CHAPTER 6

Company Building

The essential thing is action. Action has three stages: the decision born of thought, the order or preparation for execution, and the execution itself. All three stages are governed by the will. The will is rooted in character, and for the man of action character is of more critical importance than intellect. Intellect without will is worthless, will without intellect is dangerous.

— Sun Tzu, as quoted in the Marine Corps Warfighting Doctrine

MARK AND DAVE WERE THE CO-FOUNDERS of BetaSheet, a pharmaceutical drug discovery company. Before starting BetaSheet, Mark had been the VP of Computational Chemistry of a startup acquired by Genentech. At Genentech Mark realized it was possible to revolutionize drug discovery by using computational methods rather than traditional wet labs. He passionately believed scalable drug discovery was going to be the new direction for the pharmaceutical and biotech industries, and he tried to convince the company to fund a new lab inside the company. After Genentech said his idea was not big enough to be of interest to the company, he decided to start a company himself. He took Dave, his Director of Computer Methods Engineering, with him.

After some initial fund-raising, Mark became a first-time CEO, with Dave as his VP of Development. I'd been introduced to Mark by one of his VCs and sat on his board from the beginning. From my front-row seat I watched BetaSheet go through all the startup ups and downs, made even harder by a market glutted with products, a collapsing biotechnology industry, and a complicated internal organization. Not only was BetaSheet trying to develop a complex piece of software to predict which drugs might be active, it was taking its own predictions and attempting to make active drug compounds. The idea was that potential customers would turn from skeptics to believers if BetaSheet walked into a sales presentation with a new, until now unknown, version of one of their commercial drugs.

One of the first crises occurred nine months into the company's existence. For the fourth consecutive month, Product Development seemed to be going nowhere. Mark had already shared his opinion that Dave was not up to running an entire engineering department. After some heart-to-heart conversations with VCs over the next several weeks, Dave agreed to step aside and stay with the company as Chief Technology Officer. While the search went on for a new VP of Engineering, Mark jumped in and took charge. In the eyes of the board, he performed a small miracle by improving morale and getting a working product headed out the door. By the time the new VP came on board, all the hard technical problems had been solved.

Meanwhile, at the prompting of one of the VCs, an experienced VP of Sales from a big company was hired despite Mark's misgivings he didn't “feel right” for a startup. Eleven months later, the VP and the national sales force he had hired were burning money like there was no tomorrow. There was embarrassed silence at the board meeting when the VP said for the sixth month in a row, “We have lots of activity in the pipeline, but it's real tough for a startup to close an order in a major drug company. I don't know when we'll close our first order.” At Mark's urging, the VP was let go. With strong reservations (as Mark had no sales management expertise), the board agreed to have Sales report directly to Mark until a replacement was found.

In the following six months, Mark delighted us by personally selling the product to the first three top pharmaceutical companies he approached and helping the sales team build a solid sales pipeline. Later, we didn't say much when we found out he had promised these early customers the moon, since our competitors were turning into piles of rubble. The company was moving forward, the sales team was pumped, and the new VP of Sales came on board with a running start.

Next to go was Bob, the Chief Scientist and head of the chemistry group. After Mark fired him, Bob unloaded. “Mark has a new idea a day,” he said, “and it's impossible to complete a project before he changes his mind. And when things aren't the way he wants them, he starts screaming at you. He doesn't want any discussion; it's his way or the highway. In the end you are either going to have your entire exec staff quit, or Mark will end up replacing us all with execs who simply do what he says.” Those turned out to be prophetic words.

Despite the bumps in the road, the next few board meetings were pleasant. Sales seemed to be looking better and better. Yet Mark sounded more and more frustrated. Over lunch one day all Mark could talk about was that competitors were going to put the company out of business if we didn't follow up on his new ideas. I asked him if Sales was as worried as he was about competition. His response caught me off guard. “The VP of Sales won't let me talk to our salespeople or customers anymore.” On hearing this I sat up and leaned across the table to hear the rest. “Yeah, our VP of Sales told me we can't start selling products we don't have or we'll never make money.”

The rest of the lunch was a blur. As soon as I got to my car, I called the VP of Sales and got an earful. Mark was trying to convince the sales force what they really ought to be selling was his next great vision. Any time the salespeople tried to take Mark in to help close a customer, he tried to convince them it was the next product, not this one, they would want to buy. This was not good.

There was more. Mark, the Sales VP told me, was driving her crazy, coming in daily with a list of new sales opportunities she should be pursuing and badgering her to use sales presentations full of technical features, not solutions to what the customers had said were their problems. On top of that, she couldn't even use the new BetaSheet company literature to train the 12 salespeople she had hired since Mark had rewritten all the new data sheets to push his new product ideas. She asked whether I knew the new VP of Marketing was spending all his time on PR and trade shows since Mark had taken on product strategy and the new product requirements documents himself. I promised the board would talk to Mark.

The next week, two board members met with Mark about his relationship with Sales. Mark believed BetaSheet needed to keep pushing the edge of innovation, not get used to being settled in. BetaSheet, he complained, was turning into a company of “don't rock the boat” people in suits. He was going to keep rocking the boat because that was his job as CEO. The consensus around the board was that Mark needed to be managed. We agreed to wait and see how the situation at BetaSheet developed.

What we didn't understand was that back in the company life was anything but pleasant, as I was to learn from Sally, the CFO. Sally had been with BetaSheet since the beginning and was a gray-haired veteran of many startups. Her observations were dispassionate yet pointed. She said Mark thrived on chaos and managed well in it. The problem was BetaSheet needed to become a company that moved beyond chaos. It was getting bigger, and since the span of control was beyond Mark's reach, it needed process and procedures. Yet Mark had derisively rejected all of her proposals on how to put processes in place to manage the size the company would become. “We have a dysfunctional company. The exec staff is now split between people who have given up thinking for themselves and just do what Mark tells them to do, and those who still can think for themselves and are going to leave. The company has grown past Mark, and the board needs to make a choice.” I left the restaurant hearing a stark call to action.

Perhaps my admiration for what Mark had accomplished as an entrepreneur blinded me to his limitations, but I thought it was worth a few more lunches to see if I could get him to realize he needed to change. Mark listened and nodded in the right places as I tried to explain that needing a modicum of process and procedures was a sign of success, not failure. I thought I had made some progress until Mark repeated that he was the only one in the company who was trying to see what was coming next in our market and no one in the company wanted to go there.

Over subsequent lunches I broached the subject of a transition. Taking one last shot at helping Mark understand, I observed that fixation on the next-generation products and customers was the role of a Chief Scientist or VP of Product Strategy. Mark should think about whether he truly enjoyed being CEO of a company that had grown beyond being a startup. Perhaps, I suggested, we could hire a COO to help Mark worry about the day-to-day operations. Or perhaps Mark might want to be both chairman and head of product strategy. Or could he think of some other roles that might work? None of these alternatives meant Mark had to give up control—just look at Bill Gates at Microsoft or Larry Ellison at Oracle. They each had people around them to manage the things they weren't great at. Mark promised to consider a transition, but judging from what happened next, he must have dismissed the idea as soon as he left the restaurant.

Things finally came to a head when the entire BetaSheet exec staff went to the office of the lead VC and said they were resigning en masse unless Mark was removed. Not surprisingly, the VCs concluded it was time for a new CEO.

The next board meeting was as difficult as I feared it would be. Mark complained bitterly, “How come none of you ever told me we were going to hire a new CEO?” I winced as Mark's lead VC recounted how Mark had said from day one he understood the company would someday hire a CEO. “You always said you'd do what's right for the company. I can't believe you're acting like you never heard this before.”

I listened as Mark vented. “Telling me that needing to hire professional management is good news for the company is just a crock. After three years of working 80-hour weeks and doing such a great job building my company, the board is going to take it all away from me! I haven't done anything wrong and the company is running just fine. Making me Chairman is just a polite way of getting rid of me. You don't realize how badly someone from the outside will screw up our business. No one could possibly ever know our company as well as I do.”

The result happened as if it was preordained. I won't forget the conversation I had with Mark after the meeting. “Steve, how did it ever come to this? Should I fight my dismissal? Do I have enough shares to throw my board members out? Will you help me get rid of them? What if I quit and took all the key scientists and engineers? They'd follow me, wouldn't they? Those damn VCs are stealing my company, and they're going to screw it up and ruin everything.”

The names have been changed to protect the innocent, but I have sat through too many painful board meetings like this. In the world of startups, some form of this meeting is probably occurring every day.

At first blush the questions this story, and the countless others like it, raises are these: Was Mark being unfairly jettisoned from the company he built? Or were the VCs doing what they were supposed to do to build value in the company? The answers are almost a litmus test of the beliefs you bring to reading this book. However, there is another, deeper set of questions. Could Mark have grown into a better CEO with more coaching? Did I let him down? What type of CEO should the company hire? What should Mark's role be? Would BetaSheet be better off without Mark in six months? In a year? In two years? Why? After you're done with this chapter, I think you'll understand why both Mark and his board could be right and dead wrong.

The Company-Building Philosophy

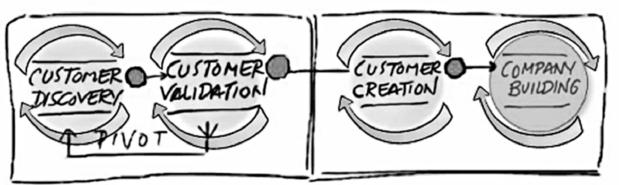

The first three steps in this book focused on developing and understanding customers, validating sales with earlyvangelists, and creating a market and demand for the product. The next challenge, and the final step in the Customer Development model, is to build the company.

One of the mysteries about startups is this: Why does staffing heavily early on in some companies generate momentum and success while in others it leads to chaos, layoffs, and a death spiral? Why do some companies catch fire and others enter the land of the living dead or run out of money? When do you crank up the burn rate and hire, and when should you cut spending and go into survival mode?

Another of the puzzles of entrepreneurship is why some of the largest and most successful companies are still run by their founders long after they have become established. Ford, Microsoft, Nike, Polaroid, Oracle, Amazon, and Apple all belie the conventional investor wisdom that entrepreneurs eventually are outgrown by the companies they create. In fact, these companies prove a very different point: The long-term success of a startup requires founder continuity long past the point when conventional wisdom says the founders should be replaced. Startups at the end of the Customer Development process are not just nascent large companies waiting to shed their founders so they can grow. They are small companies that need to innovate continually so they can become large, sustainable businesses.

This makes the demise of an entrepreneur just as his or her company begins to succeed a Shakespearean tragedy. Why do some founders do so well in building a company but fail to grow with it? Why do some companies survive the Customer Development process but never manage to capitalize on their initial success? What do the winners have that the losers don't? Can we quantify and describe those characteristics?

Entrepreneurs like Mark believe getting the company to the next stage means simply doing more of the same. As Mark found out, an entrepreneur's tenure can have a more ignominious end. On the other hand, many investors believe all they need to do is bring in professional management to implement process and harvest the bounty. Both are wrong. The irony is that just when investors need to keep the company's momentum and flexibility going to reach mainstream customers, they stumble by substituting bureaucracy, while entrepreneurs fail to adapt their management style to the very success they have created.

Mark's debacle at BetaSheet reflects the lack of deliberation on the part of both the founding entrepreneur and the board about the company-building steps that transform a startup from a company focused on Customer Development into a larger company with mainstream customers. This evolution requires three actions:

- Build a mainstream customer base beyond the first earlyvangelist customers

- Build the company's organization, management, and culture to support greater scale

- Create fast-response departments to sustain the climate of learning and discovery that got the company to this stage

Concurrently, the company cannot rest on its laurels and become internally focused. To stay alive, it must remain alert and responsive to changes in its external environment, including competition, customers, and the market.

Building a Mainstream Customer Base

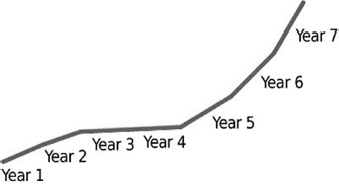

At first glance, the only apparent difference between a startup and a large company is the amount of customer revenue. If only it were that simple. The transition from small startup to larger company is not always represented by a linear sales graph. Growing sales revenue requires reaching a much broader group of customers beyond the earlyvangelists. And building this mainstream customer base requires shaping your sales, marketing, and business strategies on the basis of the Market Type in which you are competing.

Once again, Market Type is key. Just as this fundamental strategic choice shaped your choices in finding and reaching earlyvangelists, it will now shape how your company will grow and how you will allocate resources to do this. That's because each of the four Market Types has a distinctive sales growth curve shaped by the degree of difficulty involved in transitioning sales from the earlyvangelists to mainstream customers.

The sales growth curves in Figure 6.1 for a new market and an existing market illustrate the difference. Even after finding and successfully selling to earlyvangelists, the rate of sales differs in later years because of the different adoption rates of mainstream customers.

Figure 6.1 New Market Versus Existing Market Sales Growth Curves

This means that the activities you perform in Company Building, just like the activities in earlier steps, depend on the Market Type. Most entrepreneurs whose companies have reached this stage breathe a sigh of relief, thinking their journey is over and the hard work is behind them. They have found their customers and created a repeatable sales roadmap. Now all they need to do is hire additional sales staff. This common wisdom is incorrect. The most dangerous trap is a lack of understanding about Market Types. Market Type predicts not only how this transition will occur but also the type of staffing, hiring, and spending you will need.

Moore's insight is that early adopters (earlyvangelists, in our lingo) are not high-volume mainstream buyers. So success with early sales does not provide the sales roadmap for later mainstream buyers. Moore posits that a company must come up with new sales strategies in order to bridge the chasm. (See Figure 6.2.)

Figure 6.2 Technology Life Cycle Adoption Curve and Customer Development

Customer Development is on the left-hand side of the adoption curve. The chasm is the gap in sales revenue that occurs when sales to earlyvangelists do not smoothly transition into mainstream sales. The width of the gap varies dramatically with the Market Type, which explains the different sales growth curves for each Market Type. So why did we spend all this time in Customer Development if most of our customers will be in the mainstream market? You'll see Moore's chasm-crossing strategy builds on what was learned from these early customers to develop a much larger, mainstream customer base. We'll see how this works with Market Type in the discussion of Phase 1.

Building the Company's Organization and Management

As a company scales its revenue and transitions from early to mainstream customers, the company itself needs to grow and change as well. The most important changes are, first, in the overall corporate management and culture and, second, in the creation of functional departments.

Mission-centric Organization and Culture

Most startups don't give much thought to organization and culture, and if they do, it may have something to do with Friday beer bashes, refrigerators full of soft drinks, or an iconoclastic founder. Entrepreneurs and their investors tend to assume success means they must transform themselves as quickly as possible into a large company, complete with all the accoutrements of a large-company organization and culture: a hierarchical, command-driven management style, process-driven decision-making, an HR-driven employee handbook, and an “execution” mindset. The result is typically a bureaucracy imposed way too early. Such a system stems from the belief that imposing order and certainty on a disorderly, uncertain marketplace will result in predictable and repeatable success. (Paradoxically, pursuing order and certainty as a goal from the beginning would have meant the startup would never have gotten off the ground.)

In this final stage of Customer Development, the CEO, executives, and board need to recognize that with the uncertainty of the mainstream market still ahead of the company, just mimicking the culture and organization of a large company can be the beginning of the end for a promising startup. Consider what happened to BetaSheet four years after Mark left. With BetaSheet's early and visible success, the board was able to hire a traditional CEO experienced in the pharmaceutical business. She arrived just as the sales team missed its numbers. Customers were simply not adopting the product as rapidly as expected. The new CEO cut back the sales staff dramatically and replaced the VP of Sales. Then she looked at the rest of Mark's management team and replaced them one-by-one with a new team of experienced sales, marketing, and Product Development executives from much larger companies.

After that rocky start, sales and the company continued to grow for the next 18 months. BetaSheet's once radical ideas garnered acceptance in the pharmaceutical industry, and revenue was once again meeting plan. The board and investment bankers began to talk about an IPO. However, unseen by the BetaSheet management team, dark clouds were gathering on the horizon.

As large BetaSheet customers understood how strategically important this drug discovery software was, they began to set up their own in-house groups to provide it for themselves. Further, BetaSheet's new market creation activities had not only educated customers but also helped competitors understand how lucrative this new opportunity could be. Finally, while early customers were enthusiastic and supportive, revenue wasn't growing at the rate early sales successes had predicted. At the same time, new competitors and existing companies were starting to develop and offer similar products.

Internally, things were also changing. Not only had Mark left the company, but after 18 months an exodus of the most innovative engineering and sales talent began. The word among employees was that initiative and innovation were not appreciated; all decisions needed senior management approval. It became understood “not going by the book” was now a career-limiting move at BetaSheet. Moreover, by the third year, infighting between Sales and Product Development, and between Sales and Marketing, was almost as intense as battles with competitors. The BetaSheet departments each had their own agendas, at times mutually exclusive. New products never seemed to make it to market as priorities changed monthly. The sales decline, which began in year three, became a rapid death spiral in the fourth year. By its fifth anniversary the company shut its doors.

For a startup on such a fast track the BetaSheet story is depressing, but it's not unique. Replacing entrepreneurial management with process-oriented executives who crater the company happens all the time. The problem is that most founders and investors seem to have no alternative for organization and culture than the extremes of startup chaos and corporate rigidity.

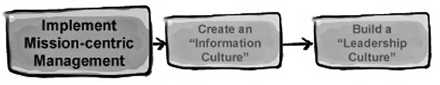

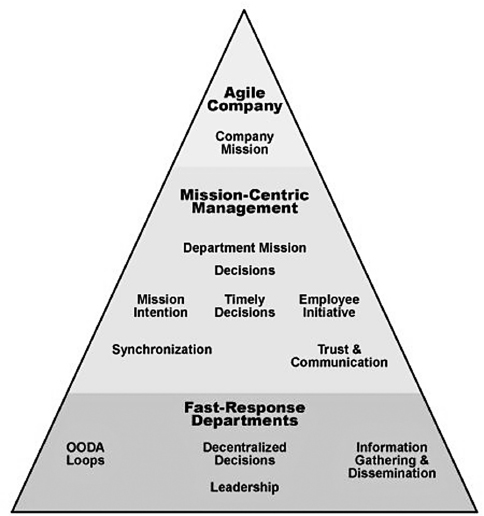

In this chapter I propose a third alternative. As it grows, a successful startup moves its company organization and culture through three distinct stages (see Figure 6.3).

Figure 6.3 Stages in the Evolution from Startup to Large Company

The first stage, which spans Customer Discovery, Customer Validation, and Customer Creation, is centered on the Customer and Product Development teams. The second stage happens in Company Building: The organization becomes mission-centric in order to scale up and cross the chasm between early and mainstream customers. When the company grows larger, it becomes process-centric to build repeatable and scalable processes.

Experienced executives understand process, but few of them understand what it means to be mission-centric. To make the transition to a large organization and cross the chasm, your startup must become an agile company, one that can still respond with entrepreneurial speed, but do so with a much larger group of people. Creating that agility requires a written and widely understood corporate mission that drives the day-to-day operations of the departments and the employees. As you'll see in Phases 2 and 3, this mission-centric mantra must pervade the culture of the entire company.

For the organization to grow, these transitions must occur. If the members of the founding team want to continue their tenure with the company, they must also make these transitions. They need to recognize the shifts in emphasis, embrace them, and lead the change in management style. At BetaSheet, Mark failed to understand this evolution, and both he and the company paid the price.

Transforming the Customer Development Team into Functional Organizations

If you've followed the Customer Development model to this point, you've already built your first mission-centric team. In Phase 3 of this step you will transform the mission-oriented culture of the Customer Development team into departments organized to execute and support the corporate mission.

Don't mistake this as building departments that then invent missions to justify their existence. Too many startups interpret growth as a call to build, staff, and scale traditional departments according to a cookie-cutter model (thinking all companies must have Sales, Marketing, Business Development) rather than building a structure from a clear strategic need. In contrast, in the Customer Development model, the next step is to add a layer of management and organization still focused on the customer-centric mission, not just on building departments and headcount. You want to achieve a management system and departments that communicate and delegate strategic objectives to the staff so they can operate without direct daily control while still pursuing the same mission.

This can be achieved only if executives are selected because they share the same values, not just because their resumes show lots of experience. At the same time, this next layer of management needs to be made up of people who are leaders in their own right, not just yes-men to a charismatic founder. As leaders, they transmit the company's vision to all the people who help carry it out. I learned this principle early on in my career, when I took over as VP of Marketing at SuperMac, a company just exiting Chapter 11. I asked my department managers what their mission was. Their responses were disconcerting. Our head of the trade show department responded, “My mission is to set up our trade show booths.” The other managers gave the same kinds of answers. The head of the public relations group said he was there to write press releases. The leader of the Product Marketing Department said his job was to write data sheets and price lists. When I pressed them to think why Marketing was going to trade shows, or writing press releases or penning data sheets, the best I could get was “because that's our job.” A lack of clarity about mission is always a leadership failure. Soon thereafter, I began to educate my staff about their mission. It took a year to get a department of people who understood their business card title might be their daily function, but it wasn't their job. The mission of Marketing at SuperMac was to:

- Generate end-user demand

- Drive that demand into our sales channels

- Educate our sales channels

- Help Engineering understand customer needs

These four simple statements helped Marketing organize around a shared mission (which we all recited at the beginning of our staff meetings). Everyone else in the company knew what we in Marketing were going to do all day, and how to tell whether we succeeded. You'll see how the Customer Development team morphs into mission-driven functional organizations in Phase 3.

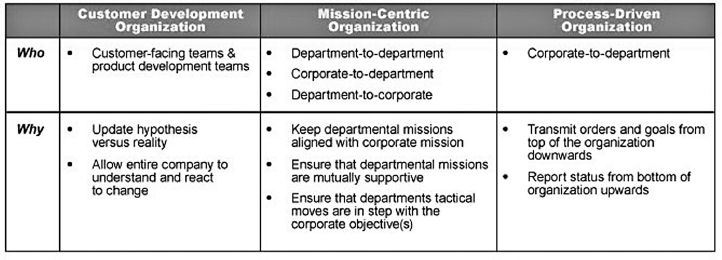

Creating Fast-Response Departments

Customer Development and a mission-centric organization call for doing different things from day to day, because in a learning and discovery organization, change and the reaction to change are the only constants. In contrast, “a process-driven organization” is designed to repeat things that have been found to work with little change. When it's successful its constant is sameness from day to day—no surprises, no rapid shifts.

Process is essential for setting measurable goals and establishing repeatable procedures that do not require experts to implement. Process is how large companies can grow larger, how they can scale departments and the company without hiring superstars. Large companies can hire thousands of average employees who can follow the rules and check to see whether the business is proceeding according to plan. Process in an organization means procedures, rules, measurements, goals and stability.

Everything about process is anathema to most entrepreneurs, who in their gut believe success shouldn't require process. Yet they rarely have anything to offer in its place. Now they do: the “fast-response” department.

Creating fast-response departments offers a natural evolution from the learning and discovery stage to the functional departments a large company needs. Fast-response departments keep the company agile and avoid rigor mortis. We'll look at fast-response departments in detail in the discussion of Phase 4.

Overview of Company Building

Figure 6.4 Company Building: Overview of the Process

Company Building has four phases. In Phase 1, you set the company up for its next big hurdle, transitioning sales from earlyvangelists to mainstream customers, by matching the appropriate sales growth curve to hiring, spending and relentless execution.

In Phase 2, you review the current executive management and assess whether the current team can scale. In this phase you devote a lot of attention to creating a mission-centric organization and culture as an essential means of scaling the company.

In Phase 3, capitalizing on all the learning and discovery the company has done to date, the Customer Development team realigns into departments by business function. Each department gets reoriented to support the corporate mission by developing its own departmental mission.

Finally, in Phase 4, at the end of Customer Development, the company works to create fast-response departments for scale, speed, and agility. Here you use the military concept of OODA (Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act) by moving and responding to competitors and customers at a tempo much faster than your competition. This requires departments to have at their fingertips up-to-date customer information and to be able to rapidly disseminate that information across the company.

Phase 1: Reach Mainstream Customers

It's been a long journey through Customer Development. This phase is the culmination of all your hard work in building a successful startup. By now you have early customers, you've positioned your company and product, and you're on the way to creating demand for what you're selling. All this is in preparation for reaching the high-volume mainstream customers who can transform your startup into a dominant player in your market.

As I've noted, the extremely useful notion of a chasm between early adopters and mainstream customers needs to be supplemented with the understanding that the width of the chasm and the time frame for crossing it depend on the Market Type in which you're operating. Accordingly, this section describes the differences in customer transitions and sales-growth curves in a new market, an existing market, and a resegmented market. An understanding of the customer transition and sales growth by Market Type will allow your company to forecast the timing of mass market adoption, hiring and cash-burn needs, and other essential factors in growing the company appropriately. The sales-growth curve describes the how; the chasm explains the why.

This understanding is essential to your efforts to reach mainstream customers. In this phase you will:

- Manage the transition from earlyvangelists to mainstream customers, understanding how the transition differs by Market Type

- Manage the sales-growth curve appropriate for your company and Market

Type The outcome of this phase is twofold: (1) a chasm-crossing strategy that fits the Market Type and (2) a revenue/expenses plan and a cash-needs plan matching the Market Type.

A. Transitioning from Earlyvangelists to the Mainstream in a New Market

In a new market, the motivations of early buyers and mainstream customers are substantially different. The earlyvangelists you've targeted in Customer Validation want to solve some immediate and painful problem or, in the case of companies, gain a large competitive advantage by purchasing a revolutionary breakthrough. The majority of customers, however, aren't earlyvangelists; they're pragmatists. Unlike earlyvangelists, they typically want evolutionary change. Consequently, the effort you have put into building a repeatable and scalable sales process for earlyvangelists will not lead you to volume sales. Visionaries will put up with a product that doesn't quite work; pragmatists need something that doesn't require heroics to use. Further, pragmatists do not care for or trust the visionaries as references. Pragmatists want references from other pragmatists. The chasm between earlyvangelists and volume sales to mainstream customers occurs because these two groups of customers have little in common.

In a new market, the gap between visionary enthusiasm and mainstream acceptance is at its widest point (see Figure 6.5). The width of the gap explains the hockey-stick sales growth curve often seen in a new market: a small blip of revenue in the first year or so from sales to earlyvangelists and then a long, flat period, or even a dip, until the sales force learns how to sell to a completely different class of customers and Marketing convinces pragmatists your new product is worth adopting.

Figure 6.5 The Chasm in a New Market

In addition to the long hiatus until sales take off, a new market has the most serious sales risks on either side of the chasm. On the near side of the chasm, finding a repeatable sales process for earlyvangelists might succeed all too well. Your sales organization might become content with the relatively low level of repeatable business. In fact, the sales force may exhaust the visionary market by selling to all potential earlyvangelists without having prepared to learn the new sales roadmap for reaching mainstream customers.

The risk on the other side of the chasm is that you may never get there. Mainstream pragmatists in a new market may see no reason to start adopting your product. Especially in tough economic times, few customers want to be innovators if they can help it. When spending is tight, new companies with innovative ideas find the mainstream a formidable and sometimes impenetrable customer base.

There is another risk as well—your competition. After years of investing in educating a new market about the benefits of your product, your startup could lose to a “fast-follower”—a company that enters the market, piggybacks on top of all your market education, crosses the chasm, and reaps the rewards. Usually, startups lose to a company that has implemented a fast-response organization and is learning and discovering faster than they can.

While these risks may sound catastrophic, they don't have to be. The biggest danger is not understanding the characteristics of new-market customers—or worse, recognizing them but refusing to risk changing the sales model that has produced your earlyvangelist sales in order to go after the volume customers. That can be a first-order tragedy for your investors and company.

To reach mainstream customers in a new market, your company must devise selling and marketing strategies that differ from those used in an existing or resegmented market. For example, rather than simply hiring lots of salespeople to capture hordes of customers (as in an existing market), you must find the sparse population of earlyvangelists and use them to gain a foothold in the mainstream market. Rather than spending large sums on a branding campaign (as in a market you are trying to resegment) to an audience that is not ready to listen, you need to use the few yet potent earlyvangelists to woo and win the mainstream market.

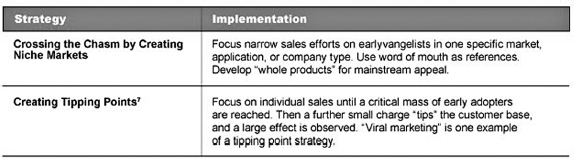

Two of the best-known strategies are (1) “crossing the chasm” by finding niche markets 1 and (2) creating a “tipping point.” 2 These strategies are summarized in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Earlyvangelist to Mainstream Customer Strategies in a New Market

While both strategies have been widely discussed, their implementation by startups has not always been successful. My contention is these strategies work best when applied in new markets, not all markets. Chasm-crossing and tipping point are best suited for converting a small cadre of true believers into a mass movement. Chasm-crossing builds upon initial earlyvangelist sales by targeting your sales force to focus on a single reference market, application, industry, or company type (the niche), then selling to the mainstream economic buyers. These mainstream buyers need a “whole product” (a complete solution). Tipping point strategies work differently (they are sometimes compared to how epidemics spread). They capitalize on the observation that just a few “right” people can create a change in customer and market behavior. That once a critical mass of these right people endorse a product, particularly one that is “sticky,” mass adoption can occur at an exponential rate. When the tipping point strategy is applied to a company or product, the goal is to artificially create the herd effect by managing customer perceptions of an inexorable trend.

B. Managing Sales Growth in a New Market

For years venture capitalists have realized startups in new markets take an extended time to reap the rewards. VCs refer to these startups as having a hockey-stick rate of sales growth. As illustrated in Figure 6.6, while there may be a blip in sales revenue from earlyvangelist orders, in a new market sales can be close to zero during the first few years. Revenue accelerates to exponential growth only when the company successfully educates customers, creates new sales and channel roadmaps that reach mainstream customers, and has the staying power and resources for the long haul.

Figure 6.6 New Market Sales Growth—The Hockey Stick

Besides being a sobering predictor of life without much revenue, this sales growth curve sets several important parameters for a startup in a new market with no sales revenue coming in:

- Capital requirements: How much money will the company need to raise until revenue starts coming?

- Cash flow/burn rate: How does the company manage its cash and burn rate?

- Market education/adoption plan: How much education will it take, and how long will it take for the market to grow to sufficient size?

- Hiring plan: If infinite marketing dollars will not affect demand in a new market, why and when does the company need to staff a marketing department? The same question applies to the sales staff. If revenue is not elastic based on the number of salespeople in the field (but rather depends on the creation of the market), why and when does the company staff the sales organization?

The implication of these questions is that in a new market Company Building is all about husbanding resources and passionately evangelizing and growing the market until the market grows large enough for sales revenue to appear. Your experience of selling to earlyvangelists during Customer Validation will help you answer, “How many of these early customers can your company really find in the first few years?” That question will help you set your sales revenue and expense model, and give you a feeling of the cash needed until the “hockey stick” sales curve driven by mainstream customers kicks in.

One last risk in entering a new market is the market itself turns out to be a chimera. In other words, there may simply not be enough customers past the initial early adopters to sustain a large business. Worse, most companies don't find out they were wrong until years later when they are out of money. By then it is too late to reposition the company. Some examples of new markets that never materialized are home dry-cleaning products, low-fat substitutes for snack products, “smart cards” (credit cards with a computer chip in them), the artificial intelligence market in the early 1980s, and the pen computing market in the early 1990s. Therefore before selecting a new market as a positioning choice, entrepreneurs and their companies ought to look at their projected burn rate, look deep into the eyes of their investors and cofounders, and make sure this is the path everyone agrees to travel together willingly.

C. Moving from Earlyvangelists to the Mainstream in an Existing Market

In an existing market, the chasm between earlyvangelists and mainstream customers is small or may not exist (see Figure 6.7). That's because the visionaries and pragmatists are the same type of customer. In an established market, all customers will readily understand your product and its benefits.

Figure 6.7 The Chasm in an Existing Market

There is no long interregnum as the sales organization learns a new sales roadmap and a new class of customers gets educated. The only limits on sales growth are market share and differentiation. The absence of a chasm is a signal that this market is ripe for exploitation and relentless execution. The challenge is while customers may understand your product and benefits, they may not understand why they should buy your product rather than one from a familiar existing company.

This is where positioning 3 and branding 4 come into play. Positioning and branding are well-known strategies for differentiating companies and products. At times these two words are used synonymously, which is a problem since they are different, and the difference matters. In an existing market, where market share is the objective and there is little distinction among competitors, the fastest and least expensive way to differentiate your company and product is to establish positioning, or value (i.e., everyone knows why your product is better and wants it) rather than pursuing branding (everyone knows about your product and thinks your company is wonderful). Positioning can be considered successful when customers not only recognize the product or service but can recite its attributes. When positioning is executed correctly, it creates end-user demand for the product. For example, Starbucks is the No. 1 place for coffee is the Starbucks positioning. In contrast, branding works best when you are resegmenting a market. Starbucks is a great company and treats its employees well is Starbucks positioning the company. Spending money on branding in an existing market may mean potential customers know who your company is, but still end up buying from a competitor.

D. Managing Sales Growth in an Existing Market

In an existing market, Customer Validation and Creation should have already proven there are willing customers who understand your startup's unique advantages. Hopefully, Marketing has differentiated the product and is now creating end-user demand and driving it into your sales channel. The sales organization is scaling to reap the rewards. If all goes well, the graph of year-to-year sales in an existing market is a nice straight line (Figure 6.8). And the table you put together is a standard sales and marketing forecasting and hiring plan.

Figure 6.8 Sales Growth in an Existing Market

If you're lucky enough to be in this Market Type and at this stage, scaling means worrying about:

- Capital requirements: How much money needed until cash flow break even?

- Hiring plan: Can the company scale rapidly enough to exploit the market?

- Product lifecycle: Your nice linear sales curve is true only as long as your product remains competitive. Are there follow-on products in your pipeline?

- Competitive responses: Most competitors will not stay unresponsive forever. What happens when they respond?

In an existing market, then, Company Building is about pursuing relentless execution and exploitation of the market, while simultaneously being intensely paranoid about your product lifecycle and the responses of competitors. (Think of the myriad car manufacturers who began producing SUVs after the Chrysler Minivan created a mass market in the 1970s.) The density and intensity of this Market Type means the linear upward sales curve can easily reverse direction.

E. Moving from Earlyvangelists to Mainstream Customers in a Resegmented Market

A resegmented market strategy lands your company somewhere between a new market and an existing market. Although the chasm between earlyvangelists and mainstream customers is not as wide as in a new market (Figure 6.9), it takes time to convince mainstream customers that what you have defined as unique about your product or company is a compelling selling proposition. As a result, in the early years, sales may be low.

Figure 6.9 The Chasm in a Resegmented Market

There are two chasm risks in this Market Type. First, is the seductive nature of sales to early adopters. In this Market Type, there are sufficient visionary customers to generate revenue, albeit at a small scale, to make the company think it has built a scalable business model. The reality is the company is skimming a low volume of sales from a competitive existing market. Crossing the chasm in this Market Type means attracting masses of mainstream customers who need to be educated to what's new and different about the way you've redefined the market. In other words, you have some of the same issues as a company entering a new market. However, instead of using niche marketing and tipping point strategies as you would in a new market, you use branding and positioning to reach mainstream customers. It is here, in a resegmented market, that all the conventional wisdom about branding and positioning is actually valid. Marketers use these tactical tools to differentiate their company and product from those in an existing market. For example, in the home appliance market, Subzero, Miele and Bosch created a new segment of kitchen appliances: high-end and feature-laden. Consumers (at least in the U.S.) were perplexed about why they should pay exorbitant prices for what were “just” refrigerators, washers, and dryers. However, after some time, adroit marketing and positioning took hold, and these previously mundane appliances turned into status symbols. Similar examples of successful resegementation can be found across a wide variety of industries: Starbucks transforming the 49-cent cup of coffee into the $3 latte; Dell turning commodity personal computers into build-your-own, custom-designed products; Perrier and Calistoga turning water, the ultimate commodity, into a high-end purchase that costs more than gas.

This litany of success stories brings us to the second risk in a resegmented market—resegmenting an existing market typically is expensive, and companies require sufficient capital for seeing an adroit marketing and positioning through to completion. While there may be a ready existing market for your company to reach and resegment, your messages need to be heard above the cacophony of the incumbents. Startups that resegment typically underestimate the dollar and time commitments necessary to make a lasting impression on the consumer psyche.

In Customer Creation, I pointed out that one of the key marketing mistakes is having an ad or PR campaign that lacks an underlying positioning strategy. Having a positioning strategy is the prerequisite to branding. Too many VPs of Marketing choose a branding campaign when they cannot even articulate a position. Branding is expensive, time-consuming, and designed to elicit a visceral reaction. The key in a market you are resegmenting is to use positioning to establish the value of the new segment and create demand for a product. Then you can use branding to reinforce the value of that segment and grow demand exponentially into the hockey-stick part of the sales curve.

To reiterate: Branding and positioning strategies, while widely popularized, have been misused by many startups. In a new market, these strategies are expensive and deadly (they were the sinkhole for most dot-coms). They are critical, however, in a market you are resegmenting. In a resegmented market, you use branding and positioning to turn a small cadre of early evangelists into a mass market, yet have the customers in that mass market believe they remain a small, elite group.

F. Managing Sales Growth in a Resegmented Market

Sales growth in a resegmented market is a complicated balancing act, since it combines the sales growth models of new and existing markets. The good news is there is an existing market of customers who will readily understand what the product is. This allows the company to immediately generate some level of sales even amid stiff competition. However, these early sales should not be confused with success. The company won't achieve explosive sales growth until the market understands and adopts its resegmentation. The result is the sales curve shown in Figure 6.10. The sales-growth issues that need to be managed in a resegmented market are these:

- Capital requirements: How much money is needed until cash flow break-even?

- Market education costs: Can the company afford the continued cost of educating and creating this new segment?

- Positioning and branding costs: Unlike a new market, a resegmented market offers a clear target to be different from. This positioning and branding are costly. Is there a budget?

- Hiring plan: Can the company balance early sales without overhiring before the ramp appears?

- Market evaluation: What happens if resegmentation doesn't work? Most startups end up in the land of the living dead. How do you avoid it?

Figure 6.10 Sales Growth in a Resegmented Market

In short, Company Building in a resegmented market is similar to Company Building in a new market. It is about husbanding resources and passionately evangelizing and growing the new market segment until the segment is large enough for hockey-stick sales revenue to appear. As with a new market, one of the risks is the new segment can be a chimera. In this case, you're left trying to make it against multiple competitors in an existing market with a product that isn't significantly unique.

Phase 2: Review Management and Build a Mission-Centric Organization

Company Building prepares the company to move from an organization focused on learning, discovery and attracting earlyvangelist customers to one putting all its resources into finding and acquiring mainstream customers. For this to happen, you need to ensure your senior management can lead this critical transition.

The appraisal of the executive team may be a wrenching shift for individuals and the entire company. The process must be guided and managed by the board. In this phase, you will:

- Ask the board to review the CEO and the executive staff

- Develop a mission-centric culture and organization

A. The Board Reviews the CEO and Executive Staff

When you reach the company-building step, it's time for the board to look inward and decide whether the current CEO and executive staff are capable of scaling the company. To get here, the company needed people like Mark at BetaSheet: passionate visionaries capable of articulating a compelling vision, agile enough to learn and discover as they went, resilient enough to deal with countless failures, and responsive enough to capitalize on what they learned in order to get early customers. What lies ahead, however, is a different set of challenges: finding the new set of mainstream customers on the other side of the chasm and managing the sales growth curve. These new challenges require a different set of skills. Critical for this transition are a CEO and executive staff who are clear-eyed pragmatists, capable of crafting and articulating a coherent mission for the company and distributing authority down to departments that are all driving toward the same goal.

By now, the board has a good sense of the skill set of the CEO and executive team as entrepreneurs. What makes the current evaluation hard is that it is based not on an assessment of what they have done, but on a forecast of what they are capable of. This is the irony of successful entrepreneurial executives: Their very success may predicate their demise.

Table 6.2 helps elucidate some of the characteristics of entrepreneurial executives by stage of the company. (Looking at this table, what should the BetaSheet board have done about Mark?) One of the most striking attributes of founding entrepreneurial executives is their individual contribution to the company, be it in Sales or Product Development. As technical or business visionaries, these founding executives are leaders by the dint of their personal achievements. As the company grows, however, it needs less of an iconoclastic superstar and more of a leader who is mission-and goal-driven. Leaders at this stage must be comfortable driving the company goals down the organization, and building and encouraging mission-oriented leadership on the departmental level. This stage also needs less of a 24/7 commitment from its CEO and more of an as-needed time commitment to prevent burnout.

Table 6.2 CEO/Executive Characteristics by Stage of the Company

Planning is another key distinction. The learning and discovery stage called for opportunistic and agile leadership. As the company scales, it needs leaders who can keep a larger team focused on a single-minded mission. In this mission-centric stage, hierarchy is added, but responsibility and decision-making become more widely distributed as the span of control gets larger than one individual can manage. Keeping this larger organization agile and responsive is a hallmark of mission-oriented management.

This shift from Customer Development team to mission-centric organization may be beyond the scope or understanding of a first-time CEO and team. Some never make the transition from visionary autocrats to leaders. Others understand the need for a transition and adapt accordingly. It's up to the board to decide which group the current executive team falls into.

This assessment involves a careful consideration of the risks and rewards of discarding the founders. Looking at the abrupt change in skills needed in the transitions from Customer Development to mission-centric organization to process-driven growth and execution, it's tempting for a board to say, “Maybe it's time to get more experienced executives. If the founders and early executives leave, that's OK; we don't need them anymore. The learning and discovery phase is over. Founders are too individualistic and cantankerous, and the company would be much easier to run and calmer without them.” All this is often true – particularly in a company in an existing market, where the gap between early customers and the mainstream market is nonexistent, and execution and process are paramount. A founding CEO who wants to chase new markets rather than reap the rewards of the existing one is the bane of investors, and an unwitting candidate for unemployment.

Nevertheless, the jury is out on whether more startups fail in the long run from getting the founders completely out of the company or from keeping founders in place too long. In some startups (technology startups, especially), product lifecycles are painfully short. Regardless of whether a company is in a new market, an existing market, or a resegmented market, the one certainty is that within three years the company will face a competitive challenge. The challenge may come from small competitors grown bigger, from large companies that now find the market big enough to enter, or from an underlying shift in core technology. Facing these new competitive threats requires all the resourceful, creative, and entrepreneurial skills the company needed as a startup. Time after time startups that have grown into adolescence stumble and succumb to voracious competitors large and small because they have lost the corporate DNA for innovation, and learning and discovery. The reason? The new management team brought in to build the company into a profitable business could not see the value of founders who kept talking about the next new thing and could not adapt to a process-driven organization. So they tossed the founders out. And paid the price later.

In an overheated economic climate, where investors could get their investments liquid early via a public offering, merger or acquisition, none of this was their concern. Investors could take a short-term view of the company and reap their profit by selling their stake in the company long before the next crisis of innovation occurred. However, in an economy where startups need to build for lasting value, boards and investors may want to consider the consequences of not finding a productive home to hibernate the creative talent for the competitive storm that is bound to come.

The concepts of mission-oriented leadership and fast-response organization developed in this chapter offer investors and entrepreneurs another path to consider. Instead of viewing the management choices in a startup as binary—entrepreneur-driven on Monday, dressed up in suits and processes on Tuesday—mission-oriented leadership offers a middle path that can extend the life of the initial management team, focus the company on its immediate objectives, and build sufficient momentum to cross the chasm.

B. Developing a Mission-Centric Organization and Culture

The consequence of not having a common mission was clear at BetaSheet. Mark led the company through Customer Discovery and Customer Validation, and he had the scars to prove it. In Mark's mind, he had a singular vision for BetaSheet and was keeping his eyes fixed on where he saw the company going. However, one of his fundamental mistakes was in failing to ensure that his board and executive staff, to say nothing of the rest of the company, shared his vision. The new executives Mark hired to run Sales, Marketing, and Engineering acted like hired guns rather than committed owners. Part of this was Mark's fault in not selecting his hires for commitment to his vision rather than the length of their resume. Part of it was the fault of Mark's board in not teaching him the value of hiring executives who shared his vision. In fact, one of Mark's board members reinforced this lack of commitment in the executive staff by offering up a candidate for VP of Sales whose main qualification was that he was marking time in the board member's office. Finally, part of the problem was Mark should have been communicating and evangelizing his vision inside the company as effectively as he was doing outside. As BetaSheet scaled up, Mark's board, his executive staff, and his employees all could have shared the same worldview. Instead, the end was marked by dissonance not only about style, but about what made the company unique.

Stating Your Corporate Mission

So how do you avoid Mark's error and make the mission part of the lifeblood of your company? At the heart of the mission-centric organization is the corporate mission statement. Most startups put together a mission statement because the executive staff remembered seeing one at their last job, and somehow it felt important. Or perhaps their investors told them they needed a mission statement for their PowerPoint presentations. In neither case was a mission statement something the company lived on a daily basis.

Where does a “lived” mission statement come from? You just finished the long, laborious process of Customer Discovery, Validation, and Creation deriving, testing, and executing your mission. The mission statement you craft now is a further refinement of one you first proposed in Customer Discovery, revisited in Customer Validation, and tested with customers in Customer Creation. The goal of the earlier mission statements was to help customers understand how your company and products are unique. You may have embedded this mission on your company website, and your salespeople may have put it in their presentations. The mission statement you need in the company-building stage is different. It's for you and your company, not your customers. It consists of a paragraph or two that tells you, your board and your employees how you will cross the chasm from earlyvangelists to mainstream customers and manage the sales growth curve. It tells everyone in specific terms why they come to work, what they need to do, and how they will know they have succeeded. And it mentions the two dirty words that never get presented in mission statements that customers see: revenue and profit.

An example of a clearly written mission statement is the one “lived” at CafePress, a company that allows individuals and groups to easily create their own store to sell T-shirts, coffee cups, books and CDs.

- At CafePress our mission is to allow customers to set up stores to sell a wide range of custom products. (Our goal is to make sure they say we are the best place to go on the Web to make and sell CDs, book, and promotional items.) Here's how we are going to do that:

- We are going to give them a variety of high-quality products and good service in an easy-to-use website. (We will know we succeed if an average store sells $45 per month.). At the same time we will help these customers sell by giving them marketing tools to reach their customers

- We are going to do it for what they would consider a fair price (yet maintain 40% margins.) Next year our plan is to grow to $30 million in revenue and be profitable. (Therefore we need 25,000 new customers a month)

- We are going to try to be a good citizen of our community. (We are going to print on recyclable materials, use environmentally friendly packaging, and use nontoxic inks wherever practical)

- We are going to take good care of our employees (full medical and dental) because the longer they stick around, the better our company will become

- We are also going to offer stock options to all employees, because if they're interested in our profits and long-term success we'll all make money

Read this mission statement sentence by sentence. It tells the employees why they come to work, what they need to do, and how they will know when they're successful.

Crafting Your Corporate Mission Statement

Most companies spend an inordinate amount of time crafting a finely honed corporate mission statement for external consumption and then do nothing internally to make it happen. What I'm describing here is quite different. First, the corporate mission statement you develop now is for use inside the company. You may use some version of it to make your customers and investors happy, but that is not its purpose. Second, the mission statement is action-oriented. It is written to provide daily guidance for all employees. For that reason, it is focused on execution and what the company is trying to achieve. If you do it right, your corporate mission statement will help employees decide and act locally while being guided by an understanding of the big picture.

Crafting this “operational” mission statement is a visible sign of the transition in management from entrepreneurial to mission-centric. The CEO uses this opportunity to get commitment and buy-in from all the operating executives (as well as any of the remaining founders who may be in non-operational roles). If needed, the CEO may bring in other employees to ensure the statement is both shared and grounded. The board needs to be involved in the process as well, both to provide input and give final approval.

Figure 6.11 shows a rough template for drafting a corporate mission statement based on the one for CafePress. As you write (and rewrite) your mission statement, remember there are no right and wrong answers. The litmus test is this: Can new hires read the corporate mission statement and understand the company, their job, and what they need to do to succeed?

Figure 6.11 Template for Drafting a Corporate Mission Statement

Keep in mind a mission statement for a company executing in an existing market will be quite different from a company in a new or resegmented market. In an existing market, the mission statement reflects the goal of straight-line sales growth. It describes how the company executes relentlessly to exploit the market while remaining paranoid about product lifecycle and competitors. In a new market, the company mission statement reflects the hockey-stick growth curve, and it emphasizes husbanding resources and passionately evangelizing and growing the market. In a resegmented market the mission statement describes the branding and positioning work necessary to create a unique and differentiated image of the company.

Following Through

The corporate mission statement is essential, but it's just a start. The mission-centric culture must embrace the entire company, not just the departments dealing with customers. For this reason the executive team needs to make an intense effort to ensure members of all departments feel they share a common purpose. This requires constant communication across the company. In Phase 4, you'll carry the mission-centric process further by having each department craft its own departmental mission statement. These departmental statements will answer the same three questions as the corporate mission statement—why people come to work, what they are going to do all day, and how they will know they have succeeded— in terms of the goals and activities of the specific department.

Phase 3: Transition the Customer Development Team into Functional Departments

Phase 3 of Company Building signals the end of Customer Development teams and the shift to formal departments. Through constant interaction with earlyvangelist customers in Steps 1 through 3, the Customer Development team has discovered how to build repeatable sales and channel roadmaps. With these completed, the focus shifts to acquiring mainstream customers. This requires more than a small group of people to execute. Unfortunately, a Customer Development team without functional organization cannot scale. To remedy this, the company now needs to organize into departments that aggregate specific business functions that would have been counterproductive in earlier stages—principally sales, marketing, and business development—and organize them appropriately to match the needs of the company's Market Type. Accordingly, in this phase, you will:

- Craft mission statements for departments organized around business functions

- Define departmental roles according to the Market Type

A. Crafting Departmental Mission Statements

Before you set up Sales, Marketing, Business Development, and other customer-facing departments, you must figure out what these departments should do. That might sound like a facetious statement. We all know what departments do: Sales hires people to go out and sell, Marketing hires a staff and writes data sheets and runs advertisements, and so on. But that's simply not true, because the goals of each department are different depending on the Market Type, as will be clear from the discussion in this section.

Before you formally set up those departments, therefore, it's incumbent on the executive staff to think through what each department's goals will be and to articulate those goals in the form of departmental mission statements. The reason for doing this before you start hiring and staffing is that existing departments tend to rationalize their own existence and activities. Very few vice presidents in the annals of corporate history have ever said, “I think my department and staff are superfluous; let's get rid of all of them.”

In Phase 2 you assembled a corporate mission statement that matched your Market Type. Your task now is to translate that corporate mission into departmental mission statements with objectives that are department-and task-specific. For example, a mission statement for a marketing department in an existing market might look like this:

The mission of our Marketing Department is to create end-user demand and drive it into the sales channel, educate the channel and customers about why our products are superior, and help Engineering understand customer needs and desires. We will accomplish this through demand-creation activities (advertising, PR, trade shows, seminars, websites, etc.), competitive analyses, channel and customer collateral (white papers, data sheets, product reviews), customer surveys, and market requirements documents.

Our goals are 40,000 active and accepted leads into the sales channel, company and product name recognition over 65% in our target market, and five positive product reviews per quarter. We will reach 35% market share in year one of sales with a headcount of five people, spending less than $750,000.

Figure 6.12 shows how the mission statement fits the template provided earlier for a corporate mission statement.

Figure 6.12 Sample Mission Statement for a Marketing Department in a New Market

It specifies exactly why people in this department come to work, what they need to do all day, how they will know they have succeeded, and what their contribution is to the company's profit goals. With this statement, I don't think employees will have any doubt about their mission.

B. Defining Departmental Roles by Market Type

Now that you have the mission statements for the departments, you can organize the departments themselves. Keep in mind the underlying risk in simply setting up departments by function. Now that you have a proven process for earlyvangelist sales and departments are being set up, the natural tendency is for senior executives to revert to form. The head of Sales says, “Finally, I can build my sales force”; the head of Marketing says, “Now I can hire a PR agency, run ads, and generate marketing requirements documents for Engineering”; and the head of Business Development says, “Time to do deals.” Nothing could be further from the truth. Each department needs to consider how its role is defined by the Market Type the company is facing. The following discussion considers the roles of Sales, Marketing, and Business Development in each Market Type.

Department Roles in an Existing Market

Until now, the role of Sales as part of the Customer Development team has been to confirm product/market fit, find repeatable sales and channel roadmaps, and secure the earlyvangelist customers and orders to prove the roadmaps and business model work. Now that you have a critical mass of early customers, the role of a sales department is, “Get more of those customers to scale revenue and the company.” That's because only in an existing market are the earlyvangelists and mainstream customers quite similar. Therefore you need to build a sales organization that can repeatedly and reliably execute from a known roadmap. This implies a sales compensation program that will incentivize the correct behavior—no wild swings for the fence, no new market forays, just day-to-day, relentless execution.

Organizing the marketing department presents the same challenges as Sales. Up until now, Marketing's role in Customer Development has been in learning and discovery—searching for new customer segments and niches, and testing positioning, pricing, promotion, and product features. Now Marketing's role shifts from creativity to execution. Since the sales organization at this point is all about repeatability and scale, all it wants from the marketing department are the materials that will support getting more customers. This means Marketing needs to drive demand into the sales channel by providing qualified customer leads, competitive analyses, customer case studies, sales training, channel support, and the like. This shift from strategist to tactical spearcarrier can be traumatic for the individual marketer or small marketing team that literally a month before was leading the Customer Development process, but it must be accomplished if Sales is to grab market share.

As Sales demands tactical execution, there's a danger Marketing will move its creative efforts to either marketing communications or product management. In the first case, the risk is that Marketing confuses its new function with simply being a marketing communications department, hiring PR agencies, branding the company, and so on. If the marketers are more technically oriented, the risk is that they will begin acting like product managers and start developing the Marketing Requirements Document (MRD) for the next product release. Mistakes like these are the natural tendency of creative people who no longer have a creative job. These mistakes are much more likely to happen in the absence of a clearly understood departmental mission tied to the corporate mission.

Regrettably, the dot-com bubble mutated the title “Business Development” into a barely recognizable role. Let's set one thing straight: Business development is not a 21st-century term for “sales.” Any time I find people in a company using it that way I stay far away, since if they are imprecise about this role, they are usually fuzzy about their financial numbers and the rest of their business. The real function of a business development group is to assemble the strategic relationships necessary to build the “whole product” via partnerships and deals so the company can sell to mainstream customers.

The “whole product” is a concept defined by Bill Davidow 5 in the early years of technology marketing. It says that mainstream customers and late adopters on the technology lifecycle adoption curve need an off-the-shelf, no-risk, complete solution. They do not want to assemble piece parts from startups.

In an existing market, your competitors define how complete your product offering needs to be. If your competitors have “whole products,” you need the same. In the computer business, for example, IBM is currently the ultimate supplier of whole products. It provides the hardware, software, systems integration support, and all the ancillary software to support a business solution. There is no way a startup just scaling up to compete in this space could offer a whole product. That wasn't a liability in the earlier stages of Customer Development, when the company was selling to earlyvangelists who were happy to assemble a whole product themselves. No mainstream customer, however, is going to buy a half-finished product. Consequently, the strategic mission of Business Development is to assemble a whole product to acquire mainstream customers. This means Business Development is a partnering and deal function, not a sales activity. Table 6.3 summarizes the objectives of each department in an existing market and the main ways those objectives are achieved.

Table 6.3 Roles of Departments in an Existing Market

Department Roles in a New Market

For Sales in a new market this is a confusing time. The hard-won lessons learned in Customer Validation are not transferable, since the mainstream customers are not the same as the earlyvangelists you've been selling to. Therefore, even with an infinite number of salespeople, sales revenue will not scale without a change in strategy.

A real risk for a sales department in a new market is to continue to believe that earlyvangelists represent the mainstream market. Earlyvangelist sales cannot provide the hockey-stick growth curve that will turn the startup into a large company. At this stage earlyvangelists sales shouldn't be discouraged (they provide the ongoing revenue), but they should be thought of as a segment the sales department must outgrow if the company is to succeed. As discussed in Phase 1 of this chapter, the task now is to use the earlyvangelists as a “beachhead” into a narrow market segment or niche, or as the fulcrum for a tipping point.

The job of Marketing in a new market is to identify the potential mainstream customers, understand how they differ from the earlyvangelists, and come up with a chasm-crossing strategy to reach them. The danger here is that Marketing will act as if it is in an existing market and begin heavy demand-creation spending or worse, believe it can accelerate customer adoption by “branding.” In a new market, there is no demand to create. Until the mainstream customers are identified and a plan to affect their behavior is agreed upon, spending infinite marketing dollars will not change sales revenue. In this Market Type, marketing is still a strategic function focused on helping Sales find the mainstream market, not on demand-creation activities.

The role of Business Development in a new market is to help Sales and Marketing bridge the perceptual gap between a company that is of interest only to earlyvangelists and one that makes sense for mainstream customers. Business Development does so by forming alliances and partnerships that are congruent with the “beachhead” markets being targeted by Sales. The goal is to make the company appear more palatable to mainstream customers by building the “whole product.” Table 6.4 summarizes department roles in a new market.

Table 6.4 Roles of Departments in a New Market

Department Roles in a Resegmented Market

A resegmented market requires strategies and departmental missions that combine the features of departments in existing and new markets. For this reason, departments in this type of company can sometimes feel and act schizophrenic. You start competing in an existing market where competition is fierce, with the goal of uniquely differentiating the product into a space where no one currently resides, but where you hope lots of customers will follow. At times Sales may act like it is in an existing marketing while Marketing plans new-market tactics. This confusion is par for the course, but requires close and frequent synchronization of missions and tactics.

The sales department in a resegmented market follows two tracks: selling to customers in an existing and very competitive environment (with a product that has fewer features than the competition) while simultaneously attempting to find new customers, as if in a new market. However, unlike a new market where the move to mainstream customers was predicated on chasm-crossing or tipping-point strategies (i.e., niche-at-a-time or epidemic), in a resegmented market Sales is counting on Marketing to use positioning and branding to “peel off” substantial numbers of existing customers by creating a differentiated segment. One of the risks is Sales becoming beguiled by the existing customers in the market you are attempting to resegment. Continuing low-level sales to address these customers is just a part of the sales strategy. Sales executives must remember the real goal is to change the perception of the current base of customers in order to create a new, much more valuable market segment—one where your product is the market leader.