Chapter 47

LEVERAGED BUYOUTS (LBOs)

Leverage on management!

A leveraged buyout (LBO) is the acquisition of a company by one or several private equity funds who finance their purchase with a significant amount of borrowed funds. Most of the time, LBOs bring improvements in operating performance as the management is highly motivated (high potential for capital gains) and under pressure to rapidly pay down the debt incurred.

Why are financial investors willing to pay more for a company than a trade buyer that can extract synergies? Are they miracle workers? Watch out for smoke and mirrors. Value is not always created where you think it will be. Agency theory will be very useful, as the main innovation of LBOs is new corporate governance, which, in certain cases, is more efficient than that of listed or family companies.

Section 47.1 LBO STRUCTURES

1/ PRINCIPLE

The basic principle is to create a holding company, the sole purpose of which is to hold shares. The holding company borrows money to buy another company, often called the “target”. The holding company will pay interest on its debt and pay back the principal from the cash flows generated by the target. In LBO jargon, the holding company is often called NewCo or HoldCo.

Operating assets are the same after the transaction as they were before it. Only the financial structure of the group changes. Equity capital is sharply reduced and the previous shareholders sell part or all of their holding.

From a strictly accounting point of view, this setup makes it possible to benefit from the effect of financial gearing (see Chapter 13).

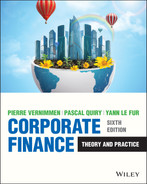

Now let us take a look at the example of the organic product group Wessanen1 (brands Bjorg, Clipper, Altereco, etc.), acquired in September 2019 by the LBO fund PAI and the investor Charles Jobson for an enterprise value of €929m. Wessanen generated 2018 sales of €628m and an EBITDA of €58m. The acquiring holding company was set up with €484m of equity and €445m of debt.

Best Food of Nature debt is made up of a 7-year loan for €390m, and a second-lien debt maturing in 2027 (i.e. one year later) for €55m.

The balance sheets are as follows:

| Revalued balance sheet of Wessanen | Best Food of Nature's unconsolidated balance sheet | Group's consolidated balance sheet | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operating assets €929m | Shareholders' equity €929m | Shares of Wessanen €929m | Shareholders' equity €484m | Operating assets €929m | Shareholders' equity €484m |

| Debt €445m | Debt €445m | ||||

Note that consolidated shareholders' equity, on a revalued basis, is now 55% lower than it was prior to the LBO.

The profit and loss statement, meanwhile, is as follows:

| (€m) | Wessanen | Best Food of Nature | Consolidated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Earnings before interest and tax | 58 | 442 | 58 |

| − Interest expense at 5% | 0 | 22 | 22 |

| − Income tax at 25% | 14 | 0 | 93 |

| = Net income | 44 | 22 | 27 |

Best Food of Nature does not pay corporate income tax as dividends paid by Wessanen are tax-free coming from income already taxed at the Wessanen level.

2/ TYPES OF LBO TRANSACTIONS

Leveraged buyout (LBO) is the term for a variety of transactions in which an external financial investor uses leverage to purchase a company. Depending on how management is included in the takeover arrangements, LBOs fall into the following categories:

- a (leveraged) management buyout or (L)MBO is a transaction undertaken by the existing management together with some or all of the company's employees;

- if new management is put in place, it will be called a management buy-in or MBI;

- when outside managers are brought in to reinforce the existing management, the transaction is called a BIMBO, i.e. a combination of a buy-in and a management buy-out. This is the most common type of LBO in the UK;

- an owner buyout (OBO) is a transaction undertaken by the largest shareholder to gain full control over the company.

3/ TAX ISSUES

Obtaining tax consolidation between the holding company and the target is one of the drivers of the overall structure, as it allows financial costs paid by the holding company to be offset against pre-tax profits of the target company, reducing the overall corporate income tax paid.

In some countries, it is possible to merge the holding company and the target company soon after the completion of the LBO. In other countries this is not the case, as the local tax administration argues it is contrary to the target's interest to bear such a debt load. Provided tax consolidation is possible between the target and Holdco, this has no material consequence. If tax consolidation is not possible because, for example, the Holdco stake in the target company has not reached the required minimum threshold, then a debt push down may be necessary.

In order to perform a debt push down, the target company pays an extraordinary dividend to Holdco or carries out a share buy-back financed by debt, allowing Holdco to transfer part of its debt to the target company where financial expenses can be offset against taxable profits. If the target company is still listed, an independent financial expert is likely to be asked to deliver a solvency opinion testifying that the target debt load does not prevent it from properly operating in the foreseeable future.

4/ EXIT STRATEGIES

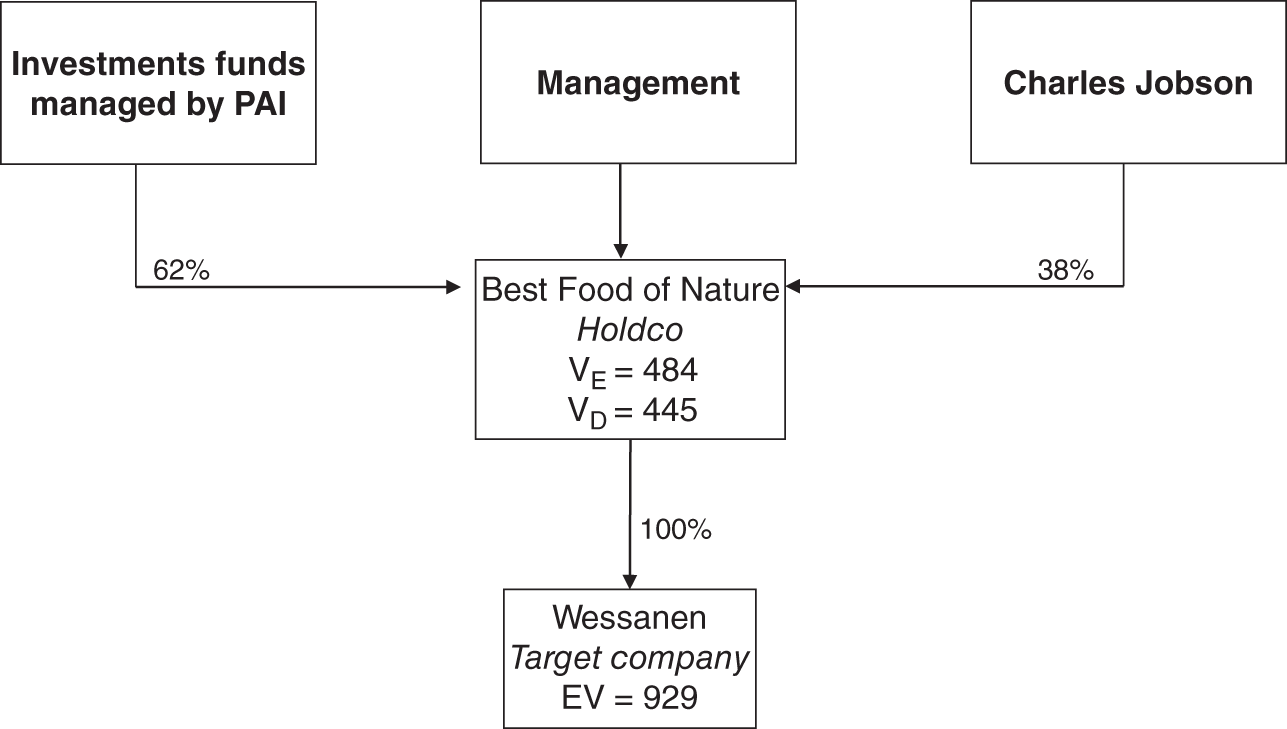

The lifespan of an LBO depends both on the speed at which the LBO fund can improve the company's performance and its capacity to sell it on to a third party or on the stock market. It is rarely less than two years in periods of euphoria and it can be as long as seven or eight years during lean times. There are several exit strategies:

- Sale to a trade buyer. Our general comment here is that in most cases financial investors bought the company because it had not attracted trade buyers at the right price. When the time has arrived for the exit of the financial buyer, either the market or the company will have had to have changed for a trade buyer to be interested. The private equity firm Apollo exited its investment in Endemol in 2020 through a sale to Banijay.

- Initial public offering. This strategy must be implemented in stages, and it does not allow the sellers to obtain a control premium; most of the time they suffer from an IPO discount. It is more attractive for senior management than a trade sale. In 2019, Verallia was IPOed by Apollo and Bpifrance.

- Sale to another financial investor, who, in turn, sets up another LBO. These “secondary” LBOs are becoming more and more common and we also see tertiary or even quaternary LBOs such as B&B. Hence, in 2021, EQT bought back the laboratory group Cerba to Partners Group and PSP.

- A leveraged recapitalisation (or dividend recap). After a few years of debt reduction thanks to cash flow generation, the target takes on additional debt with the purpose of either paying a large dividend or repurchasing shares, thereby improving the performance of the fund and its IRR. The result is a far more financially leveraged company. These had disappeared after 2008 following debt markets' disfavour for LBOs, but have reappeared again since 2013, an example being Apria in 2021.

Source: Data from Invest Europe

- A debt to equity swap allowing debtholders to gain control of the company when its debt load becomes too heavy to be repaid by the company's cash flows which, most of the time, have slumped compared to projections. Existing shareholders have refused to put in more equity to pay back part of the debt but they have agreed to allow a share issue to take place and to be diluted.

- A bankruptcy when cash flows generated by the operating company are insufficient to allow for enough dividends to be paid to Holdco and when debtholders and shareholders cannot reach an agreement on a capital restructuring (new equity, lower interest rates, longer repayment schedule, etc.).

If the company has grown or become more profitable on the financial investors' watch, it will be easier for them to exit. Improvement may take the form of an internal growth strategy by geographical or product extension, a successful redundancy or cost-cutting plan or a series of bolt-on acquisitions in the sector. Size is important if flotation is the goal, because small companies are often undervalued on the stock market, if they manage to get listed at all.

That being said, a company whose LBO has failed as a result of an inability to pay off its debt is often in a pitiful state. The investment tap has been turned off, the most talented staff have seen the writing on the wall and have left and the remaining staff lack motivation. Turning such a company around presents a serious challenge!

Section 47.2 THE PLAYERS

The LBO market has become highly structured since the early 1990s. All the direct players (funds, banks, investors) and indirect players (financial, legal, strategic and management advisors) treat the LBO business as a specific business with dedicated teams. Industrialists and managers have become familiar with this type of structure.

1/ POTENTIAL TARGETS

The transactions we have just examined are feasible only with certain types of target companies. The target company must generate profits and cash flows that are sufficiently large and stable over time to meet the holding company's interest and debt payments. The target must not have burdensome investment needs. Mature companies that are relatively shielded from variations in the business cycle make the best candidates: food, retail, water, building materials, real estate, cinema theatres and business listings providers are all prime candidates.

THE WORLD'S 10 LARGEST LBOs

| Target | Date | Sector | Equity sponsor | Value ($bn) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TXU | 2007 | Energy | KKR/TPG | 45 |

| Equity Office | 2006 | Real Estate | Blackstone | 36 |

| HCA | 2006 | Health | Bain/KKR | 33 |

| RJR Nabisco | 1988 | Food | KKR | 30 |

| Heinz | 2013 | Food | Berkshire Hathaway/3G Capital | 28 |

| Kinder Morgan | 2006 | Energy | Carlyle | 27 |

| Harrah's Entertainment | 2006 | Casino | Apollo/TPG | 27 |

| First Data | 2007 | Technology | KKR | 27 |

| Clear Channel | 2006 | Media | Bain/Thomas Lee | 27 |

| Alltel | 2007 | Telecom | TPG/Goldman Sachs | 27 |

Source: Data from Thomson Financial

The group's LBO financing already packs a hefty financial risk, so the industrial risks had better be limited. Targets are usually drawn from sectors with high barriers to entry and minimal substitution risk. Targets are often positioned on niche markets and control a significant portion of them.

Traditionally, LBO targets were “cash cows”. As the euphoria subsided however, a shift has been observed towards companies exhibiting higher growth or operating in sectors with opportunities for consolidation (build-up). As the risk aversion of investors decreases, some private equity funds have carried out LBOs in more difficult sectors.

Targets must now also show a satisfactory environmental, social and governance (ESG) policy, as these items are now fully included in the investment criteria of the funds and their investors.

2/ THE SELLERS

Recently, more than half of all targets have been companies already under an LBO, sold by one private equity investor to another, for the second, third or more times, such as Cerba, Armacell, etc.

There are many European SMEs that were set up or grew substantially in the 1960s and 1970s, run by a majority shareholder-manager. These shareholder-managers are now reaching retirement age and may be tempted by LBO funds for the disposal of their companies, rather than selling them to a direct competitor (often seen as the devil incarnate) or seeking a stock market exit, which may be difficult. All the more so when the company bears the family name, which may disappear if it is sold to another industrial player.

Some sectors are so concentrated that only LBO funds can buy a target as the antitrust authorities would never allow a competitor to buy it or would impose severe disposals, making such an acquisition unpalatable to many trade buyers. The larger transactions fall into the latter category (Venelia, AkzoNobel's chemicals division).

Finally, some listed companies that are undervalued (often because of liquidity issues or because of lack of attention from the investment community because of their size) sometimes opt for public-to-private (P-to-P) LBOs. In the process, the company is delisted from the stock exchange. Despite the fact that these transactions are complex to structure and generate high execution risk, they are becoming more and more common thanks to the drop in market values (Wessanen).

3/ LBO FUNDS ARE THE EQUITY INVESTORS

Setting up an LBO requires specific expertise, and certain investment funds specialise in them. These are called private equity sponsors, because they invest in the equity capital of unlisted companies.

LBOs are particularly risky because of their high gearing. Investors will therefore undoubtedly require high returns. Indeed, required returns are often in the region of 15% p.a. In addition, in order to eliminate diversifiable risk, these specialised investment funds often invest in several LBOs.

In Europe alone, there are over 100 LBO funds in operation. The US and UK LBO markets are more mature than those of Continental Europe. The Asian market is nascent. For this reason, Anglo-Saxon funds such as BC Partners, Blackstone, Carlyle, Cinven, CVC, TPG and KKR dominate the market, particularly when it comes to large transactions. In the meantime, the purely European funds, such as Eurazeo, Industri Kapital and PAI, are holding their own, generally specialising in certain sectors or geographic areas.

To reduce their risk or increase their target size, LBO funds also invest alongside another LBO fund or their own investors (they form a consortium) or an industrial company (sometimes the seller) with a minority stake. In this case, the industrial company contributes its knowledge of the business and the LBO fund its expertise in financial engineering, the legal framework and taxation.

Most of the private equity sponsors contribute equity for between 30% and 50% of the total financing. The time (first half of 2007) when they accounted for 20% of financing is over! In order to facilitate the transfer of cash, part of the equity could also take the form of highly subordinated convertible bonds, which will be converted in the event of the company experiencing financial difficulties. Interest on such bonds is tax-deductible.

Materially, LBO funds are organised in the form of a management company (the general partner or GP) that is held by partners who manage funds raised from institutional investors4 or high-net-worth individuals (the limited partners, or LPs). When funds need to be raised quickly, a bank may advance the funds pending the raising of equity (an equity bridge). LBO funds then call on the limited partners for the funds that they have committed to bringing, as investments are made. LPs also sometimes invest directly alongside the fund, which strengthens its intervention capacity. This is known as co-investment.

When a fund has invested more than 75% of the equity it has raised, another fund is launched. Each fund is required to return to investors all of the proceeds of divestments as these are made, and the ultimate aim is for the fund to be liquidated after a given number of years, and at the latest 10 years.

The management company, in other words the partners of the LBO funds, is paid on the basis of a percentage of the funds invested (c. 2% of invested funds) and a percentage of the capital gains made (often close to 20% of the capital gain) above a minimum rate of return of 6% to 8% (the hurdle rate), known as carried interest.

Some funds decide to list their shares on the stock market, like Blackstone did in 2007,5 while others such as 3i and Wendel are listed for historical reasons.

4/ THE LENDERS

For smaller transactions (less than €10m), there is a single bank lender, often the target company's main bank or a small group of its usual bankers (club deal).

For larger transactions, debt financing is more complex. The LBO fund negotiates the debt structure and conditions with a pool of bankers. Most of the time, bankers propose a financing to all candidates (even the one advising the seller). This is staple financing.

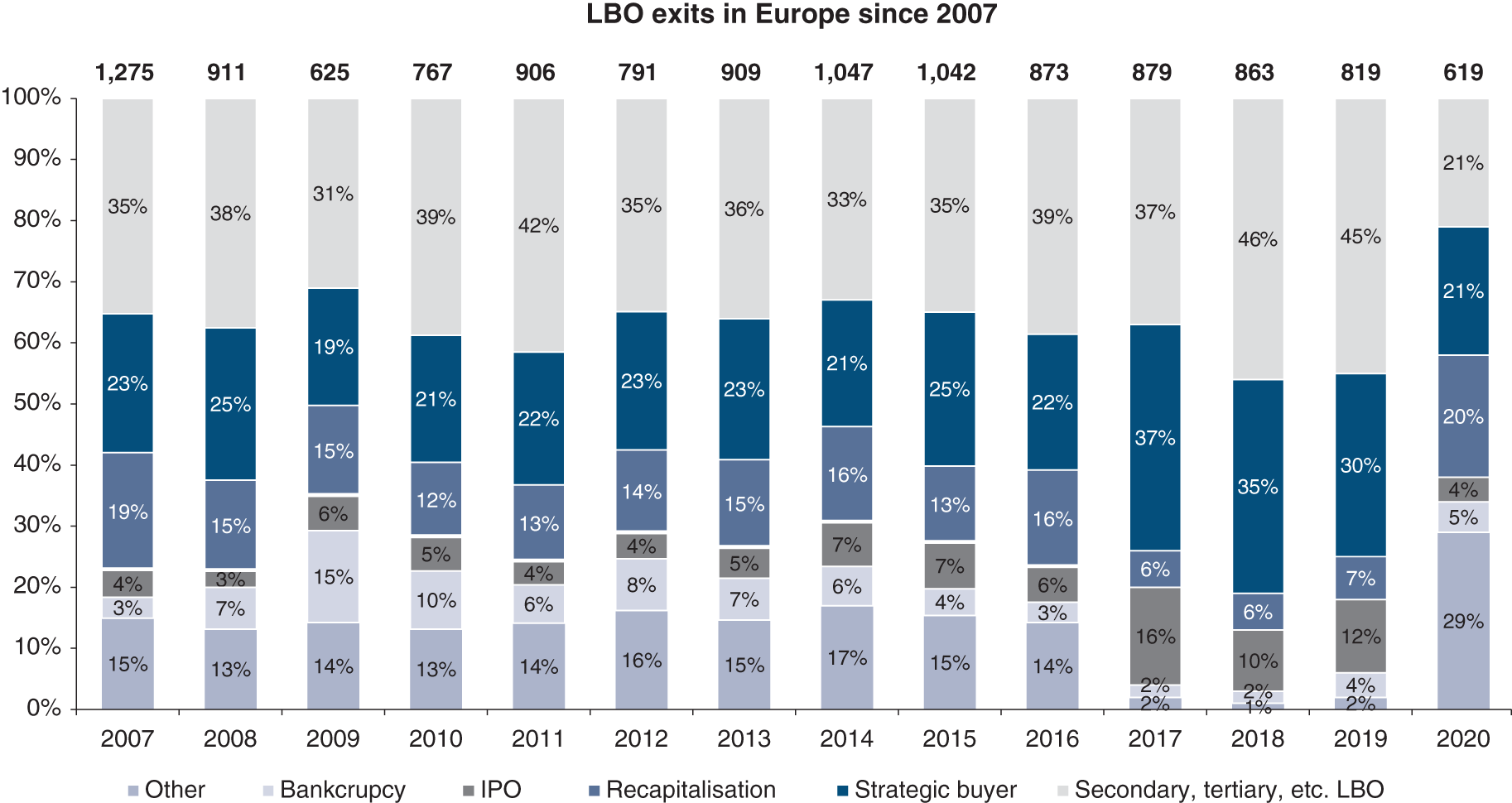

The high degree of financial gearing requires not only traditional bank financing, but also subordinated lending and mezzanine debt, which lie between traditional financing and shareholders' equity. This results in a four-tier structure: traditional, secured loans called senior debt, to be repaid first; subordinated or junior debt, to be repaid after the senior debt; mezzanine financing, the repayment of which is subordinated to the repayment of the junior and senior debt; and, last in line, shareholders' equity.

Sometimes, shareholders of the target grant a vendor loan to the LBO fund (part of the price of which payment is deferred) to help finance the transaction.

(a) Senior debt

Senior debt generally totals three to five times the target's EBITDA.6 It is composed of several tranches, from least to most risky:

- tranche A is repaid in equal instalments over six to seven years;

- tranches B and C are repaid over a longer period (seven to eight years for the B tranche and eight to nine years for the C tranche) after the A tranche has been amortised. Tranche C has a tendency to disappear.

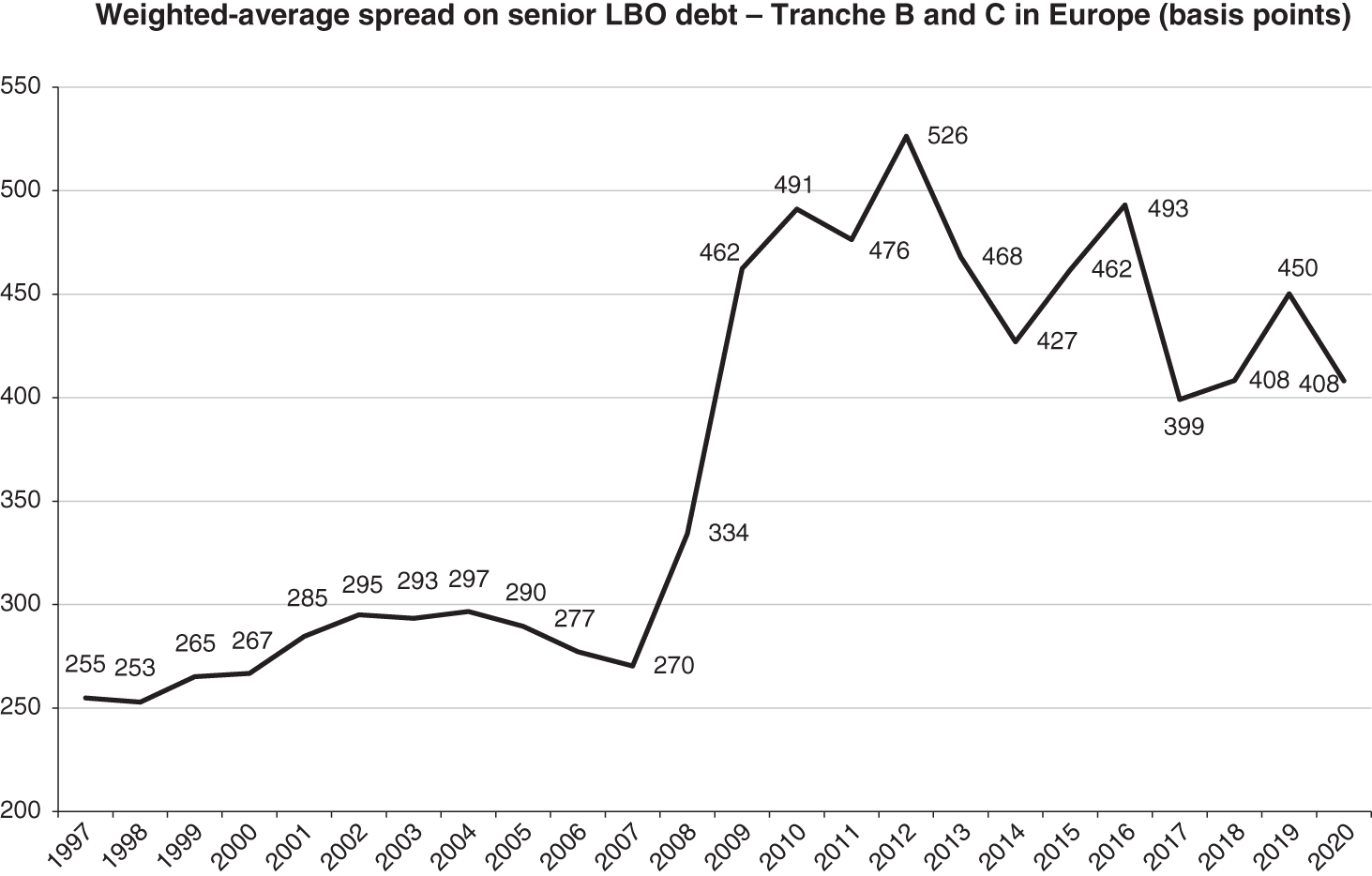

Each tranche has a specific interest rate, depending on its characteristics (tranches B and C will be more expensive than tranche A because they are repaid after and are therefore more risky). This rate is relatively high (several hundred base points above the Euribor; 100 base points = 1%).

For senior debt, guarantees are held on the target's shares, along with covenants. When it is a cov-lite (covenant light) transaction, then they have been reduced or are non-existent!

When the debt amount is high, the loan will be syndicated to several banks (see Section 25.8). The senior debt can take the form of a single tranche B: Term loan B which can then be placed not only with banks but also with institutional investors.

An alternative (or complement) is to issue Senior Secured Notes (Senior High Yield Notes) if the size of the transaction is sufficient, without them being subordinated, such as those we will see in the next paragraph.

Collateralised debt obligation (CDO) funds have been created, which subscribed or bought tranches of LBO debt. Their investors are mainly insurance companies, hedge funds and pension funds.

(b) Junior or subordinated debt

High-yield bond (subordinated notes) issues are sometimes used to finance LBOs, but this technique is reserved for the largest transactions so as to ensure sufficient liquidity. In practice the lower limit is around €150m. An advantage of this type of financing is that it carries a bullet repayment and a maturity of 7–10 years. Given the associated risk, high-yield LBO debt, as the name suggests, offers investors high interest rates, as much as 600 basis points over government bond yields. There has definitely been an upsurge in high-yield bonds used to fund LBOs since late 2009. This is a window of opportunity that shut very suddenly at the start of the Covid-19 crisis but reopened quite quickly in summer 2020.

Mezzanine debt also comes under the heading of (deeply) subordinated debt, but is unlisted and provided by specialised funds. As we saw in Chapter 24, certain instruments accommodate this financing need admirably. These “hybrid” securities include convertible bonds, mandatory convertibles, warrants, bonds with warrants attached, etc.

Given the associated risk, investors in mezzanine debt – “mezzaniners” – demand not only a high return, but also a say in management. Accordingly, they are sometimes represented on the board of directors.

Returns on mezzanine debt take three forms: a relatively low interest rate (5%–6%) paid in cash; a deferred interest or payment in kind (PIK) for 5%–8%; and a share in any capital gain when the LBO fund sells its stake.

Most of the time, mezzanine debt is made of bullet bonds7 with warrants attached. Mezzanine financing is a true mixture of debt and shareholders' equity. Indeed, mezzaniners demand returns more akin to the realm of equity investors, around 10% to 12% p.a.

Subordinated and mezzanine debt offer the following advantages:

- they allow the company to lift gearing beyond the level acceptable for bank lending;

- they are longer term than traditional loans and a portion of the higher interest rate is paid through a potential dilution. The holders of mezzanine debt often benefit from call options or warrants on the shares of the holding company;

- they make upstreaming of cash flow from the target company to the holding company more flexible. Mezzanine debt has its own specific terms for repayment, and often for interest payments as well. Payments to holders of mezzanine debt are subordinated to the payments on senior and junior debt;

- they make possible a financing structure that would be impossible by using only equity capital and senior debt.

LBO financing spreads the risk of the project among several types of instruments, from the least risky (senior debt) to the most risky (common shares). The risk profile of each instrument corresponds to the preferences of a different type of investor.

(c) Securitisation

LBOs are sometimes partly financed by securitisation (see Chapter 21). Securitised assets include receivables and/or inventories when there is a secondary market for them. The securitisation buyout is similar to the standard securitisation of receivables, but aims to securitise the cash flows from the entire operating cycle.

(d) Other financing

For small and medium-sized LBOs, senior and junior debt can be replaced by a unitranche debt. This is a bullet debt subscribed by an investment fund specialised in debt, whose cost is around 5%–8%, i.e. between the cost of a senior debt and that of a junior debt. Contrary to Term loan B, unitranche debt is not liquid.

Financing at the level of the operating company generally tops up the financing of Holdco:

- either through a revolving credit facility (RCF), which can help the company deal with any seasonal fluctuation in its working capital requirements;

- an acquisition facility, which is a line of credit granted by the bank for small future acquisitions;

- or a capex facility to finance capital expenditures.

At the peak of the cycle, where the most complex and inventive structures flourish such as a tranche of bank debt that falls in between senior debt and mezzanine debt – second lien debt, which is first-ranking but long-term debt, and interim facility agreements, which enable the LBO to go ahead even before the legal paperwork (often running to hundreds of pages) has been finalised and fully negotiated. Interim facility agreements are very short-term debts that are refinanced using LBO loans. “First-loss-second loss” bank loans can complement operations financed by a unitranche debt.

(e) The larger context

The prices of the target companies acquired under LBOs changes in tandem with the evolution of stock market multiples, interest rates, and banks' appetite to lend.

Source: Data from Standard & Poor's

Since the 2008 crisis, lenders' assessment of the risk of LBOs has been revised upwards considerably, thereby inducing an increase in their required remuneration. Mid-2020 the LBO market has closed over a short period of time but resumed rapidly with a record second half of the year.

Source: Data from Standard & Poor's

5/ THE EMPLOYEES AND MANAGERS OF A COMPANY UNDER AN LBO

The managers of a company under an LBO may be the historical managers of the company or new managers appointed by the LBO fund. Regardless of their background, they are responsible for implementing a clearly defined business plan that was drawn up with the LBO fund when it took over the target. The business plan makes provision for operational improvements, investment plans and/or disposals, with a focus on cash generation because, as the reader is no doubt aware, cash is what is needed for paying back debts!

LBO funds tend to ask managers to invest large amounts of their own cash in the company (often 1 to 2 years of earnings), and even to take out loans to be able to do so, in order to ensure that management's interests are closely aligned with those of the fund. Investments could be in the form of warrants, convertible bonds or shares, providing managers with a second leverage effect, which, if the business plan bears fruit, will result in a five- to ten-fold or even greater increase in their investment. On the other hand, if the business plan fails, they will lose everything. So, only in the event of success will the management team get a partial share of the capital gains and a higher IRR on its investment than that of the LBO funds. This arrangement is known as the management incentive package.

In some cases, following several successful LBOs, the management team can, as a result of this highly motivating remuneration scheme, take control of the company,8 having seen its initial stake multiplied several times.

More and more often, management teams are advised by a specialised consultancy firm and lawyers for the implementation of these management packages.

Employees are also key to the success of an LBO, which is why some LBO funds have made it a practice to give a small part of their capital gain (usually 2–5%) to employees.

Section 47.3 LBOS AND FINANCIAL THEORY

Experience has shown that LBOs are often done at the same price or at an even higher price than what a trade buyer would be willing to pay. Yet the trade buyer, assuming they plan to unlock industrial and commercial synergies, should be able to pay more. How can we explain the widespread success of LBOs? Do they create value? How can we explain the difference between the pre-LBO value and the LBO purchase price?

At first, we might be tempted to think that there is value created because increased leverage reduces tax payments. But the efficient markets hypothesis casts serious doubts on this explanation, even though financial markets are not, in reality, always perfect. To begin with, the present value of the tax savings generated by the new debt service must be reduced by the present value of bankruptcy costs. Secondly, the arguments in Chapter 33 have led us to believe that the savings might not be so great after all. Hence, the attractions of leverage are not enough to explain the success of the LBO.

We might also think that a new, more dynamic management team will not hesitate to restructure the company to achieve productivity gains and that this would justify the premium. But this would not be consistent with the fact that the LBOs that keep the existing management team create as much value as the others.

Agency theory provides a relevant explanation. The high debt level prompts shareholders to keep a close eye on management. Shareholders will closely monitor operating performance and require in-depth monthly reporting. Management is put under pressure by the threat of bankruptcy if the company does not generate enough cash flow to rapidly pay down debt. At the same time, managers systematically become – either directly or potentially – shareholders themselves via their management package, so they have a strong incentive to manage the company to the best of their abilities.

Kaplan has demonstrated through the study of many LBOs that their operating performance, compared with that of peer companies, is much better (cash flow generation, return on capital employed) and that they are able to outgrow the average company and create jobs. This is one example where there is a clear interference of financial structure with operating performance.

LBO transactions greatly reduce agency problems and in so doing create value. Their corporate governance policies are different from those of listed groups and family companies, and in many cases are more efficient.

LBOs give fluidity to markets, helping industrial groups to restructure their portfolio of assets. They play a bigger role than IPOs, which are not always possible (equity markets are regularly shut down) or realistic (small and medium-sized companies in some countries are, in fact, practically banned from the stock exchange).

Section 47.4 THE LBO MARKET: A WELL-ESTABLISHED MARKET

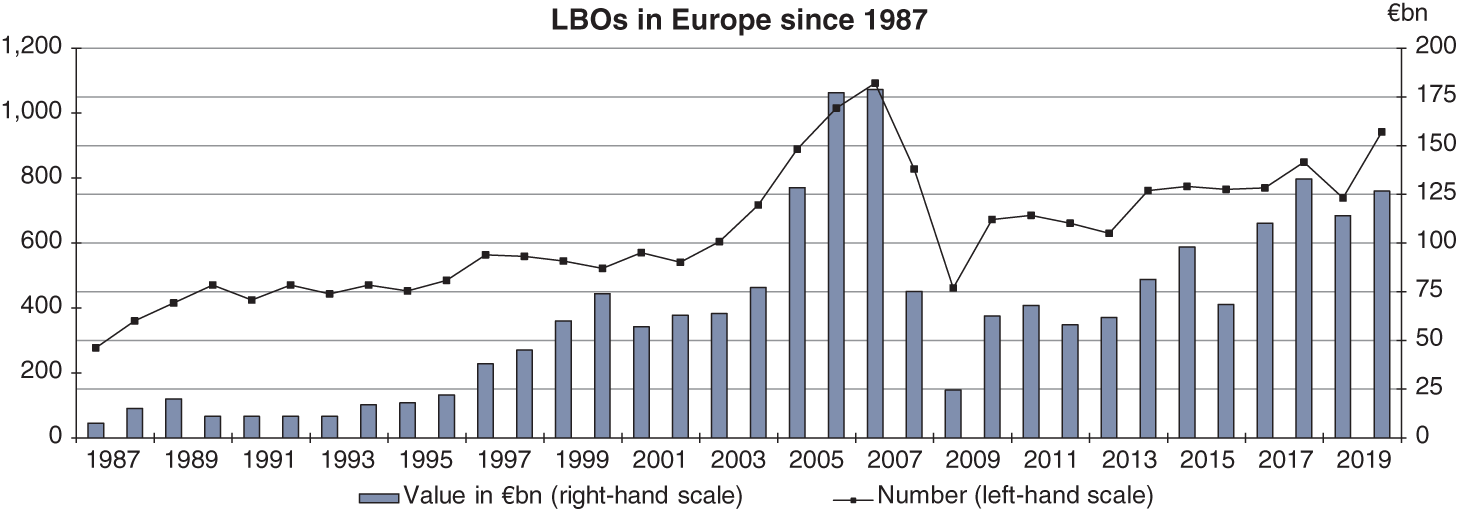

While LBOs have grown considerably in Europe since the 1980s, this growth has been highly cyclical. It is highly dependent on lenders' appetite for risky debt, without which LBOs cannot take place, and on economic conditions that suggest that the debt contracted will be repaid by the cash flows generated and/or the resale of the company under LBO. There is therefore an alternation, with the regularity of a metronome, between phases of expansion (late 1990s, 2003–2007, 2014–2019) and contraction (early 1990s, 2000–2003, 2008–2013, 2020).

Source: Data from CMBOR / Equistone Partners Europe, Mergermarket

The debt to EBITDA ratios are reduced and inflated, covenants are more or less strict, A tranches (repaid on a straight-line basis and not at the end) provide a more or less significant part of the debt repayment, making LBO financing more like asset financing (when the vast majority of the repayment comes from the resale of the company under LBO), or rather cash flow financing, which is what they were supposed to be when LBOs were invented.

In 2020, as in 2008–2013, companies under LBO suffered the consequences of a decline in activity coupled with high debt levels. Nevertheless, the rapid recovery of activity in 2021 gives reason to hope that, in most sectors, equity will be sufficient to absorb the business losses of 2020.

SUMMARY

QUESTIONS

ANSWERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES

- 1 We have based this example on publicly available information, and for some of the figures have either simplified the reality or made some estimates. It should be considered as illustrative and does not reflect the reality or the exact state of the company.

- 2 Assuming 100% payout.

- 3 Assuming tax consolidation treatment.

- 4 Pension funds, insurance companies, banks, sovereign wealth funds.

- 5 Just before the LBO market ground to a sudden halt.

- 6 Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation. For more, see Chapter 3.

- 7 Section 20.1.

- 8 Of small or medium size; Fives is an example.