Chapter Eight

The Engine of Narrative Thrust

“That’s the biggest difference between the BookWorld and the RealWorld … when things happen after a randomly pointless event, all that follows is simply unintended consequences, not a coherent narrative thrust that propels the story forward.”

—Jasper Fforde

As a reader, a writer, and an agent, I read thousands of stories a year—or at least the opening pages of thousands of stories. And, all other things being equal, the reason I most often stop reading is a lack of narrative thrust.

Narrative thrust is the taut building of story, beat by beat, scene by scene, chapter by chapter, using the complexities of plot and character to propel the story forward in a dramatic arc that peaks at the climax. You must write each scene so that it leads logically to the next, as if you were connecting a model train, car by car, presenting story questions as you proceed down the track, pushing the action forward to its inevitable, if unpredictable, ending.

Go, Story, Go!

“Sometimes, a novel is like a train: The first chapter is a comfortable seat in an attractive carriage, and the narrative speeds up. But there are other sorts of trains, and other sorts of novels. They rush by in the dark; passengers framed in the lighted windows are smiling and enjoying themselves.”

—Jane Smiley

A lack of narrative thrust occurs when one scene does not logically lead to another. You need to connect each scene, as readers need to know what the protagonist’s motives are, and what he wants in every scene. Only then will they care about what happens next. Otherwise your story will read as a series of random scenes strung together—rather than as a compelling narrative.

Narrative thrust provides momentum for a story; it’s the gas that fuels your story’s engine. You can also think of it as the magnet that pulls the reader through the story. You know it when you experience it—just think of the last story that kept you up all night, the last novel you couldn’t read fast enough and yet didn’t want to end.

But recognizing narrative thrust as a reader and knowing how to create it as a writer are two very different things. In this chapter, we’ll take a look at how you can enhance the narrative thrust of your story—and how you may be unwittingly sabotaging it.

When we talk about novels with narrative thrust, we’re not just talking about the page-turners written by the Gillian Flynns and Harlan Cobens of the thriller world. The best novels in every genre boast a strong narrative thrust. Simply put, this means that the authors have mastered the art of the story question—the who, what, where, when, why, and how questions readers ask themselves as they read, and keep reading.

Much to my family’s annoyance, I’ve been obsessed with story questions since childhood. As a kid, I drove my father crazy asking a million questions as we watched his favorite shows on television. Why doesn’t Matt Dillon shoot first (Gunsmoke)? Is Captain Kirk going to kill all those cute Tribbles (Star Trek)? Can Phelps really train a cat to be a spy (Mission Impossible)? Can I be Joey Heatherton when I grow up (The Dean Martin Show)? The Colonel, not one to appreciate the artistic temperament, would say in an authoritarian voice, “Watch and find out.”

My compulsion to question every beat of a story worsened over time. Once I became a writer and an editor, this obsession became an occupational hazard that always threatened to ruin the viewing pleasure of my nonpublishing friends and family. Yes, I’m the terrible person who leaned toward my companion watching The Sixth Sense just a few minutes into the film and stage-whispered, “But he’s dead, isn’t he?” Even now, decades later, I still drive people crazy by asking questions while we watch a show together. Especially my nonwriter partner, Michael, who, like my father, has a tendency to answer my ubiquitous questions with a sweet if somewhat terse, “Let’s watch and find out, honey.”

If you do this—aloud or silently—as you enjoy a story in any medium, congratulate yourself. Even if your friends and family hate you for it, it’s a good thing. You’re thinking like a writer, putting your writing self in the storyteller’s place and asking yourself, “What would I do if I were writing this story?” Just as important, you’re noticing the story questions in the narrative—and learning by osmosis how you can build them into your own narrative.

Logic and Creativity

Personally, I always get a little annoyed when people assume that since I’m a writer, I’m a flake. That is, a person whose imagination trumps her capacity for logic. This misconception has haunted me since my early days in the book business. When I got my first job in book publishing, I was hired as the managing editor on the production side (as opposed to the acquisitions side). Managing editors are by definition deadline-driven powerhouses known for their common-sense toughness, pragmatism, and attention to detail—logical people, in effect. Several years later, when I wanted to move over to acquisitions, I was told by the publisher that I wasn’t creative enough to be part of that team. Eventually I overcame this perception and became an acquisitions editor, only to be told a decade down the road by another publisher, when I wanted to take on a more managerial role, that I was too creative for such a hard-nosed position.

I tell you this story because it illustrates the black-and-white thinking that prevails even in publishing, by people who should know better. The most successful artists balance imagination with craft, creativity with logic. For a writer, this balance is critical because even the most original story told illogically will fail.

When it comes to this delicate balance, narrative thrust is the canary in the coal mine.

You need to build your original story in a sensible way, pulling your readers along clearly and cleanly with story questions that arise logically from your lucid and precise prose.

A Question of Craft

The next time you watch your favorite television show, risk the enmity of your fellow viewers by verbalizing the story questions that occur to you as you watch. If commercials appear during the show, look for the story questions that arise right before each break.

What Now?

Story questions are posed at the macro, meso, and micro levels—and your job is to build them all into your prose.

The macro story question is the big question that drives the entire plot: Will Cinderella marry her prince? Will Dorothy make it home to Kansas? How will Sherlock Holmes solve the case?

Write It Down

Get a pen and some paper, and set a timer for ten minutes. Consider the macro story question of your own work. Write down possibilities and variations; brainstorm. Now narrow it down to one big question: Will my protagonist find true love/win the war/bring the perpetrator to justice?

Be specific and dramatic. Write down that single macro question, and post it where you can see it as you work on your story. This should help keep your story engine on track.

The meso story questions drive each scene: Will Cinderella’s stepmother let her go to the ball once she’s finished her chores? Will Dorothy survive the cyclone? Will Dr. Watson move into 221B Baker Street with Sherlock Holmes?

And the micro questions are the questions scattered through the narrative at every opportunity—the more the better, as shown below.

Once upon a time there was a gentleman who married, for his second wife [What happened to the first wife?], the proudest and most haughty woman that was ever seen [Why did he marry her? What’s wrong with him? Won’t she make his life a living hell?]. She had, by a former husband, two daughters of her own humour and they were indeed exactly like her in all things [Now there are three of them?]. He had likewise, by his first wife, a young daughter, but of unparalleled goodness and sweetness of temper, which she took from her mother, who was the best creature in the world [Uh, oh, what will happen to that poor child now? Will her stepmother favor her own daughters? Will her stepsiblings be nice to her?].

—from Cinderella by Charles Perrault

The house whirled around two or three times and rose slowly through the air [Where is the house going?]. Dorothy felt as if she were going up in a balloon [What will happen to Dorothy? Will she survive?].

The north and south winds met where the house stood [That can’t be good, right?], and made it the exact center of the cyclone [Is that good or bad?]. In the middle of a cyclone the air is generally still, but the great pressure of the wind on every side of the house raised it up higher and higher, until it was at the very top of the cyclone [How high is high? What will happen when the house falls?]; and there it remained and was carried miles and miles away as easily as you could carry a feather [What about Dorothy and Toto? What’s happening to them? Will they be carried away like feathers, too? When will gravity win out?].

—from The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum

Sherlock Holmes seemed delighted at the idea of sharing his rooms with me [Why would he be delighted when he doesn’t even know Watson yet?]. “I have my eye on a suite in Baker Street,” he said [What’s it like? Is a suite big enough for the two of them? Is Baker Street in a good neighborhood?], “which would suit us down to the ground [Why would it suit them?]. You don’t mind the smell of strong tobacco, I hope?” [Will the good doctor want to share a room with someone who smokes?]

“I always smoke ‘ship’s’ myself,” I answered. [But he’s a doctor? Will they both die of lung cancer?]

“That’s good enough. I generally have chemicals about [What kind of chemicals?], and occasionally do experiments [What kind of experiments?]. Would that annoy you?” [Why wouldn’t it annoy him?]

“By no means.” [Seriously? Is Dr. Watson the most congenial man who ever lived?]

“Let me see—what are my other shortcomings [How many does this guy have?]. I get in the dumps at times [Why?], and don’t open my mouth for days on end [What’s wrong with him? Why would he tell Dr. Watson that?]. You must not think I am sulky when I do that [Why wouldn’t he?]. Just let me alone [How can he leave him alone in what might be small quarters?], and I’ll soon be right [Really? Doesn’t this guy need therapy?]. What have you to confess now? [Why would Dr. Watson confess any shortcomings to a perfect stranger?] It’s just as well for two fellows to know the worst of one another before they begin to live together.” [Is it really? What will Dr. Watson say?]

I laughed at this cross-examination. “I keep a bull pup,” I said, [He’s a guy with a gun?] “and I object to rows because my nerves are shaken [He’s a nervous guy with a gun? Why doesn’t he like to fight?], and I get up at all sorts of ungodly hours [Why can’t he sleep?], and I am extremely lazy [Really? Why would he say that about himself?]. I have another set of vices when I’m well [What’s wrong with him? Does he have PTSD?], but those are the principal ones at present.” [Isn’t that enough? Is their sharing a flat a nightmare waiting to happen?]

—from A Study in Scarlet by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

If you’re thinking, Give me a break, these examples are very old. Times have changed, and the criteria are different now—well, you’re half right. They are old examples and times have changed and the criteria are different—they’re even worse now, at least in terms of story questions. You need to start immediately with compelling story questions and keep ’em coming until The Very End, as these recent blockbusters do from the first word:

“We should start back,” [Why should they start back? What’s wrong? Where are they? Who are they?] Gared urged [Who’s Gared? Who’s he talking to? Is he scared?] as the woods began to grow dark around them [What woods? What comes out when the woods grow dark?]. “The wildlings are dead.” [What are wildlings? Why are they dead? Did Gared kill them?]

—from A Game of Thrones by George R.R. Martin

Though I often looked for one [Look for what? Why bother to look?], I finally had to admit that there could be no cure for Paris [Why Paris? What cure? Who needs a cure for Paris? What happened to her in Paris? Is she still there? Why does she feel compelled to admit this? What does it mean?]. Part of it was the war [Which war? What happened to her in the war? Is the war still raging? Is she in danger? What did Paris have to do with it?]. The world had ended once already [Ended how?] and could again at any moment [Why? What’s going on?].

—from The Paris Wife by Paula McLain

“So now get up.” [Who’s talking to whom? Who needs to get up? Who pushed him down? Or did he fall?]

Felled, dazed, silent, he has fallen [Who has fallen? Is he badly hurt or just scared? If so, of whom? Did he hit his head? Why is he dazed?]; knocked full length on the cobbles of the yard [Cobbles? Yard? Where is he?]. His head turns sideways; his eyes are turned toward the gate [What gate? To or from where?], as if someone might arrive to help him out [Will someone arrive to help him? Who? Does he have no friends? No family?]. One blow, properly placed, could kill him now [Who’s going to kill him? Whoever’s talking to him? Who would want to? Why? What is he going to do? Just lie there and let it happen?].

—from Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel

Did you note all the story questions raised in just a few opening lines? That’s narrative thrust. That’s your competition. That’s what you need to do, too.

Drill It Down

You’ve determined your macro story question. Now it’s time to figure out your meso and micro story questions.

- Go through your scene list (remember your index cards?) and write down the story question for each scene. If you can’t see one, you should rethink that scene; every scene needs a strong story question to drive the action forward.

- Next, go through your story scene by scene, and make sure you’ve peppered your prose with story questions. You need at minimum a solid story question every 50–100 words. More is better.

Scaring Readers Silly

At its heart, the purpose of narrative thrust is to put the fear of the storytelling gods in your readers. Whether you are writing a horror story or a lighthearted romance, you are scaring your readers into turning the pages. Do your job right, and they’ll want to see what happens next; they’ll need to see what happens next. They’ll feel compelled to keep reading, no matter how late the hour or how long the story.

The logical progression of your scenes, as well as the story questions that fuel the action in those scenes, are responsible for scaring your readers silly. But just as important is pacing, the rate of your narrative thrust. Pacing is the gait of your storytelling—and a slow horse is a dead horse.

The very word pacing has become a touchstone in the industry today; if I had a dollar for every editor who complained publicly or privately about the so-called “pacing problems” plaguing today’s submissions, I’d have a lot more dollars—and lot more deals. It’s gotten to the point where many editors will refuse to review manuscripts based solely on word counts they deem too high. The rationale: If the story is that long, it must have “pacing problems.”

To make sure your pacing is on track, here are some dos and don’ts, all of which you ignore at your peril:

- DO make something happen. The biggest issue in most stories is that not enough happens. There’s no narrative thrust without action.

- DO have your protagonist drive that action. The reader wants to identify with the hero, and through him experience the transformative journey that the story takes him on. When the hero is passive or inactive or a bystander to the proceedings, the reader’s interest flags.

- DON’T confuse foreshadowing with forecasting. Foreshadowing is a literary tool by which you use tone and style to create a mood or evoke a feeling, typically of foreboding. This helps create suspense. But when you come right out and tell the reader what (usually) bad thing is going to happen, you’re forecasting—and eliminating any suspense that may otherwise have strengthened your narrative thrust.

- DON’T break the fourth wall. This is often an excuse to tell the reader what’s going to happen before it happens—thereby destroying any suspense you may be trying to build. This is the “If only I had known” device, which is hopelessly old-fashioned and, more often than not, just plain lame. As in: “If only I had known that by the end of the day/night/week/month/year, my career/romance/life would be changed forever.” Again, you’re depriving your readers of the element of surprise. Worse, you’re taking them out of your story to do it.

- DO raise the stakes for your heroine. Give her bigger and bigger obstacles to overcome as your story progresses; make those story questions increasingly challenging.

- DO add a ticking clock if you can. Give your protagonist a hard-stop deadline—if he doesn’t find the bomb by 2 P.M., it goes off; if she doesn’t tell her mother to butt out of her life by Friday, she’ll miss the chance to sail off into the sunset with her beloved on that weekend cruise to Catalina.

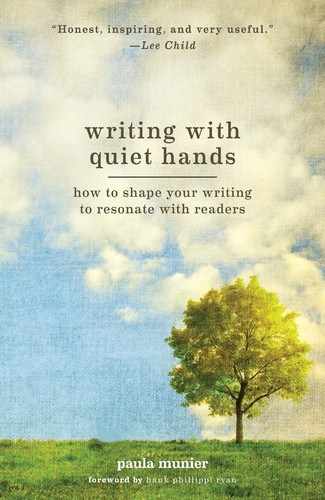

- DO as the king of pacing, Lee Child, says: “Write the slow parts fast and the fast parts slow.”

- DON’T belabor your descriptions. Stick to the one telling detail. Don’t describe your heroine’s every feature; just tell us that she never leaves the house without mascara.

- DON’T let your characters talk too much. Dialogue should not replace action.

- DO aim, above all, for clarity. Whenever readers have to stop to think about what you’re trying to say—or worse, reread it!—you risk losing them forever.

Pacing is the one element of craft I am very particular about as an agent. If the pacing is off, I won’t shop the story. Period.

Hands On

Go through your story with Elmore Leonard’s directive to “leave out the parts readers skip” foremost in your mind. Whenever you even suspect that the narrative thrust is lagging, highlight that section. You’ll need to rework it later (with the help of chapters eleven and twelve). Feeling particularly brave? Ask a forthright (nonwriter) friend who’s a well-read fan of your genre to read your story and mark wherever he feels bored, lost, or annoyed.

“… there is a tradition of strong narrative thrust in English fiction, and all our great novelists of the past have had it.”

—P.D. James