CHAPTER 4:

Customer Validation

Along the journey we commonly forget its goal.

— Friedrich Nietzsche

WHEN I MET CHIP STEVENS IN 2002, he thought his startup, InLook, was on the road to success. Twenty months earlier, he had raised $8 million to build a new class of enterprise software for Fortune 1000 companies. Chip's product, Snapshot, would allow the chief financial officers of major corporations to manage profitability before the quarter closed. Snapshot measured every deal in a company's sales pipeline and compared the deals to top-and bottom-line corporate financial objectives. The software was able to forecast margin, revenue, and product mix, and allow a company to allocate resources before a deal closed. This meant sales cycles could be shorter, fewer deals needed to be escalated to senior management, and management could allocate resources to the best deals in the pipeline. While Snapshot could save a company substantial dollars in the long term, it was expensive, costing $250,000 or more.

Chip had raised his money in a tough economic climate, and while the economy still hadn't recovered, he was relatively happy with the state of his company. Product Development, after being seriously broken for the first year, was back on track. Chip had to personally take over engineering management for a while, but since his background included a stint as a VP and general manager, he felt he handled it well. Fifteen months after receiving funding, InLook shipped its first product.

About eight months before we met, Chip hired Bob Collins as his VP of Sales. Bob had never been the first VP of Sales in a startup, but he had a track record as a successful sales executive, and had built and scaled the sales force in his previous company. Bob joined InLook three months before the product shipped and helped the company find its beta customers. As is true at most startups, InLook's beta customers didn't pay for the product, but Bob had high hopes of turning them into the first paying customers. Following the traditional Product Development model, Bob hired five salespeople: two on the West Coast, one in Chicago, one in Dallas, and one in New York. The salespeople were supported by four sales engineers they could talk to about the technical aspects of the product. Backing up Bob's sales team was a two-person marketing department writing data sheets and sales presentations. In total, InLook had an 11-person team working on sales, and no revenue to date. Bob's budget called for doubling the sales team by the end of the year.

While Bob was busy interviewing, the board was getting nervous. While the venture capitalists on the board thought Chip was a seasoned executive competently managing the company, InLook had yet to close a major customer deal and was missing its revenue plan. It was at this point that I entered the picture. The venture capitalists that provided InLook with its first round of funding had seen one of my early Customer Development lectures. They asked me to take a peek at InLook and see whether there was anything glaringly broken. (I believe their exact words were, “Take a look and see if their positioning needs help.”)

At our first meeting, Chip Stevens had the look of a busy startup CEO with much better things to do than take a meeting his venture capitalists had foisted on him. He listened politely as I described the Customer Development process and went through the milestones of Customer Discovery. Then it was Chip's turn, and he walked me through his company, his product, and his sales team. He ticked off the names of 40 or so customers he talked to during the company's first nine months and gave me a great dissertation on how his target customers worked and what their problems were. He went through his product feature by feature and matched them to the customer problems. He talked about how his business model would make money and how the prospects he talked to seem to agree with his assumptions. It certainly sounded like he had gotten Customer Discovery correct.

Next, Chip took me through his sales process. He told me that since he had been tied up getting the product out the door, he had stopped talking to customers, and his VP of Sales, Bob, had managed the sales process. In fact, the few times he had asked to go out in the field Bob said, “Not yet, I don't want to waste your time.” For the first time I started squirming in my seat. Chip said, “We have a great sales pipeline. I insist on getting weekly status reports with forecasted deal size and probability of close.” When I asked how close any of the deals on the forecast were to getting closed, he assured me the company's two beta customers—well-known companies that would be marquee accounts if they closed—were imminent orders.

“How do you know this?” I asked. “Have you heard it personally from the customers?”

Now it was Chip's turn to squirm a bit. “No, not exactly,” he replied, “but Bob assures me we will have a purchase order in the next few weeks or so.”

Now I really was nervous for Chip and his company. Very few large companies write big checks to unknown startups without at least meeting the CEO, if not talking to a few of the venture capitalists on the board. When I asked if Chip could draw the sales roadmap for these two accounts that were about to close, he admitted he didn't know any of the details, given it was all in Bob's head. Since we were running out of time, I said, “Chip, your sales pipeline sounds great. In fact, it sounds too good to be true. If you really close any of these imminent accounts, my hat is off to you and your sales team. If, as I suspect, they don't close, do me a favor.”

“What's that?” Chip asked, looking irritated.

“You need to pick up the phone and call the top five accounts on your sales pipeline. Ask them this: If you give them your product today for free, are they prepared to install and use it across their department and company? If the answer is no, you have absolutely no customers on your forecast who will be prepared to buy from you in the next six months.”

Chip smiled and politely walked me out of his office. I didn't expect to hear from him again.

Less than two weeks later, I picked up my voicemail and was surprised to hear the agitated voice of Chip Stevens. “Steve, we really have to talk again. Our brand-name account, the one we have been working on for the last eight months, told us they weren't going to buy the product this year. They just didn't see the urgency.” Calling Chip back, I got the rest of the story.

“When my VP of Sales told me that,” Chip said, “I got on the phone and spoke to the account personally. I asked them your question—would they deploy the product in their department or company if the price were zero? I'm still stunned by the answer. They said the product wasn't mission critical enough for their company to justify the disruption.”

“Wow, that's not good,” I said, trying to sound sympathetic.

“It only gets worse,” he said. “Since I was hearing this from one of the accounts my VP of Sales thought was going to close, I insisted we jointly call our other ‘imminent’ account. It's the same story as the first. Then I called the next three down the list and got essentially the same story. They all think our product is ‘interesting,’ but no one is ready to put serious money down now. I'm beginning to suspect our entire forecast is not real. What am I going to tell my board?”

My not-so-difficult advice was that Chip would have to tell his board exactly what was going on. But before he did, he needed to understand the sales situation in its entirety, then come up with a plan for fixing it. Then he was going to present both the problem and suggested fix to his board. (You never want a board to have to tell you how to run your company. When that happens, it's time to update your resume.)

Chip had only begun to understand the implications of a phantom sales forecast, and he began to dig further. In talking to each of his five salespeople, he discovered the InLook sales team had no standardized sales process. Each salesperson was calling on different levels of an account and trying whatever seemed to work best. When he talked to his marketing people, he found they were trying to help sales by making up new corporate presentations almost weekly. The company's message and positioning were changing week by week. Bob, his VP of Sales, believed there was nothing really wrong. They just needed more time to “figure it out” and then they would close a few accounts.

With his company burning cash fast (11 people in sales and marketing), no real understanding of what was broken in sales, and no revenue in the pipeline, the Japanese Noh play was about to unfold again. Bob was about to become history. The “good” news was that as an agile and experienced business executive, Chip quickly understood what had gone wrong. He came to grips with the fact that after eight months InLook still did not have a clue about how to sell Snapshot. Worse, there was no process in place to learn how to sell, just a hope that smart salespeople would “find their way.” Chip realized the company would have to start from scratch and develop a sales roadmap. He presented his plan to the board, fired the VP of Sales and seven of the sales and marketing staff, and dramatically slashed the company's burn rate. He kept his best salesperson and support engineer as well as the marketing VP. Then Chip went home, kissed his family goodbye, and went out to the field to discover what would make a customer buy. Chip's board agreed with his conclusion, wished him luck and started the clock ticking on his remaining tenure. He had six months to get and close customers.

Chip had discovered InLook lacked what every startup needs: a method that allows it to develop a predictable sales process and validate its business model. After Customer Discovery, startups must next ask and answer basic questions such as:

- Are we sure we have product/market fit?

- Do we understand the sales process?

- Is the sales process repeatable?

- Can we prove it's repeatable? (What's the proof? Full-price orders for a sale in sufficient quantity.)

- Can we get these orders with the current product and release spec?

- Have we correctly positioned the product and the company?

- Do we have a workable sales and distribution channel?

- Are we confident we can scale a profitable business?

Contrary to what happened at InLook (and what happens in countless startups), the Customer Development model insists these questions be asked and answered long before the sales organization begins to grow. Getting them answered is the basic goal of Customer Validation.

The Customer Validation Philosophy

Just as Customer Discovery was disorienting for experienced marketers, the Customer Validation process turns the world upside down for experienced salespeople, and in particular, Sales VPs. None of the rules sales executives learned in large companies apply to startups—in fact they are detrimental. In the Customer Validation step, you are not going to staff a sales team. You are not going to execute to a sales plan, and you are definitely not going to execute your “sales strategy.” You simply do not know enough to do any of these things. You may have hypotheses about who will buy, why they will buy, and at what price they will buy, but until you validate them, they are merely educated guesses.

One of the major outcomes of Customer Validation is a proven and tested sales roadmap. You will create this map by learning how to sell to a small set of early visionary customers (earlyvangelists). They will pay for the product—sometimes months or even years before it is completed. However, the goal of this step is not to be confused with “selling.” The reality is you care less about generating revenue at this point than you do about finding a scalable and repeatable sales process and business model. Building a roadmap to sales success, rather than building a sales organization, is the heart of Customer Validation. Given how critical this step is, a CEO's first instinct is to speed up the process by putting more salespeople in the field. This only slows the process.

In an existing market, Customer Validation may prove the VP of Sales’ Rolodex is truly relevant and the metrics for product performance the company identified in Customer Discovery were correct. In a resegmented or new market, even a Rolodex of infinite size will not substitute for a tested sales roadmap.

For an experienced sales executive, these are heretical statements. They are disorienting and seem counterintuitive to what sales professionals have been trained to do. So let's look more closely at why the first sales in a startup are so different from later-stage sales or selling in a large company.

Validating the Sales Process

Ask startup Sales VPs what their top two or three goals are, and you'll get answers like, “To achieve our revenue plan,” or “To hire and staff our sales organization, and then to achieve our revenue plan.” Some might add, “To help engineering understand what additional features our customers need.” In short, you'll get answers that are usually revenue-and head count-driven. While goals like these are rational for an established company, they are anything but rational for startups. Why? In established companies, someone has already blazed the trail through the swamp. New salespeople are handed a corporate presentation, price list, data sheets, and all the other accoutrements of a tested sales process. The sales organization has a sales pipeline with measured steps and a sales roadmap with detailed goals, all of which have been validated by experience with customers. A sales pipeline is the traditional sales funnel. Wide at the top with raw leads coming into it, it narrows at each stage as the leads get qualified and turn into suspects, then prospects, then probable closes, until finally an order comes out of the narrow end of the funnel. Nearly all companies with a mature sales force have their own version of this sales funnel. They use it to forecast revenue and the probability of success of each prospect. Most experienced Sales VPs hired into new startups will attempt to replicate the funnel by assembling a sales pipeline and filling it with customers. What they don't recognize is that it is impossible to build a sales pipeline without first having developed a sales roadmap.

A sales roadmap answers the basic questions involved in selling your product: Are we sure we have product/market fit? Who influences a sale? Who recommends a sale? Who is the decision-maker? Who is the economic buyer? Who is the saboteur? Where is the budget for purchasing the type of product you're selling? How many sales calls are needed per sale? How long does an average sale take from beginning to end? What is the selling strategy? Is this a solution sale? If so what are “key customer problems”? What is the profile of the optimal visionary buyer, the earlyvangelist every startup needs?

Unless a company has proven answers to these questions, few sales will happen, and those that occur will be the result of heroic, single-shot efforts. Of course, on some level most sales VPs realize they lack the knowledge they need to draw a detailed sales roadmap, but they believe they and their newly hired sales team can acquire this information while simultaneously selling and closing orders. This is a manifestation of one of the fundamental fallacies of the traditional Product Development methodology when applied to startups. You cannot learn and discover while you are executing. As we can see from the example of InLook, and from the rubble of any number of failed startups, attempting to execute before you have a sales roadmap in place is pure folly.

The Customer Validation Team

The InLook story illustrates one of the classic mistakes startup founders and CEOs typically make: delegating the Customer Validation process solely to the VP of Sales. In technology companies, a majority of founders are engineers and assume they need to hire a professional in a domain where they have no expertise. And in the case of a VP of Sales, they're probably hiring a professional who is proud of his or her skill and Rolodex. So the founders’ natural tendency is to stay away and trust the abilities of their hires. This mistake is usually fatal for the VP of Sales and sometimes for the startup as well.

Sales execution is the responsibility of the VP of Sales. Sales staffing is the responsibility of the VP of Sales. Yet at this point in the life of a startup, you don't know enough to be executing or staffing anything. Your startup is still in learning mode, and your Customer Development team needs to continue to lead customer interaction through Customer Validation.

At a minimum, the company's founders and CEO need to be out in front of customers at least through the first iteration of the Customer Validation step. They are the people who, with help from the product team, can find their visionary peers, excite them about a product, and get them ready to buy. In enterprise or BtoB sales, if the founding team does not include someone with the skill to close an account, the company can hire a “sales closer,” a salesperson with the skills to close a deal.

Early Sales Are to Earlyvangelists, Not Mainstream Customers

In Customer Validation, your startup is focused on finding the visionary customers and getting them to make a purchase.

Unlike “mainstream” customers who want to buy a finished, completed, and tested product, earlyvangelists are willing to make a leap of faith and buy from a startup. They may do so because they perceive a competitive advantage in the market, bragging rights with peers in their neighborhood or in an industry, or political advantage within their company. Earlyvangelists are the only customers able to buy a yet-to-be-delivered, unfinished product.

Recall who these visionary customers are. They not only understand they have a problem, but they have spent time actively looking for a solution, to the point of trying to build their own. In a company this may be because there is a broken mission-critical business process that needs to be fixed. Therefore, when you walk through the door, they immediately grasp the problem you are solving is one they have, and they can see the elegance and value of your solution. Little or no education is needed. In other cases their motivation might be that they are driven by competitive advantage and will take a risk on a new paradigm to get it.

Earlyvangelists “get it.” However, they usually don't or won't get it from a “suit,” a traditional salesperson. Earlyvangelists want to see and hear the founders and the technical team. In exchange, you will not only get an order and great feedback, but visionary customers will become earlyvangelists inside their companies and throughout their industry—or as consumers, to their friends and neighbors. Treated correctly they are the ultimate reference accounts. (Until you reach the Chasm in Chapter 6.)

There's one important caveat about earlyvangelists. Some startup founders think of earlyvangelists as only being found in the research and development labs, or the technical evaluation groups of large corporate customers—or for a consumer product, someone lucky enough to work in a new product test lab where their job is to evaluate products for potential use. These are emphatically not the earlyvangelists I'm referring to. At times, they may be critical influencers in a sale, but they have no day-to-day operational role, and no authority for ensuring widespread adoption and deployment. The earlyvangelists you need to talk to are the people I described in Customer Discovery—the ones who are in operating roles, have a problem, have been looking for a solution, have tried to solve the problem and have a budget.

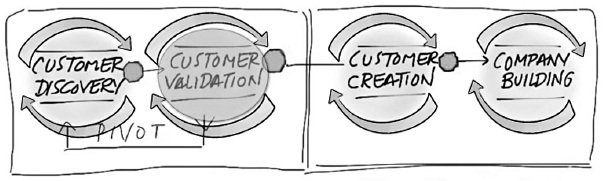

Customer Validation has four phases, as depicted in Figure 4.1. Phase 1 consists of a series of “getting ready to sell” activities: articulating a value proposition; preparing sales materials and a preliminary collateral plan; developing a distribution channel plan and a sales roadmap; hiring a sales closer; ensuring that your Product and Customer Development teams agree about product features and dates; and formalizing your advisory board.

Figure 4.1 Customer Validation: Overview of the Process

Overview of the Customer Validation Process

Next, in Phase 2, you leave the building and put your now well-honed product idea to the test: Will customers validate your concept by purchasing your product? You will attempt to sell customers an unfinished and unproven product, without a professional sales organization. Failures are as important as successes in this phase; the goal is to answer all the sales roadmap questions. At the end of this phase, you have preliminary meetings with channel or professional service partners.

With a couple of orders under your belt, you have enough customer information to move to Phase 3, in which you take your first cut at an initial positioning of the product and of the company. Here is where you articulate your profound belief about your product and its place in the market. You test this initial positioning by meeting with industry pundits and analysts for their feedback and approval.

Finally, in Phase 4, you verify whether the company is finished with Customer Validation. Do you have enough orders proving your product solves customer needs? Do you have a profitable sales and channel model? Do you have a profitable business model? Have you learned enough to scale the business? Only if you can answer yes to all these questions do you proceed to Customer Creation.

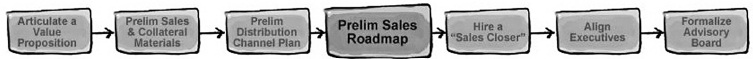

Phase 1: Get Ready to Sell

The initial phase of Customer Validation prepares the company for its first attempt at selling a product, which requires careful preparation, planning and concurrence. In particular, in this phase you will:

- Articulate a value proposition

- Prepare sales materials and a preliminary collateral plan

- Develop a preliminary distribution channel plan

- Develop a preliminary sales roadmap

- Hire a sales closer

- Align your executives

- Formalize your advisory board

A. Get Ready to Sell: Articulate a Value Proposition

From the customer perspective, what does your company stand for, what does your product do, and why should they care? You probably had an idea when you started the company, but now you have some real experience interacting with customers, and can revisit your vision in light of what you have learned. Can you reduce your business to a single, clear, compelling message that says why your company is different and your product is worth buying? That's the goal of a value proposition (sometimes called a unique selling proposition). A value proposition builds the bond between you and your customer, focuses marketing programs, and becomes the focal point for building the company. More relevant for this step, it gets the company's story down to an “elevator pitch,” one powerful enough to raise a customer's heart rate. This value proposition will appear in all your sales materials from here on out. It is the sum of all you have learned about product/market fit in Customer Discovery. Don't worry about getting it perfect, because it will change, evolve, and mutate as you get feedback from customers, analysts, and investors. The idea of this phase is simply to acknowledge you need to craft and create one, and take your best shot at articulating it.

While a value proposition seems straightforward, it can be a challenge to execute. It takes serious work to get to a pithy statement that is both understandable and compelling. It's much easier to write (or think) long than to write (or think) short. The first step is to remember what you have learned in Customer Discovery about customers’ problems, and what customers valued about your solution. What were the top three problems your customers said they had? Did a phrase keep coming up to describe this problem or the solution to the problem? Based on your understanding of how customers work, spend their time, or use other products, where does your product affect these customers most? How significant is the impact on how they work? If there are existing competitors or ways to solve the problem that use pieces of other solutions, what do you provide that your competitors can't or won't? What do you do better?

InLook's value proposition was, “Helping chief financial officers manage profitability.” Short and to the point, it played right to the audience InLook was going after. A value proposition is (ideally) one sentence, and at most a few sentences. How did the founders know who their audience was? They went back to all they learned in Customer Discovery. The CFO was now their target audience (he wasn't when they first started Customer Discovery), “profitability” was an emotionally compelling word (they had a litany of words when they first started talking to customers), and managing profitability was a leverage point quantifiable in the minds of their customers (a point they were clueless about earlier).

One of the first tests of your value proposition should be, is it emotionally compelling? Do customers’ heart rates go up after they hear it? Do they lean forward to hear more? Or do they give you a blank stare? Is the value proposition understandable in the users’ language? Is it unique in their minds? In technology startups, one of the biggest challenges for engineers is to realize they want an oversimplified message, one that grabs customers’ hearts and wallets, not their heads and calculators.

Second, does your value proposition make or reinforce an economic case? Does it have economic impact? Does it sound like your product gives a corporate customer a competitive advantage or improves some critical area in their company? If it's a consumer product, does it save a consumer time or money, or change their prestige or identity? The InLook example used the words “manage profitability.” To a CFO these powerful words represent a quantifiable and measurable benefit.

Finally, does the value proposition pass the reality test? Claims like “lose 30 pounds as fat just melts away,” “sales will increase 200 percent” or “cut costs by 50 percent” strain credibility. Moreover, the claim isn't the only thing that must pass this test. Is your company a credible supplier for the product you're describing? When selling to corporate customers, there are additional hurdles to think about. Are your capabilities congruent with your claims? Are your solutions attainable and compatible with customers’ current operations? Do customers have complementary or supporting technologies in place?

One last thing to keep in mind is our continual question about Market Type. If you are offering a new product in an existing market, your value proposition is about incremental performance. Incremental value propositions describe improvements and metrics of individual attributes of the product or service (i.e., faster, better). If you are creating a new market, or trying to reframe an existing one, you will probably come up with a transformational value proposition. Transformational value propositions deal with how the solution will create a new level or class of activity—i.e. something people could not do before.

B. Get Ready to Sell: Prepare a Preliminary Collateral Plan

Once you have a value proposition, it's time to put it to work in sales and marketing collateral. This is the sum of the printed and electronic communications your sales team will hand or present to potential customers. To sell a product in the Customer Validation step, you need to prepare a complete set of sales materials, product data sheets, presentations (sometimes different ones for different groups inside a company), price lists, and so on. But unlike material you will produce later on in the company's life, this is all “preliminary,” all subject to change, produced in low volume at low cost. You just completed the first step in writing this material by coming up with your value proposition. You'll use it as the central theme in most of your sales materials.

Before any material is developed, figure out what sales material you need. Instead of randomly writing product specs and presentations, it's helpful to develop a “collateral plan,” a list of all the literature you will put in front of a customer in different phases of the selling process (see Table 4.1 for an example of a business-to-business collateral plan).

Table 4.1 Example of a Business-to-Business, Direct Sales Collateral Plan

| Awareness | Interest | Consideration | Sales | |

| Earlyvangelist Buyers | Corporate website Brochure | General sales presentation(s) | Tailor presentations to each customer | Contacts |

| Solution data sheets | White paper on business issue | Analyst report on business problem | Price list | |

| Influential bloggers | Product Presskit | |||

| Tech websites | Product brochure | ROI demonstration | ||

| Direct mail pieces | Viral marketing/ e-mail tools | Follow-up e-mail | ||

| Product data sheets | Pricing quote form | Thank-you note/e-mail | ||

| Technology Gatekeeper | Influential Bloggers | Tech presentation | Tech presentation on specific customer issues | Thank-you note |

| Tech websites | Tech white paper | Tech white paper | ||

| Analyst report on technical problem | Tech overview data sheets with architecture diagrams |

At my last company, E.piphany, I belatedly realized our positioning and strategy were a bit deficient; after presenting to the CIO we were thrown out of the fifth consecutive potential sale. In looking at our presentation I realized the slides were telling the CIO the same value proposition I had shared with his operating divisions: “You don't need your IT organization to give you information. Tell them to stuff it, and buy an E.piphany system.” Needless to say, sales were going to be difficult when we needed the backing of the CIO. We came up with a value proposition and presentation tailored to the CIO, the IT organization and technology gatekeepers.

In this example the sale was to a large corporation. The product was software used by employees but had to be installed and maintained by the IT department. Here the company must recognize there are two targets for its collateral: the earlyvangelist buyers and technology gatekeepers. If the sale is to a consumer, the collateral plan will focus on communications materials the sales channel will use. It can include shelf talkers, retail packaging, coupons, and so on. Regardless of the distribution channel or whether the product is sold to businesses or consumers, the collateral plan distinguishes with whom each collateral piece will be used and when in the sales process it will be used.

Don't worry about whether the collateral plan is perfect. It will change as you talk to customers, then change again as your customer base moves from visionary to mainstream. Test-drive all the collateral you produce, because what you write in the confines of an office often has little relevance in the field. Keep your collateral plan handy, as you'll be adding to it and updating it at each step of the Customer Development process.

It's helpful to realize visionary customers require different materials than mainstream customers. Visionary customers are first buying the vision and then the product. Therefore, make sure your materials are clear and detailed enough on the vision and benefits so your earlyvangelists can use your literature to sell your idea themselves, i.e., inside their own companies or to their friends and family. The Customer Development team and the founders should articulate the vision. For the product-specific details, Product Development should write the first draft. This way you can see if there are any surprises in what features the technical team would emphasize.

Remember, don't spend money on flashy design or large print runs in this phase. The only worthwhile investment is a good PowerPoint template and the two or three diagrams illustrating your key ideas.

Here are guidelines on some of the principal items that go into the collateral roadmap:

Websites at this stage of a startup should have clear information on the vision and problem you are solving, with enough detailed product information for the customer to want to engage in a conversation or actually make a purchase. This is a fine balance; you do not want a customer to have enough information to make a decision not to buy without you. Later you will use the same philosophy on your data sheets and product specs.

Your sales presentation should be an updated and combined version of the problem and product presentations used in Customer Discovery, with your value proposition added. However, very rarely does one presentation fit multiple audiences in a company or work across multiple industries. In Customer Discovery, you may have found you needed different presentations depending on the types of people who played a role in purchase decisions inside a company or different consumer audiences. Did you need a separate presentation for a technical audience? How about for senior management versus lower-level employees? How about for different companies in different industries? For consumer products, was there a different presentation based on demographics? Income? Geography?

Keep in mind at this stage the core audience is earlyvangelists, not mainstream customers. The sales presentation to visionary customers should cover a brief outline of the problem, possible solutions to the problem, your solution to the problem, and product details. It should run no more than 30 minutes.

Many products are too hard to understand without a demo. If a picture is worth a thousand words, a demonstration is probably worth a million. A caveat, though: Product Development teams in startups sometimes confuse “demo” with a working product. All the Customer Development team needs is a slide-based “dummy-demo” to illustrate the key points. I rarely have sold to earlyvangelists successfully without having one.

It's easy to confuse “product data sheets,” which detail product features and benefits, with “solution data sheets,” which address customer problems and big-picture solutions. If you are bringing a new product to an existing market, your focus will be on the product, so you should develop product data sheets. If you are creating a new market, the problem and solution data sheets are more appropriate. And if you are redefining a market, you need both.

In all cases you will likely need a technical overview with a distinctly deeper level of information for the other players in the sales cycle. As you begin to understand the sales process, issue-specific white papers may be necessary to address particular areas of interest or concern. Do these as you find they are necessary, but not before.

Listen and your customers will tell you what they need.

Especially in tight economic climates, one key piece of collateral customers ask for is a return on investment (ROI) white paper. This is a customer's fancy way of asking, “Show me how I can financially justify buying your product. Will it save me money in the long run?” Your earlyvangelist champions will usually have to make the case for your product before someone agrees to sign the check. For consumers the issue is the same. Just imagine kids trying to make the ROI issue for an Apple iPod. “I won't have to buy CDs and I'll pay for the songs out of my allowance.”

Price Lists, Contracts and Billing System

Hopefully, as you go through the Customer Validation step, some farsighted customers will ask, “How much is your product?” Even though you can give them the answer off the top of your head, you will need a price list, quote form, and contracts. Having these documents makes your small startup look like a real company. They also force you to put in writing your assumptions about product pricing, configurations, discounts, and terms. For consumer products, you will need a way to take early orders. You will need a billing system with credit card verification, online store, etc.

C. Get Ready to Sell: Develop a Preliminary Distribution Channel Plan

The Customer Development process helps you create a repeatable and scalable sales process and business model. The distribution channel plan and sales roadmap (developed in the next step) guide that effort.

Back in the Customer Discovery step, you refined your hypothesis about distribution channels using the information you learned in customer interviews. This phase assumes you have evaluated all the distribution channel alternatives and narrowed your distribution channel choices to one specific sales channel. Now you use that information to develop a preliminary channel plan.

A distribution channel plan comprises three elements. Initially, as you set up these elements, much of your thinking will be conjecture, based on the information you collected in Customer Discovery. However, as you move into the next phase of Customer Validation and start interacting with your selected distribution channel, you will refine your initial theories with facts and cold reality.

The elements used to build your distribution channel plan are:

- Channel “food chain” and responsibility

- Channel discount and financials

- Channel management

Channel “Food Chain” and Responsibility

Remember the channel brief you created in Customer Discovery? (Look back at Figure 3.5 for an example.) In that brief you spelled out your initial hypotheses about how your product would reach customers. Now it is time to further refine your distribution channel plan.

Start by drawing the “food chain” or tiers of the distribution channel. What's a food chain? For a distribution channel it is made up of the organizations between your company and your customer. The “food chain” describes what these organizations are and their relationships to you and each other.

For example, imagine you are setting up a book-publishing company. You will need to understand how to get books from your company to the book-buying customer. If you were selling directly to consumers from your own Web site, the “food chain” diagram for your publishing distribution channel might look something like Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2 Direct Book-Publishing Food Chain

However, selling through the traditional publishing distribution channel “food chain” would look like Figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3 Indirect Book-Publishing Food Chain

Regardless of the complexity of the diagram, your next step is to create a detailed description of each of the companies making up your channel's “food chain.”

Continuing with our book-publishing example, the descriptions would look like this.

- National wholesalers: Stock, pick, pack, ship and collect, then pay the publisher on orders received. They fulfill orders but do not create customer demand

- Distributors: Use their own sales force to sell to bookstore chains and independents. The distributor makes the sale; the bookstore orders from the wholesaler

- Retailers: This is where the customer sees and can purchase books

It is useful to create a visual representation of all the information you have assembled on the distribution channel (see Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4 Channel Responsibility Map

One mistake startups often make is assuming their channel partners invest in creating customer demand. For example, in Figure 4.4, it would be a mistake to think your book wholesaler does anything other than stock and ship books. The same is true for the distributor. They take orders from bookstores, and in some cases may promote your books to bookstores, but they do not bring customers into the store to buy your books.

A channel responsibility map allows you to diagram the relationships in a complex distribution channel. A written description of these responsibilities, much as you created for the “food chain,” should accompany the diagram. It helps everyone on the team understand why you are using the channel and what to expect from it.

Channel Discounts and Financials

Each tier in the distribution “food chain” costs your company money since each tier will charge a fee for its services. In most channels, these fees are calculated as a percentage of the “list” or retail price a consumer will pay. The next exercise helps ensure you understand how the money flows from the customer to you. First, calculate the discounts each channel tier requires. Continuing with our book-publishing example, Figure 4.5 details these.

Figure 4.5 Channel Discounts

As you can see, a book retailing for $20 would net our publishing company $7 after everyone in the channel took their cut. Out of this $7 the publisher must pay the author a royalty, market the book, pay for the printing and binding, contribute to overhead, and realize a profit.

Channel discounts are only the first step in examining how money flows in a complex distribution channel. Each tier or level of the channel has some unique financial relationship with the publisher. For example, most regular sales to a bookstore are on a consignment basis. This means unsold books can be heading back to you. Why is this a problem? A mistake companies frequently make when they use a tiered distribution channel is to record the sale to the tier closest to them (in this case the national wholesaler) as revenue. An order from a channel partner does not mean an end customer bought the product, just the channel partner hopes and believes they will. It's like a supermarket ordering a new product to put on the grocery shelf. It isn't really sold until someone pushing their cart down the aisle takes it off the shelf, pays for it and takes it home.

If you have a channel returns policy that allows for any kind of stock rotation, you must make allowances in your accounts for a proportion of that sale to be returned. Your channel financial plan should include a description of all the financial relationships among each of the channel tiers (see Figure 4.6).

Figure 4.6 Channel Financials

Your ability to manage your distribution channel will directly affect your ability to deliver on your revenue plan. Although every company's goal is a well-managed and carefully selected channel, failure to select the right channel or to control the channel often results in miserable sales revenue and unanticipated channel costs. You will need a plan to monitor and control your channel's distribution activities, particularly inventory levels. In a direct sales channel, it's straightforward: no goods leave the company until there is a customer order. However, in an indirect channel the biggest risk is not knowing how much end-user demand exists. Why? Looking at any of the channel “food chain” diagrams, you can see your company will have a direct relationship with only the tier of distribution closest to your company. You will be dependent on reports, often months out of date, to know how much of your product has “sold through” the channel—in other words, how much has been purchased by customers. Another risk is the temptation in an indirect channel to “stuff” the channel. Stuffing means getting a tier of the channel to accept more product on consignment than sales forecasts can reasonably have expected the channel to sell through. For companies that recognize revenue on sales into the channel, this can provide a temporary inflation of sales followed by a debacle later. All these potential issues need to be documented and discussed in the channel management plan to avoid costly future surprises.

D. Get Ready to Sell: Develop a Preliminary Sales Roadmap

Developing a sales roadmap is all about finding the right path through unknown and dangerous terrain. A fog of uncertainty hangs over the early steps of the sales journey. In Customer Validation, you pierce that fog by gathering sufficient information to illuminate how to proceed, one discrete step at a time, then assemble that information into a coherent picture of the right path to take.

Your goal is to determine who your true customers are and how they will purchase your product. You're ready to begin building a sales team only when you completely understand the process that transforms a prospect into a purchaser and know you can sell the product at a price that supports your business model. With the sales roadmap in their hands, your sales force will be able to focus on actual sales instead of the hit-and-miss experimentation you will experience as you move through Customer Validation.

The complexity of your company's sales roadmap will depend on a number of things: the size of your customer base, budget, the price of your product, the industry in which you are selling, and the distribution channel you've selected. Sales to Intel or Toys R Us, for example, will require a more involved process than sales to local florists or pet stores. Creating a roadmap and validating it may seem like an enormous investment of time and energy, and a huge distraction from the challenges of building a business. But it could make the difference between success and failure. Better to know how to sell your product while your company is lean and small than try to figure it out as you are burning through cash sending your sales and marketing departments out.

The sales roadmap comprises four elements. As with the distribution channel plan, much of your initial thinking here will be conjecture based on the information you collected in Customer Discovery. However, as you move into the next phase where you actually sell your product, you will refine your initial theories with facts.

The elements used to build your sales roadmap are:

- Organization and influence maps

- Customer access map

- Sales strategy

- Implementation plan

Organization and Influence Maps

Remember the organization and influence map briefs you created in Customer Discovery? Pull them off the wall and study your findings. By now your early hypotheses have been modified to reflect the reality you encountered as you spoke with potential customers. Use this information to develop a working model of the purchase process for your target customer. Take a closer look at your notes from your encounters with possible earlyvangelists. You might also want to bring in customer information from other sources such as a company's annual report, Hoovers, Dun & Bradstreet or press articles.

The E.piphany sales cycle is a good example of how an influence map is derived. Given E.piphany's software cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, an executive must have had a significant pain, recognized it was a pain, and have been committed to making the pain go away if E.piphany was to get a deal. Second, selling our product required “top-down selling.” Working your way up from low levels is not only more difficult but much less likely to end in success. Third, E.piphany changed the status quo: Our products impacted many people and many organizations. Typically, those who oppose change or who have a large stake in the status quo will oppose software others regard as progress.

The bad news: Multiple “Yes” votes were required to get an E.piphany order. Other enterprise software like sales automation or customer support just needed support from a single key executive or from a single user community to drive a sale to closure. With those packages IT personnel generally had input in the selection of a software package, but the users enjoyed substantial power in the decision-making process. An E.piphany sale was different. IT, though not the driver, was an active participant in the decision-making process and often enjoyed veto power. Likewise, our experience showed we needed to sell “high” and “wide” on both the user and technical sides of an account. After getting thrown out of multiple accounts we built a simple two-by-two matrix to show where we needed to get support and approval from each of our prospect accounts.

Figure 4.7 Support and Approval Matrix

This matrix basically said even with a visionary supporting the purchase of the E.piphany product, we had to sell to four constituencies before we could close an order.

Without support on the operational side and “approval” by the IT technical team, we couldn't get a deal. If the IT organization became determined to derail an E.piphany deal, it would probably succeed. This insight was a big deal. It was one of the many “aha's” that made E.piphany successful. And it happened because we had failed, and a founder was part of that failure and spent time understanding the solution.

Our early sales efforts fell short largely because we ignored the fact that selling E.piphany into the enterprise was different from the sale of other enterprise products. The most glaring oversight was our failure to enlist the support of the IT organization. In our sales calls we had found it was easier to get people on the operational side excited about our products and win their support than it was to get IT professionals to buy into a packaged data warehouse and a suite of applications to serve the needs of marketing. In some cases we had taken prospects on the operational side at their word when they indicated they could make IT “fall into line” should they need to. In other cases, we skipped some needed steps and assumed several enthusiastic users could do our deal. Rarely did this prove to be true.

We took that sales failure and success data and put it together into an Influence Map. Remember by this time we had established that 1) we needed to win the support of four groups to get a deal done; 2) IT would probably be harder to win over than the users; and 3) low-level IT personnel would oppose us. So how should we proceed? The Influence Map in Figure 4.7a illustrates the execution strategy for E.piphany sales. It diagrams the players, and maps the order in which they need to be convinced and sold. Each step leveraged strengths from the step before, using momentum from groups that liked our company and products to overcome objections from groups that did not. The corollary was if we tried to shortcut the process and skip a sales stage, more often that not we would lose the sale.

Once understood, the Influence Map set the execution strategy for sales. Call on: 1) high-level operational executives (VPs, divisional GMs, etc.) first. Use that relationship as an introduction to 2) high-level technical executive (CIO or divisional IT executive), then 3) meet the operational organizations end users (the people who will use our product), and finally, 4) use that groundswell of support to present to, educate and eliminate objections from the Corporate or Division IT staff.

Figure 4.7a Example of an Influence Map

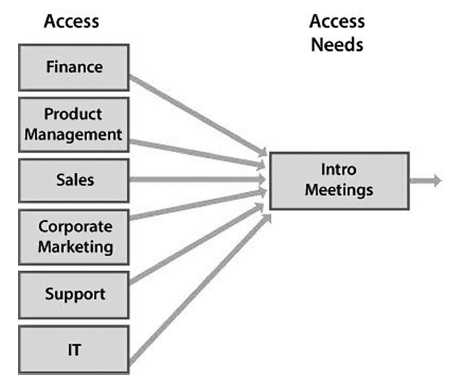

Now turn your attention to answering the proverbial sales question: How do you get your foot in the door? For a corporation, depending on the size of the organization you are approaching you may need to move through different layers or departments before you can set up meetings with the people you identified in the organization and influence maps. As you begin to develop an access map for the companies you are targeting, you may draw a lot of blanks. But once you begin to call on actual customers, you will be able to add information and perceive patterns. Figure 4.8 illustrates an access map in a corporate account.

Figure 4.8 Example of an Access Map

For consumer sales, finding the right entry to early customers can be equally difficult. Rather than making random calls, think of organizations and special-interest groups you can get to inexpensively. Can you reach customers through organizations they belong to, such as the PTA, book clubs, antique car clubs? Are there Web-based groups that may be interested?

Lay your corporate/consumer organization map and influence map side by side. For a corporate sale, your challenge is to move beyond the names and titles of the people you will call on to develop a strategy of how you will approach them. For example, imagine you are developing a sales strategy for InLook, which has created a software product for CFOs. In this phase, as you begin to develop a sales strategy, here are some questions to consider:

- At what level do you enter the account? Do you sell high to executives? Or low to the operational staff?

- How many people on the organizational map need to say yes for a sale?

- Does each department perceive the customer problem in the same way?

- In what order do you need to call on these people? What is the script for each?

- What step can derail the entire sale?

Similarly, if you were trying to reach twenty-somethings with a new consumer product the questions might be:

- Do you need access to a specific demographic segment? Do you sell to college students? Parents of children? Families?

- How many people need to say yes for a sale? Is this an individual sale or family decision?

- If this sale requires multiple members of a family or group to agree, in what order do you need to call on these people? What is the script for each?

- What step can derail the entire sale?

Again, as you move out into the marketplace to sell your product, you will learn what works or not. As predictable patterns emerge, your strategy will become clear.

You've made the sale, the visionary customer has said thumbs up. Don't open the champagne quite yet. Much can happen between when the decision-maker agrees to make a purchase and you receive the check. The goal of the implementation plan is to write down all the things left to happen before the sale is finalized and the product delivered, and to determine who will follow up to manage them. For example:

- Does the CFO and or CEO need to approve the sale?

- Does the board need to approve the sale?

- Does Mom or Dad need to approve the sale?

- Does the customer need to get a loan to finance the sale?

- Do other systems/components from other vendors need to be working first?

E. Get Ready to Sell: Hire a Sales Closer

In most startups it's likely the founding team is product-oriented and does not include a sales professional. While the founders can get quite far in finding visionary customers, they usually have no skill or experience turning that relationship into the first order. Now that you are about to sell, a key question is, does someone on the founding team have experience closing deals? Does the team have a world-class set of customer contacts? Would you bet the company on the founders’ ability to close the first sales? If not, hire a sales closer.

A sales closer is not a VP of Sales who wants to immediately build and manage a large sales organization. A sales closer is someone with a great Rolodex in the market you are selling into. Good sales closers are aggressive, want a great compensation package for success, and have no interest in building a sales organization. Typically, they are experienced startup salespeople who love closing deals and aren't yet ready to retire behind a desk.

The founding team and sales closer make up the core of the Customer Development team. It becomes their job to learn and discover enough information to build the sales and channel roadmaps. You may want to go once around the Customer Validation loop without a sales closer. Then when you understand where the lack of sales skills is stunting progress, hire the closer. But while the sales closer will be an integral part of Customer Validation, the founders and CEO still need to lead the process. Sales closers are invaluable in setting up meetings, pushing for follow-up meetings, and closing the deal. However, having a sales closer is not a substitute for getting founders to personally gather customer feedback.

F. Get Ready to Sell: Align Your Executives

Selling a product implies a contractual commitment between the company and a customer on product features and delivery dates. Before you leave the building to sell, the Customer Development and Product Development teams need to be in violent agreement about all deliverables and commitments the company will make. So it's essential executives review and agree on the following:

- Engineering schedule, product deliverables and philosophy

- Sales collateral

- Engineering's role in selling, installation, and post-sales support

Engineering Schedule, Product Deliverables, and Philosophy

In order to sell to visionary customers as part of Customer Validation, the Customer Development team is about to commit to “ship dates” to these customers. Now is the time to verify that your Product Development team is absolutely sure you can deliver a functional product for your early visionary sales. Missing your ship dates for these first customers means more than simply missing a delivery date would mean for a large, established company. If your dates slip badly, or if you have continual slippages, your earlyvangelists’ positions in their companies (or in the case of a consumer product, with their friends and families) will weaken, and ultimately you will lose their support. Your product can acquire a taint of vaporware, an always announced but never shipping product. Avoid surprises. Look at the scheduled dates for key Product Development milestones, compare them to the actual delivery dates, and take the ratio to compute a “slip factor.” Then apply that number to any dates Customer Development receives from Product Development to derive the dates that will be promised to customers.

Even harder than guaranteeing the ship date of the first product is getting a Product Development team struggling with first product release to understand the value of articulating what will be in the next three releases. As a group you came up with the first pass of this forecast in Customer Discovery Phase 1. Now your Customer Development team needs to know whether the engineering release schedule you tentatively proposed then is still valid. Both the Product and Customer Development teams need to ensure all changes from Customer Discovery Phases 3 and 4 have been integrated into the product spec and then agree on the committed features by release.

In exchange for this look into the future, both teams agree on a “good enough” philosophy for deliverables and schedule. The goal is to get earlyvangelists an incomplete, barely good enough product in the first release. The visionary customers can help you understand the minimum features needed to make the first release a functional product. This means Product Development should not strive for architectural purity or perfection in the first release. Instead, the goal for Product Development should be to build the product incrementally and iteratively—getting it out the door and quickly revising it in response to customer feedback. The purpose is not “first mover advantage” (there is none), or a non-paying alpha or beta test, but to get customer input on a product that's been paid for.

There are two reasons for this “good enough” minimum feature set philosophy. First, regardless of what the users say, it's very hard to be 100 percent certain what's important to them until they have a first release in their hands. You may have talked to everyone in Customer Discovery and interviewed earlyvangelists but they may not know what's important until they use the product. Later, you may find when the product is used this important feature only gets exercised every six months. The minor feature you ignored? They use it six times a day. The second reason for this “good enough” philosophy is this first product is for earlyvangelists, not mainstream users who often have different expectations of what features are important.

This “ship it before it's elegant and pristine” concept is hard for some Product Development teams to grasp. Its implementation is even harder. There is a fine line between shipping a “good enough” product with a minimum feature set and an unusable product customers call junk.

There is no greater source of acrimony in a startup than finding out the company has sold something Product Development says it never committed to build. Therefore, it's essential for both teams to review and agree on the facts in all the sales collateral. To this end, Product Development reads and signs off on all Web pages, presentations, data sheets, white papers, and so on. This doesn't mean Product Development gets to approve or reject the collateral. It means they get to fact-check it and point out any discrepancies with reality.

Engineering's Role in Sales, Installation, and Post-Sales Support

In a company with products already shipping, the demarcation between Product Development and sales, installation, and customer support is clear. In a startup, these lines need to blur. Remember, you have agreed to make Product Development's life easier in two substantive areas. First, Customer Development's job is to find a market for the product as spec'd and to ask for more features only if a market cannot be found. Second, Customer Development has agreed the first release of the product will be incomplete, and the early visionary customers will help everyone understand the next release. In exchange, a critical feature of the Customer Development model is the agreement that Product Development will actively help with sales, installation, and support. This means the technical visionary and head of technical execution commit to sales calls and key engineers commit to helping answer detailed questions from customers. There is no substitute for direct, hands-on experience in “becoming the customer” for Engineering to make a better product. In the Customer Development model, 10 percent of Product Development's time is spent out in the field selling, installing, and providing post-sales support.

Keep in mind this notion of an “incomplete first release” with a minimum feature set is a walk on the knife of adroit execution, particularly in consumer markets. The goal is to get the product to market as early as possible to receive customer feedback, but not to distribute the product so widely that its limited feature set becomes etched in the customer's mind as the finished product.

G. Get Ready to Sell: Formalize Your Advisory Boards

In some cases you may have asked for advisors’ help on an informal basis in Customer Discovery. In this phase, you formally engage them. There are no hard-and-fast rules for how large the advisory board should be. There can be as many people on the board as you want. Think strategically, not tactically, about the sphere of influence and reach of advisors. Recruit only the advisors you need now, but make exceptions for “brand names” and “influencers” you want to cultivate. Don't believe you need a formal advisory board meeting. All you want right now is time and access.

Begin by assembling an advisory board roadmap, much like the collateral roadmap you developed earlier. As shown in Table 4.2, this roadmap is an organized list of all the key advisors needed.

In this example the roadmap differentiates how each advisor will be used (technical, business, customer, industry and marketing). Product Development may need technical advisors on the “Technical Advisory Board” as early as Phase 1 of Customer Discovery. The technical advisory board is staffed for technical advice and points to technical talent. These advisors may be from academia or industry. As the company begins to sell product, these advisors are used as technical references for customers.

Table 4.2 Advisory Board Roles

| Technical | Business | Customer | Industry | Sales/Marketing | |

| Why | Product Development advice, validation, recruiting help. | Business strategy & Company Building advice. | Product advice & as potential customers. Later as customer conscience & as references. | Bringing credibility to your specific market or technology through domain expertise. | Counsel to help sort out sales, PR, press, and demand ceation issues. |

| Who | Brand name technical luminaries for show, plus others with insight into the problems you are solving and are OK with getting their hands dirty. | Grizzled veterans who have built startups before. Key criteria: you trust their judgment and will listen to them. | People who will make great customers, who have good product instincts, and/or who are part of a customer network. | Visible name brands with customer and press credibility. May also be customers. | Experienced startup marketers who know how to create a market, not just a brand. |

| When | Day one of company founding and continuing through first customer ship. | Day one of company founding & ongoing. | In Customer Discovery. Identify in phase 1, begin inviting in phases 2 & 3. | In Customer Validation. Identify in phase1, begin to invite in phase 3. | In Customer Creation. Need diminishes after Company Building. |

| Where | One-on-one meetings with Product Developoment staff at company. | Late-night phone calls, panicked visits to their home or office. | Phone calls for insight & 1-on-1 meetings with business and Customer Development staff at company. | Phone calls for insight & 1-on-1 meetings with business and Customer Development staff at company. | One-on-one meetings and phone calls with marketing and sales staff. |

| How Many | As many as needed. | No more than two or three at a time. | As many as needed. | No more than two per industry. | One for sales, one for marketing. |

Ensure key potential customers are on the “Customer Advisory Board.” These are people you met in Customer Discovery who can advise you about product/market fit from the customer's perspective. I always tell these advisors, “I want you on my advisory board so I can learn how to build a product you will buy. We both fail if I can't.” They will serve as a customer conscience for the product, and later some of them will be great references for other customers. Use them for insight and one-on-one meetings with the business and Customer Development staff at your company.

Distinct from customer advisors is an industry advisory board. These domain experts are visible name brands who bring credibility to your specific market or technology. They may also be customers, but they are typically used to create customer and press credibility.

Finally, you may want to have some general business advice from a “been there, done that” CEO. Executives who can give you practical advice are more than likely those who have run their own startups. Sales and marketing advisors are the perfect foils for testing what you've learned in Customer Discovery, Validation and Creation.

The number of advisors for each domain will vary with circumstances, but there are some rules of thumb. Both sales and marketing advisors tend to have large egos. I found I could only manage one of those at a time. Industry advisors like to think of themselves as “the” pundit for a particular industry. Have two give you opinions (but don't have them show up on the same day). Business advisors are much like marketing advisors but usually have some expertise in different stages of the company. I always kept a few on hand to get me smarter. Finally, our Product Development team could never get enough technical advisors. They would come in and get us smarter about specific technical issues. The same was true for the customer advisors. We made sure we learned something new every time they came by.

Phase 2: Sell to Visionary Customers

In Customer Discovery you contacted customers twice, first to understand how they work and the problems they have, and then to present the product and get their reaction to it. Now, in Phase 2 of Customer Validation, the rubber meets the road. Your task is to see whether you truly have product/market fit and can sell early visionary customers before your product is shipping. Why? Your ability to sell your startup's product will validate whether all your assumptions about your customers and your business model are correct. Do you understand customers and their needs? Do customers value your product features? Are you missing any critical ones? Do you understand your sales channel? Do you understand the purchasing and approval processes inside a customer's company?

Is your pricing right? Do you have a valid sales roadmap you can use to scale the sales team? You want the answers as early as possible, before change is costly. Waiting until the product is completely developed and your sales and marketing departments are staffed is a fatal flaw of the Product Development model.

OK, so you want customer feedback early. But why try to sell the product now? Why not simply give it away to early brand-name customers to get them on the bandwagon? Why aren't you giving away product so Engineering can have alpha and beta sites? This question has bedeviled startups since time immemorial. The answer is: Giveaways do not prove customers will buy your product. The only valid way to test your assumptions is to sell the product.

Some readers may wonder what the role of the Customer Development team is in alpha and beta testing. The answer is a little bewildering to those who have done startups before: There is none. Alpha and beta tests are legitimate activities of the Product Development organization and part of the Product Development process. When the product is in an intermediate stage of development, good Product Development teams want to find real customers to test the product's features, functionality, and stability. For an alpha or beta test to succeed, the customer must be willing to live with an unstable and unfinished product, and to cheerfully document its problems. Good alpha and beta customers are likely found in advanced development, engineering, or non-mainstream parts of a company or market. Therefore, alpha and beta testing are Product Development functions that belong to engineering. They are about validating the product technically, not the market.

Since alpha and beta testing marks the first times a product leaves the company, salespeople have treated alpha and beta sites as opportunities to consummate the first sale of the product. This is a mistake, because it results in a sales process that focuses on Product Development as its model (bad) rather than on a Customer Development model (good). The reality is that testing an unfinished product for Engineering and testing a customer's willingness to buy an unfinished product are separate, unrelated functions. Customer Validation is not about having customers pay for products that are engineering tests. It's about validating the entire market and business model. While the Customer Development team may assist in finding customers for the Product Development organization to use in alpha and beta testing, the testing itself is not part of Customer Development. Companies that understand this can give away alpha and beta products for engineering test without compromising or confusing it with Customer Development.

Alpha and beta testers can be influential as recommenders in the sales process. Just don't confuse them with customers. It's important to inculcate a cultural norm in your company that you use the word “customers” only for people who pay money for your product.

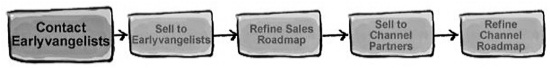

Again: The way you validate your business model and whether you truly have product/market fit is by selling it to customers. Accordingly, in this phase you will:

- Contact visionary customers

- Refine and validate your sales roadmap as you persuade three to five customers to purchase the product

- Refine and validate the distribution channel plan by getting orders from channel and service partners

A. Sell to Visionary Customers: Contact Visionary Customers

The biggest challenge in this phase of Customer Validation is to spend your time with true visionary customers, not mainstream customers. Remember visionary customers not only recognize they have a problem, they're so motivated to do something about it that they have tried homegrown solutions and have budgeted money for a solution. Were there any key characteristics of visionary customers you saw in Customer Discovery? Would any of those help you identify where you can find more prospects? Use the same techniques you used in Customer Discovery: Generate a customer list, an introductory email, and a reference story/script. Even with all your preparation, assume one out of 20 prospects you call on will engage in the sales process. In other words, be prepared for 95 percent to say no. That's OK; you only need the other 5 percent. Of those, depending on the economic climate, 1 out of 3 to 1 out of 5 will actually close when you get around to selling. That's a lot of sales calls. (That's why your company is a startup.) The good news is by this phase you have a sales closer on board to handle the tedium of making contact and arranging meetings.

It is helpful at this point to distinguish earlyvangelists from other major categories of customers: early evaluators, scalable customers, and mainstream customers. Table 4.3 describes the differences among these groups in terms of their motivation, pricing, and decision power; the competition you face in selling to them; and the risks in selling to them.

Table 4.3 Four Types of Customers

| Early Evaluators | Earlyvangelists | Scalable Customers | Mainstream Customers | |

| Motivation | Technology evaluation | Vision-match. Understand they have a problem and have visualized a solution you have matched. | Practicality. Interested in a product that can solve an understood problem now. | Want to buy the standard, need the “whole product” delivered. |

| Pricing | Free | Using their pain threshold, you get to make up the list price and then give them a hefty discount. | Published list price and hard negotiating. | Published list price and harder negotiating. |

| Decision Power | Can OK a free purchase | May be able to OK a unilateral purchase. Usually can expedite a purchase. Internal cheerleader for a sale. | Buy-in needed from all levels. Standard sales process. May be able to avoid competitive bake-off. | Buy-in needed from all levels. Standard sales process. Competitive bake-off and/or RFP. |

Think of early evaluators as a group of tire kickers you want to avoid. Every major corporation has these groups. When they show interest in a product, startups tend to confuse them with paying customers.

Earlyvangelists have already visualized a solution – something like the one you are offering. They are your partners in this sales process. They will do their own rationalization of missing features for you as long as you don't embarrass or abandon them.

Scalable customers may be earlyvangelists as well, but they tend follow visionaries. Instead of buying on a vision, they buy for practical reasons. These will be your target customers in six months. They are still more aggressive purchasers of new products than mainstream customers.

Finally, mainstream customers are looking for the whole product and essentially need an off-the-shelf, no-risk solution. They will be your customers in one to two years.

B. Sell to Visionary Customers: Refine and Validate the Sales Roadmap

Can you sell three to five early visionary customers before your product is shipping? The key to selling a product on just a spec is finding earlyvangelists who are high-level executives, decision-makers and risk-takers. The earlyvangelists you are looking for now are those who could deploy and use the product. You don't need many of them at this point. Why? Because the goal is not to generate a whole lot of revenue (even though you will be asking for near list price); the goal is to validate your sales roadmap.

Let's return for a minute to Chip Stevens, the InLook CEO who left his office to develop a sales roadmap. Figure 4.9 illustrates the organizational map Chip developed for InLook's Snapshot product.

Figure 4.9 Example of an Organizational Map

InLook's customer is the CFO, while the key influencers are the controller and the VP of financial operations. But in a series of companies, InLook discovered internal competition from IT, which championed its own homegrown financial tools. Additionally, InLook has learned many managers in the sales department believe financial modeling is their “turf” and have built a sales analyst group to provide this function. To be successful, InLook needs to eliminate opposition from sales and IT by educating the VP of Sales and the CIO.

Chip developed a sales strategy recognizing these competing internal interests and built on the interplay between purchasers and influencers in large corporate accounts (see Figure 4.10).

Figure 4.10 Example of a Selling Strategy

Chip found he could gain access by meeting with and acquiring an executive sponsor—either the CFO, controller or VP of finance if the executive felt an acute need for InLook's software solution and had the vision and budget for the project. In addition, the executive sponsor would greatly influence the end users who generally want something their boss wants. Finally, the executive sponsor could represent the production solution to the CIO and help eliminate objections from and gain the support of the IT organization. Although a company's IT organization would not initiate a project to solve the CFO's problem, IT was a critical influencer in the sales process. So next InLook needed to meet with a company's IT executive and win his approval. Chip had also learned IT's attitude was a useful way to qualify accounts. If InLook could not win the IT support early in the sales cycle, it needed to think long and hard about investing more sales time and resources in that account.

The third move in InLook's strategy focused on finance managers who would use the product. They were generally enthusiastic about the software since it made their lives easier. Finally, InLook needed to engage the IT technical staff. If InLook executed properly on steps 1 through 3, the chances of getting approval from the technical staff were greatly enhanced, and not by accident: InLook has them surrounded. The users want the product, the finance executive wants it, and the head of IT has granted approval. (See the sales roadmap in Figure 4.11.)

Figure 4.11 Example of a Sales Roadmap