Chapter 44

INITIAL PUBLIC OFFERINGS (IPOS)

Welcome to the wonderful world of listed companies!

Theoretically, the principles of financial management that we have developed throughout this book find their full expression in the share price of the company. They apply to unlisted companies as well, but for a listed company, market approval or disapproval – expressed through the share price – is immediate. Being listed enables companies to access capital markets and have a direct understanding of the market value of their companies.

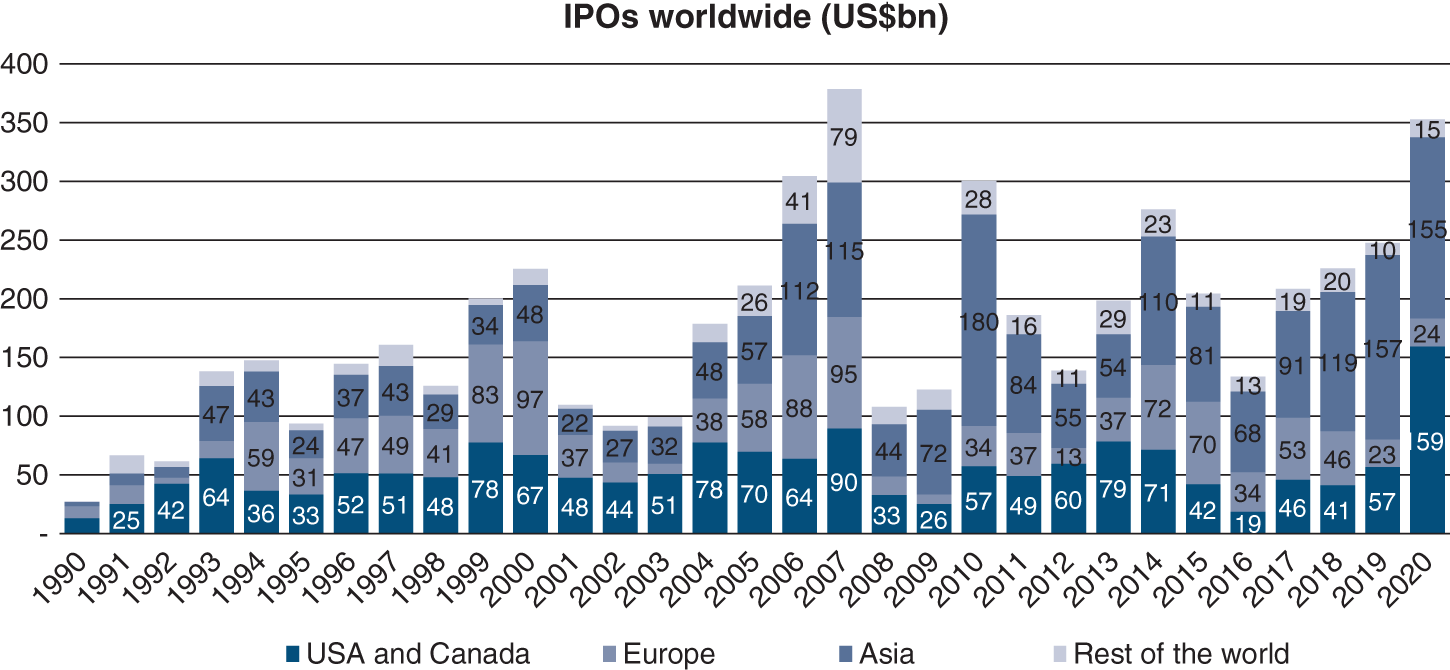

Source: Thomson One Banker, Factset

Being listed enables a company to raise funds in a few weeks or even a few days because:

- financial analysts periodically publish studies reviewing company fundamentals, reinforcing the market's efficiency;

- listing on an organised market enables financial managers to “sell” the company in the form of securities that are bought and sold solely as a function of profitability and risk. Poor management is punished by poor share price performance or worse – from management's point of view – by a takeover offer which leads to a change in management;

- listed companies must publish up-to-date financial information and file an annual report (or equivalent) with the market authority.

We refer the reader interested in the reasons for an IPO to Section 42.2 where we discuss this topic.

Section 44.1 PREPARATION OF AN IPO

It usually takes at least six months between the time the shareholders decide to list a company and the first trading in its shares.

This six-month period provides an opportunity for management to revisit some financial decisions made in the past that were appropriate for an unlisted, family-owned company or for a wholly owned subsidiary of a group, but which would not be suitable for a listed company with minority shareholders, such as:

- preparing accounts in line with accounting standards required for listed companies which may be different from the ones used by private companies, and introduce reporting procedures that cover the whole of the entity to be listed;

- reviewing the group's legal structure in order to ensure that vital assets (brands, patents, customer portfolios, etc.) are fully owned by the group and that the group's legal form and articles of association are compatible with listing (no simplified joint-stock companies and no pre-emptive rights or special agreements in the articles);

- reviewing the group's operating structure, ensuring that it is an independent group with its own means of functioning and that it does not retain the structure of a division of a group or a family-run business (terminate employment contracts with non-operational family members, take out necessary insurance policies, draw up management agreements, etc.);

- drawing up a shareholders' agreement if needed (see Chapter 41);

- introducing corporate governance appropriate for a listed company (independent directors, control procedures, board of director committees, etc. – see Chapter 43);

- reviewing the company's financial structure in order to ensure that it is similar to that of other listed companies in the same sector. This applies particularly to companies under LBO, which will have to partially deleverage via a share issue, at the latest at the time of listing;

- adopting a well-thought-out dividend policy that is sustainable over the long term and that will not compromise the group's development (see Chapter 36);

- introducing a scheme for providing employees with access to the company's shares through the allocation of free shares and/or stock options, etc. (see Chapter 42);

- defining the company strategy in a form that is simple and easy to communicate, which will become the equity story to be told to the market at the time of listing.

From the start of this phase, the company should seek the assistance of an investment bank, which will act as a link between the company and the market. The company will also have to retain the services of a law firm, an accounting firm and possibly a PR agency.

The overall cost of the IPO is between €0.5m and €1m in fixed costs (lawyers, communications agency, roadshows) plus between 5% and 7% of funds raised as fees for the bank syndicate.

Even with this help, the management team will have a very heavy overload of work during these six months because the operational side will not have to be sacrificed for all that!

Section 44.2 EXECUTION OF THE IPO

1/ CHOOSING A MARKET

With rare exceptions, the natural market for the listing is the company's home country. This is where the company is best known to local investors, who are the most likely to give it the highest value. There are obviously a few exceptions, such as L'Occitane and Prada, which elected for a Hong Kong listing (given that both companies' activity is highly developed in Asia) and Criteo, which chose New York to facilitate its US expansion and where most of its peers were listed. But only a very small number of companies from major European countries are not listed in their home country.

Having said that, some stock exchanges act as magnets for some sectors, such as New York for technology companies or London for mining groups.

The next question is whether there should be a second listing on a foreign market. Listing on a foreign market generally triggers direct and indirect costs without any guarantee of greater liquidity or a higher valuation of the company.

Only groups from emerging countries, when their local market is underdeveloped (Russia, Latin America, etc.), gain a clear advantage from a listing in New York, London, Paris or Hong Kong. The Nigerian e-commerce group Jumia is a good example, with its listing in New York in 2019. The Swiss-based mining and trading group Glencore chose London (and Hong Kong) as most mining groups are listed in London.

2/ SIZING THE IPO

Over and above the choice of a stock market (or several) for listing, a certain number of parameters will have to be fixed, including the size of the IPO and the choice between a primary offer (share issue), a secondary offer (sale of shares by existing shareholders) or a mix of the two.

These decisions will be made based on the following:

- whether existing shareholders want to convert all or part of their stakes into cash;

- whether the company needs funds to finance its growth or to deleverage;

- the need to put a sufficient number of shares on the market so that the share can offer a certain amount of liquidity;

- the need to limit the negative signal of the transaction.

These constraints can sometimes turn out to be contradictory. For example, the sale of all of the existing shares on the market by existing shareholders is rarely considered, as this would send a very negative signal to the market. So, when the IPO includes the sale by one or more major shareholders of some of their shares, they will generally be asked to undertake to hold onto the shares that have not been sold for a given period (6–12 months) so as to avoid any heavy impact on the market if they were to sell large volumes of shares immediately after the IPO. This undertaking, or lock-up clause, acts as a reassurance to the market and tempers the negative signal of the operation.

It may also be a good idea to combine the sale of shares by existing shareholders with a capital increase, even if the company has no immediate need of funds. The message sent by an IPO through a capital increase is, by definition, more positive. The newly listed company will be able to speed up its development and to tap a new source of funding, which is why most IPOs are partly primary, whether to a larger or smaller degree.

THE 10 LARGEST IPOS WORLDWIDE OF ALL TIME

| Rank | Company | Stock exchange | Sector | Proceeds ($bn) | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saudi Aramco | Saudi Arabian stock exchange | Oil | 25.6 | 2019 |

| 2 | Alibaba | New York (NYSE) | Ecommerce | 25 | 2014 |

| 3 | Agricultural Bank of China (ABC) | Shanghai and Hong Kong | Bank | 22 | 2010 |

| 4 | Softbank | Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) | Conglomerate | 21.3 | 2018 |

| 5 | Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) | Shanghai and Hong Kong | Bank | 19.1 | 2006 |

| 6 | NTT DoCoMo | Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) | Telecom and Internet | 18.1 | 1998 |

| 7 | Visa | New York (NYSE) | Financials | 17.9 | 2008 |

| 8 | AIA | Hong Kong (HKEx) | Insurance | 17.8 | 2010 |

| 9 | Enel | Milan and New York (NYSE) | Utility | 16.5 | 1999 |

| 10 | New York (NASDAQ) | Internet | 16.0 | 2012 |

Source: Dealogic.

3/ IPO TECHNIQUES

While the classic method of listing remains the constitution of an order book (see Chapter 25), two new techniques have developed strongly in recent years: direct listing and merger with a SPAC (Special Purpose Acquisition Company).

Direct listing is a simple IPO method: a company wishing to become listed simply lists its shares on a regulated market and lets supply (from shareholders wishing to monetise their investment) and demand (from investors wishing to buy shares) set the equilibrium price. In the United States, a reference price is indicated but is not binding. This technique does not therefore require the intervention of a bank as is the case for IPOs by setting up an order book.

This technique is normally less costly than an IPO through the creation of an order book because the company saves the banks' fees and, above all, the operation is theoretically carried out without any discount for the selling shareholders.

But direct listing does not only have advantages. First of all, the company cannot raise funds by this method, only existing shares are exchanged. Furthermore, the sale of large blocks of shares is not possible or not optimal. Indeed, investor demand may be relatively limited in the absence of a major marketing exercise carried out by the banks in building up the order book (book building with meetings with investors, distribution of analysts' notes, etc.). Finally, in the absence of a method for price discovery before listing (which is in reality book building), and of mechanisms for limiting price variations (greenshoe, lock up), the volatility of the price during the first few weeks of listing is likely to be significantly higher in the case of a direct listing than in the case of a traditional IPO.

A direct listing is therefore reserved for a certain type of company: one that is already well known to investors (and therefore generally large), with an already large shareholder base (often consisting in part of the company's employees), wishing to provide liquidity to its shareholders, but not needing to raise funds.

Spotify chose this IPO mode in 2018 followed by Slack in 2019 and Asana and Palentir in 2020. In Europe this technique has been used mainly in the case of spin-offs (e.g. ArcelorMittal/Aperam, HiPay/HiMedia).

SPACs or “blank cheques companies” are shells that get listed with the intention of acquiring and merging within 18–24 months with a private operating company (which will then become a listed company). The shareholders of SPACs have the right to vote for or against the acquisition (known as despacking). This is obviously crucial as it allows the SPAC to fulfil its mission. If the management of a SPAC fails to find a suitable target within 18–24 months, the vehicle is dissolved and the funds returned to the shareholders. At the time of despacking, shareholders may also choose to have their initial investment returned to them. Paradoxically, this latter option actually encourages them to vote for the deal regardless of their views on the transaction. If they think the deal is going well, they vote for it and stay; if not, they vote yes and exit and ask for their shares to be returned. But by asking for the exit, they can jeopardise the operation because if the SPAC does not have enough funds to complete the acquisition, it is cancelled.

It is quite rare that the transaction is completed for an amount less than or equal to the amount raised by the SPAC initially (a few hundred million euros). If the target is larger, either the target's shareholders remain shareholders (majority or not) in the listed company, or the SPAC raises funds again from institutional investors at the time of the acquisition (this is known as PIPE, Private Investment in Public Equity). This is a second validation by the market of the rationale and price of the acquisition.

The management of SPAC receives almost 20% of the shares for free when SPAC is created and listed. The management invests limited funds (a few million dollars or euros) but they are really at risk, because if SPAC does not despack, the funds are lost (these funds pay for the operating costs of SPAC and the costs of its listing).

When the initial shareholders of the SPAC target are paid in SPAC shares, the operation has the same result as a classical IPO with some differences:

- For the exiting shareholders, selling to a SPAC means saving the IPO discount since the company is sold privately.

- For the remaining shareholders, if the company has to raise funds during the operation, the IPO discount must be set against the dilution linked to the free shares of the SPAC's management and the warrants (issued at the time of the IPO and allowing to subscribe to new shares at a higher price, generally $11.5 for shares issued at $10).

- For institutional investors, they do not benefit from the IPO discount but they guarantee themselves a place in the operation, which an allocation in a classic IPO would not have allowed.

- The real losers are the investment banks who receive a much lower fee than in a traditional IPO.

These new methods still suffer from an image problem: direct listing exists in Europe, but mainly for small companies; SPACs are often regarded as the operations of financial pirates. But their institutionalisation in the US, with 219 SPACs raising $79bn (compared with $67bn for traditional IPOs in 2020), may change this image. Although their acceleration at the beginning of 2021 (340 SPACs raising $106.6bn) may give rise to fears of a speculative boom that will deflate, without them falling back into the margins. A few SPACs have gone public in Europe.

Atypically, some small unlisted companies are being absorbed by a listed structure, without operational activities or having previously sold them (a “shell”), in order to access the listing more quickly and at lower cost (AAA in 2021). But in most cases, a free float has to be recreated.

Section 44.4 UNDERPRICING OF IPOS

If statistics are to be believed, the share price of a newly floated company generally – but there are a number of exceptions – sees a small rise over the IPO price in the days following flotation (see Section 25.2). It would also appear that this discount at which shares are sold or issued at the time of an IPO is volatile over time, compared with an equilibrium value – high in the 1960s, lower in the 1970s to 1980s, and then high again in the 2000s before dropping in recent years. Following research, many different explanations for this discount have been put forward. The main ones are:

- This underpricing is theoretically due to the asymmetry of information between the seller and the investors or intermediaries. The former has more information on the company's prospects, while the latter have a good idea of market demand. A deal is therefore possible, but price is paramount.

- Signal theory says that the sale of shares by the shareholders is a negative signal, so the seller has to “leave some money on the table” in return for ensuring that the IPO goes off smoothly and to investors' satisfaction.

- Asymmetrical information amongst the different investors. “Informed” investors will only be interested in good deals and will not be tempted by overvalued IPOs. Less well-informed investors, who will thus be involved in all financings, will find that they are better served in unattractive operations. They will not be as present on more attractive deals. In seeking to retain all the investors who provide valuable and necessary liquidity to the market, IPOs are carried out at a discount.

- There are some who argue (not very convincingly) that underpricing can limit the risk of legal disputes with investors who would feel as if they had been swindled because they'd made a bad investment.

Section 44.5 HOW TO CARRY OUT A SUCCESSFUL IPO

The fact that a number of IPOs are cancelled or postponed (2018–2020 has seen, amongst others, tech start-ups WeWork and Airbnb in the USA, petrochemical company Sibur in Russia) shows that this is a tricky process and that success is not always guaranteed.

A successful IPO is the combination of a number of factors:

- the intrinsic quality of the company: market share, growth and clarity of the activity, management experience, capital structure, should not be unusual, etc. These factors are assessed on the basis of comparable companies that are already listed, since the listing of the company is offering a new choice to investors within the same investment universe;

- a clear and convincing explanation of the sellers' motivations, as the market will always fear that they are selling their shares because their best results have already been achieved. This is why a flotation through a share issue for financing investments is preferable to the sale of shares (signalling theory);

- agreement on the price, which is much easier to achieve when the stock markets are performing well, and very difficult to achieve when they are performing badly. This is the most frequent reason for cancelling an IPO.

From a tactical point of view, and when the stock markets are performing badly, marketing is crucial. Readers, who have been aware since Chapter 1 that a good financial director is first and foremost a good marketing manager, will not be surprised! Marketing involves:

- familiarising investors with the stock market candidate a few months before the roadshows themselves begin, through informal meetings (pilot fishing);

- entry into the company's capital by investors seen as cornerstone investors a few weeks before the IPO when the regulations allow this, or during the IPO but with a guaranteed allocation, which will encourage other investors to follow suit. This is particularly prevalent in Asia. Thus, Thailand's largest retailer, Central Retail Corp, welcomed Singapore sovereign wealth fund GIC and funds run by Capital Research Management as international cornerstone investors backing its IPO in January 2020; an anchor investor is an institutional investor placing a large order in the order book, thereby acting as a valuation driving force. The Monetary Authority of Singapore acted as an anchor investor in the March 2020 IPO of SBI Cards.

- tight management of communication over the envisaged price. For example, Glencore let it be known that it was considering a flotation of over $60bn and when a lower price was announced, this was perceived as good news. This is called behavioural finance! It is true that the difficulty of valuing this complex group made this manoeuvre much easier;

- a price seen as lower than the equilibrium value, enabling investors to hope for capital gains after a few months. For example, Shurgard fixed its IPO price at the bottom of the indicative bracket. Seven days after listing, the share price stabilised at 13% above the IPO price.

Sometimes the market is a buyers' market, and these buyers do not hesitate to twist the arm of investors seeking liquidity. It is just as well to be aware of this and not try to play another game if you want to list a company on the stock exchange.

The first days of listing are crucial, because starting a stock market career with a share price that is lower than the IPO price (Uber in May 2019) does not make a very good impression on investors. On the other hand, slightly undervaluing the share when it is listed means that the price will rise by a few percentage points during its first days of listing. This puts everybody in a good mood!

Finally, in the long term the company and its managers will have to learn to live with daily constraints on their behaviour imposed by the periodical distribution of financial information, by managing earnings so as not to disappoint investors and thereby risk lower levels of investment than an unlisted company might face, and because they will be taking fewer risks in general. Furthermore, all shareholders must be treated equally, and managers are going to have to get used to the value of the company being published every day; sometimes this value will be low even though results are good. This can have an impact on the morale of employees and on shareholders' assets, and it could lead to a change of control in the event of major changes in the capital structure.

That's just life on the stock exchange!

Section 44.6 PUBLIC TO PRIVATE

A company (or the shareholders) will first start considering a public-to-private move when the reasons why it decided to list its shares in the first place, for the most part, become irrelevant. It has to weigh the cost of listing – direct costs: stock exchange fees, publication of annual reports, meetings with analysts, employment of investor relations staff; and indirect costs: requirement to disclose more information to the public and to competitors, market influence on strategy, management's time spent talking to the market, etc. – against the benefits of listing when deciding whether the company should remain listed or not. This is especially the case if:

- the company no longer needs large amounts of outside equity and can self-finance future financing requirements. The company no longer has any ambition to raise capital on the market or to pay for acquisitions in shares;

- the stock exchange no longer provides minority shareholders with sufficient liquidity (which is often rapidly the case for smaller companies which only really benefit from liquidity at the time of their IPO). Listing then becomes a theoretical issue and institutional investors lose interest in the share;

- the annual cost of the listing (starting at €200k for a small company and running into millions for larger ones) has become too expensive in comparison with the benefits;

- the company no longer needs the stock exchange in order to increase awareness of its products or services.

The second type of reason why companies delist is financial. Large shareholders, whether majority shareholders or not, may consider that the share price does not reflect the intrinsic value of the company. Turning a problem into an opportunity, such shareholders could offer minority shareholders an exit, thus giving them a larger share of the creation of future value.

The operation can be complex. Indeed, beyond the technical constraints, it will depend on the ability of the majority shareholder to convince the minority shareholders to sell their shares. Alternatively, for companies with dispersed capital, it will be necessary to find a new investor ready to make an offer, usually with recourse to debt. Delisting is possible if the majority shareholder exceeds a threshold, often 90% or 95%, as it is then obliged to acquire the rest of the shares. This is known as a squeeze-out. In practice, this amounts to forcing minority shareholders to sell any outstanding shares. Because this is a form of property expropriation, the price of the operation is analysed very closely by the market regulator. In most countries, a fairness opinion has to be drawn up by an independent, qualified financial expert.

If investors are below the squeeze-out threshold, they first have to launch an offer on the company's shares, hoping to go above the squeeze-out threshold so as to be able to take the company private. This is a P-to-P, public-to-private, deal.

Following a change of control, the new majority shareholder who wishes to hold 100% of the capital of its new subsidiary in order to more easily implement the expected synergies will then have to proceed with a delisting through a squeeze-out.