Chapter 17

To Bundle or Not to Bundle: Is That Really the Question?

The very question of whether a company should bundle or unbundle its products implies that at any given point in a product's life cycle, there is an ideal way to package the various products, product components, and services in a portfolio into appealing offers for customers.

The easiest association with bundling for most people is the combo meal they can order at a fast-food restaurant: a sandwich, a side dish, and a beverage, at a lower combined price than the items cost separately. This is an example of ‘mixed bundling’, which means that a customer can also purchase one or more of the components of the bundle individually. The classic physical music formats such as the compact disc and vinyl LP are also familiar bundles, but they exemplify ‘pure bundling’. In contrast to mixed bundling, a pure bundle forces customers to buy the whole package – in this case, the whole album – even if they only want one or two songs. With some exceptions, the individual components are not available for sale separately.

So how should a company determine those ideal combinations of products and services in a portfolio and then sell them to customers? In the spirit of the Visible Game, companies can cite numerous practical and objective reasons to create bundles or break them up. These reasons include logistical and manufacturing efficiencies, easier and clearer communication, and the potential for better financial performance. Even so, there is also enormous untapped and overlooked potential for bundling and unbundling in the Invisible Game. In the rest of this chapter, we will highlight some of these influencing factors behind the art and science of bundling, before showing how companies can play the Invisible and Visible Games simultaneously to find – and adjust – their own balanced offerings with confidence. Some of the same principles apply to unbundling, and we will conclude the chapter with some of the insights that can make unbundling a more successful strategy.

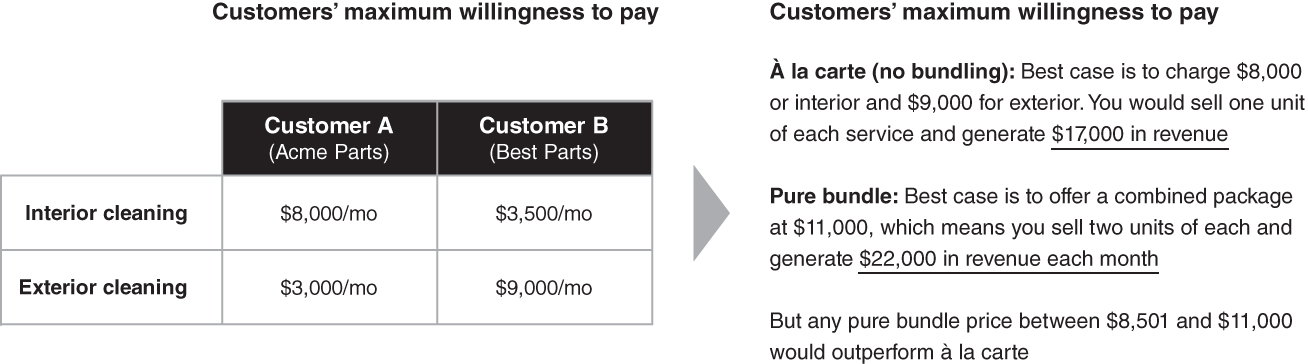

Bundles do make buying decisions easier than à la carte offerings because buyers need to weigh fewer options than they would if they need to mix-and-match their own solution from scratch. Bundles are especially effective when they take advantage of preference reversals. Imagine a portfolio of two services, interior cleaning and exterior cleaning. The customer Acme Parts values the interior cleaning at $8,000 per month and the exterior cleaning at only $3,000 per month, while the customer Best Parts is basically the opposite. They value the interior cleaning at $3,500 per month and the exterior cleaning at $9,000 per month. In such a situation, it is impossible to set à la carte prices in a way that would generate more revenue – and more volume – than a pure bundle would generate. Figure 17.1 shows why.

The power of bundling holds even when the bundles are more complex and diverse than the straightforward example shown in Figure 17.1. But as you might imagine, when you have several potential products or services to include in a bundle, which ones you choose – and how many – will make a significant difference in how customers respond psychologically. We offer two caveats if you plan to bundle or unbundle products and services.

Figure 17.1 Pure bundling outperforms à la carte pricing or mixed bundling when customer preferences vary widely

‘Less is better’: On a purely objective basis, finishing second is better than finishing third. It would therefore make sense that someone who finishes second should be happier with their performance than someone who finished third. But one study of Olympic medal winners showed the opposite effect: bronze medal winners tended to be happier with their medal than silver medal winners.1 In essence, they were happier with less.

Likewise, it would make sense for someone to pay more for an eight-ounce serving of ice cream than a seven-ounce serving of exactly the same ice cream. But that is not true when the seven-ounce serving is crammed into a small container, while the eight-ounce serving comes in a ten-ounce cup that clearly leaves empty space at the top. The respondents in that study were willing to pay more for less.2

To understand why people make these clearly counterintuitive ‘less is more’ decisions, think back to our discussions of relativity in Part I. It is hard for people to make judgments unless they have a reference point or a pre-calibrated scale. One reason for this is the evaluability hypothesis, which states that when we evaluate something in isolation, our evaluations are often influenced by how easy attributes are to evaluate rather than how important the attributes are. Whenever we cannot make a direct relative judgment, our attention falls either on things we can easily observe and process, or on what we aren't getting in the deal rather than what we are getting. The athletes who won bronze are happy, because people who finish fourth at the Olympic Games do not get medals. But the athletes who won silver are disappointed, because someone else won gold.3 Similarly, the customer at the ice cream shop feels rewarded when she sees seven ounces overflowing in a small cup, but feels cheated when the ten-ounce cup is not filled, even when the latter container has roughly 15% more ice cream than the former.4

Descriptive language is sufficient to alter someone's perception toward a lesser option, in the absence of visual or other sensory cues. Imagine that you are trying to select the final runner to represent your firm in a team 5k run to benefit a local charity.

‘Well, we had a practice run yesterday’, one of your colleagues says. ‘Kerry finished second, but Kris came in next to last.’ Based solely on that information, you would probably lean toward choosing Kerry to complete your team. What your colleague neglected to tell you, however, is that Kerry and Kris were the only two competitors in that practice run yesterday. Kerry finished second and last. Kris finished first, but technically speaking, also finished next to last.5

The lesson for bundling is that buyers will be influenced by the relative value of the individual components of a bundle. An additional product or service that exceeds expectations or seems disproportionately good will enhance a bundle, while an item that falls short of expectations will detract from the bundle's total value, even if that item is worth more in absolute terms.

University of Chicago behavioural science professor Christopher Hsee conducted an experiment that drives home that point. Respondents placed a higher value on a complete 24-piece set of dinnerware than they did on a collection of 31 pieces of dinnerware – including the original complete set, plus a few other pieces and some broken ones. The self-contained yet smaller set was more appealing than the larger set that included additional useful items and some inferior or unusable ones.6

Don't bundle very expensive things with cheap things: One additional lesson from those studies is that a seller should not bundle expensive items with very cheap items. The ghost of homo economicus would consider that statement to be illogical, because even cheap things add incremental value. How can adding value to a package – even a small amount – reduce the total value of the package?

Let's say you have a choice between buying a home gym and buying a gym membership. Wouldn't the home gym be more attractive if it came with a fitness DVD? Northwestern's Alexander Chernev and Pepperdine University's Aaron Brough tested that idea in five separate experiments and revealed that ‘combining expensive and inexpensive items can lead to subtractive rather than additive judgments, such that consumers are willing to pay less for the combination than for the expensive item alone.’7 In the case of the home gym and the gym membership, for example, the number of respondents who chose the home gym fell by 31% when the home gym came with the fitness DVD.8 This occurs because people bucket the components of the bundle into broad qualitative categories – expensive, inexpensive, cheap – and then come up with an unweighted average of those categories. In the example of the gym, the equipment (expensive) and the DVD (cheap) average out to a net relative valuation that is less than the gym membership.

The ultimate test of a bundle is that the combination of products and services offers an advantage to both your customer and you. Just because you can theoretically group a few products together does not mean that the resulting combination will pass that test. The caveat here is that bundles are neither dumping grounds nor escape hatches for products you struggle to sell.

Bundling done well makes it easier for buyers to decide. It also enhances the differentiation of your offerings, by reducing the buyer's ability to make direct comparisons with competitive offerings and base their decisions solely on price. Bundling also creates opportunities to upsell. On the financial side, you should be aware that bundling can reduce your overall margin percentage, even though it can substantially increase your profits in absolute terms. The higher your fixed costs are, however, the less dramatic the margin percentage impact will seem.

Unbundling: The ‘core’ and ‘cost’ questions

It is tempting to think of bundling and unbundling as two sides of the same coin or two opposing directions along the same spectrum. But this is only partially true. The determining factors in a decision to unbundle a product or service are whether the offering in question is a core or non-core part of your business, and how volatile the costs of the product or service are.

We will start with the question of core versus non-core. In general, that is a fundamental strategic question far beyond the scope of this book. For the purposes of influencing buying decisions – and for unbundling in particular – there is a straightforward and practical way to distinguish between core and non-core. The latter encompasses those products and services that you procure and consume yourself but add no proprietary value. Mundane examples include packaging, shipping, storage, and third-party services such as legal support. With such clarity, we see no issue with price unbundling, which means that it often makes sense to charge separately and appropriately for shipping, out-of-pocket costs for a service call, or off-the-shelf materials.

Unbundling also helps a company cope with wide variations in cost to serve. These costs can be out-of-pocket costs, such as third-party costs to ship to remote or unplanned destinations, or inconvenience costs, such as when a client orders less than a truckload, orders outside pre-determined periods, orders containing custom sizes, or otherwise causes an unanticipated disruption to your operations. Ideally, you shouldn't be incurring costs unless those costs help you generate revenue and earn an appropriate margin. When a customer's behaviour causes you to incur extra costs, you can offset that burden by connecting those unexpected or above-and-beyond expenses to an additional service fee.

Unbundling also makes sense when you have features that are truly optional. You are under no obligation to offer all-inclusive packages to all customers, when it is more convenient and more practical to let customers decide what extras they need. Similarly, unbundling is an effective way to test the viability of new add-on services or enter new markets. In these situations, having more levers can help you gain greater trial and access than you would if you rolled all the features – new and old – into one offering with one price.

Finally, unbundling can be advantageous if customers pay particular attention to how much one aspect of your offering costs, but less attention to others. The rule of thumb is that you should design an offering in such a way that you are more competitive on the features that are at the customer's ‘eye level’ but can afford to charge higher prices on the features that the customer seems to care less about or devote less time to scrutinizing.

Despite this, unbundling also carries risks, especially when customers try to force their suppliers to unbundle an offering against their own interests. This ‘divide-and-conquer’ approach is a manifestation of the Digital Age, which has made transparency a fact of life. But sellers need to view buyers' pressure for transparency as a Trojan Horse. It is one thing to share information openly in the interest of serving customers and creating value for them. But it is another thing entirely for a supplier to reveal so much information that the buyers can abuse the transparency and come up with discrete, standardized offers that machines are able to process individually. Differentiation is the source of your advantages and your profits. Market standardization is the enemy of differentiation, which means that market standardization can be the enemy of profit. Don't let price become the sole difference between you and your competitors.

When the answer to ‘bundle or unbundle?’ is ‘both’

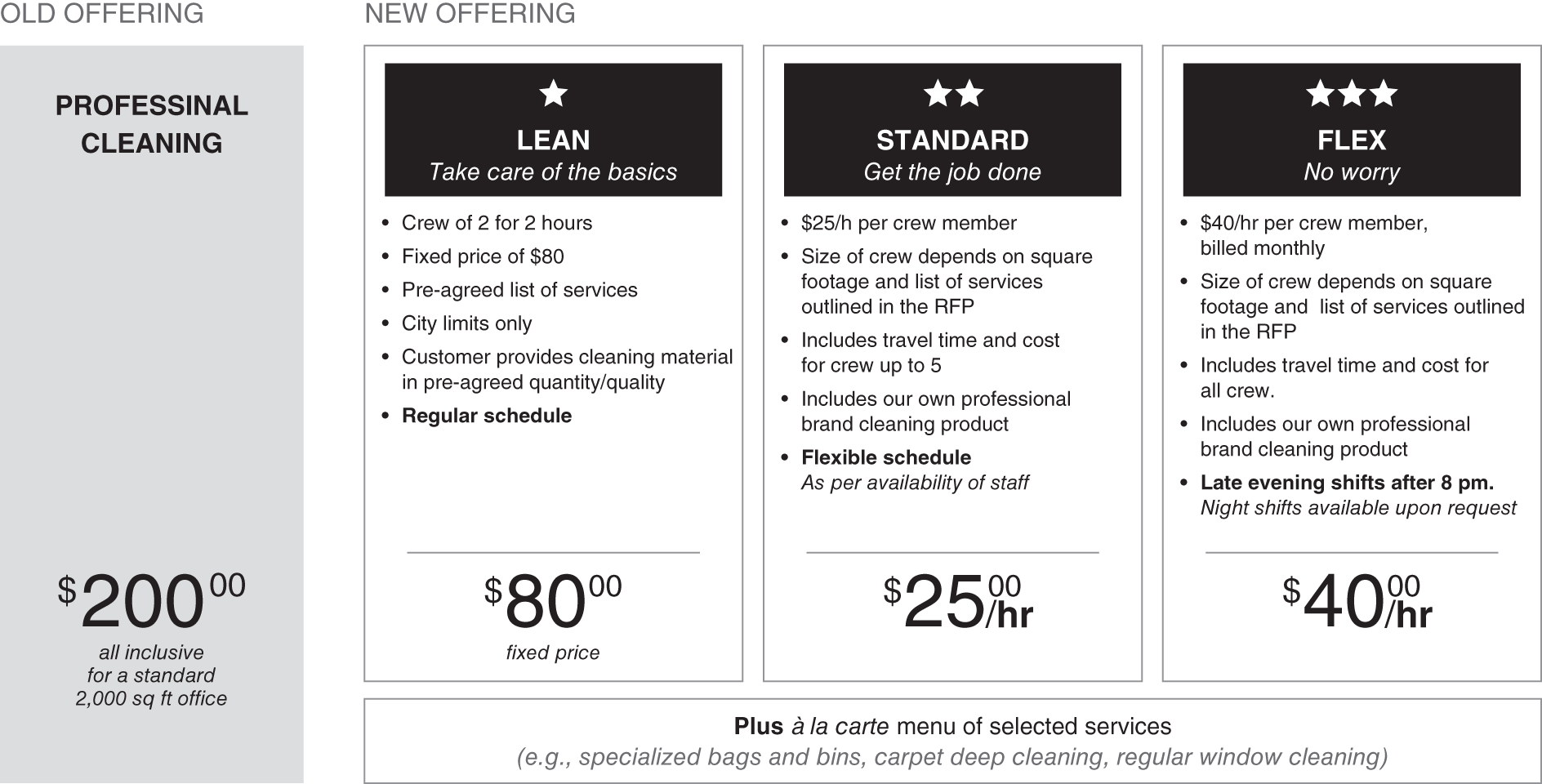

Imagine that you work for a facilities management company that specializes in professional cleaning services for large buildings. At the moment, your projects are all based on the simplest of price calculations: $200 for a standard office of 2,000 square feet, all inclusive, no matter who the customer is.

But you have noticed that the disadvantages of a one-size-fits-all price often outweigh its extreme simplicity. Some office managers can be very creative when it comes to finding reasons to ask for a lower price, either because their office space is sparsely furnished or because they feel the cleaning requirements are not very demanding. Others see the price and make long lists of demands on your cleaning crews, so that they feel like they're getting the most for their money.

The term ‘all inclusive’ gives the impression that you are offering a bundle, but in the spirit of what we described above, such an all-inclusive offering is not a bundle. It does not make the customer's buying decision easier. It makes neither your operations nor your customers' more efficient. It makes the price the only differentiator in your value proposition. It leaves you no opportunities to upsell or use other techniques to influence a buyer's decision.

At the same time, your costs alone make this all-inclusive offering a prime candidate for unbundling. Suburban locations can be difficult to reach, not only because of the distance but because of rush-hour traffic. Customer demands may require you to use specialty chemicals or equipment to complete a job professionally, and these added costs can devour your margins in a hurry.

Figure 17.2 shows a before-and-after concept for how a cleaning service could take advantage of bundling and unbundling simultaneously in order to make itself more attractive, create revenue opportunities, and make it easier for customers to choose an option that works for them without tedious negotiations that start from scratch.

Figure 17.2 A facilities management firm makes its offers more appealing and more differentiated through bundling and unbundling of its ‘all inclusive’ offer

The original motivation behind the old offering was simplicity and clarity. The company chose a nice round number for the price ($200), which seemed like a good average price for professional cleaning. The company also felt that it had established an anchor that could guide its negotiations. But the visible and invisible costs of using that simple approach were very high. First, the magic of differentiation lies in the distribution of customers, not their average. The appropriate price for a small suburban business with modest cleaning needs and the appropriate price for a high-profile downtown law firm might average out to $200, but the true costs of those jobs – and the quality expectations of the customers – could hardly be more different.

The bundles in the new approach allow customers to self-select their desired level of service by picking the offering they feel most comfortable with. The terms of each offering help ensure that costs will not explode and quality will not suffer if customers are demanding. Even if customers try to negotiate, the starting basis is much more reasonable.

Notes

- 1. Medvec, V.H., Madey, S.F., and Gilovich, T. (1995). When less is more: counterfactual thinking and satisfaction among Olympic medalists. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69 (4): 603.

- 2. Hsee, C.K. (1998). Less is better: when low-value options are valued more highly than high-value options. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 11 (2): 107–121.

- 3. Medvec, V.H., Madey, S.F., and Gilovich, T. (1995). When less is more: counterfactual thinking and satisfaction among Olympic medalists. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69 (4): 603.

- 4. Hsee, C.K. (1998). Less is better: when low-value options are valued more highly than high-value options. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 11 (2): 107–121.

- 5. This story is based on a tale from the Cold War era, when Pravda (the official newspaper of the Soviet Union) supposedly claimed that Soviet premier Nikita Khruschev finished second in a foot race, while the much younger and fitter US President John F. Kennedy came in next to last. The report conveniently omitted the fact that the two world leaders were the only ones competing in the race.

- 6. Hsee, C.K. (1998). Less is better: when low-value options are valued more highly than high-value options. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 11 (2): 107–121.

- 7. Brough, A.R. and Chernev, A. (2011). When opposites detract: categorical reasoning and subtractive valuations of product combinations. Journal of Consumer Research 39 (2): 399–414.

- 8. Brough, A.R. and Chernev, A. (2019, May 11). When two products are less than one. Kellogg Insight. https://insight.kellogg.northwestern.edu/article/when_two_products_are_less_than_one (accessed 27 May 2022).