11

Transformative Learning during Dialogic OD

“I want more than change, I want transformation!”

This statement and variations of it are popular among organization leaders today. Leaders are aware that in the face of constant change and increasing complexity, they need employees and workgroups that are able to build their own capacity to solve the complex adaptive challenges of our times (Heifetz, Linsky, and Grashow, 2009). They want people and groups in their organizations who are capable of anticipating and integrating the constant influx of internal and external changes, making meaning of the changes, and taking the right action to move the organization forward. Informed leaders are aware this requires shared accountability and distributed leadership at every level over and over again … as quickly as changes appear on the landscape. They know these desired outcomes require a shift in the mindset and culture of their organizations to foster nimble and adaptive transformative capacity. In this chapter I will review a model that provides useful tools and advice for working with sponsors in the personal transformational change process any successful organizational transformation will require of them. The model also offers useful tools and advice for working with the people who will have to engage in the Dialogic OD process, and ultimately go through personal transformation themselves.

Transformational change is continuous, emergent, and complex, involving many individual agents/systems and many factors, in contrast to an episodic, well-defined, and time-bound change event (Marshak, 2002). Transformational change is usually influenced by the interconnection between the external and internal environments, resulting in a radically new mission and strategy, leadership, and overall culture of an organization. In sum, transformative change represents change that fundamentally shifts “how we think,” “how we do our work,” and “who we are” in organizations. It is a shift in the collective organizing premises and identity of individuals within the organization. There are a dizzying number of terms and perspectives that have been developed to refer to these fundamental shifts in individuals, leaders, and systems and a great focus in the literature on the leadership required to achieve this type of change (Anderson and Ackerman-Anderson, 2010; French and Bell, 1999; Lee et al., 2013; Pearson, 2012; Poter-O’Grady and Mallo, 2011; Quinn, 1996; Weick and Quinn, 1999). Dialogic OD as a distinct approach has made the linkage between OD and transformational change clearer. Transformational change emerges when actors self-organize to coconstruct and sustain generative images of their futures, which disrupts the status quo through narrative/discursive meaning making (Bushe and Marshak, 2014a).

As a practitioner committed to fostering transformational change, I have built my own capacity to use Dialogic OD methodologies and continually work on developing what Bushe and Marshak have called a Dialogic Mindset. A Dialogic Mindset, as discussed in Chapter 1, is a perspective centered in the principles and premises of social constructivist, interpretive, and complexity thinking (Bushe and Marshak, 2014b). Bushe and Marshak’s assertion that transformative change is an explicit intention of Dialogic OD practice therefore did not surprise me—it aligns with my experiences. However, it also brought to the foreground a different theoretical lens that has informed my Dialogic OD practice because of a gap I perceive in the literature on organization transformational change. That gap is found in descriptions of leadership or change-planning strategies for supporting transformational change that lack adequate exploration of the underlying transformational processes that must occur (Lee et al., 2013). Questions about the transformational change process that have been largely unaddressed include: What is the underlying process that individuals in transformational change experience? What are the underlying processes that groups and systems experience that result in organization transformation? From an OD practice perspective, I believe understanding these underlying change processes is essential to facilitating successful transformational approaches.

I have gained some understanding of these underlying processes from transformative learning theory, with its roots in adult education and critical social change (Cranton, 2006; Mezirow and Taylor, 2009; Taylor, 2009). This literature has not only defined a transformational learning process, but has articulated strategies for facilitating transformation in individuals and larger collectives. This chapter briefly outlines the core theories of transformative learning that have informed my practice, then outlines the connections between transformative learning and Dialogic OD, and concludes with the facilitative strategies, examples, and learnings I have gleaned from the integration of transformative learning into my Dialogic OD practice.

Transformative Learning Theory

Transformative learning perspectives are often distinguished in terms of the dimensions of the unit of analysis (individual or social change) and the internal processes that influence change (rational or extrarational processes). There is considerable debate on the impact of the fragmentation and integration of these perspectives on transformation theory (Cranton and Taylor, 2012; Dirkx, Mezirow, and Cranton, 2006; Merriam, Caffarella, and Baumgartner, 2007). However, what unites these perspectives is that they are all founded on humanistic and social-constructivist premises. They all propose a transformation in ways of thinking or being through a process of learning, as evidenced in a changed narrative, outlook on life, and resulting actions.

The foundational individual, rational perspective in transformative learning is that of Jack Mezirow and associates (Mezirow, 1991, 2000a, 2009). For Mezirow, “transformative learning refers to the process by which we transform our taken-for-granted frames of reference (meaning perspectives, habits of mind, mind-sets) to make them more inclusive, discriminating, open, emotionally capable of change, and reflective so that they may generate beliefs and opinions that will prove more true or justified to guide action. Transformative learning involves participation in constructive discourse to use the experience of others to assess reasons justifying these assumptions, and making an action decision based on the resulting insight” (Mezirow, 2000b, pp. 7–8).

Fundamental to this process is the assumption that engaging in transformative learning requires a context of “values like freedom, equality, tolerance, social justice, and rationality [to] provide essential norms for free full participation in discourse, that is, for fully understanding our experience” (Mezirow, 2000b, 14). Mezirow (1991, 2000b, 2009) has offered a linear ten-phase process of transformative learning, as follows:

1. a disorienting dilemma

2. self-examination with feelings of fear, anger, guilt, or shame

3. a critical assessment of assumptions

4. recognition that one’s discontent and the process of transformation are shared

5. exploration of options for new roles, relationships, and actions

6. planning a course of action

7. acquiring knowledge and skills for implementing one’s plans

8. provisional trying of new roles

9. building competence and self-confidence in new roles and relationships

10. a reintegration into one’s life on the basis of conditions dictated by one’s new perspective.

Because Mezirow offers a predominantly rational perspective on transformation, it is important to note the work of researchers and theorists who have contributed to extrarational understandings of transformative learning (Dirkx, Mezirow, and Cranton, 2006; Easton, Monkman, and Miles, 2009; Hyland-Russell and Groen, 2008; Johnson-Bailey, 2012; Lange, 2004; Merriam, Caffarella, and Baumgartner, 2007, 141; Ntesane, 2012; Taylor, 2000; Taylor and Cranton, 2012; Tisdell and Tolliver, 2003). This is because extrarational perspectives are significant within a Dialogic OD Mindset, which acknowledges the whole person including the emotional and spiritual selves, and entails processes such as the use of narratives and the arts (Bushe and Marshak, 2014a). In addition, though Mezirow focuses on individuals, sociocultural perspectives provide understandings of transformational change processes that can be applied at a group and social-system level (Brookfield, 1986; Freire, 1970). Mezirow’s ten-phase process and these additional extrarational and sociocultural dimensions will be discussed and illustrated in the context of explaining my practice.

Implications of Transformative Learning for Dialogic OD Practice

A comparison of Dialogic OD and transformative learning shows a great deal of alignment between their underlying philosophical premises/foundations, the process of transformation, and the outcomes signifying transformation. These are summarized in Table 11.1.

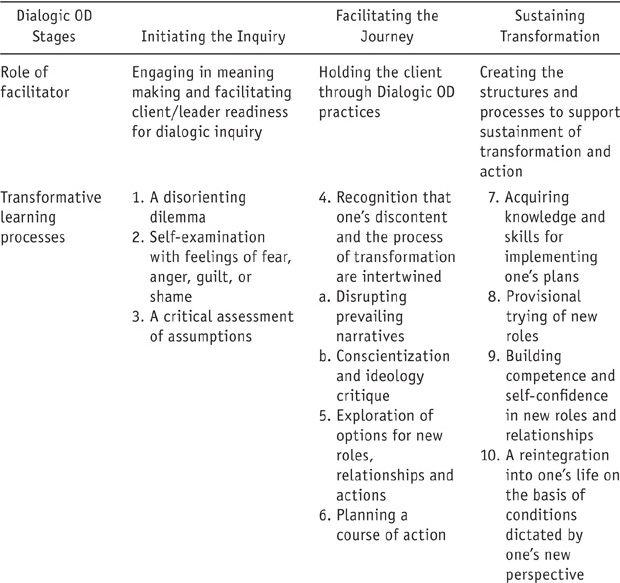

The question I will try to answer here is how, based on ideas and practices from transformative learning, can Dialogic OD practitioners foster the conditions for transformational change to occur in organization systems? To respond to this question I present cases, examples, and vignettes from my past experience. All names are fictional or disguised unless otherwise stated. I have organized my examples based on three Dialogic OD stages I have labeled “Initiating the Dialogic Inquiry,” “Facilitating the Dialogic Journey,” and “Sustaining the Transformation.” First, I present two scenarios and then explain my thinking and approach to fostering transformative learning throughout these three Dialogic OD stages.

The Case Examples

Mary is a senior leader committed to transformational leadership. In her previous organization there was a system-wide commitment to humanistic values such as compassion and respect for all. High-quality “work” seemed to happen seamlessly because there was a high degree of trust. Mary asked to meet with me to discuss her vision of creating a similar culture in her current organization. She intended to start with her own leadership team of eight and then bring together the extended and geographically dispersed leadership team of up to 120 people. In our initial meeting, she described the positive impact on her of working and leading in a culture in which everyone was so aligned, and her desire to create similar outcomes. She described a current scenario where she worked with “good” people who had varying levels of leadership development and preparedness, working hard but not necessarily maximizing the possibilities around them. She described what she interpreted as a sense of resignation and defeat among her core and extended leadership teams regarding the “sticky” (constantly recurring yet unaddressed) issues they faced. The central questions I asked of Mary to initiate this dialogic inquiry were:

Table 11.1 Dialogic OD and Transformative Learning Theory

Dialogic OD |

Transformative Learning |

|

Philosophical/Social Science Orientation |

||

Social science perspective |

Interpretive approaches, social constructionism, critical and postmodern philosophy |

Social constructionism, critical social science, postmodernism, interpretive approaches |

Dominant organization |

Organizations are |

Individuals are meaning- |

construct |

meaning-making systems, dialogic networks. |

making beings. |

Epistemology/ontology |

Reality is socially constructed and there are multiple realities. |

Reality is subjective and socially constructed. Therefore there are multiple realities/perspectives. |

Core values |

Democratic, humanistic and collaborative Inquiry |

Democratic, humanistic and collaborative Inquiry |

Change Process/Conditions |

||

Concept of change |

Emergent, continuous, transformational |

Transformational |

Unit of change |

Organization |

Individual / Society |

Change methods |

Inquiry, narrative, reflexivity, generativity, emergence |

Critical reflection (o bjective / subjective), discourse, narrative/story-telling, arts |

Inner processes influencing change |

Holistic person (physical, emotional, intellectual, spiritual) |

Rational (cognitive) and extrarational (affect/emotion, spiritual, unconscious/psyche, inner soul, etc.) |

Role of change agent |

Immersed with/Part of Interactions |

Immersed with/Part of Interactions/Setting conditions for transformation |

Goal of change process |

More complex, adaptive reorganizing, disrupting prevailing narratives, engaging multiple perspectives, generativity |

Inquiry, changed worldview (more complex reorganizing of thought), disrupting prevailing narratives, engaging multiple perspectives |

Emphasis for change |

Mindset/relational/organizational |

Mindset/relational(communicative)/life change |

Mindset change |

Generativity and disruption in social reality can Lead to new thinking and acting. |

Disorienting dilemma or challenged assumption Leads to more complex reorganizing of thought. |

Narrative/Life world/Being change |

New core organizational narrative |

New individual/social narrative |

Vision and action change |

Generativity and action to meet adaptive challenges |

Action aligned with changed worldview and narrative |

![]() What needs to be different as a result of bringing your leadership teams together?

What needs to be different as a result of bringing your leadership teams together?

![]() What would a breakthrough outcome look like for your most pressing sticky issue?

What would a breakthrough outcome look like for your most pressing sticky issue?

![]() What must the leadership do to speak and radiate possibility for yourselves and your teams?

What must the leadership do to speak and radiate possibility for yourselves and your teams?

As a second example I offer Doug and Susan. Doug (a vice president) and Susan (a human resources leader) were the internal team responsible for a large-scale organization change that would engage up to two thousand employees, setting the course for a new strategic vision and a more engaged workforce. Their context at the time was a traditional hierarchy, organized in functional silos, where the employee experience was one of being “told.” The idea of engaging the whole system had been received with skepticism until the point of my entry with a colleague as a cofacilitation pair. Employees feared dialogic events would, at best, be acts of performance to mask leadership decisions that were already made. In initial meetings I observed Doug speaking simultaneously about giving control to employees, while expressing a desire to “control” and “manage” the engagement process. The central questions with this client group to initiate the inquiry were:

![]() What would an engaged workforce with the full discretion and freedom to make and act on their own identified futures require of leadership?

What would an engaged workforce with the full discretion and freedom to make and act on their own identified futures require of leadership?

![]() What new possibility for leadership would this “letting go” present for you (Doug and Susan)?

What new possibility for leadership would this “letting go” present for you (Doug and Susan)?

I am sure that these two scenarios will be familiar to experienced consultants. So why did I pose those particular questions and what did they contribute to the Dialogic OD practices and transformations that ensued?

Stage 1: Initiating the Dialogic Inquiry

I have learned that at the stage of initiating the inquiry, my role is not only to make sense and meaning of the situation with the client, but also to test and prepare the client for the potential dialogic journey with the broader system ahead. I believe in the social-constructivist principles of Dialogic OD and transformative learning that every interaction and inquiry is an intervention resulting in meaning making and change, and therefore invite inquiry and dialogue to evoke transformation right from the start. Right from the very first interaction I engaged with my clients from a place of inquiry and joint meaning making, using the first three phases of the individual transformative learning process outlined by Mezirow as a guidepost. Once again, the first three phases are:

1. a disorienting dilemma

2. self-examination with feelings of fear, anger, guilt, or shame

3. a critical assessment of assumptions.

Disorienting Dilemmas

One of the core skills to facilitating these first three phases is posing questions that highlight the disorienting dilemmas inherent in the client’s situation in a way that invites critical assessment of assumptions (Cranton, 2006). The disorienting dilemma is a disruptive impetus for transformation—the signal that I am faced with a situation that does not fit with my taken-for-granted ways of knowing and being. Disorienting dilemmas present the possibility for learning that will expand frames of reference and result in a higher level of functioning in individuals and organizations. The disorienting dilemma for Mary was a sudden realization that she was now in an organizational context in which the humanistic values and ways of working she was accustomed to were not shared as common practice, even though there were definitely humanistic values “espoused” in her new context. For Doug and Susan, the disorienting dilemma was that they had the mandate and the desire to lead in engaging ways, yet were struggling with the tension inherent in giving up the leadership control they were accustomed to. The inquiry questions were specifically designed to invite exploration of the disorienting dilemma in a way that moved the client toward the critical reflection and assessment required for transformative learning. Before encouraging critical assessment, however, it is crucial to take stock of the range of feelings a disorienting dilemma can evoke.

Self-Examination of Feelings

In my experience, the emotional journey (feelings of fear, anger, guilt, or shame) depicted as phase two of the transformative process continues throughout the processes of facing the disorienting dilemma as well as the critical assessment of underlying assumptions that follows. In working with clients, I can often see through their nonverbal tones and gestures, and hear in their emotive words and descriptions a deep experiential disquiet from the dilemma they face. This second phase of the transformative learning journey is usually a major sticking point. Facing their dilemma requires self-examination, and that can evoke emotions of fear, anger, guilt, or shame that must be acknowledged and worked with. I have found what Cranton (2006) calls spiraling and feeling questions the most useful in helping clients name and explore the impact of their emotional states on the change process. This in itself facilitates transformation. Spiraling questions evoke the linkages, impacts, and connections between all the parts of one’s experience. In organizational contexts, the most effective spiraling questions uncover the layers of complexity in the change and focus attention on the bigger picture or higher purpose. These include questions such as: What is the larger intent? What is the big picture? Why does this matter? What will be the impact of this change on people, roles, the organization, the industry, and so on? For example, a spiraling question to Mary such as, “What would be the impact on the system if your vision were realized?” might evoke a systems perspective on why her vision was important.

From Cranton’s (2006) perspective, the intent of feeling questions is to uncover the emotional domain relative to the dilemma and self-examination required. Direct feeling questions are a straightforward inquiry to ensure awareness of feelings at this stage. These are questions such as: How do you feel about your vision for change now? What are you feeling now? Furthermore, I have found inquiry that personalizes the impact of a change, countering the discomfort of a disorienting dilemma by evoking images and feelings associated with positive experiences, is very useful in propelling clients forward. These types of feeling questions and inquiry are what I call personalizing inquiry. I use feeling questions that personalize experience for clients such as: What would this mean to you? What transformation do you long for in this situation? In Mary’s case, a personalizing question such as “What would accomplishing this mean to you?” and a direct feeling question such as “How would it make you feel?” helped create positive, affective images whose realization made it worthwhile for her not to act on limiting emotions.

Other transformative learning strategies I have found useful for moving clients through the anxiety and fear that confronting dilemmas and self-examination of assumptions can evoke are examining critical incidents and consciousness-raising exercises and challenges (Cranton, 2006). A critical incident is an incident that stands out as especially positive or negative. The Appreciative Inquiry interview reflects a positive approach to the use of critical incidents for transformative learning and generativity and is a common practice to help clients see that what they want more of already exists (Cooperrider and Whitney, 2007). It reminds clients of the many transformations they have already successfully navigated, in spite of the initial discomfort and emotional turmoil associated with pending change.

Consciousness-raising experiences are less used in dialogic practice and entail putting people in real or simulated conditions to challenge their taken-for-granted ideologies/philosophies or roles. The original T-group and other laboratory learning processes, role-playing, simulations, recounting life stories, and writing autobiographies to help reveal the subconscious assumptions guiding one’s thoughts and behaviors have been used by OD practitioners. I encourage clients to (re)write, literally or figuratively, the story or narratives impacting them and their systems to unlock self-examination and transformation potential. This practice requires unpacking the emotions inherent in the old as well as the emerging narratives (see Chapter 16 for more discussion of reauthoring narratives). In addition, the experiential component of interactive consciousness-raising activities can unlock possibilities and awareness that lead to broadened perspectives.

The example below shows how consciousness-raising activities often allow for both self-examination of feelings and starting the transformation learning phase of critical assessment that comes next.

Doug and Susan repeatedly justified their actions to maintain control of their work through stories of what they had heard about employees not being willing to trust them or play fair. Another common narrative was that employees were continually asked for their input and yet offered few opinions, hence creating the need to be “told” from Doug’s and Susan’s perspectives. To encourage them to examine their underlying fears and evidence of a counternarrative, my cofacilitator and I designed and held a truly engaging meeting with a small group considered to be among the most disengaged from the change process. We coached Doug and Susan to hold back on some of their usual behaviors and experiment with exhibiting other behaviors we thought would be useful to move the group forward. For example, we asked them to stop expressing emotion through visual cues of impatience and annoyance (high-pitched tones, interrupting others), pointing out employees’ shortfalls in the process, and telling. We asked them to instead try deep listening (without interrupting), genuinely inquiring to understand perspectives that differed from theirs, and openly describe their own fears and concerns about the process. We asked them to impartially observe what was happening in the room while subjectively examining their feelings in the process. In their private debrief afterward, both Susan and Doug spoke to their surprise at the amount of dialogue, meaning, and understanding the meeting had evoked. Employees had even offered solutions to address the fears and concerns they had named. Susan was also, more readily than Doug, able to attest that although she’d found holding back hard, she had realized that it was, in fact, her own mistrust, fears, and need to control that were in the way of fully engaging people.

As this example shows, my experience aligns with Taylor’s assertion that in practice, transformative learning is iterative and “more recursive, evolving, and spiraling in nature” than linear (Taylor, 2000, p. 290). The phases of transformation are distinct, but the processes that distinguish each phase can blend and recur in subsequent phases as part of the transformation process.

Critical Assessment

Critical assessment refers to the reflective examination of one’s assumptions in order to make meaning of experiences and arrive at new understandings or broadened perspectives. There are two forms of critical assessment during the third phase of the transformative learning process: objective reframing and subjective reframing. Objective reframing or critical reflection of assumptions entails assessment of the content, process, and basic premises in others’ narratives or tasks. Subjective reframing or critical self-reflection of assumptions is self-examination of the content (what), process (how), and premises (why) of one’s own assumptions, feelings, and so on (Mezirow, 1998; Taylor, 2009). Content assessment refers to awareness of what our taken-for-granted assumptions and beliefs are; process assessment refers to how we come to hold those assumptions or will come to a new frame of reference; and premise assessment refers to assessing the foundation of our belief systems (Cranton, 2006; Mezirow, 1998, 2000b).

The reality of initiating inquiry and working with clients in Dialogic OD is that successful work not only requires objective reframing or critical reflection of assumptions, it also requires subjective reframing, or critical self-reflection of assumptions. One thing I have found especially helpful in allowing my clients to engage their disorienting dilemmas while being able to critically reflect on their assumptions is to embed their dilemmas in questions that evoke generative images of the possibilities the dilemma presents. The intent is to encourage meaning making of new ideas that compel individuals and organizations to think and act in beneficial, new ways. While these would ordinarily be considered leading questions, the process is reminiscent of the confrontive inquiry technique in process consulting, which is a questioning technique for challenging clients to think in new ways (Schein, 1999).

For example, in Mary’s case, the first question, “What needs to be different as a result of bringing your leadership teams together?” was a content assessment question, designed to allow for critical self-reflection of her own assumptions, beliefs, and perceptions of her leadership team’s functioning by evoking the generative images of her preferred future. The second question, “What would a breakthrough outcome look like for your most pressing sticky issue?” was a process question because it implied a journey to a new future and a new narrative about possibilities. The final question, “What must the leadership do to speak and radiate possibility for yourselves and your teams?” was a premise self-examination question to evoke inquiry about why this leadership team would choose to be different. It was in essence questioning why this team would care about the new and generative idea of looking beyond basics to maximizing possibilities. In Doug and Susan’s case, both initial questions were premise self-examination questions. The questions were intended to evoke new and generative images of what a future with an engaged workforce and a new kind of leadership would look like. Because the dilemma they faced was fundamentally tied to the premise assumptions they had about leadership and what it meant to lead, until they were able to examine and transform those assumptions of leadership and engaged followership, content and process questions were likely to yield limited progress.

Transition to Facilitating the Dialogic Journey Stage

Once a client is ready and the intended Dialogic OD interventions have been outlined for broader engagement, the practitioner’s journey with the system is expanded. However, I have found that for the collective group to move forward into the emergence, generativity, and re-storying characteristic of Dialogic OD processes, people in groups must also individually transition through phases one through three. This iterative cycle through phases one through three for individuals in groups must occur before the collective group can move forward, and represents a kind of transitional state before the group can meaningfully engage in any form of Dialogic OD practice. People can be stuck, skeptical, or wary of organizational change where disappointments of the past result in some fear, mistrust, anger, or shame. Past failed change processes, perceived leadership failures, layoffs, and similar organizational changes can cast a shadow over all new initiatives. It is difficult to engage in joint meaning making, visioning, and cocreating a new future when limiting emotions and images are in the way. Until these experiences and associated feelings have been named and collectively processed, they remain in the way of progress. Therefore, there may be a need to facilitate people in groups through the first three phases of transformative learning before launching fully into a dialogic inquiry.

Individuals working through their own transformation in groups create an experience of alignment and collective readiness when the majority are able to engage in self-examination and let go of limiting feelings in favor of moving toward possibility. Witnessing one another’s vulnerability and individual transformations creates a deeper sense of commitment to a collective transformational journey. Not everyone must be ready to move, because individual transformation happens at different rates and is inherently tied to each person’s lived experience and history with change and transformation. My experience is that when the majority is ready, the collective will move forward. This may be because those who remain in earlier phases of transformation are inspired by others and develop a new trust that change and transformation are possible.

An important note is that those who have not engaged their own disorienting dilemma or worked through limiting feelings when the collective is ready to move are often seen as skeptical or “resisters” of change at this time. In this situation, the Dialogic OD practitioner working for transformation has a crucial role in both continuing to facilitate critical assessment and self-assessment for those at earlier stages, as well as helping those ahead to examine their assumptions, labeling, and narratives of “resisters.” As described in Chapter 15, every role taken in change has value from a dialogic inquiry perspective and “resisters” at this stage typify the “sensor role” by signaling warnings and different perspectives that must be examined. Often, the role of sensors is not appreciated by those who are ready to move forward quickly. The challenge is to find the balance between slowing down the group enough to engage in the transformative learning required to fully understand the perspectives and experiences of sensors, and supporting the momentum of forward movement into the dialogic journey and further transformations.

I have used the same principles of questioning and experiential consciousness raising in facilitating groups to move from what was, to what can be. In addition, I have come to view confronting a disorienting dilemma at the group or organization level as the means to disrupt prevailing social narratives. The work of disrupting prevailing narratives in Dialogic OD aligns with the transformational learning concepts of conscientization and ideology critique, which are the processes of becoming critically aware of oppressive or limiting beliefs in a system (Brookfield, 2000). Freire (1970) argues that becoming aware of the social, political, and economic contradictions that create oppressive situations and naming them (conscientization) is the first step toward taking action to transform the situation. The delicate art in Dialogic OD practice is confronting the organization system with enough information or disruptive experiences to create energy for forward movement, but not so much to induce paralyzing anxiety and a defensive, downward spiral into single-loop learning or a unilateral control mindset closed to possibilities (Argyris, 2005; Zander and Zander, 2000).

Change sponsors have to go through phases one through three during the initiating dialogic inquiry stage, but there is a choice whether to engage groups in those phases during stage one, initiating the dialogic inquiry, or as part of stage two, facilitating the dialogic journey. I believe the choice lies in the level of readiness of people in the group, which can be anticipated based on the extent to which people in the system express limiting emotions about the change dilemma. In situations where people in the system widely express feelings of fear, anger, guilt, or shame in initial dialogues, the transition group work must occur in stage one, before embarking on a large-scale dialogic journey. This was the situation in Doug and Susan’s case where there was widespread expression of fear and lack of trust for the change leaders. We therefore made the choice to repeat the consciousness-raising session with the employees they had considered to be most disengaged, described above, across other groups in the organization. Similar outcomes came from most sessions, and resulted in change champions emerging across various organizational groups even before the broader organization engagements took place. I believe this emergence of champions occurred because people were given the opportunity for joint meaning making to process and transition from the past.

With my client Mary, the widespread sentiment was that the dilemma presented an opportunity. We therefore decided to do the work of confronting the dilemma and providing opportunity for self-examination of feelings and critical assessment in stage two, as part of the first dialogic whole-group session. The whole leadership group was challenged using lessons from the musical arts such as a live demonstration of teamwork in jazz, orchestra videos, and the role of a music conductor, as an impetus to dialogue about great teamwork and the power of possibility. In so doing, they had to confront what that meant for their own leadership and had a spontaneous discussion of what they needed to “let go” of in order to be great.

Stage 2: Facilitating the Dialogic Journey

At the stage of facilitating the dialogic journey, phases four, five, and six of Mezirow’s ten-phase process now become salient. These next three phases of meaning making show how the individual is intrinsically connected to community by signaling the need for transformation within the context of the collective. The three phases again are:

1. recognition that one’s discontent and the process of transformation are shared

2. exploration of options for new roles, relationships, and actions

3. planning a course of action.

Recognition of Shared Discontent and Transformation

At phase four of the transformation journey, the motivation for transformation lies in the realization that the dilemmas, discontent, and overall yearning for transformation are shared. Facilitating this phase of transformative learning occurs by supporting the client through structured Dialogic OD processes such as AI, Open Space, World Café conversations, or dialogic process consulting, whereby narratives and patterns of organizing are jointly examined and transformed (Bushe and Marshak, 2014b). For example, in Mary’s case, the dialogic process entailed continuing the inquiry with her core leadership team, followed by a large-group session with all 120 leaders that was focused on the possibilities. In Doug and Susan’s case, whole-group sessions in which my cofacilitator and I used elements of dialogic process consultation (as described in Chapters 2 and 17 of this book) followed the small-group initiating inquiry sessions. Up to 80 percent of the staff who were locally available met in a series of conferences to examine the more engaged patterns and roles of leadership they wanted in their future and then self-organized to create that future.

In Mary’s case, leaders attested that they had increased motivation to take action because of the shared experience and dialogue they engaged in with their peers. They reported that the knowledge that they could talk to other attendees about their plans and experiences after the session created forward movement and change in itself. In Doug and Susan’s case, the change champions who emerged from the consciousness-raising sessions shared their stories and experiences and helped further the collective dialogue toward a shared vision for an engaged workforce. The result of this was a collective moving forward, with the emergent will of the majority motivating others to be part of the social movement. In follow-up research and evaluation of another similar Dialogic OD process, participants attributed their experiences of transformation to the knowledge that they were part of a community with shared purpose—a theme they described as a phenomenon of “all for one.”

Daloz’s (2000) work on transformative learning in social contexts provides four specific conditions and related recommendations for facilitating transformative learning for the common good. Two of those conditions are particularly helpful for facilitating the emergence of shared understanding and common visions. These are:

![]() The presence of the other, corresponding with the practice of inviting diversity into the room. This entails facilitating group conversations to simultaneously foster recognition of differences and willingness to examine those differences, while articulating one’s own voice. Daloz proposes inviting participants into dialogue while engaging in the “practice of holding their lives and convictions against the backdrop of radical doubt and unshakeable faith.” (Daloz, 2000, p. 118)

The presence of the other, corresponding with the practice of inviting diversity into the room. This entails facilitating group conversations to simultaneously foster recognition of differences and willingness to examine those differences, while articulating one’s own voice. Daloz proposes inviting participants into dialogue while engaging in the “practice of holding their lives and convictions against the backdrop of radical doubt and unshakeable faith.” (Daloz, 2000, p. 118)

![]() Reflective discourse, or the practice of active inquiry and dialogue through which we make meaning of our individual and collective experiences. Daloz proposes encouraging dialogue on the impact of social, in this case organizational, conditioning on the way things are, while supporting the emergence of generative images of new ways of organizing.

Reflective discourse, or the practice of active inquiry and dialogue through which we make meaning of our individual and collective experiences. Daloz proposes encouraging dialogue on the impact of social, in this case organizational, conditioning on the way things are, while supporting the emergence of generative images of new ways of organizing.

Through the simultaneous exploration of diversity and differing perspectives in the context of reflective discourse, participants attain broadened perspectives and shared agreements for a generative future with higher-order assumptions than before they engaged in dialogue. This is the result of the constructive discourse Mezirow (2000b) refers to, which requires active inquiry, dialogue, tolerance, and democratic values. In my experience, participants will often refer to this as a need to feel safe expressing their views and beliefs without fear of retribution. This reflective discourse, through dialogue with others, is central to the learning and transformation that become possible when we explore assumptions that have failed us in order to make new meaning of them.

Exploring Options for New Roles, Relationships, and Actions

In this phase participants move beyond collective visioning to explore ways to make the vision a reality. It requires the full range of ideation, prototyping, and trying out possibilities. This is the design phase of typical Appreciative Inquiry processes, and the modeling phase described in Chapter 15. The emphasis in this phase is on exploring and not on narrowing ideas too soon. In Mary’s case, the 120 leaders spent time together generating and sharing ideas while consistently coaching each other to remain open and unconstrained by the organizational limits that typically held them back from exploring. Participants were encouraged to challenge limiting beliefs that were raised against possibilities and to explore questions such as: What would it take to make this happen? What would it look like if this idea were a reality? What innovative ways already exist that would make this possible? Where in our system is this already happening?

Examining new roles and relationships also requires more than exploration. It requires actually trying out the new ideas, roles, relationships, and actions in order to further disprove limiting ideas. In this phase, I encourage participants to take on small projects and actions to test back at work. This was the case for Doug and Susan’s organization. At the end of the whole-system sessions, they were challenged to try out new ways of being and acting to increase engagement, and told there would be a chance to check in on those experiments at a later session. The intention of testing out ideas is to experience the impacts of the ideas before further discourse. In this way, ideas move from the abstract to the concrete, which helps individuals and groups converge on a single course of action as they move from visioning and exploring into taking action.

Planning a Course of Action

Planning to take action is essential to the transformative learning journey. From the perspective of Dialogic OD practice, planning for action is most successful when it is done through self-organizing and emergent action planning by those engaged in the process, and not through top-down or structured action plans for change. In the latter case, the power of the transformative learning processes in earlier stages gets lost to planned directives from hierarchical leaders, who may not understand the sentiments and motives for action that will keep people inspired and energized to take action for change. However, I believe the failure to create intentional but loose structures to amplify and sustain change results in limited action and in situations where participants report having had a great but ultimately irrelevant or “touchy-feely” group experience. Here, two recommended structures to promote self-organized action planning and action taking, from Daloz’s work on transformative learning for the common good, are instructive (Daloz, 2000). These are:

![]() A mentoring community, or in this case simply a community for action, which is naturally created through dialogic processes

A mentoring community, or in this case simply a community for action, which is naturally created through dialogic processes

![]() Opportunities for committed action with the corresponding practice of sharing learning, experiences, and dilemmas, and continuing to take action

Opportunities for committed action with the corresponding practice of sharing learning, experiences, and dilemmas, and continuing to take action

In Mary’s case, we worked with the collective to plan specific next steps after ideas were explored and shared. The specific planning for action then happened in the leadership community groups that were represented across the 120 leaders. Each leadership group confirmed the specific commitments that they would take action on after the conference. For Susan and Doug, the planning for action happened alongside the work done to plan exploratory experiences of alternative ways of engaging each other in the organization. In both cases, communities for action were automatically set up in the subgroups of functions or regional leadership communities. These subcommunities included opportunities for sharing experiences, mentoring, and peer coaching. In addition, follow-ups were scheduled for whole-system sessions where actions and learning would further be shared.

Stage 3: Sustaining the Transformation

In order to sustain Dialogic OD practice for transformation, my recommended strategy is creating opportunities for committed follow-up to check in on actions. I advocate creating a structure for bringing groups back together periodically until they have settled into their new narrative and built enough capacity for self-organizing without the practitioner. The final four of Mezirow’s ten phases suggest areas that are important to discuss and attend to at individual, group, and system levels to sustain transformation:

1. acquiring knowledge and skills for implementing plans

2. provisional trying of new roles

3. building competence and self-confidence in new roles and relationships

4. a reintegration into one’s life on the basis of conditions dictated by one’s new perspective.

To create forums for committed follow-up, I use regular check-in and debrief sessions with the client system for a time following dialogic events, as was the case with Doug and Susan. The intention of these follow-up actions is to build confidence and comfort in the new ways of being, thinking, and acting, so that they became the new norms—indeed the new taken-for-granted ways of being, until they prove ineffective to make meaning of new experiences and require transformation once again.

Follow-up sessions help participants share learnings, engage in critical reflection of their journeys, and continue to further action. In one case, I continued these sessions monthly and then bimonthly over an entire year before exiting the client system. To my knowledge, the transformations the group journeyed through were sustained following my exit, and the client system self-organized to continue the sessions. Participants reported noticing that the impact on their group when they did not check in was a downward spiral into old patterns. New patterns were sustained when they continued reflective dialogue and connection.

The four final phases of transformation highlight the need to embed and reintegrate new learnings to avoid a return to old and familiar habits. They also require, at the organizational level, creating the structures to support the transformation so that the benefits are not short-lived. These are the nurturing and embedding phases discussed in Chapter 15; Mezirow’s phases provide a lens for OD practitioners, sponsors, and change teams for understanding what individuals need when they are engaged in organizational transformation. In transformative learning practice, each of the final phases requires examining and responding to a set of corresponding questions as part of committed follow-up: What knowledge and skills do I already have and what knowledge, skills, and abilities do I need to build? How do I need to be (re) structured or what provisional roles do I need to be successful? What capacity (e.g., competence) and capabilities (e.g., confidence) do I need to be successful? What shifts and changes are required to sustain the transformative learnings that I have acquired? These were the types of questions that Mary’s leadership team generated and committed to acting and following up on, to harness and embed their transformative learnings. The ultimate test of transformation is phase ten of the transformative learning process, which is evidence that individuals and groups have reintegrated or redefined their lives by adopting new ways of being, thinking, and acting, consistent with their new perspectives.

An Ethical Note

It is important to note that in this work, I have had to caution myself and advise other practitioners to understand the limits and ethical boundaries of transformative learning. Individual transformation necessitates that clients confront how they think and who they are in ways that require delving into their psyches. This process of self-examination often requires intellectual, emotional, and spiritual reintegration of self. It is great when clients and groups have the level of development in all these areas that allows them to do this work solely through the coaching and inquiry of the OD practice. However, where deep psychological issues surface that may require counseling and therapy, these should be acknowledged and addressed through referrals to appropriate resources.

The Practitioner’s Transformative Learning Journey

Bushe and Marshak (2014b, p. 198) state that “the role of the consultant is to help foster or accelerate new ways of talking and thinking that lead to the emergence of transformational possibilities.” In order to do so, we can learn from Cranton (2006) that the practitioner must be capable of supporting a group process specifically for transformation, helping individuals and the group through personal psychological adjustments that may arise with disorienting dilemmas and disrupted narratives, and supporting participants’ actions. This requires mindfulness, humility, and authenticity on the part of the practitioner, among other OD skills described in Chapters 9 and 13 to foster dialogue. The authenticity required, outlined by Freire (1970), includes love for people, humility, faith in the power of people to create and re-create, trust and hope that meaning making will emerge along with critical thinking and ongoing transformation. Similar values and requirements for transformation are also discussed in many other chapters in this book. To authentically and successfully engage clients in a transformational journey, Dialogic OD practitioners must themselves be open and willing to be challenged and transformed throughout the process. This is the role I see for myself when I choose dialogic practice in helping the client system become aware of where they are and what they want in their future. I must hold them and myself through the emotional and psychological shifts in a process of becoming anew, and then be mindful to help them and myself synthesize who and what we have become. In this way, Dialogic OD practice means attending to and holding the reality of coconstructed meaning making, which means everyone engaged in the process will ultimately be changed and transformed through the learning.

The way I monitor myself to ensure I am creating an authentic space for transformation is what I call checking in with myself—the practice of asking myself the content, process, and premise questions that keep me continually transformed and in the space of possibility for myself and my participants. These include:

![]() What are my assumptions and beliefs about the client situation now?

What are my assumptions and beliefs about the client situation now?

![]() How am I experiencing the transformative journey as I cocreate it?

How am I experiencing the transformative journey as I cocreate it?

![]() What possibilities do I still see?

What possibilities do I still see?

![]() What connections and new possibilities do I see emerging?

What connections and new possibilities do I see emerging?

![]() How am I feeling about the process?

How am I feeling about the process?

![]() Who am I being/need to be so that the eyes of my cocreators will keep shining? (Zander and Zander, 2000)

Who am I being/need to be so that the eyes of my cocreators will keep shining? (Zander and Zander, 2000)

Table 11.2 Contributions of Transformative Learning to Dialogic OD Practice

Conclusion and Summary

This chapter has outlined the connection between Dialogic OD and transformative learning theory and shown how Dialogic OD practice can be further enhanced by incorporating lessons from transformative learning theory and practice. The key points are summarized in Table 11.2.

I have intended to show how familiar facilitation and group strategies can be intentionally used, from a different mindset, to foster transformative learning. The unique contribution of this work is that with knowledge of transformation theory, the OD practitioner choosing a dialogic approach can clearly delineate for a client what to expect when the client says: “I want more than change, I want transformation!” In previous writing, I provided a framework for determining when to engage in Diagnostic, Dialogic, or a blended OD practice on the dimensions of complexity and readiness, with a high degree of readiness being central to successful Dialogic OD practice (Gilpin-Jackson, 2013). Applying transformative learning to dialogic practice provides direction for facilitating that readiness when it is lacking, by helping hold the client through the initial emotional phases of the transformation journey. It identifies the depth of personal work and development required of the Dialogic OD practitioner, as well as the client system, to journey through transformation. Dialogic transformation of thinking, being, and doing/acting through transformative learning processes has to occur in individuals and groups; only then can the desired outcome of an organization-wide transformational change be attained.

References

Anderson, D., & Ackerman-Anderson, L. S. (2010). Beyond change management. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Argyris, C. (2005). Double-loop learning in organizations: A theory of action perspective. In K. G. Smith & M. A. Hitt (Eds.), Great minds in management (pp. 261–279). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Brookfield, S. (1986). Understanding and facilitating adult learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Brookfield, S. (2000). Transformative learning as ideology critique. In J. Mezirow (Ed.), Learning as transformation (pp. 125–150). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bushe, G. R., & Marshak, R. J. (2014a). The dialogic mindset in organization development. Research in Organization Development and Change, 22, 55–97.

Bushe, G. R., & Marshak, R. J. (2014b). Dialogic organization development. In B. B. Jones & M. Brazzel (Eds.), The NTL handbook of organization development and change (2nd ed.) (pp. 193–211). San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Cooperrider, D. L., & Whitney, D. (2007). Appreciative Inquiry: A positive revolution in change. In P. Holman, T. Devane, & S. Cady (Eds.), The change handbook (pp. 73–88). San Franscisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Cranton, P. (2006). Understanding and promoting transformative learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Cranton, P., & Taylor, E. W. (2012). Transformative learning theory: Seeking a more unified theory. In E. W. Taylor & P. Cranton (Eds.), Handbook of transformative learning (pp. 3–20). San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Daloz, L. A. P. (2000). Transformative learning for the common good. In J. Mezirow (Ed.), Learning as transformation (pp. 103–124). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Dirkx, J. M., Mezirow, J., & Cranton, P. (2006). Musings and reflections on the meaning, context and process of transformative learning: A dialogue between John M. Dirkx and Jack Mezirow. Journal of Transformative Education, 4(2), 123–139.

Easton, P., Monkman, K., & Miles, R. (2009). Breaking out of the egg: Methods of transformative learning in rural West Africa. In J. Mezirow & E. W. Taylor (Eds.), Transformative learning in practice (pp. 227–239). San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Seabury.

French, W. L., & Bell, C. H. (1999). Organization development. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Gilpin-Jackson, Y. (2013). Practicing in the grey area between dialogic and diagnostic organization development. Organization Development Practitioner, 45(1), 60–66.

Heifetz, R., Linsky, M., & Grashow, A. (2009). The practice of adaptive leadership. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Hyland-Russell, T., & Groen, J. (2008). Non-traditional adult learners and transformative learning. Paper presented at the 38th Annual Conference of University Teaching and Research in the Education of Adults, July 2–4, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

Johnson-Bailey, J. (2012). Positionality and transformative learning: A tale of inclusion and exclusion. In E. W. Taylor & P. Cranton (Eds.), Handbook of transformative learning (pp. 260–273). San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Lange, E. A. (2004). Transformative and restorative learning: A vital dialectic for sustainable societies. Adult Education Quarterly, 54(2), 121–139.

Lee, S.-Y. D., Weiner, B. J., Harrison, M. I., & Belden, C. M. (2013). Organizational transformation: A systematic review of empirical research in health care and other industries. Medical Care Research & Review, 70(2), 115–142.

Marshak, R. J. (2002). Changing the language of change: How new contexts and concepts are challenging the ways we think and talk about organizational change. Strategic Change, 11(5), 279–282.

Merriam, S. B., Caffarella, R. S., & Baumgartner, L. M. (2007). Learning in adulthood (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (1998). On critical reflection. Adult Education Quarterly, 48(3), 185–198.

Mezirow, J. (2000a). Learning to think like an adult: Core concepts of transformation theory. In J. Mezirow (Ed.), Learning as transformation (pp. 3–34). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (Ed.) (2000b). Learning as transformation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (2009). Transformative learning theory. In J. Mezirow & E. W. Taylor (Eds.), Transformative learning in practice (pp. 18–31). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J., & Taylor, E. W (Eds.) (2009). Transformative learning in practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ntesane, P. G. (2012). Transformative learning theory: A perspective from Africa. In E. W. Taylor & P. Cranton (Eds.), Handbook of transformative learning (pp. 274–288). San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Pearson, C. S. (Ed.) (2012). The transforming leader. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Poter-O’Grady, T., & Malloch, K. (2011). Quantum leadership. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Quinn, R. E. (1996). Deep change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Schein, E. H. (1999). Process consultation revisited. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Taylor, E. W. (2000). Analyzing research on transformative learning theory. In J. Mezirow (Ed.), Learning as transformation (pp. 285–328). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Taylor, E. W. (2009). Fostering transformative learning. In J. Mezirow & E. W. Taylor (Eds.), Transformative learning in practice (pp. 3–17). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Taylor, E. W., & Cranton P. (Eds.) (2012). Handbook of transformative learning. San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Tisdell, E. J., & Tolliver, D. E. (2003). Claiming a sacred face: The role of spirituality and cultural identity in transformative adult higher education. Journal of Transformative Education, 1(4), 368–392.

Weick, K. E., & Quinn, R. E. (1999). Organization change and development. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 361–386.

Zander, R. S., & Zander, B. (2000). Transforming professional and personal life. London, United Kingdom: Penguin Books.