Organizations that empower folks further down the chain or try to get rid of the big hierarchical chains and allow decision making to happen on a more local level end up being more adaptive and resilient because there are more minds involved in the problem.

—Steven Johnson

- In comparison to peers who do not actively engage employees, companies that do, can measure their competitive edge in the form of increased profitability (16 percent), improved productivity (18 percent), higher customer loyalty (12 percent) as well as decreased employee turnover (25 percent), fewer safety incidents (49 percent), and lower absenteeism (37 percent).1

- The annual Sustainability Executive Survey from Green Research finds 88 percent of senior sustainability executives say they plan on investing in increased employee engagement.2

- Since 2008, Intel has calculated every employee’s annual bonus based on the firm’s performance in measures such as product energy efficiency, completion of renewable energy projects, and company reputation for environmental leadership.3 Its market share among semiconductor manufacturers has reached a ten-year high.

To this point, this book has emphasized what are essentially “macro” issues. That is, the focus has been on those higher level issues that involve top management committing resources and setting the overall direction of the firm. These issues involve corporate-wide investments in new tools and training. These are issues involving strategic focus. Implicit to this treatment is the assumption that the macro perspective is enough. That is, once these issues are addressed at this higher level, the rest of the organization will follow and implement the directions established at the macro level. Implicitly, with this approach, we are assuming that these other, more detailed stages have little or no impact on how an organization achieves a sustainable supply chain and that the interaction between the levels is insignificant. Ultimately, these assumptions are both spurious and highly dangerous. To be successful with sustainability, we must in the end succeed at the deployment/implementation stage. To succeed at this stage, we must in the end enable and empower the customers, the suppliers, and the employees who work within the organization; we must also empower the supply chain. Such empowerment is as important as the macro issues. It requires training, scouting, talent development, and, in some cases, significant changes in the organizational culture. Ultimately, such empowerment builds success because each and every person understands the overarching goals and their contribution to these goals. In their actions, taken every day without management overview, the people (be they customers, suppliers, or corporate employees) make the vision of sustainability into reality. How we achieve this state is the focus of this chapter.

Objectives

Building off of Chapter 3, we continue to focus on the organization of the constituent elements of individuals and processes into a coordinated, harmonious whole for the organization, and supply chain. We can also use the terms collaboration and partnership to recognize how integration is already part of commerce. Our ability to synthesize, to break complex relationships down into elemental, core requirements is essential to the integration of sustainability. The ability to look at systems and supply chains in these ways forms the core of this chapter when addressing the human element, and a roadmap to success while finding opportunities to rethink what you and your organization do on a day-to-day basis.

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand the human dynamics involved in a supply chain.

- Explore and understand how the supply chain can be used to create a viable and strong force for sustainability.

- Apply a systematic approach, using Juran’s Universal Breakthrough Sequence, to make sustainability a day-to-day habit.

Integration—The Key to the Sustainable Supply Chains

Critical to the success of the sustainability initiative, as deployed within the supply chain, is the notion of integration, or the manner in which we link the various components that make up the supply chain. Integration is an important term that is frequently found in discussions pertaining to the supply chain. It is also a term that is often used without any definition. Consequently, it is one of the most misunderstood terms in supply chain management.

Integration occurs at various levels: legal, processes, data, systems, information flows, and the extent to which the participants invest in each other’s systems. Integration can be “tight” where the parties work together to ensure that their actions and flows are closely and continuously synchronized. Integration can also be “loose”—where the parties are bound by some set of general agreements over which they will strive to achieve when working together. Integration is important because it influences three critical supply chain traits: visibility, the ease of information flows, and the resulting relationship structure.

Visibility (previously discussed in both Volume 1 (chapter 3) and earlier in this volume) determines how far into the supply chain both upstream (through the supplies) and downstream (customers) you can effectively see. As such, visibility is important because it serves as an early warning system. That is, the greater the visibility, the earlier that the organization can identify a potential problem before it becomes serious. Visibility is akin to your ability to look down the road when driving. The farther down the road that you can see, the earlier that you can identify a change in conditions (e.g., cars slowing down) and take appropriate corrective actions. Visibility gives you the time to evaluate the situation and to consider alternative actions open to you. Without visibility, you are faced by the need to take immediate actions now, often without a lot of evaluation of the situation or the options available. Decisions made without visibility are seldom the best.

Before leaving this discussion, it is important to recognize that visibility is now becoming a corporate and business imperative. There are several reasons for this. First, there is a fundamental change taking place in the marketplace. The new customer is the millennial. These customers, typically born beginning in 1982, are different. They expect sustainability—something that firms such as MillerCoors have found; they are willing to search for such products. They will search the Internet for products that conform to their expectations. They also want to know the origin of any product that they consume. If you cannot provide such visibility, then expect to lose sales and customers.

In addition, thanks to technological advances—specifically the Internet of Things (IoT) and social media (e.g., facebook)—the ability to provide such visibility is getting easier and cheaper. We are finding ourselves living in a world of smart sensors. These sensors, found in smart phones, tags, product identifiers, and packaging, can be used to monitor location and state in real time. The IoT is providing the structure whereby visibility in real time is being created.

The second trait, ease and openness of information flow, refers to how easily and openly information and data flows between the various parties in the supply chain take place. Information flows are important since they help shape expectations and ensure that these expectations are aligned. The ease and openness of information flows contribute to the timeliness of information (i.e., early warning) and the extent to which important information is provided in advance or is made available after the fact.

The third element, relationship, focuses on the structure or governance under which the parties involved in the supply chain relationship work together. Relationships are important because they affect such supply chain traits as:

- Duration of the relationship.

- Obligations of the parties involved.

- Expectations of the parties involved.

- How the parties interact and communicate with each other.

- How planning and the setting of goals across the supply chain takes place.

- Performance measure and analysis.

- Sharing of benefits, costs, and risks.

Relationships can take many forms (transactional/arm’s length versus collaboration and strategic). For the sake of simplicity, we will focus on and compare arm’s length versus collaboration, as summarized in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1 Relationships: A Comparison of Arm’s Length and Collaborative

| Arm’s Length/transactional | Collaborative/Relationship |

Short term (year or less) |

Long term (often exceeding a year) |

Legally defined (often by the contract) |

Based on expectation of mutual benefits and trust |

Limited information sharing |

Extensive information sharing |

Relationship viewed as a zero-sum game |

Relationship viewed as a “win/win” |

Relatively resource light (i.e., does not use an extensive amount of resources) |

Very resource intensive |

Appropriate for commodities |

Appropriate for strategically important products or services |

Alignment of expectations and sharing of information are easier under a collaboration relationship. But, it is also more resource intensive in that the firm has to identify the “right” partner, evaluate the partner, work on building trust and credibility, and then work on maintaining the relationship—all of which requires time, management commitment, and resources.

A second consideration is that of how tightly linked the relationships are. When we talk about tightness, we are talking about such issues as:

- Sharing of information.

- Extent to which information is “pushed” or “pulled”—that is, is information provided without being asked for (i.e., pushed) or is it provided in response to specific requests (pulled through the supply chain)?

- Extent to which the information is symmetrical or asymmetrical.

- Extent to which firms make investments in each other’s systems.

Relationships span a spectrum ranging from a modular system on one end to a unified system on the other. With a modular system, the firm has limited visibility into the supply chain. In most cases, this visibility can be best described as being “one up and one down”—that is, we are integrated with our immediate customers and with our immediate suppliers. Yet, beyond these, we have almost no visibility. Underlying the modular system is the implicit demand that our partners manage the problems beyond our span of attention. That is, the first-tier supplier is responsible for managing any supplier problems occurring below them; similarly, the immediate customers are required to deal with any demand-side problems. This puts a great deal of responsibility on these partners. Modular integration is relatively cost efficient. Yet, it does expose the firm to greater risks because visibility is very limited.

In contrast, there is the unified approach where relationships are being built through the various stages, with the goal of coordinating the activities. This approach gives greater visibility. With visibility, we can see beyond the first tier and identify potential problems before they can affect us. We can intervene and prevent a minor problem from becoming a major one. Yet, this visibility comes at a cost in the form of greater resources and time needed to develop this visibility. The point being raised here is that of trade-offs.

The analysis between these two competing approaches is further complicated by the increasing presence of business analytics. Business analytics is the culmination of three important trends:

- More powerful, lower-cost computers.

- More powerful software packages that are based on advanced mathematics, statistics, and other similar quantitative tools.

- Greater availability of information (also called big data).

The result is that companies such as IBM, L’Oréal, McDonalds, P&G, Unilever, and Walmart to name a few, have implemented analytics aimed at providing firms with greater visibility into their supply chains.

Supply Chain Management’s Integration Opportunity

Despite ongoing attempts to integrate supply chains, many individuals and teams can be overwhelmed by the organization of data required for effective analysis to fully understand sustainability issues and opportunities. The competitive advantage a firm can derive from supply chain integration and optimization is from understanding and leveraging the emerging methods, guidelines, and standards now available to supply chain and sustainability professionals outlined in this book.

Requirements for successful supply chain management integration require communication and trust as information exchange is essential for supply chain members to understand each other, share common goals, and make decisions that are mutually beneficial. As Senge, Lichtenstein, Kaeufer, Bradbury, and Carroll, (2007) found, meeting the challenges of sustainability “writ large” would require not only supply chain integration, but also cross-sector collaboration for which there is no real precedent.4

Additional requirements for successful analysis require supply chain visibility leveraging information systems and data sharing with supply chain members to see into any part of a supply chain to access data on inventory levels, or the status of shipments. This visibility within supply chains is growing more expansive of both social and environmental metrics. These metrics are now included in firm performance and are solicited as part of supplier assessment programs and audits including examples such as Walmart’s 2011 initiative in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2 Walmart’s Supplier Sustainability Assessment: 15 Questions for Suppliers5

Energy and climate: reducing energy costs and Green House Gases (GHG) emissions

|

Material efficiency: reducing waste and enhancing quality

|

Natural resources: producing high-quality, responsibly sourced raw materials

|

People and community: ensuring responsible and ethical production

|

| Source: Walmart Supplier Sustainability Supplier Survey, (2013). Walmart Supplier Sustainability Assessment: 15 Questions for Suppliers, http://az204679.vo.msecnd.net/media/documents/r_3863.pdf |

An important part of any analysis will be performance metrics as they are necessary to confirm whether a supply chain is functioning as planned and help identify opportunities for sustainability and performance improvement. Signaling through the Walmart supplier assessment signals the importance of energy and climate, material efficiencies, and natural resources, along with people and the community. There are a variety of traditional supply chain measures used, including but not limited to reliability, asset utilization, costs, quality, and flexibility. Performance measures and metrics involving sustainability are gaining prominence as stakeholders including supply chain customers are asking for disclosure of social, governance, and environmental information more than any previous time in history. The pressure to measure and disclose provides a proving ground for new and innovative ways to analyze the performance of a firm or a supply chain along multiple dimensions.

The continued global interest in improving business management through the reduction of Greenhouse gas (GHG) is driving sustainability-focused companies and suppliers to measure and manage their carbon footprint. While environmental and social responsibility is predominately voluntary in North America, environmental mandates in regions such as the Europe have a far-reaching impact on manufacturing and logistics in the United States. The proliferation of U.S. corporate acquisitions by European and Far Eastern companies results in the sustainability policies of these parent organizations reaching around the world. In addition, suppliers of both goods and services to the leading edge sustainable organizations are beginning to see the shift from optional GHG improvement initiatives to required sustainability strategies to remain a viable supply chain partner.

Companies today are focused on shareholder and customer values, while maximizing the velocity of information transfer, reduction of waste in the system, and minimizing response time. Supply chain integration involves working across multiple enterprises or companies to remove waste, and shorten the supply chain time in the delivery of goods and services to the consumer or customer. Until recently, supply chain analysis has overlooked opportunities for systems thinking and the ability to include forward-looking strategies for firms and their supply chains involving the primary elements of sustainability, that is, the ethical management of financial, environmental, AND social capital so firms can better measure and manage supply chains with an integrated approach to performance.

Collaboration

Now, we’re seeing firms such as Nestlé take the concept of “shared value” and turn it into genuine, in-depth supplier collaboration. Its work with Golden-Agri Resources on palm oil in Indonesia (a difficult operating environment to get good news stories from) could soon become a model or benchmark for supply chain transparency.

In the equally complicated and low-margin clothing industry, companies such as New Look have done amazing work with suppliers, helping them understand how to run better factories. What have better factory management practices got to do with sustainability? Everything. If you want to cut forced overtime for workers, increase productivity, reduce accidents, increase profits, and lower environmental emissions and impacts—that’s all about sustainability and efficient business practices.

That’s easy to say, but your average stressed shift manager or factory owner doesn’t usually know how sustainable business practices can or should be applied to their workers or business operations. We must remember that most developing-country entrepreneurs and managers didn’t go to business school. They didn’t have much, if any, real training. They saw opportunities, and they made it up as they went along.

That makes them heroes in many ways—for taking risks, creating jobs, and lowering prices. But, the unintended consequences of that created demand have been serious impacts on the environment and human well-being, as we all know. These managers are not bad people. They just didn’t understand how to do business any other way, and most still don’t. Big companies must help them find out, and push them to improve. Resource efficiency, environmental impacts, and the need to hang on to workers have created a pressing business case.

We don’t know of a manager or business owner anywhere who would turn down practical help to become more efficient. Making sustainability stick has to be framed in those terms. Get that right and put the resources into doing in a five-year timescale with annual reporting and measurement, and you’ll be amazed at the results, for both your business, community, and the planet.

It really can be that simple. Invest in processes and practices while measuring the sustainable value added (SVA), and get a massive return on investment.

Sustainable Supply Chain Management Integration

Over the past two decades, there has been an exponentially increasing amount of published research regarding sustainability in both practitioner and academic circles. Authors in the field of supply management have increasingly come to recognize the pivotal role which the supply management professional plays in bringing to fruition an organization’s sustainability vision. Yet, many organizations are overwhelmed by this information and struggle to implement basic sustainability programs.

We turned to the literature to identify trends that both explain the current state of sustainable supply management, as well as highlight positive steps that could be taken to ease this transition.6 We reviewed over 200 of the most pertinent articles taken from both journals and special publications. A summary of this work provides a framework illustrating the internal and external focus necessary in order to successfully achieve the significant benefits of sustainable supply management (see Figure 4.1). To realize these benefits of integrating sustainability, internal sustainability champions will have to: (a) identify and articulate the organization’s drivers, (b) mitigate existing and potential barriers, and (c) embrace the enablers for this process. Within the context of these categories, we next summarize and draw lessons learned from publications spanning almost two decades.

Figure 4.1 Important attributes of supply chain management integration

Drivers are those actions providing motivation for sustainable supply management. The main drivers tend to be external to the organization itself, and most are reactive in nature. The most commonly cited external drivers are: (a) the reactive need for regulatory compliance, (b) proactive considerations to avoid environmental impacts, and (c) reactive replies to customer and competitive pressure.

Not surprisingly, of the drivers internal to the organization, by far the one most commonly cited is that of cost savings. However, it is interesting to note that the next three most prevalent internal drivers are pressure from employees, commitment of the founder, and championing from senior management. This points to the fact that although ideally there is alignment across the organization for the need to implement sustainable sourcing management practices, it is possible to successfully approach this in either top-down or bottom-up fashion.

Barriers are typically anything that restrains or obstructs progress and barriers garnered much attention in the literature. Within this area, the most cited barriers to the implementation of sustainable supply management practices pertain to internal organizational issues including the following:

The presence of competing and incompatible corporate objectives within various supply chain participants. For sustainability to be effective, the various participants must agree that sustainability is critical. This agreement must not only be at a strategic level; but also at a cultural level. There should be a “gut” feeling among everyone in the firm that sustainability is not only strategically and economically the best option, but it is also the “right” option. In a past discussion with Dr. Robert Spekman of the Darden School of Business, the University of Virginia (and one of the research leaders into B2B relationships and collaboration), it was noted that the first and major determinant of the success of a supply chain relationship is that of similarity of corporate cultures. If you see sustainability as critical but your supplier is more interested in cost, then you will not achieve sustainability. The importance of this consistency in culture (especially when dealing with key partners) is so important that it demands that the firm visit these potential partners directly to evaluate their corporate culture and their core values (with special attention being paid to sustainability as part of the core values). As Edgar Schein7 observed, corporate culture cannot be observed and assessed from a distance.

Incentive systems focused on short-term profits. In Volume 1, Chapter 2 of this book series, we focused on Polman and Unilever. What is interesting about Polman’s approach is that he has discouraged the use of quarterly reports. The reason—focusing on such results can divert attention from sustainability to, in most cases, cost. When this occurs, we send confused messages to the rest of the organization and to the supply chain. The message that we send—sustainability is important only as long it does not negatively affect profit. This implicit message communicates to everyone that profit, not sustainability, is the key strategic motivator.

Cultural resistance to change. Corporate culture, as previously noted, is critical. In many cases, when we introduce sustainability, we are effectively introducing a significant shift in strategy. If the firm has been successful with a previous strategy (most often cost based), the corporate culture that develops over time institutionalizes the practices and approaches that made the firm successful with this prior strategies. As the corporate culture is spread through on-the-job socialization, it often creates a force for stability. Such a force is important during periods of change. However, we must recognize that culture can also act as a source of resistance when the change being introduced is both fairly significant and different. Under such conditions, to overcome the resistance offered by corporate culture requires that we must first discredit the current ways of doing things. Unless this is first done, then people will fall back to the patterns of behavior supported by the existing corporate culture. Suffice to say that discrediting the current ways of doing things (especially when the firm has been successful over the long term with these approaches) is not easy to do.

Lack of top management support. Any strategic initiative such as sustainability requires a strong message from the top that: (a) this initiative is important to the firm, (b) the initiative is one that firm is committed to, and (c) you should be prepared to support this initiative or else you leave either voluntarily (through resignation) or involuntarily (through termination). For top management support to be effective, it must be visible to everyone involved, it must be active in nature (where top management is seen as actively involved in the initiative); and it must involve both rewards and punishment. That is, the top management must be ready to reward those who work to support the implementation and attainment of the new objectives. More importantly, the top management must be seen as being prepared to act when there is credible evidence that some people (especially those people who are seen as either opinion leaders or who occupy important positions within the firm) are resisting the new initiative. As a top manager put it to one of the authors, top management must be prepared to carry out a few “public executions” (terminations that become widely known throughout the firm).

Concerns over credibility/consistency. This issue specifically refers to the supply chain. Here, we are looking at a simple issue—it is impossible to credibly ask your support chain partners to do something that you, as a corporation, are not willing to undertake. You cannot ask the supply chain to pursue sustainability initiatives and objectives when your firm is not doing so. McCormick and Company, Unilever, Steelcase, and Herman Miller can ask for sustainability from its supply chain because they themselves are leaders in their industry in pursuing and embracing sustainability internally. They have done internally first that which they then ask of their suppliers.

Supply management not having a strategic role within the organization. Finally, if the supply chain is seen as being strategically decoupled and driven by concerns of reducing price, improving quality, or ensuring on time delivery, then we cannot expect to see the supply chain embrace sustainability. To these partners, sustainability is something that will not affect them because at the end of the day, they are asked to deliver the same outcomes: price, delivery, and quality.

Other commonly cited barriers include: cost, both in terms of time and resources; an acknowledged skills and expertise gap on the part of employees; and issues around measurement and reporting such as the lack of consistent standards and the difficulty in understanding and applying consistent measures. The overarching theme from the literature indicates that sustainable supply management practices will require an organization-wide paradigm shift from established ways of doing business, and that the leaders in this area have already undertaken such a shift.

Enablers supply the means, knowledge, or opportunity for operational sustainable supply chains. This definition is consistent with the use of enablers of reverse logistics;8 supply chain performance measurement system implementation,9 and current research in sustainable supply chains.10 This area of sustainable supply management practices has received the most attention over the years. Important internal enablers for you and your management team to focus on starts with (a) linking sustainability to overall organizational strategy, (b) making supply management a strategic activity within the organization, (c) gaining and maintaining top management support, and (d) adopting a proactive approach together with a long-term perspective toward both the business itself as well as to issues of sustainability.

Important external enablers include opportunities to increase the following to support any sustainability initiative: cooperative, trusting, and transparent communication with suppliers; establishing effective supplier evaluation systems that include both rewards and penalties; using cross-functional teams for collaboration in the areas of innovation and process improvement; and increasing cross-functional education in the area of sustainability.

What are the Benefits of Sustainable Supply Chain Management?

Paradoxically, the benefits of sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) form the fundamental reason for undertaking the sustainability challenge. It is not surprising that in this area both direct and indirect financial benefits garner attention. Overall, the most commonly found benefits include: (a) a reduction of costs, including a product’s whole life costs and the organization’s overall operating costs; (b) increased competitive advantage and differentiation; (c) increased profits; (d) decreased damage to the environment and human health, (e) increased levels of innovation, (f) the potential to gain new customer market segments, and (g) risk mitigation.

Transforming supplier business models is the corporate strategy of the future. Because much of your firm’s impacts are likely to be in your supply chain (there are exceptions), it makes sense to integrate the chain as early as possible. Today, lots of large companies, including 85 percent of the global 250, have or are developing sustainability reports with specific goals and targets. Many even have holistic “plans” with ambitious 2020 and 2050 targets across their business. But for many businesses, making these plans happen and making them have an impact internationally are going to be about sustainable change in how suppliers operate.

Companies that lead the way on sustainability have been pioneering longer-term and more in-depth supplier relationships for years. For them, this is not new. These companies include Nike (technical training for suppliers), Unilever (smallholder farmers), Marks & Spencer (eco factories), and Sainsbury’s (bananas). Cadbury, before being acquired by Kraft, was also developing long-term supplier partnerships with cocoa-producing villages in Ghana. One long-standing approach to sustainability and closing the loop on supplier relations involves the concept of reverse logistics.

Reverse Logistics—Managing Returns of Material through the Supply Chain

For most firms, their responsibility to a product or service is largely defined by their position of title. Title legally defines ownership—when you have title to something, you own that entity. Physical possession is not enough to define ownership (e.g., shoplifting is possession without title and is considered a crime). Responsibility is that state where we are liable to answer for how we manage an asset or activity. In the past, the possession of title was seen as defining ownership. When you had title to a product, you were responsible; when you sold something, you were no longer responsible for it. Today, with sustainability, that is no longer the case.

Firms are now realizing that their responsibility is present in nearly all stages of the product life cycle. However, increasingly managers are looking to the end of product life stage as an opportunity for improving sustainability and fully integrate closed-loop supply chains and a circular economy. Firms are now realizing that by taking better control of returns and products that are being disposed, they can gain certain major advantages, namely,

- Opportunity to learn why products are returned or why they reach the end of their lives. When a product is thrown away or incorrectly returned, the firm has no opportunity to uncover why the product was returned or thrown away. Such information could positively influence product design and quality.

- Opportunity to return useful products back to the market. Customers return products for a number of reasons. By taking control of these products, firms can evaluate them to identify the reasons for the returns. For those products that are still useable, these items can be returned at a discount to the marketplace. For those products that are in need of repair, these can be repaired and returned. In other cases, the products or the components contained within them can be remanufactured and sold/used for other uses such as repairs.

- Opportunity to properly dispose of waste and sensitive material. For those products that must be disposed of, the firm can ensure proper disposal. During this stage, the firm can potentially recycle the raw materials or it can ensure that, if there are any potentially damaging items (i.e., hazardous materials or sensitive data), they are appropriately dealt with. Consequently, the firm can reduce its exposure to end-of-life risks.

- Opportunities to recycle products and/or their components. McDonald’s UK has been able to improve its performance by using the same trucks that delivered products to its stores to collect cardboard for recycling. This approach is not unique to McDonald’s. Companies such as Shaw, Mohawk, and Monsanto are now making carpets from recycled materials. In many cases, old carpets are being converted into new carpets. By capturing these returns, firms are able to prevent these old products from being thrown away in landfills. Product take back and recycling have also been embraced by the electronics industry and by such companies as Acer, Apple, Cisco, Dell, Hewlett-Packard, Lenovo, Mitsubishi, Panasonic, Philips, Samsung, Sharp, Sony, Toshiba, and Vizio. This initiative has also been embraced by retailers such as Best Buy and Target.

These and other considerations have driven firms to consider such initiatives as reverse logistics.

… the process of planning, implementing, and controlling the efficient, cost effective flow of raw materials, in-process inventory, finished goods and related information from the point of consumption to the point of origin for the purpose of recapturing value or proper disposal. More precisely, reverse logistics is the process of moving goods from their typical final destination for the purpose of capturing value, or proper disposal. Remanufacturing and refurbishing activities also may be included in the definition of reverse logistics.11

The successful implementation of such initiatives requires the active involvement of the supply chain. In some cases, the firm can outsource the recovery activities to other firms that are experts in this area. In other cases, the firm must depend on the stores to help in the returns and must work with its supplier to ensure proper disposal of the returned product.

Putting Sustainability into Practice

We know business sustainability works best when cross-functional teams and entire supply chains are involved and enabled. Sustainability is here to stay, and the supply management group is a significant player in any organization’s success in this arena. Based on our review of published research and our own insight from working with companies integrating sustainability, we recommend that you take the following steps in order to reap the benefits of sustainability-based supply management:

- Identify and engage your internal champions of sustainability at whatever level of the organization they may be.

- Conduct a self-audit to identify the primary drives in support of sustainability initiatives within your organization.

- Scrutinize and create a plan to mitigate or overcome the barriers you will encounter.

- Research, operationalize, and maximize the available enablers while recognizing the need for employee engagement.

Employee Engagement

We have always measured processes and practices, but we still do not fully understand metrics and engagement. Juran and others over time have repeatedly told us that the greater the level of detail we go to for in a process, the better we understand and can manage for efficiency and effectiveness. To this end, many companies are changing internal practices to align with sustainability.

Intel has been pushed by investors for years to address issues of say-on-pay, the human right to water, and sustainability as part of a board’s fiduciary obligation. So, it’s not surprising that Intel links employee compensation to sustainability results. What is surprising is that Intel is doing this for its entire workforce. Since 2008, every single employee’s annual bonus is calculated on the basis of the firm’s performance on measures like product energy efficiency, completion of renewable energy and clean energy projects, and the company’s reputation for environmental leadership. Last year, Intel added into the equation performance on reducing the company’s carbon footprint. This is a smart move that will empower employees up and down the organization to find reductions big and small.

National Grid is an energy management and delivery company focusing on meeting the needs of customers in Massachusetts, New York, and Rhode Island. Its compensation model shows how to embed sustainability practices into a company’s DNA. In talking with company president Tom King recently, we asked how he knows that sustainability is really being addressed in his company. His instant response was that it’s part of everyday conversation at National Grid, and that there are no executive meetings that don’t touch on environmental performance. Like Intel, National Grid has tied CEO and other executive compensation to performance on the company’s GHG reduction goals. But, what’s most interesting here is how aggressive those goals are: an 80 percent reduction by 2050, with 45 percent by 2020. That’s a lot of executive pay at stake—and this from a major electric power utility.

All of these examples help to highlight the level of detail necessary to understand processes and the importance of engagement. To next look at a roadmap for understanding a proven approach to problem solving, we again turn to Juran and one of his well-known processes.

A Proven Approach to Integrating Problem Solving

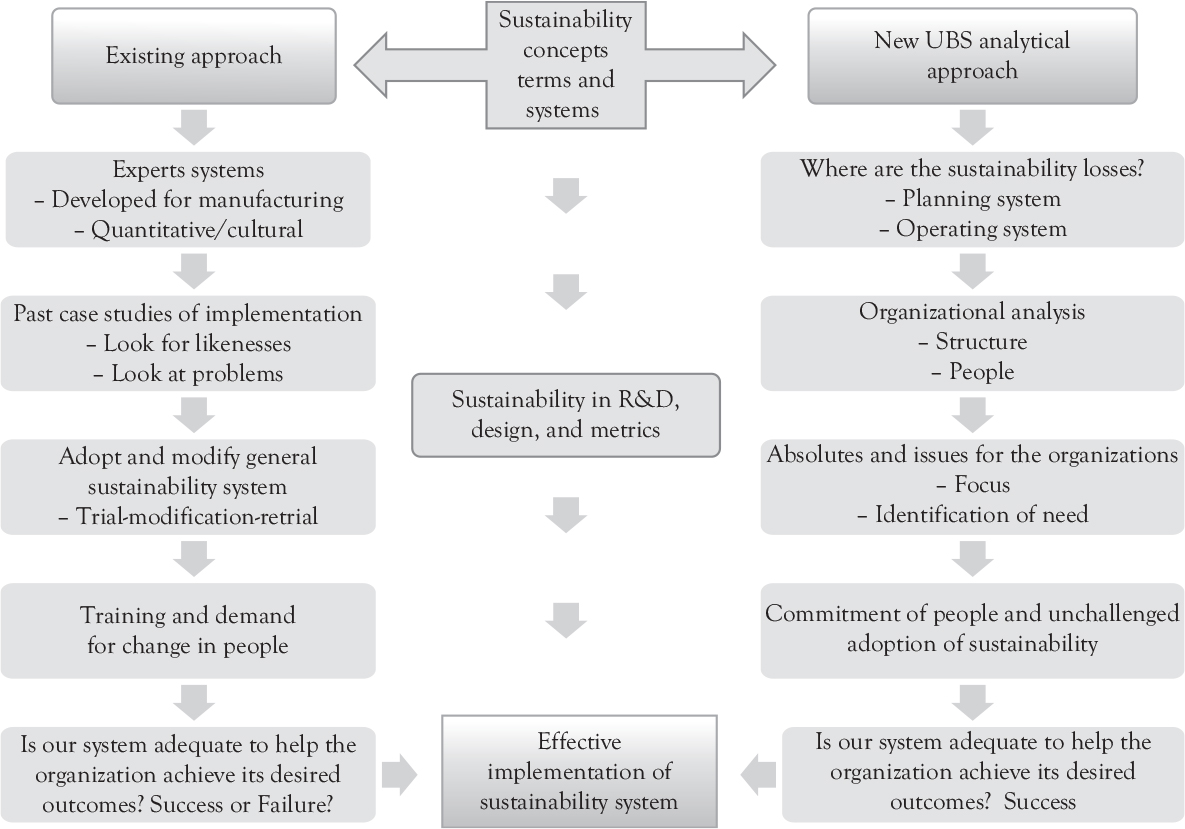

Juran is well known for developing a systematic approach to total quality management (TQM). His goal, in developing this approach, was to make quality into a habit. For quality to become a habit, it had to be the result of a repeatable process. This process was termed the Universal Breakthrough Sequence (UBS). This logic applies equally well to sustainability as a focal point as it applies to the proven benefits of TQM.

The very first step in this process is the creation of an awareness of need for a change. Without this awareness, people and organizations would not change. After all, a person changes when faced with compelling evidence that the current ways of doing things were no longer succeeding. The way to create this awareness is through a self-audit (Figure 4.2). Such a self-audit helps show the participant where they are doing a good job and those areas in which they are encountering problems. It enables the participant to answer a simple but critical question: Is our system (or are our current practices) adequate to help the organization achieve its desired outcomes (and, if not, where are the changes most needed)?

Figure 4.2 Modified UBS approach to make sustainability a habit

Without such an audit, no change is possible because you have not shown the person or the organization that the current systems or practices are no longer sufficient. Consequently, no change will take place because no compelling reason for change has been provided.

Juran defines breakthrough as “the organized creation of beneficial change” and has observed that all breakthrough follows a universal pattern:

Proof of the need: Draw attention to the “heavy losses” incurred by companies not effectively managing the systems they are charged with leading. Show the “dangers of managing by visible figures alone” and that “the most important figures for management are the unknown and unknowable.” Sustainability remains so elusive to many managers that this “unknown” performance opportunity may be the key to unlock the performance measurement revolution. The question sustainability invokes is how to draw manager’s attention to a sustainability project when they are so busy living with “business as usual” that they have learned to endure the levels of chronic waste? Juran suggests using quick estimating approaches to assess the costs of waste with the aim to “bring chronic troubles out of their hiding places and convert them to alarm signals.”

Yet, central to this overall sequence is proof of need. Critical to audits are metrics. Metrics are not simply used for control; they also facilitate communication. When we measure something, we strongly indicate to everyone that what we are measuring is important; conversely, the act of not measuring something indicates that the issue is not important (purposeful communication). Metrics facilitate communication between four stakeholders:

- Top management

- Subordinates

- Customers

- Suppliers

Project identification: Use Pareto principles to find the sustainability opportunities that will have the greatest impact. Separate the vital few projects from the useful many. To help do this, understand the differences between symptoms of problems and finding underlying problems. The vital few are interdepartmental and can have multifirm performance metrics that become the responsibility of management. A starting place for where to find opportunities comes from the key metrics outlined earlier in this chapter within the section on the rise and current state of SSCM (energy efficiency, GHG emissions, water consumption, solid waste, product attributes, environmental exposure, benchmarking sustainability indices, and indexing carbon to products and revenue) as these metrics and associated projects are already used by successful multinational companies recognized as leaders in sustainable practices.

Organization to guide each project: Establish a sustainability team to take responsibility for nominating projects, assigning teams, providing resources, assessment of progress, dissemination of results, and to revise merit systems to include sustainability improvement. Simultaneously, upper management must serve on the team, approve strategic goals, allocate resources, review progress, give recognition, serve on some project teams, and revise the merit system accordingly.

Diagnosis—breakthrough in knowledge: For analysis of symptoms, formulate theories as to the causes of the symptoms, test the theories. Remedial action on the findings: When seeking remedies, choose alternatives, take remedial actions, then deal with resistance to change, and then establish controls to hold the gains. New metrics should be the basis of a business case for a project, align with the business model, and include sustainability. Metrics consist of measures, standards, and consequences. Metrics can be measures at the end of a process. The measure represents the numbers, while the overall metric provides an opportunity for understanding and managing which leads to auditable consequences. Metrics become the basis for constructing a business case around a program or process and, when we drill down deep enough, become the basis for providing a business case behind an initiative. Keep in mind, in a world of no mirrors and no scales; we are all thin and beautiful. We need metrics to help us manage and make decisions that align with our chosen business model and integrated sustainability initiatives.

Breakthrough in cultural resistance: Getting people to change deeply held beliefs is difficult. Take for example Juran, who uses the story of the Earth-centered believers of the 14th century. The believers rejected the logical argument of the astronomers that the Earth revolved around the Sun, partly because they could see the Sun revolving around the Earth. The idea that the Earth was the center of the Universe had come down from revered religious teachers. In the light of such evidence the old beliefs could not be rejected—it was easier to burn the astronomers! Juran recommends providing participation, starting small, providing enough time, work with the recognized leadership, and dealing directly with the resistance.

Control at the new level: Continuously improve, change, and adapt to new opportunities through understanding systems and the interconnected process linking supply chains and value chains.

Paradoxically simple, yet deeply difficult, this approach to continuous improvement and the integration of sustainability into supply chain management provides a roadmap for any new program rollout or project.

Never tell people how to do things. Tell them what to do and they will surprise you with their ingenuity.

—General George Smith Patton, Jr.

Summary

The people and customers up and down a supply chain impact the success of new initiatives. Understanding relationships and the need to collaborate for success underscores SSCM opportunities. For those already integrating sustainability and supply chain partners there are known benefits of cost reduction, operational benefits, competitive advantage, decreased damage to the environment and human health, and increased innovation to name a few. Transforming supplier business models and supply chains is the corporate strategy of the future.

To be successful with sustainability requires that management become involved in supply chain management. This involvement can take several different forms:

- Collaboration.

- Assessment.

- Reverse logistics and circular economies.

- Employee engagement.

- Use of proven approaches such as the UBS.

For any organization to receive the full benefits of sustainability, it must have an integrated approach to SSCM.

Applied Learning: Action Items (AIs)—Steps you can take to apply the learning from this chapter

After reviewing this chapter, you should be prepared to assess internal and external supply chain integration opportunities. To aid you in this assessment, please consider the following questions:

AI: What kind of relationships do you have with members of your supply chain?

AI: How would the UBS help integrate sustainability into your operations and supply chain?

AI: How will you know when you have a sustainable supply chain?

AI: What is your perception of the amount of integration within your existing supply chain?

AI: In what ways have customers asked your organization for social or environmental information within request for quotation (RFQ) or request for proposals (RFPs)?

Further Readings

Elkington, J., & Branson, R. (2014). The Breakthrough Challenge: 10 Ways to Connect Today’s Profits with Tomorrow’s Bottom Line, Jossey-Bass.

Mohin, T. (2012). Changing business from the Inside out. Sheffield, UK: Greenleaf Press.

Senge, P.M., Lichtenstein, B., Kaeufer, K., Bradbury, H., Carroll, J.S. (2007). Collaborating for systemic change. Sloan Management Review. 48(2): 44–53.

Stringer, L. (2009). The green workplace-sustainable strategies that benefit employees, the environment, and the bottom line. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

1Gallop (2009).

2Green Research (2012).

3Lubber (2010).

4Senge et al. (2007).

5Walmart Supplier Sustainability Supplier Survey (2013).

6Nirenburg and Sroufe (2012).

7Schein (1993).

8Ravi and Shankar (2005).

9Charan et al. (2008).

10Grzybowska (2012), Chapter 2.

11Hawks (2006).