Possibility Spaces and Worldbuilding

You should design each part of the garden tastefully, recalling your memories of how nature presented itself for each feature…. Think over the famous pieces of scenic beauty throughout the land, and … design your garden with the mood of harmony, modeling after the general air of such places.

—FROM SAKUTEIKI, AUTHORSHIP

ATTRIBUTED TO TACHIBANA TOSHITSUNA1

The enjoyment of scenery employs the mind without fatigue and yet exercises it; tranquilizes it and yet enlivens it; and thus, through the influence of the mind over the body, gives the effect of refreshing rest and reinvigoration to the whole system.

—LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT FREDERICK LAW OLMSTEAD2

EMERGENT NARRATIVE is A powerful tool to help game players create their own stories. As we have seen, gamespaces provide the resources for emergent narratives through the use of interactive elements. Designers such as Warren Spector have called games with such richly interactive spaces possibility spaces—interactive worlds that produce emergent possibilities through rules. In addition to previously discussed embedded narrative elements, designers develop game worlds by crafting the rules of how they work and communicate these rules to players through gameplay.

Spatial designers—architects, landscape architects, and garden designers—have their own methods for developing worlds through the orientations of features and materials. In this chapter, we explore how to synthesize the methods of these more classical design fields with the worlds of digital games. We explore how players understand the possibilities present in interactive spaces and how designers inform players about the scope of these spaces. Also, we revisit elements of communication, decision making, and choice to learn how designers make explorable worlds. Lastly, we see how the designers of these worlds break their own rules to create engaging surprises for players to discover.

What you will learn in this chapter:

Understanding immersion and player individuality

Architectural phenomenology and play

Emergent spaces

Miniature garden aesthetic

Japanese garden design and worldbuilding

Offering experiential choice

Degenerative design

UNDERSTANDING IMMERSION AND PLAYER INDIVIDUALITY

We have described games as a second-order design problem in which designers cannot directly control the behavior of a product’s users, but can control the rules of a system that users interact with. The late film critic Roger Ebert famously cited this as a reason that he believed that games were not art—he felt that the player’s ability to control his or her experience of games diminished the designer’s authorship.3 However, many game designers utilize this element of games as a way to build replayability into their products—the ability for players to have varied experiences with a game on repeated interactions. Many designers believe replayability and the potential for users to craft their own experiences in interactive worlds creates immersion, a complete acceptance of virtual game worlds as reality. Others, however, believe that the notion of total immersion defeats the promise of games as media that can be experienced by many different individuals. As we will see, this debate and a similar one within the field of architecture can give us insight into how different players use space and how we can create dialogs between users and a space’s unique qualities.

Immersion is a popular game industry buzzword for a game’s ability to engage players. It is often cited as a goal of designers crafting a game, or as a positive quality. However, as is common with buzzwords, its true meaning is lost in its overuse. Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman turn to the essay “Immersion” by François Dominic Laramee to readdress immersion’s true meaning: “a state in which the player’s mind forgets that it is being subjected to entertainment and instead accepts what it perceives as reality.”4

Salen and Zimmerman respond to Laramee’s definition of immersion with the immersive fallacy, a statement of rejection against true immersion that argues that games instead deal in metacommunication—expressions that take into account their own state of unreality. They use anthropologist Gregory Bateson’s example of a dog biting another in play: the bite signifies a real bite, but is at the same time not a real bite; it is a simulated play of biting. Salen and Zimmerman respond with examples from the games Spin the Bottle and Quake. Players of Spin the Bottle kiss but are not expressing love, just as Quake deathmatch players are shooting one another but do not hate each other.5 While players may be engaged in these games and their dramatic elements, they are aware of the game within the context of the game’s placement in the real world and within the scope of their own life experiences.

As we have seen in our explorations of how players learn within gamespaces, gamespaces themselves hinge on both players’ sensory experience of what is happening in the gamespace itself and their prior experience of the game they are playing or similar games they have previously played. Many players assume upon loading a new first-person game that they will have the same controls as many they have previously experienced: the W, A, S, and D keys control player movement, while the mouse is moved to look around and aim. Many players of old Nintendo Entertainment System games were scandalized when they rented a game that used the B button for jump instead of the traditional A button.

Moving even further away from total immersion in a game, player personalities are often considered when crafting game experiences. Games such as Dragon Quest III6 or Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar7 ask players a series of questions at the beginning of the game to determine the stats of player characters. Numerous studies and published works have referenced player types in games. Richard Bartle famously defined the types achievers, explorers, socializers, and killers to describe the players in multiuser dungeons (MUDs), a type of interactive space he helped create with Roy Trubshaw in 1978.8 The fourth edition of Dungeon Master’s Guide for Dungeons & Dragons describes common “player motivations” and how players functioning as “Dungeon Master,” the player who designs gameplay scenarios and acts as the voice of the game itself, can engage each of these player types.9

FIGURE 8.1 Jason VandenBerghe’s chart for player personality types tracks how players’ personalities react to different domains of play: novelty, challenge, harmony, and stimulation. A player’s answers to what he or she likes in each quadrant result in a simple player personality diagram.

In his Game Developers Conference (GDC) 2013 talk, “Applying the 5 Domains of Play,”10 Ubisoft creative director Jason VandenBerghe expanded the Bartle types to take into account five elements of personality: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. These were compared to the titular five domains of play—novelty, challenge, stimulation, harmony, and threat—to determine where players fit on a chart of the first four domains (threat is left out and applied to its own set of criteria), each divided into four quadrants (Figure 8.1). As players answer where they fit on each quadrant of the chart, they can visualize their player personality on a 4 × 4 grid diagram. VandenBerghe proposes that the test be used as a method for applying “accurate empathy” to a designer’s gameplay, allowing him or her to think like different kinds of players as he or she designs. He visualizes this by likening different styles to well-known fictional characters playing well-known games and says, “Play these games like these people.”

FIGURE 8.1 Jason VandenBerghe’s chart for player personality types tracks how players’ personalities react to different domains of play: novelty, challenge, harmony, and stimulation. A player’s answers to what he or she likes in each quadrant result in a simple player personality diagram.

The suggestion that player personalities factor greatly into the type of character one might build in a game, or that the types of games people play are dependent on their personalities, weighs heavily against the idea of total immersion in games. While the ideas of Bateson, Bartle, and VandenBerghe factor greatly into the subject matter of games themselves, they say little of how users engage gamespace. Architects have been struggling with notions of total spatial immersion versus metacommunication. It is this struggle that will help us explore how the spirit of individual gamespaces can be used in concert with player individuality.

ARCHITECTURAL PHENOMENOLOGY AND PLAY

In Chapter 3, “Basic Gamespaces,” we discussed the concept of genius loci, or “spirit of place.” This element of architectural design challenges designers to give places their own individual character or transmit meaning through unique spatial experiences. While originally referring to a town’s guardian spirit in Roman culture, the term gained its current usage by those applying the philosophy of phenomenology to architecture.

Architectural phenomenology was greatly inspired by the works of German philosopher Martin Heidegger, whose application of phenomenology argued against understanding the world in scientific or objective abstracts, but rather in empirical terms based on one’s sensory information at any given moment.11 Architect Christian Norberg-Schultz applied Heidegger’s thinking to architectural space, arguing that spaces should be understood for their own elements rather than through the lens of previous experience.12 As such, practitioners of architectural phenomenology are often concerned with creating spaces with a strong experiential element or that maximize some element of the building’s site while shutting out exterior influences or symbols. Architect Peter Zumthor, a noted phenomenologist, stated that he begins projects by thinking which emotions or experiences he wishes to convey, while staying true to elements of site and material.13 For one piece, the St. Benedict’s Chapel in Sumvitg, Graubunden, Switzerland (Figure 8.2), he emphasized the wood used to create the building by purposely adding a creaking floorboard. Zumthor described this addition as one that would “exist just below your level of consciousness.”14

Phenomenology’s supporters argue that works such as those by Zumthor are to be enjoyed for their own sake, without influence from a priori knowledge (knowledge known inherently without sensory input). Immersion seems to be the phenomenology of play: enjoying a game without input from the outside world. Some people take the concept of role-play to heart when playing, enacting what they would not in real-life situations, such as being an evil warlord, fighting powerful foes, or playing a member of the opposite sex. On the other hand, Salen and Zimmerman’s immersive fallacy points to even this kind of play as engaging the meta-elements of games.

FIGURE 8.2 Peter Zumthor’s St. Benedict’s Chapel, built in Sumvitg, Graubunden, Switzerland, in 1989, clings to its mountainside site while contrasting against the forms of surrounding vernacular architecture. An intentionally warped floorboard inside emphasizes the materiality of the building.

The phenomenology of gamespace is a mix of self-contained elements that also engage in meta-dialogs with players and culture. On the one hand, we have thus far explored how games utilize symbolic assets to modify player behavior or communicate with players and other cultural elements outside the game itself. On the other hand, level design seeks to emphasize the unique mechanics of games, as phenomenologist architects seek to emphasize the building’s unique materials and experience. Therefore the same elements that work to emphasize the unique parts of the game they are in—modular assets used for behavior modification, asset arrangements for communication, etc.—can also engage meta-elements of games. Game world architecture can help facilitate player interaction, but it can create surprising game events by providing resources for different types of players.

In this sense, gamespace rejects architectural phenomenology. Gamespaces can be encountered by many different people in many different ways. The way that two players interact with a level, even if they share player personalities, will be completely different unless the developer forces players to play in a specific way. While such games better address concerns over authorship of gameplay experiences in games by taking choice away from players, they often are not remembered very fondly or do not have gameplay longevity—replay value.

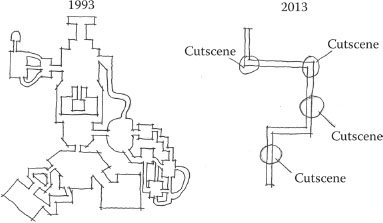

Even games that are ultimately linear, such as those in the Final Fantasy15 series, offer players some choices: character customization, job selection, side quests, etc. When these choices are stripped away, leaving less choice in gameplay, the response is not as warm. This was the case with Final Fantasy XIII.16 In terms of level and world design, the game was much more linear than some considered acceptable, described by some reviewers as a “long hallway.”17 Modern first-person shooter level design has likewise been criticized for being a string of cutscenes and high-action encounters linked by hallways (Figure 8.3). While these spaces may succeed at maximizing a game’s mechanics, they leave little ability for players to create their own experience of the game to compare with others’ own experiences. In this way, we must seek to have a simultaneously phenomenological and metacommunicative approach to level design.

In the next section we further explore the elements of gamespace that allow players of different types to have their own experiences with gamespace and how gamespaces use their phenomenological elements to create emergent experiences.

FIGURE 8.3 A re-creation of a popular Internet image that describes the seemingly complex nature of older first-person shooter maps compared with the linear nature of modern ones.

Throughout the book, we have discussed games as systems. In Rules of Play, Salen and Zimmerman address the complexity of systems through the lens of Jeremy Campbell, author of Grammatical Man.18 Campbell describes complexity in systems as a “special property in its own right” and “enabling them to do things and be things we might not have expected.”19 Since we often understand games as systems, that is, as sets of objects with behaviors and attributes that interact within a space,20 we can say that they have the potential to be complex and do the unexpected things that Campbell describes. If we consider the human players and their wildly divergent personalities as part of the interactive systems of games and space, these systems become increasingly complex. This complexity leads to an element of system that Salen and Zimmerman describe as “crucial” for understanding how systems become meaningful for players21: emergence.

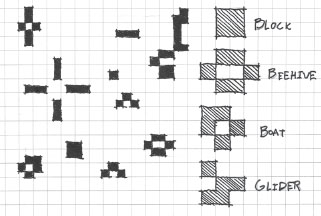

In the previous chapter, we discussed how users interacting with games create emergent narratives, stories created by how one plays a game. As a concept, emergence refers to unexpected outcomes of systems in which unique components interact with one another. One of the most famous examples of emergence in the field of computer science is The Game of Life, a cellular automation created by John Conway in 1970. Conway’s Game of Life is a “zero-player game,” in which a user places a single cell on a large virtual checkerboard and activates the simulation. Rules dictate how living cells interact with dead cells around them, and how the living cells create more living cells. As the simulation runs, geometric patterns emerge due to the rules of the simulation. Some are temporary, while others actually create new cellular bodies (Figure 8.4). While the emergent outcomes of the system are observable when the simulation is playing, they cannot be learned from simply reading the rules of how cells interact. Thus these emergent results are dependent on the interactions of objects within the rules of the simulation.22

Rules and interaction are what make emergent outcomes possible within systems such as architecture and games. In Chapter 7’s example of the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey, cultural and geographic factors led to the church being an important status symbol for conquering armies in the area. Such factors exist outside the structural systems of the building itself (which in the case of Hagia Sophia has created emergent narrative of its own: the central dome has collapsed twice), but are no less part of its history. Likewise, as we have seen, games allow players to create their own emergent narratives as they play; two players’ stories of how they heroically vanquished the same monster are often very different. Through their rules and design, gamespaces offer players possibilities in how they can play, which we discuss next.

FIGURE 8.4 A sketch of Conway’s Game of Life showing different patterns that are emergent results of the automation’s rules.

We have explored the idea of gamespace as emergent worlds from a theoretical perspective, through player personalities, phenomenology, and emergence itself. The question is how to create worlds appropriate for emergent behavior through the largely phenomenological mindset we have used thus far throughout the book: emphasizing a game’s rules and expressive elements through modular symbolic assets. Warren Spector, a designer whose credits include Deus Ex, System Shock, and Wing Commander, was once quoted as saying that games create possibility spaces. Possibility spaces “provide compelling problems within an overarching narrative, afford creative opportunities for dealing with these problems, and then respond to player choices with meaningful consequences.”23

The idea that games are spaces where players can address problems through creative solutions is useful for defining how we must think of game worlds as emergent spaces. As illustrated by Conway’s Game of Life, predefined rules or pieces with programmed behaviors can have unpredictable results. However, that illustration and those like it demonstrate emergence through barely interactive computer simulations. Possibility spaces still address this emergent element of predefined elements of games, but do so in such a way that brings the player into the fold. In Chapter 7, “Storytelling in Gamespace,” we discussed gamespaces that provide resources for emergent narrative and the example of Half-Life 224 playtesters killing barnacles by rolling exploding barrels at them. This action could take place because developers created procedures that allowed these things to happen, placed them in an environment that invited exploration, and allowed players to play. Likewise, players of the original Team Fortress25 discovered that they could jump very high with the soldier class if they jumped into the air and shot one of his rockets downward. This trick, called the rocket jump, became so commonplace in Team Fortress gameplay that it was featured in Valve’s trailer for Team Fortress 2,26 where soldiers fly through the air to synchronized swimming music.

Setting the rules for worlds then allowing players to explore their possibilities is a powerful tool for in-game worldbuilding. Worldbuilding through possibility space encourages the creation of interactive elements that can be given narrative context with art, writing, and other expressive methods. This creates a world that is not only narratively expressive in the way Tolkien’s Middle Earth was, but also interactively expressive in ways that only interactive designed spaces can be. In the next section, we discuss the actual construction of such worlds and how one designer introduces players to them.

In Spore Creature Creator designer Chaim Gingold’s thesis, “Miniature Gardens and Magic Crayons: Games, Spaces, and Worlds,”27 he interprets an often mentioned but never explained aesthetic of legendary designer Shigeru Miyamoto, the miniature garden. According to Gingold, Miyamoto’s miniature gardens reflect the design principles of Japanese gardens: miniaturized worlds in which occupants can explore a “multiplicity of landscapes”28 within a short period of time. Examples include the land of Hyrule in the Zelda series (Figure 8.5), the various environments in Super Mario games, and the explorable alien planets in Pikmin.29 He describes these worlds as complete and self-contained, citing three elements that make them both manageable and believable for players:

Clear boundaries

Overviews

Consistent abstraction30

FIGURE 8.5 The map of Hyrule from The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past has within it a variety of environments for players to explore that are quickly accessible, have clear limits, and are abstracted by their construction with symbolic game assets.

The construction of Miyamoto’s worlds, and how they are introduced to players, factors heavily into their success. As possibility spaces, they have a limited and clear set of rules and objects that the player can interact with in the world. For ease of both a designer’s construction and the players’ ability to understand them (not to mention memory limitations of games), these gamespaces are constructed with modular symbolic assets rather than custom-built. This makes the world and its possibilities easy for players to understand: assets and their variations create a rich system of communication that players come to know as representational of gameplay mechanics. Likewise, keeping this world contained to clear boundaries and a limited set of assets also allows players to learn and interact with the symbolic system more effectively (Figure 8.6). It is the player’s freedom to interact with these symbols, however, that produces the possibility of gameplay emergence.

While Miyamoto’s miniature gardens provide opportunities for player emergence, Gingold also points out that these spaces have methods for

introducing these opportunities to players through linear means. It is this mix of linear and emergent that can show us how to craft the gameplay of our own game worlds.

FIGURE 8.6 Some symbolic assets from A Link to the Past. These objects have a clear meaning and are therefore repeated across the game to allow communication of gameplay possibilities to players.

The first method of introducing possibility space in miniature gardens is through overviews. As stated by Gingold, “Miniature Gardens are scale models of bigger phenomena. Fish tanks and gardens are scale representations of systems bigger than people.”31 The miniature nature of game worlds has not gone unnoticed by writers throughout the history of the medium. In 1983, David Sudnow published Pilgrim in the Microworld, a “stream of conciousness”32 retelling of his experiences with the Atari 2600 game Breakout.33 Sudnow, over the course of several months, feverishly practiced the game until achieving mastery of it. Throughout the book are increasingly complex diagrams of the gameplay mechanics, especially the physics of how the ball and paddle interact with one another.34

Breakout, as with many early video games, has a single-screen structure that conveys a simple overview of the game action. In the first screen from Super Mario Bros.,35 the player can see a variety of important symbols from the game, as well as an enemy and a power-up item. This provides an introduction to many of the rules of Super Mario Bros.’s possibility space that are repeated through subsequent screens and levels.

Both Breakout and Super Mario Bros. are viewed from angles that render game action from outside the game world. In the case of these and other games from the 1970s and 1980s, the metaphor of a fish tank is an apt one: players interact with the game world from a perspective of omnipotence—they can see more than what the game character could conceivably see. This point of view works well in point-and-click adventures such as The Secret of Monkey Island,36 where players must find objects on detailed story screens—any given puzzle can typically be solved with what is visible (Figure 8.7).

FIGURE 8.7 In adventure games like The Secret of Monkey Island, each scene or location conveys its own possibility space. Puzzles are typically solvable with the items visible on the screen during the puzzle itself and with inventory items earned prior to the puzzle.

Top-down games such as The Legend of Zelda and Dragon Quest share this same ability to great effect: designers are not limited to the character’s point of view when showing or hinting at secrets beyond their current geographic location. From a miniature garden perspective, this also affords the ability to give players an overview of game possibilities. In many ways, we can attract players with new possibilities in the same way we do with rewards: by showing something previously unseen in a place that the player must explore to find.

Three-dimensional games such as first- and third-person games in which the player is viewing the game from very close to or from their avatar present their own challenges for integrating overviews. Some games provide a cutscene that flies over the level prior to the beginning of gameplay. In some cases this can be convenient, showing players what they will encounter or even allowing players to find where they should go on a specific mission in a game world that allows lots of otherwise free exploration. However, these can feel artificial and break the sense that the player is in a space where he or she can be surprised or make discoveries.

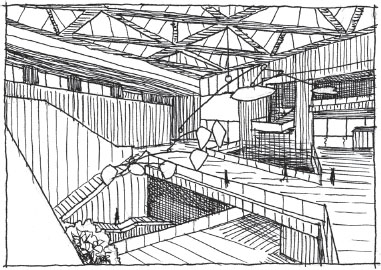

The work of Chinese architect I.M. Pei provides insight into how three-dimensional space can have the overviews common in older video games. In buildings such as the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, Pei uses a glass wall as the façade to show viewers outside what is contained within. Upon entering the building, the museum exhibits are revealed on a series of stacked floors arranged like a collector’s shelves (Figure 8.8). The building provides a summary of its contents with this reveal, but rewards those who explore further with more information.

FIGURE 8.8 The arrangement of floors in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio—designed by I.M. Pei and opened in 1995—gives visitors an overview of the exhibits contained within when they enter the lobby.

Pei’s design for the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., alerts visitors to their options for exploration when they walk into the large atrium (Figure 8.9). Angular balconies and walkways protrude into the space from floors above, offering glimpses of the exhibits contained within, but requiring visitors to explore to receive the full experience. Like the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the overview gives a summary of what is contained within each section of the building but denies full understanding of each exhibit unless the visitor penetrates further into the space.

FIGURE 8.9 A sketch of the atrium of the National Gallery of Art’s East Wing in Washington, D.C.—designed by I.M. Pei and built in 1978. This space offers overviews of the spaces contained in the rest of the museum, but denies full access to them unless the visitor explores further.

As Pei’s architecture shows us, overviews can be accomplished with first- or third-person views through the creation of vistas. These vistas allow players in games to see out over the game world and discover the limits of its possibility space. This is another scenario in which height in level design can be beneficial, allowing players to get an overview of 3D game worlds. In games such as Dragon Quest VIII: Journey of the Cursed King,37 players can often gaze out from the top of cliffs to the world below, seeing distant landmarks. Many worlds in Super Mario 6438 also feature a high point from which players may look out onto the environment, seeing red coins, item boxes, enemies, obstacles, and other gameplay elements. Such vistas go beyond rewards, tactics, or scenery, and can give players an impression of the possibility spaces of 3D worlds. Combined with Lynchian elements such as landmarks, boundaries, and recognizable districts, players can make informed decisions about the path they will take through a space, just as a visitor to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame can plan which exhibits they would like to see first.

While view-based overviews are great ways to convey the possibility spaces of games, they can also be a passive experience. When used too often, they can make the pacing of games feel stagnant. However, Gingold also highlights another form of overview that better utilizes games’ interactivity.

Another method for introducing possibility spaces to players in miniature gardens is the tour. A tour is an initial introduction to gamespaces and their mechanics through a linear level experience. These tours often also show players game mechanics or elements that they may revisit at another time, teasing gameplay to come.39 In the example of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the architecture of the space requires visitors to enter a linear exhibit on the history of rock music after seeing the lobby overview but before actually getting the opportunity to explore the previewed exhibits. Such a tour gives the teased exhibits a sense of historical context and offers the ability to explore them freely as a reward of facility, a reward that offers new abilities.

Game designer Doug Church describes similar experiences in the levels of Super Mario 64. He describes the first power star, the objects in the game whose retrieval is the goal of most levels, requiring that players travel a path that encompasses the entire environment (Figure 8.10). These challenges show previews of other challenges that the player will encounter later, much like the overviews from high places do. Church argues that in subsequent visits to the world, players will know where to find other stars or challenges, as they have already seen much of what the world has to offer.40

FIGURE 8.10 The first star of many worlds in Super Mario 64 often requires players to visit most of the gamespace and teases challenges to come. Some, such as Bob-Omb Battlefield, feature a tour-like exploration of the level that ends with an overview from a high place.

Like Pei’s linear history exhibit in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, tours can also give players an introduction to many of a game’s mechanics without resorting to a ham-handed tutorial where the game talks at the player. In The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past,41 the introduction to the game, where Link must follow his uncle into the dungeons of Hyrule Castle, introduces many of the game’s mechanics: combat, unlocking doors, avoiding pitfalls, pushing and lifting objects, and puzzle solving. Likewise, The Last of Us guides players through a series of challenges that teach the game’s many mechanics—solving environmental puzzles, combat, stealth, and dealing with different zombie types—during the game’s first chapter. Both examples package their tutorials within narrative scenarios rather than training sequences where they are being told the mechanics by another character. This allows players to engage the game’s action right away while acquainting them with the game’s system of mechanics and symbols.

Possibility Space and Procedural Literacy

By now, it should be clear that a primary concern of miniature gardens is allowing players to maximize their possibilities by giving them a thorough understanding of what can be done in the space. In this chapter, we have thus far explored how space can be constructed to introduce what is possible within gamespaces. The introduction of game mechanics in possibility spaces aids the development of what designer Ian Bogost calls procedural literacy.42 Procedural literacy is a familiarity with the rules of a game and how they function within an established possibility space. Symbolic assets are an element of this: players learn that certain level surfaces are solid while others may cause damage. They may learn the identity of items, gates, puzzle elements, objects that can weigh others down, etc. In terms of pure mechanics, this can also translate into an understanding of metrics, character abilities, or when players may encounter obstacles in games. These assets are the building blocks of levels, but are also the procedural language of gamespaces.

Bogost highlights the communicative power of such cause-and-effect procedures, arguing that developing procedural literacy in players can not only allow them to be better players of a certain game, but also help in the creation of procedural rhetoric—using game rules as a system of communication. Game rules and the construction of gamespaces as a system of communication between the designer and player are a central theme of this book: designers must create a dialog with their players to make the best play experience possible. Procedural rhetoric is a tool that many persuasive games, such as those designed by Bogost or Jane McGonigal to solve real-world problems through gameplay, utilize.

Developing both procedural literacy and rhetoric helps players understand gamespaces and their possibilities better. In the previous examples of Super Mario 64 and A Link to the Past, players are guided through the mechanics that they will use throughout the entire game during tour levels. They are also given overviews that allow them to see other gamespaces where these mechanics will be useful.

FIGURE 8.11 The cliff screen in Don’t Look Back comes after a series of simple platforming screens in which the player easily accomplishes everything there is to do in them. As such, the player knows that there are no more gameplay possibilities left to explore when he or she reaches the cliff except to leap from it.

Building procedural literacy and then exhausting player possibilities can create powerful game experiences. A previous example utilized Terry Cavanaugh’s Don’t Look Back43 to discuss uncertainty—the feeling of having no information of how to address game scenarios—and how it may help subvert game design standards. The example of a cliff that the player must jump off of blindly also helps demonstrate how designers can use exhausted game possibilities to guide players through the next steps of a game. Players who reach this cliff know that they have completed everything there is to do in each previous screen, and so know that their only option is to leap off the cliff (Figure 8.11). Tomorrow Corporation’s Little Inferno44 creates a biting satire of free-to-play online and mobile games by restricting players to a very limited set of mechanics: buying and burning objects. Despite colorful descriptions of the many uses of each “buyable” (the game does not allow players to buy things with real money) item, the only thing players can do with them is burn them. This limited possibility space and establishing of procedural literacy allow the game to lampoon the trivial nature of in-game objects that people buy for real money in free-to-play games.

FIGURE 8.11 The cliff screen in Don’t Look Back comes after a series of simple platforming screens in which the player easily accomplishes everything there is to do in them. As such, the player knows that there are no more gameplay possibilities left to explore when he or she reaches the cliff except to leap from it.

Designers must be careful, however, that well-developed procedural literacy does not break the experience of their game. If players can recognize the systemic elements of a game too well, they may dismiss otherwise effective atmosphere-building areas of your levels. In Dead Space,45 for example, players must often traverse narrow ventilation shafts where they cannot attack. Observant players will notice that while they cannot attack, and are otherwise very open to attack, they also never encounter enemies in the vents beyond a few non-confrontational jump scares.

Envisioning levels as possibility spaces is a very effective way to communicate your game’s mechanics to players. Effective possibility spaces introduce a game’s mechanics and system of symbolic assets to players in such a way where they understand symbols when they are repeated. They also give players opportunities for creating their own emergent narratives by becoming procedurally literate about a game and testing the limits of what they can do in your gamespaces. In the next section, we will discuss the aesthetic elements of miniature gardens in games and how they can be used to build exciting game worlds.

JAPANESE GARDEN DESIGN AND WORLDBUILDING

According to Gingold’s interpretation, Miyamoto’s miniature garden aesthetic borrows heavily from the design traditions of Japanese gardens. This is especially true when observing Japanese garden design’s use of boundaries and abstraction. In Secret Teachings in the Art of Japanese Gardens,46 David Slawson explores the purpose of Japanese gardens. In the West, he observes, many Japanese gardens utilize vernacular Japanese architecture: pagodas, torii gates, lanterns, etc., to give the garden “a Disneyland quality.”47 However, the true purpose of such gardens is to give the impression of natural landscapes in a small, explorable area. Depending on the scale one wishes to convey, these landscapes are created through the use of various landscaping features meant to represent natural formations: rocks may be placed as mountains, cliffs, or land forms; raked gravel may be used to represent bodies of water, as may small ponds (Figure 8.12). Vegetation also varies based on the scale of the garden; moss may be used as trees if the garden shows something very far away, or as grass if the garden represents something closer. Small pines are also used to create forest-like areas. Such gardens transport viewers to landscapes outside of their immediate surroundings within quick overviews and tours.

FIGURE 8.12 A turtle rock, formed from a rock with moss in the middle of a small pond, represents an island in the middle of a vast ocean. Such formations demonstrate how landscaping creates simulated landscapes within Japanese gardens.

In video games, Miyamoto’s Mushroom World and Hyrule are primary examples of this. In early Legend of Zelda games, players move through Hyrule in a largely non-linear fashion and may visit a variety of different landscape types: deserts, lakes, forests, mountains, and others within the boundaries of the game world. Super Mario Bros. games feature tours of differing landscapes as each in-game world utilizes a different theme: grass, desert, tropics, ice, etc. New Super Mario Bros. U48 for the Wii U even utilizes the likeness of traditional Chinese scholars’ stones—naturally formed stones with asymmetrical forms and perforations (Figure 8.13) that are popular features in Chinese gardens—as a backdrop for its mountain-themed world. Some of these worlds are largely interactive, such as Hyrule, and others are simply overviews of interactive spaces, such as those in Super Mario Bros. games. This allows us to explore how Japanese gardens treat points of view and what they can tell us about game worlds.

Points of View in Japanese Gardens

In his book, Slawson addresses two types of Japanese gardens—those viewed from fixed vantage points in a building or structure and those that the user can interact with (Figure 8.14). As with camera angles in games, each type offers its own advantages and disadvantages when discussing how one sees the miniature world of the garden. The vantage point gardens allow viewers to see exotic landscapes from outside, giving an overview of everything within. Like 2D top-down or side-scrolling games, they express their worlds through controlled points of view from which the user can take in points of interest. The overworlds of Super Mario games are like these overview gardens, giving an overview of landscapes and describing to the user the types of adventures that may be contained within. In Super Mario Bros. 3,49 each world has its own map that uses symbolic assets to convey to players the contents of each level: numbered blocks denoted normal obstacle courses, forts are mini fortresses full of skeletons and ghosts, mushroom houses yield power-ups, and castles feature boss battles with Bowser’s children. In Super Mario World,50 the maps of each world are linked into one continuous whole, offering players an overview of different landscapes at once (Figure 8.15).

FIGURE 8.13 A scholar’s stone. They are traditional features of Chinese gardens and are formed naturally by water and weather conditions in coastal regions. New Super Mario Bros. U utilizes stones like these as a backdrop for the mountain world portion of its world map, lending to its miniature garden quality.

FIGURE 8.14 Two types of Japanese gardens: ones viewed from outside and ones that are interactive.

FIGURE 8.15 The map of Super Mario World is structured similarly to a vantage point Japanese garden and shows the fictional islands of Dinosaur Land. One might imagine it as a series of rocks with moss and small pines surrounded by raked gravel (as sketched here).

The interactive tea or stroll gardens, on the other hand, allow users to explore their simulated environments. This allows designers to guide users through gardens with communicative views. Hyrule in early Zelda games was a mix of vantage point and stroll garden types. These early games offered overviews based on their point of view that had the Citizen Kane effect of allowing players to see things that their avatar could not. As these games evolved to 3D, they became more purely exploratory spaces, able to take advantage of more traditional viewpoint-based enticement strategies in their designs. The Hyrule of The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time,51 for example, utilizes landmarks in a Kevin Lynch-esque fashion to entice players toward narrative-important quests.

Most importantly, the work of Slawson and his predecessors of over a thousand years gives insight into how game designers may use artificial landscapes and controlled user interaction to create possibility spaces that feel like expansive game worlds. Slawson specifically utilizes two schemas that are of great importance to level designers, scenic effects and sensory effects, which we will briefly explore to understand how Japanese gardens can help us build emergent game worlds.

Slawson’s first schema of Japanese garden design is scenic effects: the ability to create visual representations of memorable landscapes. Historically, Slawson writes, such an element of garden design was important to Japanese aristocrats who traveled to China and Korea during the T’ang Dynasty,52 as it allowed them to re-create sights they had seen in their travels. This, he claims, leads to a feature-oriented design aesthetic, where certain features are re-created to evoke feelings that one has when viewing them in nature.53

Designers therefore often seek to develop scenic effects in such a way that reflect how something would happen in nature. Slawson uses the example of a knarled tree:

A gnarled pine from the mountains (or a similar one from the nursery) serves in the garden not merely as a weathered tree but also, by virtue of the way it is planted in a composition of rocks, as a powerful agent for evoking the atmosphere of craggy mountains far from civilization.54

Creating landscapes in accordance with how they occur in nature helps give landscapes their individual character, or yo. The rocks, plants, water, and earth elements used by designers become a symbolic language through which the Japanese garden designer speaks to viewers about what type of landscape he or she is creating.

Such ideas are important in creating the feeling of possibility space worlds as representations of a landscape and for giving them their own genius loci. When creating game worlds as illustrative landscapes, designers can arrange art assets in a way that reflects the environmental storytelling methods. These, however, can establish the narrative reality of the game world. A world with a properly defined sense of place is a world that players can learn to use. As we have seen, consistent symbolic assets help create a rich system of communication between designer and player. Putting boundaries on this system in a miniature garden helps define the possibilities of a gamespace.

Gingold argues that clear boundaries help miniature gardens be “intelligible and plastic,”55 or understandable and moldable. A game with a clearly defined set of possibilities is easy for someone to pick up and play. Minecraft56 is an excellent example of such a world: clearly defined block objects form the world’s geometry and have clearly defined relationships with one another. From these relationships, many potential combinations of materials are possible. Online players have created everything from giant 8-bit sprites to re-creations of famous real-world and game architecture.

While such elements create visually appealing landscapes in gardens and possibility spaces, they can also be used for creating interesting spatial experiences. Slawson covers this in his next schema.

Slawson’s description of sensory effects in Japanese gardens reflects the ideas that drive much of this book. He discusses the use of scenic elements as a medium for directing the experience of viewers. He also suggests directing visitors through gardens with hearing-based stimuli, like the sound of running water, or with the kinesthetic sensations of touch and movement through spaces. It is in his discussions of garden formations, however, that the lines between Japanese gardens and Gingold’s miniature garden possibility spaces begin to blur.

As we have seen, carefully defining the boundaries of possibility space helps us teach players how to engage our games. Slawson uses the term scroll garden to describe what he and we have been discussing as vantage point gardens, likening the experience of early Japanese gardens to unrolling a scroll and viewing it from above. Such gardens, he states, must fit within a single frame, and he likens them to composing shots on film.57 In the possibility spaces of games, both 2D and 3D, the way in which a designer frames a view can have great impact on how a player understands what he or she is supposed to do.

This emphasis on scene composition addresses a problem that many new designers have when designing miniature garden spaces, exterior environments, and large game worlds: perceived randomness. In nature, trees, rocks, cliffs, and other natural features place themselves over time in unplanned ways. New designers often haphazardly place trees, rocks, and even buildings randomly on their maps, unaware of the importance of their positioning. Directing toward carefully placed scenic assets is how we help players understand our worlds.

FIGURE 8.16 Scenery in miniature garden worlds directs player views across horizontal and vertical planes.

As we saw in our earlier explorations of overviews and tours, many 3D miniature gardens direct the gaze of their players with carefully chosen high points from which the world can be viewed. When composing such views, it is important to understand how to direct the player’s eye throughout your scene. Slawson describes the use of the two visual planes, horizontal and vertical, for this purpose, and recommends engaging both (Figure 8.16). He describes vertical, horizontal, and diagonal forces of objects in a garden, which dictate the direction in which a feature’s energy flows and therefore its ability to point views in a certain direction. In terms of these planes, we have already seen how textural elements on the ground of a game world can direct the player’s eye, such as with stripes of shadows leading into doorways in Half-Life 2. Diagonal forces, representing the visual forces of man in Japanese gardens, can direct views both upward and forward from a player’s point of view. Diagonal elements like landscaping features or fallen debris can both frame and be visual launch pads to important landmarks. These landmarks are typically vertical elements such as tall buildings, mountains, and others, useful for directing user attention58 (Figure 8.17).

It is the relationship between landmarks and the less obvious elements of a view that can truly cement our ability to direct players through game worlds. The orientations of the most noticeable elements and the less noticeable elements are of equal importance to these designers. For example, gardens often feature rocks laid out in horizontal triad (Figure 8.18) and Buddhist triad (Figure 8.19) formations. Horizontal triad rocks are laid in such a way that each formation points to one another, while the formations themselves imply stability through triangular form. These formations emphasize horizontal motion. Buddhist triad rocks show how short complementary rocks emphasize a central landmark rock, highlighting its vertical motion. Supporting this idea, Slawson describes a garden he once watched Professor Kinsaku Nakane build. Professor Nakane first placed a rock of middle height to establish a base height for the composition, and then placed the tallest rock to the right of it.59 An excerpt from the fifteenth-century text Senzui Narabi ni Yagyo no Zu (Illustrations for Designing Mountain, Water, Field, and Hillside Landscapes) illustrates an additional example of such a formation that it calls the master and attendant rocks. The master rock in a formation is the central and tallest figure, while the attendant rocks flank the master rock and are lowered “resembling persons with their heads lowered respectfully saying something to the Master rock.”60 Establishing the size of a middle object to create the normal scale of a scene, and then developing more hierarchically important objects, is a good methodology for environment artists. In any game project, it is important to set up the metrics of your space before creating moments of high gameplay. Without establishing the norm, gameplay or visual elements may be mismatched or unplayable.

FIGURE 8.17 Scenery elements can be said to have forces in Japanese garden design based on how their shape directs the user’s gaze. In games, horizontal forces lead across the horizontal plane of an environment. Vertical forces lead upward and are often used as landmarks, and diagonal forces emanate from the player avatar upward and outward.

FIGURE 8.18 Horizontal triad formation rocks. These rocks mainly address the horizontal plane and imply movement along it.

FIGURE 8.19 Buddhist triad formation rocks. These rocks have a minor triangulation along the horizontal plane but stretch vertically, resembling Buddhist deities as depicted in traditional statues: with two lesser deities flanking a major one.

Through these explorations of vertical and horizontal forces as well as the relationships between landmark assets and the environment around them, we can understand how designers can direct players through large game worlds. Composing views—overview, tour, or simply a normal game view—in such a way that emphasizes choices for player action highlights the actions available within a game’s possibility space (Figure 8.20). When combined with environments that teach players their limits for in-game actions, these create a powerful spatial dynamic between player abilities, environmental choices, and game goals. The levels in Journey61 produce such an effect. Players may run, jump, and glide in the game, and their goal for each area is to reach a gateway to the next area, often situated in a vertically emphasized mountainside. Understanding the limits of their avatar and their goal, players may then roam around the largely open level space, directed by environmental cues—architectural elements, cliffs, rocks, and others—that allow views of one another.

In the next section we further emphasize player choice and discuss spaces that emphasize simultaneously limited but undirected exploration.

FIGURE 8.20 In this theoretical game view, landscaping elements and their directional forces are used to emphasize landmarks on the vertical plane. When forces are combined, they create what Slawson calls a primary force vector.

Gameplay emergence can be a product of both phenomenological elements, such as symbolic assets that are unique to certain games, and the uniqueness that each player brings to all games. We have learned how miniature gardens, spaces that introduce players to their gameplay possibilities and offer the ability to explore multiple landscapes while directing player attention to important features, enable such emergence. Now we will look at spatial orientations that help us develop an awareness of player choice and discuss gamespace types that offer directed choice to players within explorable worlds.

When starting Minecraft, players awaken on an island with no resources and must find shelter before night falls and enemies appear. At this early stage, players may only move, jump, and punch, but may punch anything they wish. Upon punching blocks in the environment, they learn that the blocks break apart, can be collected, and can subsequently be placed elsewhere in the world. Given the short time limit the player has to gather resources on this first day, successful players will seek easy-to-gather resources and make their shelter from them, often a simple hut or hole. However, the next days will see players expanding their resource pool and crafting tools. These tools allow the gathering of more powerful resources and eventually, the crafting of better tools. Eventually, the game opens up and the goal is less one of surviving nightly raids and becomes user defined: users can create what they want in Minecraft’s sandbox world.

In many ways, the single-player experience of Mojang’s Minecraft has much in common with I.M. Pei’s architecture. Like the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the experience of Minecraft begins as one of linear discovery and becomes one of freedom within a defined world. Both works show how one introduces the element of choice in many games by initially guiding players through the rules in a directed or limited manner and then allowing players to explore on their own. In Minecraft, this process introduces players to the game’s symbolic system of blocks. Each has uses and may be combined with other objects and is described by consistent artwork. However, this process also involves the player’s a priori knowledge: gathering wood has certain connotations in human society, as does crafting a sword or pick-axe. The owner of a new pickaxe is likely to seek rock to use it on. This play between linearity and freedom, as well as unique and prior knowledge, helps direct players through the game. In this way, introductions into the symbols that enable player choice both are phenomenological and involve metacommunication. Players are introduced to unique symbols that they can interact with but that invite association with familiar objects.

Beyond the visual symbols themselves, that they were introduced in a limited fashion has much to tell us about the boundaries of miniature garden worlds such as Minecraft and how we introduce large systems of choice to players.

To acclimatize players to its large system of possibilities, Minecraft models choice by giving limited options to players in the beginning, but slowly expands it as players learn new things. At the beginning of the game, players are limited by what resources they can quickly gather, and thus the areas they have access to are limited. As they create new tools and learn more about the world, players gain access to more parts of their island, more resources, and get the impression that their own possibility space is expanding.

Minecraft and other sandbox games, such as Grand Theft Auto IV62 or the previously discussed Little Inferno, carefully limit player choice at first and slowly reveal new possibilities as players master each part of the game. These miniature garden spaces take Gingold’s idea of establishing clear boundaries and use it as a teaching method: imposing limited boundaries at the beginning and expanding them as players learn the game. If these games gave players access to their entire possibility spaces at the beginning, it would be too big, too unintelligible. Framing portions of the world and possibility space into districts helps players master a few commands, and then move on to new ones when they are ready for boundaries to be pushed aside.

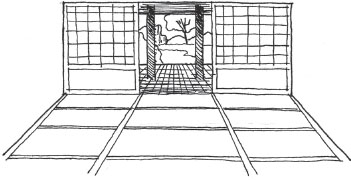

Lyndon and Moore discuss architectural boundaries and breaking them in Chambers for a Memory Palace.63 Humans place boundaries to organize space and mark territory. As Lynch points out, many of these territories have their own individual character that sets them apart from others. Lyndon and Moore go on to explore Japanese design elements such as shoji, rice paper screens that slide to reveal the outdoors, and the lack of interior furniture on tatami mat floors, which suggests continuous interior space. The edges of individual mats work much in the same way that horizontal shadows do, drawing the user’s eye across the horizontal plane of the floor and into the outdoors, which are revealed by an open shoji (Figure 8.21). In game design terms, a player of a game is like the person inside the tatami matted room: he or she must perform the actions one would inside, and can then have the shoji pulled aside to reveal the next part of the environment. The relationship between districts should be established, as the tatami’s horizontal lines draw the eye to the outside, both to transition to the next district and as an act of denial when the player has not yet earned entry to the new district. This gives players a tantalizing goal to look forward to as they explore.

FIGURE 8.21 Japanese houses mark the transition from interior to exterior with a thin membrane of shoji screens. A relationship between these two districts is created by architectural details that draw the eye from one district to another.

Shaping Choice, Risk, and Reward

The border between these distinct districts—outdoors and indoors—gives occupants a choice of whether to remain indoors and view from within, or to explore the newly revealed environment. Outdoors may offer more possibilities for movement than the previous confines of the indoor space. Such is true of sandbox environments: players in Grand Theft Auto IV initially take on missions within a limited area of Liberty City, but are introduced to new districts as the game progresses. As they master the choices available to them in one district, new districts and new choices open up (Figure 8.22).

When developing such environments, designers can treat the borders between districts as skill gates that remain closed until the player has learned all there is to learn in the first district. The mastery of the last skill of a district acts as a trigger to open the path to the next one. Earthbound64 for the Super Nintendo addresses this dynamic in an amusingly self-aware way, having police characters barricade the paths from town to town, claiming that it is their “claim to fame.” These barricades are not removed until the player completes the main quests in each town or powers himself or herself up to appropriate levels to survive the next area of the game. Once each barricade is overcome, the world becomes openly explorable. In sandbox worlds, this often means that the player has agency to test all of the world’s limits: Grand Theft Auto players can spend hours piloting boats and helicopters, Minecraft players can build their own structures, etc.

FIGURE 8.22 Grand Theft Auto IV’s districts each contain a set amount of tasks to perform before a new one is opened up. This forces players to master the possibilities of one space before moving on to the next one that offers additional choices.

Behavioral biologist Karen Pryor calls this process of slowly introducing new information on a set of actions shaping. Shaping, she argues, takes the components of a complex action and breaks them into steps that can be individually mastered and built on. Her process of shaping behaviors focuses on increasing the criteria for positive feedback as new actions are learned: a reward is given first for something simple and then for increasingly complex steps. She argues for each action to be taught one at a time in isolation. She likens this method to learning a golf swing: players first learn how to grip the club, and then learn successive parts of the action. Rewards are given at first for mastering the grip, then for having a proper grip and backswing, then for properly moving from grip and backswing through to proper weight shifting, and so on. Lessons are kept interesting by keeping tasks “ahead of the subject”—always teaching the next action as each is learned rather than resting on already mastered ones.65

Shaping choice in the way that miniature garden games do allows players to understand the certain, uncertain, and risky elements of worlds. By understanding the choices available to them, players are able to interpret the best path to take when given a choice—elements they are familiar with lead them on paths where they can take educated risks or engage in actions they are certain they can perform. However, such gamespaces can subvert these choices by offering little indication of what is down multiple pathways. In the case of Earthbound, caves and dungeons often show multiple passageways on one screen (Figure 8.23) without indicators as to what the correct passage is to reach the end. In these cases where the game has shaped players’ understanding of its possibility space, players are actually motivated to explore all of these passages in case one could contain extra treasures, despite the possibility that they could be attacked.

Beyond their use in role-playing and sandbox worlds, shaping, choices, and risks are also the basis of game worlds that offer both linear progression and opportunities for player exploration. These worlds deserve their own investigation as they create very dynamic spaces driven by rewards and expanding possibility.

FIGURE 8.23 This sketch of the Giant Step level of Earthbound shows how players are offered multiple passageways through a level with no indication of which one to take. Rather than making players uncomfortable with how to move on, such choices motivate players to try all of them if the designer has properly introduce his or her game’s possibility space—risking spending extra time and resources in the dungeon to reap potential rewards.

Throughout the book, we have discussed games in the Metroid series and their unique style of gamespace popularly dubbed Metroidvania—so named for their use in the Metroid and Castlevania series. These spaces are mazes, as discussed in Chapter 3, tour puzzles with multiple branching pathways and dead ends. They are also miniature garden-like in that they have distinct districts and boundaries that offer players the opportunity to explore multiple environment types. Finally, they employ the shaping and expanding possibility spaces of sandbox worlds: players begin in confined areas with a limited amount of abilities and gain access to new areas as they learn new moves (Figure 8.24).

In addition to Metroidvania, we might call such worlds reward-possibility mazes, as movement through them is facilitated through exploration and rewards. Levels in these games greatly employ denial methods to goad players into exploration. Players who explore such mazes are rewarded with power-ups, such as expanded jumping capabilities, better armor, or new weapons that allow access to new areas.

FIGURE 8.24 This sketch of the map from Metroid shows how areas are divided into distinct districts and also inaccessible without specific abilities. These worlds are both miniature gardens and shaping spaces that expand as players gain new powers.

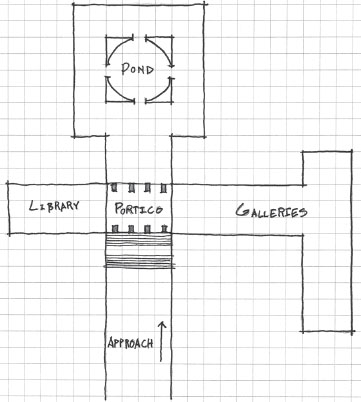

The reliance on rewards for advancement makes finding them critical to moving through the game. As such, these games often employ the risk-reward uncertainty described in the previous section’s Earthbound example: showing multiple passages without specifying which one is correct. We may call these uncertainty nodes. Lyndon and Moore describe such a node in Eliel Saarinen’s Cranbrook Academy of Art. At the end of an important axis on the grounds, Saarinen placed a portico that opens to a pond on the north side, the Cranbrook Art Museum to the east, and the Cranbrook Academy of Art Library to the west (Figure 8.25). This portico, as the climax of the axis, offers a choice of spaces rather than one distinct one. Each path likewise offers its own rich opportunities for exploration rather than a singular space.66

FIGURE 8.25 Eliel Saarinen’s Cranbrook Academy of Art, built in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, in the 1940s. These sketches show how the portico at the end of an important axis on the grounds offers a choice between multiple spatial experiences. Each choice is hierarchically equal to one another, and therefore leaves the choice completely to the occupant.

Reward-possibility mazes rely on uncertainty nodes to encourage backtracking. If a player chooses a particular path and discovers a new power along the way, he or she is often encouraged to return to explore previously visited spaces with his or her newfound powers. Many of these spaces have a particular spatial orientation or visual symbol associated with them. In Super Metroid,67 for example, players may from the beginning of the game uncover hidden blocks with weapon symbols drawn onto them (Figure 8.26). These assets consistently appear throughout the game and show players which tool they will eventually find that will allow them to break through. Once the required ability is found, the game shows the player that his or her new power destroys blocks of a certain type, encouraging players to backtrack and enter previously inaccessible areas. The blocks for the Speed Booster are an example of these kinds of symbols. Batman: Arkham Asylum68 utilizes actual level geometry as symbols for using specific tools. Batman’s Line Launcher, for example, allows him to cross long horizontal pits over which he cannot gain enough verticality to cross with his default glide. These are introduced soon before Batman gains the launcher. When it is finally received, players know that the mysteriously uncrossable gaps are now within Batman’s range of metric possibilities.

FIGURE 8.26 Super Metroid uses symbolic assets to show players what tool to use to destroy barriers long before they have the proper tool. When players finally gain the tool and understand what wall types to use it on, they can backtrack to open new areas.

Much of how players understand reward-possibility mazes and miniature gardens depends on how designers inform them about the rules of these worlds. However, there are instances where breaking one’s own rules can be advantageous. In the last section of this chapter, we discuss the benefits of defining rules and then breaking them.

We have described how designers can build possibility spaces by clearly defining and communicating the rules of game worlds to players, and then letting them have rein to explore them. Such spaces may offer plenty of opportunity for players to stay occupied with possibility space worlds. However, as we saw in the previous chapter, hidden surprises beyond the boundaries of established gamespaces can offer an incredible sense of discovery for players that would otherwise be testing the limits of your game worlds without reward.

Throughout this and other chapters, we have discussed ways to encourage players to explore our games: enticing with denial, rewards, uncertainty nodes, etc. Shigeru Miyamoto’s quote from Game Over: Press Start to Continue that prefaced Chapter 6 applies here: “What if something appears that should not, according to our game rules, exist?”69 Such is the purpose of degenerative design, design that breaks the established rules of a game and gamespace.

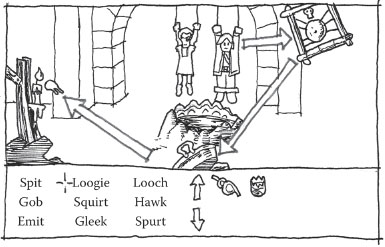

Salen and Zimmerman use the term degenerate strategies to describe what is commonly known as cheating: utilizing hacks and loopholes in game rules to gain an advantage. In some ways, these can break the reality of the game world, allowing players to move outside its boundaries or uncover the world’s artificiality. These may also gain these players an unfair advantage over players who are playing by the rules, which can ruin the experience of playing games.70 Degenerate strategies, however, also allow opportunities for creative strategies within the rules of a game—rocket jumping in Team Fortress, barnacle bowling in Half-Life 2, and bomb jumping in Metroid—that become beloved parts of their games.

Gingold references degenerative design when he discusses the concept of hide-and-reveal, the revelation of new spaces when players test the boundaries of miniature gardens. He uses the work of Miyamoto as an example, emphasizing his ability to “tease, goad, and lure” players into finding unforeseen areas in his worlds.71

Super Mario Bros. is a notable example of hide and reveal, as its place in the history of games and the comparison of its spaces and those of its contemporaries reveal the power of its own degenerative design. Super Mario Bros. was one of the first games to feature horizontally scrolling levels that were unique to one another: many players had not seen such gamespaces before. In this way, the ability to scroll left to right already broke many previous gameplay boundaries. However, players who ducked on pipes could find underground passages. Players who jumped in certain spots or at certain blocks that appeared to be plain brick were likewise rewarded with secret treasures or beanstalks into secret cloud worlds. In Super Mario Bros., Miyamoto established that the screen scrolled left to right, that question blocks held items and that brick blocks did not, and then completely threw these rules out the window to surprise and delight players. Once these were a part of the understood logic of Mario games, new logic was offered in subsequent titles, such as the white blocks players could duck behind and shortcuts under quicksand found in Super Mario Bros. 3. When designers establish rules, they should also be open to the idea of breaking them in ways that do not break the logic of the game, but instead provide exciting discoveries for players.

In this chapter we have discussed the assumptions of game players, writers, and spatial designers regarding how designed spaces respond to the world around them. We have learned how the design elements described in other chapters support the idea of games as self-contained immersive systems, but how their reliance on players make them systems for metacommunication. We have studied how these competing relationships offer the opportunity for distinct play styles and unique occurrences that result from the rules of games, known as emergence. Emergent elements of games highlight how games are not simply containers for linear stories, but also spaces that offer interactive possibilities to players.

These spaces of possibility are enhanced by visualizing the space as miniature garden worlds that contain myriad environments for players to explore. Visualizing these spaces as miniature gardens in the Japanese tradition gives us guidelines on how to introduce possibility to players: overviews, tours, and defined but ever-expanding boundaries. Japanese garden design also informs the way we direct players through these spaces: through the careful design and placement of landscape features and level geometry that highlights and emphasizes places of interest.

Such miniature garden worlds and possibility spaces benefit from the designer limiting player interaction until they are ready to learn more about the world’s possibilities. We explored this idea as shaping, teaching by slowly introducing the elements of possibility within a space. Worlds that teach through direction but also entice exploration through uncertainty form reward-possibility mazes, which reinforce exploration through rewards and shaping through denied access to new areas until rewards are earned. These spaces also encourage risk taking, as they present players with multiple, equally enticing paths.

Finally, we learned how despite the discussion of setting up, teaching, and creating possibility through rules, designers should embrace opportunities to also break their own rules. These expand the possibility spaces of games in ways often delightful to players, and reward those who test the limits of game worlds.

In Chapter 9, we explore multiplayer interaction through urban design principles for mixed-use neighborhoods.

1. Tanaka, Tan. Early Japanese Horticultural Treatises and Pure Land Buddhist Style: Sakuteki and Its Background in Ancient Japan and China. In Garden History: Issues, Approaches, Methods, ed. John Dixon Hunt. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1992, p. 79.

2. Slawson, David A. Secret Teachings in the Art of Japanese Gardens: Design Principles, Aesthetic Values. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1987, p. 125.

3. Ebert, Roger. Games vs. Art: Ebert vs. Barker | Roger Ebert’s Journal | Roger Ebert. Movie Reviews and Ratings by Film Critic Roger Ebert | Roger Ebert. http://www.rogerebert.com/rogers-journal/games-vs-art-ebert-vs-barker (accessed July 14, 2013).

4. Salen, Katie, and Eric Zimmerman. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003, p. 450.

5. Salen, Katie, and Eric Zimmerman. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003, p. 449.

6. Dragon Quest III. Chunsoft (developer), Enix (publisher), June 12, 1991. Nintendo Entertainment System game.

7. Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar. Origin Systems (developer and publisher), September 16, 1985. PC game.

8. Bartle, Richard. Hearts, Clubs, Diamonds, Spades: Players Who Suit MUDs. MUSE: Multi-Users Entertainment Limited. www.mud.co.uk/richard/hcds.htm (accessed July 14, 2013).

9. Wyatt, James. Dungeon Master’s Guide. Renton, WA: Wizards of the Coast, 2008, pp. 8–10.

10. VandenBerghe, Jason. Applying the 5 Domains of Play. Speech given at Game Developers Conference from UBM, San Francisco, CA, March 27, 2013.

11. Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. New York: Harper, 1962.

12. Norberg-Schulz, Christian. Genius Loci: Toward a Phenomenology of Architecture. New York: Rizzoli, 1980.

13. Buchanan, Peter. The Big Rethink: Lessons from Peter Zumthor and Other Living Masters | Campaign | Architectural Review. The Architectural Review. http://www.architectural-review.com/the-big-rethink-lessons-from-peter-zumthor-and-other-living-masters/8634689.article (accessed July 14, 2013).

14. Kimmelman, Michael. The Ascension of Peter Zumthor. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/13/magazine/mag-13zumthor-t.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 (accessed July 15, 2013).

15. Final Fantasy. Square (developer and publisher), December 17, 1987. Nintendo Entertainment System game.

16. Final Fantasy XIII. Square Enix (developer and publisher), March 9, 2010. Playstation 3 game.

17. Glasser, A.J. Final Fantasy XIII Review. Game Pro. http://www.gamepro.com (accessed July 18, 2013).

18. Campbell, Jeremy. Grammatical Man: Information, Language, and Life. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1982.

19. Campbell, Jeremy. Grammatical Man: Information, Language, and Life. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1982, p. 102.

20. Salen, Katie, and Eric Zimmerman. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003, p. 51.

21. Salen, Katie, and Eric Zimmerman. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003, p. 158.

22. Salen, Katie, and Eric Zimmerman. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003, p. 162.

23. Squire, Kurt, and Henry Jenkins. Henry Jenkins. MIT—Massachusetts Institute of Technology. http://web.mit.edu/cms/People/henry3/contested-spaces.html (accessed July 18, 2013).

24. Half-Life 2. Valve Corporation (developer and publisher), November 16, 2004. PC game.

25. Team Fortress. Team Fortress Software (developer and publisher), August 24, 1996. Multiplayer Quake mod for PC.

26. Team Fortress 2. Valve Corporation (developer and publisher), October 9, 2007. PC game.

27. Gingold, Chaim. Miniature Gardens and Magic Crayons: Games, Spaces, and Worlds. Master’s thesis, Georgia Institute of Technology, 2003.

28. Gingold, Chaim. Miniature Gardens and Magic Crayons: Games, Spaces, and Worlds. Master’s thesis, Georgia Institute of Technology, 2003, p. 7.

29. Pikmin. Nintendo EAD (developer), Nintendo (publisher), December 2, 2001. Nintendo GameCube game. It is worth noting that this game was inspired by Miyamoto’s own gardening hobby. In many ways, the comparison to a miniature garden is very literal here, as the environments in Pikmin are conceived as gardens where the miniaturized player and Pikmin can explore.

30. Gingold, Chaim. Miniature Gardens and Magic Crayons: Games, Spaces, and Worlds. Master’s thesis, Georgia Institute of Technology, 2003, pp. 7–8.

31. Gingold, Chaim. Miniature Gardens and Magic Crayons: Games, Spaces, and Worlds. Master’s thesis, Georgia Institute of Technology, 2003, p. 9.

32. Anthropy, Anna. Pilgrim in the Microworld. Auntie pixelante. http://www.auntiepixelante.com/?p=1244 (accessed July 19, 2013).

33. Breakout. Atari (developer and publisher), 1978. Atari 2600 game.

34. Sudnow, David. Pilgrim in the Microworld. New York: Warner Books, 1983.

35. Super Mario Bros. Nintendo (developer and publisher), September 13, 1985. Nintendo Entertainment System game.

36. The Secret of Monkey Island. Lucasfilm Games (developer), Lucasarts (publisher), October 1990. PC game.

37. Dragon Quest VIII: Journey of the Cursed King. Level-5 (developer), Square Enix (publisher), November 15, 2005. Playstation 2 game.

38. Super Mario 64. Nintendo EAD (developer), Nintendo (publisher), September 26, 1996. Nintendo 64 game.

39. Gingold, Chaim. Miniature Gardens and Magic Crayons: Games, Spaces, and Worlds. Master’s thesis, Georgia Institute of Technology, 2003, p. 12.

40. Church, Doug. Formal Abstract Design Tools. Gamasutra. http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/131764/formal_abstract_design_tools.php?print=1 (accessed July 20, 2013).

41. The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past. Nintendo EAD (developer), Nintendo (publisher), November 21, 1991. Super Nintendo game.

42. Bogost, Ian. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007, p. 64.

43. Don’t Look Back. Distractionware (developer), Kongregate (publisher), 2009. Internet Flash game. http://www.distractionware.com/games/flash/dontlookback/.