Overcoming Organizational Challenges

I am just a child who has never grown up. I still keep asking these “how” and “why” questions. Occasionally, I find an answer.

—Stephen Hawking

Chapter Highlights

• Top five reasons why most organizations fail with OKRs

• Interactions between OKRs and cultures of safety

• The approach to achieving big results

• Challenges with strategy execution

• How not to use OKRs

• Scope of change—how to introduce OKRs

Not so long ago, a large Fintech company approached me to help them grow their customer base by 300 percent over the next two years. This was part of their core strategy to gain more market share and attract investors.

They decided to use OKRs to execute their ambitious strategy. The executive team did an amazing job by defining a handful of company OKRs. But after some months, their OKRs didn’t make the expected impact on their customer numbers. The expected growth results remained elusive. They considered about abandoning OKRs altogether.

Fortunately, they decided to collaborate with me to give OKRs a second chance. They still believed in the potential power of them.

My strategy consisted of helping them to reduce their initial set of company OKRs to just one, explaining to them the concepts of behavior change strategies and how Lean OKRs can play a big role in this. These eye-opening concepts, which I’ll explain in this chapter, really resonated with them. By focusing on a single OKR per cycle, they were given another chance to achieve their growth numbers. To keep everybody engaged and committed, we installed the OKR cycle for all of their teams.

After only one OKR cycle (90 days), their most critical needle already started to move and customer numbers went up. They had overcome the number one enemy of OKRs: “business as usual.”

Why Most Organizations Fail With OKRs

I’ve been lucky to meet many company CEOs who have been open enough to share their OKRs and their systems with me. As good as OKRs sound on paper, a lot of companies struggle to implement them. Applying OKRs takes time, discipline, and hard work. There is no magic formula that helps you implement them.

What I noticed after almost a decade of working with OKRs in all kinds of companies around the world is that there are some common patterns in all failing OKR implementations. There are five main reasons why OKR implementations fail 95 percent of the time:

1. The organization is based on a command-and-control model and doesn’t have empowered (product) teams.

2. Leaders fail to communicate why they want to use OKRs.

3. The OKRs are poorly written and set the wrong goals.

4. Lack of focus, because there are too many OKRs.

5. People get discouraged and disengage due to a lack of visible results.

There are also secondary challenges that organizations might experience and reasons why OKR implementations fail:

• People quit before they see any benefits (OKRs take time and patience).

• People set and forget the OKRs.

• OKRs start as an initiative in a department without support from the executive team (often initiated by HR).

• People don’t know how to move the needle on the KRs.

• People don’t know how to scale OKRs.

• Fear of experimentation (see Chapter 12 experiments).

• Lack of leadership support.

• Companies don’t have true cross-functional or product teams.

• OKRs linked to compensation and bonuses cause sandbagging and anxiety.

• Low psychological safety (we don’t trust people to set the right OKRs).

Most of these challenges are related to the aforementioned five main reasons, so let’s look at them and discover why OKRs might fail in your organization.

Reason 1: Command-and-Control Model

By far the biggest reason why OKRs fail is due to a command-and-control organizational model (often associated with Taylorism), rather than a mission-command model. In a command-and-control model, leaders dictate the rules by providing teams with solutions to implement, rather than inspiring teams to work towards certain outcomes by allowing them to solve problems. Some typical signs that you work in a command-and-control environment are as follows:

• Publicity or vanity-driven metrics influence business decisions (Willis 2012).

• Yearly employee ranking systems (Willis 2012).

• Measurement systems ignore variation and process control (Willis 2012).

• Strategic information is hidden for most employees. Financial numbers such as ARR/MMR, EBIT, and customer churn rate are not made transparent.

• The primary measure of success is delivered features, not achieved outcomes. When product features are not used, they don’t get removed. Labor investments are rarely discarded in light of data and learning. Often, the team lacks the prerequisite safety to admit misfires (Cutler 2016).

• A culture of handoffs. There is a front-loaded process in place to “get ahead of the work” so that items are “ready for engineering.” The team is not directly involved in research, problem exploration, or experimentation and validation. Once the product is shipped, the team has little contact with support, customer success, and sales (Cutler 2016).

• The presence of “project” or “feature” teams.

• The roadmaps consist of a list of features which are shipped without measuring their impact. For example, feature or project teams work on tasks assigned by their managers, giving them little room to use their skills and creativity.

• Engineers are afraid to run rapid experimentation loops on production systems. Software products are not instrumented with tools to measure business results.

• Direct contact with customers is discouraged. There is a “proxy” person who often can only transmit part of the information that teams need to make good decisions.

• You are still struggling to get Scrum to work or try to “scale” Agile with frameworks such as LeSS and SAFe.

For OKRs to work well, instead you need a mission-command organization, where leaders share information transparently and bring Objectives (problems to solve or “jobs to be done”) to empowered, stable long-term teams. This is a model that entices strong leaders to hire great people and then coach them to help them solve complex problems. Leaders should trust and empower their teams to achieve results. These empowered teams are then able to solve problems and can be held accountable for their results (Cagan and Jones 2020, 4). This number one reason why OKRs fail will be addressed more deeply in the second part of this chapter and will be dealt with in relation to different aspects throughout the book. Especially important is Chapter 6, where I discuss how you, as a leader, can empower and trust your teams. Although most leaders would agree with these ideas, many (especially in top management) still find it hard to see how this can work in practice. OKRs work only in an environment where you have true cross-functional and empowered teams. If you haven’t created these conditions in your organization, then OKRs are likely to fail. However, OKRs can also be the catalyst to set such an organizational culture in motion, and this will be explained later in this chapter.

Reason 2: Why, Why, Why?

What specific business problem do you want to solve with OKRs? As we saw in Chapter 1, alignment and focus aren’t the right answers here. You want to take on OKRs to achieve something. Can you articulate and communicate this to your entire workforce? You should. Why OKRs? Why now? Why not? What pain does it solve for you and your employees? What big, hairy, audacious goal does it work toward? Have you looked at any alternatives? As with any change initiative within your organization, you must have answers to these questions. If you fail at this, OKRs are doomed to begin with. In this chapter, I provide you with information to determine where and when OKRs are the right choice.

Reason 3: Perfect Is the Enemy of Good

The best is the enemy of the good.

—Voltaire

When people start with OKRs, it can sometimes be confusing. What makes a good Objective? What do we look at in a KR? People can become really religious about this. Here, the general advice of “perfect is the enemy of good” applies. OKRs are a learning experience that encourages you to stretch what you think is achievable or possible. That means you will constantly improve the OKR system to suit your needs. You will discover how to do this in detail through the OKR Cycle in Part 2. However, there are some important guidelines you probably want to use. For example, an Objective needs to inspire people. How are you going to do this with just words?

Secondly, OKRs are about measuring and tracking progress toward your Objective. Measuring progress and performance can be very hard. How do we define good metrics? How do we collect data? What strategies should be used to interpret the data? How do we measure intangible things like behavior? How do we check in on our OKRs on a weekly basis and see progress? In Chapter 3, you will learn how to create (not perfect but good) OKRs. Good OKRs are a strong prerequisite to achieve big goals.

Over to You

In Chapter 1, you took a shot at writing some Objectives. Be honest, do they sound inspiring to you? Can you adjust or change them so that they could ignite that spark in your team?

Reason 4: A Lack of Focus

Peter Drucker wrote that innovation requires knowledge, ingenuity, and above all else, focus. OKRs help with focus, but only if you have the discipline to focus on one, or a maximum of two OKRs, at a time. Leaders and their teams easily get distracted by their business as usual (BAU) and (urgent) work, thus failing to work on important strategic goals. As they fight a constant battle between keeping the lights on and trying to move forward with their strategy, the BAU work will almost always gain prominence, stealing the focus away from stategic initiatives. With Lean OKRs, you will have the tools in place to win this battle.

Many organizations that make the decision to start with OKRs make the same mistake: They create too many OKRs at the executive level. Often, this is because they try to capture all the work (strategic and operational) into OKRs, which then cascade throughout the organization. When you follow this approach, you will end up with hundreds of OKRs throughout the organization. There is a well-known management consulting firm (I won’t name names) that is still sending out junior consultants who advise that you should execute all your initiatives by only using OKRs. In my view, this is very disadvantageous, and in this chapter, I will outline in detail where and when OKRs should not be used. Lean OKRs are about creating less goals, the minimal amount of goals that are necessary to make the biggest impact for your organization. In Chapter 5, I’ll dive deeper into the essence of the concept of Lean OKRs, the idea behind selecting a single OKR to rule them all.

Reason 5: Lack of Visible Results

Companies start with OKRs with good intentions and motivations. At the beginning of the year, OKRs for the year and quarter are formulated. For each Objective, perhaps there will be three or four KRs. Then, at the end of the first quarter, management or teams begin to notice that very little or nothing has yet been accomplished. They are left scratching their heads and wondering what went wrong. They might continue along this path for another quarter, but most probably, they will abandon OKRs and switch back to the status quo, all before reviewing the KRs and analyzing if they consisted of strong, appropriate indicators to measure the needle moving. It takes at least five quarters to start getting the hang of OKRs and their Cycle.

I can’t blame management teams if they decide to no longer use OKRs. It is a logical response to the well-meant implementation of a system designed to keep us on track and accountable, but (similar to the gym) without discipline and seeing some motivating results, the desire to continue diminishes among the firefighting of BAU and instead is seen as just a waste of time. So, how can we get back on track? To keep people engaged, you need the data, measures, and a dashboard that are worth looking at, something we will look into in more detail in Chapter 13.

When and Where Are OKRs the Right Choice?

In recent years, OKRs have also gotten traction in other fields like personal development and product management. They are thus widely applicable. In this book, I focus on outlining the contexts in which using OKRs makes sense when you are in business.

OKRs evolved from MBOs, which are a tool to execute strategy. Therefore, OKR’s primary purpose is too to execute your strategy, also known as strategy deployment. If your strategy is about how to achieve 10× growth, you need to think out of the box, innovate, take bold steps, and learn as fast as possible from your customers. By growth, I don’t necessarily mean monetary growth. It can be growth of customers, intellectual property, human capital, and so on.

OKRs help execute your strategy to achieve this huge growth surge and help to simultaneously communicate your goals throughout the organization by making them transparent. They enable everyone close to your customers to make decisions based on what best aligns with the organization’s strategic goals. So, OKRs can be applied when you want to execute an ambitious strategy, and as you will see below, they are especially suitable to drive innovation through behavior changes.

Culture Change

Human capital, your resources, or “people” as I like to call them, are the most valuable asset of your company. They’ve also created your “company culture,” which is a set of behaviors typical for your company. Some attribute Peter Drucker to have said: “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” In fact, research has proven that there is a link between culture and outcomes: “When aligned with strategy and leadership, a strong culture drives positive organizational outcomes” (Groysberg, et al. 2018, 44–52). I can only confirm that having the right company culture is critical for achieving OKRs (outcomes). As I explained, the first reason why OKRs fail is because of the command-and-control model, which, unfortunately, is still used by many organizations today.

However, OKRs can also be used as a vehicle to drive the right culture change. When brave leaders of an organization that is leaning toward a command-and-control model start implementing OKRs, they are not entirely doomed. There are a few examples of companies that completely transformed their way of working in just a few years, effectively changing company culture, through the use of OKRs. One is the ING Bank in the Netherlands, which managed to transform its entire company to an Agile organization by successfully employing OKRs to overcome its main challenges, successfully shifting power from the top, getting buy-in from stakeholders, and changing employees’ views about professional development (Birkinshaw 2017). This success was due to strong and visionary leaders at the top and caused a revolution in the enterprise world, both in organization modeling and ideas about company culture. I joined ING Bank after their transformation, and the result was remarkable: True cross-functional teams worked on complex customer problems. Of course, the transformation is never finished, but I was happy to see their efforts paying off. OKRs can thus be used to change the company culture, even when they are implemented with care in a command-and-control model. The organization will then change toward that of a mission-command model with the accompanying more generative culture, in which risk taking is encouraged and all have a stake in bringing the company to the next level.

There are several interrelated cultural factors that enhance the successful implementation of OKRs, and when OKRs are used, these cultural factors are further strengthened. Firstly, OKRs require transparency. OKRs require leaders and teams to be transparent about their goals by announcing them publicly, in turn fostering a more transparent way of working throughout the organization.

Secondly, OKRs are associated with a culture of transformation, because they require as well new ways of working, and to achieve this, people need to change their habits and behaviors. These behavior changes start with the executive team. Can these leaders let go of their control and shift their power to teams? Do they trust their teams, and if not, can they free up their precious time to actively coach their teams so trust can be established?

Thirdly, OKRs require and produce alignment. To move the needle of the company OKRs, leaders and their teams need to work collaboratively with other teams. Without alignment of your OKRs, you will keep organization silos intact and achieve only modest cooperation. My Lean approach to OKRs aligns all leaders, departments, and teams around one common goal, one company OKR, or one product OKR, which will set up teams for cross-department collaboration, giving them broad access to information. As a result, they will be encouraged to experiment and take risks in a physiologically safe environment and will be inclined to share their experiences openly because they are now all “in it together.” In Chapter 8, we look at which different alignment strategies can be used in more detail and how the OKR alignment workshop facilitates and strengthens collaborative processes.

Finally, experimentation is required and failed experiments are inevitable (Kohavi and Thomke 2017). Experimentation is thus embedded within the process of OKRs and therefore will thrive if leaders provide teams the autonomy and safety to do so, fostering a culture where failure leads not to condemnation but to inquiry.

The fact that you enroll OKRs and the OKR cycle can thus help to change the mindsets of many, catalyzing changes toward a generative culture. As part of this culture change, OKRs can simultaneously be used strategically to build new empowered team topologies, although this requires careful timing and active involvement of senior management. One caveat with culture change is that you need to pay attention to emotional management too, which we touch upon later in this chapter.

Team Effectiveness

OKRs help to focus on structure and clarity, provide meaning and purpose, and let you see your impact on the bigger picture. They contribute to what Google found to be the five pillars of high-performance teams (Duhigg 2016). Psychological safety is by far the most important pillar and prerequisite. OKRs also play an important role to support the other pillars, like dependability, structure and clarity, meaning, and seeing impact.

For me, the striking similarity between these found five pillars of highly successful teams and the philosophy, and practice of OKRs was a great eye opener, and kindled my motivation to fully adopt them. When used properly, OKRs can make a significant change in how teams perform. For many companies, this can lead them to achieve the breakthrough goal they need to get closer to their vision and mission. In Chapter 6, we will explore how OKRs can help to charter effective teams.

Innovation

Peter Drucker is famously quoted as saying: “Because the purpose of business is to create a customer, the business enterprise has two—and only two—basic functions: marketing and innovation. Marketing and innovation produce results; all the rest are costs” (Drucker 1977, 90).

Keeping that in mind, how many of you have sat through C-level meetings where their priorities are finances, sales, production, legal issues, and (finally) people. Typically missing from their list of concerns is marketing and innovation. Exactly the two areas that Drucker argues are the only two that matter. Take a moment to close your eyes and imagine companies that focus on constant innovation and then the marketing of their products (and their story). Compare that against companies that you know are floundering. It’s not a stretch to see that if they would be able to shift their focus to those two key areas, there could be light at the end of the tunnel for them.

Innovation brings more customers (or as Seth Godin likes to put it: better customers) and better results (Godin 2018). Sounds easy right? Just set very ambitious goals: “Travel to Mars within 20 seconds” and innovation will happen. I wish it was that easy. Innovation requires trust, agility, the ability to try and fail, and to learn from failures.

Innovation is not about technology nor about implementing the latest organizational models. I always giggle a bit when companies adopt an organization model from a completely different type of business (e.g., banks that adopted the “Spotify organization model”). Unfortunately, many leaders still believe they can take shortcuts to innovation: by starting accelerators, business incubators, research and development hubs, hiring innovation consultants, acquiring start-ups, or blindly adopting the latest digital technologies. I propose a strategy toward innovation that hinges on bringing complex problems to cross-functional (product) teams that will find unique and creative solutions to these problems. That requires teams to generate insights and then to run considerable numbers of experiments to find the right solution for the problem. As Marty Cagan said: “Innovation is the function of the number of experiments we can run” (Cagan 2019). As a great measure for innovation, I very much like the idea to “measure the percentage of revenue that was coming from products and services introduced in the past few years” (Cagan 2011). This metric will almost always force leaders to completely rethink their revenue models every couple of years and help them to come up with great innovative products.

Is your organization ready to experiment, cannibalize stale business practices, or suspend today’s distribution model? What can you achieve within your constraints (time, costs, and scope)? The higher the goal temperature, the more innovation it requires to reach those goals. This leads to demands on both people and processes:

• People: Innovation requires you to have diverse people with a growth mindset in your organization, willing to solve complex problems. For example, MIT’s Mediated Matter research group, headed by Professor Neri Oxman, is using a diverse group of artists, biochemists, and engineers to solve climate problems (Green 2018).

• Process: How fast can we learn from our market, customers, and other stakeholders. If you cannot experiment and learn faster than your competitors, you will be out of business soon. Hence, the “disrupters,” small technology companies that learn and experiment at high speed.

Finally, behavior is where people and processes come together. If you want to generate significant positive cash flow, what kind of human (customer or employee) behavior is required to achieve that goal? Can you measure that? If you want to reduce customer churn, the desired behavior might be that your employees will greet customers in a different way. Or maybe, it’s that you need to offer them better products or services or limit choices to increase quality. Depending on your goal, you might want to think about different ways people must behave in order to meet your goals. In other words, what behavioral innovation is required? What skills and competencies are required?

Operational Excellence

When a company starts with OKRs, there will most likely be many obstacles to overcome before the true power of OKRs can reveal itself. One of these is the need for operational excellence teams, preferably all equipped with a Lean or Agile mindset. Many companies starting with OKRs use them as an opportunity to clean house. They change their internal processes to prepare for the big change to come. During the first few OKR cycles, leaders use the momentum of OKRs to focus on process improvements or even innovations. Teams need a high level of operational excellence before they can start working on complex business problems. OKRs can help you challenge the whole organization to think about how the company should be structured and how processes could be improved. I always enjoy seeing hidden process constraints unfolded and solved when leaders set goals beyond what they thought was possible. When OKRs reveal these constraints, people can use the techniques described in Part 3 of this book to remove them.

OKRs as Strategy Communicators

The key to creating an organization that can innovate at scale is that it enables frontline workers, who solve customers’ problems on a daily basis to make the best decisions possible, aligned with the overall company strategy. The authors of Lean Enterprise wrote: “To achieve this, we rely on people being able to make local decisions that are sound at a strategic level—which in turn relies critically on the flow of information, including feedback loops” (Humble et al. 2015, 9). However, to align people with the company strategy, to let information flow, to develop and let OKRs function, people need to understand what the underlying strategy is.

Research has found that “on average, 95% of a company’s employees are unaware of, or do not understand, its strategy” (Kaplan and Norton 2005, 72–80), and that “one-third of the leaders charged with implementing the company’s strategy could not list even one [strategic initiative]” (Sull et al. 2018). As a result, the following points are true of too many organizations (you may recognize a few):

• The Organizational Health Index (OHI) or similar employee survey results indicate a lack of clear direction.

• Employees say they lack clarity and focus, and they don’t know where the company is going.

• The motivation of the employees is lagging due to a lack of purpose.

• There is little to or no innovation or learning initiatives going on.

• Repeated change initiatives fail.

• Too many constantly changing high priority projects distract people from the overall strategy.

• There are too many ad hoc issues and there’s too much firefighting.

This list goes on and on. Now, if you think OKRs will solve all these problems overnight, I need to warn you. Even with OKRs, you can still have all the issues described earlier. However, when implemented with the guidelines provided in this book, you can eliminate most of them. I will show you how you can use OKRs as a great vehicle to communicate some of your company’s strategic Objectives in a simple, compact way.

Surrogation

OKRs are never a replacement for solid strategy planning (and I dare say strong leadership and communication skills). It’s just easier to communicate OKRs than a 100-page strategic plan. But remember that OKRs are only part of that plan. The HBR article “Don’t Let Metrics Undermine Your Business” (Harris and Tayler 2019) expands on the concept of surrogation in corporate contexts, focusing on the tendency people have to mentally replace a strategy (or vision for that matter) with metrics. Make sure you don’t make this mistake by “replacing” your strategy with just OKRs (and their cousin KPIs).

Focusing OKRs on Behavior Changes

Now that you know in which company contexts OKRs are the right choice, we will further specify how and where you should apply them. The processes, attitude, and culture changes that are required to revolutionize the execution of your company strategy often can only be achieved when people (customers, employees, your teammates, citizens, and so on.) change their behavior. A study by consulting firm Bain and Company (Litré et al. 2018) analyzed barriers to successful change management at 184 global companies and found that when executing strategic plans, a stunning “65% of initiatives required significant behavioral change on the part of front-line employees—something that managers often fail to consider.” While I was researching this topic, a new world opened up for me. If you read between the lines of all books on building a successful business, you will discover a pattern. The one idea that stands out the most is behavior change. However, these are often not easy to administer.

Take the following example: At the time of writing, we are in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, and the strategy in my country to fight the virus is called a “smart lockdown.” To succeed with this strategy, the government requires people to change their behavior by keeping 1.5 meters distance and wearing protective masks in public places. It’s critical to change behavior of citizens, because the political leaders do not have the capacity to observe and control every act of these citizens. However, if the strategy is only addressed occasionally, it won’t have as big an effect as a change in overall behavior, which is a shift at the basic or ground level, addressing something at the roots. Without true behavioral changes, the whole strategy to keep the virus contained will fail. Thus, behavior change is by far the most difficult component of any strategy execution, but also one of the most powerful, and should therefore be the main focus of OKRs.

To really leverage the power of OKRs, you need to carefully look at your current company strategy and ask: How can we use OKRs as a lever to execute our behavior change strategy? With which strategic Objectives do we really need a change in human behavior (both in employees and customers)? In which area do we need significant improvement? When this has become clear, you ask: Does it require a change in human behavior to get us to the desired result? If the answer to the final question is yes, then you know you should be developing OKRs in this space.

Distinguishing Behavior and Sign-and-Go Strategies

To gauge if a specific strategy or initiative requires behavior changes, I have developed a simple division that is inspired by The 4 Disciplines of Execution (McChesney et al. 2012), also known as 4DX. I’m a great fan of this set of proven practices aiming to execute your most important strategic initiatives. The concepts from 4DX and OKRs are quite similar, and I adapted some of the elements of 4DX to improve and streamline applied results of OKRs.

According to the 4DX approach, you can breakup strategies or initiatives that significantly move the needle for you team or organization into two categories:

• Sign-and-go strategies as I like to call them (in 4DX they are called stroke-of-the-pen). If you have the mandate and budget, place your signature at the bottom a document to get the ball rolling: a major acquisition, adding new employees, buying a new software tool, a new marketing campaign, or approving a project. The strategies will contribute to the growth of your companies, but won’t (immediately) require a behavior change.

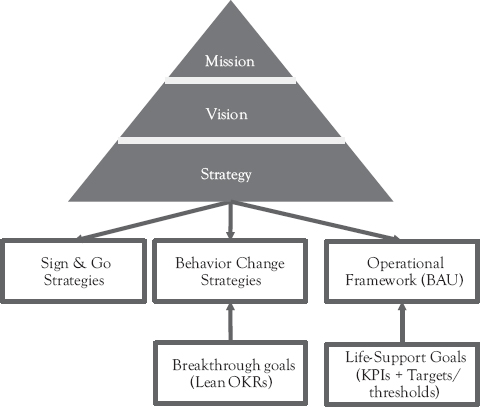

• Behavior change strategies are different, because they require people to change their behavior and habits. You cannot order your customers to use your product differently or to invite their friends to use your service. You cannot order your employees to do something different they have never done before. You probably know how hard it is to let people change their way of working (Figure 2.1).

This distinction is not absolute. For example, sometimes it can happen that a sign-and-go strategy evolves into a behavior change strategy. If you are a company building bookkeeping software and you want to change your licensing model from an on-premise perpetual model to cloud-based subscription model, you can sign and approve that strategy. However, all of a sudden, your employees need to learn new skills to make your software suitable for the cloud. More importantly, they now need to provide 24/7 maintenance support to keep the system running. This will require people to change their behavior. Your sign-and-go strategy has now become a behavior change strategy.

Figure 2.1 Different buckets of strategic initiatives. Sign-and-go versus behavior change

Exercise: Divide and conquer (10 minutes)

Take a moment to look at your strategy and write down a list of all your strategic initiatives. Take a piece of paper and draw a line in the middle. Divide the list of initiatives of the two categories: sign-andgo and behavior change. Can you now select an initiative from the behavior change category that would make all the difference to your overall company strategy?

Difficulties With Behavior Changes

Often, management believes the reason teams struggle with strategy execution is obvious. As a manager once told me: “The team just lacks commitment and accountability.” Some say that their teams don’t have the right skills to make significant changes. Other reasons could be that people aren’t feeling trusted, there are misaligned compensation systems, poor development processes in place, poor decision making, or people are simply not held accountable for results.

Although all above reasons might be valid, we can assign them to one root cause. It’s the complete organizational system that is responsible for the inability to achieve strategic goals. To quote the authors of 4DX: “Any time the majority of people behave in a particular way the majority of the time, the people are not the problem. The problem is inherit in the system. As a leader you own responsibility of the system” (McChesney, et al. 2012, 5). More often than not, it appears that if people don’t understand the strategy or the goals, they are not committed to it.

Old habits die hard, as they say, and just because teams have received word from management that they need to change or do things differently, this does not at all mean everyone will be jumping on board. Behavior changes might require more drastic means, such as shuffling team members and reassignments to expose them to other ways of doing things. This is going to be uncomfortable for everyone involved.

The Number One Enemy of Behavior Change Strategies

In many cases, the greatest enemy of failing strategy execution and thus OKRs is your daily work. BAU, or also the “whirlwind,” pulls at us like a gravitational force. It distracts us every time and prevents us from achieving our goals.

BAU is all the stuff you do to sell, build, and make your customers and employees happy. To companies with software teams, I would like to mention that, yes, developing software features is BAU, too! What else would your development teams do? At the same time, it also prevents you from executing something new.

The whirlwind, BAU, old habits, status quo, and mediocrity are something that we humans love, no matter what we call it. Staying in our comfort zone, we go to work and do our “thing,” day in and day out. We are on autopilot, doing what we know has worked before. As a consequence, we learn a little less every day and achieving ambitious goals is not even on our radar. It’s the work and behaviors that people don’t like or don’t do yet that will boost their and the company performance.

Systems thinking theory (Meadows 2008) teaches that any time you try to change a stable system, you are likely to fail, because it always wants to go back to its status quo. It is the same with your organization and teams. Every initiative you launch that tries to change will be pulled back by the gravitational force of the system that we call BAU.

The Business as Usual Trap

Once you get started with OKRs, it is tempting to use them widely and indiscriminately. Every goal in your organization seems a potential candidate to transform into OKRs. Converting all of your BAU goals in your organization into OKRs is a natural response from many leaders who are new to OKRs. You can use OKRs wherever you use goals, but that doesn’t mean you need to. Initially, it will provide value: Your goals will become more measurable and structured. They are also transparent and give you frequent feedback, but it’s a trap. Before you know it, you are back to mediocrity, now managed by OKRs, and nothing significant has changed. Also, you end up with hundreds of OKRs throughout the organization, so it’s no wonder you need OKR software to “manage” them.

I’ve visited many organizations where the label “OKRs” is used everywhere and has lost its transformative power within the organization. People start to “OKR” everything, resulting in generic and soul-less OKRs. If, instead, you want to make significant changes, you must use the label “OKRs” with care. Only use them for executing behavior change strategies, your breakthrough goals.

The Breakthrough Goal

Habits are hard to beat. Probably the most important limitation that needs to be considered when changing behavior is that you simply cannot change too many behavioral traits at the same time. It’s for a reason that there are these 30-day challenges to get you back in shape, to quit smoking, and to change your diet. Changing human behavior takes focus, determination, and time, and you can only change a limited number of habits in a short period.

Therefore, breakthrough goals form a central component of the Lean OKR philosophy. If you don’t focus, and if you don’t make tough decisions, then OKRs won’t have the impact they could have in your organization. You need to learn to say no, even to great ideas that come your way, in order to create real focus and see real results. As attention and focus are often totally wrapped up in the sign-and-go and BAU activities, the place where focus would truly make a difference too often gets pushed to the backburner. The focus needs to be on one breakthrough goal represented by a single set of companywide OKRs.

Breakthrough goals go under different names, for example, step change, crowbar, or booster. As we can also learn from 4DX author McChesney: “Breakthrough goals almost always require a change in human behaviour. This is not something you can demand from your teams; rather, you will require the commitment of their hearts and minds” (McChesney 2020). You reach this through granting them trust and autonomy. In Chapter 5, you will learn how to select the right breakthrough goals.

Figure 2.2 Three buckets to divide your strategic aspects into. Breakthrough goals (Lean OKRs) are part of your behavior change strategy

The behaviors of your company’s people may prevent you from achieving growth and executing your strategy, and this may include your own past behaviors that have fed into the status quo. Any growth strategy that creates significant breakthroughs eventually requires a behavioral change strategy. This should be clearly distinct from sign-and-go strategies and the operational framework of BAU (see Figure 2.2).

How can you achieve your growth strategy in the midst of day-today operations? Hire more people? Maybe hire better people? Growing and improving your workforce is only part of that strategy. You also need to change people’s behavior to adapt them to new ways of working. You need an approach to align, engage, measure, motivate, and create accountability in teams that enables them to execute your growth strategy. I am talking about complete enterprise agility, responding to market change when it needs to. It is all about how your customers, employees, co-workers, and teammates behave. OKRs are meant for this. They are the tool you can use to achieve this behavior change in and outside your organization.

Example: Breakthrough Goal

Let’s say that you are leading a SaaS company and decided to conquer a new market, in this case the health care market. This decision can be categorized as a sign-and-go strategy. However, it could be that you now require a breakthrough goal to open up this new market. You created the following OKR for your company:

Objective: Crack the health care market.

KRs:

• Increase total health care customers with a basic subscription from 0 to 200 per week.

• Increase total health care customers with a premium subscription from 0 to 20 per week.

• Increase number of daily active health care customers from segment XYZ to 100 per day.

Now it’s time to challenge everybody in the company to move the needle on the KRs in the next 90 days. Because you are entering a new market, not only your new customers need to change their behavior to start using your product but also your employees need to change their behavior and habits in order to serve this new market. The Lean OKRs will compete with all your BAU goals to improve on your operational KPIs to make sure you stay in business. So to taking a chance against your BAU, you want to focus on only a single OKR and build in the OKR cycle to have a fair chance of winning.

Investing in Breakthrough OKRs

It has to be kept in mind that Lean OKRs are what teams must do in addition to their BAU activities, integrating into their daily working patterns. This doesn’t mean people need to work harder, but they need to work smarter. Some companies allocate 20 percent of their annual budget to work on OKRs, while others make allocation of resources the responsibility of the teams. The amount of time and energy that teams need to spend on OKRs will be different each quarter, because the nature of the OKRs might be different. One quarter the OKRs may be about generating more leads and the next quarter they may be about customer satisfaction. This means some teams will barely spend 20 percent of their time on OKRs, while others may spend maybe 70 percent of their time on their OKRs (see Figure 2.3). As you will read in Chapter 5, sometimes teams cannot contribute to company OKRs at all—which is fine.

In product development, it’s a different story. Since most OKRs will be focused on customers and products, most of your teams will spend more than 70 percent of their time on OKRs. That said, from my own experience I see that, especially in larger companies, in the first few cycles, the company OKRs tend to be focused on changing internal employee behavior. This internal focus allows leaders to make significant changes in internal processes, flow, and product quality. Even more importantly, they allow for experimentation within existing products as well as new markets. As a result of these improvements, the daily operation runs more smoothly and more time can be spent on (and experimenting with) change of customer behavior, which ultimately leads to growth and innovation.

Figure 2.3 The distribution of BAU and OKRs “work” can change per quarter and per team

In many cases, teams jump from OKRs straight into what are sometimes called “OKR initiatives.” They believe they can define a whole list of action items upfront, at the start of an OKR cycle, to achieve the Objective. If it is possible to achieve your OKRs that easily, by simply defining initiatives, projects, or a to-do list, then it is probably safe to say that your Objective wasn’t that much of a stretch to begin with.

The Horrible Action Item List

So, what are the specific reasons that an action item list approach is not recommended for achieving OKRs? Mike Rother, the author of Toyota Kata (Rother 2009, 30) provides a summary that explains it all:

• It is inefficient. Honestly, how many change initiatives or tasks have you been working on for the past months? Which of them have had significant results? It looks like a lot is happening, but in reality, there is little progress.

• We are in the dark. Running multiple action items at once doesn’t give us a clear picture of what works and what doesn’t. Admitting that you don’t know what to improve to achieve your OKRs is perfectly fine, but often so hard to say.

• We are asking ourselves the wrong question. “What can we do?” is the wrong question. “What do we need?” is a better and more difficult question.

• We are jumping to countermeasures too soon. A lot of the time we jump to conclusions even before we truly understand the situation.

• We are not developing our people’s capabilities. If it is easy and just part of their normal job, then people are not learning how to expand their problem-solving skills. If, however, you can equip your people with these skills, you will also reap the long-term benefits.

The more action items we have, the more “productive” we feel, but executing these action items doesn’t require anybody to change their routines or habits. To achieve significant results, we need to systematically change the behavior of people (customers and employees). A list may work when you are in fact converting your BAU goals into OKRs. However, this means you would simply be defining a focused form of BAU work.

If OKRs are employed in this way, people will continue to complain about a lack of focus and direction. Even worse, if you try to capture all of your “business as usual” activities using OKRs, then what is the point of using OKRs in the first place? OKRs are not a tool to replace operational management tools and techniques; therefore, it is easy to predict that if this is your approach, you probably won’t achieve any of your goals and, before you know it, OKRs will be the next management fad in your organization.

Project Portfolio Management

Larger companies often use project portfolio management (PPfM) to focus on doing the right projects at the right time, by selecting and managing projects as a portfolio of investments (Oltmann 2008). Managers can use company OKRs as a direction to help in selecting the right projects. This might seems like a good solution, and I’ve seen this approach many times in practice. However, projects actually aren’t very suitable for achieving OKRs. There are four main reasons for this:

1. OKRs require stable, cross-functional teams to run small experiments. Often, project-based teams are created only for the duration of the project. This will prevent people to continuously learn as a team. In Chapter 6, we will explore in more detail how teams best function in the context of OKRs.

2. If OKRs are truly stretched goals, you will not be able to plan and estimate projects upfront, because you will be running into unknown territory all the time. You can only start projects if the risks are limited and the work is predictable, that is when you know how to achieve a certain outcome with a fair amount of certainty. Often achieving OKRs is the opposite, they are about taking risks, making bets, learning, and experimenting. They are about achieving ambitious goals. In Chapter 12, you will find out more about how to run these experiments.

3. Sometimes people treat OKRs as a project in and of itself. For example, by having an Objective as “Finish project XYZ” or “Launch customer X on our platform.” Then, these projects often are separated into phases: for example, an inception, elaboration, construction, and transition phase. Then, within these phases, you can have milestones such as “requirements defined” or “testing completed.” However, these aren’t necessary good progress indicators to track progress on a weekly basis, neither will they result in behavior change.

4. Projects run over and fail with disturbing regularity. In an alarming study, 1,471 IT projects were compared on budgets and their estimated performance benefits with the actual costs and results. When they broke down the costs running over, they found something that “the average overrun was 27%—but that figure masks a far more alarming one. Graphing the projects’ budget overruns reveals a ‘fat tail’—a large number of gigantic overages. Fully one in six of the projects we studied was a black swan, with a cost overrun of 200%, on average, and a schedule overrun of almost 70%” (Flyvbjerg and Budzier 2011).

If you would like to learn more, I recommend reading the mini book #noprojects (Leybourn and Hastie 2018). In it, the authors argue for the use of adaptive portfolios, which consist of initiatives that continuously deliver (customer) value, rather than a sequence of activities with no clear outcomes. The launch of a new website, the implementation of a new office application, General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) compliancy, but also the implementation of OKRs themselves are examples of such initiatives. However, don’t fall into the trap of adding “OKR initiatives” to your portfolio, because all your initiatives inside your (enterprise) portfolio will fall into the categories we discussed earlier: sign-and-go or BAU. In Part 3 of this book, you will learn how you can best achieve OKRs without the need to run long initiatives or projects.

Traditionally, Return on Investment (ROI) was used to justify the budget of a (large) project. Now, by employing OKRs, people are able to better describe the ROI in terms of the business outcomes. Although this is partly a very positive development, the true nature of OKRs starts to fade when they are used like this.

This can be illustrated by an example from software product development, which is on the rise worldwide. Many people suppose that describing an initiative, a feature or project goal in the OKR format will help software engineering teams to think in outcomes of the project (“Increase the conversion rate from free to paid accounts of 2%”), rather than blindly taking orders (“launch new feature X”) from product managers or product owners—a phenomenon known as the “feature factory” (Cutler 2016). They are right that the latter could contribute to the conversion rate, but does this strategy help you to know if you are having actual success? Is the success of your features measured after they are released? By describing the outcome instead of taking orders (focus on output), you give the autonomy back to the team/engineers, so they can leverage their knowledge and skills to solve the problem. When you don’t reserve the label “OKRs” only for big transformative changes, their transformative power is watered down.

Key Considerations to Solidify Your Success

Now that you know for which kind of companies OKRs are most suitable, what purpose they serve, and in which kind of cases they should be applied, I will give you some practical advice on what you should further consider to make your use of OKRs a success.

Emotional Management

Introducing OKRs requires significant change in employee behavior and an even bigger change in your workplace culture. OKRs require people to change both their way of thinking and their way of working (which is their own invented, time-tested, most-efficient method for them, not necessarily for the business). What you are asking of people isn’t something small. Implementing OKRs isn’t a project that you do. It’s how you and everybody in the organization are going to work from now on.

To get people out of their comfort zone—which is what you do when you get them to change their behavior—you need to have a strong incentive. Without this, your OKR implementation will undoubtedly fail. The “why,” as described earlier, will give you some guidance. People need to feel the urgency. This requires senior management to increase the emotional temperature in order to kick-start this behavioral change; otherwise nothing will change at all.

Multidisciplinary and Multidiverse Teams

In my experience, the best, most innovative, and ground-breaking results stem from multidisciplinary and multidiverse teams. This goes beyond people with different professional skills and diversity in gender and nationality. The Inclusive Collaboration, founded by Dr. Sallyann Freudenberg and Katherine Kirk, is about learning how to harness the benefits of broad neurodiversity rather than attempting to wedge everyone into a constrictive monoculture (Freudenberg 2016). This means that a broad variation in people’s brains and how they function, for example, becoming manifest with regard to sociability, learning, attention, mood, and other mental functions, is approached as an asset. In my career, I’ve worked a lot with neurodiverse teams, and I have witnessed the most extraordinary solutions to really difficult to achieve (engineering) goals.

Ownership

Many executives make the mistake to hand over the OKR initiative to their HR department. Embedding OKRs into the DNA of your company should be the responsibility of one or more members of the executive team. Without their support, without their explanation of why it is important, implementing OKRs will fail. The reason is simple. OKRs are about executing strategy, and strategic planning is the task of the executive team. The executive team owns the strategic plan and also the highest level OKRs, the company OKRs. This does not prohibit you to involve other people to facilitate logistics and workshops when you cascade OKRs throughout the organization (see Chapter 5).

For OKRs to flourish, existing cultural and operational patterns of the organization need to be upgraded. If all existing patterns remain, then the organization will simply do more of the same (with the same subpar results). Even with OKRs in place, I have still come across organizations with siloed departments, misaligned teams, low employee engagement, even lower commitment, and little to no innovation.

If you have seen the attempted implementation of Scrum or DevOps to become more “agile” and they failed miserably, then why do you believe OKRs are promising? If change initiatives fail within your organization, then there might be a structural problem—a pattern. Evaluate the roadblocks and fix those first before starting to implement OKRs.

The most successful OKR implementations I’ve seen are within organizations that are already fluent in Agile practices (see also Larsen and Shore 2018). That doesn’t mean your organization won’t be successful in implementing OKRs, it just requires momentous upfront dedication from senior management, including intensive investment in:

• Team development and work process design

• Acceptance of lower productivity during (technical) skill development

• Social capital expended on moving business decisions and expertise into the team

• Time and effort in developing new approaches to managing the organization

How to Start Implementation

To increase the likelihood that OKRs will launch well within your organization, you should try to limit the scope of the implementation at first. It is important to devise a plan whereby you can test OKRs within an isolated environment with a trusted team before you communicate your vision and behavior change strategies to your workforce. This way you can evaluate some solid results from practical issues, adjust your vision and scope, have a sketched-out plan for introducing OKRs, and anticipate what the workforce could expect (how their world would change) and what kind of team(s) would be required. There are a few options but here are some of my favorites that I often recommend to clients.

C-Level Team

If you’re the leader of a company, on the board, or somehow in charge of the business, you might want to start with Lean OKRs with your executive team first. Since OKRs help you to execute corporate strategy, the ideal case is to start with all members of the executive team involved.

Perhaps, start by just setting a single OKR for a quarter to impact a critical metric within your organization. Don’t announce or distribute the full roster of OKRs just yet. Try using them within your C-level team for a few OKR cycles first. If they work for your team, you can present your learning experiences and insights to the rest of the organization. Furthermore, test driving first also means you’re talking from experience, not only theoretically. Leading by example is a management technique I favor and always recommend to my clients.

Pilot Project

Start a Lean OKR pilot project. Use a cross-functional team or department as your test group. When OKRs start to bear fruit, you can use this group as an example for other teams and departments. Alternatively, you can wait until other managers spot the team’s superior performance and use this as the trigger to experiment with OKRs at higher levels within your organization (hopefully now with those managers’ buy-in). It is important that you have buy-in from the executive team, since you will need their help to execute part of the strategy.

Educate and Scale OKRs

After you have booked some successes with the executive or pilot team, you can scale OKRs. Don’t rush into demanding all teams to set and use OKRs. Instead, use a phased approach, where you first provide education, background, preliminary results, respond pragmatically to questions or concerns and only then ask people to start using them.

In Chapter 5, we explore how cascading OKRs work in more detail, but here is a simplified version of an OKR rollout plan:

Phase one:

• Educate leadership team.

• Leadership team develops health metrics (KPIs) at company level.

• Setup a pilot product team

• Leadership team sets first company OKRs.

• Leadership team silently uses OKRs.

• Educate middle management.

Phase two:

• Educate teams, leads and form ambassadors.

• Middle management provides coaching to cross-functional teams.

• Teams develop health metrics (KPIs).

• Teams set OKRs.

Over to You

Exercise: Envision the ideal

How would the world within your organization look with OKRs, from beginning to end, and how would you get there? What kind of customer or employee behavior is aligned with that vision? What would you expect from your workforce? How would you define the success of OKRs?

Chapter Recap

In this chapter, we’ve explored the fact that using OKRs is challenging and addressed the five key reasons why many organizations fail. Throughout the chapter, I explained strategies to avoid such pitfalls.

We’ve established when and where to employ Lean OKRs, highlighting that this tool is commonly used to achieve big results—results that can’t easily be achieved at the normal rate of operation. We have addressed the importance of company culture, and the fact that a cultural, organizational, and behavioral shift is likely to be required for your company to implement OKRs successfully.

We’ve looked at how you might get started with Lean OKRs, by focusing on behavior change strategies, the breakthroughs that are required to make significant changes, how to keep things manageable, and how to foster companywide buy-in. The best application of OKRs is cases where a company or organization has reached a plateau and needs to essentially breathe a breath of fresh air into the way that they are doing things, both internally and externally, to reinvigorate teams, grow brand awareness, see their needle move, engage on a whole other level with their competitors, and achieve big, hairy, audacious goals that are thought to be impossible. They are ready to take risks, change behaviors, learn from mistakes, encourage regular communication through check-ins, and take front-end employee ideas to heart in improving the customer experience. OKRs are the cure for stagnation.

You should now realize that OKRs cannot magically solve problems with your company’s strategy. However, OKRs can help you execute that strategy when your goals are realistic and you enable everyone to engage in the process.

Chapter References

Birkinshaw, J. December 11, 2017. “What to Expect From Agile.” MITSloan. Winter 2018 Issue. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/what-to-expect-from-agile/

Cagan, M. December 11, 2011. “Measuring Innovation.” https://svpg.com/measuring-innovation/

Cagan, M. June 17, 2019. “Product is Hard.” Published by James Gadsby Peet Mind the Product Conference. www.mindtheproduct.com/product-is-hard-by-marty-cagan/ Video at: 08:07

Cagan, M., and C. Jones. 2020. Empowered: Ordinary People, Extraordinary Products. New Jersey, NJ: Wiley.

Cutler, J. November 17, 2016. “12 Signs You’re Working in a Feature Factory.” https://cutle.fish/blog/12-signs-youre-working-in-a-feature-factory

De la, Boutetière, H., A. Montagner, and A. Reich. 2018. “Unlocking Success in Digital Transformations.” Survey by McKinsey and Company. www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/unlocking-success-in-digital-transformations

Doerr, J. April 2018. “Why the Secret to Success is Setting the Right Goals.” Filmed at TED Conference, Vancouver, Video, www.ted.com/talks/john_doerr_why_the_secret_to_success_is_setting_the_right_goals/transcript?language=en

Drucker, P.F. 1977. People and Performance. New York, NY: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Duhigg, C. 2016. “What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team.” New York Times, February 25, 2016 www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/magazine/what-google-learned-from-its-quest-to-build-the-perfect-team.html?smid=pl-share

Flyvbjerg, B., and A. Budzier. September 2011. Why Your IT Project May Be Riskier Than You Think. Boston: Harvard Business Review. From the Magazine.

Freudenberg, S. 2016. “Inclusive Collaboration and the Silence Experiment.” InfoQ Article, www.infoq.com/articles/inclusive-collaboration-silence-experiment/ (accessed November 14, 2016).

Godin, S. November 13, 2018. This Is Marketing: You Can’t Be Seen Until You Learn to See. Portfolio; Illustrated ed.

Gothelf, J. 2018. “You Suck at OKRs. Here’s Why.” Medium, https://medium.com/@jboogie/you-suck-at-okrs-heres-why-84e7bf2836d3 (accessed February 9, 2018).

Green, P. October 6, 2018. “Who Is Neri Oxman?” New York Times, www.nytimes.com/2018/10/06/style/neri-oxman-mit.html

Groysberg, B., J. Lee, J. Price, and J. Cheng. January–February 2018. The Leader’s Guide to Corporate Culture, 44–52. Boston: Harvard Business Review Magazine.

Harris, M., and B. Tayler. September–October 2019. Don’t Let Metrics Undermine Your Business. Boston: Harvard Business Review.

Humble, J., J. Molesky, and B. O’Reilly. 2015. Lean Enterprise: How High Performance Organizations Innovate at Scale. 1st edition. Sebastopol: O’Reilly Media.

Kaplan, R.S., and D.P. Norton. October 2005. The Office of Strategy Management, 72–80. Boston: Harvard Business Review.

Klau, R. 2018. “How OKRs Fuel Innovation.” https://rework.withgoogle.com/blog/how-OKRs-fuel-innovation/ (accessed May 01, 2018).

Kohavi, R., and S. Thomke. September-October 2017. The Surprising Power of Online Experiments. Boston: Harvard Business Review. From the Magazine.

Larsen, D., and J. Shore. 2018. “The Agile Fluency Model: A Brief Guide to Success with Agile.” Blog: https://martinfowler.com/articles/agileFluency.html (accessed March 6, 2018).

Leybourn, E., and S. Hastie. 2018. #noprojects. C4Media, publisher of InfoQ.com

Litré, P., D. Michels, I. Hindshaw and P. Ghosh. 2018. Results Delivery®: Busting Three Common Myths of Change Management. Bain & Company. www.bain.com/insights/results-delivery-busting-3-common-change-management-myths/

McChesney, C. July 16, 2020. Executing in Complexity. YouTube. https://youtu.be/vOYj_-pYpPc

McChesney, C., S. Covey, and J. Huling. 2012. The 4 Disciplines of Execution: Achieving Your Wildly Important Goals, 1st ed. New York, NY: Free Press.

Meadows, D. 2008. Thinking in Systems: A Primer. London: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Oltmann, J. 2008. “Project Portfolio Management: How to do the Right Projects at the Right Time.” Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2008. North America, Denver, CO. Newtown Square, PA. Project Management Institute.

Osmak, I. 2017. “Why OKRs Fail.” Medium, https://medium.com/@iosmak/why-okrs-fail-fc9ad804dde9 (accessed June 9, 2017).

Sull, D., C. Sull, and Y. James. 2018. No One Knows Your Strategy—Not Even Your Top Leaders. Cambridge: MIT Sloan Management Review. February 12, 2018. Obtained from https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/no-one-knows-your-strategy-not-even-your-top-leaders/

Sull, D., R. Homkes, and C. Sull. March 2015. Why Strategy Execution Unravels—and What to Do About It, 58–66. Boston: Harvard Business Review.

Willis, J. October 23, 2012. “Neo Taylorism or DevOps Anti Patterns.” Portland: ITrevolution. https://itrevolution.com/neo-taylorism-or-devops-anti-patterns/