Chapter Sixteen

Wherever You Write, There You Are

“So what will you do today, knowing that you are one of the rarest forms of life to ever walk the earth? How will you carry yourself? What will you do with your hands?”

—Mark Nepo

As I begin to write this last chapter, snow is falling, falling, falling. I look out my living room at the lake behind the cottage, where the record snowfall has drifted in high swells across its wide frozen face. It’s been snowing ceaselessly for two weeks now, and much of Boston is literally snowbound. The trains aren’t running and the roads aren’t plowed and the weatherman says that more snow is on the way.

Even the hardiest New Englanders are growing cranky. Spring is still an endless thirty-nine days away. Nobody can go anywhere—and the few people who try are mostly stuck cursing in their cars on the highway. Cabin fever is setting in; a collective cloud of discontent has descended upon the Commonwealth.

I can’t go anywhere, either, but I don’t care. I have heat and power and the blank page before me. While the rest of my compatriots shovel on, planning trips to Florida and preparing to list their homes for sale and move south come spring, I’m on holiday—an unexpected writer’s retreat, courtesy of Mother Nature. I couldn’t be happier.

This is the glory of being a writer. This is the reward of writing with quiet hands. Faced with enforced solitude, we are content to sit tight and write on.

A Question of Craft

Often the gift of unexpected writing time comes disguised as an inconvenience—bad weather, cancelled plans, a long wait at the DMV. When you are blessed with such a gift, do you see it as a blessing? Do you take advantage of it? Do you sit tight and write on?

(Remember) Why You Write

“Writing is the only thing that when I do it, I don’t feel I should be doing something else.”

—Gloria Steinem

Often the accoutrements of the writing life—the effort to get published, dealing with agents and editors and publishers and booksellers and readers, the obligatory promotion and marketing activities, the pressure to sell, sell, sell books—can interfere with the writing process. To paraphrase E.L. Doctorow, anything that happens to a writer can be bad—failure and success, fame and fortune, obscurity and poverty, praise and pans.

The literary landscape is littered with writers who give up too soon. One of my most-talented clients stopped writing, depressed because her first novel did not sell. I told her to write the next novel and let this one go. This is what I tell all of my clients, but I can’t make them listen. The ones who go on and write the next novel—and the next and the next—get published. Most writers do not sell their first novel. But they sell their second or third or fourth one. They keep writing because they are writers. They don’t let failure stop them; they keep writing with quiet hands.

Once you start putting your work out there, it takes on a life of its own—and you have no control over it. The more you worry about it, or try to manipulate its future, the more miserable you become. And the less new writing you do. Putting your story into the world is like realizing that your children are all grown up and ready to leave home. They need to fly solo. They no longer belong to you. If you’ve done your job right, they know that—and they are free to embark, unfettered, in search of their destiny. And you need to let them go. Otherwise you may never hear from them again—or when you do, it’s against their will. They’ll come back to you when they are good and ready, on their own terms.

The same is true for your work. It no longer belongs to you. It belongs to the readers, however many or few they may be. Just as you may applaud your adult children’s triumphs or bemoan their setbacks, you may applaud and bemoan your work. But you can’t fuss over every bump in the road. And there will be bumps.

Victory can be just as debilitating as defeat. Think of Margaret Mitchell, who was so disconcerted by the overwhelming success of Gone with the Wind that she never wrote another book. Or Harper Lee, who is finally publishing another book after her monumental achievement, To Kill a Mockingbird, silenced her for decades. But this book, Go Set a Watchman, is one she wrote before she wrote the novel that made—and destroyed—her as a writer.

No matter what happens to your stories once they enter the universe of readers, remember why you write. Hold on to your muse. Persist in your writing practice. Continue to master your craft, and take pride and pleasure in your craftsmanship.

Ultimately all that matters is your relationship to your writing self. Do whatever you have to do to keep that relationship happy, healthy, and productive.

Because you’re in this for the long haul.

“For me, writing a novel is like having a dream. Writing a novel lets me intentionally dream while I’m still awake. I can continue yesterday’s dream today, something you can’t normally do in everyday life.”

—Haruki Murakami

Writers with Quiet Hands

When you need a little inspiration or the muse is eluding you or you’re in danger of forgetting why you write, here are the works that can help you remember:

- Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott

- On Writing by Stephen King

- The Book of Awakening by Mark Nepo

- Writing Down the Bones by Natalie Goldberg

- Walden by Henry David Thoreau

- One Writer’s Beginnings by Eudora Welty

- New and Selected Poems, Volume Two by Mary Oliver

- Zen in the Art of Writing by Ray Bradbury

- The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron

- The Writing Life by Annie Dillard

- The Paris Review series

- The New Yorker writer interviews

- Charlie Rose show writer interviews

“People spend a lifetime thinking about how they would really like to live. I asked my friends, and no one seems to know very clearly. To me it’s very clear now. I wish my life could have been like the years when I was writing Love in the Time of Cholera.”

—Gabriel García Márquez

Write It Down

Get a pen and some paper, and set the timer for twenty minutes. Write about what success as a writer means to you. Dream big for your story—and detail which destiny you’d choose for it, if you could. When you are finished, fold up that paper and slip it into the back of your sock drawer—and forget about it.

The Long Haul

“I am large, I contain multitudes.”

—Walt Whitman

When you write with quiet hands, you have the tools you need to be in this writing game for the long haul. Approaching your writing as a craftsperson gives you permission to play. To go big.

Part of surviving and thriving over a lifetime of writing is allowing yourself to grow, to push your own limits, to reach for the stars in your own creator’s universe.

Or, as I like to tell my clients and writing students: Write epic shit.

Go for broke with every book. Tell the story you thought you couldn’t tell—and trust that you’ll develop the craftsmanship you need to tackle that too-big story as you write it. Because you will.

Trust the writing process itself—and you will prosper. Don’t worry about the critics. Don’t let the naysayers win. There’ll always be plenty of people around to tell you that you suck, that your writing sucks, that there’s not a snowball’s chance in hell that you’ll ever make it as a writer. Ignore them. Most of the time they are motivated by jealousy or cynicism or mean-spiritedness that has nothing to do with you. (My mother would give me this advice when I was a little girl and one of my peers hurt my feelings. I never believed her. Then I grew up and became a writer and realized that in this, as in many other things, she was right.)

Once you get published, this criticism will only increase. In fact, they’ll actually pay people to put you and your work down. (They’re called critics.) You’ll need to learn to process any constructive criticism you may receive and delete the rest from your memory banks forever.

I learned this early on in my career, when I was the editor of a business publication in Monterey. I’d written an innocuous profile of a local business, the sort of predictable feature one finds in such weekly newspapers. And yet this story, humble as it was, enraged two readers enough to prompt them to write angry Letters to the Editor. One called me a fascist; the other called me a communist. Both called for my dismissal.

Luckily my publisher believed that if you didn’t provoke at least one reader to write an irate Letter to the Editor every week, you weren’t doing your job. He was inordinately pleased with me. I was relieved—and from that moment forward paid very little attention to most of my critics.

“I cannot greatly care what critics say of my work; if it is good, it will come to the surface in a generation or two and float, and if not, it will sink, having in the meantime provided me with a living, the opportunities of leisure, and a craftsman’s intimate satisfactions.”

—John Updike

Ignoring such attacks can prove difficult. Fail to do so, however, and the barbs can fester, poisoning your will to write and/or publish your work. Sometimes it helps to ritualize the process of letting criticism go. A couple of years after I received those accusatory Letters to the Editor, I was serving as the editor of Santa Cruz County’s alternative weekly newspaper, Good Times. One of my reporters wrote a story that infuriated a reader, who wrote a long, vicious diatribe denouncing the story and its writer. Our policy was to print every Letter to the Editor, whether flattering or unflattering. Everyone on the editorial staff had read the letter. The reporter was embarrassed and humiliated.

I could tell that she was taking the letter’s unfounded accusations and criticisms too much to heart. So I had her make a copy of the original letter. I invited my entire editorial staff, all of whom were upset about the incident, out to the parking lot behind our offices.

“Time for a ritual burning.” I gathered the group into a circle and held up the offensive missive. “We all know that this is crap written by a crank. Let’s give it the reception it deserves.”

Everyone laughed, a little nervously, as no one was quite sure if I was joking or not.

I borrowed a cigarette lighter from one of the smokers in the crowd and handed it, along with the copy of the letter, to the reporter. “Why don’t you do the honors?”

The reporter grinned and set the letter afire. Everyone cheered.

With the criticism literally up in smoke, the reporter continued to write great stories, for that publication as well as many others. Now she’s a published author and, I’m happy to say, my client. As I write this, I’m getting ready to shop her first novel.

Whenever your critics put you down, conduct your own ritual burning. If that’s a little too harsh for you, then do what we do in yoga—and release your critics to their own destinies. Karma, baby—it’s what all unreasonable and unjust critics deserve.

“If you wrote something for which someone sent you a check, if you cashed the check and it didn’t bounce, and if you then paid the light bill with the money, I consider you talented.”

—Stephen King

Drill It Down

According to a study in the Review of General Psychology, people remember criticism far longer than praise. What’s the worst criticism you’ve received as a writer? Was there anything you could learn from it? Does it still haunt you? Write down the worst things anyone’s ever said to you about your writing. Now perform a ritual burning of your own.

You on a Book Cover

“Writing isn’t about making money, getting famous, getting dates, getting laid, or making friends. In the end, it’s about enriching the lives of those who will read your work, and enriching your own life, as well. It’s about getting up, getting well, and getting over. Getting happy, okay? Getting happy.”

—Stephen King

We all dream about getting published. We all picture our stories on the bestseller lists. We all long to be the ones who follow in the footsteps of the great storytellers we love and admire.

How many times have we heard of some churlish action on the part of a rich and famous writer and shaken our heads in dismay: Jonathan Franzen insulting the readers of Oprah’s Book Club, James Frey making up parts of his memoir, Norman Mailer stabbing his wife.

If we were ever lucky enough to be those guys, well, we wouldn’t be those guys.

If we were ever lucky enough to be published, we’d be generous and magnanimous to family and friends and fans alike. We’d be as enthusiastic about our craft and as encouraging to new writers as Ray Bradbury was. We’d give away as much money to good causes as Nora Roberts and Isabel Allende and J.K. Rowling and Jonathan Kellerman and Dean Koontz do. We’d keep stretching our limits and writing through thick and thin, like Joyce Carol Oates and Isaac Asimov. In short, we’d be swell.

Well, now’s the time to prove it. The time to be that writer, the one you promised you would be before you got published. Gracious. Graceful. Grateful.

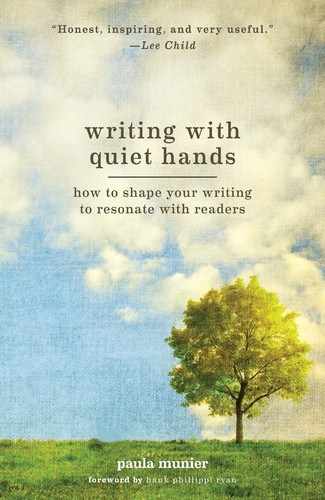

Writing is nothing less than a path to enlightenment. The best writers are the writers whose work is enlightened by experience and polished by craftsmanship. These are the writers who write with quiet hands.

Just like you.

Hands On

What’s the too-big story you think you aren’t able to write? Begin it.

“Because this business of becoming conscious, of being a writer, is ultimately about asking yourself, ‘How alive am I willing to be?’”

—Anne Lamott