Chapter 1. The Recipes

1.1. Downloading and Installing R

Problem

You want to install R on your computer.

Solution

Windows and OS X users can download R from CRAN, the Comprehensive R Archive Network. Linux and Unix users can install R packages using their package management tool.

- Windows

Open http://www.r-project.org/ in your browser.

Click on “CRAN”. You’ll see a list of mirror sites, organized by country.

Select a site near you.

Click on “Windows” under “Download and Install R”.

Click on “base”.

Click on the link to download the latest version of R (an .exe file).

When the download completes, double-click the .exe file and answer the usual questions.

- OS X

Open http://www.r-project.org/ in your browser.

Click on “CRAN”. You’ll see a list of mirror sites, organized by country.

Select a site near you.

Click on “MacOS X”.

Click on the .pkg file for the latest version of R, under “Files:”, to download it.

When the download completes, double-click the .pkg file and answer the usual questions.

- Linux or Unix

The major Linux distributions have packages for installing R. Here are some examples:

Distribution Package name Ubuntu or Debian r-base Red Hat or Fedora R.i386 Suse R-base Use the system’s package manager to download and install the package. Normally, you will need the root password or

sudoprivileges; otherwise, ask a system administrator to perform the installation.

Discussion

Installing R on Windows or OS X is straightforward because there are prebuilt binaries for those platforms. You need only follow the preceding instructions. The CRAN Web pages also contain links to installation-related resources, such as frequently asked questions (FAQs) and tips for special situations (“How do I install R when using Windows Vista?”) that you may find useful.

Theoretically, you can install R on Linux or Unix in one of two ways: by installing a distribution package or by building it from scratch. In practice, installing a package is the preferred route. The distribution packages greatly streamline both the initial installation and subsequent updates.

On Ubuntu or Debian, use apt-get to download and install R. Run under

sudo to have the necessary

privileges:

$ sudo apt-get install r-baseOn Red Hat or Fedora, use yum:

$ sudo yum install R.i386Most platforms also have graphical package managers, which you might find more convenient.

Beyond the base packages, I recommend installing the documentation

packages, too. On my Ubuntu machine, for example, I installed r-base-html (because I like browsing the

hyperlinked documentation) as well as r-doc-html, which installs the important R

manuals locally:

$ sudo apt-get install r-base-html r-doc-htmlSome Linux repositories also include prebuilt copies of R packages available on CRAN. I don’t use them because I’d rather get my software directly from CRAN itself, which usually has the freshest versions.

In rare cases, you may need to build R from scratch. You might have an obscure, unsupported version of Unix; or you might have special considerations regarding performance or configuration. The build procedure on Linux or Unix is quite standard. Download the tarball from the home page of your CRAN mirror; it’s called something like R-2.12.1.tar.gz, except the “2.12.1” will be replaced by the latest version. Unpack the tarball, look for a file called INSTALL, and follow the directions.

See Also

R in a Nutshell contains more details for downloading and installing R, including instructions for building the Windows and OS X versions. Perhaps the ultimate guide, though, is R Installation and Administration (http://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/R-admin.html), available on CRAN, which describes how to build and install R on a variety of platforms.

This recipe is about installing the base package. Use the install.packages function to install add-on

packages from CRAN.

1.2. Getting Help on a Function

Problem

You want to know more about a function that is installed on your machine.

Solution

Use help to display the

documentation for the function:

> help(functionname)Use args for a quick reminder

of the function arguments:

> args(functionname)Use example to see examples of

using the function:

> example(functionname)Discussion

I present many R functions in this book. Every R function has more bells and whistles than I can possibly describe. If a function catches your interest, I strongly suggest reading the help page for that function. One of its bells or whistles might be very useful to you.

Suppose you want to know more about the mean function. Use the help function like this:

> help(mean)This will either open a window with function documentation or

display the documentation on your console, depending on your platform. A

shortcut for the help command is to

simply type ?, followed by the function name:

> ?meanSometimes you just want a quick reminder of the arguments to a

function; what are they, and in what order do they occur? Use the

args function:

>args(mean)function (x, ...) NULL >args(sd)function (x, na.rm = FALSE) NULL

The first line of output from args is a synopsis of the function call. For

mean, the synopsis shows one

argument, x, which is a vector of numbers. For

sd, the synopsis shows the same

vector, x, and an optional argument called na.rm. (You can ignore the second line of

output, which is often just NULL.)

Most documentation for functions includes examples near the end. A

cool feature of R is that you can request that it execute the examples,

giving you a little demonstration of the function’s capabilities. The

documentation for the mean function,

for instance, contains examples, but you don’t need to type them

yourself. Just use the example

function to watch them run:

> example(mean)

mean> x <- c(0:10, 50)

mean> xm <- mean(x)

mean> c(xm, mean(x, trim = 0.1))

[1] 8.75 5.50

mean> mean(USArrests, trim = 0.2)

Murder Assault UrbanPop Rape

7.42 167.60 66.20 20.16The user typed example(mean).

Everything else was produced by R, which executed the examples from the

help page and displayed the results.

1.3. Viewing the Supplied Documentation

Problem

You want to read the documentation supplied with R.

Solution

Use the help.start function to

see the documentation’s table of contents:

> help.start()From there, links are available to all the installed documentation.

Discussion

The base distribution of R includes a wealth of documentation—literally thousands of pages. When you install additional packages, those packages contain documentation that is also installed on your machine.

It is easy to browse this documentation via the help.start function, which opens a window on

the top-level table of contents; see Figure 1-1.

The two links in the Reference section are especially useful:

- Packages

Click here to see a list of all the installed packages, both in the base packages and the additional installed packages. Click on a package name to see a list of its functions and datasets.

- Search Engine & Keywords

Click here to access a simple search engine, which allows you to search the documentation by keyword or phrase. There is also a list of common keywords, organized by topic; click one to see the associated pages.

See Also

The local documentation is copied from the R Project website, which may have updated documents.

1.4. Searching the Web for Help

Problem

You want to search the Web for information and answers regarding R.

Solution

Inside R, use the RSiteSearch

function to search by keyword or phrase:

> RSiteSearch("key phrase")In your browser, try using these sites for searching:

- http://rseek.org

This is a Google custom search that is focused on R-specific websites.

- http://stackoverflow.com/

Stack Overflow is a searchable Q&A site oriented toward programming issues such as data structures, coding, and graphics.

- http://stats.stackexchange.com/

The Statistical Analysis area on Stack Exchange is also a searchable Q&A site, but it is oriented more toward statistics than programming.

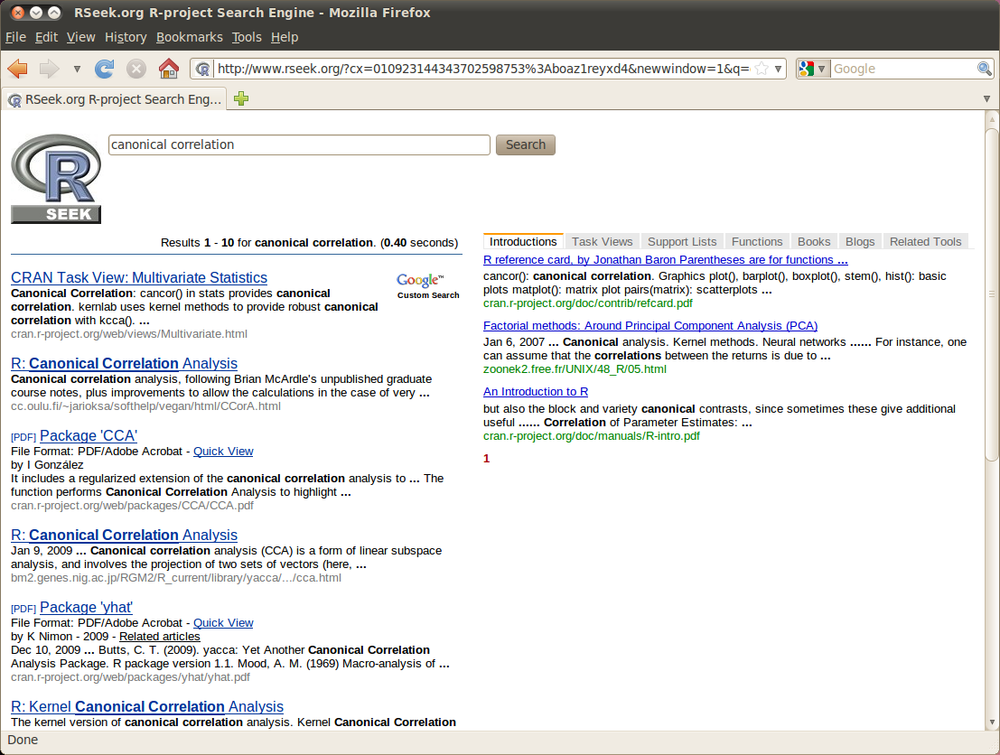

Discussion

The RSiteSearch function will

open a browser window and direct it to the search engine on the R

Project website (http://search.r-project.org/).

There, you will see an initial search that you can refine. For example,

this call would start a search for “canonical correlation”:

> RSiteSearch("canonical correlation")This is quite handy for doing quick Web searches without leaving R. However, the search scope is limited to R documentation and the mailing-list archives.

RSeek.org provides a wider search. Its virtue is that it harnesses the power of the Google search engine while focusing on sites relevant to R. That eliminates the extraneous results of a generic Google search. The beauty of RSeek.org is that it organizes the results in a useful way.

Figure 1-2 shows the results of visiting RSeek.org and searching for “canonical correlation”. The left side of the page shows general results for search R sites. The right side is a tabbed display that organizes the search results into several categories:

Introductions

Task Views

Support Lists

Functions

Books

Blogs

Related Tools

If you click on the Introductions tab, for example, you’ll find tutorial material. The Task Views tab will show any Task View that mentions your search term. Likewise, clicking on Functions will show links to relevant R functions. This is a good way to zero in on search results.

Stack Overflow is a so-called Q&A site, which means that anyone can submit a question and experienced users will supply answers—often there are multiple answers to each question. Readers vote on the answers, so good answers tend to rise to the top. This creates a rich database of searchable Q&A dialogs. Stack Overflow is strongly problem oriented, and the topics lean toward the programming side of R.

Stack Overflow hosts questions for many programming languages; therefore, when entering a term into their search box, prefix it with “[r]” to focus the search on questions tagged for R. For example, searching for “[r] standard error” will select only the questions tagged for R and will avoid Python and C++ questions.

Stack Exchange (not Overflow) has a Q&A area for Statistical Analysis. The area is more focused on statistics than programming, so use this site when seeking answers that are more concerned with statistics in general and less with R in particular.

See Also

If your search reveals a useful package, use the install.packages function to install it on

your machine.

1.5. Reading Tabular Datafiles

Problem

You want to read a text file that contains a table of data.

Solution

Use the read.table function,

which returns a data frame:

> dfrm <- read.table("filename.txt")Discussion

Tabular datafiles are quite common. They are text files with a simple format:

Each line contains one record.

Within each record, fields (items) are separated by a one-character delimiter, such as a space, tab, colon, or comma.

Each record contains the same number of fields.

This format is more free-form than the fixed-width format because

fields needn’t be aligned by position. Here is a datafile in tabular

format, called statisticians.txt,

using a space character between fields:

Fisher R.A. 1890 1962 Pearson Karl 1857 1936 Cox Gertrude 1900 1978 Yates Frank 1902 1994 Smith Kirstine 1878 1939

The read.table function is

built to read this file. By default, it assumes the data fields are

separated by white space (blanks or tabs):

>dfrm <- read.table("statisticians.txt")>print(dfrm)V1 V2 V3 V4 1 Fisher R.A. 1890 1962 2 Pearson Karl 1857 1936 3 Cox Gertrude 1900 1978 4 Yates Frank 1902 1994 5 Smith Kirstine 1878 1939

If your file uses a separator other than white space, specify it

using the sep parameter. For example,

if our file used a colon (:) as the

field separator, we would read it this way:

> dfrm <- read.table("statisticians.txt", sep=":")You can’t tell from the printed output, but read.table interpreted the first and last

names as factors, not strings. We see that by checking the class of the

resulting column:

> class(dfrm$V1)

[1] "factor"To prevent read.table from

interpreting character strings as factors, set the stringsAsFactors parameter to FALSE:

>dfrm <- read.table("statisticians.txt", stringsAsFactor=FALSE)>class(dfrm$V1)[1] "character"

Now the class of the first column is character, not factor.

If any field contains the string “NA”, then read.table assumes that the value is missing

and converts it to NA. Your datafile might employ a different string to

signal missing values; if it does, use the na.strings parameter. The SAS convention, for

example, is that missing values are signaled by a single period

(.). We can read such datafiles like

this:

> dfrm <- read.table("filename.txt", na.strings=".")I am a huge fan of self-describing data:

datafiles which describe their own contents. (A computer scientist would

say the file contains its own metadata.) The

read.table function has two features

that support this characteristic. First, you can include a

header line at the top of your file that gives

names to the columns. The line contains one name for every column, and

it uses the same field separator as the data. Here is our datafile with

a header line that names the columns:

lastname firstname born died Fisher R.A. 1890 1962 Pearson Karl 1857 1936 Cox Gertrude 1900 1978 Yates Frank 1902 1994 Smith Kirstine 1878 1939

Now we can tell read.table that

our file contains a header line, and it will use the column names when

it builds the data frame:

>dfrm <- read.table("statisticians.txt", header=TRUE, stringsAsFactor=FALSE)>print(dfrm)lastname firstname born died 1 Fisher R.A. 1890 1962 2 Pearson Karl 1857 1936 3 Cox Gertrude 1900 1978 4 Yates Frank 1902 1994 5 Smith Kirstine 1878 1939

The second feature of read.table is comment

lines. Any line that begins with a pound sign (#) is ignored, so you can put comments on

those lines:

# This is a datafile of famous statisticians. # Last edited on 1994-06-18 lastname firstname born died Fisher R.A. 1890 1962 Pearson Karl 1857 1936 Cox Gertrude 1900 1978 Yates Frank 1902 1994 Smith Kirstine 1878 1939

read.table has many parameters

for controlling how it reads and interprets the input file. See the help

page for details.

See Also

If your data items are separated by commas, see Recipe 1.6 for reading a CSV file.

1.6. Reading from CSV Files

Problem

You want to read data from a comma-separated values (CSV) file.

Solution

The read.csv function can read

CSV files. If your CSV file has a header line, use this:

> tbl <- read.csv("filename")If your CSV file does not contain a header line, set the header option to FALSE:

> tbl <- read.csv("filename", header=FALSE)Discussion

The CSV file format is popular because many programs can import and export data in that format. Such programs include R, Excel, other spreadsheet programs, many database managers, and most statistical packages. CSV is a flat file of tabular data, in which each line in the file is a row of data, and each row contains data items separated by commas. Here is a very simple CSV file with three rows and three columns (the first line is a header line that contains the column names, also separated by commas):

label,lbound,ubound low,0,0.674 mid,0.674,1.64 high,1.64,2.33

The read.csv function reads the

data and creates a data frame, which is the usual R representation for

tabular data. The function assumes that your file has a header line

unless told otherwise:

>tbl <- read.csv("table-data.csv")>tbllabel lbound ubound 1 low 0.000 0.674 2 mid 0.674 1.640 3 high 1.640 2.330

Observe that read.csv took the

column names from the header line for the data frame. If the file did

not contain a header, we would specify header=FALSE, and R would synthesize column

names for us (V1, V2, and V3

in this case):

>tbl <- read.csv("table-data-with-no-header.csv", header=FALSE)>tblV1 V2 V3 1 low 0.000 0.674 2 mid 0.674 1.640 3 high 1.640 2.330

A good feature of read.csv is

that is automatically interprets nonnumeric data as a factor

(categorical variable), which is often what you want since this is,

after all, a statistical package, not Perl. The label

variable in the tbl data frame just shown is actually

a factor, not a character variable. You see that by inspecting the

structure of tbl:

> str(tbl)

'data.frame': 3 obs. of 3 variables:

$ label : Factor w/ 3 levels "high","low","mid": 2 3 1

$ lbound: num 0 0.674 1.64

$ ubound: num 0.674 1.64 2.33Sometimes, you really want your data interpreted as strings, not

as factors. In that case, set the as.is parameter to TRUE; this indicates that R should not

interpret nonnumeric data as a factor:

>tbl <- read.csv("table-data.csv", as.is=TRUE)>str(tbl)'data.frame': 3 obs. of 3 variables: $ label : chr "low" "mid" "high" $ lbound: num 0 0.674 1.64 $ ubound: num 0.674 1.64 2.33

Notice that the label variable

now has character-string values and is no longer a factor.

Another useful feature is that input lines starting with a pound

sign (#) are ignored, which lets you

embed comments in your datafile. Disable this feature by specifying

comment.char="".

The read.csv function has many

useful bells and whistles. These include the ability to skip leading

lines in the input file, control the conversion of individual columns,

fill out short rows, limit the number of lines, and control the quoting

of strings. See the R help page for details.

See Also

See the R help page for read.table, which is the basis for read.csv. See the write.csv function for writing CSV

files.

1.7. Creating a Vector

Problem

You want to create a vector.

Solution

Use the c(...) operator to

construct a vector from given values.

Discussion

Vectors are a central component of R, not just another data structure. A vector can contain numbers, strings, or logical values, but not a mixture.

The c(...) operator can

construct a vector from simple elements:

>c(1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21)[1] 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 >c(1*pi, 2*pi, 3*pi, 4*pi)[1] 3.141593 6.283185 9.424778 12.566371 >c("Everyone", "loves", "stats.")[1] "Everyone" "loves" "stats." >c(TRUE,TRUE,FALSE,TRUE)[1] TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE

If the arguments to c(...) are

themselves vectors, it flattens them and combines them into a single

vector:

>v1 <- c(1,2,3)>v2 <- c(4,5,6)>c(v1,v2)[1] 1 2 3 4 5 6

Vectors cannot contain a mix of data types, such as numbers and strings. If you create a vector from mixed elements, R will try to accommodate you by converting one of them:

>v1 <- c(1,2,3)>v3 <- c("A","B","C")>c(v1,v3)[1] "1" "2" "3" "A" "B" "C"

Here, the user tried to create a vector from both numbers and strings. R converted all the numbers to strings before creating the vector, thereby making the data elements compatible.

Technically speaking, two data elements can coexist in a vector

only if they have the same mode. The modes of

3.1415 and "foo" are numeric and character,

respectively:

>mode(3.1415)[1] "numeric" >mode("foo")[1] "character"

Those modes are incompatible. To make a vector from them, R

converts 3.1415 to character mode so it will be compatible with "foo":

>c(3.1415, "foo")[1] "3.1415" "foo" >mode(c(3.1415, "foo"))[1] "character"

Warning

c is a generic operator,

which means that it works with many datatypes and not just vectors.

However, it might not do exactly what you expect, so check its

behavior before applying it to other datatypes and objects.

1.8. Computing Basic Statistics

Problem

You want to calculate basic statistics: mean, median, standard deviation, variance, correlation, or covariance.

Solution

Use one of these functions as appropriate, assuming that x and y are

vectors:

mean(x)median(x)sd(x)var(x)cor(x, y)cov(x, y)

Discussion

When I first opened the documentation for R, I began searching for material called something like “Procedures for Calculating Standard Deviation.” I figured that such an important topic would likely require a whole chapter.

It’s not that complicated.

Standard deviation and other basic statistics are calculated by simple functions. Ordinarily, the function argument is a vector of numbers, and the function returns the calculated statistic:

>x <- c(0,1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21,34)>mean(x)[1] 8.8 >median(x)[1] 4 >sd(x)[1] 11.03328 >var(x)[1] 121.7333

The sd function calculates the

sample standard deviation, and var

calculates the sample variance.

The cor and cov functions can calculate the correlation

and covariance, respectively, between two vectors:

>x <- c(0,1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21,34)>y <- log(x+1)>cor(x,y)[1] 0.9068053 >cov(x,y)[1] 11.49988

All these functions are picky about values that are not available (NA). Even one NA value in the vector argument causes any of these functions to return NA, or even halt altogether with a cryptic error:

>x <- c(0,1,1,2,3,NA)>mean(x)[1] NA >sd(x)[1] NA

It’s annoying when R is that cautious, but it is the right thing

to do. You must think carefully about your situation. Does an NA in your

data invalidate the statistic? If yes, then R is doing the right thing.

If not, you can override this behavior by setting na.rm=TRUE, which tells R to ignore the NA

values:

>x <- c(0,1,1,2,3,NA)>mean(x, na.rm=TRUE)[1] 1.4 >sd(x, na.rm=TRUE)[1] 1.140175

A beautiful aspect of mean and

sd is that they are smart about data

frames. They understand that each column of the data frame is a

different variable, so they calculate their statistic for each column

individually. This example calculates those basic statistics for a data

frame with three columns:

>print(dframe)small medium big 1 0.6739635 10.526448 99.83624 2 1.5524619 9.205156 100.70852 3 0.3250562 11.427756 99.73202 4 1.2143595 8.533180 98.53608 5 1.3107692 9.763317 100.74444 6 2.1739663 9.806662 98.58961 7 1.6187899 9.150245 100.46707 8 0.8872657 10.058465 99.88068 9 1.9170283 9.182330 100.46724 10 0.7767406 7.949692 100.49814 >mean(dframe)small medium big 1.245040 9.560325 99.946003 >sd(dframe)small medium big 0.5844025 0.9920281 0.8135498

Notice that mean and sd both return three values, one for each

column defined by the data frame. (Technically, they return a

three-element vector in which the names attribute is taken from the columns of

the data frame.)

The var function understands

data frames, too, but it behaves quite differently from mean and sd. It calculates the covariance between the

columns of the data frame and returns the covariance matrix:

> var(dframe)

small medium big

small 0.34152627 -0.21516416 -0.04005275

medium -0.21516416 0.98411974 -0.09253855

big -0.04005275 -0.09253855 0.66186326Likewise, if x is either a data

frame or a matrix, cor(x) returns the

correlation matrix and cov(x) returns

the covariance matrix:

>cor(dframe)small medium big small 1.00000000 -0.3711367 -0.08424345 medium -0.37113670 1.0000000 -0.11466070 big -0.08424345 -0.1146607 1.00000000 >cov(dframe)small medium big small 0.34152627 -0.21516416 -0.04005275 medium -0.21516416 0.98411974 -0.09253855 big -0.04005275 -0.09253855 0.66186326

Alas, the median function does

not understand data frames. To calculate the medians of data frame

columns, use the lapply function to

apply the median function to each

column separately.

See Also

See Recipe 1.12 for calculating the confidence interval of the mean. See Recipe 1.15 for testing the significance of a correlation.

1.9. Initializing a Data Frame from Column Data

Problem

Your data is organized by columns, and you want to assemble it into a data frame.

Solution

If your data is captured in several vectors and/or factors, use

the data.frame function to assemble

them into a data frame:

> dfrm <- data.frame(v1, v2, v3, f1, f2)Use as.data.frame instead if

your data is captured in a list that contains

vectors and/or factors:

> dfrm <- as.data.frame(list.of.vectors)Discussion

A data frame is a collection of columns, each of which corresponds to an observed variable (in the statistical sense, not the programming sense). If your data is already organized into columns, then it’s easy to build a data frame.

The data.frame function can

construct a data frame from vectors, where each vector is one observed

variable. Suppose you have two numeric predictor variables, one

categorical predictor variable, and one response variable. The data.frame function can create a data frame

from your vectors:

>dfrm <- data.frame(pred1, pred2, pred3, resp)>dfrmpred1 pred2 pred3 resp 1 -2.7528917 -1.40784130 AM 12.57715 2 -0.3626909 0.31286963 AM 21.02418 3 -1.0416039 -0.69685664 PM 18.94694 4 1.2666820 -1.27511434 PM 18.98153 5 0.7806372 -0.27292745 AM 19.59455 6 -1.0832624 0.73383339 AM 20.71605 7 -2.0883305 0.96816822 PM 22.70062 8 -0.7063653 -0.84476203 PM 18.40691 9 -0.8394022 0.31530793 PM 21.00930 10 -0.4966884 -0.08030948 AM 19.31253

Notice that data.frame takes

the column names from your program variables. You can override that

default by supplying explicit column names:

>dfrm <- data.frame(p1=pred1, p2=pred2, p3=pred3, r=resp)>dfrmp1 p2 p3 r 1 -2.7528917 -1.40784130 AM 12.57715 2 -0.3626909 0.31286963 AM 21.02418 3 -1.0416039 -0.69685664 PM 18.94694 . . (etc.) .

Alternatively, your data may be organized into vectors, but those vectors are held in a list instead of individual program variables, like this:

> lst <- list(p1=pred1, p2=pred2, p3=pred3, r=resp)No problem. Use the as.data.frame function to create a data frame

from the list of vectors:

> as.data.frame(lst)

p1 p2 p3 r

1 -2.7528917 -1.40784130 AM 12.57715

2 -0.3626909 0.31286963 AM 21.02418

3 -1.0416039 -0.69685664 PM 18.94694

.

. (etc.)

.1.10. Selecting Data Frame Columns by Position

Problem

You want to select columns from a data frame according to their position.

Solution

To select a single column, use this list operator:

dfrm[[n]]Returns one column—specifically, the

nth column ofdfrm.

To select one or more columns and package them in a data frame, use the following sublist expressions:

dfrm[n]Returns a data frame consisting solely of the

nth column ofdfrm.dfrm[c(n1,n2, ...,nk)]Returns a data frame built from the columns in positions n1, n2, ..., nk of

dfrm.

You can use matrix-style subscripting to select one or more columns:

dfrm[,n]Returns the

nth column (assuming that n contains exactly one value).dfrm[,c(n1,n2, ...,nk)]Returns a data frame built from the columns in positions n1, n2, ..., nk.

Note that the matrix-style subscripting can return two different data types (either column or data frame) depending on whether you select one column or multiple columns.

Discussion

There are a bewildering number of ways to select columns from a data frame. The choices can be confusing until you understand the logic behind the alternatives. As you read this explanation, notice how a slight change in syntax—a comma here, a double-bracket there — changes the meaning of the expression.

Let’s play with the population data for the 16 largest cities in the Chicago metropolitan area:

> suburbs

city county state pop

1 Chicago Cook IL 2853114

2 Kenosha Kenosha WI 90352

3 Aurora Kane IL 171782

4 Elgin Kane IL 94487

5 Gary Lake(IN) IN 102746

6 Joliet Kendall IL 106221

7 Naperville DuPage IL 147779

8 Arlington Heights Cook IL 76031

9 Bolingbrook Will IL 70834

10 Cicero Cook IL 72616

11 Evanston Cook IL 74239

12 Hammond Lake(IN) IN 83048

13 Palatine Cook IL 67232

14 Schaumburg Cook IL 75386

15 Skokie Cook IL 63348

16 Waukegan Lake(IL) IL 91452Use simple list notation to select exactly one column, such as the first column:

> suburbs[[1]]

[1] "Chicago" "Kenosha" "Aurora" "Elgin"

[5] "Gary" "Joliet" "Naperville" "Arlington Heights"

[9] "Bolingbrook" "Cicero" "Evanston" "Hammond"

[13] "Palatine" "Schaumburg" "Skokie" "Waukegan"The first column of suburbs is a vector, so that’s what suburbs[[1]] returns: a vector. If the first

column were a factor, we’d get a factor.

The result differs when you use the single-bracket notation, as in

suburbs[1] or suburbs[c(1,3)]. You still get the

requested columns, but R wraps them in a data frame. This example

returns the first column wrapped in a data frame:

> suburbs[1]

city

1 Chicago

2 Kenosha

3 Aurora

4 Elgin

5 Gary

6 Joliet

7 Naperville

8 Arlington Heights

9 Bolingbrook

10 Cicero

11 Evanston

12 Hammond

13 Palatine

14 Schaumburg

15 Skokie

16 WaukeganThe next example returns the first and third columns wrapped in a data frame:

> suburbs[c(1,3)]

city pop

1 Chicago 2853114

2 Kenosha 90352

3 Aurora 171782

4 Elgin 94487

5 Gary 102746

6 Joliet 106221

7 Naperville 147779

8 Arlington Heights 76031

9 Bolingbrook 70834

10 Cicero 72616

11 Evanston 74239

12 Hammond 83048

13 Palatine 67232

14 Schaumburg 75386

15 Skokie 63348

16 Waukegan 91452A major source of confusion is that suburbs[[1]] and suburbs[1] look similar but produce very

different results:

suburbs[[1]]This returns one column.

suburbs[1]This returns a data frame, and the data frame contains exactly one column. This is a special case of

dfrm[c(. We don’t need then1,n2, ...,nk)]c(...)construct because there is only onen.

The point here is that “one column” is different from “a data frame that contains one column.” The first expression returns a column, so it’s a vector or a factor. The second expression returns a data frame, which is different.

R lets you use matrix notation to select columns, as shown in the Solution. But an odd quirk can bite you: you might get a column or you might get a data frame, depending which many subscripts you use. In the simple case of one index you get a column, like this:

> suburbs[,1]

[1] "Chicago" "Kenosha" "Aurora" "Elgin"

[5] "Gary" "Joliet" "Naperville" "Arlington Heights"

[9] "Bolingbrook" "Cicero" "Evanston" "Hammond"

[13] "Palatine" "Schaumburg" "Skokie" "Waukegan"But using the same matrix-style syntax with multiple indexes returns a data frame:

> suburbs[,c(1,4)]

city pop

1 Chicago 2853114

2 Kenosha 90352

3 Aurora 171782

4 Elgin 94487

5 Gary 102746

6 Joliet 106221

7 Naperville 147779

8 Arlington Heights 76031

9 Bolingbrook 70834

10 Cicero 72616

11 Evanston 74239

12 Hammond 83048

13 Palatine 67232

14 Schaumburg 75386

15 Skokie 63348

16 Waukegan 91452This creates a problem. Suppose you see this expression in some old R script:

dfrm[,vec]

Does that return a column or a data frame? Well, it depends. If

vec contains one value, you get a

column; otherwise, you get a data frame. You cannot tell from the syntax

alone.

To avoid this problem, you can include drop=FALSE in the subscripts; this forces R to

return a data frame:

dfrm[,vec,drop=FALSE]

Now there is no ambiguity about the returned data structure. It’s a data frame.

When all is said and done, using matrix notation to select columns from data frames is not the best procedure. I recommend that you instead use the list operators described previously. They just seem clearer.

1.11. Selecting Data Frame Columns by Name

Problem

You want to select columns from a data frame according to their name.

Solution

To select a single column, use one of these list expressions:

dfrm[["name"]]Returns one column, the column called

name.dfrm$nameReturns the same, but presented in different syntax.

To select one or more columns and package them in a data frame, use these list expressions:

dfrm["name"]Selects one column and packages it inside a data frame object.

dfrm[c("name1", "name2", ..., "namek")]Selects several columns and packages them in a data frame.

You can use matrix-style subscripting to select one or more columns:

dfrm[, "name"]Returns the named column.

dfrm[,c("name1", "name2", ..., "namek")]Selects several columns and packages them in a data frame.

Once again, the matrix-style subscripting can return two different data types (column or data frame) depending on whether you select one column or multiple columns.

Discussion

All columns in a data frame must have names. If you know the name, it’s usually more convenient and readable to select by name, rather than by position.

The solutions just described are similar to those for Recipe 1.10, where we selected columns by position. The only difference is that here we use column names instead of column numbers. All the observations made in Recipe 1.10 apply here:

dfrm[["name"]]returns one column, not a data frame.dfrm[c("returns a data frame, not a column.name1", "name2", ..., "namek")]dfrm["name"]is a special case of the previous expression and so returns a data frame, not a column.The matrix-style subscripting can return either a column or a data frame, so be careful how many names you supply. See Recipe 1.10 for a discussion of this “gotcha” and using

drop=FALSE.

There is one new addition:

dfrm$name

This is identical in effect to dfrm[["name"]], but it’s easier to type and to

read.

See Also

See Recipe 1.10 to understand more about selecting columns.

1.12. Forming a Confidence Interval for a Mean

Problem

You have a sample from a population. Given that sample, you want to determine a confidence interval for the population’s mean.

Solution

Apply the t.test function to

your sample x:

> t.test(x)The output includes a confidence interval at the 95% confidence

level. To see intervals at other levels, use the conf.level argument.

If your sample size n is small, the underlying population must be normally distributed for there to be a meaningful confidence interval. A good rule of thumb is that “small” means n < 30.

Discussion

Applying the t.test function to

a vector yields a lot of output. Buried in the output is a confidence

interval:

>x <- rnorm(50, mean=100, sd=15)>t.test(x)One Sample t-test data: x t = 59.2578, df = 49, p-value < 2.2e-16 alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 0 95 percent confidence interval: 97.16167 103.98297 sample estimates: mean of x 100.5723

In this example, the confidence interval is approximately 97.16 < μ < 103.98, which is sometimes written simply as (97.16, 103.98).

We can raise the confidence level to 99% by setting conf.level=0.99:

> t.test(x, conf.level=0.99)

One Sample t-test

data: x

t = 59.2578, df = 49, p-value < 2.2e-16

alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 0

99 percent confidence interval:

96.0239 105.1207

sample estimates:

mean of x

100.5723 That change widens the confidence interval to 96.02 < μ < 105.12.

1.13. Forming a Confidence Interval for a Proportion

Problem

You have a sample of values from a population consisting of successes and failures. Based on the sample data, you want to form a confidence interval for the population’s proportion of successes.

Solution

Use the prop.test function.

Suppose the sample size is n and the sample

contains x successes:

> prop.test(n, x)The function output includes the confidence interval for p.

Discussion

I subscribe to a stock market newsletter that is well written for the most part, but includes a section purporting to identify stocks that are likely to rise. It does this by looking for a certain pattern in the stock price. It recently reported, for example, that a certain stock was following the pattern. It also reported that the stock rose six times after the last nine times that pattern occurred. The writers concluded that the probability of the stock rising again was therefore 6/9 or 66.7%.

Using prop.test, we can obtain

the confidence interval for the true proportion of times the stock rises

after the pattern. Here, the number of observations is

n = 9 and the number of successes is

x = 6. The output shows a confidence interval of

(0.309, 0.910) at the 95% confidence level:

> prop.test(6, 9)

1-sample proportions test with continuity correction

data: 6 out of 9, null probability 0.5

X-squared = 0.4444, df = 1, p-value = 0.505

alternative hypothesis: true p is not equal to 0.5

95 percent confidence interval:

0.3091761 0.9095817

sample estimates:

p

0.6666667The writers are pretty foolish to say the probability of rising is 66.7%. They could be leading their readers into a very bad bet.

By default, prop.test

calculates a confidence interval at the 95% confidence level. Use the

conf.level argument for other

confidence levels, like this:

> prop.test(n, x, p, conf.level=0.99) # 99% confidence level1.14. Comparing the Means of Two Samples

Problem

You have one sample each from two populations. You want to know if the two populations could have the same mean.

Solution

Perform a t test by calling the t.test function:

> t.test(x, y)By default, t.test assumes that

your data is not paired. If the observations are paired (i.e., if each

xi is paired with the

corresponding yi), then

specify paired=TRUE:

> t.test(x, y, paired=TRUE)In either case, t.test will

compute a p-value. Conventionally, if

p < 0.05, the means are likely different,

whereas p > 0.05 provides no such

evidence:

If either sample size is small, the populations must be normally distributed. Here, “small” means fewer than 20 data points.

If the two populations have the same variance, specify

var.equal=TRUEto obtain a less conservative test.

Discussion

I often use the t test to get a quick sense of the difference between two population means. It requires that the samples be large enough—both samples have 20 or more observations—or that the underlying populations be normally distributed. I don’t take the “normally distributed” part too literally. Being bell-shaped should be good enough.

A key distinction here is whether your data contains paired observations, since the answer may cause your results to differ. Suppose we want to know if coffee in the morning improves scores on SAT tests. We could run the experiment two ways:

Randomly select one group of people. Give them the SAT test twice, once with morning coffee and once without morning coffee. For each person, we will have two SAT scores. These are paired observations.

Randomly select two groups of people. One group has a cup of morning coffee and takes the SAT test. The other group just takes the test. We have a score for each person, but the scores are not paired in any way.

Statistically, these experiments are quite different. In experiment 1, there are two observations for each person (caffeinated and decaf) and they are not statistically independent. In experiment 2, the data is independent.

If you have paired observations (experiment 1) and erroneously analyze them as unpaired observations (experiment 2), then you could get this result with a p-value of 0.9867:

> t.test(x,y)

Welch Two Sample t-test

data: x and y

t = -0.0166, df = 198, p-value = 0.9867

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-30.56737 30.05605

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

501.2008 501.4565The large p-value forces you to conclude that there is no difference between the groups. Contrast that result with the one from analyzing the same data, but correctly identifying it as paired:

> t.test(x, y, paired=TRUE)

Paired t-test

data: x and y

t = -2.3636, df = 99, p-value = 0.02005

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-0.4702824 -0.0410375

sample estimates:

mean of the differences

-0.2556599The p-value plummets to 0.02005, and we reach exactly the opposite conclusion.

See Also

If the populations are not normally distributed (bell-shaped) and

either sample is small, the t test is

inappropriate. In that case, consider using the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, which is implemented by the

wilcox.test function.

1.15. Testing a Correlation for Significance

Problem

You calculated the correlation between two variables, but you don’t know if the correlation is statistically significant.

Solution

The cor.test function can

calculate both the p-value and the confidence

interval of the correlation. If the variables came from normally

distributed populations, use the default measure of correlation, known

as the Pearson method:

> cor.test(x, y)For nonnormal populations, use the Spearman method instead:

> cor.test(x, y, method="Spearman")The function returns several values, including the p-value from the test of significance. Conventionally, p < 0.05 indicates that the correlation is likely significant, whereas p > 0.05 indicates it is not.

Discussion

In my experience, people often fail to check a correlation for

significance. In fact, many people are unaware that a correlation can be

insignificant. They jam their data into a computer, calculate the

correlation, and blindly believe the result. However, they should ask

themselves: Was there enough data? Is the magnitude of the correlation

large enough? Fortunately, the cor.test function answers those

questions.

Suppose we have two vectors, x and y, with values from normal populations. We might be very pleased that their correlation is greater than 0.83:

> cor(x, y)

[1] 0.8352458But that is naïve. If we run cor.test, it reports a relatively large

p-value of 0.1648:

> cor.test(x, y)

Pearson's product-moment correlation

data: x and y

t = 2.1481, df = 2, p-value = 0.1648

alternative hypothesis: true correlation is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-0.6379590 0.9964437

sample estimates:

cor

0.8352458The p-value is above the conventional threshold of 0.05, so we conclude that the correlation is unlikely to be significant.

You can also check the correlation by using the confidence interval. In this example, the confidence interval is (−0.638, 0.996). The interval contains zero, so it is possible that the correlation is zero, in which case there would be no correlation. Again, you could not be confident that the reported correlation is significant.

The cor.test output also

includes the point estimate reported by cor (at the bottom, labeled “sample

estimates”), saving you the additional step of running cor.

By default, cor.test calculates

the Pearson correlation, which assumes that the underlying populations

are normally distributed. The Spearman method makes no such assumption

because it is nonparametric. Use method="Spearman" when working with nonnormal

data.

See Also

See Recipe 1.8 for computing correlations and other basic statistics.

1.16. Creating a Scatter Plot

Problem

You have paired observations: (x1, y1), (x2, y2), ..., (xn, yn). You want to create a scatter plot of the pairs.

Solution

If your data is held in two parallel vectors,

x and y, use them as arguments

of plot:

> plot(x, y)If your data is held in a (two-column) data frame, plot the data frame:

> plot(dfrm)Discussion

A scatter plot is usually my first attack on a new dataset. It’s a quick way to see the relationship, if any, between x and y. Creating the scatter plot is easy:

> plot(x, y)The plot function does not

return anything. Rather, its purpose is to draw a plot of the

(x, y) pairs in the graphics window.

Life is even easier if your data is captured in a two-column data

frame. If you plot a two-column data

frame, the function assumes you want a scatter plot created from those

two columns. The scatter plot shown in Figure 1-3 was created by one call to

plot:

> plot(cars)The cars dataset contains two

columns: speed and dist. The first column is speed, so that becomes the

x-axis, and dist

becomes the y-axis.

If your data frame contains more than two columns, you will get multiple scatter plots, which might or might not be useful.

To get a scatter plot, your data must be numeric. Recall that

plot is a polymorphic function, so,

if the arguments are nonnumeric, it will create some other type of plot.

See Recipe 1.18, for example, which creates box

plots from factors.

See Also

See the help page for plot to

learn more about adding a title, subtitle, and labels.

1.17. Creating a Bar Chart

Problem

You want to create a bar chart.

Solution

Use the barplot function. The

first argument is a vector of bar heights:

> barplot(c(height1, height2, height3))Discussion

The barplot function produces a

simple bar chart. It assumes that the heights of your bars are

conveniently stored in a vector. That is not always the case, however.

Often, you have a vector of numeric data and a parallel factor that

groups the data, and you want to produce a bar chart of the group means

or the group totals. For example, the airquality dataset contains a numeric Temp column and a Month column. We can create a bar chart of the

mean temperature by month in two steps. First, we compute the

means:

> heights <- tapply(airquality$Temp, airquality$Month, mean)That gives the heights of the bars, from which we create the bar chart:

> barplot(heights)The result is shown in the lefthand panel of Figure 1-4. The result is pretty bland, as you can see, so it’s common to add some simple adornments: a title, labels for the bars, and a label for the y-axis:

>barplot(heights,+main="Mean Temp. by Month",+names.arg=c("May", "Jun", "Jul", "Aug", "Sep"),+ylab="Temp (deg. F)")

The righthand panel of Figure 1-4 shows the improved bar chart.

See Also

The barchart function in the

lattice package is another way to

produce a bar chart.

1.18. Creating a Box Plot

Problem

You want to create a box plot of your data.

Solution

Use boxplot(, where

x)x is a vector of numeric values.

Discussion

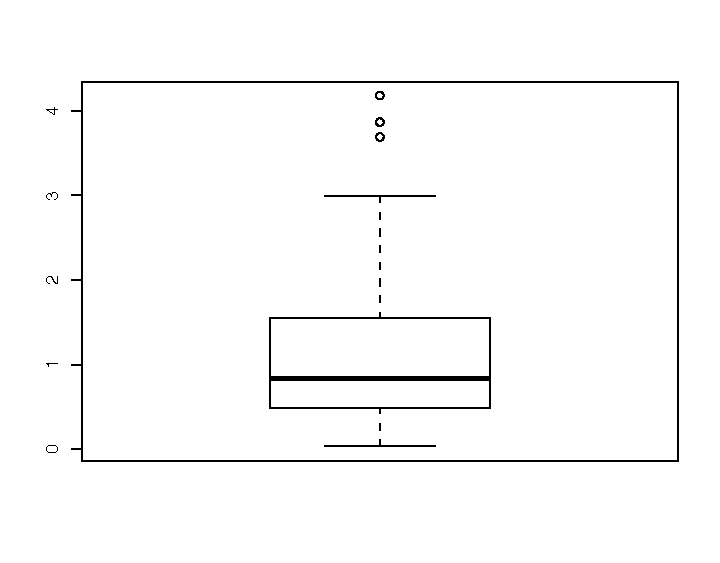

A box plot provides a quick and easy visual summary of a dataset. Figure 1-5 shows a typical box plot:

The thick line in the middle is the median.

The box surrounding the median identifies the first and third quartiles; the bottom of the box is Q1, and the top is Q3.

The “whiskers” above and below the box show the range of the data, excluding outliers.

The circles identify outliers. By default, an outlier is defined as any value that is farther than 1.5 × IQR away from the box. (IQR is the interquartile range, or Q3 − Q1.) In this example, there are three outliers.

1.19. Creating a Histogram

Problem

You want to create a histogram of your data.

Solution

Use hist(, where

x)x is a vector of numeric values.

Discussion

The lefthand panel of Figure 1-6

shows a histogram of the MPG.city

column taken from the Cars93 dataset,

created like this:

>data(Cars93, package="MASS")>hist(Cars93$MPG.city)

The hist function must decide

how many cells (bins) to create for binning the data. In this example,

the default algorithm chose seven bins. That creates too few bars for my

taste, because the shape of the distribution remains hidden. So, I would

include a second argument for hist—namely, the suggested number of

bins:

> hist(Cars93$MPG.city, 20)The number is only a suggestion, but hist will expand the number of bins as

possible to accommodate that suggestion.

The righthand panel of Figure 1-6 shows a histogram for the same data, but with more bins and with replacements for the default title and x-axis label. It was created like this:

> hist(Cars93$MPG.city, 20, main="City MPG (1993)", xlab="MPG")See Also

The histogram function of the

lattice package is an alternative to

hist.

1.20. Performing Simple Linear Regression

Problem

You have two vectors, x and y, that hold paired observations: (x1, y1), (x2, y2), ..., (xn, yn). You believe there is a linear relationship between x and y, and you want to create a regression model of the relationship.

Solution

The lm function performs a

linear regression and reports the coefficients:

> lm(y ~ x)

Call:

lm(formula = y ~ x)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) x

17.72 3.25Discussion

Simple linear regression involves two variables: a predictor variable, often called x; and a response variable, often called y. The regression uses the ordinary least-squares (OLS) algorithm to fit the linear model:

yi = β0 + β1xi + εi

where β0 and β1 are the regression coefficients and εi represents the error terms.

The lm function can perform

linear regression. The main argument is a model

formula, such as y ~ x.

The formula has the response variable on the left of the tilde character

(~) and the predictor variable on the

right. The function estimates the regression coefficients,

β0 and

β1, and reports them as the

intercept and the coefficient of x, respectively:

Coefficients:

(Intercept) x

17.72 3.25In this case, the regression equation is:

yi = 17.72 + 3.25xi + εi

It is quite common for data to be captured inside a data frame, in

which case you want to perform a regression between two data frame

columns. Here, x and y are columns of a data frame dfrm:

> dfrm

x y

1 0.04781401 5.406651

2 1.90857986 19.941568

3 2.79987246 23.922613

4 4.46755305 32.432904

5 3.76490363 44.259268

6 5.92364632 61.151480

7 8.04611587 26.305505

8 7.11097986 43.606087

9 9.73645966 58.262112

10 9.19324543 57.631029

.

. (etc.)

.The lm function lets you

specify a data frame by using the data parameter. If you do, the function will

take the variables from the data frame and not from your

workspace:

> lm(y ~ x, data=dfrm) # Take x and y from dfrm

Call:

lm(formula = y ~ x, data = dfrm)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) x

17.72 3.251.21. Performing Multiple Linear Regression

Problem

You have several predictor variables (e.g., u, v, and w) and a response variable (y). You believe there is a linear relationship between the predictors and the response, and you want to perform a linear regression on the data.

Solution

Use the lm function. Specify

the multiple predictors on the righthand side of the formula, separated

by plus signs (+):

> lm(y ~ u + v + w)Discussion

Multiple linear regression is the obvious generalization of simple linear regression. It allows multiple predictor variables instead of one predictor variable and still uses OLS to compute the coefficients of a linear equation. The three-variable regression just shown corresponds to this linear model:

yi = β0 + β1ui + β2vi + β3wi + εi

R uses the lm function for both

simple and multiple linear regression. You simply add more variables to

the righthand side of the model formula. The output then shows the

coefficients of the fitted model:

> lm(y ~ u + v + w)

Call:

lm(formula = y ~ u + v + w)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) u v w

1.4222 1.0359 0.9217 0.7261The data parameter of lm is especially valuable when the number of

variables increases, since it’s much easier to keep your data in one

data frame than in separate variables. Suppose your data is captured in

a data frame, such as the dfrm

variable shown here:

> dfrm

y u v w

1 6.584519 0.79939065 2.7971413 4.366557

2 6.425215 -2.31338537 2.7836201 4.515084

3 7.830578 1.71736899 2.7570401 3.865557

4 2.757777 1.27652888 0.4191765 2.547935

5 5.794566 0.39643488 2.3785468 3.265971

6 7.314611 1.82247760 1.8291302 4.518522

7 2.533638 -1.34186107 2.3472593 2.570884

8 8.696910 0.75946803 3.4028180 4.442560

9 6.304464 0.92000133 2.0654513 2.835248

10 8.095094 1.02341093 2.6729252 3.868573

.

. (etc.)

.When we supply dfrm to the

data parameter of lm, R looks for the regression variables in

the columns of the data frame:

> lm(y ~ u + v + w, data=dfrm)

Call:

lm(formula = y ~ u + v + w, data = dfrm)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) u v w

1.4222 1.0359 0.9217 0.7261See Also

See Recipe 1.20 for simple linear regression.

1.22. Getting Regression Statistics

Problem

You want the critical statistics and information regarding your regression, such as R2, the F statistic, confidence intervals for the coefficients, residuals, the ANOVA table, and so forth.

Solution

Save the regression model in a variable, say m:

> m <- lm(y ~ u + v + w)Then, use the following functions to extract regression statistics and information from the model:

anova(m)ANOVA table

coefficients(m)Model coefficients

coef(m)Same as

coefficients(m)confint(m)Confidence intervals for the regression coefficients

deviance(m)Residual sum of squares

effects(m)Vector of orthogonal effects

fitted(m)Vector of fitted y values

residuals(m)Model residuals

resid(m)Same as

residuals(m)summary(m)Key statistics, such as R2, the F statistic, and the residual standard error (σ)

vcov(m)Variance-covariance matrix of the main parameters

Discussion

When I started using R, the documentation said to use the lm function to perform linear regression. So I

did something like this, getting the output shown in Recipe 1.21:

> lm(y ~ u + v + w)

Call:

lm(formula = y ~ u + v + w)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) u v w

1.4222 1.0359 0.9217 0.7261 I was so disappointed! The output was nothing compared to other statistics packages such as SAS. Where is R2? Where are the confidence intervals for the coefficients? Where is the F statistic, its p-value, and the ANOVA table?

Of course, all that information is available—you just have to ask for it. Other statistics systems dump everything and let you wade through it. R is more minimalist. It prints a bare-bones output and lets you request what more you want.

The lm function returns a

model object. You can save the object in a

variable by using the assignment operator (<-). This example assigns the object to the

variable m:

> m <- lm(y ~ u + v + w)From the model object, you can extract important information using

specialized functions. The most important function is summary:

> summary(m)

Call:

lm(formula = y ~ u + v + w)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-3.3965 -0.9472 -0.4708 1.3730 3.1283

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 1.4222 1.4036 1.013 0.32029

u 1.0359 0.2811 3.685 0.00106 **

v 0.9217 0.3787 2.434 0.02211 *

w 0.7261 0.3652 1.988 0.05744 .

---

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1

Residual standard error: 1.625 on 26 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.4981, Adjusted R-squared: 0.4402

F-statistic: 8.603 on 3 and 26 DF, p-value: 0.0003915The summary shows the estimated coefficients. It shows the critical statistics, such as R2, and the F statistic. It also shows an estimate of σ, the standard error of the residuals.

There are also specialized extractor functions for other important information:

- Model coefficients (point estimates)

>

coef(m)(Intercept) u v w 1.4222050 1.0358725 0.9217432 0.7260653- Confidence intervals for model coefficients

>

confint(m)2.5 % 97.5 % (Intercept) -1.46302727 4.307437 u 0.45805053 1.613694 v 0.14332834 1.700158 w -0.02466125 1.476792- Model residuals

>

resid(m)1 2 3 4 5 6 -1.41440465 1.55535335 -0.71853222 -2.22308948 -0.60201283 -0.96217874 7 8 9 10 11 12 -1.52877080 0.12587924 -0.03313637 0.34017869 1.28200521 -0.90242817 13 14 15 16 17 18 2.04481731 1.13630451 -1.19766679 -0.60210494 1.79964497 1.25941264 19 20 21 22 23 24 -2.03323530 1.40337142 -1.25605632 -0.84860707 -0.47307439 -0.76335244 25 26 27 28 29 30 2.16275214 1.53483492 1.65085364 -3.39647629 -0.46853750 3.12825629- Residual sum of squares

>

deviance(m)[1] 68.69616- ANOVA table

>

anova(m)Analysis of Variance Table Response: y Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) u 1 27.916 27.9165 10.5658 0.003178 ** v 1 29.830 29.8299 11.2900 0.002416 ** w 1 10.442 10.4423 3.9522 0.057436 . Residuals 26 68.696 2.6422 --- Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1

If you find it annoying to save the model in a variable, you are welcome to use one-liners such as this:

> summary(lm(y ~ u + v + w))1.23. Diagnosing a Linear Regression

Problem

You have performed a linear regression. Now you want to verify the model’s quality by running diagnostic checks.

Solution

Start by plotting the model object, which will produce several diagnostic plots:

>m <- lm(y ~ x)>plot(m)

Next, identify possible outliers either by looking at the

diagnostic plot of the residuals or by using the outlier.test function of the car package:

>library(car)>outlier.test(m)

Finally, identify any overly influential observations (by using

the influence.measures function, for

example).

Discussion

R fosters the impression that linear regression is easy: just use

the lm function. Yet fitting the data

is only the beginning. It’s your job to decide whether the fitted model

actually works and works well.

Before anything else, you must have a statistically significant model. Check the F statistic from the model summary (Recipe 1.22) and be sure that the p-value is small enough for your purposes. Conventionally, it should be less than 0.05, or else your model is likely meaningless.

Simply plotting the model object produces several useful diagnostic plots:

>m <- lm(y ~ x)>plot(m)

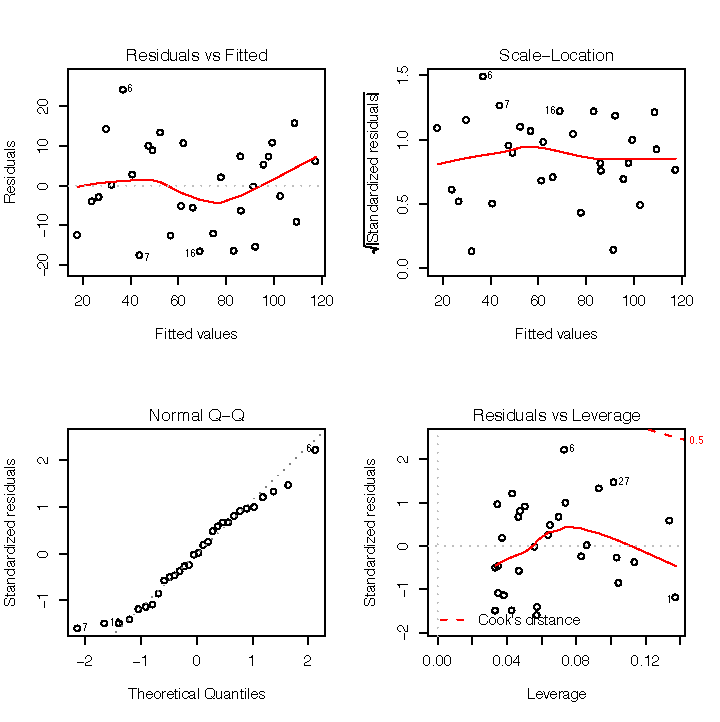

Figure 1-7 shows diagnostic plots for a pretty good regression:

The points in the Residuals vs Fitted plot are randomly scattered with no particular pattern.

The points in the Normal Q–Q plot are more-or-less on the line, indicating that the residuals follow a normal distribution.

In both the Scale–Location plot and the Residuals vs Leverage plots, the points are in a group with none too far from the center.

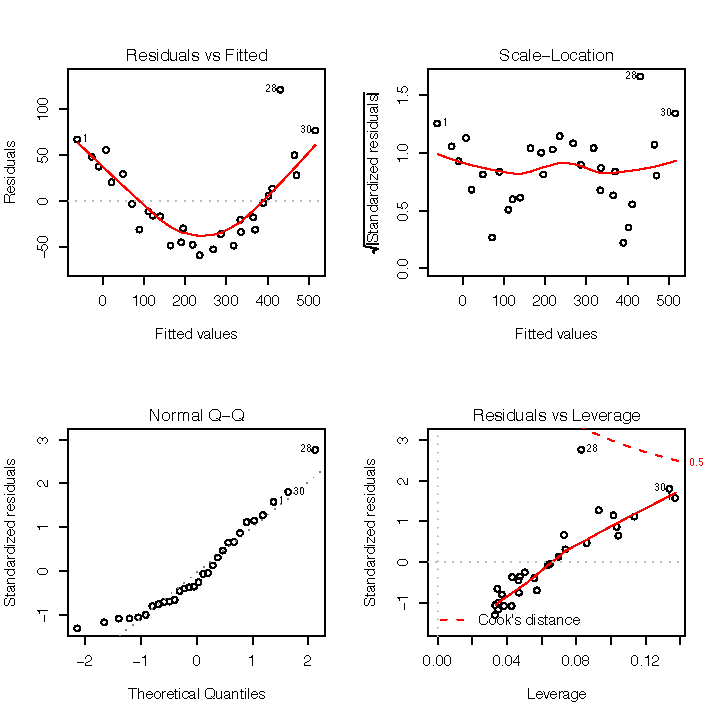

In contrast, Figure 1-8 shows the diagnostics for a not-so-good regression. Observe that the Residuals vs Fitted plot has a definite parabolic shape. This tells us that the model is incomplete: a quadratic factor is missing that could explain more variation in y. Other patterns in residuals are suggestive of additional problems; a cone shape, for example, may indicate nonconstant variance in y. Interpreting those patterns is a bit of an art, so I suggest reviewing a good book on linear regression while evaluating the plot of residuals.

There are other problems with the not-so-good diagnostics. The Normal Q–Q plot has more points off the line than it does for the good regression. Both the Scale–Location and Residuals vs Leverage plots show points scattered away from the center, which suggests that some points have excessive leverage.

Another pattern is that point number 28 sticks out in every plot.

This warns us that something is odd with that observation. The point

could be an outlier, for example. We can check that hunch with the

outlier.test function of the car package:

> outlier.test(m)

max|rstudent| = 3.183304, degrees of freedom = 27,

unadjusted p = 0.003648903, Bonferroni p = 0.1094671

Observation: 28outlier.test identifies the

model’s most outlying observation. In this case, it identified

observation number 28 and so confirmed that it could be an

outlier.

See Also

The car package is not part of

the standard distribution of R; download and install it using the

install.packages function.

1.24. Predicting New Values

Problem

You want to predict new values from your regression model.

Solution

Save the predictor data in a data frame. Use the predict function, setting the newdata parameter to the data frame:

>m <- lm(y ~ u + v + w)>preds <- data.frame(u=3.1, v=4.0, w=5.5)>predict(m, newdata=preds)

Discussion

Once you have a linear model, making predictions is quite easy

because the predict function does all

the heavy lifting. The only annoyance is arranging for a data frame to

contain your data.

The predict function returns a

vector of predicted values with one prediction for every row in the

data. The example in the Solution contains one row, so predict returns one value:

>preds <- data.frame(u=3.1, v=4.0, w=5.5)>predict(m, newdata=preds)1 12.31374

If your predictor data contains several rows, you get one prediction per row:

>preds <- data.frame(+u=c(3.0, 3.1, 3.2, 3.3),+v=c(3.9, 4.0, 4.1, 4.2),+w=c(5.3, 5.5, 5.7, 5.9) )>predict(m, newdata=preds)1 2 3 4 11.97277 12.31374 12.65472 12.99569

In case it’s not obvious, the new data needn’t contain values for response variables, only predictor variables. After all, you are trying to calculate the response, so it would be unreasonable of R to expect you to supply it.

See Also

These are just the point estimates of the predictions. Use the

interval="prediction" argument of

predict to obtain the confidence

intervals.

1.25. Accessing the Functions in a Package

Problem

A package installed on your computer is either a standard package or a package downloaded by you. When you try using functions in the package, however, R cannot find them.

Solution

Use either the library function

or the require function to load the

package into R:

> library(packagename)Discussion

R comes with several standard packages, but not all of them are

automatically loaded when you start R. Likewise, you can download and

install many useful packages from CRAN, but they are not automatically

loaded when you run R. The MASS

package comes standard with R, for example, but you could get this

message when using the lda function

in that package:

> lda(x)

Error: could not find function "lda"R is complaining that it cannot find the lda function among the packages currently

loaded into memory.

When you use the library

function or the require function, R

loads the package into memory and its contents immediately become

available to you:

>lda(f ~ x + y)Error: could not find function "lda" >library(MASS)# Load the MASS library into memory >lda(f ~ x + y)# Now R can find the function Call: lda(f ~ x + y) Prior probabilities of groups: . . (etc.) .

Before calling library, R does

not recognize the function name. Afterward, the package contents are

available and calling the lda

function works.

Notice that you needn’t enclose the package name in quotes.

The require function is nearly

identical to library, but it has two

features that are useful for writing scripts. It returns TRUE if the package was successfully loaded

and FALSE otherwise. It also

generates a mere warning if the load fails—unlike library, which generates an error.

Both functions have a key feature: they do not reload packages that are already loaded, so calling twice for the same package is harmless. This is especially nice for writing scripts. You can write a script to load needed packages while knowing that loaded packages will not be reloaded:

The detach function will unload

a package that is currently loaded.

> detach(package:MASS)Observe that the package name must be qualified, as in package:MASS.

One reason to unload a package is if it contains a function whose name conflicts with a same-named function lower on the search list. When such a conflict occurs, we say the higher function masks the lower function. You no longer “see” the lower function because R stops searching when it finds the higher function. Hence unloading the higher package unmasks the lower name.

See Also

See the search function for

more about the search path.