6

Preventing

Objections

During a visit to the training center of a leading multinational company, I was invited to watch some sales training in progress. Instead of choosing the Advanced Systems Selling class, as my hosts had perhaps expected, I asked instead if I could sit in on a typical basic-skills program for new salespeople. Entering quietly at the back of the room, I looked around. The students all had that unnatural attentive cleanliness that goes with being new to sales. Their instructor, recently promoted from the field, was launching with great vigor into his favorite topic—objection handling. You couldn’t have imagined a more typical scene. It could have been Day 2 of any basic sales-training program in any large corporation.

“The professional salesperson,” the instructor began, “welcomes objections because they are a sign of customer interest. In fact, the more objections you get, the easier it will be for you to sell.” The class, duly impressed, wrote this down. Meanwhile I groaned behind my mandatory visitor’s smile. Here was yet another new generation of salespeople at the receiving end of one of the most misleading myths in selling. Still, as a visitor it would have been improper for me to comment, so I continued to smile through an hour of objection-handling techniques until the coffee break.

During the break, I talked with the instructor. “Did you believe what you were saying in there,” I asked, “that stuff about the more objections, the easier to sell?”

“Yes,” he replied. “If I didn’t believe it, I wouldn’t be teaching it.”

I hesitated. Clearly the instructor and I had opposite views about objection handling. It would have been easier to drop the subject, but he’d been kind enough to let me into his class, so I felt I owed him something in return. I asked, “You’ve been a successful sales performer for several years, haven’t you?”

“Yes,” he replied with some pride. “I’ve been with the company five years and I’ve made President’s Club for the last three.”

“Look back at your own sales experience,” I urged him. “Five years ago, when you were new, did you receive more or fewer objections from your customers than you’re getting now?”

He thought for a moment. “More, I guess.” Then, as he remembered back, he added, “You know, in the two years when I was new, I seemed to get objections all the time.”

“So in those first two years when you were facing all those objections, did you have good sales figures?”

“No,” he said uncomfortably. “In fact, my sales weren’t too good until my third year with the company.”

Pressing the point, I asked him, “Then you did a lot better in that third year?”

“Yes, that was the year I first made President’s Club.”

“And how about objections? It sounds as if you had more objections in your unsuccessful years. How does that tie in with what you said in class about the more objections, the more successful the call will be?”

He considered the point for a while and said, “You’re right. When I look back, I faced many more objections when I was unsuccessful. Perhaps I’m teaching the wrong message.”

I had to admire him. Most people—given the astonishing human capacity for dismissing unwanted evidence—would have dodged the issue and held to their initial position. But the class was reconvening and I had to finish my tour of the facility, so I didn’t have time to talk more with the instructor about objection handling. If we’d had more time, I would have told him:

![]() Objection handling is a much less important skill than most training makes it out to be.

Objection handling is a much less important skill than most training makes it out to be.

![]() Objections, contrary to common belief, are more often created by the seller than the customer.

Objections, contrary to common belief, are more often created by the seller than the customer.

![]() In the average sales team, there’s usually one salesperson who receives 10 times as many objections per selling hour as another person in the same team.

In the average sales team, there’s usually one salesperson who receives 10 times as many objections per selling hour as another person in the same team.

![]() Skilled people receive fewer objections because they have learned objection prevention, not objection handling.

Skilled people receive fewer objections because they have learned objection prevention, not objection handling.

To explain these findings, I’ll have to go back to the discussion of Features, Advantages, and Benefits in Chapter 5. You’ll remember the definitions of these three behaviors and their links to success in sales of different sizes (Figure 6.1). One of my colleagues, Linda Marsh, carried out some correlation studies to check whether there are statistically significant links between each of these behaviors and the most probable responses they produce from customers. For example, when sellers use a lot of Features in calls, do customers respond in a different way than in calls where fewer Features are used? She discovered that Features, Advantages, and Benefits each produce a different behavioral response from customers (Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.1. Features, Advantages, and Benefits.

Figure 6.2. Most probable effects of Features, Advantages, and Benefits on customers.

Features and Price Concerns

Customers are most likely to raise price concerns in calls where the seller gives lots of Features. Why is this? It seems that the effect of Features is to increase the customer’s sensitivity to price. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing if you happen to be selling low-cost products that are relatively rich in Features.

Consider the psychology of the advertisement shown in Figure 6.3. This features-rich product is being sold in a way that works well with cheaper goods. You can imagine a television commercial: “We give you multiplication, division, subtraction...and what do you think that’s worth? Well, don’t answer yet because you also get mark-up and markdown percentages—which is something you don’t usually find on watches 10 times the price. And we also give you...” Throughout history, using Features this way has helped sell lower-priced goods. Why? Because Features increase price sensitivity. By listing all the Features, the customer comes to expect a higher price. When the product turns out to be much cheaper than its competition, the increased price sensitivity causes the buyer to feel extra positive about the lower price tag.

Figure 6.3. A low-cost product rich in features.

I chose a watch example, rather than an industrial product, because there’s something unique about watches. In no other market that I can think of is there such an enormous price difference between competitors.

Now consider the advertisement shown in Figure 6.4. This watch is almost 100 times as expensive as the one in Figure 6.3. Do you think you’d be more likely to buy this expensive watch if there was a list of Features down the side of the advertisement to help persuade you? Not on your life! With top-of-the-market products, the price concern created by Features will make people less likely to buy. A list of Features would probably make you ask yourself questions about whether the expensive watch was worth it.

Figure 6.4. A high-cost product. Listing features is a negative.

Too Many Features: A Case Study

The relationship between Features and price concerns isn’t just a theoretical point that applies only to advertisers. It has clear implications for sales strategy. A major U.S.-based multinational corporation once called us in to help it with a problem. The corporation had been facing tough Japanese competition in its primary marketplace, particularly at the lower end of its product range. The Japanese products were richly featured and, as you might expect, somewhat less expensive than its own machines. As market share began to erode, the corporation looked for alternatives to price cutting. One attractive possibility was to introduce a new product with more Features that could compete directly with the Japanese machines. Such a machine would still be a little more expensive, but because of its added Features, it would provide a much stronger marketplace offering.

But who would sell this new product? The corporation decided to recruit part of the sales force from the competition. After all, nobody knew as much about how to sell these richly featured machines as the people who’d been successful sellers for the Japanese competitor. It seemed, on the face of it, a plausible strategy—recruiting experienced sellers while simultaneously weakening the competition by raiding its best people. The corporation’s agents approached those salespeople who’d been very successful selling the cheaper Japanese machines and succeeded in recruiting some of the competitor’s top people.

Unfortunately, these new people’s sales results were deeply disappointing. The competition’s superstars performed no better than the existing sales force. While trying to discover what was going wrong, I talked with several of the people recruited from the competition and found them puzzled and dejected at their sudden fall from success. “It’s price,” they explained. “The product’s too expensive; we get price objections all the time.” And they were right. When we traveled with them on calls, we found that the number of price objections they received from customers was 30 percent higher than for the rest of the sales force who were selling the same product. Why? We couldn’t write it off as pure coincidence when two sections of a sales force selling an identical product received different levels of price objections from their customers.

The answer lay in their use of Features. While selling for the cheaper competitor, these salespeople had developed a selling style very high in Features. This was very successful because, as we’ve seen, Features increase customers’ price concerns. But because their product was cheaper, the price concern worked to their advantage. Now that they were selling for a more expensive competitor, the high level of Features they were giving worked against them. Their Features increased price concern and, because their product was more expensive, this turned customers toward the cheaper competitor. I presented our findings to the V.P. of Sales for the division. As he wryly remarked, “Right now, they seem to be doing a better job of selling for our competition than when our competition employed them.” How could we help? Not, I suggested, by teaching them how to handle price objections. That was just a symptom. It would be more effective to treat the cause and help these new people adopt a selling style more appropriate to a top-of-the-market product. So we retrained them in SPIN questioning techniques so that they could use a high-Benefits style. As a result, their sales increased, price objections dropped, and the price issues were soon forgotten.

Treating Symptoms or Treating Causes?

Let me introduce a theme that I’ll come back to several times in this chapter. Curing a selling problem, just like curing a disease, rests on finding and treating the cause rather than the symptoms.

When I was 9 years old I lived in Borneo. A friend of my own age warned me that there was a typhoid epidemic in the village. All that either of us knew about typhoid was that it caused a burning fever. “But I won’t catch it,” he assured me; “I’m eating a lot of ice cream to keep cool.” I followed his example—and caught typhoid from infected ice cream. One of the few things I remember clearly about my month seriously ill in the hospital was my father explaining to me the differences between symptoms, such as a high temperature, and causes, such as the nasty little bacterium Salmonella typhosa that loves to lurk in ice cream.

Perhaps this episode made me unduly sensitive to treating symptoms when you should be watching out for causes. But just suppose we’d run a program to teach those salespeople clever answers to price objections. Would we have achieved anything? I think not. The customer’s price concern was just a symptom. The cause was giving too many Features. Teaching objection-handling skills would do no more to prevent price concerns than eating ice cream would prevent typhoid.

Advantages and Objections

Perhaps the most fascinating of the links that Linda Marsh found is the strong relationship between Advantages and objections. You’ll remember that Advantages are statements that show how products or their Features can be used or can help the customer—statements that many of us have been trained to call “Benefits.” Chapter 5 showed that Advantages have a positive effect on small sales but a much less positive effect when the sale grows larger, and Linda’s discovery offers a partial explanation of this. Advantages create objections—and this is one reason why they are poorly linked to success in the large sale.

To help understand the link between Advantages and objections, consider the following extract from an actual sales call. I’ve edited out references to the company and I’ve cut the length of some statements; otherwise, this exact sequence of behaviors happened in a call we recorded in Dallas in September 1981. The product being sold is a word processor.

SELLER: (Problem Question) Does all this retyping waste time?

BUYER: (Implied Need) Yeah, some. But there’s not so much of it here, not like in Fort Worth.

SELLER: (Advantage) Here’s where our word processors would be a real big help because they’d eliminate that retyping for you.

BUYER: (objection) Look, we retype stuff, sure. But you won’t get me paying for fancy $15,000 machines just to cut down on some retyping.

SELLER: (Advantage) I understand you, but the labor costs of retyping can climb out of sight. A big plus of word processors is that they save you money by making your people more efficient.

BUYER: (objection) We’re very efficient right now—and if I wanted to do better on efficiency I can think of 16 ways without new word processors. I’ve two xxx word processors there in the back office. Nobody much knows how to use them. They give trouble, just trouble.

SELLER: (Problem Question) Those xxx machines are hard for your people to use?

BUYER: (Implied Need) Yes, it’s quicker to type it out by hand—doing it the old way.

SELLER: (Advantage) We really can help you there. Our yyy machines use a screen, so people can see exactly what they’re doing. That’s a lot better than your old xxx’s where you’ve got to remember things like format codes—which we prompt automatically, so that our machine can be used much more easily.

BUYER: (objection) Know what? Some of the ladies working here get uptight about a typewriter with a correcting ribbon. Screen? It’d just confuse the hell out of them. I’d end up with more mistakes than I’m getting now.

SELLER: (Problem Question) You’re getting too many mistakes?

BUYER: (Implied Need) Some. Well, no more than most offices, but more than I like.

SELLER: (Advantage) Tests show that with the full-screen editing and error correction we offer, your error rates would drop by more than 20 percent if you used our machines.

BUYER: (objection) Yeah, but it’s not worth all that hassle just to get rid of a few typos.

What’s happened here? The first thing you’ll notice is that every Advantage is followed by an objection. Of course, I’ve chosen this extract to illustrate my point, for objections don’t always follow Advantages the way they do in the example I’ve picked here. Sometimes the seller will use an Advantage that brings a favorable response from the customer. But from our research, objections are a more likely response than any other buyer behavior (Figure 6.5).

Figure 6.5. Creating objections.

The next thing to notice about this example is the characteristic sequence of behaviors: Problem Questionllmplied Needlobjection. We found this sequence happening over and over again in unsuccessful calls. Let’s look more closely at what’s going on.

As you can see, the fundamental problem that’s causing the objection is that the seller offered a solution before building up the need. The buyer doesn’t feel that the problem has enough value to merit such an expensive solution. Consequently, when the seller gives the Advantage, the buyer raises an objection.

This explains why Advantages have a more positive effect in small sales. If the word processor had cost $15 instead of $15,000, the buyer would probably have reacted differently. It’s certainly worth $15 to eliminate retyping. But $15,000? That’s a different matter.

Back to Symptoms and Causes

How would you help the seller in our example? It’s tempting to suggest that because she is receiving so many objections, what she needs is better objection-handling skills. So, for example, we could teach her principles of objection handling—the classic techniques of acknowledging, rephrasing, and answering. Or we could give her specific help with the common objections that customers raise by showing her what to say when customers raise such typical objections as:

Your word processors are too expensive.

Word processors are hard to use.

My people would be resistant to word processors.

Word processors are more hassle than they’re worth.

Either of these options would help her handle future objections better. But are we treating the symptom or the cause? In each case in the example, the objection arose because the seller hadn’t built sufficient value before offering solutions. Teaching her how to handle objections treats the symptom, but it doesn’t alter the cause. The fundamental selling disease—jumping in too soon with solutions—remains malignant and untreated.

The Cure

If objection handling just treats a symptom, how would we set about a complete cure? This is where the SPIN Model comes in. By teaching her to probe in a way that builds value, we can prevent the objection from arising in the first place. Let me show you what I mean, using the final objection in the example. First let’s examine why the customer raised the objection in the first place.

SELLER: (Problem Question) You’re getting too many mistakes?

BUYER: (Implied Need) Some. Well, no more than most offices, but more than I like.

SELLER: (Advantage) Tests show that with the full-screen editing and error correction we offer, your error rates would drop by more than 20 percent if you used our machines.

BUYER: (objection) Yeah, but it’s not worth all that hassle just to get rid of a few typos.

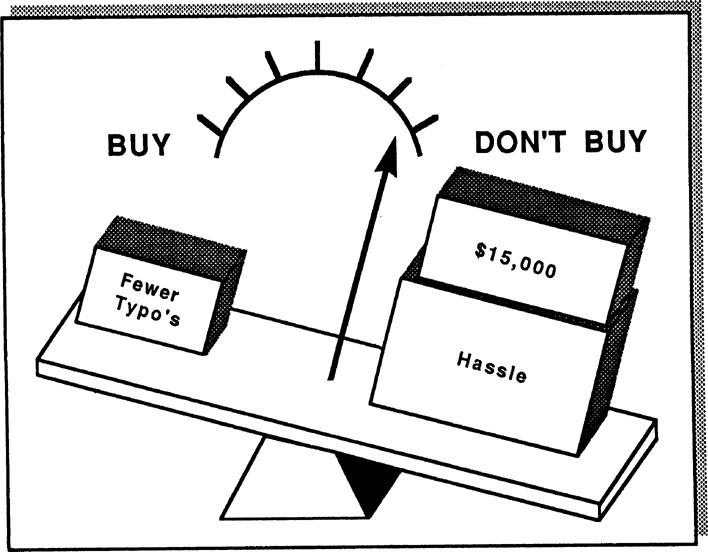

The customer has raised the objection because he doesn’t perceive sufficient value from reducing the error rate. If you could draw a value-equation diagram to show what was going on in the customer’s mind, it would probably look like the one in Figure 6.6. The hassle greatly outweighs the value of eliminating a few mistakes, so the customer makes a negative judgment and raises an objection. Even the best objection-handling skills can’t alter the fact that the seller has offered a solution without first building value.

Figure 6.6. How the customer sees it.

Let’s look at how a more skilled person would handle the same situation:

SELLER: (Problem Question) You’re getting too many mistakes?

BUYER: (Implied Need) Some. Well, no more than most offices, but more than I like.

SELLER: (Implication Question) You say “more than you’d like. Does this mean that some of those mistakes are causing you difficulties in documents you send out to clients?

BUYER: Sometimes that’s happened, but not often, because I proofread all important documents carefully before I send them out.

SELLER: (Implication Question) Doesn’t that take up a lot of your time?

BUYER: Too much. But it’s better than letting a document go out with a mistake—particularly if it’s a mistake in the figures that go out to a client.

SELLER: (Implication Question) Why would that be? Are you saying that a mistake in the figures would lead to more serious consequences with clients than a mistake in the text would?

BUYER: Oh yes. We could lose a bid, or commit ourselves to an uneconomic contract—or even just come across to clients as sloppy. People judge you on things like that. That’s why it’s worth a couple of hours a day proofreading when there’s other things I should be doing.

SELLER: (Need-payoff Question) Suppose you didn’t have to spend that time proofreading. What could you do with the time you saved?

BUYER: Well, I could give some time to training my office people.

SELLER: (Need-payoff Question) And this training would lead to improved productivity?

BUYER: Oh, very much. At the moment, you see, people don’t know how to use some of the equipment here—that graph plotter for example—so they have to wait until I’m free to do it.

SELLER: (Implication Question) So the time you’re spending in proofing also forces you to become a bottleneck for other people’s work?

BUYER: Yes. I’m badly overloaded.

SELLER: (Need-payoff Question) Then anything that reduced the time you’re spending in proofing wouldn’t just help you, it would also help the productivity of others?

BUYER: Right.

SELLER: (Need-payoff Question) I can see how by reducing proofreading you could ease the present bottleneck. Is there any other way that having fewer mistakes in documents would help you?

BUYER: Sure. People here hate retyping. It might be a plus in terms of their motivation if fewer mistakes meant less time spent in retyping.

SELLER: (Need-payoff Question) And presumably less time in retyping would also bring cost savings?

BUYER: You’re right. And that’s something I need to do.

SELLER: (summarizing) So it seems that the present level of mistakes is leading to expensive retyping, which creates a motivation problem with your people. If mistakes, particularly in figures, get out to your clients, it can be very damaging. You’re trying to prevent that at the moment by spending 2 hours a day proofing all key documents. But that’s turning you into a bottleneck, reducing everyone’s productivity and preventing you from putting time into training your staff.

BUYER: When you put it that way, those mistakes in documents are really hurting us. We can’t just ignore the problem—I’ve got to do something about it.

SELLER: (Benefit) Then let me show you how our word processor would help you cut mistakes and reduce proofing...

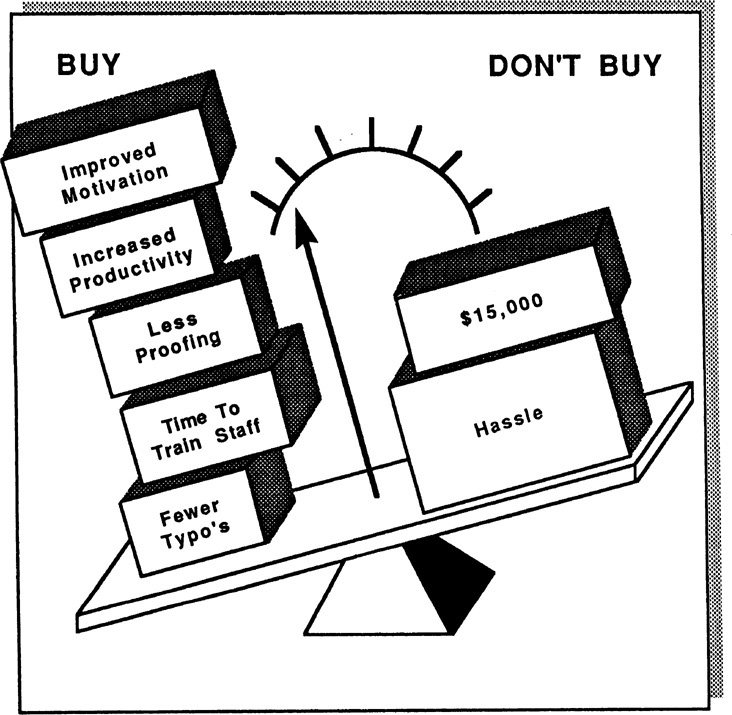

If we were to reexamine the customer’s value equation now, it would probably look like the one in Figure 6.7.

Figure 6.7. The customer develops a new point of view.

Now the cost and hassle are more than counterbalanced by the value the seller has created through the use of Implication and Need-payoff Questions. It’s a much more effective piece of selling because we’ve attacked the cause of the objection. As a result, the objection doesn’t even arise. Objection prevention turns out to be a superior strategy to objection handling.

Objection Prevention: A Case Study

I can imagine people reading this and saying to themselves, “Yes, it all sounds very plausible when Rackham’s making up examples that suit his case, but I’m not sure it holds up in the real world.” As a further piece of evidence, then, I’d like to share with you one of the most fascinating little investigations I was ever involved with.

The company was a well-known high-tech corporation whose personnel research staff had been investigating sales behavior in one of its divisions based in the southern United States. We had encouraged the research staff to use the behavior-analysis method of counting how often key seller and customer behaviors occurred during sales calls, and they had come up with a curious finding. The average sales team in the division consisted of eight salespeople. Now purely in terms of statistical probabilities, you’d expect that these eight people, each selling the same product to the same size of customer and with the same competitors, would each face approximately the same number of objections per selling hour. Not so. There was an enormous difference in the number of objections faced by individual salespeople. In the average team they often found one salesperson having to face 10 times as many objections per selling hour as other people from the same team.

The research staff didn’t know about our work on the links between Advantages and objections. Naturally, they drew the obvious conclusion: The people who were receiving so many objections must need training in objection handling. They asked us for advice. One quick look at their data told us what we needed to know. We picked the behavior-analysis figures for 10 people who were each receiving very high numbers of objections and who were clearly candidates for objection-handling training. In all 10 cases, these people were higher than average in the number of Advantages they used in their calls.

I persuaded the company to try a bold experiment. “What I’d like to do,” I explained, “is to train these people in objection prevention. I think we can design a program which doesn’t even mention the word objection but which will do more for these people than the best objection-handling training ever could.” The company agreed. We chose eight salespeople who—from the behavior-analysis figures—had each received an unusually high level of objections from customers. As we’d promised, our training didn’t say anything at all about objections or objection handling. Instead, we taught the eight people to develop Explicit Needs with the SPIN Model and then to offer Benefits.

After the training, the company’s researchers went out with the eight to count the number of objections they were now receiving in calls. The average number of objections per selling hour had fallen by 55 percent. I’d draw two conclusions from this little study:

![]() It confirms that the best way to handle objections is through prevention. Treat the cause, not the symptom.

It confirms that the best way to handle objections is through prevention. Treat the cause, not the symptom.

![]() Notice that our training didn’t prevent objections completely.

Notice that our training didn’t prevent objections completely.

There will always be objections that arise because the customer has needs your product can’t meet or because a competitor has a clear product superiority. These “true” objections are facts of life, and no objection-prevention technique can do anything to stop them from being raised. However, what we were able to show in this case was that objections can be cut by more than half by using the SPIN behaviors to build value.

The Sales-Training Approach to Objections

Traditional sales training actually teaches people to create objections, then teaches them techniques for handling the objections they’ve inadvertently created. This is because the selling-skills models in every major sales-training program we’ve reviewed have been based on the small sale. As we’ve seen, in small sales a high level of Advantages can be successful because there’s less need to build value before offering solutions—but in larger sales Advantages don’t have this positive impact. (It’s important to remember that we’re using the term Advantage to cover any statement that shows how your product or service can be used or can help the customer; in other words, what we’re calling an Advantage is what most sales training calls a Benefit.)

It’s my hope, as training designers begin to understand that larger sales need different skills, that we’ll see an end to the kind of training that encourages salespeople to give a lot of Advantages. The heavy use of Advantages—which is what most training recommends—is the cause of more than half of the objections that customers raise. But are objections necessarily bad? Some sales-training programs and many sales trainers, such as the instructor I described at the first of this chapter, teach that objections are positively linked to success and that the more you get, the better. If that’s true, then preventing objections could actually hurt your selling. What does the evidence tell us?

We carried out a study to find out whether objections were really “sales opportunities in disguise,” as one training program put it. We counted the number of objections raised by customers in a sample of 694 calls collected from an international sample in a large business-machines corporation. Figure 6.8 shows the results.

Figure 6.8. Objection levels and call success.

As you can see, the higher the percentage of objections in the customer’s behavior, the less likely that the call will succeed. If objections are sales opportunities in disguise, then this study suggests that their disguise must have been created by a master in camouflage. No, make no mistake about it, the more objections you get in a call, the less likely you are to be successful. It’s a comforting myth for trainers to tell inexperienced salespeople that professionals welcome objections as a sign of customer interest, but in reality an objection is a barrier between you and your customer. However skillfully you dismantle this barrier through objection handling, it would be smarter not to have created it in the first place.

Benefits and Support/Approval

The most positive relationship to emerge from Linda Marsh’s study of Features, Advantages, and Benefits is the strong link between giving Benefits and receiving expressions of approval or support from customers. She found that the more Benefits the sellers gave, the more approving statements their customers made. This isn’t a surprising finding. After all, Benefits—as we define them—involve showing how you can meet an Explicit Need that the customer has expressed. Unless the customer first says, “I want it,” you can’t give a Benefit. It’s no wonder that customers are most likely to express approval when you show you can give them something they want.

Objection Handling versus

Objection Prevention

At its most basic, what I’ve suggested in this chapter is that the old objection-handling strategies, which encourage the seller to give Advantages, are much less successful in the larger sale than objection-prevention strategies, where the seller first develops value using Implication and Need-payoff Questions before offering capabilities (Figure 6.9).

Figure 6.9. Objection handling or objection prevention?

When I was new to selling I thought that, next to closing, objection-handling skills were the ones most crucial to sales success. Looking back, I can now see that my concern was motivated by the large number of objections I was facing from my customers. I didn’t ask myself what caused the objections—but just knew that there were lots of them, so I’d better improve my objection handling. I now understand that the majority of objections I faced were only a symptom caused by poor selling. By improving my probing skills, I’ve become more successful at objection prevention—and this has certainly helped me sell more successfully. I still get objections, of course, for in selling there will always be the potential for a genuine mismatch between customer needs and what a seller can offer. So objection-handling skills will always have a part to play in my calls. But the reason I sell better now isn’t better objection-handling skills, it’s that I’m less likely to create unnecessary objections.

Preventing Objections from Your Customers

If you’re receiving more objections from customers than you’d like, think about which is symptom and which is cause. Could it be that objections are just a symptom you’ve caused by offering your solutions too soon in the call? Try putting extra effort into effective needs development, using Implication and Need-payoff Questions. If you can build the value of your solutions, then you’re much less likely to face objections. As many hundreds of salespeople we’ve trained will testify, good questioning skills will do more to help you with objections than any objection-handling techniques ever could.

Of course, you’ll always get some objections, especially when your product doesn’t meet a customer’s needs. However, here are two sure signs that you’re getting unnecessary objections that can be prevented by better questioning:

1. Objections early in the call. Customers rarely object to questions—unless you’ve found a particularly offensive way to ask them. Most objections are to solutions that don’t fit needs. If you’re getting a lot of objections early in the call, it probably means that instead of asking questions, you’ve been prematurely offering solutions and capabilities. The cure is simple enough: Don’t talk about solutions until you’ve asked enough questions to develop strong needs.

2. Objections about value. If most of the objections you receive raise doubts about the value of what you offer, then there’s a good chance that you’re not developing needs strongly enough. Typical value objections would be “It’s too expensive,” “I don’t think it’s worth the trouble of changing from our existing supplier,” or “We’re happy with our existing system.” In cases like these, customer objections tell you that you haven’t succeeded in building a strong need. The solution lies in better needs development, not in objection handling. Particularly if you’re getting a lot of price objections, cut down on the use of Features and, instead, concentrate on asking Problem, Implication, and Need-payoff Questions.