achieve for years. In this ideal world, data collection is not seen as an afterthought or a way to police our school-based teams. Whether the results are positive or negative, there is always much to learn from it to improve programs and their replication. Evidence is not something to hide but to shout from the rooftops and share broadly with internal and external stakeholders.

The India country team had been laying the groundwork for one of the key tenets of Room to Read’s success: Investors tend to be more trusting in an organization if the organization is transparent about what is working and not working, especially if investors perceive that the organization learns from its failures as well as its successes. Too many organizations neglect project monitoring or seek to sweep bad results under the rug. This is not only dishonest but also creates superficial communications with stakeholders that can make even the most ardent supporters cynical. We have tried at Room to Read instead to engage investors transparently about ongoing challenges, explaining that if problems such as quality education in low-income countries were easy to solve, they would have been solved by now.

The attitude in the schools was a big turnaround from previous years. In the past, the country office was more reticent about collecting and sharing its monitoring data. In the Room to Read family of countries, India had always struggled to achieve expected project outcomes—and with good reason. As the second most populous country in the world, India has tremendous challenges in poverty and poverty alleviation. Any problem can be an order of magnitude more difficult in India than anywhere else on the planet. In many rural communities, children’s schooling is often a lower priority than other basic needs, and trust in government schools is low. Independent reading is often not even taught in grades 1 and 2, when children are thought to be too young. Under these circumstances, it is also difficult to hire school-level staff members who have the skills to implement effective reading programs.

These are some of the reasons that the India team patiently explained each year why it was not achieving expected program goals. The country team asked the global office to consider lower expectations for our work there. However, we believed that all children deserve the highest-quality support and that expectations should not be set lower just because of contextual challenges. To the country team’s frustration, planning discussions each year started with the question of how to improve the persistently low outcomes.

The statistical tables, which compared the India results to itself over time as well as to the results of other Room to Read countries, challenged everyone to think about ways to make our work more impactful. Perhaps we could reduce our geographical footprint and focus our work in a smaller number of states (which we did!). Perhaps we needed to think about different professional profiles for the school-level staff whom we were recruiting (which we did!). Perhaps we needed to think about aligning our program approach in India more closely to the worldwide approach, which was starting to show some very promising results (check!). Perhaps, too, we needed to rethink our approach to project monitoring so that it became a tool for learning and improvement instead of a way to call out bad performers (oh yeah!).

We used data as the fulcrum for communication, reflection, and change that allowed us to have frank discussions, transform a somewhat vicious cycle of negativity to a virtuous cycle, and help the talented India country office become one of the highest-performing countries in the Room to Read portfolio. In 2015, for example, grade 2 students in India’s project schools were reading an average of 52 words per minute compared to 18 words per minute in comparison schools that did not have the Room to Read program. Knowing from the scientific literature and our own research that children need to be reading at least 40–60 words per minute to achieve modest comprehension, this is a hopeful result to achieve in just a few years at this scale of work. It was the highest average reading fluency score among Room to Read countries at the time as well as the largest difference between intervention and control schools. Again, a strong data system and commitment to transparency gave us the opportunity to promote success and a positive culture of data collection and use at the very end of what we describe in the next chapter as the “implementation chain.”

Incentives and Disincentives for Creating a Culture of Data Collection and Learning

Although data transparency seems obvious—even when results are less than ideal—our long-standing experience is that it is not the norm in the nonprofit sector. Nonprofits do not have the same bottom line of profit as is the case in the private sector, so nonprofit organizations have a lot more discretion to determine and track their own metrics of success. Given competition among organizations for limited financial resources, the desire to put an organization’s best foot forward by emphasizing positive results can be quite appealing.

Our long-standing experience is that the impetus to highlight positive results and downplay “bad” results is particularly strong in the government contracting sector. Large-scale projects funded by bilateral or multilateral organizations such as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the British Department for International Development (DfID), or United Nations agencies that are usually three to five years in duration are just too short to achieve the transformational goals that they seek to accomplish. Therefore, historically, the bilateral agency overseeing the project sets a relatively low bar for achieving results so that the project can be deemed successful, thereby justifying future requests from its own government funding source. This is perhaps an oversimplified view of the world, but we would argue that the incentives for robust project monitoring in bilaterally funded projects are not always strong. Financial costs are high, the challenges of collecting data in difficult country contexts are great, and the risks of failing to achieve project goals can be substantial for bilateral funders, host-country governments, and implementing partners.

More recently, though, we have seen the reverse situation. Substantial pressure has grown in the international education community, including the U.S. government, to help 100 million young children to become independent readers. This is a goal that USAID included in its 2011–2015 education strategy and one that other bilateral and multilateral organizations have taken on in recent years as their big challenge in international education. In setting this larger sector goal, we have begun to see huge expectations for children’s achievement in recent USAID requests for proposals.

In a large-scale USAID reading project that we are helping to implement right now in Rwanda, for example, the expectation is that 65% of the more than one million children in grades 1–3 in the country will be reading fluently and with comprehension by the end of the five-year project period. Children must achieve a minimum of an 80% score on reading comprehension questions. This level of comprehension is a goal that no reading project has achieved at such a scale. Particularly daunting is the fact that a 2014 reading study in Rwanda found that 60% of grade 1 students, 33% of grade 2 students, and 21% of grade 3 students could not read even one word of grade-level reading passages.1

As the project partner responsible for ensuring children’s reading success, Room to Read has a monumental challenge to help increase children’s reading success across the country. We have never achieved such a goal but are working hard to rise to the challenge. This will be a true test of whether we can support children’s reading development at such a large scale.

However, it is yet to be seen whether the value of learning and being open about problems will trump the need to show results. Funding agencies and their governments’ budget appropriations bodies must set the tone.

Research, Monitoring, and Evaluation at Room to Read

We organize our work at Room to Read such that research, monitoring, and evaluation (RM&E) is integrated into everything that we do. This starts with a global RM&E team that is dispersed around the world: in the United States, Southeast Asia, South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa. These people are responsible for setting the overall agenda for the organization as well as supporting country teams in their RM&E activities. Most country offices then have at least two related staff. These staff members are responsible for implementing annual worldwide monitoring activities, cross-national evaluations, and country-specific research. We conduct separate research, monitoring, and evaluation activities that feed into reflective discussions about program improvement and implementation effectiveness as well as much of our internal and external communications.

We built this full RM&E global structure eight years into the organization’s history. This staffing represents a major investment of organizational time and resources, but it is one that we think is essential for the long-term success of the quality of our programs.

Monitoring

The worldwide monitoring process is a cross-nationally consistent approach to collecting similar data in every program country and charting progress over time. It helps us to track the extent to which we are implementing the number of projects that we have planned as well as the extent to which those projects are achieving their expected goals.

This means not only following the number of girls who are participating in our Girls’ Education Program but also whether those girls are staying in school and participating in life-skills activities. It means we monitor not only the number of libraries that we have established but also how many books children are checking out from libraries. And we don’t just count the number of teachers we’ve trained but also whether their children are becoming effective, independent readers.

Every year, we review the worldwide indicators, modify the forms and guidance, and monitor more than 4,000 project sites. We then input the information into an enterprise database management system that we customized off the Salesforce.org platform, and produce internal and external reports. The external report, which summarizes trend information, is published on Room to Read’s website, while the internal report details country-specific information and cross-country comparisons. This information is used to identify successes and challenges, promote discussions within country teams as well as between country teams and the global office, and feed into annual country reviews and planning.

We have also started to collect what we call “program implementation monitoring” (PIM) data on a consistent basis. This allows us to determine whether schools are implementing projects as intended. PIM is early in implementation but is designed to answer key questions such as how long it takes for a school library to be set up and become fully functional, and how long it takes for a teacher to become proficient in reading instruction. With clear expectations for what we are trying to accomplish for each of our program areas, program implementation data also help us to determine which projects need additional help and which are doing fine without regular monitoring and coaching visits.

These data also help us to understand when we are implementing activities as intended but still not achieving our expected results. So, this information provides vital signals about when we need to review our overall program designs.

One of the biggest challenges in program monitoring is establishing appropriately collaborative relationships among program, implementation, and monitoring staff. Inevitably, staff members who are responsible for program design and implementation have some discomfort with project monitoring. After all, monitoring is a review of their work. It does not matter how often we talk about ourselves as a learning organization, or how much we say that we value transparent and open reflection—monitoring is equated with judgment, and judgment produces anxiety. Anxiety is then magnified if monitoring activities begin to feel like policing, and results of monitoring activities have consequences for people’s job status, career progression, and compensation. We have experienced high tensions in some countries historically related to monitoring—particularly when program and implementation staff don’t believe that the monitoring staff understand what they do or monitor their programs effectively.

For these reasons, establishing positive working relationships early in the process of designing program and monitoring activities is critical. Research, monitoring, and evaluation staff need to be full partners in program design to ensure that monitoring systems align with programs. If they do not align or are thought not to align, including a clear understanding of how results will be used to improve work and help children, monitoring efforts are doomed to fail. Efforts lose credibility and are not taken seriously when results are published.

It is also important that there be clear rules for engagement when implementation and monitoring staff are working in schools at the same time. Monitoring staff should not be intrusive and overbearing when they are in schools. They should not be perceived as controlling or patrolling the work of project implementers or school staff. The more unobtrusive they can be to blend quietly into the back of classes or conduct their assessment activities in a separate space, the better.

At the same time, it is equally important that there be at least some separation between implementation and monitoring activities. At Room to Read, school-level staff are often responsible for collecting some monitoring data. In fact, we have developed rubrics of data collection that implementers are supposed to use during each school visit. Some of this information just feeds back to their supervisors for immediate action, as necessary, while other information feeds into worldwide program monitoring systems.

However, there are times when we collect student assessment data in which we need to make sure that the people who are responsible for implementing activities are different from the people who are collecting the assessment data. Sometimes, the outcome we are monitoring even requires that we hire external data collectors to maintain real or perceived integrity in the process. Otherwise, there can be a concern about bias or conflict of interest.

The separation between monitoring and implementation also extends to reporting. Report writers need to maintain a clear distinction between analysis and advocacy. Analytical writing requires more of a neutral and fact-based approach (“Just the facts, ma’am”), whereas persuasive writing champions the results (“Our work is the best thing since sliced bread”). Both kinds of writing are important for an organization such as Room to Read.

One just needs to be clear, though, who is writing the reports and for what kind of a purpose. Regular monitoring reports should skew heavily on the side of analytical writing. Room to Read’s annual internal Global Results and Impact Report, for example, focuses exclusively on results and country office reflections on the reasons their results in any year are relatively strong or weak, as in: “Country X exceeded its past success by 0.3 standard deviations this year. It tightened its monitoring visits and focused much more on helping teachers with instructional routines than it had done previously.” This is substantially different from a blog that we might post with the headline, “Room to Read programming in Country X beat its previous outcomes for the third year in a row.”

Evaluation

Evaluations are structured research activities that examine the extent to which program activities lead to expected outcomes. We try to understand why what we do makes a difference, and what we might think about doing differently to achieve better results. Unlike monitoring activities, which we consider integral to our regular project implementation, evaluations are special activities that are funded separately from our ongoing program implementation expenditures. A simple analogy to explain the difference between monitoring and evaluating activities is to compare cooking soup with eating it. Monitoring is like the chef tasting the soup along the way to adjust ingredients for best results. Evaluations are like presenting the soup to the diner and asking for feedback on the finished product.

We conduct some evaluations ourselves while we contract others externally. Evaluations usually require detailed planning, the hiring of temporary data collectors (“enumerators”), and consideration of comparisons. In some instances, we compare results in the same schools over time. In other cases, we compare results to control schools that are like the schools in which we are working but have not received Room to Read support. In all instances, we do our best to maintain the highest level of rigor in evaluation procedures while recognizing the challenges of working in difficult country contexts where schools can be shut down because of heavy rains or political instability, or where government permissions can be rescinded just before data collection takes place.

Room to Read also follows high ethical standards in the protection of personal data. We use international standards to make sure that we have people’s permission to participate in research and evaluation, are clear with participants about the purpose of the study, and keep information about program participants confidential. Although educational research in general does not carry the same potential risks as drug-intervention studies, or studies about voting behavior in politically repressive countries, results can have implications for people’s jobs or well-being. We are even more careful in research and evaluation involving our Girls’ Education Program, in which our life-skills education and mentoring activities often do push the boundaries of cultural norms and can have implications for girls’ standing with their communities.

Research

Research is the last component of Room to Read’s “Research, Monitoring, and Evaluation” system. It includes the studies that are meant to inform our programming other than direct evaluation of our program models or implementation. Studies can be simple and short in duration or complex and extend one or more years. They can be initiated through the global office or any country office. In addition to larger research projects, one of the most exciting parts of our research program is country-initiated research. These are research questions that countries identify as important for their program improvement.

For example, why are dropout rates among girls higher in one country than in other countries? How does the creation of classroom libraries change implementation as compared to separate libraries? What is the relative value of hiring local organizations to serve as school-level support staff instead of hiring social mobilizers, library management facilitators, or literacy coaches directly?

Country and global office team members then work closely with each other to develop the research methods to answer the question, the research project is reviewed by the global RM&E director, and the project is launched collaboratively between the country and global office. Data are analyzed, results are written up, and reports are shared among all countries offices and the global office so that we can learn from countries’ experiences.

Room to Read has been working on building the capacity of country offices to perform effective local research for many years. We tend to hire outstanding local research officers with strong academic credentials, but it is often difficult to translate academic experience into equally strong study designs and implementation capabilities. Some of the biggest challenges are in crafting focused research questions, linking research questions to appropriate study methods, summarizing study results, and facilitating discussions about how to use evaluations and research results to improve programs.

Every year, when the global office solicits research ideas from country offices, we receive long, enthusiastic lists of ideas. In almost every instance, topics are interesting and merit research. Questions such as “What are the major causes of poverty in a particular geographic area?” can be an important starting point for many new public and private initiatives.

However, the real question that we have to ask ourselves is “Assuming we find something interesting in research results, can Room to Read do something meaningful with the information?” This is the “So, what?” question. In the case of the “What causes poverty?” question, Room to Read has made the conscious decision not to pursue this kind of research. Instead, we maintain focus on our programming and do not try to tackle other important problems such as the broader reasons for poverty that communities might face. Of course, one can always learn something from high-level research questions that can improve program activities. The issue is whether we can learn something important enough to be worth the investment for us. Studies take time, money, and effort, and we need to be as strategic as possible in the use of these resources.

A second common problem with country-initiated research topics is that they are often redundant, covering questions that have already been answered elsewhere. Take, for example, the issue of girls’ dropout rates from school. In most countries in which Room to Read works, extensive research on girls’ dropout rates has been done. Do we then have good reason to believe that the causes of dropout in a region are so different from other parts of the country that they warrant special study? Perhaps. In Nepal, for example, the Kamlari system of indentured servitude in the low-lying regions is a unique historical phenomenon that is relatively limited to that part of the country. In most instances, though, differences across a country may not be as extreme, and new research might therefore not be warranted.

Before launching a new research study, we ask ourselves questions such as “Have we done a literature review to see whether a study has even been done on the area itself? Has Room to Read already conducted a similar study in a country nearby that could help us understand the issue in the first country well enough?” It is surprising how often we forget to examine whether a research question has already been answered well enough elsewhere.

Third, even after we have identified a meaningful research question, the proposed research methods must be effective and efficient. Take again the question of why girls drop out of schools. This really was a key research question in one country in which Room to Read was working. We did not feel as though we had enough information to understand unusually high dropout rates. However, the country team proposed a 20-page survey that was supposed to be used with scores of intervention and control schools. This design was completely out of scope with the basic question we were asking. Instead, what we really needed to do was interview a sample of girls who had left school early to find out about their experiences. These conversations would have given us much more information than an expensive, complicated survey design.

Finally, when conducting research or evaluation activities in complicated situations, it is important to anticipate and preempt problems with data collection to the extent possible. We have implemented some studies over time, for example, in which schools initially selected as “controls” later started to receive program support without the knowledge of the researchers. This was a big disconnect. The programs team was not in close enough conversation with the research team, and this simple act devastated our ability to study the benefits of our program over time.

For all these reasons, research and evaluation designs should be developed carefully, in consultation with program design and implementation staff, and checklists of problems to be avoided should be considered with any new study opportunity.

RM&E at Different Phases of Organizational Development

Although monitoring, feedback, and transparent reporting has been a fundamental part of Room to Read’s culture from its inception, the way in which we approach this part of our work has changed markedly over time. Like many young organizations, it was important to us even in our very early days to document the number of books that we distributed, libraries that we established, and girls whom we supported with tuition scholarships. Now, 18 years later, we can still go back to those initial data and chart the number of projects that we have implemented since inception. We also know among those first scholarship recipients how many of those girls completed high school. However, it is also the case that in those early days we did not have many staff members, nor did we have a deep program outcome focus. Although we cared about quality programming, the immediate concern was in getting projects in place so that we could serve as many communities as possible, not launching a comprehensive monitoring system.

Perhaps the first major organizational shift in RM&E, from start-up to transition, came in 2004, when board members and management began to think about monitoring and evaluating the literacy and girls’ education programs more formally. With a few years of implementation under our belts, and some momentum building from a growing investor and country base, it was time to think about what was going well and how to improve our work. It was at that time Erin reached out to Cory and Room to Read began to think about its first external evaluation.

Although it might seem like a small issue, the decision to invest in an external evaluation was a big deal. First, it meant diverting hard-earned funds away from direct program implementation and into evaluation work. This is not easy to do when you believe that all children around the world need urgent help and that every day and dollar matters. Second, it was risky to open ourselves up to external scrutiny. What if the evaluation identified major problems? Not only would this be a blow to our organizational morale, but it might also scare investors away.

Nevertheless, we took the plunge and hired our first external evaluators. This turned out to be a great experience. The evaluators were helpful in coaching us through the evaluation process and helped us think about longer-term systems for tracking our results. In addition, we were pleasantly surprised (and relieved) that the overall results were quite positive. Interviews with partners across countries and program areas indicated very strong appreciation for our work. The experience left us much more confident and bullish on M&E. It also left us craving more information. The 2006 evaluation largely focused on people’s views about Room to Read programming. In retrospect, it is not surprising that partners and communities liked our work and believed it was making a difference. After all, who would not like new school libraries, books, or girls’ scholarships?

Nevertheless, some of the feedback in the evaluation and from country teams, as we explained in Chapter 4, indicated that we needed to do a lot more work to ensure that our libraries were being used fully and integrated with school activities. This was the point at which we began to hire school-based field staff and develop more meaningful metrics for monitoring program quality.

The years from 2004 to 2009 were a vibrant transition time for RM&E at Room to Read. We hired a global director and country-based staff to oversee our monitoring and evaluation work in countries. We started to develop a comprehensive, worldwide set of indicators to measure program quality and outputs as well as country-specific indicators of program development and implementation. We completed our first external program evaluation, and we began to develop internal systems for incorporating lessons from the monitoring results into our annual planning.

Cory was not yet a Room to Read staff member at the time but was already a close advisor to the organization. It was Erin’s straightforwardness and passion for transparent, data-anchored decision making that piqued his interest in Room to Read in the first place. He remembers being extremely impressed with the seriousness and thoughtfulness by which Room to Read began to grow its monitoring and evaluation function. The organization was fearless in its early efforts to try new approaches, and to be very up front about what was working and not working. Cory encouraged Room to Read even during this time to share its experiences with monitoring and evaluation as part of a larger discourse about education and international development. He felt that Room to Read was already on the cutting edge in study methodologies, and the field would gain a lot from hearing about its work.

However, this was not an easy sell. The organization was still reticent to share its experience broadly—not because it had anything to hide but because it was shy in feeling that it had not yet perfected its methods. It didn’t believe that it had anything important yet to say. With gentle and persistent prodding, though, Cory was one of the voices that gradually persuaded the team to participate in international forums and workshops. And as staff began to present their findings—as preliminary as the findings were thought to be—other organizations began to take notice. And although Room to Read was not very well known at its first few conferences, its reputation grew rapidly, and it became quickly known for its deep program work and reflection.

The next big milestone in Room to Read’s research, monitoring, and evaluation work—and the start of our transition into maturity in this focus area—came in 2009. Erin, along with the management team, was in the middle of developing the next five-year global strategic plan for Room to Read. We were eager to deepen the quality of our programs so we could have greater impact on the educational outcomes of the children and schools where we were working. Fortunately, we found a great supporter of evidence-based programming in the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. They signed on to fund our global strategic plan development as well as a host of follow-on evaluations and research studies. The Gates Foundation’s generous investment launched a wave of internal research and external evaluation that has had a tremendous impact on our work, our credibility, and our visibility in the international development community, and our contributions to the larger literature. This was the time when we began to invest in country-based research and evaluation activities in addition to our regular monitoring activities.

Program Implementation Monitoring: Identifying Problems and Clues for Resolving Them

Today, research, monitoring, and evaluation continue to be integral parts of Room to Read’s work. Our worldwide monitoring system is stronger than ever, with annual data collection, reporting, and reflection becoming smooth, regular activities deeply embedded in our systems. Each year we review the organizational indicators to determine their importance for our programs, operations, communications, and business development. We then adjust as necessary; update our data collection forms; train country leads, who in turn train enumerators; collect data; enter data into the Salesforce database; prepare preliminary statistical tables; reflect on findings and adjust program design or operations as appropriate; and publish our findings.

This design, implementation, and reflection process is illustrated in Figure 5.1, a workflow diagram developed by the program design team in 2014. This diagram has been a powerful tool for organizing our thinking. We have reproduced it in numerous internal and external documents and presentations, used it to reorganize our staff roles and responsibilities, and resurrected it to remind ourselves periodically about our overall approach to programmatic research and development.

FIGURE 5.1 Room to Read Workflow Diagram.

The diagram shows how program content and related training that starts with the global office (though based deeply on experiences from our country offices) cascades through the system such that our intended approach becomes implemented at the school and classroom level.

Key to this process are the two feedback arrows that flow back into the system. They illustrate two important ideas. First, there is the recurring theme that monitoring feedback has consequences. When something is not going right in our work, we need to take stock and adjust accordingly. Second, the diagram shows that there are different ways that our work can go wrong and that each has a different effect on the workflow process.

For example, sometimes we have problems with fidelity. This means that the program is not being implemented as it was designed. There could be a problem in delivering furniture to school libraries. Or literacy coaches could be unable to visit their schools for three months because of a government strike or bad weather.

In other situations, the problem may not be with the implementation but with the design itself. We could find, for example, that teachers are doing everything that we ask in reading instruction or library activities, but children are still not learning to read or developing the habit of reading. These are situations in which we need to think hard about the overall design. What could be the problem? Perhaps adolescent girls are not achieving more success in school because they have more chores at home and therefore less time to do homework than do boys.

All this is to say that knowing why we are not succeeding in our work is the essential first step in identifying a reasonable solution. How do we do this? As we explained previously, we are in the early stages of implementing a worldwide system called “program implementation monitoring” (PIM). PIM is meant to help us understand the fidelity of program implementation. It includes our library rating tool, which tracks the physical elements of school libraries, library systems, and library activities; our reading instruction observation protocol, which helps us understand the extent to which teachers are implementing instructional routines and taking necessary corrective actions; and, although not an exact parallel, our girls’ education risk-and-response tool.

Each of these tools helps us to track progress in implementing our programs as well as guidance for next steps. The library-rating tool, for example, is a paper-based checklist recording form that library management facilitators use when they visit their schools each month. They track a set of 15 indicators per library. Then, based on the findings, they work with school librarians on prioritizing and completing each element of library programming.

This tracking system is an invaluable tool for planning. It helps us to identify the projects that need additional help as well as the kind of help the projects require. It also helps us to determine when a school library is at the phase of development at which we can stop our support work and shift our school-based staff to another library or other priorities. We have seen incredible transformations in the focus of our field-based staff when this kind of tracking is in place.

We have also discovered that it does no good to use such a tool simply to list all the issues that need to be addressed at a library. When we originally created the tool, library management facilitators would debrief with librarians at the end of each monitoring visit by telling them the entire list of program elements they needed to work on. Without helping schools to prioritize the next steps, however, the overall project becomes overwhelming and progress is stunted. Teachers and librarians do not know where to begin. However, once our global RM&E team began to work with our programs team to prioritize the list of program elements, and our facilitators helped schools to prioritize their own work, the tool became much more useful.

Clarifying the implementation process is the first step. Like the development of any project plan in which activities need to be spaced over time, planners need to think about which activities must be implemented in a specific order. This is what the Project Management Institute calls “mandatory dependencies.”2 School libraries, for example, must have bookshelves before they have books, and the libraries must have books before librarians can start weekly reading activities. However, even in situations in which these dependencies are “discretionary”—meaning that there is no need for a specific order in implementation—it is still good to determine a specific order anyway. This helps the project staff and schools with a clear plan of action. It also focuses people’s time, work, and other resources to be as targeted as possible. As the title of this chapter states, one of our favorite phrases at Room to Read is, “What gets measured, gets done.”

Next Steps

The future is bright for Room to Read’s work in RM&E. As we continue to grow our reputation for transparent monitoring and rigorous evaluation, institutional investors such as corporate and family foundations are increasingly coming to us to consider new research opportunities. They know that we have trusted relationships with governments and communities as well as long-standing programs and RM&E systems in place to test hypotheses about important issues in girls’ education and literacy.

We are also receiving more invitations to participate in international education research and policy forums—not only in the United States but also in the countries in which we work in around the world. Room to Read’s input into these discussions is particularly important as the world community grapples with the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals that we are set to reach by 2030 and establish the kinds of metrics that will authentically track our collective progress.

One of our most exciting continuing RM&E projects continues to be program implementation monitoring. Although this might seem like a humdrum topic, it is one of the key tools enabling our ability to scale effective programming for ourselves as well as our ministry of education partners.

For example, as we wrote in Chapter 4, hiring school-based support staff was one of the most important steps that Room to Read took years ago to promote the quality of our programming. These are the people who monitor girls’ success in school, the functionality of school libraries, and teachers’ progress in reading and writing instruction as well as guide schools toward successful outcomes. At the same time, school-based support is expensive and difficult for Room to Read—much less ministries of education—to sustain in the long run. How can systems incorporate such an expensive yet vital function? PIM helps answer that question.

By understanding how long it takes to prepare a teacher, librarian, or social mobilizer in essential activities, and knowing how much support is necessary to master core skills, Room to Read and our ministry partners can become much more efficient in deploying school-based support staff.

Key Takeaways

- Remember that targeted RM&E is a wise investment. You will always be under pressure to invest scarce financial resources and staff time in program implementation. This, of course, is the reason you have created a social enterprise in the first place. But investing in RM&E, too, can help to ensure that programming is as efficient and effective as possible and that you can communicate effectively about it in the long run. It is difficult to raise funds for RM&E but important to help investors appreciate its value.

- Understand that research, monitoring, and evaluation is critical for the development of any entrepreneurial social enterprise, as it provides input into internal and external communication, improving operations and design, scaling your own organizational goals, and contributing to the larger field.

- Think about RM&E at the earliest stages of organizational start-up. This does not mean having a robust RM&E system from the get-go. However, thinking about RM&E early in an organization’s development helps to focus program design and implementation, prove your theory of change, build an internal culture that values being a learning organization, as well as engage your key internal and external stakeholders in evidence-based programming.

- Embed program monitoring deeply into program implementation activities. Rating systems, observation protocols, and similar tools are essential to understanding whether program activities are being implemented in the way they were intended (program fidelity) and, if so, whether the activities are yielding the intended outcomes and impact.

- Be curious about what the data are telling you. Being a data-driven organization requires developing systems and processes that are actionable. It is important to collect, analyze, and then, most importantly, course-correct as necessary and make decisions based on the evidence.

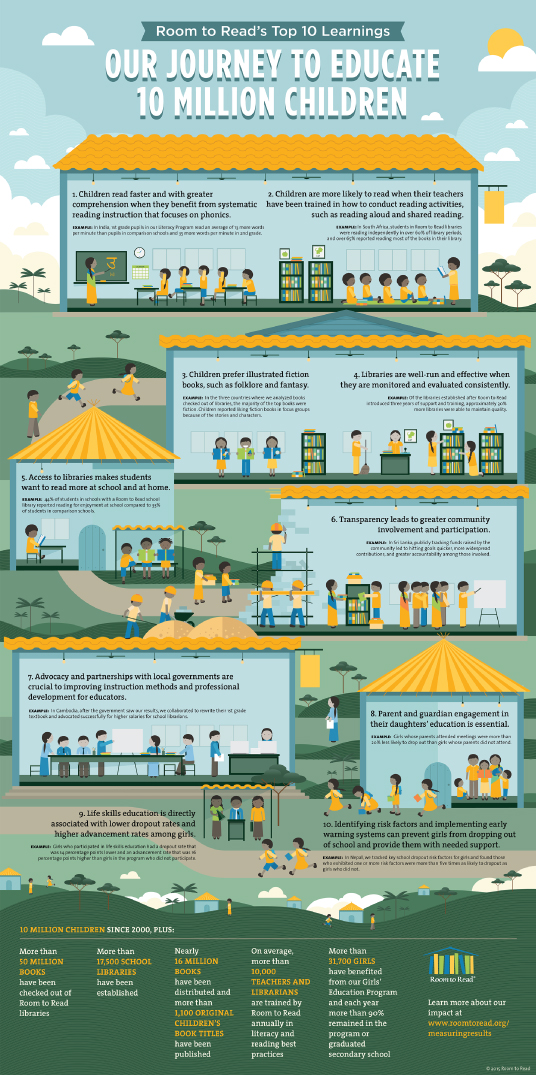

- Use data to help tell the story of impact and help communicate your own learning to key audiences (for example, see Figure 5.2). We are not just data geeks at Room to Read. What we really care about are outcomes for children, schools, and communities. Data lead to insight and knowledge, which leads to action, which leads to better outcomes, which leads to greater scale and points in the direction of system-wide change.

FIGURE 5.2 Infographic Illustrating Lessons Learned from Monitoring and Evaluation. - Know that sometimes data don’t tell a clear or full story. Monitoring and evaluation data are never perfect. The mere creation of information systems can bias what implementers do and do not do. It is therefore important to determine which kinds of data are most important for which purposes. The postmortem discussions among your program and RM&E teams after data are collected and analyzed are therefore key to determining next steps. The experience, wisdom, and better decisions that come out of the team discussions are enlightening and help build capacity to make smarter and smarter decisions with data.

- Always, always, always be honest with yourselves, your investors, and other stakeholders about what is working and what needs to be changed. Acknowledging problems directly and clearly and then developing strategies for fixing them instead of hiding them builds trust, appreciation, and long-term support for your hard work. It is also important to remember that people can be quite sensitive about positive and negative findings. The way that results are communicated can have a big effect on what people do with the information.

- Sing it from the rooftops! Don’t be shy in sharing your RM&E findings with external audiences in blogs, reports, and public forums. Even if you think it may be too early in your organizational evolution to do so, there is a huge demand for information about effective programming at every stage of development. You can increase your visibility and brand, generate revenue, and contribute to the field by sharing your findings and lessons learned whenever possible.