Influencing Social Interaction with Level Design

A good city street neighborhood achieves a marvel of balance between its people’s determination to have essential privacy and their simultaneous wishes for differing degrees of contact, enjoyment or help from the people around.

—JANE JACOBS, FROM THE DEATH AND LIFE OF

GREAT AMERICAN CITIES1

You have to design and program differently. Combat action in an MMO is so different to combat in a first-person shooter.

—JOHN ROMERO2

THUS FAR, WE HAVE explored level design from a generalist point of view, not focusing on any specific genre or play style. Rather, we have looked at how games may use architectural design principles and engage players cognitively through spatial means. While not a specific genre, multiplayer environments—environments in which more than one player is active at one time—deserve their own investigation.

Like the levels of all games, multiplayer gamespaces exist to embody a game’s mechanics. Whether the game is a first-person shooter game or a massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG), it must embody the actions players take in it: shooting, running, exploring, dungeon crawling, etc. However, games must do so in a way that supports multiple players, either simultaneously or in turns, competitively, cooperatively, or merely coexisting, all in the same space. Beyond having the players in the space, designers of multiplayer levels must also address how to have players within these spaces interact with one another meaningfully.

Urban design professionals have been tackling many of the same challenges for decades. In this chapter we explore several urban design ideas and precedents, and learn how the structures of multiplayer game worlds can help facilitate player interaction.

What you will learn in this chapter:

Emergence and social interaction

Learning from urban emergence

The importance of spawn points and quest hubs

Houses, homes, and hometowns in games

EMERGENCE AND SOCIAL INTERACTION

There is nothing more emergent than the interaction between people. If emergent systems such as Conway’s Game of Life are the result of exact and perfectly performed rules on a computer, they are much less dramatic than the interactions between human beings. Humans have moods, ups and downs, varying states of health, aches, pains, and varied personal histories that all influence how successful they are at interacting or playing with others.

Let us once again consider Ubisoft creative director Jason VandenBerghe’s player type model from “Applying the 5 Domains of Play.”3 VandenBerghe’s player personality elements were openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. The five domains of play were novelty, challenge, stimulation, harmony, and threat. The player elements respectively correspond with:

How players feel about entering into a game experience

How they address tasks in the game

Whether they play best alone or with others

Whether they care about a larger narrative

Personal sensitivity to in-game events

Similarly, the domains of play correspond with factors of how game worlds are constructed:

How many interesting things are there to see?

Are challenges immediate and fast, or do they require practice?

When obstacles are met, what amount of action do they call for and with how many people?

Do we cooperate with others, or are they the obstacle?

Do our actions in the game have agency to affect some larger narrative of the game world, or is the current session self-contained?

What are the rules for discouraging bad behavior?

Based on these factors alone, we can already see how design concepts for multiplayer worlds are generated. By entering design with a purpose, we can begin to build our worlds around how we want players within to interact with one another.

Tabletop designer Jason Morningstar further addresses the emergence of multiplayer games in his East Coast Game Conference 2013 talk, “Tabletop Design Principles.”4 Morningstar argues that rules in a game are just a small piece of the overall social system of multiplayer tabletop games. They “inspire as much as they constrain” players, merely facilitating and focusing interactions that players may have had anyway based on their personalities. Morningstar calls the interactions that occur between the explicit rules of the game and the personalities of individual players the “fruitful void.”

Morningstar’s approach is much like the “experience is key” approach that we have been taking with level design. Apart from a core mechanic, there is also a core shared experience driving the design of multiplayer gamespaces. If one takes the core mechanics or genre of his or her multiplayer game—a shooter, MMORPG, persistent virtual world, etc.—and asks the questions above of it, he or she can find a set of guidelines for designing his or her world. VandenBerghe’s player personality elements allow us to out ourselves in the shoes of different types of players. For example, we might be tasked with creating a first-person shooter deathmatch level for multiple players. What sort of player would that cater to? On the VandenBerghe chart, let us say that the player prefers realism/exploration in the novelty quadrant, not work/skilled5 in the challenge quadrant, mechanics/player vs. player (PvP) for the harmony quadrant, and thrill/multiplayer in the stimulation quadrant (Figure 9.1). Now that we have a theoretical player or player type, we should create a map that can best support this type of gameplay. Let us ask ourselves the domains of play-based questions from above to envision our multiplayer first-person shooter (FPS) deathmatch map:

How many interesting things are there to see? There can be interesting things, but players often will not look at them for very long.

Are challenges immediate and fast, or do they require practice? Challenges are immediate, as players will be quickly shooting at one another. Practice occurs over many matches.

When obstacles are met, what amount of action do they call for and with how many people? Assuming even skill levels, the player with the better firing position or better gun will win.

Do we cooperate with others, or are they the obstacle? In deathmatch every other player is an enemy.

Do our actions in the game have agency to affect some larger narrative of the game world, or is the current session self-contained? Sessions are self-contained.

What are the rules for discouraging bad behavior? Players can be banned from games.

FIGURE 9.1 The VandenBerghe chart mapping for a theoretical FPS deathmatch player. Designing a map for such a player can give us insight into what kind of experience we can create with our levels.

Though not a very technical process, we already have insight into what kind of map to create. The map does not have to have a lot of interesting scenery or embedded narrative, but it should be navigable. Players should not take very long to get to one another, and there should be nodes that channel player activity and allow for large battles. Perhaps some sort of interesting scenery or brighter lighting can be employed in the node areas. The level should have multiple floors so players can gain a prospect-refuge advantage over one another. Lastly, there should be few other obstacles in the level, as the game should focus player attention on one another6 (Figure 9.2).

From our initial ideas, we can go through the steps outlined in Chapter 2, “Tools and Techniques for Level Design,” including whiteblocking and playtesting with the target audience. The hope is that by designing for the right kind of experience and right kind of player, the level will be a success by meeting its design goals.

FIGURE 9.2 Sketches of a theoretical level based on the criteria derived from comparing our genre/mechanics (FPS deathmatch) to our player type from Figure 9.1, and finally our questions based on the five domains of play.

As this example has shown, player personalities and gameplay goals can show us a lot about what kind of map to create. If we keep our eyes on creating a quality experience, our level designs can bring players to the fruitful void of memorable gameplay moments. This technique can be applied to many different types of gameplay and many different types of players as well, giving us a strong starting point for many multiplayer levels. In the next section, we explore precedents for facilitating social interactions in urban design and learn what a hotly contested debate over how cities are arranged can teach us about constructing game levels.

Cities are always the physical manifestation of the big forces at play: economic forces, social forces, environmental forces.

The thing that attracts us to the city is the chance encounter, it’s the knowledge that you’ll be able to start “here” and end up “there” and go “back there,” but that something unexpected will happen along the way.

—QUOTES FROM THE DOCUMENTARY FILM URBANIZED,

DIRECTED BY GARY HUSTWIT7

In many ways, cities are the ultimate emergent system: a collection of thousands, if not millions, of people brought together in a space. As the 2011 documentary film Urbanized highlights, cities are created and changed by, for, and sometimes even in spite of the wishes of inhabitants. Indeed, the destinies of cities are shaped by citizens, special interest groups, government officials, regulations, and economic and social forces. Due to these factors, studying cities, their design, and the history of urbanism can be helpful for game designers in understanding how space facilitates social interaction and gives players agency over the conditions of multiplayer gamespaces.

As we saw in our explorations of Kevin Lynch’s urban design principles, cities utilize discreet elements—landmarks, paths, nodes, edges, and districts—to facilitate movement within. When considering the people part of this environment, Lynch’s spatial rules also seem to aid human interaction: people gather around landmarks or run into one another on the paths between them, districts support different types of activity, etc. Perhaps more importantly, neighborhoods bring a sense of home and belonging. They also produce interpersonal relationships that make people feel safe from some of the negative emergent effects of cities: crime, vandalism, and violence. Allowing for the organic mixing of human activities allows such neighborhoods or opportunities for interaction to occur. The history of urban design has even shown us examples of what happens when cities are not planned for facilitating positive interactions of residents.

Modernism and Non-Emergent Cities

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the city was in a state of flux. Industrialization had packed people into cities looking for work, and cities had therefore become overcrowded. Rich landowners reacted to this demand for housing near industrial sites by packing as many people as possible into tenements for high rents. The result was urban slums like those lamented in the work of Charles Dickens and other nineteenth-century writers.

It was in 1898 that urbanist Ebenezer Howard proposed the garden city plan in his book Garden Cities of To-Morrow.8 Howard’s plan divided the city into concentric circle districts, which separated the functions of cities, living, working, gathering, moving, etc., from one another (Figure 9.3). The vision of this city was that work could be carried out in manufacturing districts, while housing could be placed among wide country green spaces where rent could be kept low. Travel between districts and between interlinked garden cities would occur on large boulevards moving out from the center of the rings.

FIGURE 9.3 A sketch reproduction of Ebenezer Howard’s garden city plan diagrams from 1898. Each ring of the city houses a separate functional district.

The garden city movement had a great impact on modern architecture. In particular, Franco-Swiss architect Le Corbusier evangelized the idea of cities where the functions of living were separated. In 1922 he conceived Ville Contemporaine (Figure 9.4), a city plan where inhabitants would live and work within skyscrapers located in the center of the city. Surrounding the skyscrapers were parks and large motorways, which were themselves surrounded by administrative buildings and universities.9 With Ville Contemporaine, Le Corbusier sought to create the city as a large garden and usher in an age focused on the car and airplane as common transportation types. He saw architecture and urban design as tools for social change and, along with Gerrit Rietveld, Karl Moser, and a number of other famous architects, founded the Congres International d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) in 1928.10 This group was responsible not only for formalizing the rules of what is considered to be the modern style of architecture, but also for promoting architecture as a tool for social and political change. Like Le Corbusier, they advocated for urban design to separate the functions of a city into discrete districts; architect Ellen Dunham Jones has described this as being “like modern graphic design” in the tendency to neatly arrange things.11

FIGURE 9.4 A plan sketch of Ville Contemporaine, a theoretical city designed by Le Corbusier in 1922. The functions of the city are separated from one another, and transit is done by car and airplane.

CIAM disbanded in 1959, but its influence on modern architecture was widely felt. While mainly theoretical, several cities were designed by either CIAM architects or architects influenced by their ideas. Le Corbusier himself designed the plan for Chandigarh, India, as the first planned city after India’s independence in 1947.12 Like many of Le Corbusier’s theoretical plans, Chandigarh separated different functions into their own districts, with blocks for parkland, industrial areas, and government facilities. Initially, the city was largely empty, though today that has mostly turned around. Even recently, however, visitors have commented that the city is sparsely populated with pedestrians.13 Attractions such as Le Corbusier’s Open Hand statue have had difficulty attracting visitors, but this is felt to be mainly due to government restrictions on visiting these sites.14

Another separated-use city, Brasilia, Brazil, makes a somewhat more damning case against Modernist urban planning principles. The city has been described as “beautiful from an airplane, but a complete disaster on foot.”15 Designed by Lucio Costa, the city separates living, working, and administrative facilities among large super-blocks connected with highways. Between are vast green spaces designed to automotive scale. As a result, there are few opportunities for interaction between residents.16

Perhaps the most often cited case against Modernist-inspired urban design is the Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis, Missouri. Completed in 1954 and designed by Minoru Yamasaki, the complex consisted of thirty-three apartment buildings separated by streets and large green lawns. Pruitt-Igoe was originally planned as a publicly owned housing complex in which maintenance money would be generated from rent revenue from the low- and lower-middle-class residents. When new suburban communities enticed middle- and lower-middle-class citizens to leave the city, Pruitt-Igoe was left with only the poorest tenants, and therefore with little opportunity for maintenance income.17 The decay of the buildings was soon met with decreases in resident population and increases in crime rate. In 1972, demolition on the largely abandoned complex began, which was completed in 1976.18 Detractors of Modernist planning cited Pruitt-Igoe’s design philosophy—isolating the function of living from the rest of the city in favor of having large lawn spaces—as being a major factor in its downfall. Novelist Tom Wolfe commented:

On each floor there were covered walkways, in keeping with Corbu’s idea of “streets in the air.” Since there was no other place in the project in which to sin in public, whatever might ordinarily have taken place in bars, brothels, social clubs … now took place in the streets in the air.19

These examples highlight what happens when interactive elements of space are separated from one another or have large areas of empty space between them. In cities, this can lead to isolation of residents and/or crime. In gamespaces, this has the potential to similarly isolate players from one another or make transitioning between two areas designed for different gameplay styles. While some isolation of the gameplay mechanics in an FPS map is helpful, could you imagine a map where areas for spawning or receiving ammunition are far enough away to make gameplay a chore? Could you imagine an online world where you go to one town to buy armor, another to buy potions, and yet another to receive quests?

A lack of tightly defined mechanics for interaction can lead to antisocial behavior. In the early days of the Ultima series, Richard Garriott struggled with how to give players role-playing freedom while encouraging them to behave in socially positive ways within his worlds. For the single-player experience of Ultima IV,20 this led to the game’s theme of becoming a virtuous avatar. An encounter with a player in the wilderness who was enacting the role of a thief a bit too well inspired Garriott to create the reputation system for Ultima Online, which kept violent players out of cities and allowed players to police themselves.21,22

While these problems with separated interaction and the behavior of players in online worlds seem bleak, Garriott’s solutions for mitigating his game’s issues through player enforcement resemble urban design principles advocated by a prominent American writer, mother, and advocate for neighborhood preservation.

Jane Jacobs and Mixed-Use Emergent Neighborhoods

In New York City after the Great Depression, a powerful influence on rebuilding the city’s broken infrastructure was Robert Moses, an urban planner often called the master builder of New York. Moses was responsible for commissioning many large highways and bridge projects that ran through the city. These structures were responsible for breaking up several neighborhoods and leaving residents isolated from one another. He was also an opponent of public transit and tunnel projects, often opting for bridges and parkways even when other options were less disruptive to surrounding areas of the city.

One of Moses’ strongest opponents was Jane Jacobs, a writer who had lived in Greenwich Village since 1935. In the 1950s, Jacobs began writing for the magazine Architectural Forum, focusing on urban development stories. Following a trip to Philadelphia to cover developer Edmund Bacon and his urban design initiatives, Jacobs began to question contemporary urban design practices. She noted that Bacon’s plans focused more on high-rise development on sites than the people’s ability to use them, which contradicted her own urbanistic ideas: focusing on intimate neighborhoods and interactions between residents. In a lecture she would later give at Harvard University, she said, “Respect—in the deepest sense—strips of chaos that have a weird wisdom of their own not yet encompassed in our concept of urban order.”23

Jacobs had become a major advocate for neighborhoods once her comments were published in Architectural Forum. In the late 1950s she successfully fought against Robert Moses’ plans to create an expressway through Greenwich Village. Her struggles with Moses continued over the course of the next decade whenever his plans resurfaced. Jacobs’ most influential work in the field of urban design is the book The Death and Life of Great American Cities,24 which outlines Jacobs’ own disgust with contemporary urban design principles focused on separated uses and large-scale development. The book instead advocates for preservation of intimate neighborhoods and social spaces.

Key to Jacobs’ arguments are her four generators of diversity in cities:

1. Multiuse districts that encourage constant use by people

2. Short blocks to allow easy access to amenities and exploration

3. Buildings of varying age so as to vary economic factors

4. Density of population25

Jacobs’ four generators can greatly influence how we design multiplayer gamespaces to best emphasize the emergence created by the interaction of multiple users. Jacobs uses the term social capital, arguing that the socialization that occurs between individuals in a space can yield both social and economic benefits.26 She cites how a density of people in public places reinforces its safety and develops relationships between users, if only in passing. Eventually, Jacobs’ arguments and those of other user-focused urbanists such as Kevin Lynch would become vital to the New Urbanism movement, which emphasized walkable neighborhoods and multiuse districts.

Using our level design vernacular developed throughout this book, it is possible to say that Jacobs’ views are well aligned with game designers’ seeking of emergent gameplay in multiplayer gamespaces. With a strong focus on planning for the sake of human users, Jacobs’ outlook on design can be of great influence for designers of multiplayer spaces.

Integrating Urban Design into Multiplayer Gamespace

Level designers can take both the failures of Modernist urban design and the influences of new Modernism into account when addressing how players may use multiplayer gamespaces. Modeling multiplayer space design principles on Jacobs’ own diversity generators and avoiding the pitfalls of Modernist use separations, it is possible to create four generators of emergence in multiplayer gamespaces:

1. Multiuse gamespaces that give players access to a variety of mechanics (shopping, talking, fighting, recharging, etc.)

2. Close proximity of functional spaces to one another

3. Spaces for players of different styles, types, or factions

4. Accommodation of player density

To use multiplayer FPS games as an example once again, we may look at how one would model a capture-the-flag level under these principles. Capture-the-flag games divide players into two different teams, often red and blue, who compete to capture enemy flags and bring them back to their own base. Maps for this style of game are often symmetrical, with each team having a similar base on a far end of the map on either side of a wide prospect-scaled battle space. The Valhalla map from Halo 327 is an excellent example of this style, with two bases on either end of a large gulch, featuring intermittent rocks and cliffs for both cover and sniping (Figure 9.5).

Capture-the-flag maps are good examples of how to integrate our four generators into multiplayer worlds. Their rules necessitate certain gameplay styles: defensive shooting by players guarding their team’s flag, offensive raiding for those attempting to capture the enemy flag, and runs from one base to another when the flag has been captured. These requirements also create opportunities for unique gameplay—some players will prefer to hide and snipe into the space between the two bases, and others will take direct paths, fighting opponents head on. Diagrams of the Valhalla map, as shown in Figure 9.6, demonstrate our principles in this fashion. Both bases offer multileveled walkways rather than a direct path to the flag. Flags are cloistered on the bottom level of each base, allowing defensive players the choice to take refuge inside or snipe from upper levels that look out into the gulch. These bases also offer a variety of weapons for players to use: rifles, explosives, etc.

FIGURE 9.5 A plan view of the Valhalla map from Halo 3. This map demonstrates the typical structure of a capture-the-flag map: two symmetrically laid out team bases on either side of a large prospect-scaled battle space.

The gulch between the two bases is also multiuse: players can use the tops of cliffs as sniping positions, or sneak between bases or into cover in the river at the bottom. A turret midway through the map offers players the option of gaining a strategic advantage over the other team, and becomes an important landmark for either attacking or defending forces when flags are being transported between bases. While the map as a whole is large, it does not take much time to traverse, so raids can be quick and battle is nearly constant. This largeness offers additional opportunities for the vehicle-based play that is part of the Halo franchise, and accommodates the many players that may be in one match. All of this combines to create exceptionally emergent styles of play.

FIGURE 9.6 Diagrams of the Valhalla map show how the design of individual components supports emergent gameplay: bases offer different types of weapons and encourage different defensive styles. Terrain changes in the prospect battlefield allow sniping, vehicle, stealthy, turret, or direct styles of combat.

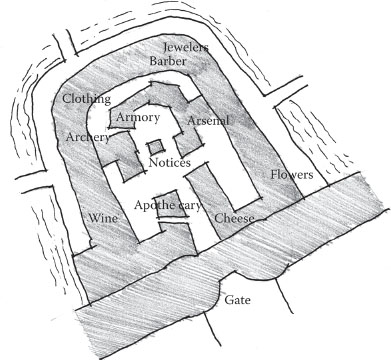

Towns and cities in massively multiplayer online games such as World of Warcraft (WoW)28 also promote emergent social gameplay. In WoW, towns often contain several gameplay-related amenities such as vendors, places to purchase items, and trainers, non-player characters that help players learn new skills. These may be located on the way to larger settlements or to raiding locations—zones where players and their teams fight game-controlled environmental hazards and foes. Likewise, cities contain many of the amenities of towns, but offer even more gameplay-related functions to further encourage social interaction: inns for rest, taverns for socializing, auction houses for exchanging goods with other players, and banks for storing items. Cities may also feature gathering spaces for specific guilds, organized groups of player characters.

These gamespaces are very much organized under New Urbanist principles and therefore fit into our own gameplay-centered generators for emergence. They feature a mixture of use types that are important for a user’s gameplay in WoW: training, shopping, socializing, and facilitating quests. The proximity of spaces to one another encourages a constant presence of players traveling between landmarks, and the diversity of vendors or trainers in any given town encourages the mingling of players of different classes and professions (Figure 9.7). In terms of construction, the shops of vendors or trainers within in-game urban spaces utilize consistent symbolic assets: building types and signage. In this way, players of each class can form a language in which symbols are important to them, and seek out these symbols. When buildings of different types intermingle, emergent socialization is not far away.

FIGURE 9.7 Urban areas in MMOs such as the Stormwind City’s Trade District in World of Warcraft offer a multitude of gameplay activities for different types of players within a small proximity, allowing for social interaction to occur.

The design and the types of functions contained within a multiplayer gamespace help encourage the mingling of different types of players when they follow New Urbanist ideas of multiuse development. While separating uses to focus on singular mechanics may create interesting single-player experiences, multiplayer maps are made more meaningful when they accommodate different types of players. In many ways, the spaces from which players first encounter a gamespace have a lot to do with how they prepare themselves for multiplayer emergence. In the next section, we explore these gamespaces—spawn points and quest hubs—more thoroughly to see how they send players off on the path toward emergent experiences.

THE IMPORTANCE OF SPAWN POINTS AND QUEST HUBS

Throughout the book, we have discussed the importance of pacing on games, alternating high and low action to create manageable gameplay and highlight exciting moments. While many multiplayer games avoid the quiet moments common in single-player experiences, the opportunity to refresh oneself is still a vital part of the experience. In this way, the places in which players appear on multiplayer maps, known as spawn points, and the places from which players embark on missions, which we will call quest hubs, are of great importance.

In previous explorations of emergent gameplay and possibility spaces, we discussed how games such as Minecraft29 introduce players to the possible mechanics of the game through controlled experiences at the game’s opening. As in single-player games, where first levels establish the rules of a world and introduce them to players, the places where players first encounter multiplayer spaces have a great impact on that player’s possible strategies. The possibilities present in spawn points and hubs have a great impact on how players may approach their time in a multiplayer game: What weapons are near them as they spawn? What shops can they access? What are the opportunities for leveling up or improving their skills?

The size of these spaces can greatly affect pacing. In action-oriented multiplayer games such as deathmatch shooter games, spawn points are small and offer a few nearby weapons to get a player moving along—there is no time to linger, only to jump into the game’s action. For players appearing on a map, spawn points are often in defensible places isolated from main action nodes but close enough to them so the spawning player can rejoin the fight quickly, as shown in Figure 9.2 and other similar diagrams throughout the book.

In the cooperative multiplayer shooter game Left 4 Dead,30 players begin each level in safe houses—sheltered areas with extra ammunition and health packs. These spaces are in many ways similar to spawn points in other shooter games, as they allow players to quickly recharge and go if they choose. However, they are largely inaccessible to the computer-controlled zombies in the game, and therefore allow players the opportunity to stay and plan their next moves. In this way, these spaces encourage socialization by letting players plan strategies for moving forward through Left 4 Dead’s gamespace. The game also features weapon and health caches throughout levels, especially before important large-scale battles. These not only control pacing for the game, but also let players decide how they will approach upcoming challenges based on their individual strengths and play styles.

In open-world or MMO games, players have similar opportunities—refreshing or outfitting themselves, socializing, planning, etc.—but within much larger spaces. These spaces, which we are calling quest hubs, have a great influence on how players explore and learn about multiplayer game worlds.

Shaping Player Interaction with Quest Hubs

In many MMOs and online worlds, players often enter the gamespace in a centralized town or designated beginner’s area. In ActiveWorlds,31 a persistent online world, players begin near coordinates 0, 0 on the world map and may move outward from there. Due to the large numbers of players moving through this area, it has become an important in-game commerce hub. WoW players begin in a starting settlement or town dependent on their chosen race. These towns have access to trainers for every class, as well as introductory quests specific to the player’s chosen race. These activities give players a sampling of available character types they may choose and teach them how to play the game. They also facilitate the establishing of unique play styles by giving access to the game’s available classes.

The starting areas in games like WoW work in much slower and more deliberate ways than spawn points in multiplayer action games do. These spaces are larger and meant to be carefully explored. They encourage interaction between players, as they are often laid out with a multitude of things to do and quests to undertake. The multiuser dungeon (MUD) Federation II (Fed II)32 utilizes carefully planned initial encounters with the game world to teach players how the game works and shape their interaction and gameplay. New Fed players are limited to exploring their starting planet until they can purchase a spaceship, which requires gaining a permit and bank loan by utilizing communication commands. This introduces players to some of the basic mechanics of the game and then allows them to venture further once they have mastered these mechanics. Because many of the economic systems that players must contend with to advance are player controlled, the social hierarchy of the world facilitates interaction with other players.

In Quests: Design, Theory, and History in Games and Narratives,33 Jeff Howard discusses quest hubs like those beginning MMOs or MUDs, along with similar spaces in single-player games. These hubs, he says, facilitate outward movement of players from inside hubs out into the larger world map through the use of quests or missions given by NPCs. Many of these missions require players to travel to other towns, which are themselves quest hubs. As such, these games use quests as a method by which to create tours of the game’s possibility space. As players gain more power, movement between hubs and quest selection become easier, giving players more choice over their gameplay experience. Players may also unlock new mechanics as they complete quests.

Federation II’s ranking system is based on this experience of travel, learning, and unlocking new abilities. Each new rank in the game opens opportunities to explore new territories and new game mechanics. For example, after the previously mentioned opening quest to get a spaceship, players must pay off that ship by performing cargo-hauling jobs for the Armstrong Cuthbert Company. These hauling missions act as a tour of the game’s early planets, and also as opportunities for players to visit social hotspots such as bars. Once players have completed the early hauling missions, they may venture further into space, encountering other players. Eventually, as they move up in rank, they unlock access to the game’s other mechanics—stock trading, managing companies, and eventually administrating governments. At this point, players have become the influential characters that newer players will seek out for help.

Enticing Exploration with Side Quests

While emergence is certainly possible if players each have a list of primary quests to take on, more meaningful emergence can only come if players are allowed to customize their travels. For this reason, designers should offer players choices of tasks that are easily findable from their main paths. In many open-world games, the paths between main quests offer opportunities for side quests, tasks or missions that reward players for extra exploration. This type of structure is common in Bethesda Softworks games such as Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, where the game world entices players with views of caves, tombs, towers, and other side quest locations while they travel between major quest hubs (Figure 9.8).

Quest structures in multiplayer RPGs are different than single-player ones, as multiplayer games do not often have a central plot that is advanced by game quests. Some quests or player-defined tasks in multiplayer games may involve more time, players, traveling, and benefit than others. Bigger quests may therefore seem hierarchically more important. Some quests, such as reputation quests in WoW, are smaller repeatable tasks that contribute to a larger-scale goal. Traveling to a bar and buying a round of drinks in Federation II is not a specific quest item, but it may reap social rewards and can therefore be considered a player-defined side quest. Multiplayer gamespaces should offer both large-scale main goals and opportunities for smaller player-defined goals. These give players opportunities to define how they spend their time in these worlds.

FIGURE 9.8 This diagram of Skyrim shows how players are sent from one town to another. Side quests are easily found along the paths between main quest hubs. As such, main quests encourage travel to different parts of the world, within which players may freely access side quest content.

Quest hubs form important nuclei to large game worlds. Players move outward from hubs and into quests and then return to hubs to refresh supplies, gain new weapons, or get new quests. In games that offer guilds, they may also be home bases for players to inhabit with social groups. We next explore the concept of a hometown in a game, and discover the benefit that players receive from having personalized territories.

HOUSES, HOMES, AND HOMETOWNS IN GAMES

While quests hubs act as facilitators of travel throughout games, many players may find themselves favoring specific territories based on their level, their progress through a game’s story, or the social player groups that frequent these locations. Some games take this idea a bit further and allow players to have customizable places that become their own. The previous example of ActiveWorlds allows players to set up their own houses and shops, which helped create the commerce hub surrounding the world’s entry point (Figure 9.9). Second Life34 allows players to craft their own houses and shops and even allows players to sell objects in the game.

The ability of players to customize elements of games gives players additional feelings of agency over the gameplay experience. Customization has been an element of gaming at least as far back as the advent of modern commercial wargaming, which is often attributed to the game Little Wars created by H.G. Wells in 1913.35 These games, such as those in the popular Warhammer36 series, allow players to customize their own figurines with paint and other modifications, even as their stats are determined by common rules. In free-to-play mobile and social games, customization has proven a powerful moneymaking opportunity. In 2011, it was revealed that the economy for hats in the game Team Fortress 2,37 for example, totaled over $50 million.38

FIGURE 9.9 A map diagram of ActiveWorlds when it was known as Alpha World showing the world’s urban sprawl mass as it emanated from the coordinate 0, 0. The area surrounding coordinates 0, 0 became an important commerce hub, as many players passed through there. The ease of remembering coordinates along the game’s x axis (such as coordinates 3, 0), y axis (0, 3), or diagonals (3, 3) allowed these stretches to become similarly valuable as the world sprawled outward.

Beyond the financial benefit to publishers of in-game customization, the ability for players to customize a part of multiplayer gamespaces also has social benefits. Jane Jacobs cites the importance of having a consistent feeling of familiarity with the people in one’s neighborhood. Jacobs argues that the consistent presence of “public characters” such as shopkeepers and other residents helps them protect each other or facilitates introductions between residents who are known to have common interests.39 Having consistent social groups of players is helpful for creating common emergent histories of gameplay events. Clans and guilds can be given the opportunity to meet in in-game social spaces such as towns or taverns. Supplementary spaces ancillary to games, such as chatrooms or forums, likewise allow for the organization of competitions, clans, and rivalries that give multiplayer games meaning.

As mentioned, some game worlds allow players to design and build within them, creating their own home that others may visit. This is useful in games where the primary mechanic is socialization between players, such as Second Life. Second Life allows players to shape the game world themselves. This allows user-created content to be attractions or allows for socialization through visiting one another’s space. This freedom has allowed multiple subcultures to evolve, such as those who use the customizable world for historic reenactments, cultural events, artistic exhibitions, or playing sports.

Animal Crossing: New Leaf40 utilizes the idea of in-game homes to facilitate interaction between players. Players are the mayor of their own town, and may customize it, their player avatar, and their own house as they wish. Social features of the Nintendo 3DS, such as wireless Internet access and StreetPass—a function that allows passing 3DS devices to communicate and exchange data—allow players to visit each other’s towns, exchange items, and give each other gifts. These features allow players to share their in-game achievements and help one another progress through the game by sharing resources.

In this chapter, we have explored how understanding player personalities can inform decisions we make when creating gamespaces for multiplayer games. Focusing on the development of player interactions rather than simply the execution of gameplay mechanics allows for gameplay to enter the fruitful void where interesting and memorable gameplay events occur.

We also explored historic urban design examples to see how the interaction between large groups of people has been managed. We compared Modernist design principles that separated functions and New Urbanist principles that advocate for mixed-use user-focused urban spaces. We saw how the mistakes of the Modernists should not be repeated in our own multiuser game worlds, and how mixed-use gamespaces can facilitate the interaction between players of different skills, styles, and types.

We saw how the structure of the spaces through which players enter multiplayer worlds, spawn points and quest hubs, affect player interaction with the world. Spawn points provide players with a quick opportunity to refresh resources before entering energetic multiplayer battles. Quest hubs encourage exploration, socialization, and introduce gameplay mechanics through carefully crafted introductory quests. These hubs also encourage the exploration of the larger game world, with quests often sending players to other hubs—cities, towns, planets, etc.—thereby giving players tours of the world. These travels also provide players with the opportunity for self-guided interactions and goals.

Lastly, we discussed how the player’s ability to customize his or her own place in these worlds, whether by establishing relationships with specific players or customizing his or her own surroundings, encourages a sense of belonging. These custom in-game “homes” also provide an incentive for socializing in games through visits or gift giving, allowing players to help one another progress in the game.

In Chapter 10, we explore how sound design affects our perceptions of gamespace. Included are explorations of architectural rhythm, ambient sound, and spaces with little or no sound at all.

1. Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, 1961, p. 59.

2. Romero, John. John Romero at BrainyQuote. Famous Quotes at BrainyQuote. http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/j/johnromero483970.html (accessed July 30, 2013).

3. VandenBerghe, Jason. Applying the 5 Domains of Play. Speech at Game Developers Conference from UBM, San Francisco, March 27, 2013.

4. Morningstar, Jason. Tabletop Design Principles. Speech at East Coast Game Conference from IGDA, Raleigh, NC, April 24, 2013.

5. I say “not work” for brevity and because these games provide lots of instant gratification. However, many FPS players work very hard to become more skilled at their games, so in reality FPS deathmatches actually fall somewhere in the middle of not work and work.

6. Technically the final question regards banning for bad behavior, but that is more of an administrative question than a level design one.

7. Urbanized. DVD. Directed by Gary Hustwit. Swiss Dots, 2011.

8. Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, 1961, p. 17.

9. Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, 1961, pp. 21–22.

10. Fazio, Michael W., Marian Moffett, and Lawrence Wodehouse. A World History of Architecture. 2nd ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2008, p. 507.

11. Urbanized. DVD. Directed by Gary Hustwit. Swiss Dots, 2011.

12. Business Portal of India: Investment Opportunities and Incentives: State Level Investment: Chandigarh. Business Portal of India: Government of India, Indian Economy, Investment, Incentives, Trade, Infrastructure, Legal Aspects. http://business.gov.in/investment_incentives/chandigarh.php (accessed August 1, 2013).

13. Morshed, Adnan. Chandigarh. Class lecture, Advanced Architectural Theory. Catholic University of America, Washington, DC, February 7, 2008.

14. Nangia, Ashish. The Town That Corbusier Built. Change Observer: Design Observer. http://changeobserver.designobserver.com/feature/the-town-that-corbusier-built/15028/ (accessed August 1, 2013).

15. Urbanized. DVD. Directed by Gary Hustwit. S.l.: Swiss Dots, 2011.

16. Morshed, Adnan. Brasilia. Class lecture, Advanced Architectural Theory. Catholic University of America, Washington, DC, February 14, 2008.

17. Husock, Howard. The Myths of the Pruitt-Igoe Myth. City Journal. http://www.city-journal.org/2012/bc0217hh.html (accessed August 1, 2013).

18. The Pruitt-Igoe Myth: An Urban History. DVD. Directed by Chad Freidrichs. New York: First Run Features, 2011.

19. Wolfe, Tom. From Bauhaus to Our House. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 1981, pp. 63–64.

20. Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar. Origin Systems (developer), Electronic Arts (publisher), September 16, 1985. PC game.

21. Ultima Online. Origin Systems (developer), Electronic Arts (publisher), September 24, 1997. PC game.

22. Donovan, Tristan. Replay: The History of Video Games. East Sussex, England: Yellow Ant, 2010.

23. Alexiou, Alice Sparberg. Jane Jacobs: Urban Visionary. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2006.

24. Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, 1961.

25. Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, 1961, p. 151.

26. Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, 1961, p. 138.

27. Halo 3. Bungie (developer), Microsoft Game Studios (publisher), September 25, 2007. Xbox 360 game.

28. World of Warcraft. Blizzard Entertainment (developer and publisher), November 23, 2004. PC game.

29. Minecraft. Mojang (developer and publisher), November 18, 2011. PC game.

30. Left 4 Dead. Turtlerock Studios/Valve South (developer), Valve Corporation (publisher), October 2008. PC game.

31. ActiveWorlds. ActiveWorlds (developer and publisher), 1997. Online virtual world.

32. Federation II. IBGames (developer and publisher), 2003. Multi-User Dungeon.

33. Howard, Jeff. Quests: Design, Theory, and History in Games and Narratives. Wellesley, MA: A.K. Peters, 2008, pp. 47–49.

34. Second Life. Linden Research (developer and publisher), June 23, 2003. Online virtual world.

35. History of Wargaming. HMGS. http://www.hmgs.org/history.htm (accessed August 4, 2013). Military strategy games, in reality, date as far back as Wei-qi (known commonly as Go) in 2000 BC, and others. Miniature wargames were also utilized throughout the nineteenth century by armies to practice battle strategies. However, Wells is one of the first to offer the games commercially.

36. Warhammer Fantasy Battle. Games Workshop (developer and publisher), 1983. Tabletop wargame.

37. Team Fortress 2. Valve Corporation (developer and publisher), October 9, 2007. PC game.

38. Good, Owen. Analyst Pegs Team Fortress 2 Hat Economy at $50 Million. Kotaku. kotaku.com/5869042/analyst-pegs-team-fortress-2-hat-economy-at-50-million (accessed August 4, 2013).

39. Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, 1961, p. 68.

40. Animal Crossing: New Leaf. Nintendo EAD Group No. 2 and Monolith Soft (developer), Nintendo (publisher). June 9, 2013. Nintendo 3DS game.