CHAPTER 2

The Path to Epiphany: The Customer Development Model

How narrow the gate and constricted the road that leads to life. And those who find it are few.

— Matthew 7:14

THE FURNITURE BUSINESS DOES NOT STRIKE many people as ripe for innovation. Yet during the halcyon days of dot-com companies (when venture capitalists could not shovel money out the door fast enough), the online furnishing market spawned a series of high-profile companies such as Furniture.com and Living.com. Operating on the James Dean School of Management (living fast and dying young), companies like these quickly garnered millions of dollars of investors’ capital and just as swiftly flamed out. Meanwhile, a very different startup by the name of Design Within Reach began building its business a brick at a time. What happened, and why, is instructive.

At a time when the furniture dot-coms were still rolling in investor money, the founder of Design Within Reach, Rob Forbes, approached me to help the company get funding. Rob's goal was to build a catalog business providing easy access to well-designed furniture frequently found only in designer showrooms. In his 20 years of working as a professional office designer, he realized one of the big problems in the furniture industry for design professionals and businesses such as hotels and restaurants was that high-quality designer furniture took four months to ship. Customers repeatedly told Rob, “I wish I could buy great-looking furniture without having to wait months to get it.” On a shoestring, Rob put together a print catalog of furniture (over half the items were exclusive to his company) that he carried in stock and ready to ship. Rob spent his time listening to customers and furniture designers. He kept tuning his catalog and inventory to meet designers’ needs, and he scoured the world for unique furniture.

His fledgling business was starting to take wing; now he wanted to raise serious venture capital funding to grow the company.

“No problem,” I said. Pulling out my Rolodex and dialing for dollars, I got Rob in to see some of the best and brightest venture capitalists on Sand Hill Road in Silicon Valley. In each case, Rob went through his presentation and pointed out there was a $17.5 billion business-to-business market for high-quality, well-designed furnishings. He demonstrated that the current furniture distribution system was archaic, fragmented, and ripe for restructuring, as furniture manufacturers faced a convoluted system of reps, dealers, and regional showrooms preventing direct access to their customers. Consumers typically waited four months for product and incurred unnecessary markups of up to 40%. Listening to Rob speak, it was obvious he had identified a real problem, had developed a product that solved that problem, and had customers verifying he had the right solution by buying from him.

The presentation was so compelling that it was a challenge to identify any other industry where customers were so poorly served. Yet the reaction from the venture capital firms was uniformly negative. “What, no website? No e-commerce transactions? Where are the branding activities? We want to fund Web-based startups. Perhaps we'd be interested if you could turn your catalog furniture business into an e-commerce site.” Rob kept patiently explaining his business was oriented to what his customers told him they wanted. Design professionals wanted to leaf through a catalog at their leisure in bed. They wanted to show a catalog to their customers. While he wasn't going to ignore the Web, it would be the next step, not the first, in building the business.

“Rob,” the VCs replied sagely, “Furniture.com is one of the hottest dot-coms out there. Together they've raised over $100 million from first-tier VCs. They and other hot startups like them are selling furniture over the Web. Come back when you rethink your strategy.”

I couldn't believe it: Rob had a terrific solution to sell and a proven business model, and no one would fund him. The tenacious entrepreneur that he was, he stubbornly stuck to his guns. Rob believed the dot.com furniture industry was based on a false premise that the business opportunity was simply online purchasing of home furnishings. He believed the underlying opportunity was to offer to a select audience high-quality products that were differentiated from those of other suppliers, and to get those products to customers quickly. A select audience versus a wide audience, and high-quality furniture versus commodity furniture, were the crucial differences between success and massive failure.

Ultimately, Rob was able to raise money from friends and family and much later got a small infusion of venture capital. At its peak, Design Within Reach was a $180 million public company. It had both retail stores and an e-commerce website. Its brand was well-known and recognized in the design community. Furniture.com? It's been relegated to the dustbin of forgotten failures.

Why did Design Within Reach succeed, when extremely well-funded startups like Furniture.com fail? What did Rob Forbes know or do that made the company a winner? Can others emulate his success?

The Four Steps To The Epiphany

Most startups lack a process for discovering their markets, locating their first customers, validating their assumptions, and growing their business. A few successful ones like Design Within Reach do all these things. They succeed by inventing a Customer Development model.

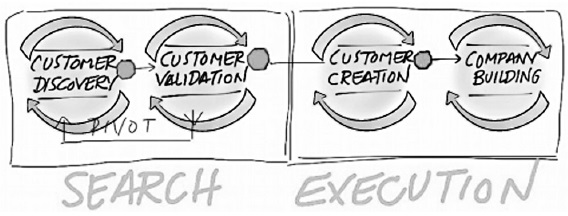

The Customer Development model, depicted in Figure 2.1, is designed to solve the 10 problems of the Product Development model enumerated in Chapter 1. Rigor and flexibility are its strengths. The model separates out all the customer-related activities in the early stage of a company into their own processes, designed as four easy-to-understand steps: Customer Discovery, Customer Validation, Customer Creation, and Company Building. These steps mesh seamlessly and support a startup's ongoing Product Development activities. Each results in specific deliverables to be described in subsequent chapters.

Figure 2.1 The Customer Development Model

The Customer Development model is not a replacement for the Product Development model, but a companion to it. Broadly speaking, Customer Discovery focuses on testing whether a company's business model is correct, specifically focused on whether the product solves customer problems and needs (this match of product features and customers is called Product/Market fit). Customer Validation develops a sales model that can be replicated, Customer Creation creates and drives end-user demand, and Company Building transitions the organization from one designed for learning and discovery to a well-oiled machine engineered for execution. As I discuss later in this chapter, integral to this model is the notion that Market Type choices affect how the company will deploy its sales, marketing and financial resources.

Notice a major difference between this model and the traditional Product Development model is that each step is drawn as a circular track with recursive arrows. The circles and arrows highlight the iterative nature of each step. That's a polite way of saying, “Unlike Product Development, finding the right customers and market is unpredictable, and we will screw it up several times before we get it right.” Experience with scores of startups shows that only in business school case studies does progress with customers happen in a nice linear fashion. The nature of finding a market and customers guarantees you will get it wrong several times. Therefore, unlike the Product Development model, the Customer Development model assumes it will take several iterations of each of the four steps. It's worth pondering this point for a moment, because this philosophy of “It's OK to screw it up if you plan to learn from it” is the heart of the methodology presented in this book.

In a Product Development diagram, going backwards is considered a failure. No wonder most startup businesspeople are embarrassed when they are out in the field learning, failing, and learning some more. The diagram they've used to date says, “Go left to right and you're a success. Go right to left, and you'll get fired.” Consequently, startup sales and marketing efforts tend to move forward even when it's patently obvious they haven't nailed the market. (Imagine trying that philosophy in Product Development for pacemakers or missiles.)

In contrast, the Customer Development diagram says going backwards is a natural and valuable part of learning and discovery. In this new methodology, you keep cycling through each step until you achieve “escape velocity” and generate enough success to carry you out and into the next step.

Notice the circle labeled Customer Validation in Figure 2.1 has an additional iterative loop, or pivot, going back to Customer Discovery. As you'll see later, Customer Validation is a key checkpoint in understanding whether you have a product customers want to buy and a roadmap of how to sell it. If you can't find enough paying customers in the Customer Validation step, the model returns you to Customer Discovery to rediscover what customers want and will pay for.

An interesting consequence of this process is that it keeps a startup at a low cashburn rate until the company has validated its business model by finding paying customers. In the first two steps of Customer Development, even an infinite amount of cash is useless, because it can only obscure whether you have found a market. (Having raised lots of money tempts you to give products away, steeply discount to buy early business, etc., all while saying, “We'll make it up later.” It rarely happens that way.) Since the Customer Development model assumes most startups cycle through these first two steps at least twice, it allows a well-managed company to carefully estimate and frugally husband its cash. The company doesn't build its non-Product Development teams (sales, marketing, business development) until it has proof in hand (a tested sales roadmap and valid purchase orders) that it has a business worth building. Once proof is obtained, the company can go through the last two steps of Customer Creation and Company Building to capitalize on the opportunity it has found and validated. The Customer Development process represents the best practices of winning startups. Describe this model to entrepreneurs who have taken their companies all the way to a public offering and beyond, and you'll get heads nodding in recognition. It's just until now, no one has ever explicitly mapped their journey to success. Even more surprising, while the Customer Development model with its iterative loops/pivots may sound like a new idea for entrepreneurs, it shares many features with a U.S. war-fighting strategy known as the “OODA Loop” articulated by John Boyd 1 and adopted by the U.S. armed forces in the second Gulf War. (You'll hear more about the OODA Loop later.)

The next four chapters provide a close-up look at each of the four steps in the model. The following overview will get you oriented to the process.

Step 1: Customer Discovery

The goal of Customer Discovery is just what the name implies: finding out who the customers for your product are and whether the problem you believe you are solving is important to them. More formally, this step involves discovering whether the problem, product and customer hypotheses in your business plan are correct. To do this, you need to leave guesswork behind and get “outside the building” in order to learn what the high-value customer problems are, what about your product solves these problems, and who specifically are your customer and user (for example, Who has the power to make or influence the buying decision and who will use the product on a daily basis?). What you learn will also help shape how you will describe your unique differences to potential customers. An important insight is that the goal of Customer Development is not to collect feature lists from prospective customers, nor is it to run lots of focus groups. In a startup, the founders and Product Development team define the first product. The job of the Customer Development team is to see whether there are customers and a market for that vision. (Read this last sentence again. It's not intuitively obvious, but the initial product specification comes from the founders’ vision, not the sum of a set of focus groups.)

The basic premise of Furniture.com and Living.com was a good one. Furniture shopping is time-consuming, and the selection at many stores can be overwhelming. On top of that, the wait for purchased items can seem interminable. While these online retailers had Product Development milestones, they lacked formal Customer Development milestones. At Furniture.com the focus was on getting to market first and fast. Furniture.com spent $7 million building its website, e-commerce and supply chain systems before the company knew what customer demand would be. Once the website was up and the supply chain was in place, it began shipping. Even when it found shipping and marketing costs were higher than planned, and brand-name manufacturers did not want to alienate their traditional retail outlets, the company pressed forward with its existing business plan.

In contrast, at Design Within Reach Rob Forbes was the consummate proponent of a customer-centric view. Rob was talking to customers and suppliers continually. He didn't spend time in his office pontificating about a vision for his business. Nor did he go out and start telling customers what products he was going to deliver (the natural instinct of any entrepreneur at this stage). Instead, he was out in the field listening, discovering how his customers worked and what their key problems were. Rob believed each new version of the Design Within Reach furniture catalog was a way for his company to learn from customers. As each subsequent catalog was developed, feedback from customers was combined with the sales results of the last catalog and the appropriate changes were made. Entire staff meetings were devoted to “lessons learned” and “what didn't work.” Consequently, as each new catalog hit the street the size of the average customer order and the number of new customers increased.

Step 2: Customer Validation

Customer Validation is where the rubber meets the road. The goal of this step is to build a repeatable sales roadmap for the sales and marketing teams that will follow later. The sales roadmap is the playbook of the proven and repeatable sales process that has been field-tested by successfully selling the product to early customers. Customer Validation proves you have found a set of customers and a market that react positively to the product. A customer purchase in this step validates lots of polite words from potential customers about your product.

In essence, Customer Discovery and Customer Validation corroborate your business model. Completing these first two steps verifies your market, locates your customers, tests the perceived value of your product, identifies the economic buyer, establishes your pricing and channel strategy, and checks out your sales cycle and process. If, and only if, you find a group of repeatable customers with a repeatable sales process, and then find those customers yield a profitable business model, do you move to the next step (scaling up and crossing the Chasm).

Design Within Reach started with a hypothesis that its customers fit a narrow profile of design professionals. It treated this idea like the educated guess it was, and tested the premise by analyzing the sales results of each catalog. It kept refining its assumptions until it found a repeatable and scalable sales and customer model.

This is where the dot.com furniture vendors should have stopped and regrouped. When customers did not respond as their business models predicted, further execution on the same failed plan guaranteed disaster.

Step 3: Customer Creation

Customer Creation builds on the success of the company's initial sales. Its goal is to create end-user demand and drive that demand into the company's sales channel. This step is placed after Customer Validation to move heavy marketing spending after the point where a startup acquires its first customers, thus allowing the company to control its cash-burn rate and protect its most precious asset.

The process of Customer Creation varies with the type of startup. As I noted in Chapter 1, startups are not all alike. Some startups enter existing markets well-defined by their competitors, some create new markets where no product or company exists, and some attempt a hybrid of the first two, resegmenting an existing market either as a low-cost entrant or by creating a niche. Each of these Market Type strategies requires a distinctive set of Customer Creation activities.

In Furniture.com's prospectus, the first bullet under growth strategy was “Establish a powerful brand.” Furniture.com launched a $20 million advertising campaign that included television, radio and online ads. It spent $34 million on marketing and advertising, even though revenue was just $10.9 million. (Another online furniture startup, Living.com, agreed to pay electronic-commerce giant Amazon.com $145 million over four years to be featured on Amazon's home page.) Brand building and heavy advertising make lots of sense in existing markets when customers understand your product or service. However, in a new market this type of “onslaught” product launch is like throwing money down the toilet. Customers have no clue what you are talking about, and you have no idea if they will behave as you assume.

Step 4: Company Building

Company Building is where the company transitions from its informal, learning and discovery-oriented Customer Development team into formal departments with VPs of Sales, Marketing and Business Development. These executives now focus on building mission-oriented departments exploiting the company's early market success.

In contrast to this incremental process, premature scaling is the bane of startups. By the time Furniture.com had reached $10 million in sales, it had 209 employees and a burn rate that would prove to be catastrophic if any of its business plan assumptions were incorrect. The approach seemed to be to “spend as much as possible on customer acquisition before the music stops.” Delivering heavy furniture from multiple manufacturers resulted in unhappy customers as items got damaged, lost, or delayed. Flush with investors’ cash, the company responded the way dot-coms tend to respond to problems: by spending money. It reordered, and duplicates began piling up in warehouses. The company burned through investor dollars like cheap kindling. Furniture.com went from filing for a public offering in January to pulling its IPO in June 2000 and talking with bankruptcy lawyers. The company was eventually able to raise $27 million in venture funding, but at a lower valuation than the last time it raised money. In a bid for survival, Furniture.com furiously slashed costs. The company, which had been offering free shipping for delivery and returns, began charging a $95 delivery charge. Then it laid off 41% of its staff. But it never answered the key question: Is there a way to sell commodity furniture over the Web and ship it cost-effectively when you don't have a nationwide network of stores?

At Design Within Reach, Rob Forbes ran the company on a shoestring. The burn rate was kept low, first as a necessity as he scraped together financing, and then by plan as his team was finding a sales roadmap that could scale. Rob was finding a way to sell furniture without a network of stores - it was called a catalog.

The Four Types Of Startup Markets

Since time immemorial the postmortem of a failed company has typically included, “I don't understand what happened. We did everything that worked in our last startup.” The failure isn't due to lack of energy, effort or passion. It may simply be not understanding there are four types of startups, each of them needing a very different set of requirements to succeed:

- Startups that are entering an existing market

- Startups that are creating an entirely new market

- Startups that want to resegment an existing market as a low-cost entrant

- Startups that want to resegment an existing market as a niche player

(“Disruptive” and “sustaining” innovations, eloquently described by Clayton Christensen, are another way to define new and existing Market Types.)

As I pointed out in Chapter 1, thinking and acting as if all startups are the same is a strategic error. It is a fallacy to believe the strategy and tactics that worked for one startup should be appropriate in another. That's because Market Type changes everything a company does.

As an example, imagine it's October 1999 and you are Donna Dubinsky, CEO of a feisty new startup, Handspring, in the billion dollar Personal Digital Assistant (PDA) market. Other companies in the 1999 PDA market were Palm, the original innovator; as well as Microsoft and Hewlett Packard. In October 1999 Donna told her VP of Sales, “In the next 12 months I want Handspring to win 20% of the Personal Digital Assistant market.” The VP of Sales swallowed hard, turned to the VP of Marketing and said, “I need you to take end-user demand away from our competitors and drive it into our sales channel.” The VP of Marketing looked at all the other PDAs on the market and differentiated Handspring's product by emphasizing expandability and performance. End result? After 12 months Handspring's revenue was $170 million.

This was possible because in 1999 Donna and Handspring were in an existing market. Handspring's customers understood what a Personal Digital Assistant was. Handspring did not have to educate them about the market, just why their new product was better than the competition – and they did it brilliantly.

For comparison, now rewind the story three years earlier, to 1996. Before Handspring, Donna and her team had founded Palm Computing, the pioneer in Personal Digital Assistants. Before Palm arrived on the scene the Personal Digital Assistant market did not exist. (A few failed science experiments like Apple's Newton had come and gone.) Imagine if Donna had turned to her VP of Sales at Palm in 1996 and said, “I want to get 20% of the Personal Digital Assistant market by the end of our first year.” Her VP of Sales might had turned to the VP of Marketing and said, “I want you to drive enduser demand from our competitors into our sales channel.” The VP of Marketing might have said, “Let's tell everyone about how fast the Palm Personal Digital Assistant is.” If they had done this there would have been no sales. In 1996 no potential customer had heard of a Personal Digital Assistant. No one knew what a PDA could do, there was no latent demand from end users, and emphasizing its technical features would have been irrelevant. Palm needed to educate potential customers about what a PDA could do for them. By our definition (a product that allows users to do something they couldn't do before), Palm in 1996 created a new market. In contrast, Handspring in 1999 was in an existing market.

The lesson? Even with essentially identical products and team, Handspring would have failed if it had used the same sales and marketing strategy used successfully at Palm. And the converse is true: Palm would have failed, burning through all its cash, using Handspring's strategy. Market Type changes everything – how you evaluate customer needs and customer adoption rate, how the customer understands his needs and how you would position the product to the customer. Market Type also changes the market size, as well as how you launch the product into the market. Table 2.1 points out what's different.

Table 2.1 Market Type Affects Everything

| Customer | Market | Sales | Finance |

| Needs | Market Size | Distribution channel | On going capital |

| Adoption Rate | Cost of entry | Margins | Time to profitability |

| Problem Recognition | Launch Type | Sales cycle | |

| Positioning | Competitive Barriers |

Before any sales or marketing activities can begin, a company must keep testing and asking, “What kind of a startup are we?” To see why, consider the four possible “Market Types.”

A New Product in an Existing Market

An existing market is easy to understand. You are in an existing market if your product offers higher performance than what is currently offered. Higher performance can be a product or service that runs faster, does something better or substantially improves on what is already on the market. The good news is the users and the market are known, but so are the competitors. In fact, competitors define the market. The basis of competition is therefore all about the product and product features.

You can enter an existing market with a cheaper or repositioned “niche” product, but if that is the case we call it a resegmented market.

A New Product in a New Market

Another possibility is to introduce a new product into a new market. A new market results when a company creates a large customer base that couldn't do something before. This happens because of true innovation, creating something brand-new; dramatically lower cost, creating a new class of users; or because the new product solves availability, skill, convenience, or location issues in a way no other product has. Compaq's first portable computers allowed business executives to take their computers with them, something simply impossible previously. Compaq created a new market, the portable computer market. With Quicken, Intuit offered people a way to manage their finances on their personal computers, automating check writing, maintaining a check register and reconciling monthly balances – things most people hated to do and few could do well. In doing so, Intuit created the home accounting market. (By “created the market” I do not mean “first-to-market”; I mean the company whose market share and ubiquity are associated with the market.)

In a new market the good news is your product features are at first irrelevant because there are no competitors (except other pesky startups). The bad news is the users and the market are undefined and unknown. If you're creating a new market, your problem isn't how to compete with other companies on product features but how to convince a set of customers your vision is not a hallucination. Creating a new market requires you to understand whether there is a large customer base that couldn't do this before, whether these customers can be convinced they want or need your new product, and whether customer adoption occurs in your lifetime. It also requires rather sophisticated thinking about financing—how you manage the cash-burn rate during the adoption phase, and how you manage and find investors who are patient and have deep pockets.

A New Product Attempting to Resegment an Existing Market: Low Cost

Over half of startups pursue the hybrid course of attempting to introduce a new product that resegments an existing market. Resegmenting a market can take two forms: a low-cost strategy or a niche strategy. (Segmentation is not the same as differentiation. Segmentation means you've picked a clear and distinct spot in customers’ minds that is unique, understandable, and, most important, concerns something they value and want and need now.)

Low-cost resegmentation is just what it sounds like—are there customers at the low end of an existing marketing who will buy “good enough” performance if they could get it at a substantially lower price? If you truly can be a low-cost (and profitable) provider, entering existing markets at this end is fun, as incumbent companies tend to abandon low-margin businesses and head up-market.

A New Product Attempting to Resegment an Existing Market: Niche

Niche resegmentation is slightly different. It looks at an existing market and asks, “Would some part of this market buy a new product designed to address their specific needs? Even if it cost more? Or had worse performance in an aspect of the product irrelevant to this niche?’

Niche resegmentation attempts to convince customers some characteristic of the new product is radical enough to change the rules and shape of an existing market. Unlike low-cost resegmentation, niche goes after the core of an existing market's profitable business.

Both cases of resegmenting a market reframe how people think about the products within an existing market. In-n-Out Burger is a classic case of resegmenting an existing market. Who would have thought a new fast-food chain (now with 200 companyowned stores) could be a successful entrant after McDonald's and Burger King owned the market? Yet In-n-Out succeeded by simply observing the incumbent players had strayed from their original concept of a hamburger chain. By 2001 McDonald's had over 55 menu items and not one of them tasted particularly great. In stark contrast, Inn-Out offered three items: all fresh, high-quality and great tasting. They focused on the core fast-food segment that wanted high-quality hamburgers and nothing else.

While resegmenting an existing market is the most common Market Type choice of new startups, it's also the trickiest. As a low-end resegmentation strategy, it needs a long-term product plan that uses low cost as market entry to eventual profitability and up-market growth. As a niche resegmentation, this strategy faces entrenched competitors who will fiercely defend their profitable markets. And both require adroit and agile positioning of how the new product redefines the market.

Market Type and the Customer Development Process

As a company follows the Customer Development process the importance of Market Type grows in each step. During the first step, Customer Discovery, all startups, regardless of Market Type, leave the building and talk to customers. In Customer Validation, the differences between type of startup emerge as sales and positioning strategies diverge rapidly. By Customer Creation, the third step, the difference between startup Market Types is acute as customer acquisition and sales strategy differ dramatically between the types of markets. It is in Customer Creation that startups that do not understand Market Type spend themselves out of business. Chapter 5, Customer Creation, highlights these potential landmines.

The speed with which a company moves through the Customer Development process also depends on Market Type. Even if you quit your old job on Friday and on Monday join a startup in an existing market producing the same but better product, you still need to answer these questions. This process ought to be a snap, and can be accomplished in a matter of weeks or months.

In contrast, a company creating a new market has an open-ended set of questions. Completing the Customer Development processes may take a year or two, or even longer.

Table 2.2 sums up the differences among Market Types. As you'll see, the Customer Development model provides an explicit methodology for answering “What kind of startup are we?” It's a question you'll return to in each of the four steps.

Table 2.2 “Market Type” Characteristics

| Existing Market | Resegmented Market | New Market | |

| Customers | Existing | Existing | New/New usage |

| Customer Needs | Performance |

|

Simplicity & convenience |

| Performance | Better/faster |

|

Low in traditional attributes improved by new customer metrics |

| Competition | Existing incumbents | Existing incumbents | Non-consumption/other startups |

| Risks | Existing incumbents |

|

Market adoption |

Synchronizing Product Development And Customer Development

As I suggested in Chapter 1, Customer Development is not a substitute for the activities occurring in the Product Development group. Instead, Customer Development and Product Development are parallel processes. While the Customer Development group is engaged in customer-centric activities outside the building, the Product Development group is focused on the product-centric activities taking place internally. At first glance, it might seem there isn't much connection between the two. This is a mistake. For a startup to succeed, Product and Customer Development must remain synchronized and operate in concert.

However, the ways the two groups interact in a startup are 180 degrees from how they would interact in a large company. Engineering's job in large companies is to make follow-on products for an existing market. A follow-on product starts with several things already known: who the customers are, what they need, what markets they are in, and who the company's competitors are. (All the benefits of being in an existing market plus having customers and revenue.) The interaction in a large company between Product Development and Customer Development is geared to delivering additional features and functions to existing customers at a price that maximizes market share and profitability.

In contrast, most startups can only guess who their customers are and what markets they are in. The only certainty on day one is the product vision. It follows, then, the goal of Customer Development in a startup is to find a market for the product as spec'd, not to develop or refine a spec based on a market that is unknown. This is a fundamental difference between a big company and most startups.

Put another way, big companies tailor their Product Development to known customers. Product features emerge by successive refinement against known customer and market requirements and a known competitive environment. As the product features get locked down, how well the product will do with those customers and markets becomes clearer. Startups, however, begin with a known product spec and tailor their Product Development to unknown customers. Product features emerge by vision and fiat against unknown customer and market requirements. As the market and customers get clearer by successive refinement, product features are driven by how well they satisfy this market. In short, in big companies, the product spec is market-driven; in startups, the marketing is product-driven.

In both cases, Product and Customer Development must go hand in hand. In most startups the only formal synchronization between Engineering and the sales/marketing teams is when they line up for contentious battles. Engineering says, “How could you have promised these features to customers? We're not building that.” Sales responds, “Why is the product missing all the features you promised would be in this release? We need to commit to these other features to get an order.” A goal of a formal Customer Development process is to ensure the focus on the product and the focus on the customer remain in concert without rancor and with a modicum of surprise. The emphasis on synchronization runs through the entire Customer Development process.

A few examples of synchronization points are:

- In each step—Customer Discovery, Customer Validation, Customer Creation and Company Building—the Product Development and Customer Development teams hold a series of formal “synchronization” meetings. Unless the two groups agree, Customer Development does not move forward to the next step.

- In Customer Discovery, the Customer Development team strives to validate the product spec, not come up with a new set of features. Only if customers do not agree there's a problem to be solved, think the problem is not painful, or don't deem the product spec solves their problem, do the Customer and Product Development teams reconvene to add or refine features.

- Also in Customer Discovery, when customers have consistently said that new or modified product features are required, the VP of Product Development goes out with the team to listen to customer feedback before new features are added.

- In Customer Validation, key members of the Product Development team go out in front of customers as part of the pre-sales support team.

- In Company Building, the Product Development team does installations and support for initial product while training the support and service staff.

Summary: The Customer Development Process

The Customer Development model consists of four well-defined steps: Customer Discovery, Customer Validation, Customer Creation, and Company Building. As you will see in succeeding chapters, each of these steps has a set of clear, concise deliverablesgiving the company and its investors incontrovertible proof that progress is being made on the customer front. Moreover, the first three steps of Customer Development can be accomplished with a staff that can fit in a phone booth.

While each step has its own specific objectives, the process as a whole has one overarching goal: proving there is a profitable, scalable business for the company. This is what propels the company from nonprofit to moneymaking endeavor.

Being a great entrepreneur means finding the path through the fog, confusion and myriad of choices. To do that, you need vision and a process. This book gives you the process. Its premise is simple: If you execute the four steps of Customer Development rigorously and thoroughly, you increase the odds of achieving success, and you can reach the epiphany.

Note

- 1P Air War College, John R. Boyd, “Patterns of Conflict” and “A Discourse on Winning and Losing”