CHAPTER 9

The Sage

Mae loved to knit, but she didn’t like beautiful things. Elegant and chic were two words not in her vocabulary. “If you want something that’s in style, go to a store,” she joked when relatives and friends gave her their requests for tasteful scarves and fashionable hats. Her specialty was tastelessness. Homespun kitsch—the kind of sweaters people wear ironically to ugly sweater parties—those were Mae’s favorite pieces to make. She found beauty in the awful and was determined to share it with everyone she knew.

There was a sweet logic to Mae’s preference for the ugly: in her eyes, the aesthetics of knitting were an afterthought. It was the connections she made with others that she valued most about her favorite pastime. In over 30 years of knitting every day, Mae forgot many of her most hideous creations, but she never forgot any of the people she made them for.

A social worker who constantly went out of her way to help others, Mae made her passion communal. In her living room, she hosted all sorts of friends, acquaintances, friends of friends—anyone with the slightest connection to knitting, from veteran knitters, to eager beginners, to reluctant recipients of future ugly sweaters. At her gatherings, she did what she did best: knitted and talked. While she stitched away, she listened to other people’s problems, offered advice, and helped visitors find other people who might help them solve their problems.

Mae created much more than too many ugly sweaters to count. Her house became a kind of community center where people could chat, meet others, unwind, recharge, find solace, and, of course, knit.

Like a child outgrowing her baby quilt, Mae’s weekly meetings got too large for her house. Eager to keep her at-home community center going, she looked around for other spaces. A nearby elementary school had recently become vacant. She’d heard rumors of an imminent demolition, so she went to the school board and asked if she could rent the space. Mae promised to keep the school in good condition and to pay a fee for the use of the space in return for the creation of an actual community center. The officials thought the idea was great and agreed to let Mae rent the space.

The knitting meet-up was only one of many regular activities at the new center. People of all ages, with interests of all kinds, showed up for a variety of programs, including open counseling groups and courses in painting, crafts, creative writing, and languages. Eventually, Mae let new teachers, mentors, and leaders run the center, and she enjoyed the facility as just another individual.

At the peak of the center’s popularity and success, Mae died. In the wake of her absence—a huge devastation to everyone in the community—the center thrived. Instead of falling apart, the members, who all had different skills and specialties, stepped up and carried on Mae’s legacy. The connoisseur of ugly had left behind a thing of surprising splendor.

A Compassionate

Facilitator

Part connector, part listener, part counselor, Mae is a Sage for the ages, a mentor even to other mentors. In her radiant—indeed, contagious—warmth, she’s a shining example of this most compassionate of creative leaders. Her greatest qualities are the things that define Sages at the top of their games: persistence, empathy, and the desire, above all else, to be around, work with, and learn from both like-minded and totally different people.

Sages are facilitators that put everyone they meet at ease. They attract people and bring them together, creating a family atmosphere and collaborative spirit. Their charisma lies in their reserve, their willingness to let other people speak. Recall the way Mae gladly gave up her role heading up the community center once it got off the ground and she herself became an eager patron. Sages thrive on building a culture—defining the larger character and vision of the people they unite. They are the fundamental source of knowledge for the groups and teams they lead. They are the people who first develop the crucial competences and capabilities that endure for years or even lifetimes.

At the organizational level, the Sage companies are driven by their shared values—often by a desire to help others. They look for input from everyone within and without their ranks, from new and old employees, to consumers, to friends, and they welcome people of all kinds into their family. Think universities. Think Habitat for Humanity. Think Doctors Without Borders. This is a dynastic kind of innovation—a vision that gets passed down from generation to generation.

Example:

A Museum Changes Its Culture

It is precisely this kind of lasting vision that one small Midwestern art museum needed to update as it adapted to a world changing much faster than it was. This is the story of a museum that needed to listen to its Sages. For this museum, innovation was about not merely questioning the rules of the institution but also reimagining the very definition of art itself.

This once-vibrant museum that had played a major role in the cultural and economic life of its community was quickly losing relevance, and its building had fallen into disarray. The directors needed to find a way to both raise money to repair the building and to regain the institution’s artistic reputation.

At the center of this crisis was a large source of money that the museum couldn’t use: a giant trust that had been established by donors in the early nineteenth century, with the stipulation that these funds be used solely for the acquisition of new art. So the current museum directors simply weren’t allowed to tap into the trust to renovate the building or develop new education initiatives. This was a deeply hierarchical institution. Everyone had their own designated responsibilities, which rarely overlapped, and only a very small group of people had a real influence when it came to change.

The museum eventually put together cross-functional innovation teams that paired staff members with local volunteers and community leaders. The jumpstart sessions—mediated by Sages—were energetic and empowering, generating many great ideas.

But when it came to actually carrying out these ideas, the curator—an old bowtie-wearing, Ivy League–educated man—shot everything down. “We can’t do that,” he said to nearly all the plans. The similarly conservative chairman of the board sided with the curator. With this standstill, there wasn’t much they could do.

Then, something curious happened at the other side of the country. The news came out that a well-known, prestigious East Coast historical society was going under. Instead of selling a few of its valuable artifacts, the group chose to shut down its exhibition space and warehouse all its treasures because its directors believed that the central role of a historical society is to preserve art for studying and not to exhibit it to the hoi polloi.

Back in the Midwest, the curator took the position of the historical society directors. He thought that they did the right thing in closing their doors. He, too, thought that fine art was meant to be studied by trained scholars, not appreciated by an uninformed public.

This sparked a vibrant discussion among the museum directors about the fundamental role of art in the world. The deputy director—a younger man (a Sage) committed to making art accessible to as many people as possible—took a meeting with one of the most famous museums on the East Coast. He had the idea to organize a traveling exhibition of his own museum’s collection of the Dutch Masters. It just so happened that this small, underdog museum in the Midwest had one of the world’s top collections of seventeenth-century Dutch painters.

The curator didn’t want to see these paintings on the road. He claimed there was too much risk in protecting these works in transit and that it would cost too much money to insure them. Here was the deputy director’s way in: the giant nineteenth- century trust may not have provided funds for renovating the building, but it did make provisions for exhibitions. So the museum could use that money to insure the paintings.

The traveling exhibit was a major financial and cultural success. Soon, people from all over the globe came to this small Midwestern city to see these world-class masterpieces they couldn’t see anywhere else. With this new income, the museum reestablished its relevance to the community, rebuilding its facilities and launching new education programs for underprivileged children. The Sage-like emphasis on reaching out to new audiences and celebrating the vitality of community is what saved this museum.

The deputy director—the Sage behind this breakthrough innovation—went on to take a position as the head of the major museum association, becoming a kind of cultural hero for small museums everywhere. The traveling exhibition is now a commonplace form of sharing work for a wider viewership and gaining aesthetic and fiscal capital for less-known institutions.

The Old Guard is not your enemy. Here, the curator was not a bad person—he was merely attached to a preexisting set of rules—a sacred cow—that needed to be updated. It wasn’t about antagonizing him. It was about navigating him through the changing world we all shared, communicating with him and others, like a good Sage, and creating a new sense of community (and a new vision behind that community).

Patience:

The Sage’s Greatest Gift and Downfall

The greatest asset of Sages is also their downfall: their patience. The kind of growth Sages seek is very slow. It can even take a generation to develop. In following the long timeline, Sages can miss out on the more immediate opportunities for advancement. It is for this reason that Sages must turn to Athletes as they plan their enduring projects. In this role, Athletes become more like coaches, keeping their team focused on the game that Sages like to forget they’re even playing.

But in their avoidance of the game for the bigger picture, Sages are onto something. The sustainable culture that they work hard to develop—the set of customs and worldview that underlie the way an organization defines itself—is actually what ultimately drives the kind of success that Athletes crave. What Sages show us is that culture creates the economics of innovation.

Innovation Starts with

Mentorship

The key to building culture is the Sage’s go-to mode of expression and connection: mentorship. Culture is about modeling and passing down core ideas and approaches. It involves apprenticing, nurturing, and teaching others. The teaching skills of a Sage are crucial to the success of any organization. For the innovation war room is less like a boardroom and more like a classroom: a place where leaders must perpetually learn new things about the ever-changing landscape of their industries. All innovation initiatives ask us to grapple with what we don’t know now. That’s why, when it comes to growth and creativity, learning is so important—and challenging.

Any Sage call tell you that teaching someone a skill is a lot easier than teaching someone how to apply that skill. Take a quick look at recent book sales, and this immediately becomes clear. This past summer, booksellers reported abysmally low numbers. We spend thirteen years and billions of dollars teaching children how to read, but studies show us that, once they leave school, a quarter of people don’t read a single book in a year. Knowing how to read is not the same thing as wanting to read—or knowing how to apply the information and insights gained from reading.

The other major challenge to learning that Sages know well is one that transcends time and age: whether you’re eight or eighty, a PhD or a GED, if you want to acquire a new skill, you have to go through the failure cycle. We are all novices when it comes to entering the unknown—and we have to be ready and willing to endure early mistakes and missteps.

With new technologies arising faster than we can keep up with and constant changes in the culture of the workforce and customer preferences, it’s not enough to be learners. We need to relearn how we take in and respond to new skills and ideas. We all have to be Sages to ourselves and to those around us.

Learn How

You Learn

It’s time to learn how you learn. Cultivate a self-awareness about your learning process. In the 1960s, Berkeley professors Richard Bandler and John Grinder developed a cognitive inquiry strategy called Neuro-Linguistic Programming that many still use today. The approach claims that there are three types of learning: auditory, visual, and kinesthetic. Howard Gardner, a famous developmental psychologist at Harvard, takes this one step further, insisting that we actually have multiple intelligences: visual- spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, intrapersonal, linguistic, and logical-mathematical. Pay attention to when things make the most sense for you. What is the first thing you do whenever you’re trying to understand a new concept? Do you learn by reading instructions? By watching someone else do it? Or by listening to someone explain it? Knowing your own learning strengths is not just about yourself—it will also help you communicate with others. All effective leaders teach in multiple modalities and realize that one way of explaining something won’t be understood by an entire group.

We need to be sensitive to where people are in their development of a skill. We can’t just jump from the first step to the final step. Bring learners along slowly through each stage. Have acknowledged masters apprentice novices. Masters aren’t always senior leaders. They might be young people who are fluent in new technology or people who have little formal education but have extensive life experience.

Embrace the patience of a Sage and give learning time. All learning is developmental. Speak a foreign language or pick up a musical instrument, and you’ll see that there are no shortcuts. We all need immersion and soak time. Increase your tolerance for failure. Consider the two basic kinds of parents—the ones who say, “Don’t do that,” and the ones who say, “Hurt, didn’t it?” The children of the hovering parents likely won’t learn as much as the ones who have the freedom to do things. The only time we don’t say, “Hurt, didn’t it?” is when the child is in peril. Ask yourself what kind of leader you are: do you let the people around you fail—or are you stopping them from experimenting in the first place? Make learning a team sport.

Pair different kinds of learners together and bring together varying levels—and areas—of expertise. Establish an everyday culture of learning by modeling the learning behaviors you want to see in your team. Show curiosity. Ask questions. Share what you know. Remember that the innovation classroom has no start date and no end date. When it comes to creativity and growth, the Sage knows best: class is always in session.

The Beauty of

Collaborative Innovation

A culture of everyday learning is the new normal. In many ways, the Sage’s perspective dominates our current creative landscape where collaboration and the perpetual drive to learn more reign supreme. Collaboration has recently emerged as the defining characteristic of creativity and growth in nearly all sectors and industries. Today, the biggest breakthroughs happen when networks of self-motivated people with a collective vision join together and share ideas, information, and work.

Collaborative innovation comes in many forms and kinds. From brainstorming sessions like innovation jams to crowdfunding initiatives like Kickstarter or crowdsourcing initiatives like InnoCentive, these forms of growth all mobilize an assorted group of people with a range of skills. The benefits to joint innovation efforts are plenty: the global scale of the initiative, the rapidity of experimentation, the reservoirs of outside talent, and the guaranteed wider array of solutions.

But with each of these upsides also comes a downside: the chaos of implementation, the disruptive power of clients, the difficulty of serving solutions, and the uncertainty of constantly changing course. These are issues that Sages and all teams, at some level, struggle with. The challenge is to achieve equality without uniformity, variety without discord, and cooperation without consensus.

Exercise:

Build a Board of Advisors

In their constant desire for new and diverse voices, Sages are experts at gathering the perfect combination of people with different areas of expertise to provide counsel about important matters. This kind of board of advisors is something that both individual people and large-scale organizations could benefit from. Typically, boards of advisors provide sound advice, help secure resources, and connect you to other high-potential candidates. So it is wise to think like a Sage and continuously develop a manageable board of advisors, typically around seven people. Consider the following points when putting together your board of advisors:

1. To get a comprehensive set of perspectives, be sure to diversify your board of advisors with people from all four dominant worldviews:

• Artists, who explore a wide range of imaginative possibilities and experiment with several of them simultaneously

• Engineers, who review the data and develop detailed plans with sequential steps to resolve their challenges

• Athletes, who eliminate all distractions and unnecessary projects and focus on a few key goals

• Sages, who widen their social circle and discuss their challenges with others to learn if they have solutions that they can use

Deep and diverse domain expertise is essential for a successful board of advisors because it increases our ability to produce constructive conflict and generate innovative solutions. Look for areas of expertise that are relevant to your aspirations. For example, if you intend to create a successful Internet blog, you might want to include someone on your board of advisors who already has a large following.

2. Establish some simple guidelines that encourage positive interactions and esprit de corps.

3. To help secure resources, you need to seek out those influential and powerful individuals whom you know as well as those whom you can come to know through your relationships and networks. Look for people who have shared aspirations and values:

• Who wants the same type of things that you want?

• Who has the means to move you closer to your aspirations?

• What did these individuals seek?

• How can working with you help them get what they seek?

• What is the best way to reach out to them and enlist their support?

Remember, this group of advisors may be engaged at different levels and change over time. Everyone doesn’t contribute in the same way.

4. To enlist and enroll other high-potential candidates into the organization, first consider what others seek and stand to gain by joining in your community. The good news is that everyone wants something. The bad news is that they all want something different: satisfaction, knowledge, connections, prestige, or simply affiliation. Effective networks are complementary. There is something in it for everyone. When you approach potential members to join your board of advisors, consider the offer from their point of view and think of what they want and what you can offer them. Be flexible and work to find a common ground where everyone stands to win from the collaboration.

Once you have formed your initial board of advisors, regularly reach out to them with questions and requests for support and seek out their advice. In return, be supportive to them whenever possible. Encourage the expression of diverse views but work to keep the tension positive. Most of all, work to develop a trusting professional relationship and establish personal rapport. Over time, members of your board of advisors may change as your needs and theirs change.

Keep challenging yourself and those around you to go outside of the limits and boundaries that other people take for granted as fixed or insurmountable. Change up the ways you communicate with others. Pull a Mae and break free of your living room to scope out new locations. Any building has the potential to become the next community center.

Summary

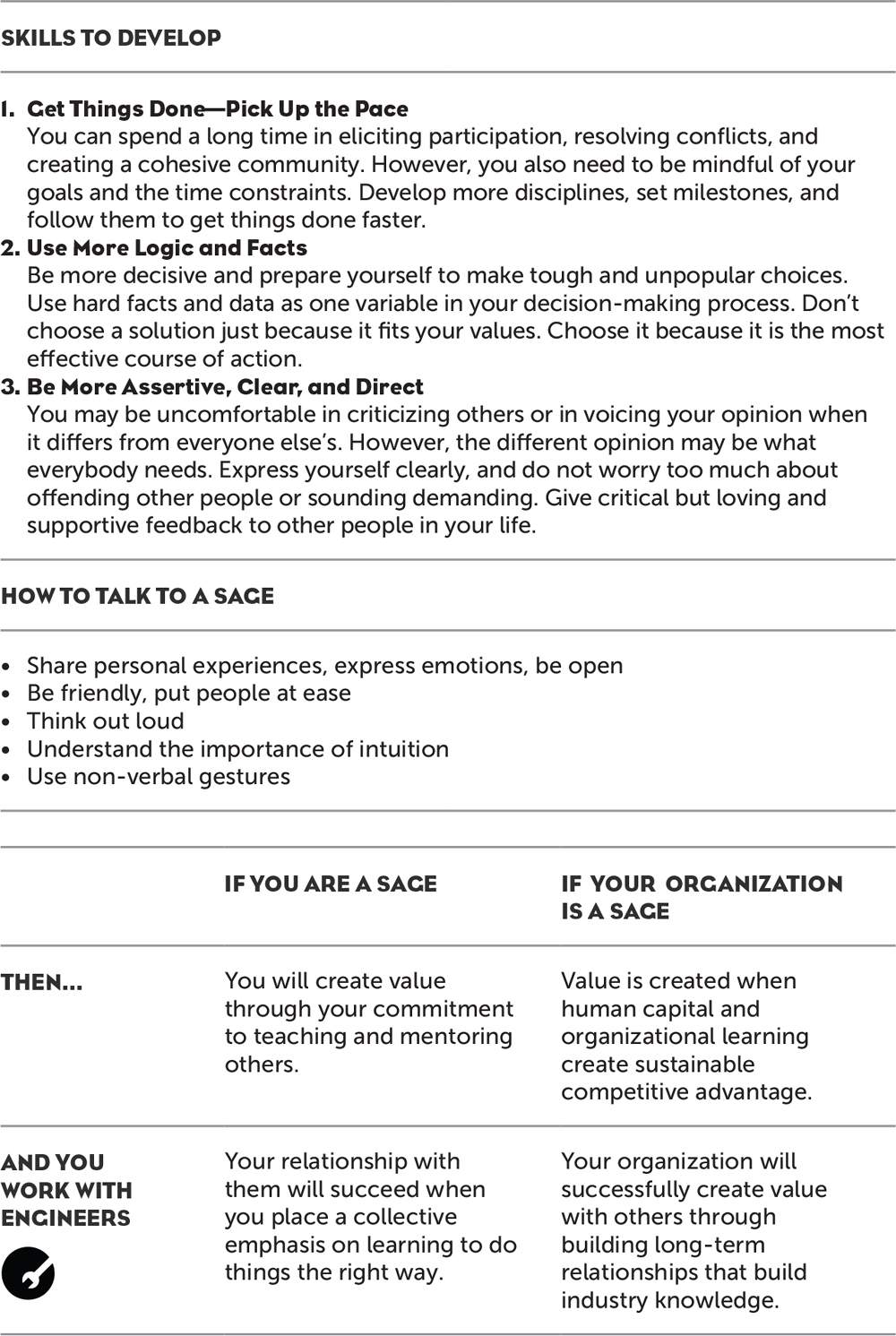

Warm, compassionate, and natural extroverts, Sages love to work in teams and collaborate with other people. They build connections, relationships, and communities. They can grow by learning to assert themselves, avoiding groupthink, and allowing logic to guide their decisions instead of just emotions.