AS WE HAVE SEEN, games are a powerful medium for designers to communicate with players through visual communication, teaching, and advertising methods. Emotions play a vital role in creating gameplay experiences in levels and can be evoked through the qualities of space—size, orientation, lighting, and views. In this chapter we utilize many of these methods to tell stories with our gamespaces.

Games are unique from other media in their interactivity, allowing players to have agency over their gameplay experience. In the interest of creating dialogs with our players, level designers can utilize the unique opportunities games present both to convey precreated stories with their levels and to allow opportunities for players to create their own stories through gameplay.

In this chapter, we explore how game mechanics and art create storytelling opportunities. We also explore the different types of narrative spaces, as well as how modular level assets can be utilized to create environmental narratives or even show narrative progression. With these elements in mind, we reexamine narrative rewards to illustrate how narrative may be used to allow players opportunities for exploration, discovery, and writing their own narratives through gameplay.

What you will learn in this chapter:

Expressive design

Mechanics vs. motif

Narrative spaces

Environment art storytelling

Materiality and the hero’s journey

Pacing and narrative rewards

In 1607, Emperor Shah Jahan, then the Mughal Prince Khurrum, was betrothed to Arjumand Banu Begum, a granddaughter of Persian nobles. When they were married five years later, Khurrum gave Begum the title of Mumtaz Mahal, the Jewel of the Palace, declaring her “elect among all women of the time.”1 When Mumtaz died in childbirth in 1631, Jahan was inconsolable. Ater two years of grieving, he commissioned a tomb be built for her in Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India. To capture the memory of Mumtaz’s beauty, architects and artisans from around the Muslim world built the tomb with precise proportions and calligraphic ornamentation of passages from the Qur’an.2 The surrounding gardens are based on Persian Charbagh (paradise gardens), with abundant trees, flowers, plants and prominent use of water to represent the four rivers of Paradise.3 The result is the Taj Mahal, one of the most significant and evocative architectural works in human history (Figure 7.1). Through the Taj Mahal’s design, the emperor embodied what he believed to be the beauty of Mumtaz, and an expression of his love for her.

FIGURE 7.1 The Taj Mahal and its surrounding gardens embody a historic love story and the beauty of the woman interred there through ornamentation, proportion, and landscaping.

In a similar—though much more commonplace—case, design guru Donald Norman, in his book Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things, discusses his collection of three unusual teapots, each having a significant narrative or experience.4 One, designed by French artist Jacques Carelman, has the spout on the same side as the handle and is therefore impossible to use. The next, the Nanna Teapot, designed by architect Michael Graves, has a bulbous design of clear glass that shows the tea as it steeps and a tea ball inside that can be raised or lowered with a crank. The third, the Ronnefeldt “Tilting” Teapot, can be stood on its back for steeping, then propped upright for serving (Figure 7.2). Norman keeps the teapots on display because they each evoke different components of product design. However, each also embodies a unique story through the experience of brewing tea: one of snarky impracticality, one offering insight into the transformation of water to tea in an appealing form, and one that describes the readiness of the tea through the practical transformation of the pot itself.

Much like these more classical examples of design—architectural and product design—games have had the power to express narratives, emotions, and ideas. Long before video games gained the expressive power they have today—high-end graphics, media with large storage capacity, sophisticated sound design, and so forth—games, including non-digital ones, embodied a variety of ideas through their mechanics and visual elements. Throughout history, many games have been created to simulate important elements of the cultures from which they originated. Chess, for example, was created in India during the Gupta Empire (ca. 320–600 CE) as Chaturanga, which means “four divisions” (of the military).5 Slave children in the American South played musical, cooperative, and role-play games (not to be confused with role-playing games) to cope with their oppressive surroundings.6

FIGURE 7.2 An illustration of Donald Norman’s teapot collection, as described in the book Emotional Design.

We have looked at level design in games as a tool for communicating with players and we have described game levels as media for teaching or evoking emotional responses such as fear, excitement, or joy. Examples such as the Taj Mahal, Donald Norman’s teapots, and the games of historic cultures, however, show us that design can embody narrative or cultural ideas as well.

Narrative Design and Worldbuilding

As level designers, we should be concerned with finding the connections between narrative development, the embodiment of cultural ideas, and expressions of usable gamespace. A common expression of these factors is worldbuilding, the creation of fictional worlds, geography, and cultures. An important example for game developers comes from the work of J.R.R. Tolkien. Through works such as The Lord of the Rings7 and The Silmarillion,8 Tolkien created Middle Earth: a rich fantasy world beginning with unique languages and then adding political structures and landscapes. As a Rawlinson and Bosworth professor of Anglo-Saxon at Pembroke College, Tolkien specialized in ancient English languages, the Germanic languages, and spoke many others.9 Tolkien acknowledged that languages were central to his works, as Middle Earth was primarily a place for the people who spoke Tolkien’s own constructed languages.10 The cultures he developed influenced his stories and the geography of Middle Earth.

Tolkien’s language-centric works show one methodology for world-building, as one might choose to design a world around politics, as a stage for a specific story, or as a home for specific characters. In the case of Middle Earth, the geography is a stage born out of the varied cultures Tolkien created and their relationships with one another. The design of Middle Earth, both visually and culturally, was one element that lent to the success of The Lord of the Rings and other works based in that world. Through the detailed descriptions the author provided, readers could envision the world of Middle Earth in their minds and eventually through popular media such as cartoons and film. Tolkien’s works, and others like them, would be very influential on narrative-based games, both in setting and in the ability to conjure worlds from designed imaginary elements.

Narrative Worldbuilding in Games

Many modern gamers are familiar with role-playing games thanks to products like Dungeons & Dragons11 or Call of Cthulhu,12 influenced by the works of Tolkien and horror/sci-fi writer H.P. Lovecraft, respectively. In their most basic form, the physical components of these games include sheets on which players can record their character’s abilities, dice, and a guide for the Dungeon Master, the player who runs the game. Gameplay action largely consists of descriptions of events by the Dungeon Master and responses by players, though epic narratives are usually enacted through these exchanges. Far from the flashy visuals of modern video games, these games have endured for decades, and have sold millions of copies. Despite the abstract or text-based nature of these games’ presentations, they share the ability to create meaningful narrative worlds through the imaginations and interactions of players. The histories and events of these worlds are often dependent on the actions of players during game sessions.13

When computers became increasingly accessible in the late 1970s and early 1980s, many role-playing game enthusiasts saw the machines as natural homes for their own designed scenarios: the computer could do the calculations necessary to run the game, allowing players to focus on enjoying the story. Adapting many of their own Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) scenarios to the computer, designers created early computer role-playing games such as Dungeon14 and Akalabeth: World of Doom,15 which even featured designer Richard Garriott’s own D&D character, Lord British. Around the same time, adventure games such as Zork I16 also became popular and featured complex worlds described through text alone (Figure 7.3).

While both computer role-playing games (RPGs) and adventure games utilized simple displays—primitive graphics and text descriptions—they provided engaging narratives that allowed player imaginations to fill in any gaps. While this book has concerned itself largely with level design based on a game’s mechanics, it is important to note that gamespaces may also be conceived through designed expressions of narrative, just as in the examples in architecture, product design, literature, and game design given here. When creating game levels that embody both a game’s mechanics and story, it is important to find a balance between the gameplay-focused (ludic) portions of a game and its narrative elements. In the following sections we explore how this can be accomplished through mechanics, gamespace qualities, and asset placement.

FIGURE 7.3 A portion of the map of Zork I. The game used text descriptions and commands based on the player moving in cardinal directions to create a richly detailed world.

Games are often constructed from core mechanics, the basic actions a player takes in a game. It is this mindset that makes many games fit into the genre of action games, which are commonly defined as games in which a player performs some action to overcome antagonistic entities or hazards.17 However, the history of games is full of many examples of design being constructed in the opposite direction, where mechanics are written to support an existing story. We can understand the comparison of mechanic-based design and narrative-based design as mechanics versus motif, which we explore in this section.

Narrative as a Generator of Design

One prominent example of beginning game design from a narrative is the creation of the original Final Fantasy, the first entry in what is today a lucrative game franchise.18 Hironobu Sakaguchi created Final Fantasy when he was tasked with creating a game to save the nearly bankrupt development studio Square in 1986. Given the freedom to create whatever he wanted, Sakaguchi admitted, “I don’t think I have what it takes to make a good action game. I think I’m better at telling a story.”19 From the story, Sakaguchi embedded a ruleset that supported the narrative structure of the game and allowed traditional elements of epic literature such as quests. The character of Final Fantasy’s gamespaces, shown through environment art, supports the game’s narrative.

In architecture, there is a dissonance between the aesthetics of many buildings and their storytelling abilities. In Chapter 2, “Tools and Techniques for Level Design,” we discussed the parti, the formal generator of many building designs. Starting from parti is a product of the Postmodernist focus on form rather than the narrative experience of the building. Meanwhile, our studies of historic buildings up through examples in Modernist architecture, show a belief in the power of space to create an expressive experience, such as in the approach to the Acropolis, the simulated heavenly kingdoms of Gothic churches, or the concept of man rising above nature embodied in Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s famous Fallingwater parallels Final Fantasy’s development by exemplifying design generated through narrative. Fallingwater was built for Edgar Kaufmann, the owner of a chain of department stores near Pittsburgh. Kaufmann’s family often vacationed on the land near Bear Run, a stream in Fayette County, Pennsylvania, and hired Wright to build them a new weekend house there. Kaufmann had told Wright about his love of the falls at Bear Run and how he used a boulder at the top of the falls as a favorite sunning spot. Wright decided he would build the house on top of the falls and use the sunning boulder as the base of the house’s hearth. The Kaufmanns’ desire to entertain large groups at the house required lots of floor space, so Wright designed Fallingwater with generous cantilevers. Wright began his design as an expression of Kaufmann’s vacation stories and allowed the form of the building to rise, quite literally, from the narrative.

In truth, designs beginning from either mechanics or narrative in games, and designs from form or expression in architecture are all equally valid. However, both become more powerful when supporting one another, such as Sakaguchi designing game mechanics to support Final Fantasy’s story, and Wright designing a summer house around his client’s vacation stories. In this way, designers should strive to find a balance between the game’s mechanics and their motif—visual themes or narrative patterns. To do this, like Wright, level designers can use their designs to embody both existing narratives and the functional narrative of how a space is used.

The first type of gameplay narrative that designers must balance is embedded narrative, the predetermined story that plays out in a game.20 This kind of narrative can be used as a design generator for games. As we have seen, designs are often generated from embedded narratives: the experience of losing someone you love, a favorite vacation spot, or the story of four warriors trying to save the world.

Narrative takes many forms in games. Some games convey narrative through cutscenes or text that is separate from gameplay. Some convey narrative through the art in the game itself or on the packaging. Salen and Zimmerman describe these methods as narrative descriptors, elements that give meaning to game mechanics by placing them contextually in a story.21 Many games separate their mechanics and narratives in such a way that they can exist without one another: the story is ultimately a backdrop for game mechanics. A common assignment for teaching game design in schools is to have students reverse the narrative elements of games, making gritty action games transform into fairy tales or having kid-friendly games switch narratives to become M-rated horror nightmares.

More powerful are the games whose mechanics are an essential part of their narrative experience. The indie game Thomas Was Alone,22 for example, was created to emphasize the concept of friendship. Mike Bithell, the game’s creator, utilized level design and characters with different movement capabilities to enforce this theme, requiring players to utilize each character’s abilities in tandem to finish levels (Figure 7.4). The concept for Assassin’s Creed,23 created by director Patrice Desilets, was based on the life of eleventh-century missionary and assassin Hassan-i-Sabbah.24 From this narrative concept, the game was eventually given mechanics and level design that embodied elements of an assassin’s work: moving stealthily through crowds, scouting locations, and fleeing acrobatically.

FIGURE 7.4 Thomas Was Alone features incredibly simplistic artwork, but the narrative of friendship is enforced primarily in the game’s mechanics with additional characterization through voiceovers.

When working from either mechanics or motif as the foundation of your game and level designs, it is important to create a dialog between the two. For those designers who have the time and resources for such development, it is worth asking what the important narrative elements of your game are, what actions will support the narrative, and whether those actions can be translated into gameplay mechanics. For example, if one were to write the character of a hacker in a Japanese-style role-playing game (JRPG), one would want to understand what types of actions a hacker would take, rather than making the hacker actually play like a JRPG stock character, such as a mage, warrior, or summoner. Assuming that the hacker’s specialty is opening computerized doors and making robot enemies turn on one another, the designer must design levels around this ability: Can the hacker move with stealth through the level, having robots fight for him or her? Can the hacker open passages for rewards that other player characters cannot? And, if this game takes place in the future rather than the medieval fantasy worlds of many RPGs, how does that affect the world and how players interact with it? If the overworld is outer space, can traditional random monster versus character battles work, or should designers invent an alternative? This balancing of mechanics and narrative elements is vital to making these elements work harmoniously.

Mechanics vs. Gameplay Narrative

The element of interactivity lends itself to another type of narrative in games: emergent narrative.25 As players engage the rules of a game system, they create their own series of events that drives the game action forward. The set of actions taken by one player is usually different from the actions of his or her friends or other players around the world. Throughout this book, we have discussed games as second-order design problems—products where the direct behaviors of users that are out of the control of, though guided by, the work of the designer. While this presents a difficulty for designers intending to create specific experiences in their gamespaces, it is not impossible. Designers may guide players toward intended emotional responses, even if the exact experience of these responses is different for every player. A helpful method for laying the foundations of an intended user experience is to establish a gameplay narrative for your levels.

Gameplay narratives address the emergent aspects of game narratives by envisioning the experience of a player interacting with a game level. Designing for the previous section’s embedded narrative would look like this:

This level is set on the planet of Majon, which features an enemy military base and surrounding slum towns. The level progresses from a town square where the characters’ ship lands, then to the planet’s complicated waterworks system. The player characters sneak through this into the base’s main tower. Eventually players reach a large lab halfway up the tower where one of the experiments crashes out of its containment unit, initiating a mini-boss fight. A cutscene after this fight reveals that the game’s main villain is in the base, and the player must fight to the top of the tower. Players fight the main villain at the end of the level with little success, and the level’s story ends when the main characters narrowly escape death in their ship and pass out.

This type of level summary gives several important pieces of information: general information on the setting and locations, an idea of pacing through the progression of verbs (from sneak to fight describing movement through the level), and plot components of the level itself. A gameplay narrative, however, would allude to these narrative elements but also include information on the theoretical experience of a player interacting with the game:

The level opens with a text display that says “Planet Majon.” Players choose two party members to travel with for the level. Play begins in the marketplace of a dilapidated and seedy slum town, where players can move north toward their goal on the map, west and east to explorable areas of the marketplace featuring item shops, and south to return to their ship. Moving north takes players near large lakes of water with pipes emerging upward and terminating into the side of a large tower with severe vertical lines. Entering the water and the pipes takes players through a dimly lit maze where they must open and shut valves to reach the inside of the tower. Inside, they can stealthily kill guards until they reach a lab where a mini-boss fight occurs. After this, enemy encounters increase in frequency and are impossible to sneak past, forcing direct combat. Reaching the top of the tower, players find a large windowed room with rewarding vistas where they will see the narrative end of the level.

This summary, rather than focusing entirely on narrative events, addresses some of what the player does from a gameplay perspective. It also lays out the mechanics of each part of this theoretical level and opportunities for exploration and secrets. Phrases like “dilapidated and seedy slum town” and “dimly lit maze” give hints to the spatial qualities of these areas, describing how a level designer might utilize lighting, textures, soundscapes, or other environmental assets. Such a narrative can even be expanded upon to include information about emotions players should feel as they play certain parts of the level, or experiences they have outside of mechanics (“the player should feel dread as he or she moves through the dark and narrow hallway,” “jumping from the cliff to the brightly colored platforms below should be a joyful experience,” etc.).

We have compared how one would design from narrative rather than from game mechanics and looked at how such a design methodology works with different types of narrative in games. In the next section, we further address the types of spaces used to create these narratives.

Thus far, we have dealt with gamespace as an instrument for supporting game narratives or as the result of the game narrative as a design generator. However, level designs may be used to tell game narratives themselves. In Chapter 6, “Enticing Players with Reward Spaces,” we discussed narrative stages, reward spaces where important narrative events play out. These are only one type of narrative space utilized in games. Designers should be familiar with the following four different types of narrative space and how they embody and support different types of game narratives:

Evocative spaces

Staging spaces

Embedded spaces

Resource-providing spaces

Through these types of spaces, level designers can create exceptionally expressive game worlds.

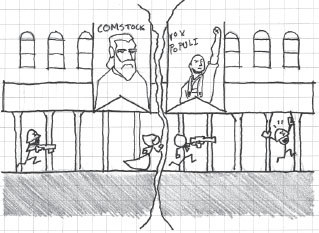

The first type of narrative space was defined by American media scholar Henry Jenkins in his essay “Game Design as Narrative Architecture.”26 Jenkins describes amusement park attractions that use familiar shows, films, or genre traditions as their topic, such as Disney’s Haunted Mansion, Back to the Future,27 and others as evoking audience memories of familiar media. He also describes American McGee’s Alice28 as evoking familiar imagery from Lewis Carroll’s Wonderland stories while providing its own nightmarish take on them. Evocative spaces utilize familiar elements to set a mood, establish the fiction of a game story, or communicate positive or negative events. In the case of Wonderland—a normally cheerful, albeit absurd, place—Alice’s version utilizes twisted recreations of familiar locales, establishing the narrative of a Wonderland ruled by the Queen of Hearts. Similarly, concepts discussed earlier in the book—symbolic assets, intimate spaces, etc.—can be used to describe a game’s narrative state through evocative means. In Bioshock Infinite,29 the character Elizabeth can create alternative versions of the world the game takes place in. In one scene, players jump from the main game world, where the xenophobic government is in control, to an alternate one where rebels have taken control of the city. To establish this switch while allowing gameplay to continue, propaganda posters switch from government focused to rebel focused, while the city architecture remains the same (Figure 7.5). The effect is one of quick transition from a hopeless gunfight to a Les Misérables-esque revolution—the meaning and tone of the environment changes from negative to positive with the swapping of a few textures.

Evocative spaces work because of our understanding of the vernacular, the architectural language of certain locales, established through symbol building. The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. uses the vernacular of European train stations and ghettos to evoke the stories of Holocaust victims (Figure 7.6). Postmodernists such as Michael Graves and Robert Venturi are known for making architectural references to previous works and media in their own work. Michael Graves’s Michael D. Eisner Building at the Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California, for example, evokes both the history of the company and classical architecture through ornamentation. On the façade, Graves used atlas or telamon figures, male counterparts to caryatids—structural columns in the shape of women—of the seven dwarves supporting a large pediment (Figure 7.7).

Vernacular is useful for contrasting evocative art assets with one another in a scene, showing decay, corruption, or the passage of time. The Last of Us30 utilizes the vernacular of urban environments and overgrown forests against one another to create a world twenty years into a zombie apocalypse. Safe zones are mainly urban with militaristic outposts littered throughout, while areas outside the safe zones contrast urban architecture with overgrowth to give a long-abandoned feel.

FIGURE 7.5 Bioshock Infinite shows sudden switches in action through texture swaps in familiar locales.

FIGURE 7.6 The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., built in 1995 and designed by James Ingo Freed. The architecture was designed to mimic post-WWII German architecture.

FIGURE 7.7 The Michael D. Eisner Building (formerly the Team Disney Building) at Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California, completed in 1990.

Evocative vernacular is vital for establishing story, tone, and giving the player some idea of what has happened in a place. A small town with tanks and cars littered through the streets in a zombie game may show that there was at one point a chaotic clash. Vines growing on ruins show that a structure has been long abandoned. When a story becomes more specific, however, subtle environmental storytelling may not be enough. This is why we use the next type of narrative space, staging spaces.

In Chapter 6, we described narrative stages as both enticing and rewarding spaces where a player feels that important game events will happen. Staging spaces are often unique and of large scale. They are easy to see as a player approaches them and often call attention to themselves through monumental architecture or unique features. They may house either gameplay events such as climactic battles or narrative events such as cutscenes, or scripted events where characters move around the player as he or she plays. There may also be staged background events, such as in the intro to The Last of Us, where players run through a linear city streetscape while scripted zombie apocalypse events happen around them.

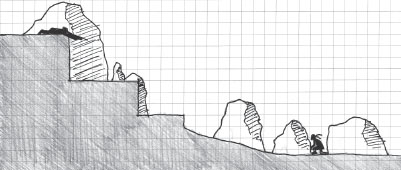

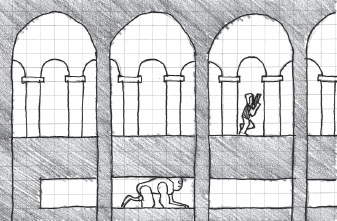

In many ways, staging spaces that are important to actual gameplay can be atmospherically ambiguous. They may be where a player gains an important item, such as the pedestal of the Master Sword in Zelda31 games. They may also be staging spaces for large battles. Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater32 has a unique staging area for two potentially different battle events in the game. In the Sokrovenno region, players either engage in a sniper’s duel with The End, a boss character, or are ambushed by the Ocelot Unit, an elite military group. For these two distinct battle styles, the level needed to have both large-scale outlook points from which players and The End could use sniper rifles and smaller hiding spaces for taking cover during the more active Ocelot fight (Figure 7.8).

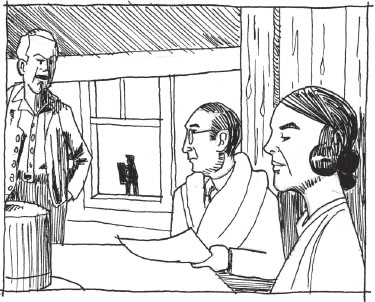

Staging spaces do not have to encompass in-game action, but can be exactly what their name implies: stages. In this way, staging spaces can be set up like the set of a film or play, to support the action that characters are taking within a game. Half-Life 233 utilizes staging space to tell stories and break up intense action throughout the game. Dr. Kleiner’s laboratory near the beginning of the game is a staging space where non-player characters roam and interact with the player and one another, giving expositionary dialog. The scene is set accordingly to evoke a sense of busyness through scattered objects and machine parts. It has places for the events of its specific scene to occur. Such staging spaces are often goals for the player to reach, and can therefore be used as rewards or as a way to control game pacing. In the case of Kleiner’s lab, the player is then directed to escape the city and reach another staging space, Black Mesa East.

FIGURE 7.8 This section of the Sokrovenno region in Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater shows how the space is designed to stage battles of two different scales: a widely scaled sniper duel and a tightly scaled “run and gun” action.

While Kleiner’s lab has elements of a staging space, there are also game objects that allude to experiments prior to the player reaching it or even to the original Half-Life. These types of environmental references bring us to the next type of narrative space.

While there are embedded narratives in games—prescripted stories and scenes that form a game’s primary narrative arc—there can also be embedded narrative spaces, spaces that contain narrative information in the architecture itself. Embedding narrative in architecture is an old tradition. Before the invention of the printing press in the 1450s by Johannes Gutenberg, books were expensive and typically owned by nobles. As a result, much of the population of Western countries was illiterate. Religious officials needed to find a way to expose commoners as well as nobility to the stories in the Bible, so they often stipulated that churches be built with biblical stories embedded in the architecture through sculpture, mosaics, and stained glass windows. Similarly, classical Greek temples often contained relief sculpture in the tympanum of their façades (Figure 7.9). Islamic architecture utilizes calligraphy in many important structures, such as the Taj Mahal and the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. The Dome of the Rock is an embedded narrative space, as it surrounds Mount Moriah, where Abraham is believed to have offered Isaac as a sacrifice, the temple of Solomon is believed to have been built, and Muhammad is believed to have taken his night journey to heaven.34

FIGURE 7.9 Embedding narrative within religious structures has been an architectural tradition for millennia. In many cases, this was a response to the illiteracy of the general populace who worshipped in these buildings—allowing religious narratives to be understood by as many people as possible.

Embedded narrative spaces can be created with environment art by leaving evidence of use by characters or events that previously transpired in the space. Portal35 and Left 4 Dead36 use embedded narratives in their side chambers and safe houses, respectively. In Portal, a character known as the Rat Man hides outside of the testing chambers and leaves used food containers and erratic graffiti for the player to find. These subtle narrative hints develop an entirely unseen character, and foreshadow many of the events in the main narrative. Left 4 Dead players can see the writings of previous survivors who passed through safe houses, leaving information about the zombie plague, establishing the scope of the outbreak, and developing other unseen characters.

The game designers determine these types of narrative spaces and what information they contain. However, we have already established that there is not only embedded narrative, but also emergent narratives. The next type of narrative space will help players take advantage of the potential for players to make their own stories in games.

Previous examples of narrative space have shown how spaces are created to embody narrative context through environment art, spatial quality, or as capsules for character dialog. These examples can, however, be passive if not used in the context of interactive narrative. As discussed throughout this book, both architecture and gamespace have the advantage of interactivity—user interaction gives them meaning. Long after the original creators are gone, buildings may often be repurposed for new uses. For example, Hagia Sophia, a Byzantine church in Istanbul built between 532 and 537 and regarded as one of the most beautiful structures in the world, has been adapted for many uses over the centuries (Figure 7.10). Hagia Sophia was originally constructed as a Byzantine Christian church but was converted to a mosque when the Ottoman Turks conquered Constantinople in 1453, changing the iconography inside to fit Islamic traditions. Since 1935, it has been a museum displaying artifacts and art from the building’s history. This building, as an important cultural and historic landmark, has been adapted over time to fit the purposes of whoever resided in the city and has even been featured in films such as the James Bond movie From Russia with Love. Other adaptive reuses of buildings can be seen in urban redevelopment projects and gentrification efforts, taking something originally for one purpose and using it for another.

FIGURE 7.10 An interior perspective of Hagia Sophia (built 532–537), designed by Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus. The building’s impressive architecture and important cultural status has led it to be a prized possession for conquering forces in Istanbul.

The key element of these examples in providing resources for emergent narrative is that they have some identifiable quality and that they have inherently interactive features. Hagia Sophia is a status symbol. Buildings that are renovated for new uses usually have some marketable quality, such as being on a waterfront or near amenities. In games, landmarks and interactive elements give users incentives to utilize level spaces for more than just travel. In many RPGs and massively multiplayer online RPGs (MMORPGs), towns are important spaces for structured user interaction. Towns such as Goldshire in World of Warcraft37 become hubs for player activity (some positive and some negative) through a central location, being a familiar territory, and having many opportunities for quests and interactions. Games like Ultima Online foster player activity by setting up a morality system through which entry to certain towns is forbidden if one acts hostile to other players. This creates a sense that the game has territories that are unsafe for travel.

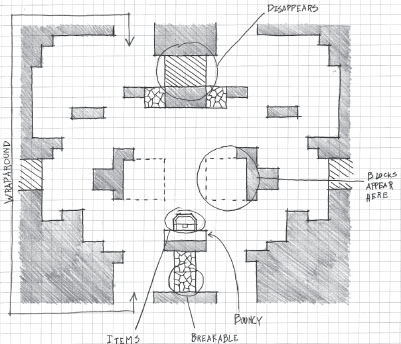

Emergent narrative space is not unique to MMORPGs or other games where large groups of players can interact with one another. Environments that provide many opportunities for interactivity, such as physics objects or other interactive environment pieces, can create some very influential emergent narratives. In the playtesting process for Half-Life 2, testers discovered that it was possible to kill barnacle enemies by allowing them to pick up exploding barrels with their tongues and shooting the barrels as they reached the creatures’ mouths. Valve designers were so delighted by this discovery that they added it to several levels, providing the player with exploding barrels, a downward ramp, and a group of barnacles at the bottom, and called it barnacle bowling.38 Multiplayer party fighting games such as Towerfall39 include many interactive objects in tightly confined arenas (Figure 7.11). The use of these objects gives players various ways of dispatching one another beyond core mechanics, allowing for rich meta-game narratives that are fondly remembered long after players have put the game away (“Dude, remember that time I was about to shoot you but you dropped a crystal ball on my head?”). Some live on for years, such as Lord British’s accidental assassination during the beta-testing of Ultima Online40 or the ill-advised charge of Leeroy Jenkins, a player who famously stormed individually into a boss room designed to be raided by teams in the MMO World of Warcraft.41

So far we have mainly focused on the theory and planning stages of spatial narratives, with a few mentions of practical construction elements such as modular assets and spatial quality. In the next section, we discuss practical methods for creating narrative space with modular assets.

FIGURE 7.11 The arenas in party fighting games such as Towerfall include many interactive objects within a confined space that provide rich opportunities for emergent narratives.

Imagine playing a game where you are walking slowly down a dark hallway, debris crunching under your character’s feet. You walk into what appears to have once been a small lounge. On a table, there is an abandoned gun and a half-filled clip; bullets are scattered around and some have dropped onto the floor. Next to the gun is a tipped-over bottle of whiskey. Under an overturned chair next to the table is a smeared path of blood that leads into another doorway lit up by a spotlight (Figure 7.12). As a player, what do you think happened there? What do you want to do next? How does this scene make you feel?

Storytelling with Modular Assets

This scene may or may not have anything to do with the main plot of the game. Players who open the doorway the blood leads to may or may not find anything inside. What this scene does, however, is create a mini-narrative with environment art. It’s not difficult to imagine that the player may be able to collect the gun and ammunition on the table to bolster his or her own reserves or that these assets are the same ammo assets used throughout the game. However, the placing and arrangement of such assets tell a story: some person was hastily loading a clip when he or she was attacked and dragged off violently. The whiskey bottle provides slight character development and calls into question the skill of the person: was he dragged off because he was drunk, or was the thing so terrifying that he turned to the bottle to calm down? The story told by these objects contains no words, but helps establish tone, creates tension, and provides foreshadowing of things that the player may encounter later in the game.

FIGURE 7.12 This type of scene is incredibly evocative from a narrative standpoint, and can be constructed by arranging prefabricated environment art assets in specific ways. Even if the player has seen similar assets elsewhere in the game, the arrangement is what makes the scene evocative.

As this demonstrates, modular art can be an effective tool for telling environmental narratives as well as communicating between designer and player. As we have seen with our explorations of narrative space, assets embedded into a gamespace can develop unseen characters or provide narrative clues to game action. In games, art assets have the power to be evocative. The designers of Dead Man’s Trail,42 for example, mixed and matched the placement of environmental assets, pickup items, and zombie spawners to create mini-narratives within levels. As players loot for supplies, they come across areas designed to look like unlucky characters had passed through. One such example is in a level with hiking trails: designers scattered hunting rifle ammo around a tent and placed a teddy bear nearby. Zombie spawners were placed such that zombies would appear to come out of the woods—hinting at the fate of the family whose tent the player was looting (Figure 7.13).

FIGURE 7.13 These screenshots from an early version of Dead Man's Trail show how environment art can be used to hint at what has happened in a scene: vehicles and barriers are arranged to look like a terrified bus driver has tried to run through a blockade. Tents, hunting rifles, toys, and zombie spawners are juxtaposed to hint at the story of an unlucky family.

Environment Art and Cinematography

The juxtaposition of contrasting elements—guns and teddy bears, vehicles and barriers, etc.—has a great impact on the type of scene you are creating. The way in which the player views these objects is of utmost importance. Camera is an important consideration for storytelling in games, as level designers can utilize a game’s cinematography to highlight spatial narrative. Cinematography is the study of film techniques, though it is often used to discuss the composition of scenes on film. For game designers, the relationship between camera and object position can be a powerful tool.

When discussing camera usage in games, we discovered that an important element was drawing a player’s attention to environmental elements the designer wished him or her to see. In first-person games, this often includes drawing the player’s view to objects with visual components such as lines, contrasting colors, or lighting. In 2D or top-down games, cinematography can be used to show something to the player that the player’s character may not be aware of—oncoming monsters or objects important to a level’s plot.

An innovator in modern cinematographic storytelling techniques was Orson Welles in his 1941 classic film Citizen Kane.43 Welles used a technique in Citizen Kane known as deep focus, where objects in both the foreground and background are in focus as the result of layering pieces of film on top of each other.44 Two important scenes in Citizen Kane use deep focus or deep focus-like effects to convey narrative that would otherwise be told simply with dialog. The first is a scene where Kane’s mother and father are arguing over whether to put Kane in the care of a wealthy banker or let him grow up in an impoverished Colorado town. As the adults—the father, who does not want to lose Kane, on one side of the room and the mother with the banker on the other—discuss the fate of the boy, he can be seen playing in the snow out of a window positioned between the adults (Figure 7.14). A later scene, composed by shooting a scene twice with the same piece of film to capture both foreground and background in focus, has Kane and an associate finding Kane’s wife passed out from what they discuss as illness, but a medicine bottle and spoon in the foreground reveal to be a suicide attempt (Figure 7.15). Scenarios like this show how assets may be positioned in such a way that they tell environmental narrative outside of the immediate action of a scene.

FIGURE 7.14 An early scene in Citizen Kane positions two arguing factions on either side of a shot, while the object of the argument, a young Charles Foster Kane, is seen through a window in between the two.

FIGURE 7.15 This later scene of the film has the characters finding Kane’s wife unconscious, while the scenery informs the audience that she had attempted suicide by careful placement of a medicine bottle.

While not all games utilize environmental storytelling at the level of subtlety of Citizen Kane, some utilize foreground, background, or even in-game action elements to alert the players to various narrative elements. In Another World,45 the game’s side-scrolling gameplay view is treated as one camera angle of several in a cinematic experience. Early in the game, a large monster can be seen stalking the player through the background of several screens. The “to the side” camera is used to show the player’s alien ally (nicknamed Buddy) evading captors in other corridors while the two characters are separated later in the game (Figure 7.16). The second act of Sonic the Hedgehog 3 and Knuckles’s46 Launch Base Zone depicts the launch of Dr. Robotnik’s super weapon, the Death Egg by including the weapon in the level’s background and having it launch at the level’s end. In a way, the game also offers this launch as a rewarding vista for the players making it through the level, and allows them to watch the climactic launch during a moment of gameplay downtime before a boss fight. Even for games without fixed cameras, such as first- or third-person 3D games, the player’s arrival at embedded environmental object narrative and how it is highlighted through other environmental elements—shadows, lighting, environmental contrast—is vital.

FIGURE 7.16 Another World uses the side-scrolling camera angle as a way to convey what is happening to a friendly character that the player is separated from.

In this section, we have looked at how individual pieces of environment art may be arranged to create environmental narrative. We also looked at the influence of camera position in telling such stories: carefully placing objects in or out of frame so they give players narrative information in addition to the gameplay action on a screen. Next, we look at a traditional story structure popular in games and how environment art can allow players to track their progress in it.

MATERIALITY AND THE HERO’S JOURNEY

In his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces,47 Joseph Campbell describes the idea of the monomyth, a basic pattern that many heroic narratives throughout the world follow. Campbell summarizes the fundamental elements of heroic narratives from different cultures in this way: “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”48

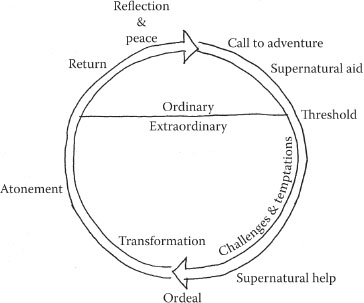

This structure has the hero follow some variation of a call to adventure (which is often initially refused), followed by a road of trials and enemies to overcome. The hero then meets with a supernatural benevolent force (often referred to as the goddess), either realizing that it is a protection he has always had or finding a new protection and being blessed by it. The hero must face a powerful malevolent force, overcoming both its power and the hero’s own demons. The hero must finally gain and escape with a boon of some sort (important quest item) and return to his normal world, where he uses his newfound power to live out his life in peace (Figure 7.17).

FIGURE 7.17 The hero’s journey is a pattern common to narratives of many cultures throughout human history. It is a popular narrative structure for modern video games.

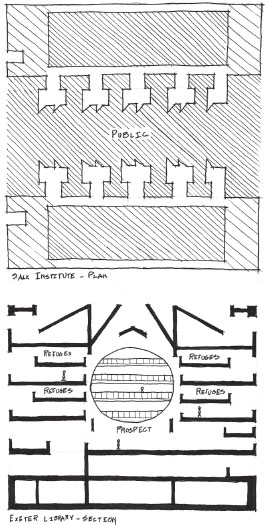

In Origins of Architectural Pleasure, Grant Hildebrand argues that architecture can embody the stages of the hero’s journey with both spatial quality and materiality.49 Hildebrand suggests that in many heroic narratives, landscape makes its challenge to the hero visibly noticeable by being “deficient, one way or another, in support or reassurance.”50 As evidence, he suggests the ruins of Mycenaean forts or the American West as examples of such landscapes, and posits that their visual characteristics help create the heroic narrative itself. Hildebrand argues that buildings such as the Phillips Exeter Library and Salk Institute, both designed by Louis Kahn, embody the hero’s journey through a contrast between intimately scaled “safe” study spaces and “dangerous” public transitory spaces. The study spaces in each building are finished in comfortable wood, carpet, and brick finishes, while the public spaces are finished in cold concrete51 (Figure 7.18). Studies of heroic fiction reveal Hildebrand’s assertions to be valid: Odysseus’s travels take him from the safety of his home in the green lands of Ithaca to war in Troy, around the Aegean, Mediterranean, and Ionian Seas—deserts of water instead of sand—and finally back home.52 Similarly, Frodo Baggins must travel from the comfortable farmland of the Shire and through the increasingly bleak lands of Middle Earth to the volcanic Mount Doom, where he can destroy the evil Sauron’s One Ring in The Lord of the Rings.

FIGURE 7.18 Louis Kahn’s Phillips Exeter Library and Salk Institute both use natural materials such as wood and stone in intimately scaled refuge spaces and harsher materials such as concrete in public spaces.

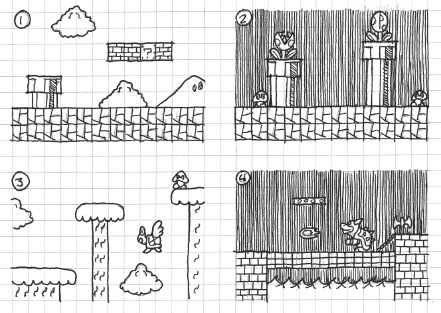

Games often utilize materiality, specifically in the tile art or texturing of a game’s level surfaces, as an indicator of a place’s character and place along a hero’s journey. The original Super Mario Bros. in many ways utilizes a micro-hero’s journeys in each world of the game: Mario begins each world in a comparatively friendly level with cheerful music, trees, bushes, clouds, and few gaps. He then often (not always) descends into an underground world of some sort filled with new dangers: narrower spaces to move in, aggressive enemies, and darker coloration. Upon leaving this, he is in a stage that is aboveground but has more perils: wider gaps, moving ledges, or narrow bridges that test his skills gained in the previous two levels. Finally, he must go to Bowser’s castle where he encounters cold stone, boiling lava, and a climactic battle with Bowser himself. Upon reaching the captive at the end of the world, he is informed, “The Princess is in another castle,” and begins anew (Figure 7.19). Environments in the original The Legend of Zelda53 follow a similar pattern: players begin in a forested area of Hyrule with abundant shops, wander through bleak and dangerous wilderness, and then descend into dimly lit dungeons.

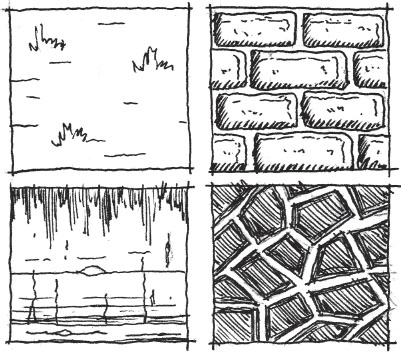

When following a similar pattern in your own games, you can utilize different tile sets and color (diffuse) maps to create the desired environmental effect. Safe or homely places should feature natural or rich materials: grass, wood, brick, stone, and other Wrightian materials. As the hero moves forward in his or her quest, use increasingly harsh or battle-damaged materials: bigger or more roughly hewn stones, machines, alien technologies, iron, lava, acid, etc. (Figure 7.20). It is also fashionable to use “grunge” textures in modern games—textures that show wear, tear, or damage through dirtiness. Grunge is useful for showing corroded or corrupted areas that were once safe, in contrast to safe areas being clean, tidy, and inviting.

FIGURE 7.19 Each world of the original Super Mario Bros. embodies a miniature hero’s journey: (1) Mario begins in a relatively friendly landscape, (2) descends into a darker vault separated from previous comforts, (3) returns to the surface to be tested by the environment, and (4) has a climactic battle where he rescues a captive.

FIGURE 7.20 Tile sets and textures can do a lot to convey a sense of place in game environments. As players move through a hero’s journey, their environment should go from friendly and inviting to harsh or corrupted.

In many ways, movement through a game’s narrative is its own reward. While a great story does not make a bad game good, it can make playing a bad game tolerable. In the final section of this chapter, we look at how expanded narrative can be used for in-game rewards and how narrative rewards can help us pace our game levels.

While we have discussed narrative spaces throughout this chapter and earlier in the book, there has been only brief mention of narrative as a reward. We have discussed narrative stages as rewards in games: places where story events happen and the player can see from a distance. While we have explored the experience of such narrative spaces in terms of exploration, we have not yet viewed them from the standpoint of game pacing.

The Dramatic Arc as a Pacing Tool

In 1863, German novelist and playwright Gustav Freytag wrote Die Technik des Dramas, which studied dramatic stories in five acts: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and dénouement.54 This structure formed what is known today as the dramatic arc, often visualized as a graphic called Freytag’s pyramid (Figure 7.21).

FIGURE 7.21 Freytag’s pyramid shows the stages of the dramatic arc.

The dramatic arc is a useful tool for tracking throughout fiction. Stories can contain one dramatic arc over the course of the entire narrative, or several. In the example of The Lord of the Rings, which was split into three smaller books, The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King, each book has its own dramatic arc. Similarly, each chapter of each book often has a situation that follows its own arc. When Frodo and his party are attacked by Ringwraiths at Weathertop, for example, exposition sets up why the characters are there, the action rises as the Ringwraiths approach, the stabbing of Frodo is the climax, and Aragorn’s driving off of the wraiths and the aftermath of the event are the falling action and dénouement.

Games also use the dramatic arc to tell stories. Donkey Kong55 uses the dramatic arc across its four story levels thus: Exposition is the opening scene where Pauline is shown being kidnapped by Donkey Kong. The rising action is where Mario (then known as Jumpman) pursues Donkey Kong up increasingly complex levels of the skyscraper. The climax comes in the fourth level, where Mario must remove rivets holding Donkey Kong’s platform up, and the falling action and dénouement occur as Donkey Kong himself falls and Mario is reunited with Pauline.55a

In many gamespaces, action is organized into geographic designations: worlds, territories, etc., that have a common thematic factor. Super Mario Bros. games often have eight worlds with a series of sub-levels in each and a castle level at the end. Batman: Arkham City,56 which has a large open world, has territories belonging to members of Batman’s “rogues gallery,” and thus makes each territory represent that character’s gimmick: ice, plants, circuses, etc. In both cases, each territory follows a dramatic arc: Mario must travel through increasingly difficult levels to destroy the Koopa stronghold in each world, and Batman often has a mission to accomplish in each villain’s hideout, which includes twisted puzzles and ends in a climactic confrontation.

Rewarding Exploration with Embedded Narrative

The level-by-level dramatic arcs in these games allow players to move easily through the games. As discussed in Chapter 2, it is important to keep a contrast of high and low action to properly pace a game. By structuring game levels with dramatic arcs—arrive in the level, overcome obstacles and challenges, overcome a large challenge or enemy, reach the goal of the level, emerge victorious—players feel as though they have accomplished something.

Falling action and dénouement are both important elements of this structure for game designers, as they are opportunities for players to slow down and breathe. They are also where we can position rewards for players: a dramatic escape, an item that replenishes lost resources, or a sought-after artifact. Embedded narrative delivered at the end of dramatic arcs helps the player feel as though he or she is making progress through a game, whether this narrative is delivered environmentally, through scripted in-game events or through cutscenes.

This type of pacing also connects narrative structure to long- and short-term goals in games, offering the quest for a short-term goal as a satisfying dramatic arc of its own before pausing and moving on to the next in a larger long-term arc structure.

Rewarding Exploration with Optional Narrative and Easter Eggs

While the dramatic arc structure can give us a feeling for how to structure game levels and reward players by progressing them through a story, there are also opportunities to reward players with optional narrative for exploring gamespace on their own. Optional narratives can be important for games, as they give players additional incentives to test the limits of gamespace and make players feel as though they are privy to privileged information. These types of narratives can be rewards of glory in game levels, the discovery of which can enhance a player’s interaction with a gamespace.

The implementation of these types of narratives often depends on the development resources of studios. For example, The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask57 features a standard Zelda narrative structure: overcome a number of dungeons to gain passage to the final enemy’s stronghold for a climactic showdown. However, the game also allows players the optional quest of collecting masks, which often involves helping non-player characters (NPCs). Many of these side quests have their own embedded narratives, such as one where the player must reunite two estranged lovers. Each mask quest features special characters, text, assets, and animations, making them more robust than many side quests in games.

While the example from Majora’s Mask is possible with a larger development studio, smaller studios may not have the resources for additional content on that level. However, optional narrative rewards can even be created with simplistic storytelling methods. The Rat Man’s hideouts in Portal are technically optional: they are not required for passage through the main game, and a player’s understanding of the story does not suffer if he or she does not find them. However, Valve placed these stories closely enough to the main gamespace that players could find them easily. These assets are much more simplistic: special textures applied to game geometry. For many games, big or small, such assets could be created quickly by an artist, and then added in out-of-the-way places by a level designer.

Another Valve game, Half-Life 2, features an optional character that is a little more difficult to find, the All-Knowing Vortigaunt. By entering a tunnel full of radioactive waste in an early level, players can find this character, who speaks cryptically about in-game events and roasts a head-crab over a fire. Creating such a character is as simple as creating textural optional narratives. The designers used common assets—a vortigaunt alien, a headcrab, and a fire particle effect—and recorded some new lines for the alien to speak.

These are examples of “Easter eggs,” hidden jokes, messages, or other rewards for looking closely at a work. Easter eggs have been used in many media, such as art, film, or software, often with the author hiding himself or herself somewhere in the work. The term Easter egg was coined for this type of hidden object by Atari staff after game programmer Warren Robinett included a hidden room in the 1979 game Adventure. This room contained the message “Created by Warren Robinett,” an act of defiance against bosses who would not let Atari game designers put their names on their work.58

Finding such a reward in a game level, often at great risk, as with the All-Knowing Vortigaunt, or through a complex puzzle, as with the Warren Robinett message, can become an emergent narrative all its own—something for players to brag about to friends. Hiding these types of narrative components in levels can make your own gamespaces fun to interact with both in and out of the game.

In this chapter we have considered level design from another perspective, that of meaning and narrative. We have seen that design is not the product of mechanical prompts alone, but also of stories. We have also seen how spaces, both digital and architectural, tell stories through architectural vernacular, set construction, and art assets, and we have seen how designed space can transform over time as different users interact with it, changing its use or interacting with it in surprising ways.

In terms of constructing levels, we have seen how environment art and prefabricated gameplay assets may be arranged to build narrative and how the positioning of a game’s camera provides opportunity for delivering this narrative. We have also seen how environment art can indicate the progression of players through game narratives, such as those following Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey. And finally, we have explored how story structures such as the dramatic arc can be used as pacing mechanisms, and how narrative can be used as goals and rewards within this pacing, for both required game actions and testing the boundaries of game worlds.

In Chapter 8, we continue our explorations of how players test the limits of game worlds and how communicating them to players helps build realms of possibility.

1. Koch, Ebba, and Richard André Barraud. The Complete Taj Mahal: And the Riverfront Gardens of Agra. London: Thames & Hudson, 2006.

2. Fazio, Michael W., Marian Moffett, and Lawrence Wodehouse. A World History of Architecture. 2nd ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2008.

3. In most Charbagh, the tomb is at the crossing of the canals, since the rivers of Paradise are said to start at a central mountain. Koch suggests that the Yamuna River, which is next to the tomb, and the gardens across from the tomb are an integral part of the Charbagh plan in addition to the garden’s canals.

4. Norman, Donald A. Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things. New York: Basic Books, 2004, pp. 3–6.

5. Murray, H.J.R. A History of Chess. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962.

6. Wiggins, David K. The Play of Slave Children in the Plantation Communities of the Old South, 1820–1860. Journal of Sport History 7, no. 2 (1980): 21–32. (accessed July 1, 2013).

7. Tolkien, J.R.R. The Lord of the Rings. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1967.

8. Tolkien, J.R.R. The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1977.

9. Jeffrey, Henning. On Tolkien: Growing Up with Language. Model Languages 1, no. 8 (1996). http://www.langmaker.com/ml0108.htm.

10. Tolkien, J.R.R., Humphrey Carpenter, and Christopher Tolkien. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981.

11. Dungeons & Dragons. Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson (original designers), 1974. Role-playing game.

12. Call of Cthulhu. Sandy Peterson (original designer), 1981. Role-playing game.

13. Kushner, David. Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Created an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture. New York: Random House, 2003.

14. Dungeon. Don Daglow (designer), ca. 1975. Computer role-playing game on a PDP-10 computer.

15. Akalabeth: World of Doom. Richard Garriott (developer), California Pacific Computer Co. (publisher), ca. 1979. Computer role-playing game on Apple II.

16. Zork I. Infocom (developer and publisher), 1980. Computer text adventure.

17. The term action games is also often understood as games with guns or other trappings of action movies, such as explosions, intense combat, etc. Action games, as a broad genre, is separated into the sub-genres of shooters, platformers, and many others.

18. Final Fantasy. Square (developer and publisher), December 17, 1987. Nintendo Entertainment System game.

19. Final Fantasy Retrospective: Part I. GameTrailers. http://www.gametrailers.com/full-episodes/bx14k1/gt-retrospectives-final-fantasy-retrospective--part-i (accessed July 1, 2013).

20. Jenkins, Henry. Game Design as Narrative Architecture. MIT—Massachusetts Institute of Technology. http://web.mit.edu/cms/People/henry3/games&narrative.html (accessed July 2, 2013).

21. Salen, Katie, and Eric Zimmerman. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003, pp. 399–401.

22. Thomas Was Alone. Mike Bithell (developer and publisher), July 24, 2012. PC game.

23. Assassin’s Creed. Ubisoft Montreal (developer), Ubisoft (publisher), November 13, 2007. Xbox 360 game.

24. The Making Of: Assassin’s Creed. Edge Magazine. http://www.edge-online.com/features/the-making-of-assassins-creed/ (accessed July 2, 2013).

25. Jenkins, Henry. Game Design as Narrative Architecture. MIT—Massachusetts Institute of Technology. http://web.mit.edu/cms/People/henry3/games&narrative.html (accessed July 2, 2013).

26. Jenkins, Henry. Game Design as Narrative Architecture. MIT—Massachusetts Institute of Technology. http://web.mit.edu/cms/People/henry3/games&narrative.html (accessed July 2, 2013).

27. Back to the Future. DVD. Directed by Robert Zemeckis. Universal City, CA: Universal Studios Home Entertainment, 1985.

28. American McGee’s Alice. Rogue Entertainment (developer), Electronic Arts (publisher), October 6, 2000. PC game.

29. Bioshock Infinite. Irrational Games (developer), 2K Games (publisher), March 26, 2013. Xbox 360 game.

30. The Last of Us. Naughty Dog (developer), Sony Computer Entertainment (publisher), June 14, 2013. Playstation 3 game.

31. The Legend of Zelda. Nintendo EAD (developer), Nintendo (publisher), February 21, 1986. Nintendo Entertainment System game.

32. Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater. Konami Computer Entertainment Japan (developer), Konami (publisher), November 17, 2004. Playstation 2 game.

33. Half-Life 2. Valve Corporation (developer and publisher), November 16, 2004. PC game.

34. Fazio, Michael W., Marian Moffett, and Lawrence Wodehouse. A World History of Architecture. 2nd ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2008.

35. Portal. Valve Corporation (developer and publisher), October 9, 2007. PC game.

36. Left 4 Dead. Turtle Rock Studios/Valve South (developer), Valve Corporation (publisher), October 2008. PC game.

37. World of Warcraft. Blizzard Entertainment (developer and publisher), November 23, 2004. PC game.

38. Jacobson, Brian, and David Speyrer. Valve’s Design Process for Creating Half-Life 2. Speech, Game Developers Conference from UBM, San Jose, CA, March 2006.

39. Towerfall. Matt Thorson (developer and publisher), June 25, 2013. Ouya game.

40. Donovan, Tristan. Replay: The History of Video Games. East Sussex, England: Yellow Ant, 2010.

41. Leeroy Jenkins—YouTube. YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LkCNJRfSZBU (accessed July 4, 2013).

42. Dead Man’s Trail. Pie For Breakfast Studios and e4 Software (developers), upcoming in 2014. Mobile game.

43. Citizen Kane. DVD. Directed by Orson Welles. Burbank, CA: Warner Home Video, 1941.

44. Ogle, Patrick L., and Bill Nichols. Technological and Aesthetic Influences upon the Development of Deep Focus Cinematography in the United States. In Movies and Methods. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985, p. 73.

45. Another World. Delphine Software (developer and publisher), 1991. Amiga game.

46. Sonic the Hedgehog 3 and Knuckles. Sonic Team (developer), Sega (publisher), October 18, 1994. Sega Genesis game.

47. Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1949.

48. Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1949, p. 23.

49. Hildebrand, Grant. Origins of Architectural Pleasure. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999, pp. 84–88.

50. Hildebrand, Grant. Origins of Architectural Pleasure. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999, p. 84.

51. Hildebrand, Grant. Origins of Architectural Pleasure. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999, p. 87.

52. Fagles, Robert. The Odyssey. New York: Viking, 1996.

53. The Legend of Zelda. Nintendo (developer and publisher), February 21, 1986. Nintendo Entertainment System game.

54. Freytag, Gustav, and Elias J. MacEwan. Freytag’s Technique of the Drama: An Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art. Internet Archive: Digital Library of Free Books, Movies, Music and Wayback Machine. http://archive.org/details/freytagstechniqu00freyuoft (accessed July 6, 2013).

55. Donkey Kong. Nintendo (developer and publisher), July 9, 1981. Arcade game.

55a. Fullerton, Tracy, Christopher Swain, and Steven Hoffman. Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier Morgan Kaufman, 2008.

56. Batman: Arkham City. Rocksteady Studios (developer), Warner Bros. Interactive (publisher), October 18, 2011. Xbox 360 game.

57. The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask. Nintendo EAD (developer), Nintendo (publisher), October 26, 2000. Nintendo 64 game.

58. Donovan, Tristan. Replay: The History of Video Games. East Sussex, England: Yellow Ant, 2010.