Chapter Two

The Taming of the Muse

“… happy is he whom the Muses love: sweet flows speech from his mouth.”

—Hesiod

When it comes to courting the muse, writers are as superstitious as baseball players. Rituals and icons and talismans abound, all designed to stay on the good side of the muse, who when pleased will let you go with the flow, fire up your imagination, and ward off potential evils, like flat prose and plot holes and writer’s block.

Leo Tolstoy and Friedrich Nietzsche both insisted that the best way to summon the muse is to take a walk. William Burroughs wrote down all his dreams because he believed that his muse visited him while he was asleep. Ken Kesey’s muse was William Faulkner, whom he read to “get going” when he sat down to write.

Some writers beckon the muse with beauty: Amy Tan places historical artifacts related to her work in progress on her desk; Alice Hoffman paints her writing room the color that resonates with her current project. Others rely on particular tools: John Steinbeck used only round pencils—not hexagonal ones—and Elmore Leonard wrote all his novels on legal pads. And, perhaps most famously, many writers lured the muse with liquor: Tennessee Williams said he couldn’t write without wine, and Norman Mailer needed a can of beer “to prime” himself. In fact, so many writers have relied upon plying the muse with booze that alcoholism has often been called “the writer’s disease.”

Then there are the writers who refuse to acknowledge the muse at all. (You know these people—they’re the ones who are always quoting Thomas A. Edison: “Genius is 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration.”) There’s no such thing as inspiration, they’ll tell you. Or if there is, there’s no relying on it. The muse, if she exists at all, is viewed as a fickle creature, as likely to sabotage good work as to bless it.

Even if you don’t believe in the muse, there’s no point in going out of your way to piss her off, just in case you’re wrong. She’s kind of like God in that way.

While you may view all these muse-related rites and remedies as so much nonsense, you can’t deny—Edison aside—that inspired work is work that stirs the hearts of editors, agents, and readers as well. In short, inspired work sells. So let’s take a look at how you can draw on inspiration as you master your craft.

Feeding the Beast

“I learned that you should feel when writing, not like Lord Byron on a mountain top, but like a child stringing beads in kindergarten—happy, absorbed and quietly putting one bead on after another.”

—Brenda Ueland

Woodcrafters know that it’s not enough to build something well—the most successful pieces are beautiful and well built. Form is as important as function.

Marry form and function, and you can create a story that’s as beautiful and well built as a Shaker rocking chair. The Shakers, whose furniture represents perhaps the ultimate expression of form meeting function, considered the construction of each piece an act of prayer inspired by the grace of God.

You may not consider your writing an act of prayer, or call upon the grace of God or the blessing of the muse to inspire you, but if you do, you are honoring the very meaning of the word inspiration, which comes from the Latin inspiratio, meaning “breath of God (or god)” or “divine guidance.”

For best results, however, you need to define your god or muse. An angry, vengeful, Old Testament kind of God or a scolding harpie kind of muse will not serve your work well—and may shut down your creativity completely. What you need is a little fun.

You read that right. Fun. If you are not having fun with your writing, if you find writing torturous and soul killing, then you should do something else. The same is true if you are writing to become rich and famous. There are far less stressful and taxing paths to fame and fortune. If you’re in the writing game to make money, quit now—and take up investment banking. If you’re in the writing game to become a household name, quit now—and pull a Kim Kardashian.

The only reason to be a writer is because (1) you love writing and/or (2) you couldn’t stop writing even if you tried—and you’ve already tried. If the latter applies to you, then you need to learn to enjoy the process. You need to make it fun. It needs to be fun. Or, at the very least, engrossing. That’s what inspiration is all about.

If you’re not engaging yourself, how can you possibly expect to engage the reader? If you’re not amusing yourself, how can you possibly expect to amuse the reader? If you’re not entertaining yourself, how can you possibly expect to entertain the reader?

What’s the most fun you ever had while writing? Be honest. If you’re one of those writers who never has any fun while writing, think again. Sometimes the most enjoyable writing experiences are those that are not part of your career plan. The most fun I’ve had recently while writing was preparing the instructions for a contest at the New England Crime Bake. I was the banquet chair, in charge of entertainment, and given the fact that our guest of honor was the wonderful Craig Johnson, author of the Sheriff Walt Longmire series, I decided that we’d run a (Dead) Cowboy Poetry Contest for all of the mystery writers in attendance. So I wrote up the rules in light verse:

(Dead) Cowboy Poetry Contest Rules

Tonight all you wordslingers

Must earn your own chow.

So sit down with your table posse

For a little powwow.

Pen a (dead) cowboy poem

Worthy of the Wild, Wild West.

(We know you’re really New Englanders,

So just do your best.)

Remember, the cowboy must die

Without losing his boots.

Double score for lingua franca

Like yep, soirée, and cahoots.

A couplet, a sonnet, even

A limerick will do.

And yes, it must rhyme,

Unless you opt for haiku.

In which case Sheriff Longmire

May just arrest you.

You’ve got twenty minutes—

Hell, we’ve killed real men in far less.

So get a move on, little doggies

You’ve got Judge Johnson to impress!

Ridiculous, I know, but I had a great time writing this and was inordinately proud of it—a pride in which I felt justified when the estimable Hallie Ephron called me brilliant. More important, the writing of this silly ditty prompted an afternoon’s solid work on my novel in progress.

Write It Down

Get a pen and some paper, and set the timer for seven minutes. Write about the most fun you ever had while writing. Be honest.

By having some fun first, I tricked my subconscious—the true god of the imagination—into coming out to play. You can do the same thing once you understand the nature of the brain and how to harness it to work for you rather than against you.

Storming Your Brain

“Writing is so much damned fun. I play God. I feel like a kid at Christmas. I make people do what I want, and I change things as I go along.”

—Tom Clancy

Whether you believe that God (or some universal force) took six days or millions of years to create the Earth, you have to admit that, from a storyteller’s point of view, it looks like the guy had a good time doing it. What an imagination: He created an amazing setting with deserts and mountains and swamps and seas and storms and earthquakes and germs and bugs and mammals and Cro-Magnon man, and then he threw in some plot elements like evolution and ice ages. Finally he gave our Homo sapiens hero—or is he the villain?—free will and curiosity and seemingly equal, if conflicting, propensities for generosity and violence. Then he sat back and let the fur fly. Look at the world we live in—this is a world created by a playful God worthy of the act of creation.

Are you a playful God worthy of the act of creation? Playing God is the writer’s job. We all think we’d like to be God—and daydream about what life would be like were we really in charge of the universe. If I were the boss of you and everything else, there’d be no fast food and no parking meters, and there’d be more librarians than lawyers and more poets than politicians and free Wi-Fi and college and yoga for everyone and … . See? That sounds great, until the responsibility of it hits us. What’s to be done about war and world hunger and that wastrel down the street who refuses to clean up his yard?

Deciding who lives and who dies in our stories is just part of that responsibility—a duty that can stop us in our tracks, leading to sleepless nights, unfinished manuscripts, and very expensive therapy sessions. But playing God can also be fun—provided your imagination is fully on board.

The playful god is the one who happily creates entire worlds from scratch, selecting the setting, peopling it with all kinds of characters and creatures, good and bad, and subjecting them all to feast and famine, love and war, death and dinosaurs, and disasters both natural and unnatural. He’s the philologist who designs Middle-earth down to the smallest detail—from the exquisitely intricate cartography to the extravagant cast of dragons, dwarves, hobbits, elves, men, orcs, wizards, and wargs to the numerous complex languages spoken by the aforementioned denizens of his fictive dream (J.R.R. Tolkien). She’s the American scientist from Arizona who imagines a smart and sexy genre-bending historical science-fiction adventure-romance epic about an English ex-combat nurse in postwar northern Britain who is propelled back to eighteenth-century Scotland, where she finds herself caught in the middle of the ongoing skirmishes between the ruling English and the rebellious Highland Scots (Diana Gabaldon).

A Question of Craft

When it comes to playing God, who are your favorite writers? What about their world building excites you? Note: Don’t think only in terms of science fiction writers and historical fiction writers. Think also of Jodi Picoult and her everyday American protagonists in extraordinary circumstances, Carl Hiaasen and his comic take on crime, or Judy Blume and her poignant re-creation of childhood.

Seducing Your Subconscious

“The creation of something new is not accomplished by the intellect but by the play instinct acting from inner necessity. The creative mind plays with the objects it loves. … Without this playing with fantasy, no creative work has ever yet come to birth. The debt we owe to the play of the imagination is incalculable.”

—Carl Jung

As we’ve seen, writers will resort to some interesting and sometimes intense means of inviting the muse to bless their work. Thanks to ongoing developments and discoveries in brain science, we can avail ourselves of certain techniques that can put us in touch with our subconscious mind, the veritable playground of the storytelling gods, home to our intuition, emotions, dreams, memories, the collective unconscious, and more.

I’ve always envied visual artists because they seem to have a direct line to their subconscious. From where I sit as a writer, it looks like they just show up at the studio and plug right into their unconscious minds—and out it pours onto the canvas. Think of Jackson Pollock dribbling and drabbling paint at will, subconsciously re-creating the fractal patterns of nature years before fractals were discovered. I once spent an entire afternoon in front of Pollock’s One: Number 31, 1950 at the Museum of Modern Art, gazing at the work in silent reverence and watching people from all over the world seek it out and gaze along with me.

They say that writing is the most difficult of the arts because it does not appeal directly to a sense. Music appeals directly to our sense of hearing, painting to our sense of sight, the culinary arts to our senses of smell and taste, the textile arts to our sense of touch. When practitioners of these sense-related arts play—Miles Davis jamming on the trumpet, Martha Graham choreographing a dance, Chef Emeril Lagasse “takin’ it up a notch” in the kitchen, Christo and Jeanne-Claude stringing saffron flags from 7,503 gates in New York City’s Central Park—they can count on directly appealing to the senses of their audience in a way writers cannot.

Writing must undergo a translation in the reader’s brain before it can be processed and understood. Typically the writer produces a series of black symbols on a white surface—letters on a page or screen—which must be interpreted by the reader. With any luck, that interpretation corresponds closely to the meaning the writer intended. This extra step puts us writers at a distance from our audience—a distance that other artists do not have to take into account.

All the more reason we should capitalize on our subconscious minds when we write. Here are some techniques that may help you:

- Take a walk. The writers who begin their day’s work with a long walk are too numerous to list here, but you can count Julia Cameron, Henry David Thoreau, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau among them. What’s more, three forty-minute walks a week can actually grow your hippocampus, the part of your brain that forms, stores, and organizes your memories, according to a recent study by the University of Pittsburgh.

- Warm up. You can warm up your writing muscles by entertaining your muse, just as the warm-up band entertains the audience before the concert headliner takes the stage. Try doing a crossword puzzle, writing a letter, or penning a haiku. For me, writing light verse—à la “(Dead) Cowboy Poetry Rules”—works every time.

- Meditate. Meditation enhances creativity—and creativity is your muse at work. Meditate for thirty-five minutes before you sit down to write, and you’ll experience a boost in both divergent thinking (generating new ideas) and convergent thinking (focusing on solving one problem at a time), according to a recent study by Leiden University. Both divergent and convergent thinking are critical to good storytelling. Storytellers who have benefited from meditation include Kurt Vonnegut and Alice Walker.

- Sound it out. Music benefits the brain as well; studies show that listening to music can make you happier, relieve anxiety and depression, and activate the parts of the brain involved in movement, memory, planning, and attention, according to recent studies cited in Trends in Cognitive Science. Charles Bukowski listened to classical music on the radio as he wrote; Hunter Thompson preferred The Rolling Stones. Whatever floats your muse.

- Play it out. If you play an instrument, all the better. Playing an instrument regularly boosts what is called the brain’s executive functioning, which includes problem-solving skills and the ability to focus, say researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital. The most famous writer band—or perhaps the only writer band—is probably the Rock Bottom Remainders, whose members include Stephen King, Amy Tan, Dave Barry, and Mitch Albom.

- Use your hands. Writing by hand boasts cognitive benefits that typing does not, according to a growing number of studies from such venerable institutions as the University of Washington, Indiana University, and Duke University. The finger movements involved in handwriting turn on the parts of the brain related to language, memory, thinking, and idea generation. Many writers always keep legal pads or index cards close at hand, on which they scribble notes for their works in progress. I have a big sketch notebook for each project, in which I jot down notes, draw maps, create family trees, plot out storylines, and paste pictures of characters and houses and whatever else my stories need. I use pens and pencils, colored pencils and magic markers, sticky notes and paper clips. The more toys, the better, as far as your subconscious is concerned.

- Sleep on it. Anticipation can be half the fun. When you’re sleeping, your conscious mind goes dormant, too—but your subconscious mind remains awake. Before you go to sleep, ruminate about your characters, the storyline, those big scenes you’ve yet to write. Get your subconscious excited about your story—and then let it do the work while you get a good night’s rest, just like John Steinbeck liked to do.

Note: For more on writing and your brain, see Fire Up Your Writing Brain by Susan Reynolds.

Three No-Brainer Rules for Your Brain

- Keep it real. The subconscious mind cannot distinguish between reality and visualization. So when you visualize yourself sitting down to write every afternoon at 3 P.M. or pounding out ten pages every night or plotting a thriller with more twists and turns than Hitchcock, your subconscious believes you—so make your visualizations as true to life as possible.

- Keep it simple. Your brain can focus best on only one habit at a time. So if you are focused on summoning the muse—that is, acquiring the creativity habit—don’t try to lose weight or quit smoking or take up running at the same time. Give yourself two weeks to six months to establish your connection with the muse before devoting attention to other habits.

- Keep it positive. The subconscious mind cannot process negation, so be sure that when you sweet-talk your muse, you use positive statements: “I am an imaginative writer,” (rather than “I am not a boring writer”).

I have a dear friend named John whom I’ve known for nearly thirty years. We were reporters for a business paper back in the early days of our writing careers. I gave him his first job in editorial. I didn’t want to hire him. He wasn’t a writer; he worked in what was then known as the paste-up department, laying out the ads for the paper. My boss made me hire him; he liked John. I didn’t—and not only because he wasn’t a skilled writer. He was a green cub reporter, and I was a first-time editor. Neither of us knew what we were doing. He fought me on every edit, was always late with his stories, annoyed the art director at every turn, and never failed to bring out the worst in me. When he challenged me, I was as likely to respond with a raspberry as I was with a civilized remark. (My managerial skills did improve eventually, but not in time for John, my first direct report.)

John’s background was in painting. He’d studied art at the University of Iowa before coming to California. I didn’t know him then, but I’d seen the photos of him—a wild-haired, bearded artist in paint-splattered overalls wielding a brush like a torch—and I’d seen his work—bold, uninhibited, even violent images spilled on the canvas like so much blood. But he seemed to have lost that freedom of expression when he switched from the canvas to the page. He got better at writing, but he tortured himself in the process. He would call me on the phone, having missed another deadline, and say, “I am writhing on the floor in agony.” I would laugh, as he wanted me to do (my laughter granted him another several hours), but I knew that he was dead serious.

John continued to write, and he continued to torture himself. He got better; in fact, he got great. A full-time freelance writer for many years now, he specializes in high-tech reportage and has penned countless articles and columns as well as several nonfiction books. But at heart he’s a fiction writer—one of the most talented storytellers I know. The only problem? He can’t seem to finish any fiction. He wants to—it is his secret life’s wish—but he can’t. Which makes me crazy, because I know I could sell it. More important, I know he could be one of the greats—Stephen King great, Ray Bradbury great, Neil Gaiman great.

But to do that, he’d have to find the fun in it—just as he found the fun in painting as a young man. Enough fun to silence his self-torment.

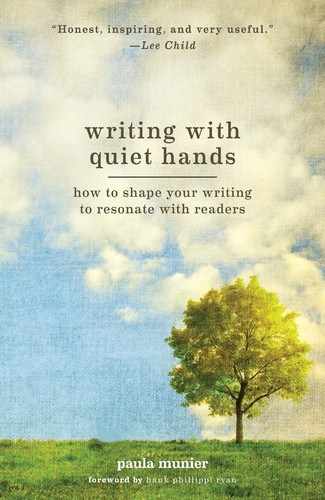

If you are waiting for a happy ending to this story, there isn’t one. At least not yet. But with any luck, John will learn to play again—to write with quiet hands—and readers, myself included, will rejoice.

Inspiration on Demand

“Serious art is born of serious play.”

—Julia Cameron

When I think of a writer at play, I think of Ray Bradbury. I met him once, early in my career, at the Santa Barbara Writers Conference. It was my first real writers conference, and going was a declaration of independence. My friend Susan and I made the trip in her Volvo station wagon, two writers masquerading as suburban homemakers. Susan had quit her job as a reporter for Fairchild Fashion Media when she’d married and had kids. We met at the local park and fell into each other’s company like veterans of a foreign war. We’d spent nearly a year plotting our week-long escape to Santa Barbara. Our expectations were nothing if not high.

Ray Bradbury met those expectations—and more. Bradbury was the Dalai Lama of writers, an enlightened storyteller almost childlike in his enthusiasm for his craft. His joy was contagious; he made you feel good about being a writer and challenged you to enjoy the actual process of writing as much as he did. As he told us—and I took it to heart—“the first thing a writer should be is excited.”

Drill It Down

Think of the last time you read a story in which it was obvious that the writer had a ball writing it. Reread that book, and ask yourself why you think she had such fun. How does her enthusiasm translate to the page? What about the language, the style, the plot, and/or the characters leads you to believe this? Moreover, why did you have so much fun reading it? What have you learned that you can apply to your own writing process?

If you need reminding what excitement looks like, spend some time with children. Any child at play will do, but small children are best—they have not yet had excitement shamed out of them. Think of toddlers digging for wiggling worms in the backyard, kindergartners set loose with finger paints and rolls of blank paper, school-age kids in the sun on the beach building castles and forts out of sand and sea. Even teenagers—out of the grown-ups’ earshot—will drop the adolescent masks of apathy when texting or rapping or hanging out playing video games.

As a writer, it is your mission to recapture that childlike enthusiasm for play. This capacity for play is also a capacity for joy. I’m not saying that every word you write has to be a fun and happy experience—just a playful experience, the mere prospect of which excites you.

Excitement is often made up of equal parts anxiety, anticipation, and, ultimately, exhilaration. Watch a toddler learn to walk: the fearful first steps into the void, the frustration of the inevitable fall, the overwhelming determination to succeed, and, at long last, the unparalleled delight in the final wobbling that marks victory.

The toddler’s path is the path of every creative person. The trick is to rekindle the excitement that fuels the toddler in your writer’s soul. For toddlers, learning to walk is a game they must win. Sure, they could continue to crawl—the safer and more reliable form of travel—but one by one, they pull themselves up and master the art of walking. And then, much to their parents’ trepidation, they win the ultimate boon: They run!

Life for a toddler is one exciting moment after another—serious play that reaps serious rewards. When I was a child, I spent a lot of time with the neighborhood kids playing war. (Before you judge us too harshly, do remember that my neighborhood was an armed camp, as I spent most of my childhood on Army bases, where war was the dominant metaphor of our young lives. We played war the way other kids played hide-and-seek and kick the can.)

I was a good soldier. But, cursed with a short attention span, I would often grow tired of war games and try to convince my pals to play school instead. Of course, I always insisted on being the teacher, which may have explained their reluctance to play along. I liked being the boss, running playtime for me and my playmates—and my commanding play proved good preparation for the writing life.

For when you’re writing, you’re playing, but you’re in command of that play. If you’re writing a thriller, the game could be a suspenseful, terrifying game of cat and mouse. If you’re writing a romance, the game of love could be a dark, tragic tale of unrequited passion—or a boy-meets-girl fable with a meet-cute and a happy ending worthy of Nora Ephron. If you’re writing a family drama, the game could be a domestic war that makes Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? look like child’s play.

Genres at Play in the Films of the World

Television and movies draw directly from the games children play without apology or attribution:

- For every kid who’s played hide-and-seek after dark or dared a pal to spend a long and spooky night in the local cemetery, there’s a horror film based on the same premise.

- For every little girl who’s played out domestic dramas with Barbie and Ken and Midge and Skipper—in which dolls pretend to be girls who make pretend pancakes in pretend kitchens for pretend babies only to end up having pretend affairs and getting pretend divorces—there’s a Doris Day and Rock Hudson movie or a Sex and the City episode or a series like Lena Dunham’s Girls.

- For every boy who’s hung out with his friends, teasing one another and challenging one another to do stupid things, there’s a slapstick comedy featuring the Marx Brothers or the Three Stooges or the guys from The Hangover franchise. (I never liked, nor did I understand, these stories until I had sons of my own. My oldest boy proved incapable of refusing any dare issued by another boy. Suffice it to say that we spent a lot of time in the emergency room and the principal’s office because he was always in trouble for such stunts as jumping off the roofs of buildings and joyriding in school vehicles because a friend as clueless as he was would dare him to do it. Boys being stupid—that’s the basic plot for every bro-mance ever written.)

How have your favorite childhood games—playing with miniature plastic pots and pans, dinosaurs, or action figures; tossing around baseballs or footballs or basketballs with your teammates; dressing up in your mom’s nightgowns, costume jewelry, and high heels—influenced your choice of genre today? Are you sure that you are playing in the right genre?

The Play’s the Thing

Speaking of play, there’s a reason that even dramas as serious as the aforementioned Edward Albee masterpiece Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? are called plays. Think about it: In the theater, plays are comprised of words and actions written by one person and performed on a stage by actors portraying imaginary men and women doing imaginary things in imaginary places in order to entertain the audience. As a storyteller, you do the same thing—only you do it without the benefit of the stage or the actors or the audience. You sit alone in a room making up imaginary people doing imaginary things in imaginary places. That’s playing—whether you enjoy the process or not. So you may as well take a cue from our friend Ray Bradbury and enjoy the hell out of it.

“Inspiration Meets Craft” Equals “Practice Meets Play”

Having fun when you write means rediscovering your sense of play. Look to the games you loved as a child—especially the ones you played when left on your own—for clues on how to develop a playful attitude toward your work.

As an only child, I spent a lot of time alone. Especially in the summer, when we typically moved to a new place—with no school in session and many kids on vacation, I was forced to amuse myself. So I went on a lot of long walks in the woods with my little poodle Rogue, climbed a lot of apple trees, ate a lot of sour apples, and read a lot of books high in the branches, my faithful dog in wait below. I’ve replicated this playtime in my adult writing life. As long as I have apples, books, and a dog by my side, I can usually settle down to write quite happily. When the muse eludes me, I take a long walk in the woods.

Your sense of play is critical to establishing and maintaining a regular writing practice. In order to master your craft, you have to work at it day after day, week after week, month after month, year after year. The paradox here is simply this: To do something well, you have to like doing it enough to devote enough time to do it well—and yet to like doing something, you have to do it well enough to like doing it. Most of us like doing things we’re good at—and eventually we stop doing things we feel we’re not very good at.

Play and practice go hand in hand, just like inspiration and craft. Or at least they should. Dorothy Parker famously said that she hated writing but loved having written—and many writers have joined that chorus since. But let’s remember that she drank to excess.

Better to be one of those writers who loves the writing process—and can’t get enough of it. When it comes to role models, you’re better off choosing Ray Bradbury over Dorothy Parker any day.

And before we move on to how to establish a solid writing practice, let’s give him the last word: “You must stay drunk on writing so reality cannot destroy you.”

Hands On

Remember your favorite games as a child—and play them again. (If you need other people to play them with you, recruit your kids or grandkids. If you don’t have kids or grandkids, borrow some.) What about these play experiences might summon your muse? How might you incorporate these games into your writing practice?