CHAPTER 8

Resource exhaustion

We buy a wastebasket and take it home in a plastic bag. Then we take the wastebasket out of the bag, and put the bag in the wastebasket.

—LILY TOMLIN, COMEDIAN

Since the earth is finite, and we will have to stop expanding sometime, should we do it before or after nature’s diversity is gone?

—DONELLA MEADOWS

In case our society needs one more recipe for disaster, the Daily Grist writer Jim Meyer thinks he has a winner. “Ever wonder about the future of energy?” he asks, as if earnestly. “Will it be wind? Solar? Geothermal? No wait, I got it, tar sands! … They’ve got everything oil does, but they’re harder to get, crappier when you get them, and leave a much bigger mark on the climate.… Tar sands are deposits of about 90 percent sand, water, and clay mixed with only about 10 percent high-sulfur bitumen, a viscous black petroleum sludge containing hydrocarbons, also known as ‘natural asphalt.’” Referencing the proposed Keystone XL Pipeline (which, if built, would originate in tar-sands-stricken Alberta, Canada), Meyer says, “It would pump 1.1 million barrels of bitumen sludge a day, crisscrossing much of the continent’s freshwater supply, all the way to the Gulf of Mexico.”1

The first step, he instructs, is to clear-cut the unsightly boreal forest in Canada—and many of its indigenous plants and animals. Then, “get yourself some massive excavators, the biggest moveable objects on the planet, each capable of gouging out 16,000 cubic meters of earth an hour, and ripping pits into the planet fifteen stories deep.” After crushing the sand boulders with gigantic machines and adding solvents to make the final slurry transportable, you’re ready to start cooking up a batch of tar sands. But there’s a glitch: “Somebody added solvents to our tar,” Meyer notes, “so here comes the hydro-treating that removes the solvents, nitrogen, sulfur, and various metals. The process uses a lot of water and energy in the form of natural gas and oil. (Hey, what are we trying to make again?) Next, heat it again to remove carbon and add hydrogen, then it’s off in another pipeline to an oil refinery, though most of the old refineries aren’t up to the task of handling the filthy bitumen, so you’ll need to build new refineries or upgrade old ones. Presto! You’re cooking with gas!”

It takes about four tons of sand and four barrels of fresh water to make a barrel of synthetic oil, which is good for about forty-two gallons of gas, or one fill-up of a respectable-size SUV. “The good news is about 10 percent of that water is recycled!” says Meyer. “On the downside, the other 90 percent is dumped into toxic tailing ponds, which currently cover about 19 square miles along the Athabasca River, and are leaking into the ecosystem at a rate of perhaps eleven million liters a day.”2

WARNINGS FROM THE PAST

Our thanks to the tireless researchers and writers at Grist, who, even while covering environmental disasters day after day, can maintain a (caustic) sense of humor. Meyer’s point, of course, is that we’ll never again inherit a 150-year portfolio of easily accessible petroleum and that we’d better stop pretending we’re somehow entitled to buy and sell cheap energy. As participants in a global economy, we’re writing checks that have a high probability of bouncing very soon. Our overconsuming way of life is drawing down natural capital—the real principal in our account—consisting not only of petroleum and metals but also water, farmland, trees, climatic stability—at rates never seen before on this side of the universe. We’ve hit a tipping point: until we change our lifestyle to one that’s culturally richer but materially more efficient and moderate, we’ll risk cardiac arrest at a civilizational scale. (Not a pretty thought … we’re talking about hurricanes like Katrina and Sandy every year, up and down the world’s coastlines.) Historians have observed a handful of recurring symptoms in civilizations whose practices, beliefs, and habits eventually proved lethal. No surprise that they look all too familiar:

• Resource stocks fall; wastes and pollution accumulate.

• Exploitation is undertaken of scarcer, more distant, deeper, or more dilute resources (which are invariably more expensive).

• Natural services like water purification, fisheries, and flood control become less effective, requiring artificial substitutes like fish farms, bottled water, and engineered levees and barrier walls.

• Chaos in natural systems grows: more natural disasters, less biological resilience.

• Demands grow for military or corporate access to more remote, increasingly hostile regions.3

Why is our global economy resorting to environmentally and socially destructive technologies like fracking to get at natural gas, removing mountaintops to mine coal, and drilling from mile-deep, risky offshore rigs to slurp ancient oil deposits? Because easily mined resources are rapidly becoming a thing of the past. There are measurable limits to growth, and we are bumping up against them. Why has fish farming become a sizable, biologically unstable industry in the last decade? Because we’ve overfished many of the world’s oceans and lakes. (Pacific bluefin tuna is now so scarce that sushi restaurateurs recently bid $1.7 million for a single, jumbo-size fish in Tokyo’s Tsukiji fish market!) Why is the insurance industry so spooked by the stark realities of climate change? Because there’s growing chaos in natural systems—in 2012, the hottest year on record, damages in the United States from natural disasters like floods on the East Coast, forest fires in the Rockies, and deep drought in Texas came to $139 billion. (About a fourth of this was covered by private insurance; the rest was covered by the federal government, which effectively cost each American taxpayer about $1,100).4

Here’s a major part of the problem: “Industry moves, mines, extracts, shovels, burns, wastes, pumps, and disposes of four million pounds of material in order to provide one average middle-class family’s needs for a year,” write the coauthors of Natural Capitalism. Americans spend more for trash bags, golf balls, and bottled water than many of the world’s countries spend for everything. In an average lifetime, each American consumes a reservoir of water (forty million gallons, including water for personal, industrial, and agricultural use) and a small tanker of oil (2,500 barrels).5

Because few of us supply our own materials for daily life, almost everything we consume, from potatoes to petroleum to pencils, comes from somewhere else. “The problem is that we’re running out of ‘somewhere elses,’ especially as developing countries try to achieve a Western style of life,” says the Swiss engineer Mathis Wackernagel. Dividing the planet’s biologically productive land and sea by the number of humans, Wackernagel and his Canadian colleague William Rees come up with 5.5 acres per person. That’s if we put nothing aside for all the other species. “In contrast,” says Wackernagel, “the average world citizen uses more than 7 acres—what we call his or her ‘ecological footprint.’

“That’s over 30 percent more than what nature can regenerate. In other words, it would take 1.3 years to regenerate what humanity uses in one year.” He continues, “If all people lived like the average American (with thirty-acre footprints, we’d need five more planets.” (To find out the size of your own ecological footprint, take the quiz at the Redefining Progress website: www.myfootprint.org.)

Wackernagel observes, “We can’t use all the planet’s resources, because we’re only one species out of ten million or more. Yet if we leave half of the biological capacity for other species (or if the human population doubles in size), human needs must come from less than three acres per capita, only about one-tenth of the capacity now used by Americans.”6 The solution? No sweat, we’ll use the market, right? We’ll just go out and buy five more planets.

Let’s use more stuff!

SCRAPING THE BOTTOM OF THE BARREL

Vince Matthews, a former state geologist of Colorado, talks about resource pyramids a lot these days. What he means by this term is that when a mineral is first exploited, it’s highly concentrated, cheap, and easy to extract. For example, when copper was first mined, its concentration at or near the surface was 7 percent—a much higher quality than anything we now mine. As we move down the conceptual pyramid, the ore or mineral becomes more expensive to extract, partly because more energy is used to extract it. It’s a lower-quality resource, and even if there are thousands of such deposits, each one will be less profitable per dollar invested than what we’re used to. In many cases, it will also cause more environmental damage, as we rediscovered with the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill.7

Matthews gives the example of Bingham Canyon Mine, also known as Kennecott Copper Mine, near Salt Lake City. This huge open pit mine, about three-fifths of a mile deep and two and a half miles wide, has been extremely lucrative in its 107 years of operation: more than 17 million tons of copper and 23 million ounces of gold have graced the global economy so far. But in April 2013, nature tried to fill the pit back up: a landslide dumped 165 million tons of rock, dirt, and low-grade ore into the hole, a volume which, by one estimate, would bury a chunk of land the size of New York City’s Central Park 65 feet deep. At Bingham Canyon, it buried its fair share of mining equipment, including a small fleet of monster dump trucks each valued at more than $3 million. Though early warnings with seismic equipment prevented fatalities, this largest human-caused slide in history has resulted in hundreds of employee layoffs.8 Says Matthews, “It seems likely that the market price of copper will go up as a result.” He stresses that when resources are too low on the resource pyramid and too expensive, they’re not worth extracting. “We’re seeing this effect throughout the mining, drilling, and fracking industry,” he says. “The best way to keep remaining minerals affordable is to consume less of them.”

Because of its diverse properties, copper is of one humanity’s most strategic metals, used not only in electrical infrastructure, construction, and electronic circuitry but also in renewable energy technologies like wind generators and solar technology. For example, a single large wind generator (2.4 mW) requires more than eight tons of copper. If both the United States and China meet 2020 wind energy targets, where will 1.5 million tons of inexpensive copper come from? More than half of the copper ever used—in the last ten millennia—was extracted in the past twenty-four years, and by some estimates, this metal will be too low on the resource pyramid to mine within forty or fifty years.9

Similarly, if the world’s overdeveloped nations bring millions more hybrid and electric vehicles into the global fleet, the demand for rare earth elements like neodymium, lanthanum, and cerium (with unique luminescent, catalytic, and magnetic properties) will skyrocket. The United States has a slight problem here: China has been very busy making deals. While the US snoozed, it signed supply contracts all over the world on these high-tech metals, and 97 percent of the rare earth reserves are now controlled by this new superpower, whose leaders plan to use their near-monopoly strategically.10 In a recent skirmish with Japan over territorial waters, China threatened to cut off Japan’s supply of rare earth elements, a hammerlock that prompted the Japanese to immediately release the Chinese ship captain they held in custody.

The picture is not rosy for petroleum, either, despite low-pyramid discoveries in North Dakota, offshore Brazil, and elsewhere. “In fifty-four of the world’s sixty-five oil-producing countries, oil production is declining,” Matthews reports. “So we’d have to discover new reserves every day to make up for an overall 5 percent decline annually in production. And the top of the petroleum pyramid will never be seen again.” Matthews is most concerned not about minerals, but fertilizer, the price of which is on a steadily upward trend. Again, China’s consumption of fertilizer has increased 800 percent since 1990, causing many farmers around the world to rethink the way they grow their crops.11

Says Lester Brown of Earth Policy Institute, “We still talk about the gold rushes of the nineteenth century, but in today’s world, land is the new gold.”12 Countries such as China, Saudi Arabia, and South Korea are leading a neocolonial charge to acquire farmable land. Why the land grabbing? Because the most valuable commodity of all, grain, is also becoming scarce on the market. In 2007, world grain production fell behind demand, largely because of drought. Leading grain exporters like Russia and Argentina began to lower their exports to keep domestic food prices down, and Vietnam, the world’s second-largest rice exporter, banned exports altogether for a few months. A 2011 World Bank analysis reported that at least 140 million acres have been leased or purchased, mostly in Africa—“an area that exceeds the cropland devoted to corn and wheat combined in the United States.”13

We don’t hear these kinds of reports on popular news programs, partly because advertisers indirectly or directly control what gets reported, but data like this leaves us wondering, what will happen? Are we headed back to the Stone Age? No, but since we can’t change the shapes of these various resource pyramids, we have to change ourselves instead. We’ll have to make it immoral and even illegal not to recycle all resources. The European Union has experimented successfully with “extended producer responsibility,” which requires manufacturers to take back products at the end of their useful lives, so the materials can be recycled. Certainly, if consumer expectations come back down from the stratosphere, resource demand will fall, and so will prices, as they did during the Great Recession. Although the United Nations has recently released reports about the “underutilized” protein content of insects, not many Americans would step up to that plate. Yet there is a growing sector of the American population that already practices “meatless Mondays” to reduce both the amount of grain inefficiently fed to livestock and the health risks to themselves. More efficient vehicles, more durable products, more decentralized and renewable energy production, the restoration of naturally productive ecosystems, an increase in renting and sharing rather than buying—all these are pieces of a sustainable, culturally abundant economy.

“CAN’T WE KEEP PLUNDERING, FOR JUST A LITTLE WHILE LONGER?”

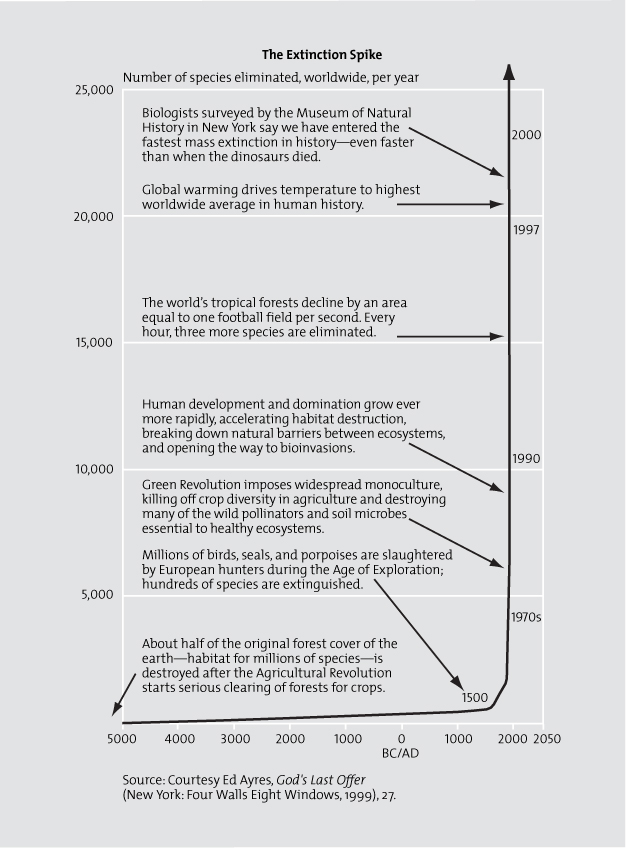

What must the world’s animal species think of us? Surely they wonder why we are so industriously disassembling the habitats that mutually support us. For example, because of disease, rising ocean temperatures, pollution, and other stressors, huge coral reefs that were here when Columbus sailed in the Caribbean have died off in this decade. As glaciers and icebergs melt, and prairies disappear under suburban developments, species scramble to make a living. The changes are too fast for maple trees and coffee plantations to move north or for polar bears to swim twice as far to hunt seals (their hunting bases—the icebergs—have melted). Before nature’s health began to slide, we rarely thought about how a product got to us; we just consumed it and threw the leftovers away. We didn’t think about the plants, animals, and even human cultures that were displaced or destroyed when the materials were mined. Now, when biologists like Norman Myers and E. O. Wilson tell us we may be in the middle of the most severe extinction since the fall of the dinosaur sixty-five million years ago, many are slowly moving beyond denial.14 We are losing species a thousand times faster than the natural rate of extinction.

Depressed yet? Facts like these hit us like urgent, middle-of-the-night phone calls, don’t they? They leave us with two distinct choices: either stay informed, get involved, and help create the values shift we so desperately need, or on the contrary, do nothing. Sit on the sidelines with our digital devices, pretending everything is fine. People like Tim DeChristopher and Bill McKibben have opted, heroically, to get busy, to become culture changers. DeChristopher just served twenty-one months in federal custody for a single act of civil disobedience: the Bureau of Land Management was auctioning off leases to drill for oil and gas on public lands, and although DeChristopher didn’t have the capital, his winning bids for 22,500 acres came to $1.8 million (which he later raised from donations). This nonviolent, confrontational act helped shift the environmental movement into a different gear. At the 2011 Power Shift conference in Washington, DC, he inspired listeners to honor their convictions: “We hold the power right here to create our vision of a healthy and just world, if we are willing to make the sacrifices to make it happen,” he said. “Climate Change and the injustices we are experiencing are not being driven solely by the coal industry, lobbyists, or politicians. They’re also happening because of the cowardice of the environmental movement.”15

Sentiments like these helped inspire acts of nonviolent civil disobedience, as in the arrest of 1,253 protesters of the Keystone XL pipeline. At the Forward on Climate rally in Washington, DC, McKibben was arrested, along with Sierra Club’s executive director, Michael Brune, who broke with the organization’s 120-year tradition barring civil disobedience. McKibben, whose 1989 book The End of Nature pioneered public awareness of climate change, has become a reluctant hero on the environmental front, founding the influential 350.org in 2008 to educate and advocate about climate change. More than five thousand demonstrations in 181 countries made the 350.org International Day of Climate Action in 2009 a rousing success, and an estimated fifty thousand people showed up at the Forward on Climate rally in 2013, where McKibben praised the large crowd for being “antibodies kicking in as the planet tries to fight its fever.”

McKibben’s most effective messaging so far may be the organization’s 2012 “Do the Math” lecture series, in which he and his team traveled across the United States in a bus, stopping in twenty-one cities to present the urgent nature of climate change. The lectures spotlighted the number 2 degrees Celsius—a limit accepted by most global leaders as the official “line in the sand” that must not be crossed. To keep the planet’s average temperature below this target (and preserve life as we know it) we’ll have to release no more than 565 gigatons of carbon dioxide. Yet, the fossil fuel industry already has five times that amount (2,795 gigatons) of carbon in their reserves. Reporting that the huge energy companies (Exxon, Shell, BP, Chevron, Conoco Phillips) receive $6.6 million a day in federal subsidies, McKibben concludes, “We’re paying them to keep polluting.”16 These companies also spend a combined $100 million a day to explore the furthest reaches of the planet for more profitable oil, and $440,000 a day to lobby Congress. Rex Tillerson, CEO of Exxon, receives about $100,000 a day and has recently acknowledged that human-caused climate change is indeed a reality, yet with a shrug, he assumes that “people will adapt.”17 The question is, can he sleep at night?

DeChristopher’s passionate final statement at his jail sentencing in 2011 is a harbinger of the outrage that is finally stirring in the ranks of citizen activists. Referring to environmental activism, he said, “At this point of unimaginable threats on the horizon, this is what hope looks like. In these times of a morally bankrupt government that has sold out its principles, this is what patriotism looks like. With countless lives on the line, this is what love looks like, and it will only grow.”18

ON THE PAPER TRAIL

On a sixty-mile hike on Vancouver Island’s West Coast Trail, Dave’s then sixteen-year-old son, Colin, and he got the value inherent in unmarketed, pristine nature—in their lungs, and in their senses—especially the sense of being alive. They realized, You don’t need as much stuff when you genuinely appreciate the value of what’s already here. As their heads cleared, other forms of wealth besides money came into focus: the biological brilliance of the rain forest and ocean around them, the social and cultural wealth of the indigenous inhabitants of Vancouver Island, and health, surely the most valuable wealth of all.

Originally constructed as a survival route for shipwrecked sailors, the West Coast Trail provides spectacular vistas of bright blue ocean and white, pounding surf, often through dark silhouettes of shady rain forest. Tide pools filled with starfish and crabs, families of bald eagles soaring silently overhead, and the breathing spouts of hundreds of humpback whales all speak of nature’s abundance.

Yet the beaches were littered with the trunks of dead spruce and fir trees, river-borne escapees from a logging industry that has transformed much of the island’s natural capital into barren terrain. One photograph from that trip shows Colin standing on a sawed-off trunk the size of a small stage. He and his father were graphically reminded that many of the products they consumed back home had their beginnings in this particular bioregion, where 10 percent of the world’s newsprint comes from.

If asked that week what Vancouver Island was good for, the father and son probably would have said in exhilaration, “Wilderness. Let it regenerate.” If the logger whose flatbed-semi can transport three 80-foot tree trunks had been asked the same question, he’d have said, “Timber. Let me harvest it.” The issue isn’t a simple one, especially since Americans consume a third of the world’s wood. Yet, after returning home from their travels in Canada, Dave resumed his higher-than-average consumption of paper, being a writer, while the logger probably looked for a nearby pristine place to take his kids for a hike, being also a father.

The fact is, logging practices like these force society to work harder. Though difficult to track directly, water utility bills go up when logging sediments pollute rivers that supply drinking water. Taxes go up when roads and bridges are washed out by floodwaters that run off clear-cut land. The price of lumber and paper goes up as companies feel compelled to advertise how “green” their practices are. In short, we each write checks and work extra hours to smooth over our collective “out of sight, out of mind” sloppiness.

WHAT HAPPENED?

What will civilizations of the far future say about our careless consumer era? Will they somehow deduce the causes of the calamitous decline in species diversity? Or will they shrug their shoulders (if they have shoulders to shrug), the way our scientists do when they ponder extinctions and collapses of the past? “It was climate change,” the future scientists might conclude. “Inefficient use of land,” others will hypothesize. But for the sake of our civilization’s dignity, let’s hope that none of them uncovers humiliating evidence of our obsessive, oblivious need for cheap processed snacks, gasoline, digital games, and underwear.