CHAPTER 3

Customer Discovery

A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.

— Lao-tzu

IN 1994, STEVE POWELL HAD AN IDEA for a new type of home office device. Capitalizing on the new high-speed phone connection called ISDN, Steve envisioned creating the Swiss Army knife of home office devices. His box would offer fax, voicemail, intelligent call forwarding, email, video and phone all rolled into one. Initially Steve envisioned the market for his device would be the 11 million people with small offices or home offices (the SOHO market).

Steve's technical vision was compelling, and he raised $3 million in the first round of funding for his company, FastOffice. Like most technology startups, FastOffice was first headed by its creator, even though Steve was an engineer by training. A year after he got his first round of funding, he raised another $5 million at a higher valuation. In good Silicon Valley tradition, his team followed the canonical Product Development diagram, and in 18 months he had first customer ship of his product called Front Desk. There was just one small problem: Front Desk cost $1395, and at that price, customers were not exactly lining up at FastOffice's door. Steve's board had assumed that, as with all technology startups, first customer ship meant FastOffice was going to ramp up sales revenues the day the product was available. Six months after first customer ship, the company had missed its revenue plan and the investors were unhappy.

It was at about this time I met Steve and his management team. His venture firm asked me to come by and help Steve with his “positioning.” (Today when I hear that request I realize it's code for, “The product is shipping, but we're not selling any. Got any ideas?”) When I got a demo of Front Desk, my reaction was, “Wow, that's really an innovative device. I'd love to have one at home. How much is it?” When Steve told me it was $1400, my response was, “Gosh, I wouldn't buy one, but can I be a beta site?” I still remember Steve's heated reply: “That's the reaction everyone has. What's wrong? Why wouldn't you buy one?” The stark reality was FastOffice had built a Rolls Royce for people with Volkswagen budgets. Few—unfortunately, very few—small home businesses could afford it.

Steve and his team made one of the standard startup mistakes. They had developed a great product, but neglected to spend an equivalent amount of time developing the market. The home office market simply had no compelling need that made Front Desk a “must-have,” especially at a high price. FastOffice had a solution in search of a problem.

When Steve and his team realized individuals were simply not going to shell out $1400 for a “nice-to-have peripheral,” they needed a new strategy. Like all startups faced with this problem, FastOffice fired its VP of Sales and came up with a new sales and marketing strategy. Now, instead of selling to individuals who worked at home, the company would sell to Fortune 1000 corporations that had a “distributed workforce”— salespeople who had offices at home. The rationale was that a VP of Sales of a large corporation could justify spending $1400 on a high-value employee, and the “new” product, renamed HomeDesk, could make a single salesperson appear like a large corporate office.

While the new strategy sounded great on paper, it suffered from the same problem as the first: The product might be nice to have, but it did not solve a compelling problem. Vice Presidents of Sales at major corporations were not going to bed at night worrying about their remote offices. They were worrying about how to make their sales numbers.

What ensued was the startup version of the ritualized Japanese Noh play I mentioned in Chapter 1. Faced with the failure of Plan B, FastOffice fired the VP of Marketing and came up with yet another new strategy. The company was now on the startup Death Spiral: The executive staff changed with each new strategy. After the third strategy didn't work either, Steve was no longer CEO and the board brought in an experienced business executive.

What's interesting about the FastOffice story is that it's very common. Time and again, startups focus on first customer ship, and only after the product is out the door do they learn customers aren't behaving as expected. By the time the company realizes sales revenues won't meet expectations, it's already behind the proverbial eight ball. Is this the end of the story? No, we'll revisit FastOffice after we explain the Customer Discovery philosophy.

Like most startups, FastOffice knew how to build a product and how to measure progress toward the product ship date. What the company lacked was a set of early Customer Development goals that would have allowed it to measure its progress in understanding customers and finding a market for its product. These goals would have been achieved when FastOffice could answer four questions:

- Have we identified a problem a customer wants solved?

- Does our product solve these customer needs?

- If so, do we have a viable and profitable business model?

- Have we learned enough to go out and sell?

Answering these questions is the purpose of the first step in the Customer Development model, Customer Discovery. This chapter explains how to go about it.

The Customer Discovery Philosophy

Let me state the purpose of Customer Discovery a little more formally. A startup begins with a vision: a vision of a new product or service, how the product will reach its customers, and why lots of people will buy it. But most of what a startup's founders initially believe about their market and potential customers are just educated guesses. A startup is in reality a “faith-based enterprise” on day one. To turn the vision into reality and the faith into facts (and a profitable company), a startup must test those guesses, or hypotheses, and find out which are correct. So the general goal of Customer Discovery amounts to this: turning the founders’ initial hypotheses about their business model, market and customers into facts. And since the facts live outside the building, the primary activity is to get in front of customers, partners and suppliers. Only after the founders have performed this step will they know whether they have a valid vision or just a hallucination.

Sounds simple, doesn't it? Yet for anyone who has worked in established companies, the Customer Discovery process is disorienting. All the rules marketers learn about product management in large companies are turned upside down. It's instructive to enumerate all things you are not going to do:

- Understand the needs and wants of all customers

- Make a list of all the features customers want before they buy your product

- Hand product development a features list of the sum of all customer requests

- Hand product development a detailed marketing requirements document

- Run focus groups and test customers’ reactions to your product to see if they will buy

Instead, you are going to develop your product iteratively and incrementally for the few, not the many. Moreover, you're going to start building your product even before you know whether you have any customers for it.

For an experienced marketing or product management executive, these statements are not only disorienting and counterintuitive, they are heretical. Everything I say you are not supposed to do is what marketing and product management professionals have been trained to do well. Why aren't the needs of all potential customers important? What is it about a first product from a new company that's different from follow-on products in a large company? What is it about a startup's first customers that makes the rules so different?

Develop the Product for the Few, Not the Many

In a traditional product management and marketing process the goal is to develop a Marketing Requirements Document (MRD) for engineering. The MRD contains the sum of all the possible customer feature requests, prioritized in a collaborative effort among Marketing, Sales and Engineering. Marketing holds focus groups, analyzes sales data from the field, and looks at customer feature requests and complaints. This information leads to requested features that are added to the product specification, and the engineering team builds these features into the next release.

While this process is rational for an established company entering an existing market, it is folly for startups. Why? In established companies, the MRD process ensures engineering will build a product that appeals to an existing market. In this case the customers and their needs are known. In a startup, the first product is not designed to satisfy a mainstream customer. No startup can afford the engineering effort or the time to build a product with every feature a mainstream customer needs in its first release. The product would take years to get to market and be obsolete by the time it arrived. A successful startup solves this conundrum by focusing its development on building the product incrementally and iteratively and targets its early selling efforts on a very small group of early customers who have bought into the startup's vision. This small group of visionary customers will give the company the feedback necessary to add features into follow-on releases. Enthusiasts for products who spread the good news are often called evangelists. But we need a new word to describe visionary customers—those who will not only spread the good news about unfinished and untested products, but also buy them. I call them earlyvangelists. 1

Earlyvangelists: The Most Important Customers You'll Ever Know

Earlyvangelists are a special breed of customer willing to take a risk on your startup's product or service because they can envision its potential to solve a critical and immediate problem—and they have the budget to purchase it. Unfortunately, most customers don't fit this profile. Here's an example from the corporate world:

Imagine a bank with a line around the block on Fridays as customers wait an hour or more to get in and cash their paychecks. Now imagine you are one of the founders of a software company whose product could help the bank reduce customers’ waiting time to 10 minutes. You go into the bank and tell the president, “I have a product that can solve your problem.” If his response is “What problem?” you have a customer who does not recognize he has a pressing need you can help him with. There is no time in a startup's first two years of life that he will be a customer, and any feedback from him about product needs would be useless. Customers like these are traditional “late adopters” because they have a “latent need.”

Another response from the bank president could be, “Yes, we have a terrible problem. I feel very bad about it, and I hand out cups of water to our customers waiting in line on the hottest days of the year.” In this case, the bank president is the type of customer who recognizes he has a problem but hasn't been motivated to do anything more than paper over the symptoms. He may provide useful feedback about the type of problem he is experiencing, but more than likely he will not be first in line to buy a new product. Since these types of customers have an “active need,” you can probably sell to them later, when you can deliver a “mainstream” product, but not today.

If it's a good day, you may run into a bank president who says, “Yes, this is a heck of a problem. In fact, we're losing over $500,000 a year in business. I've been looking for a software solution that will cut down our check cashing and processing time by 70 percent. The software has to integrate with our bank's Oracle back end, and it has to cost less than $150,000. And I need it delivered in six months.” Now you're getting warm; this customer has “visualized the solution.” It would be even better if the president said, “I haven't seen a single software package that solves our problem, so I wrote a request for our IT department to develop one. They've cobbled together a solution, but it keeps crashing on my tellers and my CIO is having fits keeping it running.”

You're almost there: You've found a customer who has such a desperate problem he has had his own homegrown solution built out of piece parts.

Finally, imagine the bank president says, “Boy, if we could ever find a vendor who could solve this problem, we could spend the $500,000 I've budgeted with them.” (Truth be told, no real customer has ever said that. But we can dream, can't we?) At this point, you have found the ultimate customer for a startup selling to corporate customers. While consumer products usually don't have as many zeros in them, earlyvangelist consumers can be found by tracing out the same hierarchy of needs.

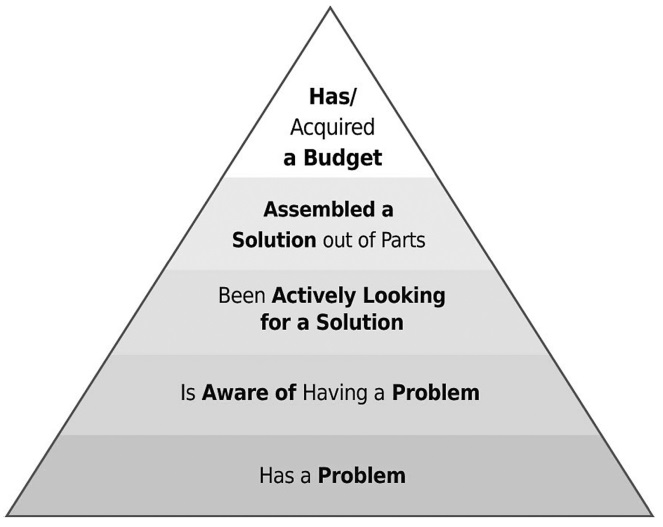

Earlyvangelists can be identified by these customer characteristics (see Figure 3.1):

- The customer has a problem

- The customer understands he or she has a problem

- The customer is actively searching for a solution and has a timetable for finding it

- The problem is painful enough the customer has cobbled together an interim solution

- The customer has committed, or can quickly acquire, budget dollars to solve the problem

Figure 3.1 Earlyvangelist Characteristics

You can think of these characteristics as making up a scale of customer pain. Characterizing customers’ pain on this scale is a critical part of Customer Discovery. My contention is that earlyvangelist customers will be found only at points 4 and 5: those who have already built a homegrown solution (whether in a company by building a software solution, or at home by taping together a fork, light bulb and vacuum cleaner) and have or can acquire a budget. These people are perfect earlyvangelist candidates. You will rely on them for feedback and for your first sales; they will tell others about your product and spread the word the vision is real. Moreover, when you meet them, you mentally include them on your list of expert customers to add to your advisory board (more about advisory boards in Chapter 4).

Start Development Based on the Vision

The idea that a startup builds its product for a small group of initial customers, and builds the product iteratively, rather than devising a specification with every possible feature for the mainstream, is radical. What follows is equally revolutionary.

On the day the company starts, there is very limited customer input to a product specification. The company doesn't know who its initial customers are (but it may think it knows) or what they will want as features. One alternative is to put Product Development on hold until the Customer Development team can find those customers. However, having a product you can demonstrate and iterate is helpful in moving the Customer Development process along. A more productive approach is to proceed with Product Development, with the feature list driven by the vision and experience of the company's founders.

Therefore, the Customer Development model has your founding team take the product as spec'd and search to see if there are customers—any customers—who will buy the product exactly as you have defined it. When you find those customers, you tailor the first release of the product so it satisfies their needs.

The shift in thinking is important. For the first product in a startup, your initial purpose in meeting customers is not to gather feature requests so you can change the product; it is to find customers for the product you are already building.

If, and only if, no customers can be found for the product as spec'd do you bring the features customers requested to the Product Development team. In the Customer Development model, then, feature request is by exception rather than rule. This eliminates the endless list of requests that often delay first customer ship and drive your Product Development team crazy.

If Product Development is simply going to start building the product without customer feedback, why talk to customers at all? Why not just build the product, ship it, and hope someone wants to buy it? The operative phrase is “start building the product.” The job of Customer Development is to get the company's customer knowledge to catch up to the pace of Product Development—and in the process, to guarantee there will be paying customers the day the product ships. An important side benefit is the credibility the Customer Development team accrues internally within your organization. Product Development will be interacting with a team that understands customer needs and desires. Product Development no longer will roll their eyes after every request for features or changes to the product, but instead understand they come from a deep understanding of customer needs.

As the Customer Development team discovers new insights about the needs of this core group of initial customers, it can provide valuable feedback to the Product Development group. As you'll see, these Customer Development/Product Development synchronization meetings ensure once key customer information becomes available it is integrated into the product's future development.

To sum up the Customer Discovery philosophy: In sharp contrast to the MRD approach of building a product for a wide group of customers, a successful startup's first release is designed to be “good enough only for our first paying customers.” The purpose of Customer Discovery is to identify those key visionary customers, understand their needs, and verify your product solves a problem they are willing to pay to have solved—or not. Meanwhile, you start development based on your initial vision, using your visionary customers to test whether that vision has a market. And you adjust your vision according to what you learn.

If FastOffice had understood this philosophy, it could have avoided several false starts. As it happens, there was a happy ending (at least for some later-stage investors), as the company survived and lived to play again. The new CEO worked with Steve Powell (who became the chief technical officer) to understand the true technical assets of the company. The new leadership terminated the sales and marketing staff and pared the company back to the core engineering team. What they discovered was their core asset was in the data communications technology that offered voiceover data communications lines. FastOffice discarded its products for the home, refocused, and became a major supplier of equipment to telecommunications carriers. The Customer Discovery process would have gotten the company there a lot sooner.

Overview Of The Customer Discovery Process

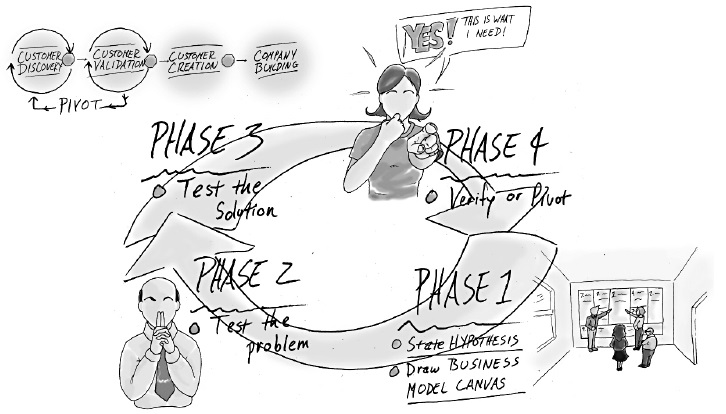

I've already touched on some of the elements of the philosophy behind this first step in the Customer Development model. Here's a quick overview of the entire process.

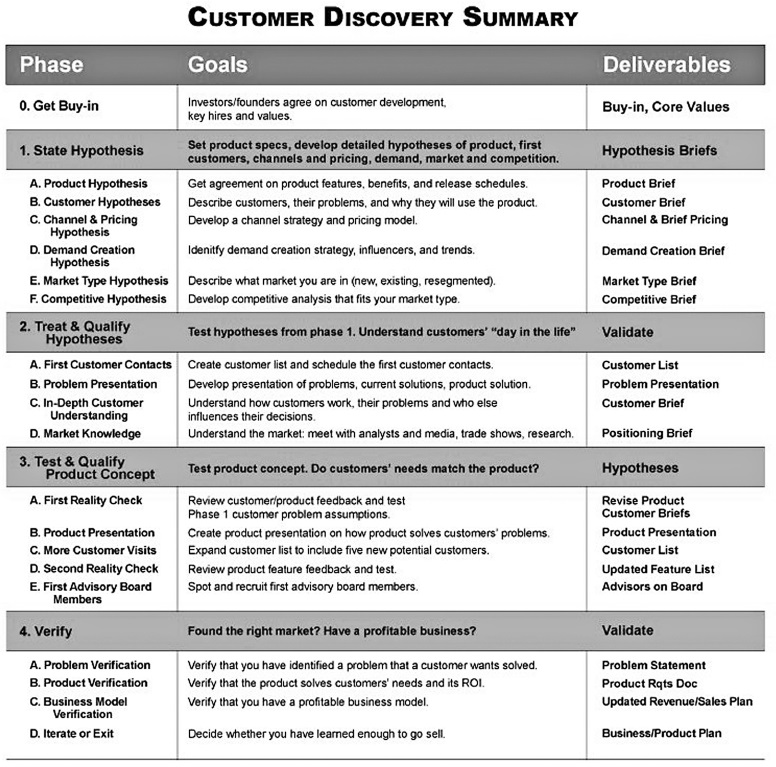

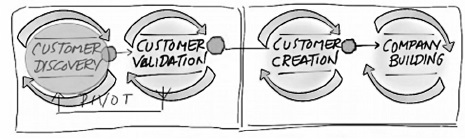

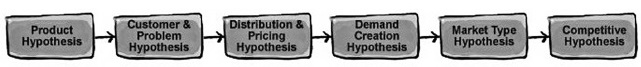

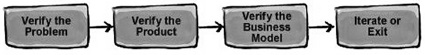

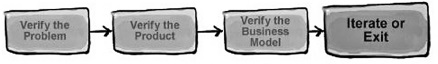

As with all the steps in Customer Development, I divide Customer Discovery into phases. Unlike subsequent steps, Customer Development has a “Phase 0.” Before you can get started, you need buy-in from your board and executive staff. Four more Customer Discovery phases follow (see Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2 Customer Discovery: Overview of the Process

Phase 1 is a rigorous process of writing a series of briefs that capture the hypotheses embodied in your company's vision and business model. These hypotheses are the assumptions about your product, customers, pricing, demand, market, and competition you will test in the remainder of this step.

In Phase 2 you qualify those assumptions by testing them in front of potential customers. At this point you want to do very little talking and a lot of listening. Your goal is to understand your customers and their problems, and arrive at a deep understanding of their business, workflow, organization, and product needs. You then return to your company, integrate all you learned, update Engineering with customer feedback, and jointly revise your product and customer briefs.

In Phase 3 you take your revised product concept and test its features in front of customers. The goal is not to sell the product but to validate the Phase 1 hypotheses by having customers say, “Yes, these features solve our problems.”

At the same time you've been testing the product features, you've been also testing a bigger idea: the validity of your entire business model. A valid business model consists of customers who place a high value on your solution, and find the solution you offer is (for a company) mission-critical, or (for a consumer) a “have-to-have” product (product/market fit.) In front of potential buyers, you test your pricing, channel strategy, sales process and sales cycle, and discover who is the economic buyer (the one with a budget). This is equally true for consumer products where a sale to a teenager might mean the economic buyer is the parent while the user is the child.

Finally, in Phase 4 you stop and verify you understand customers’ problems, that the product solves those problems, customers will pay for the product, and that the resulting revenue will result in a profitable business model. This phase culminates in the deliverables for the Customer Discovery step: a problem statement document, an expanded product requirement document, an updated sales and revenue plan, and a sound business and product plan. With your product features and business model validated, you decide whether you have learned enough to go out and try to sell your product to a few visionary customers or whether you need to go back to customers to learn some more. If, and only if, you are successful in this step do you proceed to Customer Validation.

That's Customer Discovery in a nutshell. The remainder of this chapter details each of the phases I have just described. The summary chart at the end of the chapter captures this step in detail along with the deliverables that tell you whether you've succeeded. But before you move into the details of each phase, you need to understand who is going to be doing the work of Customer Development. Who comprises the Customer Development team?

The Customer Development Team

The Customer Development process gives up traditional titles and replaces them with more functional ones. As a startup moves through the first two steps of the process, it has no Sales, Marketing or Business Development organizations or VPs. Instead, it relies on an entrepreneurial Customer Development team (see Appendix A for the rationale for the Customer Development team concept).

At first, this “team” may consist of the company's technical founder who moves out to talk with customers while five engineers write code (or build hardware, or design a new coffee cup, etc.). More often than not it includes a “head of Customer Development” who has a product marketing or product management background and is comfortable moving back and forth between customer and Product Development conversations. Later, as the startup moves into the Customer Validation step, the Customer Development team may grow to several people including a dedicated “sales closer” responsible for the logistics of getting early orders signed.

But whether it is a single individual or a team, Customer Development must have the authority to radically change the company's direction, product or mission and the creative, flexible mindset of an entrepreneur. To succeed in this process, the team members must possess:

- The ability to listen to customer objections and understand whether they are issues about the product, the presentation, the pricing, or something else (or the wrong type of customer)

- Experience moving between the customer and Product Development team

- The ability to embrace constant change

- The capacity to put themselves in their customers’ shoes, understand how they work and what problems they have

Complementing the Customer Development team is a startup's product execution team. While Customer Development is out of the building talking with customers, the product team is focused on creating the product. Often this team is headed by the product visionary who leads the development effort. As you will see, regular communication between Customer Development and product execution is critical.

Phase 0: Get Buy-In

Phase 0 consists of getting buy-in from all the key players on several fundamentals, including the Customer Development process itself, the company's mission, and its core values.

Customer Development as a separate process from Product Development is a new concept. Not all executives understand it. Not all board members understand it. Market Type is also a new concept and integral to several key Customer Development decisions. Consequently, before your company can embark on Customer Development as a formal process, you must get all the players educated. There must be agreement between investors and founders about the process, key hires, and values. You must make sure all the players—founders, key execs, and the board—understand the differences among Product Development, Customer Development and Market Type, and that they buy into the value of differentiating between them.

The Product Development process emphasizes execution. The Customer Development process emphasizes learning, discovery, failure, iterations and pivots. For this reason you want to ensure there is enough funding for two to three passes through the Customer Discovery and Customer Validation steps. This is a discussion the founding team needs to have with its board early on. Does the board believe Customer Development is iterative? Does the board believe it is necessary and worth spending time on?

Unique to the process is the commitment of the Product Development team to spend at least 15% of its time outside the building talking to customers. You need to review these organizational differences with your entire startup team and make sure everyone is on board.

You also want to articulate in writing both the business and product vision of why you started the company. Called a mission statement, at this point in your company's life this document is nothing more than “what we were thinking when we were out raising money.” It can be no more complicated than the two paragraphs used in the business plan to describe your product and the market. Write these down and post them on the wall. When the company is confused about what product to build or what market you wanted to serve, refer to the mission statement. This is called mission-oriented leadership. In times of crisis or confusion, understanding why the company exists and what its goals are will provide a welcome beacon of clarity.

Over time, a company's mission statement changes. It may change subtly over a period of months, or dramatically over a week, but a wise management team will not change it with the latest market or product fad.

Finally, next to the mission statement post the founding team's core values. Unlike mission statements, core values are not about markets or products. They are a set of fundamental beliefs about what the company stands for that can endure the test of time: the ethical, moral, and emotional rocks on which the company is built. A good example of a long-lasting set of core values is the Ten Commandments. It's not too often that you hear someone say, “Hey, maybe we should get rid of the second commandment.” More than 4,000 years after they were committed to paper—well, tablets—these values are still the rock on which Judeo-Christian ethics rest.

To take an example closer to our purpose, the founding team of a pharmaceutical company articulated a powerful core value: “First and foremost, we believe in making drugs that help people.” The founders could have said, “We believe in profits first and at all costs,” and that, too, would be a core value. Neither is right or wrong, so long as it truly expresses what the company believes in.

When the company's mission or direction is uncertain, the core values can be referenced for direction and guidance. For core values to be of use, a maximum of three to five should be articulated. 2

Phase 1: State Your Hypotheses

Once the company has bought into Customer Development as a process in Phase 0, the next phase of Customer Discovery is to write down all of your company's initial assumptions, or hypotheses. Getting your hypotheses down on paper is essential because you will refer to them, test them, and update them during the entire Customer Development process. Your written summary of these hypotheses will take the form of a one-or two-page brief about each of the following areas:

- Product

- Customer and their problem

- Channel and pricing

- Demand creation

- Market Type

- Competition

Initially, you may lack the information to complete these hypotheses. In fact some of your briefs may be shockingly empty. Not to worry. These briefs will serve as an outline to guide you. During the course of Customer Discovery, you will return to these briefs often, to fill in the blanks and modify your original hypotheses with new facts you have learned as you talk to more and more customers. In this first phase, you want to get down what you know (or assume you know) on paper and create a template to record the new information you will discover.

A. State Your Hypotheses: The Product

Product hypotheses consist of the founding team's initial guesses about the product and its development. Something like these were part of the company's original business plan.

First Product Development/Customer Development Synchronizaton Meeting

Most of the product brief is produced by the Product Development team. This is one of the few times you are going to ask the head of product execution and his or her partner, the keeper of the technical vision, to engage in a paper exercise. Getting your product hypotheses down on paper and turning them into a product brief, agreed to by all executives, is necessary for the Customer Development team to begin its job.

The product brief covers these six areas:

- Product features

- Product benefits

- Intellectual property

- Dependency analysis

- Product delivery schedule

- Total cost of ownership/adoption

Here is a short description of what should be covered in each area.

Product Hypotheses: Product Features

The product features list is a one-page document consisting of one-or two-sentence summaries of the top 10 (or fewer) features of the product. (If there is some ambiguity in describing a particular feature, include a reference to a more detailed engineering document.) The features list is Product Development's written contract with the rest of the company. The biggest challenge will be deciding what features will ship in what order. We'll address how you prioritize first customer ship features a bit later.

Product Hypotheses: Product Benefits

The benefits list succinctly describes what benefits the product will deliver to customers. (Something new? Something better? Faster? Cheaper?) In large companies, it's normal for Marketing to describe the product benefits. The Customer Development model, however, recognizes that Marketing doesn't know anything about customers yet. In a startup Product Development has all kinds of customer “facts.” Use this meeting to flush these out. At this point, the marketing people must bite their tongues and listen to the Product Development group's assumptions about how the features will benefit customers. These engineering-driven benefits represent hypotheses you will test against real customer opinions.

Product Hypotheses: Intellectual Property

In the next part of the brief, the product team provides a concise summary of assumptions and questions about intellectual property (IP). Are you inventing anything unique? Is any of your IP patentable? Do you have trade secrets to protect? Have you checked to see whether you infringe on others’ IP? Do you need to license others’ patents? Although most development groups tend to look at patents as a pain in the rear, and management believes the expense of securing patents is prohibitive, taking an active patent position is prudent. As your company gets larger, other companies may believe you infringe on their patents, so having intellectual property to horse-trade can come in handy. More importantly, if you own critical patents in a nascent industry, they can become a major financial asset of the company.

Product Hypotheses: Dependency Analysis

A dependency analysis is simpler than it sounds. The Product and Customer Development teams jointly prepare a one-page document that says, “For us to be successful (that is, to sell our product in volume), here's what has to happen that is out of our control.” Things out of a company's control can include other technology infrastructure that needs to emerge (all cell phones become Web-enabled, fiber optics are in every home, electric cars are selling in volume), changes in consumers’ lifestyles or buying behavior, new laws, changes in economic conditions, and so on. For each factor, the dependency analysis specifies what needs to happen (let's say the widespread adoption of telepathy), when it needs to happen (telepathy must be common among consumers under age 25 by 2010), and what it means for you if it doesn't happen (your product needs to use the Internet instead). Also write down how you can measure whether each external change is happening when you need it to (college kids can read minds by 2020).

Product Hypotheses: Product Delivery Schedule

In the product delivery schedule, you ask the product team to specify not only the date of the first release (the minimum feature set), but the delivery and feature schedule for follow-on products or multiple releases of the product as far out as the team can see (up to 18 months). In startups, this request usually elicits a response like, “How can I come up with a date for future releases when we barely know when our first release will be?” That's a good question, so you'll need to make clear to the product team why you need their cooperation and best estimates. These are important because the Customer Development team will be out trying to convince a small group of early customers to buy based on the product spec long before you can physically deliver the product. To do so they will have to paint a picture for customers of what the product will ultimately look like several releases into the future. It's because these customers are buying into your total vision that they will give you money for an incomplete, buggy, barely functional first product.

Asking for dates in this phase may result in an anxious Product Development team. Reassure them this first pass at a schedule is not set in stone. It will be used throughout Customer Discovery to test customer reaction but not to make customer commitments. At the beginning of the next step, Customer Validation, the teams will revisit the product delivery schedule and commit to firm dates that can be turned into contractual obligations.

Product Hypotheses: Total Cost Of Ownership/Adoption

The total cost of ownership (TCO) adoption analysis estimates the total cost to customers of buying and using your product. For business products, do customers need to buy a new computer to run your software? Do they need training to use the product? What other physical or organizational changes need to happen? What will be the cost of deployment across a whole company? For consumer products, it measures the cost of “adopting” the product to fit their needs. Do customers need to change their lifestyle? Do they need to change any part of their purchasing or usage behavior? Do they need to throw away or make obsolete something they use today? While the Customer Development team prepares this estimate, the Product Development team should provide feedback about whether the estimates are realistic.

When all of the six hypotheses about the product are written down, the company has a brief that describes the product in some detail. Paste your brief to the wall. Soon it will be joined by a few more. Soon after, you will be in front of customers testing these assumptions.

B. State Your Hypotheses: Customer Hypotheses

The process of assembling the customer briefs is the same as for the product brief, except this time the Customer Development team is writing down its initial assumptions. These assumptions cover two key areas: who the customers are (the customer hypothesis) and what problems they have (the problem hypothesis). In the course of Customer Discovery, you'll flesh out these assumptions with additional information:

- Types of customers

- Customer problems

- A day in the life of your customers

- Organizational map and customer influence map

- ROI (return on investment) justification

- Minimum feature set

Again, let's consider each part of the customer and problem briefs in turn.

Customer Hypotheses: Types of Customers

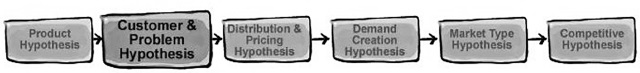

If you've ever sold a product, whether it's to a consumer buying a stick of gum or a company buying a million-dollar telecommunications system, you've probably discovered every sale has a set of decision-makers who get their fingers into the process. So the first question to ask is, “Are there different types of customers we should approach when we sell our product?” Whether you're selling process control software into a large corporation or a new type of home vacuuming device, chances are there are a number of people in a number of categories whose needs you must satisfy to sell the product. During Customer Discovery you will spend time understanding these needs. Later, when you are ready to develop your first “sales roadmap” in the Customer Validation step, knowing all the players in detail will be essential. Right now, it's sufficient to realize the word “customer” is more complicated than a single individual. Some of the customer types I have encountered include (see Figure 3.3):

Figure 3.3 Customer Types

These are the day-to-day users of the product, the ones who will push the buttons, touch the product, play with it, use it, love it and hate it. You need a deep understanding of the end users’ needs, but it's important to realize in some cases the end user may have the least influence in the sales process. This is typically true in complex corporate sales where an entire food chain of decision-makers affects the purchasing decision. However, it's equally true in a consumer sale. For example, children are a large consumer market and the users of many products, but their parents are the buyers.

Next up the sales chain are all the people who think they have a stake in a product coming into their company or home. This category could include the key techno-whiz in IT or the 10-year-old whose likes and dislikes influence the family's choices of consumer products.

These people influence product purchase decisions. They differ from the influencers in that they can make or break a sale. A recommender could be a department head saying any new PCs should come from Dell or the spouse who has a particularly strong brand preference.

Further up the decision chain is the economic buyer, the one who has the budget for the purchase and must approve the expenditure. (Don't you bet you are going to want to know who that is?) In a consumer purchase it can be a teen with a weekly music budget or a spouse with a vacation budget.

The decision-maker could be the economic buyer, but it could be someone else even higher in the decision-making hierarchy. The decision-maker is the person who has the ultimate say about a product purchase regardless of the other users, influencers, recommenders and economic buyers. Depending on your product, the decision-maker could be a suburban soccer mom/dad or a Fortune 500 CEO. It is up to you to discover the ultimate purchase decision-maker and understand how all these other customer types influence his or her final decision.

In addition to all these parties to the sale (and isn't it amazing with a process like this, anything gets sold?), one more group must be mentioned. You won't be looking for them, but they will see you coming. I call this group the saboteurs. In every large company, for example, there are individuals and organizations that are wedded to the status quo. If your product threatens a department's stability, headcount, or budget, don't expect this group to welcome you with open arms. Therefore you need to be able to predict who might be most threatened by your product, understand their influence in the organization, and ultimately put together a sales strategy that at worst neutralizes their influence and at best turns them into allies. Don't think saboteurs occur just in large corporations. For a consumer product, it may be a member of the family who has gotten comfortable with the old car and is uncomfortable about driving something new and different.

The first step in formulating your customer brief is to write down and diagram who you think will be your day-to-day users, influencers, recommenders, economic buyer, and decision-maker, including, in the case of sales to companies, their titles and where in the organization they are found. It's also worth noting if you think the economic buyer has a current budget for your product or one like it, or whether you will have to persuade the customer to get funds to buy your product.

Given you haven't been out talking to customers yet, you may have a lot of empty space in this part of your brief. That's fine. It just reminds you how much you need to find out.

Of course, not every product has so complicated a purchase hierarchy, but the sale of nearly every product involves multiple people. If it's a consumer product, these rules still apply. It's just that the influencers, recommenders, and so on are likely to have more familiar titles like “mom,” “dad,” and “kids.”

Customer Hypotheses: Types of Customers for Consumer Products

Some consumer products (clothing, fashion, entertainment products, etc.) don't address a “problem,” or need. In fact, U.S. consumers spend over 40 percent of their income on discretionary purchases, i.e. luxuries. How to sell to consumers starts with identifying customer types as described above. What's different is recognizing that since a real problem or need does not exist, for consumers to purchase a luxury, they must give themselves a justification for the purchase. In the Customer Creation step your marketing programs will promise consumers their unneeded spending will be worth it. It suffices in this phase to identify the consumer “customer types” and have a hypothesis about their emotional wants and desires. Describe how you can convince these customers that your product can deliver an emotional payoff.

Customer Hypotheses: Customer Problems

Next, you want to understand what problem the customer has. The reason is simple: It's much easier to sell when you can build the story about your product's features and benefits around a solution to a problem you know the customer already has. Then you look less like a crass entrepreneur and more like someone who cares coming in with a potentially valuable solution.

Understanding your customers’ problems involves understanding their pain—that is, how customers experience the problem, and why (and how much) it matters to them. Let's go back to the problem of the long line of people trying to cash their paychecks at the bank. It's obvious there's a problem, but let's try to think about the problem from the bank's point of view (the bank being your customer). What is the biggest pain bank employees experience? The answer is different for different people in the bank. To the bank president, the pain might be the bank lost $500,000 last year in customer deposits when frustrated customers took their business elsewhere. To the branch manager, the biggest pain is her inability to cash customer paychecks efficiently. And to the bank tellers, the biggest pain is dealing with customers who are frustrated and angry by the time they get to the teller window.

Now imagine you asked the employees in this bank, “If you could wave a magic wand and change anything at all, what would it be?” You can guess the bank president would ask for a solution that could be put in place quickly and cost less than the bank is losing in customer deposits. The branch manager would want a way to process checks faster on paydays that would work with the software already in place and not force a change in the bank's day-to-day processes. The tellers would want customers who don't growl at them and please, no new buttons, terminals, and systems.

It's not much of a stretch to imagine running this same exercise for a consumer product. This time instead of a bank president and tellers, imagine the prototypical nuclear family discussing buying a car. Each family member likely has their own view of their transportation needs. You might naively assume the breadwinner with the largest paycheck makes the decision. But as with the different customer problems at the bank, 21st-century consumer purchases are never that simple.

These examples show that you need to summarize the customer‘s problem, and the organizational impact of the problem in terms of the different types of pain it causes at various levels of the company/family/consumer. Finally, writing down the answer to “If they could wave a magic wand and change anything at all, what would it be?” gives you a tremendous leg up on how to present your new product.

Earlier in this chapter, I discussed five levels of problem awareness customers might have. In this customer problem brief, you use a simple “problem recognition scale” for each type of customer (user, influencer, recommender, economic buyer, decision-maker). As you learn more you can begin to categorize your customers as having:

- A latent need (the customers have a problem or they have a problem and understand they have a problem)

- An active need (the customers recognize a problem—they are in pain—and are actively searching for a solution, but they haven't done any serious work to solve the problem)

- A vision (the customers have an idea what a solution to the problem would look like, may even have cobbled together a homegrown solution, and, in the best case, are prepared to pay for a better solution)

Now that you are firmly ensconced in thinking through your customers’ problems, look at the problem from one other perspective: Are you solving a mission-critical company problem or satisfying a must-have consumer need? Is your product have-to-have? Is it nice-to-have? In our bank example, long lines on pay day costing the bank $500,000 a year might be a mission-critical issue if the bank's profits are only $5,000,000 a year, or if the problem is occurring at every branch in the country, so the number of customers lost is multiplied across hundreds of branches. But if you're talking about a problem at only one branch of a multinational banking organization, it's not mission-critical.

The same is true for our consumer example. Does the family already have two cars in fine operating condition? Or has one broken down and the other is on its last legs? While the former is an impulse purchase, the latter is a “must-have” need.

As I suggested earlier, one test of a have-to-have product is that the customers have built or have been trying to build a solution themselves. Bad news? No, it's the best news a startup could find. You have uncovered a mission-critical problem and customers with a vision of a solution. Wow. Now all you need to do is convince them that if they build it themselves they are in the software development and maintenance business, and that's what your company does for a living.

Customer Hypotheses: A Day in your Customer's Life

One of the most satisfying exercises for a true entrepreneur executing Customer Development is to discover how a customer “works.” The next part of the customer problem brief expresses this understanding in the form of “a day in the life of a customer.”

In the case of businesses, this step requires a deep understanding of a target company on many levels. Let's continue with our banking example. How a bank works is not something you will discover from cashing a check. You want to know how the world looks from a banker's perspective. How do the potential end users of the product (the tellers) spend their days? What products do they use? How much time do they spend using them? How would life change for these users after they had your product? Unless you've been a bank teller, these questions should leave you feeling somewhat at a loss. But how are you going to sell a product to a bank to solve tellers’ problems if you don't know how they work?

Now run this exercise again, this time from the perspective of branch managers. How do they spend their day? How would your new product affect them? Run it again, this time thinking about the bank president. What on earth does the bank president do? How will your product affect her? And if you are installing a product that connects to other software the bank has, you are going to have to deal with the IT organization. How do the IT people spend their day? What other software do they run? How are their existing systems configured? Who are their preferred vendors? Are they standing at the door waiting to welcome yet another new company and product with confetti and champagne?

Finally, what do you know about trends in the banking industry? Is there a banking industry software consortium? Are there banking software trade shows? Industry analysts? Unless you have come from your target industry, this part of your customer problem brief may include little more than lots of question marks. That's OK. In Customer Development, the answers turn out to be easy; asking the right questions is difficult. You will go out and talk to customers with the goal of filling in all the blank spots on the customer/problem brief.

For a consumer product, the same exercise applies. How do consumers solve their problems today? How would they solve their problems having your product? Would they be happier? Smarter? Feel better? Do you understand how and what will motivate these customers to buy?

Your final exam doesn't happen until you come back to the company and, in meetings with the Product Development team and your peers, draw a vivid and specific picture of a day in the life of your customer.

Customer Hypotheses: Organizational Map and Customer Influence Map

Having now a deeper understanding of the day in the life of a customer, you realize that except in rare cases most customers do not work by themselves. They interact with other people. In enterprise sales it will be other people in their company, and in a sale to a consumer their interaction is with their friends and/or family. This part of the brief has you first listing all the people you can think of who could influence a customer's buying decisions. Your goal is to build a tentative organizational map showing all the potential influencers who surround the user of the product. If it's a large company the diagram may be complex and have lots of unknowns right now. If it's a sale to a consumer, the diagram might appear to be deceptively simple but with the same thought—it's clear consumers have a web of influencers as well. Over time this map will become the starting point for the sales roadmap described in detail in the next chapter.

Once you have the organizational map, the next step is to understand the relationships among the recommenders, influencers, economic buyers, and saboteurs. How do you think a sale will be made? Who must be convinced (and in what order) for you and your company to make a sale? This is the beginning of your customer influence map.

Customer Hypotheses: ROI (Return On Investment) Justification

Now that you know everything about how a customer works, you're done, right? Not yet. For purchases both corporate and consumer, customers need to feel the purchase was “worth it,” that they got “a good deal.” For a company this is called return on investment, or ROI. (For a consumer this can be “status” or some other justification of their wants and desires.) ROI represents customers’ expectation from their investment measured against goals such as time, money, or resources as well as status for consumers.

In our banking example, the ROI justification is relatively easy. From listening to your customer, you figure the bank is losing $500,000 in gross customer revenue per year. The profit on every customer is 4 percent. Therefore, at every branch $20,000 in profit leaves with those lost customers. (When you first construct your brief, numbers like these are just your guesses. As you get customer feedback, you can plug in more accurate amounts.) Now suppose you've found out 100 other branches have the same problem. That's a $50 million problem and $2 million in profit gone. Your software to solve this problem costs $200,000, plus $50,000 per year in maintenance fees. Integration and installation will probably take 18 person-months—say, another $250,000 in customer costs. The customers will need to dedicate a full-time IT professional to maintain the system; you budget another $150,000 for this. Finally, training all the tellers in 100 branches will cost another $250,000.

Let's round up all the direct costs (money the bank will pay you) to $500,000 and the indirect costs (money the bank spends on its own staff) to $400,000. As you can see from Figure 3.4, the bank would spend $900,000 for your solution. That seems like a lot of money just to make customer lines shorter. But because you understand how the bank works, you know installing your product will save the bank over $2,000,000 a year. Your product will pay for itself in less than six months, and every year the bank will have an extra $1.85 million in profit. That's an amazing return on investment.

Figure 3.4 ROI Calculation for ABC Bank

Imagine having a slide showing this type of calculation in your customer presentation!

Most startups are unprepared to deal with the customer's ROI. At best, they ignore it, and at worst, they confuse it with the price of the product. (ROI, as you'll see, involves a lot more than price.) Now, most customers never directly ask a startup about ROI because they assume no outside vendor would be familiar enough with their internal operations to develop valid ROI metrics. Suppose you were the exception. Imagine you were able to help customers justify the ROI for your product. That would be pretty powerful, wouldn't it? Yep. And that's why you include the customer's ROI as part of the customer problem brief. To do that you have to decide what to measure in calculating ROI. Increased revenues? Cost reduction, or cost containment? Displaced costs? Avoided costs? Intangibles?

Your earlyvangelists will end up using your ROI metrics to help sell your product inside their own company! It's with that end in mind that you include an ROI justification in the customer/problem brief. Early on, it's a placeholder for the powerful tool you'll develop as you learn more about your customers.

Customer Hypotheses: Minimum Feature Set

The last part of your customer/problem brief is one the Product Development team will be surprised to see. You want to understand the smallest feature set customers will pay for in the first release.

The minimum feature set is the inverse of what most sales and marketing groups ask of their development teams. Usually the cry is for more features, typically based on “here's what I heard from the last customer I visited.” In the Customer Development model, however, the premise is that a very small group of early visionary customers will guide your follow-on features. So your mantra becomes, “Less is more, to get an earlier first release.” Rather than asking customers explicitly about feature X, Y or Z, one approach to defining the minimum features set is to ask, “What is the smallest or least complicated problem the customer will pay us to solve?”

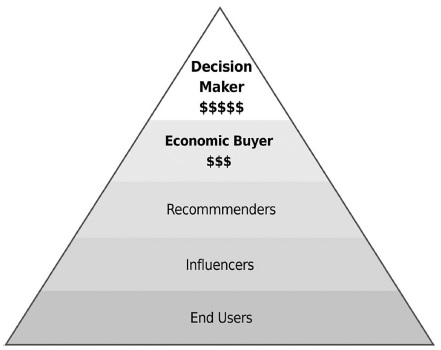

C. State Your Hypotheses: Channel and Pricing Hypotheses

Your channel/pricing brief puts your first stake in the ground describing what distribution channel you intend to use to reach customers (direct, online, telemarketing, reps, retail, etc.), as well as your first guess at product pricing. As you'll see, decisions about pricing and distribution channels are interrelated.

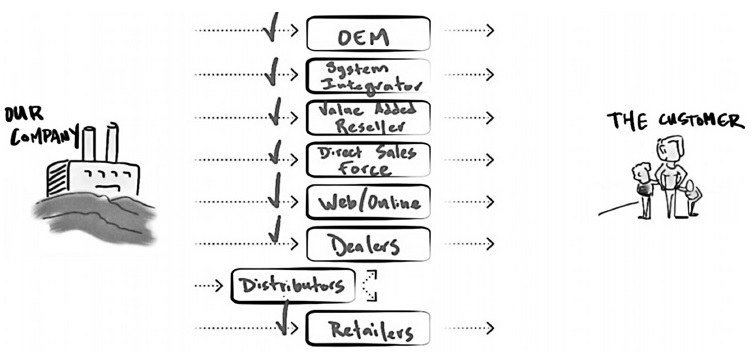

Let's take distribution channels first. Distribution channels make up the route a product follows from its origin (your company) to the last consumer. If you are selling directly to customers, you may need additional partners to help you install or deliver a complete product (system integrators, third-party software.) If you are selling indirectly, through middlemen, you need channel partners to physically distribute the product. Figure 3.5 illustrates how this process works. At the far right are the customers who have a problem that can be solved by your company's product and/or services.

Figure 3.5 Distribution Channel Alternatives

At the top of the figure, original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and system integrators derive a relatively small percentage of their total revenue from the sale of your product, and a greater percentage from their value-add in business process and unique solutions to customer problems. At the bottom of the diagram, retailers and mass merchants derive most of their revenue from the sale of your product. The primary value of retailers and mass merchants is providing products that are accessible and available off-the-shelf. Between these two extremes are a variety of sales channels that provide a combination of products and services. All but one are “indirect channels.” That means someone other than your company owns the relationship with the customer. The exception is a direct sales channel, where you hire and staff the organization that sells directly to your customer.

A startup picks a sales channel with three criteria in mind: (1) Does the channel add value to the sales process? (2) What are the price and the complexity of the product? And (3) Are there established customer buying habits/practices? In a “value-added” channel the channel may provide one-on-one sales contacts, special services such as installation, repair or integration. In contrast, a “shrink-wrapped” product is often purchased directly from catalogs, online or from store floor displays. Typically, professional products are sold for higher prices than shrink-wrap products; hence channels servicing shrink-wrap products (such as retailers and mass merchants) can operate at lower margin points.

In your channel/pricing brief, you spell out your initial hypotheses about how your product will reach customers. In the example of the $200,000 banking software described earlier, the first question you must answer is, how will customers initially buy from you? Directly from your company? From a distributor? Through a partner? In a retail store? Via mail order? Via the Internet?

The answer depends on a number of factors, beginning with the product's projected price, its complexity and the established customer buying preferences.

There are a few questions you can ask yourself to help understand what pricing best fits your product. If there are products somewhat like yours, how much do customers spend for them today? If users need a product like yours, how much do they pay to do the same thing today? In the case of your new banking software, suppose you discovered banks were already buying products with fewer features for over $500,000. This would give you a solid data point that your $200,000 price would be well accepted. In the case where there is no product like yours, ask how customers would solve their problem using piece-part solutions from a variety of vendors. How much would the sum of those multiple products cost?

Two final thoughts about pricing. The first is the notion of “lifetime value” of a customer; how much can you sell to a customer not just from the first sale, but over the life of the sales relationship? For example, having decided to sell your banking software direct, your first thought might be to sell the bank a single product, then charge annual maintenance fees. However, once you thought about all the work it would take to sell a single bank, it might dawn on you that you could offer this bank a suite of products. This would mean you could go back and sell a new product year after year (or as long as the new products met the needs of the bank). By thinking dramatically about the lifetime value of your customers, you can affect your product strategy.

The second idea is one I use with customers all the time in this phase. I ask them, “If the product were free, how many would you actually deploy or use?” The goal is to take pricing away as an issue and see whether the product itself gets customers excited. If it does, I follow up with: “OK, it's not free. In fact, imagine I charged you $1 million. Would you buy it?” While this may sound like a facetious dialog, I use it all the time. Why? Because more than half the time customers will say something like, “Steve, you're out of your mind. This product isn't worth more than $250,000.” I've just gotten customers to tell me how much they are willing to pay. Wow.

D. State Your Hypotheses: Demand Creation Hypotheses

Some day you will have to “create demand” to reach these customers and “get” them into your sales channel. Use the opportunity of talking to them to find out how they learn about new companies and new products. This brief reflects your hypotheses about how customers will hear about your company and product once you are ready to sell.

In the course of Customer Discovery, you'll flesh out these assumptions with additional information on creating customer demand and identifying influencers.

Demand Creation Hypotheses: Creating Customer Demand

In a perfect world customers would know telepathically how wonderful your product is, drive, fly or walk to your company, and line up to give you money. Unfortunately it doesn't work that way. You need to create “demand” for your product. Once you create this demand you need to drive those customers into the sales channel that carries your product. In this brief you will start to answer the questions: How will you create demand to drive them into the channel you have chosen? Through advertising? Public relations? Retail store promotions? Spam? Website? Word of mouth? Seminars? Telemarketing? Partners? This is somewhat of a trick question, as each distribution channel has a natural cost of demand creation. That means the further away from a direct sales force your channel is, the more expensive your demand creation activities are. Why? By their very appearance on a customer's doorstep a direct sales force is not only selling your product, they are implicitly marketing and advertising it. At the other extreme, a retail channel (Wal-Mart, a grocery store shelf or a website) is nothing more than a shelf on which the product passively sits. The product is not going to leap off the shelf and explain itself to customers. They need to have been influenced via advertising or public relations or some other means, before they will come in to buy.

You also need to understand how your customers hear about new companies and products. Do they go to trade shows? Do others in their company go? What magazines do they read? Which ones do they trust? What do their bosses read? Who are the best salespeople they know? Who would they hire to call on them?

Demand Creation Hypotheses: Influencers

At times the most powerful pressure on a customer's buying decision may not be something your company did directly. It may be something someone who did not work for you said or did not say. In every market or industry there is a select group of individuals who pioneer the trends, style, and opinions. They may be paid pundits in market research firms. They may be kids who wear the latest fashions. In this brief you need to identify the influencers who can affect your customer's opinions. Your brief includes the list of outside influencers: analysts, bloggers, journalists, and so on. Who are the visionaries in social media or the blogger, press/analyst community customers read and listen to? That they respect? This list will also become your roadmap for assembling an advisory board as well as targeting key industry analysts and press contacts in the Customer Validation step.

E. State Your Hypotheses: Market Type Hypotheses

In Chapter 2, I introduced the concept of Market Type. Startup companies generally enter one of four Market Types and ultimately your company will need to choose one of these. However, unlike decisions about product features, the Market Type is a “late-binding-decision.” This means you can defer this final decision until Customer Creation but you still need a working hypothesis. In the next two chapters, I'll come back to the Market Type your company is in and help you to refine and deepen your analysis after you have learned more about your customers and your market.

However, because the consequences of the wrong choice are severe, you would be wise to develop initial Market Type hypotheses you can test as you move through the Customer Development phase. To do this, the Customer Development team should record its initial Market Type and brainstorm with the Product Development team. In this brief, you will seek a provisional answer to a single question: Is your company entering an existing market, resegmenting an existing market or creating a new market?

For some startups the choice is pretty clear. If you are entering a market where you are in a “clone business,” such as computers or PDAs, the choice is already made for you: you are in an existing market. If you have invented a radically new class of product no one has seen before, you are likely in a new market. However, most companies have the luxury to choose which Market Type to use. So how to choose? A few simple questions begin the process:

- Is there an established and well-defined market with large numbers of customers?

- Does your product have better “something” (performance, features, service) than the existing competitors? If so, you are in an existing market.

- Is there an established and well-defined market with large numbers of customers and your product costs less than the incumbents’? You are in a resegmented market.

- Is there an established and well-defined market with large numbers of customers where your product can be uniquely differentiated from the existing incumbents? You are also in a resegmented market.

If there is no established and well-defined market, with no existing competitors you are creating a new market. Don't worry if you waver among the four Market Type choices. As you start talking to customers, they will have lots of opinions about where you fit. For now, go through each of the market types and pick the one that best fits your vision today. Table 3.1, which you saw in Chapter 2, is a reminder of the trade-offs.

Table 3.1 Market Type

| Existing Market | Resegmented Market | New Market | |

| Customers | Existing | Existing | New/New usage |

| Customer Needs | Performance |

|

Simplicity & convenience |

| Performance | Better/faster |

|

Low in “traditional attributes”, improved by new customer metrics |

| Competition | Existing incumbents | Existing incumbents | Non-consumption/other startups |

| Risks | Existing incumbents |

|

Market adoption |

Market Type Hypotheses: Entering An Existing Market

If you believe your company and product fit in an existing market, you need to understand how your product outperforms those of your competitors. Positioning your product against the slew of existing competitors is accomplished by adroitly picking the correct product features where you are better. Summarize your thinking in a brief. If you believe you are entering an existing market, good questions to address in your brief include:

- Who are the competitors and who is driving the market?

- What is the market share of each of the competitors?

- What are the total marketing and sales dollars the market share leaders will be spending to compete with you?

- Do you understand the cost of entry against incumbent competitors? (See the Customer Creation step in Chapter 5)

- Since you are going to compete on performance, what performance attributes have customers told you are important? How do competitors define performance?

- What percentage of this market do you want to capture in years one through three?

- How do the competitors define the market?

- Are there existing standards? If so, whose agenda is driving the standards?

- Do you want your company to embrace these standards, extend them, or replace them? (If you want to extend or replace them, you may be trying to resegment a market. However, if you truly are entering an existing market, then you will want to ensure you also fill out the competitive brief discussed in Step F. It will help shape your positioning further.)

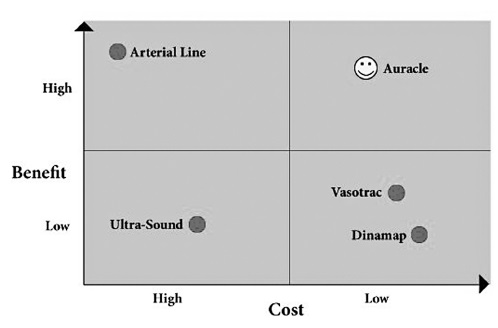

One way to capture your thinking on an existing Market Type is to construct a competitive diagram. Usually a company picks two or more key product attributes and attacks competitors along axes corresponding to these attributes, such as feature/technology axis, price/performance axis, and channel/margin axis. The competitive diagram used in an existing market typically looks like Figure 3.6, with each of the axes chosen to emphasize the best competitive advantage about the product.

Figure 3.6 Example of a Competitive Diagram

Picking the correct axes for the basis of competition is critical. The idea is that in entering an existing market, positioning is all about the product and specifically the value customers place on its new features.

Market Type Hypotheses: Resegmenting An Existing Market

An alternative to going head to head with the market leaders in an existing market may be to resegment an existing market. Here your positioning will rest on either a) the claim of being the “low-cost provider” or b) finding a niche via positioning (some feature of your product or service redefines the existing market so you have a unique competitive advantage).

If you believe you are resegmenting an existing market, good questions to address in this brief include:

- What existing markets are your customers coming from?

- What are the unique characteristics of those customers?

- What compelling needs of those customers are unmet by existing suppliers?

- What compelling features of your product will get customers of existing companies to abandon their current supplier?

- Why couldn't existing companies offer the same thing?

- How long will it take you to educate potential customers and grow a market of sufficient size? What size is that?

- How will you educate the market? How will you create demand?

- Given no customers yet exist in your new segment, what are realistic year one-through-three sales forecasts?

For this type of startup, you need to draw both the competitive diagram (because, unlike startups in a wholly new market, you have competitors) and the market map (because you are in effect creating a new market by resegmenting an existing one). Taken together, these two diagrams should clearly illustrate why thousands of new customers will believe in and move to this market.

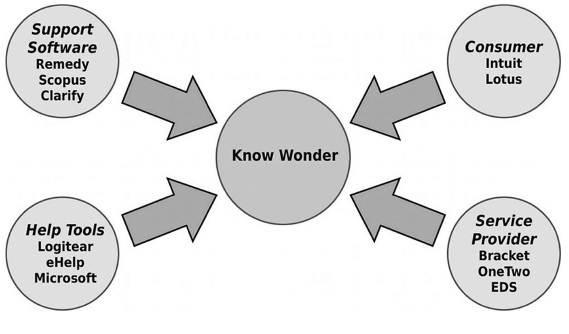

I have always found it helpful in a resegmented or new market to draw a “market map” (a diagram of how this new market will look) as shown in Figure 3.7. The map shows at a glance why the company is unique. A standing joke is that every new market has its own descriptive TLA (three-letter acronym). Draw the market map with your company in the center.

Figure 3.7 Example of a Market Map

A resegmented market assumes it is going to get customers from an existing market. Draw the existing markets from which you expect to get your customers (remember a market is a set of companies with common attributes.)

Market Type Hypotheses: Entering a New Market

At first glance, a new market has great appeal. What could be better than a market with no competitors? And no competition typically means pricing is not a competitive issue but one of what the market will bear. Wow, no competitors and high margins! Yet even without competitors the risks of market failure are great. Without sounding pedantic, creating a new market means a market does not currently exist—there are no customers. If you believe you are entering a new market, good questions to address in your brief include:

- What are the markets adjacent to the one you are creating?

- What markets will potential customers come from?

- What compelling need will make customers use/buy your product?

- What compelling feature will make them use/buy your product?

- How long will it take you to educate potential customers to grow a market of sufficient size? What size is that?

- How will you educate the market? How will you create demand?

- Given no customers yet exist, what are realistic year one-through-three sales forecasts?

- How much financing will it take to soldier on while you educate and grow the market?

- What will stop a well-heeled competitor from taking the market from you once you've developed it? (There is a reason the phrase “the pioneers are the ones with the arrows in their back” was coined.)

- Is it possible to define your product as either resegmenting a market or as entering an existing one?

As I noted in Chapter 2, you compete in a new market not by besting other companies with your product features, but by convincing a set of customers your vision is not a hallucination and solves a real problem they have or could be convinced they have. However, “who the users are” and the “definition of the market” itself are undefined and unknown. Here the key is to use your competitive brief to define a new market with your company in the center.

F. State Your Hypotheses: Competitive Hypotheses

Next, the Customer Development team assembles a competitive brief. Remember, if you are entering an existing market or resegmenting one, the basis of competition is all about some attribute(s) of your product. Therefore you need to know how and why your product is better than those of your competitors. This brief helps you focus on answering that question.

(If you are entering a new market, doing a competitive analysis is like dividing by zero; there are no direct competitors. Use the market map you developed in the last phase as a stand-in for a competitive hypothesis to answer the questions below as if each of the surrounding markets and companies will ultimately move into your new market.)

Take a look at the market you are going to enter and estimate how much market share the existing players have. Does any single entrant have 30 percent? Over 80 percent? These are magic numbers. When the share of the largest player in a market is around 30 percent or less, there is no single dominant company. You have a shot at entering this market. When one company owns over 80 percent share (think Microsoft), that player is the owner of the market and a monopolist. The only possible move you have is resegmenting this market. (See Chapter 5 for more details.)

- How have the existing competitors defined the basis of competition? Is it on product attributes? Service? What are their claims? Features? Why do you believe your company and product are different?

- Maybe your product allows customers to do something they could never do before. If you believe that, what makes you think customers will care? Is it because your product has better features? Better performance? A better channel? Better price?

- If this were a grocery store, which products would be shelved next to yours? These are your competitors. (Where would TiVo had been shelved, next to the VCRs or somewhere else?) Who are your closest competitors today? In features? In performance? In channel? In price? If there are no close competitors, who does the customer go to in order to get the equivalent of what you offer?

- What do you like most about each competitor's product? What do your customers like most about their products? If you could change one thing in a competitor's product, what would it be?

- In a company the questions might be: Who uses the competitors’ products today, by title and by function? How do these competitive products get used? Describe the workflow/design flow for an end user. Describe how it affects the company. What percentage of their time is spent using the product? How mission critical is it? With a consumer product, the questions are similar but focus on an individual.

- Since your product may not yet exist, what do people do today without it? Do they simply not do something or do they do it badly?

A natural tendency of startups is to compare themselves to other startups around them. That's looking at the wrong problem. In the first few years, other startups do not put each other out of business. While it is true startups compete with each other for funding and technical resources, the difference between winning and losing startups is that winners understand why customers buy. The losers never do. Consequently, in the Customer Development model, a competitive analysis starts with why customers will buy your product. Then it expands into a broader look at the entire market, which includes competitors, both established companies and other startups.

This brief completes your first and last large-scale paperwork exercise. The action now moves outside the building, where you will start to understand what potential customers need and thereby qualify your initial assumptions.

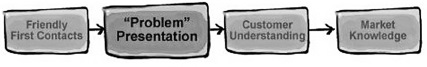

Phase 2: Test And Qualify Your Hypotheses

In this phase the Customer Development team begins to test and qualify the hypotheses assembled in Phase 1. I use the phrase “test and qualify assumptions,” because very rarely do hypotheses survive customer feedback intact. You won't simply be validating your hypotheses—you'll be modifying them as a result of what you learn from customers. Since all you have inside the company are opinions—the facts are with your customers—the founding team leaves the building and comes back only when the hypotheses have turned into data. In doing so, you will acquire a deep understanding of how customers work and more importantly, how they buy. In this phase you will make or acquire:

- First customer contacts

- The customer problem presentation

- In-depth customer understanding

- Market knowledge