In the previous chapter I explained how culture is understood, generally and in an organisational context. This chapter summarises how, having understood how cultures are formed, we may use this to start to build a cohesive approach to embedding cybersecurity values into organisations, industry sectors and even, arguably, nation states, through a cybersecurity culture.

For many of this book’s readers their role will be to bring about a change in culture within an organisation or to ‘develop a security culture’. The scale of this journey is, as you will anticipate, large, so this chapter is not a definitive guide, nor is it a checklist to take to your CISO or board. It is, however, a small but influential part of the ABC journey to help enable you to take a confident step forward on this most critical of tasks.78

In the previous chapter we mentioned the mantra that culture comes from the top down. I explained an alternative, and complementary, view to this, where culture came from every direction. There are plenty of examples of cultural values at work where the leadership of an organisation is not present or, in some cases, is the target of employee displeasure about the cultural gap between what the employees understood to be the organisation’s values, and what the leadership are describing them to be. These, on their own, illustrate the need to see culture more broadly than just a ‘top down’ challenge.

The ‘top down approach’ is widely accepted by many commentators, especially those commentators from Western cultures or those familiar with Western management styles or theories. I think it’s only fair to say that some readers of this book, with different cultural values, may disagree entirely or partially with this assumption. And, as someone who has taken the time to research ‘culture’ without the ‘cybersecurity’ overhead, I’m entitled to agree.

Organisations and their leadership are, on the whole, reluctant investors in cybersecurity. In the ideal world there wouldn’t be a need to invest in security. However, the world isn’t ideal and it is, I’m happy to say, full of people.

As an observation, based on my own 20+ years’ experience working within the industry, the biggest drivers of investment and change appear to have been: suffering from an incident, statutory obligations, regulatory obligations and supply chain pressure.

When it comes to engaging a new supplier or going through the process of contract renewal, we’re seeing a small but growing trend for supplier organisations to provide assurance that they have in place an education and awareness strategy or plan. Some contracts seek assurances about security culture specifically. This is something your client-facing CISO and legal counsel are most likely to come across. In my experience most of these requests for assurances related to contracts or suppliers working in regulated industries such as finance and insurance. However, with legislators and regulators increasingly upping their game I forecast that we will see a rise in requests for such assurance. This will focus attention across organisations on answering this in a meaningful and demonstrable way, just as ISO/IEC 27001, NIST, GDPR and other trends within supplier management have done in the past.

CAN CULTURES BE CREATED?

The question of whether a culture can be created is really irrelevant. This is because the nature of humanity means that the mere existence of a group of people, that is two or more people living or working together, means that they will develop a set of acceptable norms, and values that underpin these, for how they behave and interact between themselves. This is culture.

A better or more helpful question is, ‘should I create a “security culture” or can I create a security culture within an existing culture, such as within an organisation?’

The phrase security culture could be interpreted as a culture separate and distinct from another culture. Is this actually helpful when engaging with stakeholders across the organisation? Is this what we actually mean when we use the phrase ‘security culture’? Or are we actually talking about embedding security into an organisation’s, or even across a society’s, day-to-day culture?

Again, the answer to the last question is likely to be, yes, we are talking about embedding security into an organisation’s culture: in fact a culture will already exist. Whether this culture was planned or has evolved organically and not on an agreed and desirable path is another question entirely. The organisation’s founders and leaders will instil their values and practices. Those values, behaviours and the culture that succeed and enable the organisation to survive and then grow will become recognised as the acceptable practices and norms. New employees will bring with them their own cultural attitudes and perceptions towards security from their previous experience.79

Bearing in mind the above, for many the question is not whether a culture can be created but rather whether the existing culture can be changed.

CAN CULTURE CHANGE?

Again, the answer is yes. If culture is formed through the processes outlined in this chapter then changes in those processes will naturally result in a change of culture. Culture is dynamic and is shaped by the forces at work in the environment within which any group of people live, work and play.

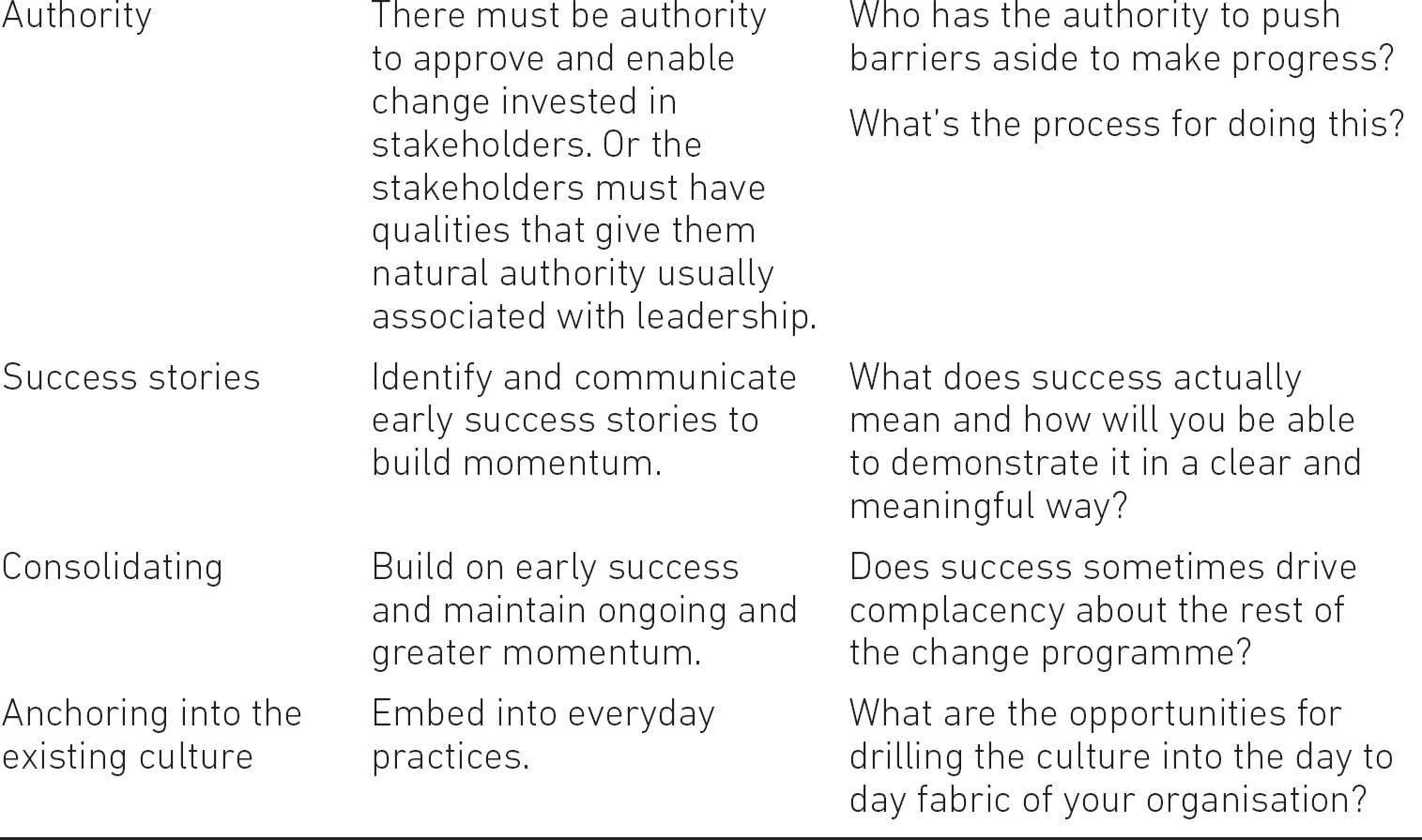

But change at a cultural level is a significant investment of resources. Change in any context requires organisations to go through the stages outlined in Table 7.1, according to Kotter.80

Table 7.1 Kotter’s stages for change

I would add to Kotter’s well-recognised process that the precursor to the stages in Table 7.1 is to understand how behaviours are formed and influenced. After all, effective change is about understanding the human factor and designing your change programme with that understanding in mind.

WHY CHANGE CULTURE?

Given that changing culture seems to be a difficult process, why would a CEO, a manager or even the security professional attempt to change it? There are many reasons but we can group them into three categories, discussed below.

External factors (compliance and precedence)

Governments and industry regulators are a key driver of change in terms of the time and effort organisational leaders pay to information security and risk management.

Governments prefer stability within which economies and societies tend to, historically, grow more effectively. This growth and stability historically has kept the majority of the population happy and the status quo has been maintained. This in turn means those in power retain this power, especially in cultures with a greater power distance ratio, between those at the bottom and those in power at the top.

Laws and regulations are much like organisational policies. They are tools governments use to intervene and drive perceived stability around agreed acceptable norms. They may not always be used effectively; however, they are part of the government’s arsenal to intervene to embed policy. In organisational culture these would be espoused values.

Increasingly we are seeing these tools stipulate the need for organisations to implement a security culture. Possibly of greatest impact, we often see through the media and legal review that regulators and the courts are pointing the finger of blame at CEOs and the board for creating or enabling an environment where negative cultural attitudes within an organisation towards cybersecurity or privacy were allowed to foster. And that this is the root cause behind yet another breach and not the failure to update a piece of software. This lack of an appropriate culture is then the backdrop for calculating the penalty or fine handed to the CEO and other stakeholders. And those fines are getting bigger. And the damage to the individuals’ reputation is getting larger and becoming difficult to move on from in some cases.

Thus, we see culture change initiatives being driven from the top down, as senior managers mandate changes in processes and routines to enhance compliance. Another reason for adopting this top down approach, at least for organisations with a general Western cultural emphasis, is that regulators increasingly point to ‘toxic culture’,81 a ‘lack of culture’ or something similar, from the top, as the reason or root cause behind some of the biggest data security breaches we see reported in the media.

We can see how governments and regulators are starting to view culture and its influence in organisations by looking at the UK FCA and its views. We’ve already come across some of its views on organisational culture in the previous chapter; now let’s examine its views on security culture. The FCA82 has stated:

We expect ‘a security culture’, driven from the top down – from the Board, to senior management, down to every employee. This is not as vague as it sounds – I will elaborate further.

We are looking for firms to have good governance around cybersecurity in their firms – by this I mean senior management engagement, responsibility – and effective challenge at the Board.

We are aware firms have found it difficult to identify the right people for these roles – but much progress has been made, and I am encouraged by the engagement we have seen on this issue by senior management.

While the FCA’s guidance here is helpful, it does highlight shortcomings in terms of defining how to comply with any requirement for an appropriate ‘security culture’; governance, or espoused values as cultural specialists would call it, is not all that makes up ‘culture’, as we have discussed previously. The FCA’s interpretation of what culture means, or how it can be evidenced, in itself shows a limited understanding of how cultures are formed and influenced. This may play well into the hands of those who see culture as a tick-box exercise rather than a means to drive changes in risk stemming from employee or other stakeholder behaviour.

As a further indication of how regulators view culture, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS, 2020) has published its Information Paper on Culture and Conduct Practices of Financial Institutions, in which it states:

Culture is generally understood as the shared values, attitudes, behaviour and norms in an organisation. It is driven by both the ‘hardware’ (e.g. policies and processes) and ‘software’ (e.g. beliefs and values) in an organisation.

MAS also places a requirement on senior management to ‘walk the talk’ and appoint culture and conduct champions. The top down approach must be met by an ‘echo from the bottom’ with rewards for employees seen to be embodying the culture in their work. Finally, the paper states that:

The various components contributing to the culture and conduct of an organisation do not work in isolation. They are inter-related and can help to complement and reinforce each other.

– a point that we heartily echo.

I would also re-emphasise here the increasingly clear message, from regulators in their industry engagement and education roles, for organisations to demonstrate an appropriate organisational culture when it comes to cybersecurity and what this might mean. Regulators need to understand that the words they use can either create a rod for the back of security professionals and drive a compliance culture or, if done properly, can equip stakeholders responsible for delivering cultural change with meaningful leverage via legislation, precedent and education.

Here I raise a word of warning. The CISOs, and education and awareness managers I work with understand the value of drawing on regulator commentary and findings from investigations. This helps them set out clear objectives when it comes to culture strategy. However, time is against you if your strategy is based on what others say instead of developing your own vision. Let me explain.

When a regulator, judge or even customer, comments on their understanding of the term ‘culture’, it must be remembered that it was at a single point in time. Regulators’, judges’ and customers’ interpretation of the term ‘culture’ is likely to change. This change is a result of them becoming more aware, educated and knowledgeable on how cultures are formed and influenced. Sometimes this will be as a result of their own research and sometimes as a result of what the collective understanding is, among the groups and cultural institutions within which they live out their lives. Why is this important?

If you use only these terms and definitions, comments and precedents as the guiding principles behind a new culture strategy, and let us say, for argument’s sake, that the desired culture change takes three to five years to implement, then it is quite likely that the regulators’ interpretation of culture will have changed. Basically, if your strategy for cultural change is based around delivering against what regulators say now, then you are setting yourself up to fail in three years’ time.

An effective strategy for change is about delivering where you need to be in the future, not where you should be now!

We should recognise that there are many other external factors apart from compliance and precedence, such as the competitive environment, sales performance, competitor and consumer behaviour, and national and sub-culture values that can influence our culture, our values and our behaviours.

Internal factors

A new CEO; a change of strategy; a ‘burning platform’; an incident. There are many internal factors driving change across an organisation. Many individuals speak of culture being (part of) an organisation’s DNA83 and hence slow to change; however, there may be components of that culture that are valid and have a decisive role to play in the organisation’s future.

Typically, most cultures change over time to a greater or lesser extent, as the environments in which those organisations work change and the people inside the organisation change as well. We’re not going to look at these gradual changes – which may be almost imperceptible – but we should acknowledge and remember that any culture is dynamic.

Instead, we’re going to look at planned or reactive cultural change; that moment when someone (or a group of individuals) inside the organisation recognises that part or all of the culture is a problem. A classic example of this is the IBM culture change overseen by Louis Gerstner,84 where an outsider, brought in at senior level, understood that culture was the problem and needed to change with the help of IBM’s employees themselves.

From a security perspective, an incident can be a real signal to senior management that things aren’t working; and a learning experience that technology is not the silver bullet they have been sold or led to believe. If the impact has been significant (in terms of business operations, media coverage, or customer feedback) then a well-led organisation will want to understand why and the causes behind the incident. It is at this point that behaviours and values – and questions such as: What did people do? Why did they do something? Why didn’t they tell us? Why didn’t they do certain things? – can be examined and cultural lessons learned. These can form the basis for the cultural change programme.

I’m regularly engaged by organisations ‘post-incident’ to help them rethink the human factor. If the board or senior management can resist the impulse to fire someone (typically the CISO) because the breach has happened, then the period after the incident can be very valuable in changing culture.

Organisational culture as a barrier or enabler

The role of culture in delivering more efficient organisational management is a relatively recent consideration from the 1970s.85 it is recognised that strong cultures can be a barrier to change86 and significant effort may be needed to make any change stick, including visible changes in leadership, reorganisation of business functions and long-term programmes. A weak culture can be changed but the reverse issue then appears, which is how to embed the changes and then make them stick.87

Organisational culture, as something made by human beings, will always have its ‘good’ and ‘bad’ characteristics. Note I use quotation marks, as ‘good’ and ‘bad’ are determined by personal perspective and the values the observer brings along with them (some may call these ‘biases’). Turning these characteristics into levers for change can determine the success or failure of a culture change programme; spotting which of these characteristics can be used to accelerate or reinforce change can also determine whether the culture will be a barrier or enabler.

Within the context of cybersecurity, the question of culture and its role in driving down risk has been talked about for some time, but its relevance has changed. Statutory, regulatory and contractual obligations increasingly specify the need to achieve a security culture. Regulators have clarified that they want to see evidence of the existence of a security culture and the courts routinely point to a lack of, or weak, organisational culture towards cybersecurity, when reviewing data breaches.

CHANGING CULTURE

No matter why we wish to change the culture, it must be run as a programme or project, with people, time and money assigned and objectives set. Importantly, one of the organisation’s senior managers, if not the CEO, should be the champion and sponsor of the culture change.

But we must explicitly recognise that culture change will happen at many levels of the organisation – from the board to the newest entry-level employee. So our overall strategy must address change at all the levels – not necessarily at the same time though – to make the changes we are seeking. For our change strategy to have impact, it’s often best to start at the top, with the board.

A word of warning – culture change is not taking a group of people away to a nice hotel for a couple of days and coming back with new slogans, titles and buzzwords. These sessions do have their place, especially if a set of values or norms can be created as the basis for a cultural change programme.

We’ll deliberately focus on culture change linked to cybersecurity and we’ll examine the key components.

Collaborate

I can’t stress this enough. Any culture change programme will be the result of a collaborative effort between many individuals, bringing their knowledge, expertise and enthusiasm to the work. You won’t be able to do this on your own and such an approach may well doom your efforts to failure. Know your weaknesses and bring in people who can provide the knowledge and expertise to complement your strengths and actively address your weaknesses. As you build your collaborative team to deliver change, make sure you and your team are demonstrating the examples and behaviours you want to be adopted and demonstrated in the organisation.

Create a vision

We hear much talk about vision and strategy for organisations and what those words mean. In our cultural terms, our vision is what we want people to do: the behaviours we would like them to display and the values we would like them to adopt. One stream of thought is to set out challenging and unique values;88 another is to find those cultural characteristics that are already there and build upon them by reinforcement.

The vision will form part of your toolset to help change the culture. It will be used as the basis of your formal communications and it will set the direction of your change. So, the advice is to keep it simple and memorable.89

Involve the board

So how does the board demonstrate the importance of security to its employees, supply chain, customers and other stakeholders?

You can start by looking at what the board and the structure that supports it pay attention to. What is it that they control and measure? And how often do they do this?

By ‘paying attention to’ I mean a number of things. What forces are driving the board to focus? What topics are discussed and what is the priority given to each? What decisions are they making as to where to bring about change? And then there’s the matter of what resources to invest in bringing about that change, and then maintaining and reviewing the security posture within the organisation.

It may seem obvious, but if the board never discuss security, never ask for information about security and only ever talk to the CISO when there is an incident, then other managers will take their cue from the board and ignore security. After all, if the board aren’t interested, then why should other managers be interested? Worse still, if the CISO is seen as the ‘person you fire after a cyber incident’, then other managers will keep their distance, as they don’t want to be linked to the CISO by association. You can see the insidious effects of an organisational culture running through this paragraph.

The reverse is also true; if the board take an active interest in any topic, discuss it regularly, then quiz managers about it and require regular reporting, people across the organisation will quickly grasp that the topic is important and actively change to meet the board’s requirements and match the board’s behaviours.90

By ‘control’, I mean what is it that they have clearly defined as being their expectations when it comes to security? How have they set out their vision, assessed their current position against this and then formulated, implemented and maintained a plan to bridge any gaps? What assessment of the current state of affairs is taking place and what reporting is in place to the board so that they are fully aware of whether their expectations are or are not being met? This is control. Making statements about cybersecurity, including value statements about the importance of cybersecurity, without backing, is little more than window dressing.

Obtain investment

Investment in security is a possible means of evidencing the embedding of cybersecurity into an organisation’s culture or, as a minimum, it is evidence of how the board can clearly demonstrate how seriously it takes the matter.

When thinking about investment within the context of cybersecurity, don’t limit your vision or interpretation of this to how much in terms of £s, s or $s is being spent or you would like to be spent, the technology you can acquire or the increase in your security budget. We are talking about different aspects of investment:91 the slow and careful commitment of resources using well-understood tools and techniques to achieve a defined aim; the personal act of spending your time and your efforts to achieve change.

It’s worth examining what is driving the decision to consider investment and, importantly, the process for making that decision, as well as the actual capital or operational spend. In terms of decision drivers, the key will be to understand the drivers for the board and senior management, both as a group and individually. These drivers will be many, varied and even contradictory; they may have external and internal influences; and they may be personal. Each board member or senior manager will have their own decision process, their own biases and heuristics and their own judgement on the value of making the investment. All of these will come together to create a decision backed by the board.92

Try to keep an open mind and remember that it is quite likely that different boards, especially in different cultures, will interpret the word ‘investment’ slightly differently, but probably with some common denominators.

In terms of drivers for investment, what is driving the board to look at the issue of security culture? Is it an actual security incident their organisation has experienced? Is it to address a strategic barrier to entering or operating in a particular market? Is it in response to a level of self-awareness about corporate responsibility to customers and more broadly society? Or is this about corporate resilience in a digitally reliant world? Or has the regulator told them?

Each one of these questions and answers says something about the priorities and arguably the values the board associates with security. Mishandled, they can act as a lightning strike that drives a wedge between what is said and what is actually done. This is the cultural dissonance I spoke about in the previous chapter. Handled well they can act as a rallying point giving certainty and assurance about what is socially acceptable within the organisation and the group of colleagues you interact with to ‘get things done’.

What does it say about leadership, where the board make a decision to invest having thoroughly assessed the business case, based on an understanding of the risk to the organisation’s key strategic key performance indicators (KPIs), compared to a board who conduct a benchmarking exercise against other organisations with a similar profile in the same industry? It is not unusual for organisational boards to ask advisory and consultancy practices to share insights into what other similar organisations are doing and investing.

Another comparison would be investment based on the need to comply with regulatory and statutory obligations where the minimum is done to get the organisation compliant and possibly certified. But when you set out with the objective of doing the minimum possible to get your organisation over the line of compliance, what does that say to those most closely involved in the programme, and those who you seek to influence across the organisation? Does it sound like security is really important and that it is truly valued by the board and the wider organisation? Probably, no.

Respond in times of crisis

Another telling sign of whether the security values are embedded within the organisation’s culture is how the board and senior management respond in a crisis or incident. As many security professionals can relate, many people in organisations from the top to the bottom just do not believe a ‘cyberattack will happen to us’, with many reasons given from ‘we’re too small’ to ‘we have nothing of value’ to ‘we’re better than the organisation that got hit’.

Much of this thinking can be attributed to biases and heuristics and their role in forming and influencing behaviours. We have a number of biases93 that apply when we think. In terms of cybersecurity, two biases can affect our thinking and our approach to incidents. The first is the salience (or saliency) bias, which describes our tendency to focus on items or information that are more noteworthy while ignoring those that do not grab our attention.94 A great example is that as cybersecurity professionals we focus on incidents as they are of personal interest to us, whereas clothing fashion professionals will probably focus on what they are wearing rather than incidents for the same reason. Another bias is the normalcy bias,95 which is the refusal to plan for or react to a disaster that has never happened before; in our case a cyber incident. And finally, there is the availability heuristic (see Tversky and Kahneman, 1973), in which we recall something similar to the event we are either discussing or being told about. Unfortunately, for many non-security people, the likelihood of a security incident seems distant. Presenting data that illustrates the frequency with which these incidents occur is a step forward to influencing people; but we also fight against these biases until something happens to them (or their peer group).

If the leadership team appear to not be in control in the wake of an incident, then many will question the seriousness placed on the matter of security in the first place. This is because several assumptions will be made.

- The organisation wasn’t aware – in which case why not? After all, ignorance is no defence.

- The organisation was aware but was in denial – this may be considered negligence.

- The organisation was aware and had a plan but it failed – this may be considered bad luck.

- The organisation was aware and had a plan that worked – great leadership and foresight (or just plain lucky).

When an organisation has a crisis, even if they have incident management plans, crisis management plans and so on, they will have to face two interrelated issues. First, the plan probably won’t cover the actual incident;96 second, no matter the roles assigned, there will always be someone (probably senior) who wants to take over and ‘be in charge’, regardless of whether that is the right action in the circumstances. The first can be solved easily through regular exercises using the plan, so that all participants view it as a framework to help them manage the incident. The second is less easy to solve, as senior managers tend not to participate in exercises and (by their very nature) want to be in control and leading the team.

We’ve also touched on the ‘CISO as fall guy’ approach, which basically results in the CISO being fired if an incident happens, regardless of whether the CISO or the organisation were capable of detecting and responding to the incident. This is a powerful indication of the culture and of the values of the organisation.

We can examine two changes to our culture. The first is to overcome the biases we have been talking about and to acknowledge that an incident could happen and to have a plan to handle it when it does.

The second is to build a culture where reporting suspected incidents (including data breaches) is seen as the ‘right thing’. We mentioned the significant number of data breaches being reported in the European Union since the introduction of GDPR in an earlier chapter. But is this increase because (suddenly) individuals and organisations have become worse at handling personal data? Has there been a sudden spike in incidents? Or has there always been this level of incidents but organisations and their employees didn’t feel either a moral or a legal obligation to report these before? Did they even reach out to the data subjects affected or make an effort to understand the likely risk to them of a failure in their own systems of control? The values that drive decisions like these, whether to report and communicate incidents, for example, are the values that lay the foundation for the role of cybersecurity within an organisation’s culture. We can and should seek to build a culture where reporting is valued and individuals are rewarded for noticing odd or strange activities and behaviours.

Culturally, responding to crises becomes not about pointing the finger of blame; it’s about acknowledging shortcomings in the processes in place and guaranteeing you’ll address those.

Challenge assumptions

In my early days within the security industry, before the phrase ‘cybersecurity’ was used, I routinely asked clients to look at their contracts with both suppliers and customers. Almost always the contract would have a condition requiring a third party to make assurances about confidentiality or a condition where the client made a statement assuring a customer about confidentiality. I’d then ask them on what grounds they could make such a promise or put their name on a contract that made it contractually binding. Back then the response was consistently the same, irrespective of who I was talking to. Whether at a board or, back then, the IT level, commonly there was no answer or an assumption that it was sorted, although by whom and how was not known. At worst, they didn’t really care. At best I was given a list of tactical interventions, from IT controls to HR and legal.

Where an organisation’s leadership’s sense of control is based on broad assumptions, this illustrates potential vulnerabilities in their overall control of the issues at hand. Where a board see the issue as someone else’s responsibility, like the security, IT, risk and compliance functions, this reinforces a sense that incidents that arise aren’t the organisation’s responsibility, but down to IT, cybersecurity, risk and compliance. Traditionally these functions only make up a small part of the overall workforce.

This approach ‘that someone else is taking care of it’ raises some interesting cultural insights. Among the insights are that: the organisation is very rigid – people do exactly what they are told and exactly what their job description says; ‘stepping out of line’ or ‘asking questions’ may be disliked or actively discouraged; and silo behaviour and silo thinking predominate. For topics such as information security that require cross-functional thinking and behaviours, this culture can be a real challenge to building all three of the ABCs.

Allocate resources

Is there a dedicated resource focused on improving or supporting the improvement of the organisation’s overall security posture?

I often find myself challenging clients about what they actually mean when they use the term ‘dedicated’. It may seem self-explanatory but, in my experience, people use or interpret common terms like this inconsistently. I’ve experienced ‘dedicated’ resources who have been dedicated to the responsibility but carry this alongside several other responsibilities. I’ve experienced ‘dedicated’ resources who have been given the responsibility but are not measured against the delivery of this or who have not been given the resources or support to implement what they want to get done.

To be clear, culture change takes time and requires resource and expertise. When we talk about dedicated resource, we are talking about ring-fenced budget items and, more importantly, people who can spend the majority of their time (say 75 per cent plus) on the culture change programme. Not only that, the programme has milestones and measures to assess progress and success.

Does security have a budget or is it a matter of resources being made available on an as and when basis? The existence of a budget may be interpreted as illustrating the importance of security to the organisation. After all, the investment is a decision to invest in the future; it is a commitment, instead of investment based on responding to business needs that arrive on an ad hoc basis, which has a feel of ‘let’s see if we can get away with it’ about it. But money is only part of the story.97 Unfortunately, by creating a line item, or setting out a budget for security, it is then easy for people to say, ‘Look! We invest in security!’ However, as is well known, much of the security budget goes on tools and the people running them98 and there isn’t much room for the non-technical side of information security. In part, this spending on tools is to show a tangible return (you gave us ‘X’, we bought ‘Y’) but, I think, reflects the typical technology-led approach we see in cybersecurity. It is easier to buy a tool than to explain, justify and then purchase a ‘soft’ culture change programme.

Another common assumption, and therefore mistake regarding resource allocation, is that other stakeholders across the organisation will respond positively and facilitate everything the security function needs to bring about a change in organisational culture. Going back to the discussion earlier about what people perceive to be important and how that is driven from the top, and our discussions about the fact that cybersecurity just doesn’t register for many people, you have to tackle the ‘Why should I bother?’ If you can’t make the case that helping you will help those stakeholders, your work will be met with polite indifference or outright hostility.

Role modelling by the board

How does the board and senior management team provide deliberate role modelling themselves and throughout the organisational structure? In other words, do the board and the senior management team ‘live’ security, or ideally values closely associated with security attributes, in a very visible way through everything they do?

Getting visibly involved in cybersecurity initiatives as a figurehead seems to be the level of ambition of many. It’s something I always like to see done. Unfortunately, not all organisations have one or more senior individuals willing to become the figurehead for cybersecurity. Without such a visible individual, it becomes harder to make the case for cybersecurity, as we have discussed earlier.

A figurehead on their own doesn’t make much difference. You should plan on how to use your figurehead across the ABCs and as a key role model in your culture change programme. In some ways, I would suggest that you sort out your programme and then appoint a figurehead; hopefully they will be enthused by the programme and act as both a supporter and an advocate as part of their role. It may be better for your potential figurehead to understand what they are signing up to in terms of your programme before they front it, rather than signing the individual up first and then developing your programme. Be careful, as well, of having a figurehead and then not supporting them. If people are willing to help, remember to reciprocate and provide them with information, take time to talk to them and equip them with the information they feel they need to be credible and useful. If you don’t, you will lose your figurehead and you will also see a degree of cynicism and a lack of appetite to help you in the future. This is a two-way relationship.

Role modelling is both a conscious and unconscious activity. People in all walks of life at all stages act as role models, sometimes unknowingly. And unconsciously or consciously, people are drawn to and influenced by these.

As a young teenager who loved sports, and played for the school, I distinctly remember admiring those who played in the more senior rugby and athletics teams. I remember the inspiration I got when a sixth former handed me a pair of running spikes for my 100 metres race and explained why they’d be of help. Or the full back for the school’s first XV rugby team who sat down and talked me through how he played the role and invited me to watch when the team played a home game.

As I mentioned in the previous chapter, our choices, and the behavioural outcomes from these, are heavily influenced by what we see others doing around us. We are naturally, and subconsciously, tuned to mimic the behaviours we encounter day to day, especially those that belong to a person we might aspire to be, or that appear to result in recognition, success or both.

Setting an example through role modelling is one way of leveraging this subconscious-primed response within the human. Leaders may acknowledge that this is the case, but do they consciously fulfil their ‘role model’ roles? Or is their approach ‘do as I say, not as I do’? For example, do they follow the organisational policies, processes and procedures where it suits them but bend these when the situation doesn’t suit their needs and purposes, and do others around them experience this? If they don’t follow the rules, can they be held to account and will they be?

We should also acknowledge the fact that not all role models are exemplars of following the rules, good behaviour and cultural norms.99 In fact, these individuals are sometimes required to break previous cultural norms to help reset or change the organisational culture.

Build rewards and recognition

How does the leadership team and operational management recognise appropriate behaviours and reward these? This includes enhancing the status of individuals who have demonstrated behaviours that are in line with cultural values.

The MAS report quoted above also suggests that ‘Staff [are] recognised for exemplifying financial institution’s values’,100 and this taps into a wider discussion about how we can reward individuals who display the ABCs in a positive matter. Over the years we’ve all heard and participated in discussions about tying people’s pay rises and bonuses (or components thereof) to cybersecurity achievements or milestones. An example of this approach can be seen in the context of health and safety where a bonus is awarded if a stated number of accident-free days is exceeded on a site, coupled with evidence of regular training and awareness. Interestingly, I’ve never heard a discussion where the same model should be applied to cybersecurity professionals.101

Of course, the issue here is multifaceted. Let’s just focus on five components: measurement, legal, human resources (HR) and culture:

- Do we have the capability to measure everyone’s behaviour and specifically security-related behaviour all of the time they are at work, irrespective of location?

- Legally, can we monitor, track, record and then openly publish people’s behaviour?102

- Can we have the same set of rules, rewards and punishments globally?

- How comfortable are we as cybersecurity professionals and the organisation in pinpointing and calling out individuals for security errors or breaches and then tying that to promotions, monetary rewards and bad publicity for breaching the security norms?

- Does the organisation really care about cybersecurity that much to do all this and change the reward structure?

It’s the answer to the last question that often means this idea is a non-starter. Simply, the answer is no.

So instead if thinking in terms of punishment, let’s turn to reward. We’ve mentioned that positive reinforcement is a much more powerful tool, and there are many examples of cybersecurity staff leaving balloons, chocolates and other rewards on people’s desks where they have demonstrated a security behaviour (such as locking a laptop or having a clean desk). As part of our cultural change, these are important symbols, rewards that can serve as the basis for stories and myths. However, we need more than just chocolates. When we think about rewards and recognition, we are likely to focus on the behavioural aspects and outcomes, as these are readily visible and easy to communicate. But don’t forget that culture is more than just behaviours.

If we wish to develop or change rewards and recognition, then we’ll need to work with the board, human resources (or equivalent) and the internal communications functions. Obviously, when we think about rewards, especially those that involve money or personnel records, we need to engage stakeholders to understand how reward systems work and how we can work with HR to record good behaviours, reward them through the appraisal and review systems, or reward them through other approaches (such as spot cash rewards) and so on. If employee recognition systems are used, then we need to understand how recognition is performed, the systems used to capture recommendations and then communicate the recognition to the employee and the wider organisation. We also need to work with the internal communications team to understand the style and frequency of reward and recognition communications.

Finally, we need to decide what we are going to reward. Behaviours are a good choice, as we can describe a situation, describe what happened and then discuss the behaviours shown and why those behaviours are worthy of reward. It is more difficult to reward the intangible aspects of culture as it can be more difficult to identify and describe them and draw out clear messages.

Recruit and retain

How does the recruitment process reflect the importance of the cultural values associated with security? What role does an individual’s values, skills and attributes associated with security play in their selection for promotion or for getting their first job at the organisation?

It is a truism that many organisations – for example, financial institutions, technology companies and consultancies – recruit a ‘certain type of person’. The people they recruit often possess and demonstrate some or many of the behaviours and values the organisations want and which are already part of the culture. You can also correctly argue that individuals with certain cultural backgrounds and values will want to apply to these same institutions. This recruitment bias can lead to ‘monocultures’103 where cultural fit and shared values become ingrained and unchallenged.

It is a further truism that beyond cybersecurity job adverts, very few adverts call for cybersecurity values, skills, experience or cultural aspects. Interviews are typically used to explore cultural fit between the candidate and the organisation but – again – if security isn’t part of the culture, then it won’t be explored in the interview.

An aside and one that I feel is representative of our cybersecurity culture is the language and values we often use and describe in job adverts for cybersecurity roles. The words tend to be technical, masculine and individualistic; there can be the use of words linked to conflict and war. We should also look at ourselves and ask if we are expressing the right culture and values in our words and adverts; and if we really are attracting the candidates we say we want to attract. The words we use in our adverts may be unattractive to 50 per cent of the candidate pool. If that 50 per cent doesn’t apply, then we have already cut ourselves off from a lot of good people.

Stories, myths and legends

In the previous chapter I explained the role of both formal and informal education processes and institutions. In addition to these education processes, we also learn through storytelling. Every culture contains stories, myths and legends, and the power of storytelling is something that many within the security industry will have heard as a means to effectively raise awareness and influence behaviour towards an appropriate culture.

Humans seem to be hardwired in the brain to respond positively to storytelling. Well, good storytelling at least. Good storytelling bridges the gap between a simple narrative and an emotional connection that makes it all come to life. Context, or the plot of a story, turbo-charges words to draw us in, engage us successfully and improve the odds of something being remembered, retold and acted upon.104

Some myths and legends are introduced and fostered deliberately, and some seem to grow on their own, among personnel over time. Some are true, others are half-truths and some are fabrications. What some people remember, and subconsciously use to define what is or is not acceptable, may not even have happened to them. It might be something they heard that has become anchored in their subconscious as a truth by the organisation or state, as part of fostering the values and ideals that it aspires to or believes it embodies. It’s not dissimilar to developing a brand and then the process of making this come alive within an organisation. These values tend to be passed from person to person, even through generations, and to be done in an almost organic, informal way.

Formal statements

In the previous chapter I mentioned artefacts and espoused values. These are formal statements of the organisation’s philosophy when it comes to cybersecurity. They cover values or attributes such as confidentiality, integrity and availability, associated with information, systems and processes; they may also state the behaviours we wish people to adopt and demonstrate.

These come in the shape of policies, processes and procedures. You’ll find them communicated through formal internal communication campaigns or permanently added to the environment within which we work. It’s worth stepping back and considering the general level of knowledge about policies, processes and procedures, and then to consider the level of knowledge about the IT and cybersecurity policies, processes and procedures. In my experience, the two most read policies in most organisations are the holiday policy (‘How much time can I get off work?’) and the expense policy (‘What can I claim and how much can I get back?’); most people in an organisation wouldn’t even know there are IT and cybersecurity policies published and would have no idea where to find them or who to ask, even if they wanted to read them. And, let’s be honest, most IT and cybersecurity policies are not great reads.105

So, the reach of our formal statements as expressed in organisational policies is limited. There are other formal communications we can use, such as corporate newsletters, training, emails and so on but all of these have their limitations.

The best mechanism for driving cultural change is to take these formal statements and live and demonstrate them. This neatly ties back into our discussion of role modelling: making the culture a tangible thing so that people can see it, understand it and shape their behaviours to match.

We can also take key messages and turn them into slogans as part of a communication campaign. This is of course where we need to work with communications specialists, alongside our other specialists, to develop the simple and effective messaging that accompanies the changes we wish to make.

Job titles and responsibilities

It is widely accepted that there is a general skills and experience shortage in the security industry. However, this is amplified when it comes to finding candidates for job roles where raising awareness, influencing behaviour and fostering an appropriate organisational culture are the key objectives.

The shortage is highlighted as a result of an increase in demand from CISOs and the organisations they represent. This demand is driven by a number of factors. First, there has been an increase in statutory, regulatory and even contractual obligations regarding security education and awareness. The European Union’s GDPR as well as industry standards, such as ISO/IEC 27001,106 NIST Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity107 and PCI DSS v3.2.1,108 all place a requirement for organisations to implement demonstrable education and awareness activities.

Second, as we have mentioned previously, many contracts between organisations now include clauses demanding that suppliers can demonstrate the existence of an education and awareness programme designed to reduce risky data security and privacy behaviour. Having a job role bearing the title education and awareness or security culture manager is one way to tick the box.

Third, regulators’, the law court’s and even media’s interpretation of the role of culture and its link with security and privacy breaches is routinely made clear. Cultural attitudes, starting from the board down, are often highlighted as the root cause of many of the breaches investigated. The lack of an appropriate culture is often part of the reasoning behind penalties administered by the courts and regulators. It’s also a key element within media reporting post-incident.

With this in mind, organisations need to be seen to take this seriously. Rightly or wrongly, taking this seriously starts, for many, by creating a specific role with responsibility for this. Then there’s the matter of finding an appropriate person to fill the role. This is driving the increase in job vacancies and roles where security awareness, behaviour and culture are part of the job title or specification.

To be effective, as we have discussed earlier, the role must be assigned resources and the time for the programme to deliver. Merely giving someone the title will not improve any of the ABCs.

SUMMARY

Creating or changing a culture is a human-oriented endeavour. Just as culture is formed by people interacting, it is changed by the same thing. We’ve explored a lot in this chapter, from models of organisational change to collaboration and job titles in the context of changing culture.

Changing culture requires effort, the use of many tools, differing knowledge sets and the ability to understand both the tangible and the intangible; behaviours, values and their interactions; and the understanding of how to use a range of tools to express what has to change and to provide the impetus to change.

There is no one best way to change your organisational culture, nor is there one good reason why you should do so. If you embark on the culture change journey, there are many factors to consider and we would urge you to use this chapter as your guidebook to help you map out that journey and to help orient you as you travel onwards.

NEXT STEPS

It’s often said that practice makes perfect, so we suggest some actions you can take below:

- Identify a behaviour or value you would like to change.

- Describe what your ideal changed behaviour or value would look like.

- Draw up a roadmap of how you would like to change the behaviour or value.

- Identify who can help and when you need help.

- Define your measurements to show the change has stuck.