CHAPTER 8

The Athlete

It wasn’t the kids that brought Gary to Kung Fu. When his friends found out he was opening a training studio for students, they were beyond surprised. Gary wasn’t exactly a people person, let alone good with kids. During his time in the military, when he first discovered his passion for Kung Fu, he was a bit of a lone ranger. So, to those who knew him, the thought of Gary surrounded by eager, impressionable kids was unimaginable, comical—even preposterous.

Gary and his students were studies in almost cartoonish contrasts. The kids were in it for the fun while Gary was in it for the ancient Chinese precepts that had drawn him to the martial art as a soldier: the strict adherence to a code of personal conduct and the self-denial. The youngsters who enrolled in Gary’s class were far from the serious, disciplined pupils he expected. They were simply kids brought by their parents, looking for a good time.

Despite his students’ understandably fun-loving spirits, Gary taught the kids the only way he knew how—the same way he had learned martial arts: through systematic repetition, subordination, and self-discipline. The children struggled, cried, and left the program. At first, Gary was disappointed that these kids showed no perseverance and that their parents had enabled this behavior. But when his own children had the same reaction to his training, Gary began to rethink his entire approach.

Gary started with a simple question: How would Kung Fu be improved if it were developed today? He realized he needed to go against all of his usual impulses. He resisted his typical self-sufficiency, impatience, and stubbornness and sought out the help of others to answer this question.

Cold Gary warmed up. He talked with parents who told him that, even though they’d signed their kids up for Kung Fu as a low-stakes hobby, they still wanted their children to develop self-will, respect for others, and the confidence that they could defend themselves if necessary.

Gary also did some research and discovered that soccer, swimming, and dancing were the most popular organized activities with kids. He had a theory that these pastimes created a real sense of belonging and community that children used to get from their church or neighborhood.

If Gary’s friends were shocked when they heard about his plan to teach kids, they were downright stunned when Gary enrolled in some child psychology courses at the local community college. The taskmaster was now a student himself. He supplemented his new education with a wide array of personal achievement audio programs. He developed a deeply insightful point of view about how positive reinforcement was far more effective than some of the traditional methods of martial arts training.

Gradually, Gary began to create an entirely new way to teach the essential ideas and techniques of Kung Fu to kids. He started by enlisting the help of family and friends who had skills wildly different than his own: elementary school teachers, stay-at-home moms, and entertainers, to name a few. He then developed an entire curriculum dependent on the constant positive reinforcement of parents and peers. The tough-as-nails military vet suddenly saw the necessity of frequent awards ceremonies, smaller teams for specific interests, and a lot of “you can do it” attitude and applause.

Soon, the former lone ranger became an unlikely coauthor. One student’s parent was a writer and asked to ghostwrite a workbook about Gary’s method. A local best seller, the book was the beginning of something much bigger: an entire school of thought adopted by others. Now, children and parents were enrolling in the programs in large numbers, and other martial arts instructors were seeking advice from Gary. All the while Gary was growing into a new type of master—compassionate, patient, and perceptive. The only person more surprised than his friends was Gary himself.

The Athlete and the Desire

to Win at All Costs

The aggressive competitor in his perpetual one-man game, Gary is an archetypal Athlete. Peel back the layer of his newfound compassion and patience and you find the qualities that define anyone with this dominant worldview: a cutthroat instinct, the thirst for quick returns, a Darwinist worldview, and the desire to win—often at all costs. All of the things Gary learned not to do as a Kung Fu teacher are the things that make him a successful Athlete.

Athletes are forceful leaders who are driven by profit and speed. They are masters at image-enhancement and deal-making. They thrive in high-pressure environments with quantifiable results. What they seek is power. They reach it by looking at everything that comes their way as a challenge, an opportunity to do something bigger and better than anyone who’s done it before.

At the organizational level, Athletic companies create an atmosphere of winners and losers, where the competitive spirit of laissez-faire capitalism rules. These organizations want strong results, and they want them fast. That’s why they value people based on their output. Think Microsoft. Think Goldman Sachs. Think General Electric. These are companies that will produce revenue under any and all circumstances. It’s not enough for them to be successful—they have to be on top.

In their determined bid for domination bordering on annihilation, Athletes are shortsighted. They win the immediate round but fail to see the long game. Too eager for the instant victory, they don’t have the patience to build the kind of community and culture that sustain durable growth.

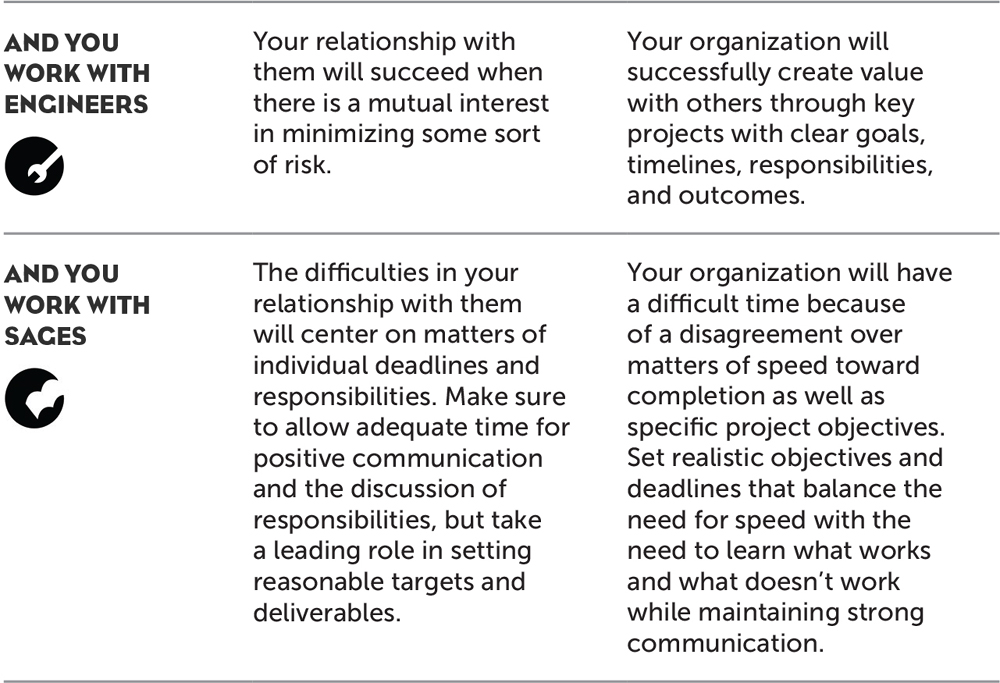

For this reason, every Athlete needs a Sage—a teacher or facilitator who can slow them down and temper their sometimes abrasive concern for the current moment. The Sage brings empathy and interpersonal acuity into the otherwise ruthless boardroom. The killer instinct of an Athlete and the social intelligence of a Sage is a dynamite combination. This is the life-changing insight that made Gary come out on top: he needed the feedback of others to learn what his students actually wanted. With this awareness, Gary won the game that actually mattered—the one that lasted long enough for a whole new generation of martial artists to learn his methods.

Courage

under Fire

We can all use a little Athleticism on our teams when the moment calls for it. The great gift of Athletes is their courage—their willingness to do anything for a win. The remarkability of Athletes’ bravery lies not just in what they’re prepared to do but also in what they’re prepared to sacrifice. It’s the difficulty that innovators often overlook: it’s harder to stop doing something old than it is to start doing something new. The ease with which Athletes give up things that aren’t working is something we should all adopt in our innovation initiatives.

Example:

A News Agency on the Verge of Collapse

Occasional reminiscence is good for the mind and soul, but too much looking backward prevents progress. Excess nostalgia can turn into hoarding—when the past pushes out the future. This is almost always unintentional. There are tons of organizations that inadvertently stifle innovation by fixating on the past, placing too much emphasis on classics and standards.

This was exactly the situation faced by an international news agency close to bankruptcy, in an industry that was changing more quickly than they could keep up with. All the time they spent focusing on their own senior management and maintaining their traditions, they failed to pay attention to the trends emerging in the world around them. The company needed a new start.

It began with the company’s annual meeting. Usually an event held in a sunny tropical place where the organization’s best and brightest could enjoy themselves as they celebrated their successes, the annual meeting this year would be something very different, held at a warehouse in the agency’s home city, in a large open space with no chairs, where everyone would stand as they cultivated an innovative mindset.

The organization created a frenetic, experimental space where individuals from all levels and sectors talked through the five central problems that they collectively diagnosed: the speed at which the organization moved, the adoption of new technology, the development of a twenty-first-century workforce, big data, and client management.

As discussions continued, it became clear that everybody had a very strong desire to win and a determination to make things work. They made plans that they believed would turn things around and put them on top. On the second day, the firm successfully determined precisely what kind of talent it would need to make all of these plans a reality. Everyone took ownership of their responsibilities and made a commitment to each other, spelling out the concrete steps they would take as individuals to contribute to these larger efforts. The energy and desire to win were palpable in the room.

At the end of the summit, one of the organization’s most talented thinkers stood up. He had entered the retreat with huge skepticism and had prepared his official resignation prior to it. In front of everyone, he ripped his resignation into many pieces and threw them all around him. The session had been so promising and encouraging to him that he not only abandoned all plans to resign but also publicly pledged to buy thousands of shares of the company. He sat down and someone else stood up, doubling his pledge. Next, one of the organization’s top leaders vowed to buy triple the shares. The spark of hope spread through the room like a wildfire. It was the Athletic spirit that launched the energy needed to look forward to new fights and new wins.

The end of the story is a happy one, but the year after the retreat was simply awful. Rebuilding the company from the inside out required major downsizing. This meant tons of layoffs and restructuring. In short, the organization had to give up a lot in order to reinvent itself. The next twelve months were painful, yet the outcome was overwhelmingly positive. In the next year, the company saw itself at the top of the industry.

The greatest growth and change don’t happen when executives are comfortably sipping wine in a scenic abbey—it happens when everyone is forced to start over together in an empty warehouse. Innovation hurts. There is no way around this fact: innovation entails tough sacrifices in often drastic circumstances. It’s harder to stop doing old things than it is to start doing new things. The first step of all innovations is destruction. For this reason, innovation takes something much bigger than creativity: courage. What Athletes show us is that, when it comes to innovation, ingenuity and resourcefulness are overrated. Capacity and courage are what will always win the game.

Exercise:

Portfolio Managing

In their ever-impatient search for the next win, Athletes are constantly evaluating what’s in front of them, what’s working, and what’s not working. They look at everything like a portfolio: weighing the advantages and disadvantages of all of the elements in their projects and seeing which makes the most sense to pursue. They know how to weed out projects that aren’t worth their time.

It’s this portfolio way of thinking that is an Athlete’s best asset. Forget what you’ve heard about comparing apples to oranges. It’s often helpful to put your organization’s diverse projects alongside each other and compare them as if they were competing in a race. We can even use this technique to evaluate different things we are doing in our lives. This is the point of maintaining a portfolio: to treat initiatives like investments and to weigh them against each other, balancing and maximizing the relative worth of these projects through disciplined decision-making and resource allocation.

The challenge is that everything in this world costs something. The fact is, most of us want what we don’t possess now but fail to consider what we must give up to get it. It’s not that we can’t have it all. In fact, we can. It’s the cost of having it all that we are unwilling to acknowledge. Our capacity is bound by time and resources. We are all in the perpetual state of being overbooked. This is because it’s easy to start new things. It’s hard to stop old things because they represent our commitments and sense of duty to those we love. It’s not just about us as individuals. We live in families and communities where our changes ultimately become theirs.

The key is to reallocate our resources, time, and energy according to what we really seek now. While stopping the old is the hardest of all the decisions, it is the most important because it makes room for the new. Remember that the world around us greatly enables or inhibits our decisions, so pay attention to which way the proverbial wind is blowing.

When prioritizing, remember that the importance of any task is relative to the other tasks that need to be performed. Think of it like a checkbook. The most important bills get paid first. Use the following steps to rebalance your portfolio:

1. Look at your schedule over a two- or three-week period of time and make a list of all the tasks you currently perform. Now add to that list all the new tasks and projects you intend to start in the near future.

2. Create a table like the one below (Table 5). Use the Y-axis to represent the amount of effort to complete the task and the X-axis for the amount of payoff you expect.

3. Analyze each task in the list and place it in the appropriate cell in the table:

• Big Wins: tasks and commitments that bring great success and are easy to do

• Small Wins: tasks and commitments that bring incremental success and are easy to do

• Special Cases: tasks and commitments that bring great success and are difficult to do

• Time Wasters: tasks and commitments that bring incremental success and are hard to do

Big Wins should always be pursued first because they create the most success for the least amount of effort. Small Wins should be pursued next because they create incremental success and build momentum. Special Cases should be pursued with caution because they typically take far more resources and time than anticipated. There should be no more than one or two of these in the portfolio. Time Wasters should be abandoned, handed off, or dissolved if possible.

Portfolio management requires looking at all possibilities, including the ones that typically fall outside of our own dominant worldview. This requires that we give serious consideration to those initiatives we typically deem less valuable. Constructive conflict is inherent in the prioritization process because the value of each project is relative to the others. This structured decision-making process also allows for us to adjust or re-create our projects into new or hybrid forms. Use the portfolio approach not only to focus on key goals and accelerate their attainment but also to create a balanced portfolio life.

For all the fast, reliable results of portfolio management, there are some downsides. A portfolio sometimes creates too few projects, depends on biased criteria, and encourages myopic thinking. Keep these pitfalls in mind as you make portfolio management work for you.

The Games

around Us

This Darwinist model is what fuels and inspires Athletes. They approach everything they do as if it were a game. It is a worldview we can all benefit from. Conceptualizing innovation projects as high-stakes competitions for the future will not only give your team motivation—it will also give a strategic edge. For the reality is that innovation is a game, and your industry peers are your rivals. So part of the game is realizing that you’re in a game. The organizations that don’t even realize they’re in a competition are always the first losers.

The long-term key to winning is having a strategic edge over your competitors—a playbook that can anticipate the future before everyone else. You can’t actually know the future, but you can feel your way toward it by running many experiments at once and consulting data that can predict what happens in the future. Athletes are expert strategists, which is why they win so often.

But in their unquenchable thirst for instant victory, Athletes miss the larger game. They fail to understand that the game is an end in itself. Sure, all innovations have many finite games built into them, yet there is no real end to the competition.

In James P. Carse’s classic Finite and Infinite Games, he posits that finite games have a definite beginning and ending, clear boundaries and rules, and winners and losers of the contest. In essence, these games are engaging because all of the elements of competition are known, and nothing new needs to be discovered. These are the kinds of games that Athletes crave, the ones where they can rely on their old playbook to win. Recall Gary’s original approach to Kung Fu instruction: repeating the same winning methods that worked for him.

Conversely, infinite games do not have a knowable beginning or ending; they are played with the intent to keep playing, discovering, and learning new things—to keep adding new players to the game. The most winning Athlete is not the one who comes in first every time but the one who reimagines the game itself and becomes more sensitive to the other players. Gary was at the top as a Kung Fu master, yet he didn’t master the teaching of it until he reconceived his approach. And, though his school became a runaway success, he acknowledged that he must remain open-minded to new alternatives and emerging trends. A good Athlete can knock out his opponent. A great Athlete can beat his own record. An exceptional Athlete can adapt to a new game even when the rules aren’t clear. Play on at your own risk. The game’s afoot.

Summary

The Athlete is always competitive, looking to produce the best work possible. Driven and relentless, they plow through barriers. They can grow by learning to be team players and slowing down. Athletes could benefit deeply from making sure that they have support from key stakeholders and considering all the relevant facts before running full tilt.