So the Problem Is…

Why haven’t you been able to draw up to this point? The usual response is that you’re not an artist or that you lack the talent. Actually, if you can’t draw it’s probably because you never truly learned how. Drawing is like reading, a skill learnable by almost everyone. Some people end up loving to read, maybe even writing books, while others can barely get through an e-mail. In each case, the fundamental ability to read is there. The only difference is how much you enjoy (and therefore practice) the task.

To understand why it’s difficult for many people to draw well naturally, we are going to look at how our brains work (or don’t work, in some cases). I’ll share the immediate and practical observations I’ve had while teaching people how to draw. Once you understand how your mind processes the world around you, you can then train yourself to really see your subject and move on to creating accurate, realistic drawings.

The ABCs of Drawing

Let’s continue with the analogy of reading to address some of the fundamentals of drawing. You first learned the alphabet as a series of shapes. You committed to memory the shapes of twenty-six letters (actually, fifty-two when you count both lowercase and uppercase). You memorized the letters and the sounds they made. You might even have learned by placing the alphabet into a song: “AB-C-D …” and so on (although the letter “ellameno” took some time to figure out!). Then you combined the letters to form simple words like cat, dog, run and see.

In drawing, there are really only two kinds of shapes to learn: straight and curved. These simple shapes can be combined to form simple, recognizable images. All of us are able to combine straight and curved lines to create the simplest of drawings.

In reading, you eventually progressed to more and bigger words. With each passing day, you acquired more and more words for your memorized dictionary. Then you strung the words together to form sentences. In art, you might have taken a turn at drawing a more complex critter or car.

Here’s where the natural artists and the rest of the world part. The natural artists develop a few skills to move on and draw more accurately. Everybody else figures there’s no hope and throws down their pencils in disgust.

So what’s the problem then? Why can’t your drawings progress past this most basic stage? Understanding how your mind works can help you overcome this roadblock.

Mastering the Shapes

Learning how to read demanded that you memorize the shapes that made up each letter. Learning the letter R, for example, required you to learn the series of curved and straight shapes that combined to form the letter.

![]()

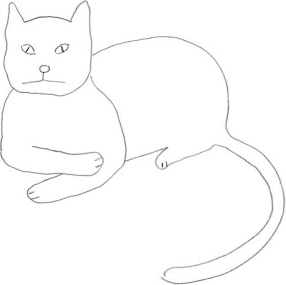

Combining the Shapes

Once you memorized the entire alphabet, you could then combine letters to make words. Likewise in art, you can combine basic straight and curved shapes to form simple drawings like this cat. You’ve gotten this far in your drawing skills already. The goal is to move forward.

Duplicating the Shapes

After a bit of practice, you were able to recognize all letters of the alphabet and the series of curved and straight shapes needed to duplicate or write each letter.

Thinking in Patterns

The human brain is very efficient. It processes information at an astounding rate, then places that information into a memorized pattern so it makes sense to us in the future. For instance, we learn to recognize letters of the alphabet by memorizing their shapes. Once memorized, these shapes are stored in the brain and recalled when necessary. It is this ability to recall information that prevents you from having to relearn the alphabet every time you sit down to read.

The same process applies to objects around us. Your brain records a recognizable pattern for each object and recalls that pattern when necessary. So why doesn’t the object in your drawing look like it does in real life? The answer is simple: When you draw, it is the memorized pattern that you usually reproduce on paper, not the reality of the object in front of you. Anything unique about the object you see may be lost when your brain recalls the pattern on file.

Along with stubbornly adhering to memorized patterns, your brain records only essential visual information, not every single detail. To prove this point, try drawing a one dollar bill without looking at it, and then compare it to the real thing. Notice any differences? Even though you’ve seen the dollar bill countless times, your brain hasn’t recorded the exact details. In fact, you’ve likely only stored enough information to distinguish this piece of currency from any other piece of paper.

This means our mental patterns of most objects we want to draw are missing the details necessary to make the object appear realistic. You may be wondering, then, how veteran artists are able to crank out realistic drawings without even breaking a sweat. This is because our brains continually add shapes and images to our dictionary of patterns. For example, you have learned to read a sentence regardless of the font or handwriting style used. The same happens with drawing: Artists who have been drawing for some time have a large dictionary of patterns that they have been adding to over time. They have probably sketched them many times as well.

So how do you build your dictionary of patterns and ultimately improve your drawings? It’s all about understanding perception, which we’ll talk about next.

The Problem of Primitive Patterns

When we write, we rely on our memorized shapes to communicate. That’s fine for writing but lousy for drawing. Memorized patterns seldom help us create realistic drawings when we’re starting out. This is the case with each of the objects pictured here. Sure you can recognize the objects, but they are a far cry from realistic representations. You must expand your mental dictionary of patterns if you want your drawings to improve.

Understanding Perception

One of my favorite poems explains the role perception plays in our lives. In “The Everlasting Gospel,” William Blake writes:

This life’s five windows of the soul,

Distorts the heavens from pole to pole,

And leads you to believe a lie,

When you see with, not thro’, the eye.

The five windows Blake refers to are the five senses, the means through which we understand and record the world around us. We call this perception, and like Blake suggests, sometimes our perceptions can lead us astray. However, if you have a proper understanding of perception and how it affects your view of the world, and thus your art, you’ll be better equipped to develop strong, solid drawing skills.

A good definition of perception is the process by which people gather, process, organize and understand the world through the five senses. Keeping this definition in mind, there are two important points that every artist should know about perception.

First, each of us has a filter that affects our perceptions. By shaping your filter to meet your interests, you can build upon your dictionary of patterns and develop your artistic skills. However, it can be a challenge to alter your perception without study and practice.

This brings us to the second point—perceptions are powerful. So powerful that they don’t change unless a significant event occurs. In drawing, this significant event is training.

Shaping Your Filter

Perception filters exist solely to keep us from overloading on too much information. If we didn’t have filters in place, we would suffer from sensory overload. As handy as your filter may be in everyday life, it needs to be shaped or altered for you to become a proficient artist.

Training the Eye

As an artist, you must be able to hone your perception of a subject and articulate what you see. Your average dog lover might look at this Great Pyrenees and see a pretty white dog, but a dog show judge or breeder will be able to rattle off the characteristic details that make it “pretty.” You want to be able to see with the eyes of a judge or breeder.

Psssssst!

Psssssst!

When you first begin to draw, your mental dictionary of patterns is limited and untrained, and your perception filter is in full effect. Test your knowledge of the objects around you by drawing them without looking. This exercise results in repetition of known shapes. If you have learned that object accurately, you will be able to reproduce it accurately. If you practice this often enough, eventually your filter will change to allow more details in.

Imagine for a moment that you’re at a dog show and a beautifully groomed Great Pyrenees trots by. If you are an average guy who has a soft spot for animals but who doesn’t possess extensive knowledge of dogs, you might think, “what a pretty white dog.” However, if you are a judge or Great Pyrenees breeder, you might think, “good oblique eye, excellent shoulder layback and level topline.” The judge or breeder has honed his ability to look past the filters and really see all the details of the object he is dealing with—or at least enough detail to know a good Pyrenees when he sees one.

Just as the Pyrenees expert developed accurate perceptions by shaping his filter, you too must alter your filter to really see your object of interest. Becoming a successful artist means training your eye to recognize key information and retaining it in your dictionary of patterns. If you don’t alter your filter, your perception will continue to be shaped by the limited original patterns stored in your brain. Your drawings will never improve until you learn to see all the details that make up your subject.

A Good Reference and a Perceptive Eye

A clear reference photo and the ability to perceive its many details allowed this artist to capture the reality of the cat.

I CAN SEE YOU

Ken MacMillan

Graphite on bristol board

9" x 12" (23cm x 31cm)

Drawing With an Untrained Eye

The average person with no art training will draw a portrait like this one. Even looking at a reference photo won’t help; they’ll still make the same mistakes. For example, the artist of this portrait placed the eyes in the top one-third of the face. In reality, the eyes are typically located about halfway down the face. This fact is clearly provable by looking in any mirror, yet it was missed here. Your perception, fueled by the original patterns stored in your mental dictionary, is so powerful that even the most easily checked data is invisible to you.

Getting It Right

Although I have drawn faces for years, I have to study the face I’m drawing just as diligently every time as I did for my first drawings. I have to make an effort to really take in each individual face that I draw. Easy? Not at all. To make your drawing of a person resemble your source, you should be aware of standard rules of thumb (or patterns) for drawing faces, but you can’t rely entirely on them. Almost every drawing book on faces contains at least one drawing mistake, generally in the size of the iris or the length and width of the nose. In my forensic art career, I’ve had the chance to really study, record and measure faces because I’ve had access to thousands of mug shots in my composite drawing classes. I’ve projected them and measured those thousands of faces, recording the subtle information in the reality of the photos, not the opinions of other drawing books.

You Can Improve—Here’s Proof!

So you’re aware that your filter must be altered to change your perceptions and improve your drawings, but how do you go about doing this? After all, our perceptions are so steadfast that they usually don’t change unless a significant event occurs. Exactly what will it take to get this stubborn ball rolling into motion, then? You guessed it—training. Without training, you will probably be discouraged by your own efforts to learn. Any progress you had hoped to make will be stunted by the frustration of not being able to draw what you see. Don’t worry, help is here! With this book and some practice, you’ll be able to draw anything realistically.

There are four main components to making a good realistic drawing of anything: site, shape, shading and accuracy. You need to know what the parts look like (shape), where they go (site), what the finished product looks like (how to make it real—shading) and how to fix the wobbly parts (accuracy).

After practicing basic pencilling techniques, we’ll work on the four components. By developing each of these skills you will change your perceptions and improve your drawings at a vastly increased rate. I will share every secret I know and hold back no technique that will help you achieve your dreams of becoming a better artist.

I promise it’s possible! Don’t believe me? Check out the before-and-after drawings on the following pages, done by two students from my composite drawing courses.

Before Instruction

In our composite drawing classes as well as our portrait classes, Rick and I begin by explaining about pencils, erasers and paper. We then ask the students to draw a face. These two examples by John Hinds (left) and Greg Bean (right) are average pre-instructional sketches. John was then a detective with the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Department in Everett, Washington. His goal was to draw and he was determined, but he had never drawn anything more advanced than a smiley face. Greg, also a detective with the police department in Bellevue, Washington, enrolled in the class convinced that he would never learn to draw, but he felt it would improve his identification skills.

Psssssst!

Psssssst!

Don’t trash your old drawings! Save them as you go. Embarrassing as they may be, they will help you chart your progress and someday show just how far you’ve come.

After Instruction

John immediately put his newfound drawing skills to work. One of his earlier composites identified the largest serial arsonist in United States history. John retired from the department and was drawing portraits and teaching art within a few years of his first one-week drawing class.

John’s more recent drawing of his wife, Merry Beth, shows how he has learned to let lights and darks create the image. He’s moved away from outlines and developed his own style. He’s simplified some of the shapes and suggested others, focusing the viewer on Merry’s eyes.

MERRY BETH

John Hinds

Graphite on bristol board

10" x 8" (25cm x 20cm)

Psssssst!

Psssssst!

Those who draw the best tend to have the best observational abilities. Thankfully, this is something we can work on rather easily.

After Instruction

Greg seldom let his pencil out of his hands and within a year was advanced enough to help me with a new class. It’s been about five years since Greg took his first class, and the results of his diligent practicing are apparent in his drawings.

JEREMY

Greg Bean

Graphite on 8" × 10" drawing paper

Cheat Sheet

• Drawing is a very learnable skill, much like reading. Both involve the ability to recognize shapes and then combine them for words or drawings.

• Your brain stores limited information about what you see, then recalls these memorized patterns when you try to draw something.

• Beginning artists have a very limited dictionary of memorized patterns.

• Your drawings will greatly improve if you can learn to see objects as they are in reality instead of reproducing a limited pattern from your memory.

• You can expand your mental dictionary of patterns to become a better artist.

• Everyone has a perception filter that limits what we process when we look at something. Otherwise our brains would be overwhelmed with information.

• You will see and draw your subject better if you shape your filter—that is, train your eye to recognize key information and retain it in your dictionary of patterns.

• With solid training (this book!) and frequent practice, anyone can learn to draw well.

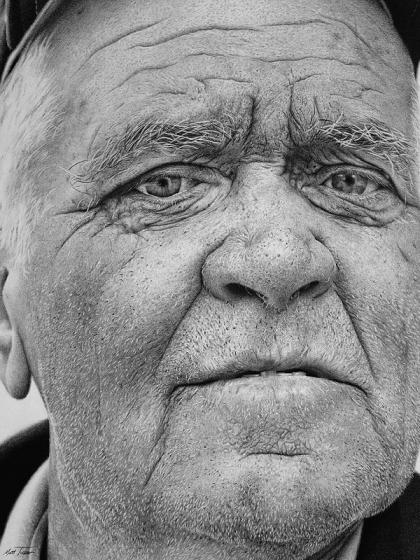

Up Close and Personal

The artist used his pencil in tight strokes to create this highly realistic drawing. The man’s whiskers were erased (or lifted out) and then defined in pencil, a technique you will learn in this chapter.

THE BUM

Matt Tucker

Graphite on 300-lb. (640gsm) cold-pressed

illustration board

21" x 16" (53cm x 41cm)

Collection of the artist