5

Reinventing the Promise of Work-linked Training… Or an Initiatory Journey Towards Agile Professionalism and Postural Learning

5.1. A study of the efficiency of French post-baccalaureate business schools

5.1.1. Introduction

The higher education system is one of the pillars of a country’s socioeconomic system, because it contributes to the dynamics of knowledge acquisition, capitalization and mobilization, as well as to the development of sustainable comparative advantages, and ultimately strengthens national competitiveness.

Nowadays, institutional pressures in the higher education ecosystem are becoming increasingly strong: they relate to market forces (starting with the accentuation of competition among institutions with organizational impacts, a weakening of the academic fabric, bankruptcies, as well as alliances, mergers and acquisitions, etc.), as well as political decisions, dictated by a neoliberal culture, making one of its hallmarks the withdrawal of the welfare state from the education sector (and its consequence, which is partial privatization).

However1, assessing the efficiency of higher education institutions – private and public – is a priority for both governments and the institutions themselves. This is because it is at the junction of new institutional injunctions, pushing for standardization and accreditation on a global scale – the market being appreciated here as a founding institution of what the socioeconomist Karl Polanyi (1983) called a market society – and new professional regulations, financial issues and a need for traceability of the quality of educational and scientific activities, from learners as well as their funders.

Temples (and laboratories) of knowledge, as well as transmission spaces, in interaction with a plethora of stakeholders, institutions are nonetheless organizations with agency capacities, employers, recipients of public subsidies, training service providers and clients – from a wide range of diversified providers.

In this context, the majority of higher education ecosystem’s stakeholders agree on the existence of positive effects of apprenticeship training on the long-term development of business productivity and, consequently, on a country’s sustainable and inclusive growth.

Historically confined to certificates of professional aptitude (CAPs), the “work-linked training” system has seen an explosion in the number of “alternating-students” (almost doubling) since the 1990s, in favor of the 1987 legislative provisions (the so-called Séguin Act), which opened up the use of “work-linked training” system to all levels of training (through pre-apprenticeship, apprenticeship or professionalization contracts). It is thought to be one of the vectors for securing employment through the professionalization of learners.

A lever of agility and vector of organizational agilization – which expresses the possible reconciliation between the company and the society, the economic world and the academic sphere, the work-linked training system, as practiced in the French higher education system – constitutes an experiential, experimental and embedded learning process by which the learner acquires distinctive professional skills through professional practice. This is conducted under the aegis of a referrer, acting both as a sponsor (tutor) and as a mentor (hierarchical). This company’s referrer is paired with a pedagogical referee from the establishment of affiliation (High School/University).

As a cooperative sponsorship system – once dear to corporations and, more recently, to solidarity-based companionship schemes – company tutoring is thought of as a means for and in practice, and for and in the sharing of experience, of acquiring the knowledge, skills and attitudes that are essential to the efficient exercise of a profession.

An apprenticeship thus outlines a new figure: that of the learner, enriching his or her “bag of skills” (theoretical, technical, operational, social and managerial) through the succession, superposition and reflective and reflexive ordering of multiple experiences, of both a formative and experimental, conceptual and practical nature.

As a transitional experience between the world of higher education and the universe of work, between the posture of the student and of the professional, work-linked training is a learning journey and an initiatory journey. It is also a powerful lever for social integration through vocational training and a vector for equal opportunities, particularly thanks to the French apprenticeship tax system. This is all the more so since, in addition to a heritage of knowledge, work-study provides the learner with know-how and interpersonal skills (including in terms of professional posture, organizational behavior and relational strategy) that increase his or her employment, which can be valued throughout his or her career path, with remuneration, both to provide support and to act as a symbol of professionalization in progress.

At the macroeconomic level, work-linked training constitutes in France a decisive factor in reducing the structural unemployment rate, especially among young people. In return, apprenticeship training is beneficial to apprentices because it allows the sedimentation of technical and behavioral skills to meet labor market requirements.

Once reserved for technical training and mainly addressing students from modest backgrounds, anxious to reduce their tuition fees while initiating a process of “professional conversion”, the work-study program has undergone a “change of identity”. Nowadays, it is popular with students, especially in prestigious business schools, and is increasingly valued by companies as a means of attracting and retaining talent.

Beyond the intrinsic and extrinsic advantages already mentioned, it is appreciated as a reducer of risk taking – for the company, as well as for the student – as a facilitator of transitions (among the different phases of life) and as an opportunity to cross more easily the first barrier of the labor market.

As a result, at the end of their theoretical and experimental training, apprentices become qualified employees who have benefited from a mechanism for the progressive transfer of academic knowledge to the professional environment and, in return, from a reflexive and critical feedback on practices from a scientific perspective. In this respect, apprentices are information brokers and transmitters (and in some cases even transcoders) of knowledge. They contribute – most often unconsciously – to increasing information fluidity among the company, the academic world and society through their hybrid (or ambidextrous) posture, as well as in promoting opportunities for meetings and exchanges, intrinsic to the apprenticeship process.

These dual training courses, both academic and embedded, mean the compatibility and complementarity of the knowledge (theoretical, methodological and equipped) that the attendance of the academic system allows them. This is a transitional process that allows a gradual shift from a (somewhat passive) student identity to a (active but critical) professional identity.

The main legacy of work-linked training lies in the sedimentation of a professional identity based on learning.

The human capital accumulated by students during the apprenticeship (both hard and soft skills acquired) is a reducing factor in unemployment, because it allows flexibility and transferability of knowledge and skills, within and between companies. The French apprenticeship market is closely linked to the traditional labor market. According to the Ministry of Labor, 50% of apprentices are recruited by their apprenticeship company, while 70% of students who have completed their apprenticeship find employment within seven months of the end of their contract2.

In this context, the geographical proximity of higher education institutions and the quality of their stakeholders’ management (with a specific focus on their relations with companies – private and public as well) are key-success factors, particularly, for business and management schools, which have made their adherence to the economic world a brand image, a distinguishing factor and a sustainable competitive advantage.

In business schools, apprenticeship training attracts a growing number of students, thanks to strategic considerations of employability, economic (reduction of tuition fees) and formative (wealth of experience and accumulated skills) considerations.

Nowadays, the capacity to offer a diverse portfolio of apprenticeship training is therefore a competitive advantage of a business school. Moreover, student satisfaction with the proposed apprenticeship is the cornerstone of business schools’ competitive strategies, due to the direct involvement of student satisfaction in the generation of financial results, and their indirect impact on national and international rankings and international labels.

More generally, the student satisfaction with apprenticeships and the porosity of training in the business world (as measured by the minimum duration of internships, the apprenticeship rate or the degree of high-level professionals in teaching profession), as well as the quality of the relationships maintained by the school and the companies in its economic ecosystem (number and type of partnerships, chairs, level of payment of the apprenticeship tax, amount of continuous training, etc.), are important and interrelated indicators of the quality of the company’s ecosystemic management.

This study proposes the use of the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) method to appreciate and evaluate the efficiency of French post-baccalaureate business schools, based on their apprenticeship training offerings and apprentices’ satisfaction with the proximity of these schools to companies. This study is original in terms of the issues it addresses and its scope of investigation. It also differs from previous research that has used the DEA method to assess the efficiency of higher education institutions. The facets of efficiency previously explored by researchers relate to teaching efficiency (Beasley 1995; Johnes 2006), research efficiency (Johnes and Johnes 1993; Beasley 1995; Abbott and Doucouliagos 2003; Sahoo et al. 2017), income efficiency (Avkiran 2001), cost efficiency (Athanassopolos and Shale 1997) and teaching quality efficiency (Avkiran 2001).

No other study has so far examined the efficiency of higher education institutions as measured by their proximity to the business world, as shown by student satisfaction with this criterion and the level of learning in training. Our results tend to confirm the strong intertwining of the proven proximity of schools to the economic world, the effective apprenticeship practice (number and diversity of contracts) and the level of student satisfaction in terms of employability.

5.1.2. Student satisfaction through apprenticeship training

Operating in a highly competitive environment, business schools consider the student satisfaction indicator the most important barometer, reflecting both financial and non-financial performances. The relationship between student satisfaction and performance is both synchronous and delayed.

The rating of French business schools by students is essentially based on meeting their expectations in regard to the quality of the offered services. It is measured by internal and, sometimes, external questionnaires or surveys (administered by evaluation agencies or ranking institutes). An educational or pedagogical experience (considered satisfactory and sufficient) is a multidimensional construct, as it is influenced by several specific interrelated factors (interpersonal, intrapersonal, academic and environmental).

Conceptually, student satisfaction reflects a favorable cognitive state due to a positive evaluation of the educational experience (Athiyaman 1997). In other words, a student is satisfied when the educational service set up by the business school meets his or her expectations (Szymanski and Henard 2001). However, meeting diverse and varied expectations (and being subject to a variable hierarchy from one actor to another) is a major challenge. Especially since the expectations to be met are not only those of the learners themselves, but also those of their funders (most often parents), as well as of companies, which can contribute to the management of their training and are, above all, their future employers.

A student’s expectations are not fixed, but are constantly changing and adjusting, during his or her schooling to his or her academic, social, physical and even spiritual needs (Lee and Jang 2015), not to mention the students’ sensitivity to mimetic (and gregarious) effects, and the impact of context and conjuncture on the formulation of personal, as well as professional expectations and projects. Student satisfaction should therefore be seen as a global symptom that embodies a general feeling towards a chain of educational experiences (Bolton et al. 2000).

Many factors affect student satisfaction. Traditionally, the reputation of the programs; the “market recognition” of the degree; the quality of teaching; the social relations among students and staff; the relations among students themselves; the alignment of the institution with the values it promotes; and the congruence between personal axiology and institutional culture are considered to be factors reflecting the satisfaction and dissatisfaction that affect the willingness of students to stay or not in their schools.

In addition to these traditional factors, the effects of the economic crisis and its repercussions on the labor market, in terms of unemployment (more significant among young people) and increasing precariousness, led to new students’ expectations. In France, job creation – which is recovering slowly, as a result of weak economic growth – remains insufficient to resorb the unemployment rate, with, as a consequence, an increase in job vulnerability, situations of precarity and the rise of the number of poorer workers.

At the same time, the labor market is becoming increasingly competitive and competition is now spreading worldwide; pushing for a “cost killing” race, lower labor costs and a reduction in the social rights and benefits acquired over the centuries. In this context, apprenticeship training becomes a significant professional background because it strengthens students’ employability and ensures better professional integration, while stabilizing and “acculturating” newcomers to the labor market.

Apprenticeship training – a new proposal in addition to the many educational services offered by business schools – has therefore emerged as an additional expectation, able to contributing to student satisfaction… and to the needs of companies, at the same time as joining (and symbolizing) this promise of “mobility” that is not only intellectual but also spatial, cultural and social.

5.2. Methodology

5.2.1. Using the DEA method in measuring the efficiency of higher education institutions

The DEA method has been applied in different fields and industries such as health (Fragkiadakis et al. 2016; Rouyendegh et al. 2016), environment (Lozano 2015; Zhao et al. 2016), financial risk (Tsolas and Charles 2015; Chen et al. 2017) and industry (Hailu and Tone 2017). The education sector in general and the higher education sector, in particular, have drawn the attention of researchers to the application of the DEA method to evaluate the efficiency of schools and universities. Early studies of the efficiency of higher education institutions focused on Anglo-Saxon countries such as the United States, Great Britain and Canada (Bessent et al. 1983; Ahn et al. 1988; Tomkins and Green 1988). Since the 2000s, the DEA method has been widely disseminated to the international academic community, and widely adopted as a robust method for measuring the efficiency and benchmarking of universities and business schools. Examples include studies by Agasisti and Bianco (2006) in Italy; Ruiz et al. (2015) in Spain; Abbott and Doucouliagos (2003) and Avkiran (2001) in Australia; Bougnol and Dulá (2006), Colbert et al. (2000) and Ray and Jeon (2008) in the United States; Bhattacharyya and Chakraborty (2014), Debnath and Shankar (2009), Sahoo et al. (2017) and Sunitha and Duraisamy (2013) in India; Kao and Hung (2008) in Taiwan; Tran and Villano (2015) in Vietnam; Wang (2019) in China, Wolszczak-Derlacz (2017) in Europe and the United States, etc.

5.2.2. Presentation of the DEA method

DEA is a mathematical operational research tool for benchmarking and evaluating the efficiency of Decision Making Units (DMUs) (business schools, in our case) by converting a set of inputs into a set of outputs. The purpose of the DEA method is to form an efficient frontier that determines a space of best practices between the DMUs. The advantage of using DEA is twofold. First, the DEA is a non-parametric method. Consequently, it does not impose any functional form concerning the production process of business schools. DEA thereby allows the simultaneous use of inputs and outputs of different natures, and measured by different units of measurement. For example, business schools provide professors, technical and administrative staff, premises and a research budget, which will be used to produce a quantity of research articles, knowledge transfer, quality training, student satisfaction, notoriety, etc.

DEA identifies inefficient business schools (with a score of less than 1) and those with best practices (business schools with a score equal to one) in the sector that should serve as a model for other institutions.

In general, there are two main models. The first is the CCR model, developed by Charnes, Cooper and Rhodes (1978): it is based on the assumption of constant returns to scale (CRS) and estimates an overall technical efficiency for each DMU. The second is the BCC model, developed by Banker, Charnes and Cooper (1984): it operates with “variable returns to scale” and estimates pure technical efficiency, which represents the relationship between the overall technical efficiency and returns to scale. In addition, the DEA models are also separated by their objectives into input-oriented and output-oriented models. The objective of an input-oriented DEA model is to minimize inputs by assuming constant outputs, while maximizing outputs (keeping inputs constant) is the objective of output-oriented DEA models.

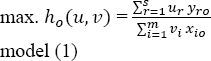

Assuming that there are n DMUs or companies, each with m inputs and s outputs, the efficiency score of a ho DMU is obtained by solving the following CRC program, proposed by Charnes, Cooper and Rhodes (1978):

under duress:

ur, vr ≥ 0, with ur, vr being the weighting systems to be determined.

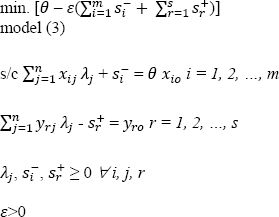

The previous theoretical CCR model can be transformed into a linear program, where the excesses in inputs and outputs are taken into account, using the Charnes–Cooper transformation. We therefore have the following equivalent form:

The dual linear program (envelopment program) of model 2 is as follows:

where:

- – θ*: the optimal solution;

- – θ: the efficiency score;

- – λ : the vector of constants;

- – ε : an infinitesimal non-Archimedean constant.

Therefore, based on the concept of relative efficiency, two definitions can be adopted. A DMU is totally efficient if, and only if, θ*=1 and all slacks excesses are equal to zero. That is to say, ![]() A DMU is weakly efficient if, and only if, θ*=1 and

A DMU is weakly efficient if, and only if, θ*=1 and ![]() and/or

and/or ![]()

5.2.3. Application of the DEA method to business schools in France

In this section, the DEA method is adopted to evaluate the efficiency of French post-baccalaureate business schools, based on their apprenticeship training offerings and the satisfaction of apprentices with the proximity of these business schools to companies. We apply the results of the annual survey of L’Étudiant, which ranks French business schools according to several thematic criteria.

Since the indicators from the L’Étudiant survey address performance results can be seen as outputs in the DEA method, and since we do not have homogeneous input indicators on business schools, we apply the DEA version with a unique and constant input, having the value of 1 for all business schools. This DEA version has been recommended for the measurement of multidimensional composite indicators to overcome the problem of aggregating and weighting single and individual indicators (Lovell and Pastor 1999; Zhou et al. 2007; Yang et al. 2014). In addition, in order to provide better discrimination and ranking between efficient business schools (with an efficiency score of 1), we will retain the super-efficiency scores. We therefore apply the output-oriented CCR model.

Proximity to companies is measured by two indicators: the percentage of students on apprenticeship or professionalization contracts in 2017–2018, and the minimum duration of internships and assignments during the curriculum in 2017–2018. As for student satisfaction with their apprenticeship, we have chosen the following indicators: student’s satisfaction (2014–2017 promotion-year) about the school’s relationship with partner companies, student satisfaction with their preparation for professional life and student satisfaction with their support in carrying out their professional projects.

5.2.4. Result of the DEA method

Table 5.1 presents the efficiency scores of French post-baccalaureate business schools following the use of Model 3, presented above.

Table 5.1. Efficiency scores of French post-baccalaureate business schools

| Business School | CCR model – score of super-efficiency |

| ICD, Paris, Toulouse | 1.4318 |

| IPAG, Paris, Nice | 1.1632 |

| CESEM – NEOMA BS, Reims | 1.0714 |

| EMLV, Paris la Défense | 1.0462 |

| ESSEC Global BBA, Cergy | 1.0167 |

| IESEG, Lille, Paris | 1.0159 |

| PSB, Paris | 1.0148 |

| EM Normandie, Le Havre, Caen, Paris | 1.0051 |

| BBA INSEEC, Bordeaux, Lyon | 1.0048 |

| ESSCA, Angers, Paris, Aix-en-Provence, Lyon, Bordeaux | 1 |

| EDC, Paris BS | 0.9828 |

| Global BBA – NEOMA BS, Rouen, Reims3 | 0.9767 |

| TEMA – NEOMA BS, Reims | 0.9767 |

| BBA EDHEC, Lille, Nice | 0.9767 |

| EBP International – KEDGE BS, Bordeaux4 | 0.9655 |

| ESCE, Paris, Lyon | 0.9535 |

| ESAM, Paris, Lyon, Toulouse | 0.9453 |

| BBA La Rochelle – ESC La Rochelle | 0.9363 |

| EBS Paris | 0.907 |

| International BBA – KEDGE BS, Marseille | 0.892 |

| IDRAC BS, Lyon | 0.8638 |

| BBA SCBS – Groupe ESC Troyes | 0.8621 |

| BBA in Global Management – SKEMA BS, Sophia-Antipolis | 0.8605 |

According to Table 5.1, the analysis of the efficiency of French post-baccalauretate business schools – in terms of proximity to companies and student satisfaction – reveals that the best positioned schools in terms of efficiency are those that culturally and structurally encourage apprenticeship practice, through the opening of ad hoc training (ICD) or through a rational arrangement of time tables and work/study schedules (IPAG Business School, EMLV, IESEG). These institutions are classified here through their flagship training: the Grande École program, which is spread over five academic years. However, indicators such as the minimum duration of internships or the volume of work-study programs remain sensitive to the duration and organization of training. As a result, regarding the efficiency that is measured in terms of student satisfaction, the integrated post-baccalaureate programs are the most successful (ICD, IPAG Business School, EMLV, IESEG, etc.).

Moreover, institutions with a higher societal awareness, anchored in a “service to society” perspective, as shown by ecosystem-based stakeholder management, obtain a better measure of efficiency. Twelve of the 24 schools studied have therefore obtained an EESPIG label (private non-profit institutions under contract with the state) and, among them, five are at the top of the ranking, among the “super-efficient” schools, while one has a full efficiency score and three others are almost efficient.

However, the reputation effect supports the schools whose courses (Grand École program of Bachelor’s degree in Business Administration) are well established in the French academic landscape and show social sensitivity, such as the ESSEC Business School or NEOMA. The notoriety effect can be appreciated as a signal of the school’s proximity to companies, and its commitment to the strategic and inclusive management of its stakeholders. This contributes not only to the development of work-study programs, but also to student satisfaction in terms of the school’s adherence to the economic environment.

The reputation of the establishments is also confirmed by their alignment with the most demanding national and international standards. This is the case for ESSEC Business School (AACSB, EQUIS, AMBA), NEOMA (EQUIS, AMBA, AACSB) and IESEG (AACSB, EQUIS, AMBA). It is interesting to note that these institutions have quality accreditation for all their curricula, including their short courses (BBA). In addition, the reputation and labeling effect is maximum for the short courses (considered more professionalizing) of the most renowned and accredited schools.

In addition, there is a tendency to reward “rising” Grandes Écoles in national and international rankings, and those engaged in accreditation processes, promoting both the structuring of their organizational processes, the readability of their educational curriculum and the quality monitoring of their training and scientific activities, as well as the strengthening of their adherence to ecosystems, towards their internal (employees and especially students) and external (companies, local communities, public authorities, society) stakeholders. This is the case with the IPAG Business School, which recently obtained its EPAS accreditation (2018) and its AACSB eligibility, with EMLV and PSB, which are also involved in accreditation procedures.

Lastly, geographical centrality is a bonus, the geographical proximity being a factor favoring the proximity of schools to dynamic economic environments (potential internship and work-study providers and employability vectors for graduates due to the porosity of the environment) and, consequently, the volume of work-study contracts.

Consequently, all “super-efficient” or “efficient” schools have campuses in Paris (ICD, IPAG Business School, IESEG, PSB, EM Normandie, ESSCA, INSEEC) or in the Paris region (ESSEC, EMLV), or in relative proximity to the capital (NEOMA).

Among the schools with an efficiency score lower than 1, and therefore analyzed as inefficient in relation to the criteria studied, it appears that only four out of 13 have a Parisian campus. However, these four institutions appear to have little accreditation or even none of the main international labels (AACSB, EPAS, EQUIS, AMBA).

5.3. Conclusion

This exploratory empirical survey underlines that the efficiency of post-baccalaureate business school training programs – analyzed in terms of their proximity to the economic environment and the level of student satisfaction – is highly sensitive to the effects of engagement, as shown by the company’s appreciation of the apprenticeship system, the modularity of the training and the minimum duration of the professional experience during this course.

This engagement effect is strongly influenced by the cultural and geographical proximity of institutions to companies, which is both an identity marker (commitment to society, involvement in ecosystem management, as demonstrated by the award of an EESPIG label to six of the 10 “super-efficient” schools) and a differentiating factor in the increasingly competitive business school market.

However, this engagement effect is moderated by a reputation effect, based on the notoriety of the training institutions and therefore the confidence shown by companies in the value of their graduates and their diplomas, and the quality of both as assessed through international accreditation.

The social embedding of higher education institutions in their economic ecosystem is largely due to their geographical location and, more specifically, their strategy of opening and maintaining campuses. Schools far from the capital and without campuses in the Paris region (or nearby) therefore show an adherence to the economic market, revealed by a lower volume of work-study contracts signed, a shorter minimum duration of internships and a lower level of student satisfaction with their employability.

As “accelerators of employability” and “vectors for equal opportunities”, work-study programs are thus proving to be a powerful lever for social efficiency in French business and management schools.

Alternately, a factor of strategic differentiation and a sustainable competitive advantage, work-linked training constitutes a paradigmatic case of individual flexibility, as well as an initiatory (and experiential) journey towards an agile professionalism and a postural learning.

5.4. References

Abbott, M. and Doucouliagos, C. (2003). The efficiency of Australian universities: A data envelopment analysis. Economics of Education Review, 22(1), 89–97.

Agasisti, T. and Dal Bianco, A. (2006). Data envelopment analysis to the Italian university system: Theoretical issues and policy implications. International Journal of Business Performance Management, 8(4), 344–367.

Ahn, T., Charnes, A., and Cooper, W.W. (1988). Some statistical and DEA evaluations of relative efficiencies of public and private institutions of higher learning. Socio-economic Planning Sciences, 22(6), 259–269.

Athanassopoulos, A.D. and Shale, E. (1997). Assessing the comparative efficiency of higher education institutions in the UK by the means of data envelopment analysis. Education Economics, 5(2), 117–134.

Athiyaman, A. (1997). Linking student satisfaction and service quality perceptions: The case of university education. European Journal of Marketing, 31(7), 528–540.

Avkiran, N.K. (2001). Investigating technical and scale efficiencies of Australian universities through data envelopment analysis. Socio-economic Planning Sciences, 35(1), 57–80.

Banker, R.D., Charnes, A., and Cooper, W.W. (1984). Some models for estimating technical and scale inefficiencies in data envelopment analysis. Management Science, 30(9), 1078–1092.

Beasley, J.E. (1995). Determining teaching and research efficiencies. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 46(4), 441–452.

Bessent, A.M., Bessent, E.W., Charnes, A., Cooper, W.W., and Thorogood, N.C. (1983). Evaluation of educational program proposals by means of DEA. Educational Administration Quarterly, 19(2), 82–107.

Bhattacharyya, A. and Chakraborty, S. (2014). A DEA-TOPSIS-based approach for performance evaluation of Indian technical institutes. Decision Science Letters, 3(3), 397–410.

Bolton, R.N., Kannan, P.K., and Bramlett, M.D. (2000). Implications of loyalty program membership and service experiences for customer retention and value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 95–108.

Bougnol, M.L. and Dulá, J.H. (2006). Validating DEA as a ranking tool: An application of DEA to assess performance in higher education. Annals of Operations Research, 145(1), 339–365.

Cahuc, P. and Ferracci, M. (2015). L’évolution de l’alternance en France. L’apprentissage. Sécuriser l’emploi, 15–24.

Charnes, A., Cooper, W.W., and Rhodes, E. (1978). Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. European Journal of Operational Research, 2(6), 429–444.

Chen, W., Gai, Y., and Gupta, P. (2018). Efficiency evaluation of fuzzy portfolio in different risk measures via DEA. Annals of Operations Research, 269(1/2), 103–127.

Colbert, A., Levary, R.R., and Shaner, M. C. (2000). Determining the relative efficiency of MBA programs using DEA. European Journal of Operational Research, 125(3), 656–669.

Fragkiadakis, G., Doumpos, M., Zopounidis, C., and Germain, C. (2016). Operational and economic efficiency analysis of public hospitals in Greece. Annals of Operations Research, 247(2), 787–806.

Hailu, K.B. and Tone, K. (2017). Setting handicaps to industrial sectors in DEA illustrated by Ethiopian industry. Annals of Operations Research, 248(1/2), 189–207.

Johnes, J. (2006). Data envelopment analysis and its application to the measurement of efficiency in higher education. Economics of Education Review, 25(3), 273–288.

Johnes, G. and Johnes, J. (1993). Measuring the research performance of UK economics departments: An application of data envelopment analysis. Oxford Economic Papers, 332–347.

Kao, C. and Hung, H.T. (2008). Efficiency analysis of university departments: An empirical study. Omega, 36(4), 653–664.

Lee, J. and Jang, S. (2015). An exploration of stress and satisfaction in college students. Services Marketing Quarterly, 36(3), 245–260.

Lovell, C.K. and Pastor, J.T. (1999). Radial DEA models without inputs or without outputs. European Journal of Operational Research, 118(1), 46–51.

Lozano, S. (2015). A joint-inputs Network DEA approach to production and pollutiongenerating technologies. Expert Systems with Applications, 42(21), 7960–7968.

Mitra Debnath, R. and Shankar, R. (2009). Assessing performance of management institutions: An application of data envelopment analysis. The TQM Journal, 21(1), 20–33.

Polanyi, K. (1983). La Grande Transformation. Gallimard, Paris.

Ray, S.C. and Jeon, Y. (2008). Reputation and efficiency: A non-parametric assessment of America’s top-rated MBA programs. European Journal of Operational Research, 189(1), 245–268.

Rouyendegh, B.D., Oztekin, A., Ekong, J., and Dag, A. (2016). Measuring the efficiency of hospitals: A fully-ranking DEA–FAHP approach. Annals of Operations Research, Springer, Berlin, 1–18.

Ruiz, J.L., Segura, J.V., and Sirvent, I. (2015). Benchmarking and target setting with expert preferences: An application to the evaluation of educational performance of Spanish universities. European Journal of Operational Research, 242(2), 594–605.

Sahoo, B.K., Singh, R., Mishra, B., and Sankaran, K. (2017). Research productivity in management schools of India during 1968-2015: A directional benefit-of-doubt model analysis. Omega, 66, 118–139.

Sunitha, S. and Duraisamy, M. (2013). Human capital and development. In Measuring Efficiency of Technical Education Institutions in Kerala Using Data Envelopment Analysis, Siddharthan, N. and Narayanan, K. (eds). Springer, New Delhi, 129–145.

Szymanski, D.M. and Henard, D.H. (2001). Customer satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29(1), 16–35.

Tomkins, C. and Green, R. (1988). An experiment in the use of data envelopment analysis for evaluating the efficiency of UK university departments of accounting. Financial Accountability & Management, 4(2), 147–164.

Tran, C.D.T. and Villano, R.A. (2018). Measuring efficiency of Vietnamese public colleges: An application of the DEA-based dynamic network approach. International Transactions in Operational Research, 25(2), 683–703.

Tsolas, I.E. and Charles, V. (2015). Incorporating risk into bank efficiency: A satisficing DEA approach to assess the Greek banking crisis. Expert Systems with Applications, 42(7), 3491–3500.

Wang, D.D. (2019). Performance-based resource allocation for higher education institutions in China. Socio-economic Planning Sciences, 65, 66–75.

Wolszczak-Derlacz, J. (2017). An evaluation and explanation of (in) efficiency in higher education institutions in Europe and the US with the application of two-stage semi-parametric DEA. Research Policy, 46(9), 1595–1605.

Yang, G., Shen, W., Zhang, D., and Liu, W. (2014). Extended utility and DEA models without explicit input. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 65(8), 1212–1220.

Zhao, L., Zha, Y., Wei, K., and Liang, L. (2017). A target-based method for energy saving and carbon emissions reduction in China based on environmental data envelopment analysis. Annals of Operations Research, 255(1/2), 277–300.

Zhou, P., Ang, B.W., and Poh, K.L. (2007). A mathematical programming approach to constructing composite indicators. Ecological Economics, 62(2), 291–297.

Chapter written by Maria-Giuseppina BRUNA and Béchir BEN LAHOUEL.

- 1 According to Karl Polanyi (1983), a market society emerges when the market imposes its laws on the institutions of social life, through a process of disenfranchisement, leading to a progressive market grip – and its self-regulatory myth – on the functioning of society and not only on the mechanisms for organizing economic activities. The market is here thought of as an institution that regulates both the business world and the world’s business.

- 2 Interview organized on May 17, 2018 with Les Échos START by Minister of Labor Muriel Pénicaud on the occasion of the 8th edition of the Fête de l’alternance, where she defended her bill on apprenticeship reform.

- 3 NEOMA features in the post-baccalaureate ranking in L’Étudiant with two different degrees.

- 4 KEDGE features in the post-baccalaureate ranking in L’Étudiant with two different degrees.