1

INTRODUCTION: Why Procurement, and Why Now?

What Follows Is a True Story

Many years ago, I was at a cocktail party hosted for expats in London, with my wife. Many of those present were from the big New York investment banks. At one point, I started chatting with one of these individuals.

“So, what do you do?” he asked.

“I'm a consultant.” I replied.

“Consulting in which field?” he asked.

“Procurement” I replied, at which point he looked at me with an expression of disgust and said, “Excuse me while my eyes glaze over,” then turned around to signal that the conversation was over.

Now, that's very rude behaviour, but that's not the point. The point is that Procurement has such a poor image that it's not even deemed worthy of a conversation by those who consider themselves to be at the top of the business food chain. Procurement is just not exciting, and it's certainly not sexy.

Well, how exciting does it have to be? How about having the potential of increasing your EBITDA by a third? How about having the resilience to keep your supply chain up and running during a global pandemic? Procurement is an enormous profitability lever, and it should be a core competence—especially in modern times, in which companies accomplish more and more through outsourced relationships.

Yet in the majority of companies, Procurement is far from optimized, and there is a massive prize to be had if we could only do a better job. Since Procurement represents between 50 and 80% of a company's costs depending on the industry, and since most savings extracted from that spend flow straight to the bottom line, then I'd say that makes it interesting!

In this chapter, we will set the scene for the book, by examining why there is an opportunity in Procurement, what the size of the prize could look like, and why many companies have failed to cash in on the promise to date. At the end of the chapter, we provide some background to the book, along with an overview of what you can expect from the remaining chapters.

Let's now step right back and examine why there is an opportunity associated with Procurement. There are, in essence, two reasons: (i) Procurement is typically a company's largest cost bucket, and (ii) in most companies, that cost bucket is not optimized. Let's look at each in turn.

Procurement Is a Company's Number One Cost, Making It a Huge Profit Lever

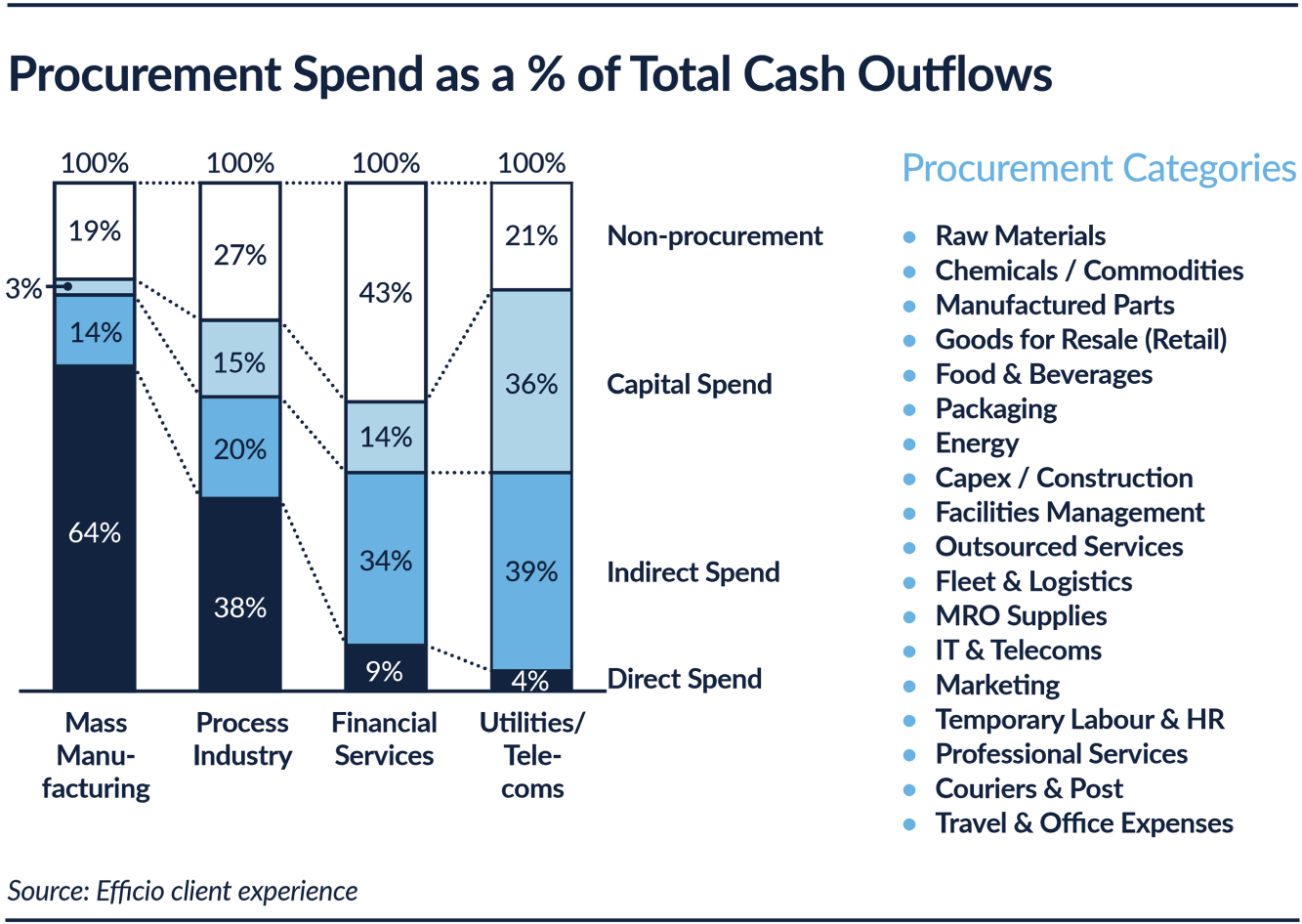

Procurement represents between 50 and 80% of a company's total costs, depending on the industry. That feels like a big number, but that's just because external spend is not usually counted in one place. A company's external spend contains so many things (from office supplies to raw materials to factory maintenance services to energy, fleet, marketing, and IT), fragmented across so many business units, geographies and budget lines, that it's rarely seen in aggregate (see Figure 1.1).

OK, so the spend is big, but how big is the opportunity? In many companies that have not yet optimized Procurement, it can be very significant. Figure 1.1 looks at a typical manufacturing company, with revenues indexed to 100. Well, if you simply subtract from that 100 your EBIT (or add back in your losses), then take out depreciation and your whole salaries and wages bill, then what's left of the 100 is by definition externally procured. In this example (see Figure 1.2), that amounts to 60…60% of the revenue!

Figure 1.1 Procurement Spend as a Percentage of Total Cash Outflows

The next question is, how much can you take out of that 60? Well, a common mistake is to assume that “10% should be possible.” Maybe 10% is possible, but not on the whole 60 of spend, at least not in the medium term, because some spends will be non-addressable or locked in, and there is always a “tail” of specialist one-off suppliers. These non-addressable spends can be significant, so it's safe to assume that maybe 60% of the 60 is addressable in the medium term. If your organization is global, you may also have a collection of very small, remote geographies whose spend may be too small to merit addressing in the medium term, which could reduce the 60% further.

In terms of how much can be saved, this of course varies by category and by company. But, long story short, a company that has not optimized Procurement, can look to take roughly 10% out of its addressable spend. In the worked example in Figure 1.2, that equates to a saving of 3.6 from an addressable spend of 36 (60% of 60). Given that the company had an EBIT of 10 going in, then that's a 36% uplift on a 10% margin. And that's before you factor in any Capex savings (which of course hit EBIT only indirectly).

Figure 1.2 Procurement's EBIT Impact

The beauty of Procurement is that this opportunity (or your spend) is spread across some 40 or so spend categories. This comprises a very diverse set of things (from Office Supplies to Logistics Providers to Raw Materials to Components…), each with totally different suppliers and its own internal stakeholders. Since a Procurement effort is best structured around category teams (see Chapter 3: Sourcing Execution), then this creates a natural portfolio effect across your target—one category may fail, but another will over-deliver. This portfolio effect is critical in Procurement economics, in that it significantly mitigates the risk of non-delivery.

At the end of the day, it would be difficult to find opportunities with as much potential impact on EBITDA as Procurement, without the need to reduce headcount, close offices, or make major investments. So, at least on paper, the Procurement opportunity is significant.

That's all very well in theory. But what about in practice? How do I know that the 10% is actually there? Why is there an opportunity in this cost base? Answer: Because in many companies, Procurement is not optimized. Let's examine why that is the case.

Why Is Procurement Not Optimized?

The opportunity in Procurement exists because in many companies, Procurement is not optimized. There are a number of reasons for this:

- Procurement comes from an administrative background, and oftenlacks the remit to take a strategic or proactive approach.

- Procurement therefore doesn't have the right cross-functional operating model, and sometimes adopts unhelpful mindsets.

- This results in an under-investment in people and tools, creating a vicious cycle of under-performance and under-investment.

- The end result is a spend base that's not optimized—not aggregated across locations, and with inconsistent specifications and dated supplier relationships.

Let's explore some of these points in a little more detail.

Remit

The point regarding remit is fundamental: it asks the question, what is expected of Procurement? Unfortunately, many Procurement functions do not have a remit to “work with the budget holders to proactively optimize their cost base using the full suite of supply and demand levers.” Rather, the expectation is that Procurement will come in at the last minute to negotiate and execute the contract. That remit will allow Procurement to achieve maybe 25% of its potential. And therein lies the problem, or the opportunity…the Procurement function is probably doing a good job—but based on an overly narrow remit.

The root of this problem is that Procurement's history lies in administration. The function started life as a mechanism to legally procure goods and services on behalf of the business and is therefore seen as a support function—one that ensures that supplier contracts get signed and materials show up. Over time, Procurement teams have been built on these administrative foundations as their functions have evolved. In many organizations, the budget holder actually makes most of the decisions—from deciding what part is needed, to deciding to go with the OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturer) part to, very often, talking to the OEM and agreeing to a price. Only then is Procurement brought in, to close the deal, sign the contract, and order the part. And that's the typical remit…which ensures that probably 80% of the cost is already locked in by the time Procurement comes to the table, thereby severely constraining Procurement's potential contribution from the get-go.

Given this restrictive remit, it comes as no surprise then, that Procurement often hasn't developed anywhere near the right cross-functional operating model: see Chapter 5: Operating Model, for a more detailed discussion of this. To make matters worse, in the absence of a clear role, buyers can sometimes adopt unhelpful mindsets. Instead of adopting a service mentality along the lines of “I am here to help you with your spend,” there is often a mindset based on perceived authority.

Mindset

We've seen unhelpful Procurement mindsets at countless companies; the most common ones I would describe as “the policeman” and the “Procurement professional.”

The policeman is a historical legacy. Most Procurement organizations were set up to help get control of external spend, with a focus on purchase orders and necessary draconian policies of “if it doesn't go through Procurement, it doesn't go through.” This has set them up for decades-long fights with stakeholders; fights in which Procurement is the policeman, chasing down the non-compliant stakeholders (sounds like a Procurement Blade Runner!).

As a result, many Procurement teams have cast themselves (often unintentionally) in a “policeman” capacity vis-à-vis “the spenders.” Nowadays, this legacy mindset really doesn't wash with sophisticated and intelligent stakeholders in functions such as Engineering, Manufacturing, Technology, or Marketing. In fact, the opposite is required—a collaborative, open, intelligent approach, not a “you have to go through Procurement” approach. To this day, I see vestiges of this mindset in Procurement teams, and it's not helping the cause.

The other thing that doesn't help is when Procurement positions itself as too much of a profession. Rather than credentializing Procurement, this can sometimes create a barrier—the message here being, “We have techniques that you guys don't understand” and “We're better negotiators than you are.” I've found that the strongest Procurement people are the ones who never feel the need to mention their professional skills. They just relate well to the stakeholder, and they do good work.

These somewhat dysfunctional mindsets, when coupled with an already weak remit, can act to severely undermine Procurement's potential impact.

Vicious Cycle…and Opportunity

The lack of remit, the lack of cross-functional engagement, and, ultimately, the lack of impact of Procurement, have in turn led to a vicious cycle of under-investment in the function. In many organizations, Procurement is therefore seen as a strictly back office function that's largely ignored by senior management.

But what this historical neglect brings with it is an enormous opportunity. Most of the external spend will be ripe for Strategic Sourcing: the spend will not have been leveraged or aggregated across countries or manufacturing plants. The specifications will be outdated, “what Engineering has always used;” and there will be longstanding supplier relationships that are never tendered, ready to be shaken up with a bit of competition. In short, significant savings potential will exist across the entire third party spend.

But of course, to capture that potential, you need to work backwards and fix the remit, fix the resources available to Procurement, and fix the investment level in Procurement. We need to find a better way. Well, the good news is, that better way has been around for over 30 years.

The Birth of Strategic Sourcing—Dawn of a New Era…or Not?

Back in the 1980s, a new way emerged for Procurement when General Motors placed its engineers and buyers in cross-functional teams and told them to “go to town” on components, changing the specifications, changing the drawings, bidding GM's combined demands in the market globally—and it worked magically and gave birth to “Global Sourcing.” This was soon replaced by “Strategic Sourcing,” but the concept was the same—work cross-functionally to problem-solve a chunk of the cost away, please. It's now the bread-and-butter of the auto OEMs and their direct suppliers.

This model is still widely held up as Procurement best practice today. But, outside of Big Auto, the large pharma companies, and select multi-national manufacturing companies, few have reached a truly “world class” level of sophistication in Procurement—neither in direct spend nor in the “indirects” arena. We all know what best practice looks like, because companies like GM and Ford have been doing it for half a century. At Ford Motor Company, the CPO sits on the board. Procurement is seen as career-enhancing, and the Procurement function has strong people who are able to execute cross-functionally. The savings even seem to be traceable to the P&L! And yet, it seems, most of us aren't able to replicate this success. Why is that?

One reason is simply that Ford and GM have no choice; they have to be good at Procurement. The Big Auto OEMs buy and assemble a huge volume of parts from around the globe, and they've been operating in an environment with very tight margins (with long periods of losses) for decades. That's why they're truly committed to Procurement from the top down, there is very strong Procurement leadership, there are high-caliber resources who rotate in and out of the function, the function is career-enhancing, working cross-functionally is in its DNA, and execution is of a high quality. All driven by economic necessity, which in many sectors, particularly growth-based and technology sectors, doesn't exist to the same degree.

A second reason why so many companies have failed to reach best practice is that they genuinely tried but failed to do it properly or fully. Some didn't get the right level of sponsorship or investment into the function that was required. Others yet, and there are many, have declared victory when they haven't earned it, which then blocks further progression in those companies.

Bad Best Practice

There is often a perception, particularly among $1 billion plus revenue companies, that their Procurement is “already best in class,” Strategic Sourcing has been done, and “we have it all under control.” There is a tendency for Procurement to say, “We've done a lot already, there's not much left here, we're close to best practice.” Personally, I've probably had more than 100 Procurement leaders tell me this directly, and it's a problem, because they get away with it! The C-Suite views Procurement as a technical discipline and has “full trust that our CPO is taking care of it.” In reality, that's just what the CPO communicates upwards, and it's taken as gospel because he/she is a Procurement professional, and presumably they know what they're doing.

My personal belief is that this phenomenon—call it defensiveness or what you may—blocks many billions of dollars of value being delivered through Procurement globally. I call it “bad best practice,” and it's surprisingly common. It's when Procurement functions falsely believe that they've “already adopted best practice.” The most common area where this plays out is in Strategic Sourcing. I have personally met scores of Procurement leaders who have been given the “Seven-Step Sourcing Methodology” by one of the big consulting firms. These approaches make a lot of sense (and they're all pretty much identical, by the way), but they have to be applied properly. Handing out cookbooks does not make good cooks.

There are other, often very large organizations, including by the 1990s some of the larger auto OEMs, in which the sourcing process has become just a process—very institutionalized, but reduced to a box-ticking exercise. I've seen examples of the work of sourcing teams in organizations that religiously but mindlessly apply a rigorous sourcing process. They have a baseline, they have a supply market study, they've created a stakeholder map, and they have a sourcing strategy. But the baseline is incomplete and it's unclear what the total spend is, the supply market study is interesting but in no way informs the sourcing strategy, the stakeholder map has sat in a file for three months never to be re-looked at, and the sourcing strategy is to bundle the volume and beat up the suppliers.

Bad best practice is a terrible thing, because it blocks real best practice from being put in place. And it's a remarkably common phenomenon. Many times, companies truly believe they have done all the right things. In other instances, CPOs dress up their achievements as a defense mechanism against external consultants or other perceived threats. In all cases it acts as a value blockage.

So, where do we go from here? We've stated that there may be a large opportunity, we've explained how this opportunity has come about, and we've shown that there is a commonly accepted definition of Procurement best practice, but few have managed to attain this gold standard.

The rest of this book looks forward to answering the questions, “How do we get from here to there?,” “How do we maximize the profit potential of Procurement?,” and “What are the fundamental building blocks we need to have in place in order to succeed?”

Why Now?

But you may ask, what's new in all this? Procurement? That's been around for decades. Why this book, and why now?

The answer to this question is that, while this book was written during the global COVID-19 pandemic, its content and messages go well beyond this and are just the accumulated “wisdom” of three Procurement professionals. On the other hand, COVID-19 has clearly put a spotlight on Procurement. As we watched supply chains grind to a halt across the globe, it was easy to spot those who were prepared, those who had their supply chains in order…and the many others who were not prepared, and who were blind-sided by the crisis.

From a Procurement perspective, COVID-19 puts into partial question some of the core supply chain concepts companies have worked hard to implement over the last four decades: JIT (just-in-time) delivery, single sourcing, “best cost country sourcing” from geographically far-flung locations…these concepts drive cost out of the supply chain, but at the expense of increasing exposure to risk. A global disruption like COVID-19 is likely to then test those tightly strung supply chains to the limit.

What the pandemic showed again is that Procurement sits at the heart of the company, it's the interface between the company and its suppliers and service providers—and as companies outsource more and more, the number and scale of service providers grows. Now, the COVID-19 pandemic has made us ask questions like “Do we have enough control over all our key supplier relationships and contracts?,” “Do we have contingency suppliers who can rapidly ramp up capacity for us?” and “Do we have a strong Logistics partner?”

It's commonly accepted now that there will be more global pandemics to come, so let's be sure to learn our lessons from the current one. But also, why not use the post-COVID-19 era to revisit our Procurement cost base? Now is a time for everyone to look at their costs, so why not combine it with a review of our supply chain resilience in the face of a global crisis.

So now does seem like a good time to revisit Procurement, and maybe ask “How far have we really come?” How big is the opportunity, where does it lie, and how do we capture it? These are the questions this book seeks to answer.

But while the pandemic partly provided the impetus for writing this book, at the end of the day, none of the messages in this book are “COVID-specific.” The pandemic has shone a light on Procurement, but what it has revealed was already there. This is not a “COVID-era book,” and we will not be discussing the pandemic further.

About This Book

This book is not an academic book. It represents the distilled opinions of three Procurement consultants who between them have many decades of direct and highly relevant experience. But the views and ideas expressed in this book are not facts. Indeed, you may work for a world-class company to whom many of the statements don't apply. This book is about typical situations, based on what we've found throughout our combined careers, and it's squarely aimed at the “bottom 80%,” rather than the top 20%.

The central thesis of this book is that Procurement is a major underexploited profit lever and in order to maximize its potential, a number of components must be in place, including a fit-for-purpose Procurement function that executes cross-functionally and delivers credible benefits to the business. From there, the book explores each of these components and how to make them work in practice.

The book is aimed at the entire C-Suite and is relevant not only to the CPO, but to the CFO, CEO, COO, and CIO. Why? Because (i) they all stand to gain significantly, and (ii) the CPO needs the rest of the C-Suite if he/she is to succeed. The book is also aimed at the Private Equity Operating Partner (or any other professional) looking to leverage Procurement for EBITDA improvements. We have therefore written the book in an executive style—not from a Procurement perspective, but from a cross-functional perspective. We hope that the book speaks to the entire C-Suite and helps to further educate CEOs and CFOs, in particular, about the opportunity inherent in Procurement.

This book is not an all-encompassing guide to all matters “Procurement.” Look at it as a collection of essays on key topics. All of these topics are of relevance to the CPO. The CFO and other executives might prefer to dip in and out of specific chapters, but we would argue that the Introduction and Conclusion, and the chapters on People, Sourcing Execution, Operating Model, Savings Realization, and Cross-Functional Change are highly relevant to all.

We have tried to pepper the book with relevant and interesting client anecdotes, without boring you with too much detail. Finally, the three authors are management consultants. We think this gives us a very good perspective, since we've seen all the issues discussed here with multiple clients many times over. It also means that we have a large toolbox of consulting frameworks. What we've found is that a small number of these frameworks have proven particularly powerful in transforming Procurement. So, at certain points in the book we intend to share with the reader the “secrets” of some of the more successful Procurement consulting frameworks, and how to get use from them in practice.

We're keen in this book to move beyond the hype, so our intent has been very much to be honest about the Procurement opportunity and how to capture it, and to keep the advice pragmatic and useful. Our aim was to “tell it like it is, warts and all,” the “No b-s!,” C-level guide to Procurement. We hope we've fulfilled that aim. We'd love to hear from you, but please don't write to tell us the following:

- “You're such a bunch of consultants”—We know that, we can't help it! We don't think we know all the answers, but we think we have a valid external perspective; we have humbly showcased only a small number of consulting frameworks that have proved effective over the years.

- “You're repetitive”—Yes, and that's a good thing! There are certain themes that run through the entire book, revisited in Chapter 14: Conclusion, that are touched on in multiple chapters…and these are the things we'd like you to remember; hence the repetition.

- “The book isn't exhaustive”—No, it isn't. This is not a structured textbook. View it more as a collection of essays on some of the most important topics to take into account when transforming Procurement.

- “My company is very good at Procurement. We've already done much of what you're advocating”—Great. We recognize that many companies have sophisticated Procurement functions; this book is aimed at those that don't and are looking to maximize Procurement's potential, as well as those who do but want to get some insight into what other companies are doing that they might learn from.

- “You're down on Procurement”—No, we're not. We're down on bad Procurement, and Procurement whose potential is not maximized, and sometimes we're quite vocal about that. But we are champions of Procurement teams that have devoted their careers to the cause.

- “All your examples feature simple indirect spend categories”—This is true. We tried to feature more complex direct materials case studies, but they're not universally understood and require more explanation, which makes it awkward to refer to them. Hence, we've relied more on indirect category examples, such as Travel, MRO, and Office Supplies. While not “strategic,” these categories are in fact quite complex and served us well in illustrating our points.

- “You're too focused on savings”—The premise of this book is that Procurement is a significant and underexploited profit lever, which does put savings center-stage. Of course, Procurement has other objectives, as discussed in Chapter 8: Non-savings Priorities. But we firmly believe that it's the bottom-line contribution to profitability that puts Procurement on the map, and that is the central thesis of this book.

Of course, you can write to us anyway, but hopefully the above helps to clarify where we're coming from, and what this book is and isn't trying to be.

********************

In the following pages, this book will examine the Procurement Transformation journey from all angles and asks the questions that the C-level executive should be asking:

- Where is the opportunity, and how big is it?

- How do I capture this opportunity and its cost savings in practice?

- Why do so many companies get it wrong, and how do I get it right?

- How do I build the right team in Procurement, and how do I work effectively cross-functionally?

- How do I ensure the savings actually flow to the bottom line?

- What Procurement technologies do we and don't we need?

- How do we use Procurement to minimize supply chain risk and drive non-savings agendas like Sustainability?

- What can we learn from Private Equity and its approach to Procurement?

The central theme that runs right through this book is cross-functionality. Procurement's potential cannot be maximized while operating within a functional silo. That means that the entire C-Suite needs to engage with Procurement, and vice versa. Which is why this is not a book for just the CPO…Procurement is an inherently cross-functional endeavor, and success is only possible if the C-Suite works together.

We hope you enjoy the rest of the book.