Methods of instruction

Abstract:

This chapter provides a brief summary of what information literacy instruction (ILI) is and what it has become in most academic libraries, describing the evolution of ILI from its conception in academic library education to the marketing tool it has developed into over the years. The chapter also defines the many forms available in academic libraries today. It outlines the different modes of instruction including traditional lecture/demonstration, active learning, computer-assisted, learner-centered and self-directed.

information literacy instruction

active learning instruction (AL)

computer assisted instruction (CAI)

What is information literacy instruction?

To describe the different methods of information literacy instruction first requires a definition of what it is. This chapter does not attempt to define information literacy yet again; there is already more than enough delineation of the term. With so many definitions for information literacy, it is amazing that anyone is able to apply it to instruction. Despite Owusu-Ansah’s plea for an end to the search (Owusu-Ansah, 2004) for a definition, the debate continues. Librarians have been attempting to re-clarify the definition since the ALA produced its adequate and clear demarcation of the concept in 1989. The ALA described information literacy as a participant skill set that included recognizing an information need and locating, evaluating and using the needed information effectively (American Library Association Presidential Committee on Information Literacy, 1989). This simple set of skills has been re-conceptualized and so elaborated upon that it is hardly recognizable.

There have been many efforts to clarify the ALA’s definition, adding pedagogical and conceptual advancements. Christina Doyle presented specific attributes requiring certain competencies and attached them to the process of finding, evaluating, and using information (Doyle, 1992). Carol Kuhlthau believed information literacy is a learning process and incorporated the skill set into six stages of an instructional model (1993). Christine Bruce developed a relational model presenting seven different experiences a participant encounters through information literacy (Bruce, 1997). Then there are the granddaddies of all definitions, the offerings from the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) and the American Association of School Librarians (AASL). These organizations created standards from the skill set, and added performance indicators and behavioral outcomes to develop an all inclusive definition. All of these definitional efforts have established the basis for what an information literate person is, though there has been limited expansion on the find-evaluate-use principles the ALA presented in their 1989 Final Report.

There has been enough debate on defining information literacy. Owusu-Ansah was right when proclaiming ‘enough is enough’ (Owusu-Ansah, 2005) when referring to the accumulated literature defining information literacy. All the above mentioned proponents have clarified what information literacy is and what skills an information literate person should possess. Efforts should now focus on how to effectively implement this knowledge into methods of instruction to promote information literacy. Literacy by nature is a continuum, changing as an individual’s goals change. Grassian and Kaplowitz claimed there is no standard definition for the term: they believe that information literacy means different things to different people and can vary from situation to situation (Grassian and Kaplowitz, 2001). This is true and highlights the importance of choosing an effective method of instruction, depending on the participant and the place. The participants’ ideas of being information literate are a major consideration in defining information literacy and the ideas change over time and environment. So there will be no new definition or re-conceptualization trotted out here. For the premise of this book the ALA’s original simple skill set will suffice: information literacy is defined as finding, evaluating, and using information effectively; and information literacy instruction (ILI) is teaching these skills depending on who is being taught and where the instruction takes place.

Information literacy instruction: what has it become?

Academic librarians in the United States have been using instruction to teach participants about information for more than a century. The ideas and concepts ILI is based on were developed in the late nineteenth century. Melvin Dewey changed librarianship from a vocation to a profession in that period and at about the same time wrote an article comparing the library to a school and claimed librarians were ‘in the highest sense teachers’ (Dewey, 1876). Though Dewey most likely made these comparisons metaphorically, the origins of library instruction in U.S. academic libraries began to appear shortly after his 1876 article.

The late nineteenth century saw an expansion of the academic library, growing from a small campus library to the large institutions and centers of academic infrastructure found on university campuses today (Hardesty, Scmitt, and Tucker, 1986). The larger facilities developed bigger, more complex collections creating a need for instruction on their use (Lorenzen, 2001). During the last decades of the century and the first half of the twentieth century many universities, including Harvard, University of Michigan, Georgetown and Oberlin, began offering courses in library and information use. During this time many academic librarians conducted research on library instruction and implemented the subject into curriculums from full semester for-credit courses to integrated single class lectures. Although pioneers of academic library instruction from this early period laid the foundations for ILI, academic library instruction did not fully develop in academic librarianship until the 1960s.

Patricia Knapp’s work combining librarianship with instruction in the early 1960s started a formalized movement and brought instruction to the forefront in academic libraries. Knapp believed that library instruction should be essential to college curriculums, and her competency tests and instructional assignments continue to provide direction for today’s instructional librarians (Grassian and Kaplowitz, 2001). Knapp’s efforts at bibliographic instruction blossomed into the modern instructional movement that became ubiquitous in academic and school libraries in the 1980s and 1990s. Patricia Breivik redefined library instruction as information literacy while chairing the ALA Presidential

Committee on Information Literacy which presented the find, evaluating and use definition in 1989 (Grassian and Kaplowitz, 2009). The committee did not see the concept restricted to libraries and, driven by technological progress and the explosion of information, ILI expanded. Formalized ILI programs began appearing outside of academic institutions in public and special libraries.

According to Grassian and Kaplowitz, these formalized programs forked into two branches of instruction, synchronous and asynchronous. Asynchronous is a term used to describe anytime–anyplace instruction and is delivered through workbooks or online tutorials. Synchronous is real-time face-to-face instruction, usually delivered to groups and commonly in one-shot, one-hour lectures. These one-time instructional sessions have become the most popular delivery method of ILI. ‘One-shots’ are a marketing tool rather than anything else. Librarians are not teaching when they are invited to perform a one-class period lecture on the use of the library and its resources; they are marketing. Susan Ardis, an experienced library instructor and Head of the Science and Engineering Libraries Division at the University of Texas Libraries, believes ILI has become strictly a practice of marketing. She claims, ‘Information literacy instruction as it is typically practiced today is not truly teaching. Rather, it is a form of marketing where the action takes place in a classroom and librarians are guest lecturers demonstrating and marketing our resources, expertise, and utility. This activity is marketing’ (Ardis, 2005). Presenting new resources in an orientation is like introducing new products to a target market. New student and new faculty orientations are similar to entering new market territories. Table 1.1 makes the point by comparing basic marketing goals with those of library instruction.

Table 1.1

Marketing/information literacy comparison

| Marketing | Information literacy/bibliographic instruction |

| Introduce new products | Introduce new library services/tools |

| Extend or regain market for existing products | Extend usage of library tools |

| Enter new territories | Inform new students/faculty |

| Boost sales of a particular product | Increase usage of a particular tool or service |

| Cross-sell or bundle one product with another | Demonstrate how specific tools and services work together—e.g. EI and INSPEC |

| Refine a product | Improve reference services |

Source: Ardis (2005)

Librarians have their most extensive contact with students through ILI sessions and in many cases, other than reference interviews, ILI is their only student contact opportunity. Ardis describes the one-shot ILI as a chance to sell the library’s products to a large group of ‘pre-qualified customers.’ Barbara Kenney, an instructional librarian from Roger Williams University, also believes the goal of basic ILI now is marketing. She claims, ‘The ultimate goal of a one-shot information literacy session is to have students actively engage with the librarians and library resources in order to provide a glimpse into the many ways the library supports student learning. In short, the librarians are building a customer base through a skillful marketing enterprise’ (Kenney, 2008). Over the past fifty years library instruction has morphed from its humble beginnings as bibliographic instruction to information literacy instruction. In recent years its conceptualization has also somewhat changed; the learning paradigm is still based on critical thinking skills, but librarians are more often promoting the library and its resources in ILI sessions than trying to develop information literate students.

Teaching methods

There is no shortage of offerings when it comes to information literacy instruction. The availability has been described as a ‘smorgasbord groaning with an array of choices’ (Grassian and Kaplowitz, 2001). Selecting an effective method can be difficult when faced with this surfeit, and an awareness of what is available is the first step before ordering from the extensive menu. From active learning to web-based tutorials, determining the best solution can be confusing without some knowledge of the ingredients. Instruction represents a wide range of topics and the most common areas for instruction are conducting library research and research strategies, using the catalog, using reference tools, an overview of the library and its resources, literature searching, and using computerized or electronic resources. Contact times are varied and can range from 15 minutes to full class sessions across an entire semester though the most common instructional period is the traditional one hour class period. Delivery modes also vary widely – passive, interactive, asynchronous, synchronous, face-to-face, remotely, online, and any combination of these forms. These topics, contact times and delivery modes can be blended in any number of ways to design a teaching method. However, instructional methods usually fall into one of five categories: traditional lecture, active learning, computerassisted instruction, learner-centered instruction and self-directed independent learning (see Table 1.2).

Table 1.2

| Traditional instruction (TI) | Instructional material is transmitted to students from teachers, and is a passive method of learning for students. (Lecture–demonstration) |

| Active learning (AL) | Students are actively engaged in their own learning, with the instructor taking on a facilitation role. (Problem-based learning) |

| Computer-assisted instruction (CAI) | A computer is used to deliver the instruction directly to the student. (Web-based tutorials) |

| Learner-centered instruction (LCI) | Focus is on the individual student’s unique learning needs. (Individual term paper counseling) |

| Self-directed, independent learning (SDIL) | Learning in which the individual has primary responsibility for his or her education. (Workbooks) |

Traditional instruction (TI)

The traditional lecture–demonstration method has been widely used in every field of education, and traditional instruction has become the most popular teaching method for information literacy programs. It favors the long established custom of teacher-centered instruction where the instructor talks and the learners listen. It is favored by most librarians because of the popularity of the ‘one-shot’ single class period instructional sessions. Librarians are limited by time constraints and the lecture method seems most appropriate to deliver all the information in the short time allotted for their instruction periods. Perhaps the greatest advantage of the lecture method is control. The librarian has control over the aim, content, organization, pace, and direction of the presentation. The lecture can also facilitate any class size and is ideal for large-class communication. The fundamental problem with lecture–demonstration is that the method is not student-centered. The lecture method places students in a passive role and this has been proven to hinder student learning. It encourages one-sided communication and the instructor must make extra effort to identify student problems and student understanding of content.

Traditional instruction is developed based on numerous factors, including audience, course nature and curriculum, class assignments, class settings, availability of instructional tools, and instructor needs. Project specific information competence instruction and instructor collaboration have a great influence on traditional instruction. The librarian collaborates with instructors to target specific classes and class assignments in the development of the lecture–demonstration for each class orientation. The instructor communicates to the librarian the objectives of the class and the major assignments requiring research. The librarian designs a curriculum to inform the students on use of the library and highlights the library resources that would contribute to completion of the class assignments. The lecture–demonstration is usually delivered in a mediated classroom equipped with a computer, projector, and projection screen. The lecture method supports a simple outcome-based approach that is effective in the onetime instructional periods a librarian typically has with students. Here is a list of common learning outcomes a librarian may attempt to achieve with the one-shot traditional lecture instruction:

1. Increase knowledge of library and library resources

2. Understand contents and functions of specific databases

3. Search databases using efficient search terms

5. Find peer reviewed articles

6. Find books and articles in the library. (Weisskirch, 2007)

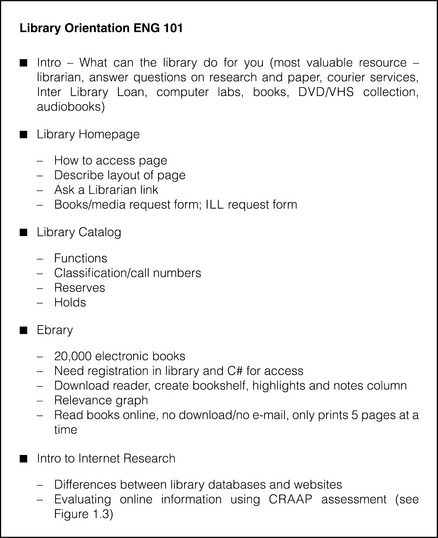

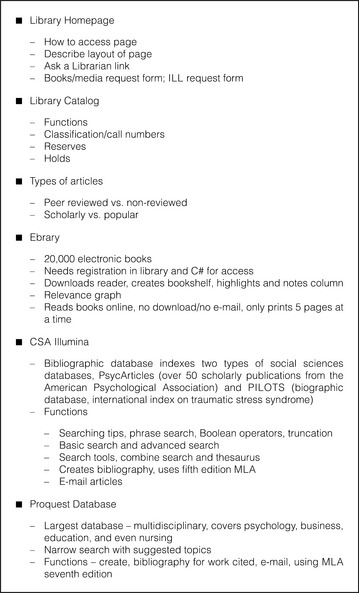

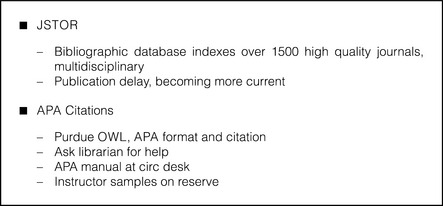

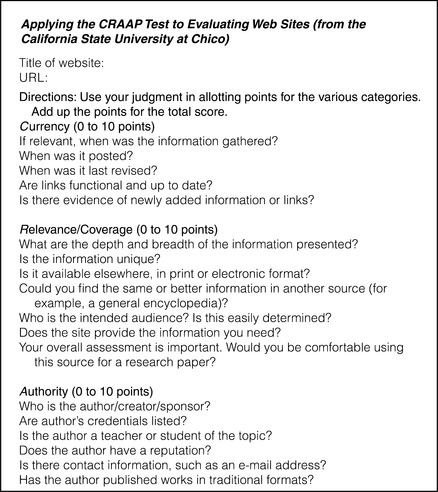

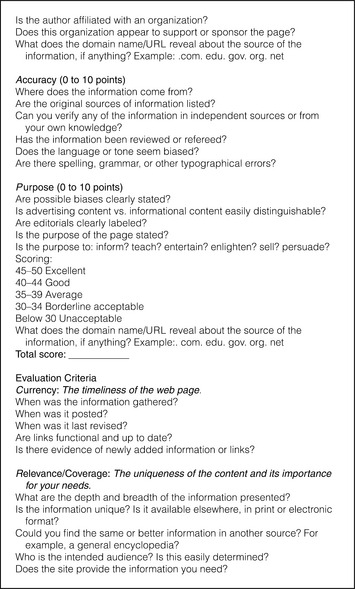

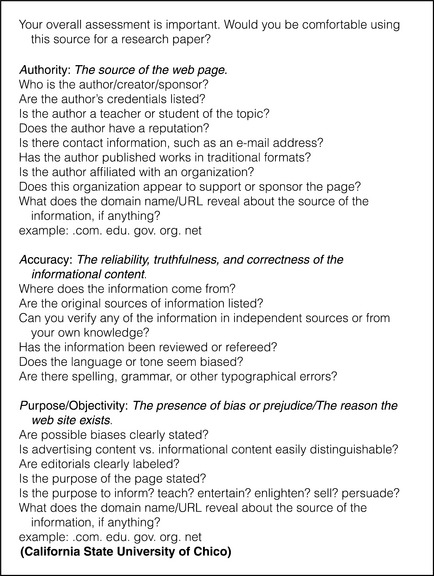

Content of a one-shot ILI session could include a presentation on what the library can do for the students, and a tour of the library’s web page, highlighting the catalog and bibliographic databases. Additionally, there can be a introduction to citation generators, resources to assist in different writing and citation styles (MLA, APA, and others), and information on the evaluation of websites. Figures 1.1 and 1.2 provide a basic ILI curriculum for an ENG 101 class and a PSY 101 class. Figure 1.3 is a form used by the California State University at Chico Libraries for evaluating web-based information.

With the advent of technology and the Internet, the lecture method is no longer confined to a synchronous, face-to-face format. Now lectures can be recorded and delivered via a DVD or over the Internet through streaming media to students at any time. Though streaming video is a web based method of instruction and has long been considered part of computer assisted instruction (CAI), here it will be classified with traditional instruction because the content of most videos is lecture and demonstration by some type of instructor. Streaming media and delivering instruction through DVD can be more efficient and more effective than traditional face-to-face sessions. Research studies have shown that students who received video instruction recalled more information than students who received the same instructional content through the traditional face-to-face lecture method (Bennett et al., 2009). Streaming media is a web-delivered audio-video presentation that participants can view and download simultaneously on their own computers. Video instruction lets the student learn whenever they want and also allows the participant to view the instruction as many times as necessary.

Preparing video instruction is more complicated than developing a traditional face-to-face lecture to be delivered in a classroom. The process requires recording, editing, digitizing and delivery technology. Recording equipment consists of a camera, camera support, microphone, lighting, and studio. The cameras can be expensive and cost tens of thousands of dollars, but any consumer-grade camcorder or digital video camera will get the job done. A good sturdy tripod for support can be purchased at any camera store. If possible do not use the camcorder’s built-in microphone: for best audio results purchase a wireless remote microphone that can be worn on the speaker’s lapel. The video can be shot on location in the library, or a studio setting with fixed lighting will provide a much higher quality video. If the library does not have its own video department, it is inexpensive to rent a TV studio. There are numerous editing and digitizing softwares available, from expensive Avid Xpress to Adobe Photoshop Elements 1.0 and Jasc Paint Shop. To render the video in streaming format Microsoft Windows Media Encoder can be downloaded for free and used, and for delivery a web server to store the video is required (Cox and Pratt, 2002). In addition to the technology needed, there are other factors to consider when developing video instruction. First, keep the demonstrations short. Internet participants can exit with the click of a mouse and studies of participant behavior have shown they will do so unhesitatingly with anything they find uninteresting or difficult, so multiple short segments of three to four minutes will be more effective than a long detailed video (Crowther and Wallace, 2001). Content should be carefully scripted so the narration is brief, direct and descriptive. Colorful graphics and entertaining delivery also go a long way to keeping participants interested.

Whether choosing the face-to-face traditional lecture or video, both offer different advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages of traditional lecture

![]() gives the instructor the chance to expose students to unpublished or not readily available material;

gives the instructor the chance to expose students to unpublished or not readily available material;

![]() allows the instructor to precisely determine the aims, content, organization, pace, and direction of a presentation; In contrast, more student-centered methods, e.g., discussions or laboratories, require the instructor to deal with unanticipated student ideas, questions, and comments;

allows the instructor to precisely determine the aims, content, organization, pace, and direction of a presentation; In contrast, more student-centered methods, e.g., discussions or laboratories, require the instructor to deal with unanticipated student ideas, questions, and comments;

![]() can be used to arouse interest in a subject;

can be used to arouse interest in a subject;

![]() can complement and clarify text material;

can complement and clarify text material;

![]() complements certain individual learning preferences. Some students depend upon the structure provided by highly teacher-centered methods;

complements certain individual learning preferences. Some students depend upon the structure provided by highly teacher-centered methods;

Disadvantages of traditional lecture

![]() places students in a passive rather than an active role, which hinders learning;

places students in a passive rather than an active role, which hinders learning;

![]() encourages one-way communication; therefore, the lecturer must make a conscious effort to become aware of students’ problems and students’ understanding of content without verbal feedback;

encourages one-way communication; therefore, the lecturer must make a conscious effort to become aware of students’ problems and students’ understanding of content without verbal feedback;

![]() requires a considerable amount of unguided student time outside of the classroom to enable understanding and long-term retention of content. In contrast, interactive methods (discussion, problem-solving sessions) allow the instructor to influence students when they are actively working with the material;

requires a considerable amount of unguided student time outside of the classroom to enable understanding and long-term retention of content. In contrast, interactive methods (discussion, problem-solving sessions) allow the instructor to influence students when they are actively working with the material;

![]() requires the instructor to have or to learn effective writing and speaking skills.

requires the instructor to have or to learn effective writing and speaking skills.

Advantages of traditional lecture, streaming video

![]() Video streaming is available on demand – an attribute important to any self-directed instructional program.

Video streaming is available on demand – an attribute important to any self-directed instructional program.

![]() It can reach an unlimited number of participants at any given time.

It can reach an unlimited number of participants at any given time.

![]() By providing basic information to large numbers of participants via this medium, librarians can concentrate their efforts on providing in-depth and one-on-one instruction and assistance.

By providing basic information to large numbers of participants via this medium, librarians can concentrate their efforts on providing in-depth and one-on-one instruction and assistance.

![]() Today’s students are comfortable with audiovisual formats and enthralled by the Internet.

Today’s students are comfortable with audiovisual formats and enthralled by the Internet.

![]() With well-crafted content, their interest can be engaged by streamed media projects.

With well-crafted content, their interest can be engaged by streamed media projects.

Disadvantages of traditional lecture, streaming video

![]() Equipment is needed, and even basic equipment costs money. You must budget for this or find willing collaborators and supporters who can provide what is needed.

Equipment is needed, and even basic equipment costs money. You must budget for this or find willing collaborators and supporters who can provide what is needed.

![]() Careful analysis of instructional needs and thorough conceptualization of a possible project are necessary for a successful end product. If you are not comfortable with such conceptualization and planning, you should enlist help from someone who is.

Careful analysis of instructional needs and thorough conceptualization of a possible project are necessary for a successful end product. If you are not comfortable with such conceptualization and planning, you should enlist help from someone who is.

![]() Updating may be necessary. When changes occur that affect the content of your video, you must revise the product or deliver out-of-date information. Careful planning can mitigate this problem, but it is important to consider when deciding what content to deliver via streaming.

Updating may be necessary. When changes occur that affect the content of your video, you must revise the product or deliver out-of-date information. Careful planning can mitigate this problem, but it is important to consider when deciding what content to deliver via streaming.

![]() Bandwidth can be a barrier. Although products continuously improve, streaming still works best on high-speed Internet connections not often found in private homes. If you are hoping to deliver instruction to distance education students via a phone line, streaming media is not yet the optimal solution. (Cox and Pratt, 2002)

Bandwidth can be a barrier. Although products continuously improve, streaming still works best on high-speed Internet connections not often found in private homes. If you are hoping to deliver instruction to distance education students via a phone line, streaming media is not yet the optimal solution. (Cox and Pratt, 2002)

Despite the many disadvantages of the traditional lecture, it remains the most popular method of ILI in academic libraries. Librarians may not want to relinquish the control that the traditional lecture affords; however, many are facing the reality that a student-centered learning method has a greater retention level and is more effective overall at increasing students’ usage of the library and advancing cognitive skills.

Active learning instruction (AL)

Active learning has become a popular approach for ILI at academic libraries. It is much more than just a buzzword or pedagogical fad; it is a formal movement. From the earliest roots of library instruction in the United States, it was believed that the traditional lecture may not be the best way to teach students about the library (Lorenzen, 2001). Though active learning has received considerable attention recently in higher education and ILI, its use in education is not a new idea. It dates back to ancient Greece and the early teaching methods of Socrates. The Socratic Method relied on students interacting with each other and the teacher. Socrates did not lecture to his students – lecturing did not become popular until much later in history when large formal institutions of education were established (Lorenzen, 2001). In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries academic librarians introduced active learning as an instruction method and an alternative to lecturing, believing that lecturing was hindering the students’ education about the library. The recent driving force behind the active learning movement in academic libraries, and in higher education in general, was a report released by the National Institute of Education in 1984 titled Involvement in Learning: Realizing the Potential of American Higher Education. The report was an attempt to improve students’ participation in their own education and recommended that students take greater responsibility in their learning (Lorenzen, 2001). Since then the active learning approach to instruction has spread throughout higher education and attracted strong advocates within the academic library community. Librarians are incorporating active techniques into ILI traditional lectures, embracing the active learning approach, and developing a wide range of active learning ILI sessions.

Active learning stands in contrast to the traditional method of lecturing where the student is passive. The difference has been aptly compared using the metaphors of a glass jar being filled with liquid and a lamp being lit. The jar is filled by pouring liquid into the empty vessel similar to the traditional learning paradigm where an expert instructor transmits class content as the student sits passively absorbing the information. Active learning employs the latter metaphor where an instructor creates opportunities and engages students, guiding them to understand and encouraging them to apply the information during instruction. They help ‘light the lamp’ of student learning (University of Minnesota, 2008). There are four types of learning that fall into this category: active learning, cooperative learning, collaborative learning and problem-based learning (PBL). Each is distinguishable by core elements that differentiate between each method.

Active learning

This method is defined as any type of instruction that engages students in their own learning process. The core elements of this method are student activity and engagement in the learning process (Prince, 2004). This can include anything that the student does in the classroom or is involved with to enhance learning subject content other than listening to the instructor’s lecture. Students and their learning needs are the foundation for any active learning strategy. Strategies can include:

![]() writing exercises in which students react to lecture material;

writing exercises in which students react to lecture material;

![]() talking and listening exercises where the students provide feedback on what they have learned;

talking and listening exercises where the students provide feedback on what they have learned;

![]() reading exercises where the students summarize and create note checks to help process what they have read and help them develop the ability to focus on important information;

reading exercises where the students summarize and create note checks to help process what they have read and help them develop the ability to focus on important information;

![]() reflection exercises, allowing students to pause for thought, to use their new knowledge to teach each other, or to answer questions on the day’s topics – one of the simplest ways to increase retention;

reflection exercises, allowing students to pause for thought, to use their new knowledge to teach each other, or to answer questions on the day’s topics – one of the simplest ways to increase retention;

![]() complex group exercises in which pairs of students apply course material to ‘real life’ situations and/or to new problems.

complex group exercises in which pairs of students apply course material to ‘real life’ situations and/or to new problems.

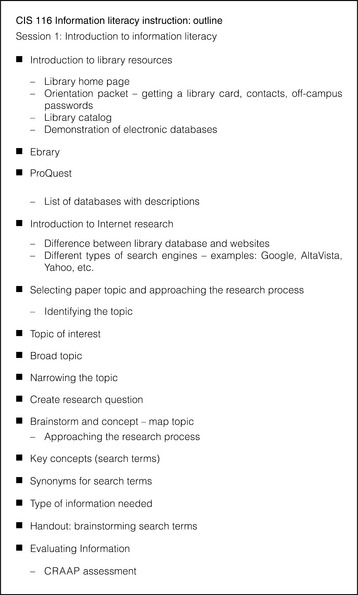

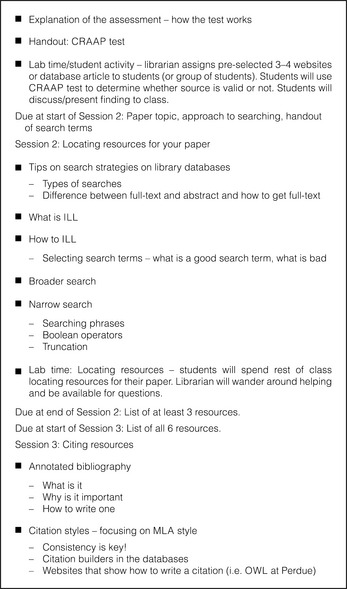

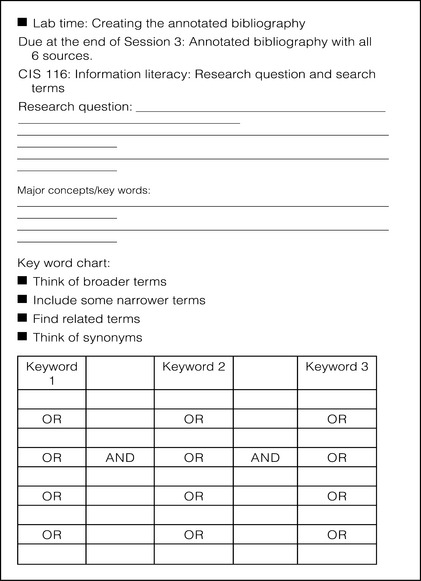

Here, the premise is learning by doing; it does not mean abandoning the traditional lecture altogether. However, instructors must take time to involve the students and give them time to work with the information being provided. Figure 1.4 provides a basic active learning session developed for a CIS 116 class at Cochise College Libraries. It includes a worksheet for students to record their research questions and key words to be used in their initial research queries.

Cooperative learning

This subset of active learning covers group activities in which students are divided into groups of three or more, rather than alone or in pairs, and are assigned complex tasks, such as multiple-step exercises or a research project using multiple databases. It can be defined as a structured form of group work where students pursue common goals while being assessed individually. The core element held in common is a focus on cooperative incentives rather than competition to promote learning (Prince, 2004). As the term ‘cooperative learning’ suggests, students working in groups will help each other to learn. It employs the concept that many heads are better than one or two.

Cooperative groups encourage discussion of problem solving techniques and expose students to different learning styles and developing social skills. Group members share the various roles and are interdependent in achieving the group learning goal. While the academic task is of primary importance, students also learn the importance of maintaining group health and harmony, and respecting individual views (Saskatoon Public Schools, 2009). A simple group assignment in an ILI session would be to ask students to acquire five resources on a given topic using the library’s online catalog and bibliographic databases, and ask the students to follow the following instructions:

1. As a group, decide who will be the Recorder, Presenter, Timer, Organizer.

2. Everyone must contribute to group discussions and the wording on the poster.

3. The Organizer gathers and returns the materials needed for the lesson.

4. The Recorder draws the chart and writes the words on the chart.

5. The Timer keeps track of the time and makes sure everyone takes turns and contributes.

6. The Presenter presents the chart for the group when asked by the teacher.

There is an ever increasing need for interdependence, not just in education but in all levels of our society. Providing students with the tools to effectively work in a collaborative environment can be beneficial in many aspects of life outside of education. Cooperative learning is one way of providing students with a well defined framework from which to learn from each other (Saskatoon Public Schools, 2009).

Collaborative learning

This subset refers to those classroom strategies that have the instructor and the students placed on an equal footing working together in, for example, designing assignments, choosing lesson content, and students presenting material to the class. The core element of collaborative learning is the emphasis on student interactions rather than on learning as a solitary activity (Prince, 2004). Students need to be willing to accept the challenge provided by collaborative-based learning. This means they must be heavily involved and expect to contribute to the learning process. They need to feel that their own experiences, interests, and judgments matter, and that they have some choice in the inquiries they design in collaboration with their teachers (Fitzpatrick, 1998).

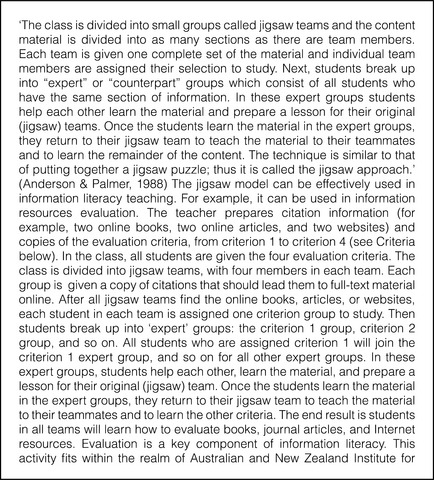

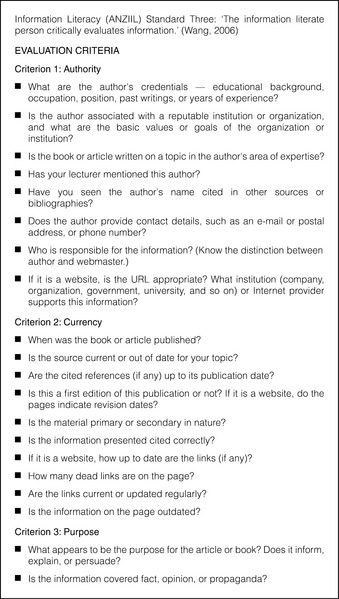

Collaborative learning, like cooperative learning, is team oriented and students learn in a community-of-learners environment, where they act as community members. Students engage in many different class activities, interacting with each other and solving problems or completing tasks together. They think and talk about their thinking, and engage in problem solving techniques. The teacher acts as a motivator and develops ways to enhance student critical thinking. In this learning environment, students’ independent and reflective thinking skills will be improved (Wang, 2006). The Learning Services Manager at the University of Auckland, Li Wang, believes collaborative learning increases students’ performance levels. She claims, ‘Through collaborative activities and interactions, teachers and librarians can provide learners with effective assistance that will enable them to perform at higher levels than they would otherwise’ (Wang, 2006). Table 1.3 compares a traditional library classroom with a collaborative learning environment. Notice that the librarian becomes a co-learner in this community learning environment, reversing roles with the student who becomes a contributor to the instruction of the class. One type of collaborative learning method is called the ‘Jigsaw Method.’ It was created in the 1970s by Eliot Aronson, an instructor at the University of Texas, to promote student learning and increase student motivation. More recently it has gained popularity in ILI at many academic libraries. Figure 1.5 contains a description of the jigsaw method and an ILI practice exercise designed by Wang. In the information literacy collaborative learning community, students and librarians are all equal community members playing different roles than the traditional ILI method and creating knowledge, not transmitting it. Implementing collaborative learning techniques enables students to actively participate in the learning process, helps librarians develop an information literacy community of learners, and helps students reach their full potential developmental level (Wang, 2006).

Table 1.3

The traditional library classroom vs. the collaborative learning environment

| Role/content/environment | Traditional library classroom | Collaborative learning environment |

| Role of student | Listener, observer, note taker, doing what librarian instructs | Problem solver, contributor, co-instructor, discussant, responsible for their own learning and instruction, co-designer of class activities |

| Role of librarian | Classroom manager, didactic teacher, authority of instruction | Knowledgeable co-learner, guide to student learning, motivator, co-designer of class activities |

| Content | Focus on library, highly instructor controlled and constructed and transmitted | Focus on information processes, focus on learning through class activities |

| Environment | Stuctured, competitive, formal knowledge transferred by librarian | Democratic, informal, knowledge created through collaboration of student and librarian |

Problem-based learning (PBL)

Problem-based learning is an active learning technique by which learning takes place through the solving of real-world problems. It was pioneered with medical students at McMaster University whose website defines PBL as ‘any learning environment where the problem drives the learning’ (Department of Chemical Engineering, 2006). Problems relevant to the subject content are introduced at the beginning of the lesson and are the motivation for learning throughout the instruction period. The approach challenges students to learn by engaging the problem and places them in an active problem solver role. There are several unique aspects that define the PBL approach:

![]() Learning takes place within the contexts of authentic tasks, issues, and problems that are aligned with real-world concerns.

Learning takes place within the contexts of authentic tasks, issues, and problems that are aligned with real-world concerns.

![]() In a PBL course, students and the instructor become colearners, coplanners, coproducers, and coevaluators as they design, implement, and continually refine their curricula.

In a PBL course, students and the instructor become colearners, coplanners, coproducers, and coevaluators as they design, implement, and continually refine their curricula.

![]() The PBL approach is grounded in solid academic research on learning and on the best practices that promote it. This approach stimulates students to take responsibility for their own learning, since there are few lectures, no structured sequence of assigned readings, and so on.

The PBL approach is grounded in solid academic research on learning and on the best practices that promote it. This approach stimulates students to take responsibility for their own learning, since there are few lectures, no structured sequence of assigned readings, and so on.

![]() PBL is unique in that it fosters collaboration among students, stresses the development of problem solving skills within the context of professional practice, promotes effective reasoning and self-directed learning, and is aimed at increasing motivation for life-long learning. (Purser, 2010)

PBL is unique in that it fosters collaboration among students, stresses the development of problem solving skills within the context of professional practice, promotes effective reasoning and self-directed learning, and is aimed at increasing motivation for life-long learning. (Purser, 2010)

PBL is gaining in popularity and can even be integrated into the one-shot library instruction periods most favored by librarians and faculty (Kenney, 2008). PBL is a group activity: students are separated into groups and given a real-world current problem to analyze. PBL is a ‘teaching strategy that takes everyday situations and creates learning opportunities from them’ (Macklin, 2001). Students start by recording the information they already have about the problem and what additional information is needed to solve the problem. Then students develop a strategy for solving the problem. The librarian can act as a guide, showing the students the types of resources they will need, and how to use and evaluate the resources. The students collect the information and develop a worksheet of the resources they found. Each group can then present the information and review their performance (Kenney, 2008). The problem topic should be relevant to the discipline of the class receiving the instruction. Kenney developed the following problem for an ILI session she planned to give a Speech Communications class.

You are the senior advisor to Senator Brittany Aguilera from New York City. In one hour she needs to give a two-minute presentation on the Children’s Internet Protection Act (CIPA) to her constituents, but she doesn’t know if she’s in favor of it or against it. Your job is to find reliable, authoritative information from at least five different sources. The Senator is up for reelection and your job depends upon your getting accurate information fast.

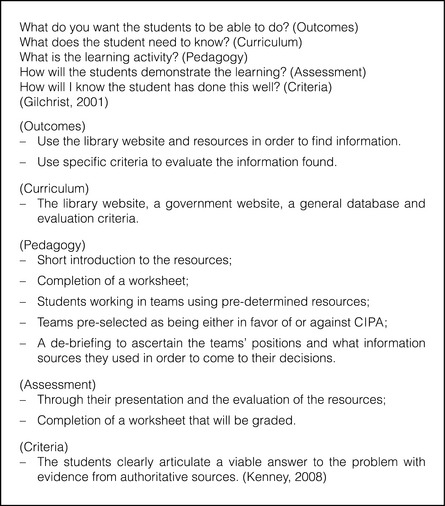

In a presentation at the ACRL’s Immersion Program, Deb Gilchrist presented a list of questions that can be used to develop a lesson plan for solving problems in a PBL instructional period. Figure 1.6 shows instructional goals developed by Kenney for solving the problem she presented to the Speech Communications class.

Advocates of the use of active learning in ILI claim it is more effective than traditional instruction at everything from encouraging library usage to increasing student retention rates. The method offers many advantages and benefits; however, there are some disadvantages to using an active learning technique.

Active learning advantages

1. may increase critical thinking skills in students;

2. enables students to show initiative;

3. involves students by stimulating them to talk more;

4. incorporates more student input and ideas;

5. easier to assess student learning;

6. better meets the needs of students with varying learning styles.

Active learning disadvantages

1. librarian may need to become expert in many content areas;

2. may be difficult to organize active learning experiences;

3. requires more time and energy and may be stressful for librarian;

4. librarian may receive less favorable evaluations from students;

5. students may be stressed because of the necessity to adapt to new ways of learning;

There is a foundational shift occurring within higher education from teaching to learning and from inputs to learning outcomes. This shift is driving the popularity of active learning techniques, and research is supporting the claims that it is more effective and beneficial to student learning. It engages the students and transfers responsibility from the teacher to the student. Active learning offers a useful alternative to traditional instruction and many librarians are riding the active learning wave that is rolling through all levels of education.

Computer assisted instruction (CAI)

Computer assisted instruction (CAI) refers to any instruction presented on a computer. Most ILI CAI is delivered through web-based tutorials. The web-based tutorial (WBT) is an attractive method for delivery of ILI and has become ubiquitous in academic libraries. WBT is an innovative approach in which CAI is transformed by Internet technologies. It allows participants to engage in self-directed, self-paced learning in almost any topic. Tutorials should not be a collection of information pages full of text and descriptions. Instead, they should be an interactive tool with different activities that engage the student in active learning with feedback and quizzes. A tutorial usually includes numerous modules with a variety of subjects to walk the student into becoming information literate. The subjects can include:

| Information literacy | Library services |

| Searching in information | Evaluation of Internet |

| sources | information |

| Location of books or | Plagiarism and |

| articles | copyright |

| Databases | Library services and |

| Thematic resources | resources |

| Search strategies | Citation |

| Catalog searching | Browsers |

| Academic journals | Plagiarism and citation |

| Internet |

Figure 1.7 is a list of subject modules developed by the librarians at the State University of New York at Oswego.

To be effective these tutorials should be learning modules that promote the institutional needs of the library and relate the information library skills the library wishes its participants to achieve (Tobin and Kesselman, 1999). There are two important points to keep in mind when creating a web-based tutorial. First, find out exactly what it is your audience needs to learn and teach them that. Next, keep it simple and basic. When discussing the principles of designing web-based instruction the textbook Information Literacy Instruction (2001) refers to this quote by library web designer Mark Stover: ‘If content is clearly king, then need is surely emperor’ (Stover and Zink, 1996). Grassian and Kaplowitz state, ‘Simply designed web based materials may take great time and effort to create, yet they can make an enormous difference in insuring that significant learning takes place’ (Grassian and Kaplowitz, 2001). Grassian and Kaplowitz assert the basic steps in planning instruction are always the same:

1. RECOGNIZE the participant need

2. DESCRIBE AND ANALYZE the present institutional situation and available resources

3. DEVELOP instructional goals and objectives

4. DESIGN appropriate method and materials

6. EVALUATE AND REVISE (Grassian and Kaplowitz, 2001)

Any web editing software can be used to create the tutorials, though many libraries use animation created with Flash software, video, and other graphics which can present many interactivity possibilities and add interesting visuals to the tutorials.

The spread and popularity of distance education has driven librarians to embrace CAI. While many librarians are excited about the great potential and advantages of using this medium, there are disadvantages and warnings against using CAI just for the sake of using a new technology. CAI has a number of advantages; first and foremost, it can save time that is being devoted to repetitive instruction by delivering asynchronous instruction available anytime, anywhere to participants for first time use or a review (Kaplowitz and Grassian, 2009). Another important valued benefit is that it actively involves the student in the learning process. It is impossible for the student to be a totally passive member of the situation, and this very activity and involvement facilitate learning (Chambers and Sprecher, 1980). It also allows the students to learn at their own pace. Furthermore, CAI provides immediate and systematic feedback that supports more effective student learning. The main drawback to using CAI is the fact that not all students have access to the Internet and knowledge of Internet technologies to use the tutorials. Though this is becoming less of a problem there still remains a digital divide in participant access and knowledge.

Recent research has shown that CAI in academic libraries is still at an early stage of development and though most tutorials follow sound pedagogical strategies for instruction, there is much room for improvement (Somoza-Fernández and Abadal, 2009). Areas most in need of improvement include defining learning objective and outcomes more clearly and giving more attention to the concepts behind the mechanics of CAI. Other suggestions include increasing interactivity: ‘The exercises should incorporate more elements of feedback because the existing ones are too simple. More game-type exercises should be included to complement the questionnaire-type exercise’ (Somoza-Fernández and Abadal, 2009). The tutorials should also offer different levels of difficulty, such as a basic and an advanced level. Finally, CAI should develop more instructional methods to accommodate distance-learning students, and the tutorials should develop elements that enhance usability and accessibility to allow greater interactivity of the students with the system (Somoza-Fernández and Abadal, 2009). CAI is the future of ILI and will someday overtake traditional instruction as the favored method of delivery by all academic libraries. Librarians are still just learning how to achieve the full benefits of this learning tool.

Learner-centered instruction (LCI)

In learner-centered instruction (LCI), learners are partners in their own learning and they learn from one another as well as from the instructor. Student involvement is the foundational element of LCI and as in active learning the student is encouraged to participate in the learning process. However, in LCI the students are not just active participants in learning, they are also active participants in instructing and teaching. Grassian and Kaplowitz claim that the LCI approach rests on three principles, collaboration, participation and responsibility (Grassian and Kaplowitz, 2009). There is sharp contrast between LCI and teacher-centered instruction. Teacher-centered instruction is considered the banking approach to teaching by which the teacher deposits the information into the empty account of the student, metaphorically giving the student a fish. LCI teaches the student to fish and the students take on a larger role in the learning process, actually teaching themselves as they learn. Table 1.4 presents the differences between a teacher-centered classroom and a learner-centered environment. It defines the principles mentioned by Grassian and Kaplowitz, as students collaborate with other students and the instructor by taking on more instructional and learning responsibility through their participation. The center of power and authority of the teacher-centered classroom is diffused, with students seeking out knowledge rather than knowledge primarily coming from the teacher.

Table 1.4

Teacher-centered vs. learner-centered instruction

| Teacher-centered | Learner-centered |

| Focus is on instructor | Focus is on both students and instructor |

| Focus is on language forms and structures (what the instructor knows about the language) | Focus is on language use in typical situations (how students will use the language) |

| Instructor talks; students listen | Instructor models; students interact with instructor and one another |

| Students work alone | Students work in pairs, in groups, or alone, depending on the purpose of the activity |

| Instructor monitors and corrects every student utterance | Students talk without constant instructor monitoring; instructor provides feedback/correction when questions arise |

| Instructor answers students’ questions about language | Students answer each other’s questions, using instructor as an information resource |

| Instructor chooses topics | Students have some choice of topics |

| Instructor evaluates student learning | Students evaluate their own learning; instructor also evaluates |

| Classroom is quiet | Classroom is often noisy and busy |

Source: http://www.nclrc.org/essentials/goalsmethods/learncentpop.html

The idea behind LCI is to empower students in the learning process and cultivate life-long learning skills. Instead of instruction being delivered in the form of information-laden lectures, lessons are designed to engage students in learning experiences that enable them to learn content and ‘learn how to learn’ at the same time (Cuseo, 2006). The students are not passive learners, sitting in a classroom listening to the instructor. They are engaged learners participating as active agents in the learning process. The instructor’s role also changes from a ‘knowledge-laden professor’ to a class facilitator, coaching the students while they instruct themselves. The ‘sage on the stage’ becomes the ‘guide by the side’ (Cuseo, 2006).

One of the major limitations attached to library instruction is the problem of connectedness. The students are confronted with a new teacher and with content that they realize will not be graded or assessed. Consequently the students do not feel connected to the instructor or the material and they do not talk or engage with each other. An LCI approach is a possible solution to this connectedness problem. Michael Lorenzen, an academic librarian at Central Michigan University, designed an LCI lesson plan for use in a 90-minute library instructional period. He claims this technique was successful at overcoming the connectedness limitation. He used an LCI technique called a jigsaw. In a jigsaw activity, instructional content is broken into several small parts and the class is divided into several small groups. Each part is assigned to a group; the groups analyze the material, working among themselves to develop a presentation about the material. The groups then reform as a class and present what they have learned about their part. As the groups are teaching the class about their content, the instructor acts as a facilitator, adding expertise to the process and filling in any relevant points the groups may have missed. Figure 1.8 has a description of the lesson plan Lorenzen used.

Figure 1.8 Jigsaw activity for LCI Source: Lorenzen (2004)

LCI has many advantages. For example, students obtain information and direction from themselves and do not rely on gaining these from the teacher. It helps the student develop leadership skills and become familiar with the role of information provider instead of passive learner. Additional benefits to both student and teacher are that students learn to problem solve by themselves, and the teacher is exposed to new learning experiences and lessons. There are also disadvantages. For example, the open-ended lesson plans of LCI may not give enough direction for students to obtain the intended knowledge and skills. Also, students often need encouragement to stay on task and may lack the initiative and motivation to get all the required work done to disseminate the information to the whole class. Finally, students need teachers to be more than a facilitator; the teacher has to command accountability so that students learn to listen to the teacher when necessary. LCI requires a balance between teacher-centered and participant-centered instruction and an effective LCI lesson plan incorporates elements of both (ELED Blog, 2006).

Self-directed, independent learning (SDIL)

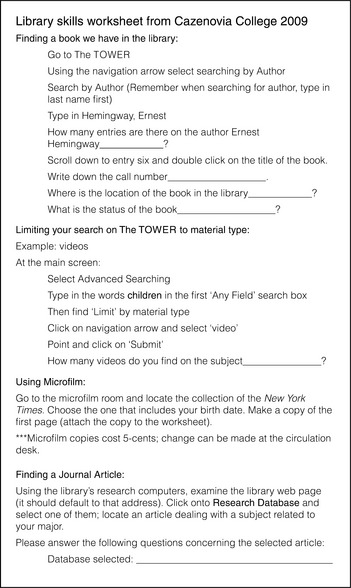

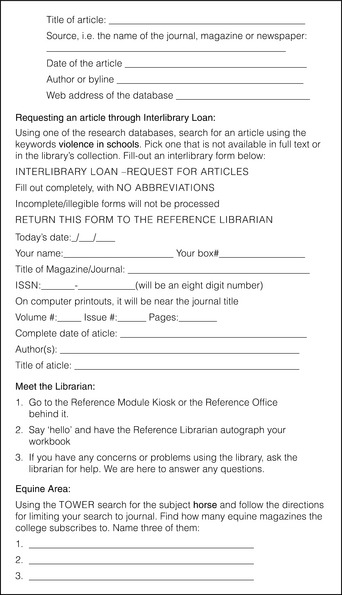

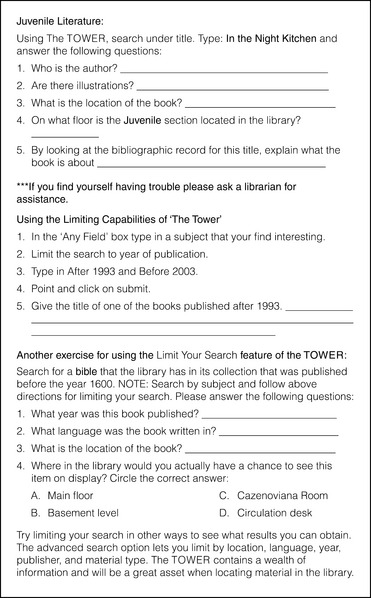

In SDIL students take the primary responsibility for their own education. They take the initiative of what occurs, and select, manage, and assess their own learning activities. The activities can be pursued at any time, in any place, by any means, asynchronously or synchronously. The activities can be delivered through handouts, workbooks, both physical hard copies and web-based tutorials. A basic library skills worksheet is depicted in Figure 1.9. Materials and content are provided to the students and they complete the lessons at their own pace. Self-directed learning requires a commitment from the student. Grassian and Kaplowitz claim that being a self-directed learner is a characteristic of the learner, not the methodology or instruction (Grassian and Kaplowitz, 2009). The self-directed learner goes beyond the material presented in the worksheets, exploring other resources to expand on the learning experience, and looks for supplemental material to help them understand the lessons.

Figure 1.9 Library skills worksheet Source: Casenovia College (2009) http://www.cazenovia.edu/default.aspx?tabid=705

Supporters of SDIL claim it is the most effective method for actively engaging the student in the learning process. They believe SDIL personalizes the learning experience and motivates the students to discover things by themselves. There are many advantages and disadvantages when using the self-directed method.

Advantages of SDIL

Disadvantages of SDIL

![]() requires strong commitment from learner;

requires strong commitment from learner;

![]() many not used to being self-directed learners;

many not used to being self-directed learners;

![]() lack of feedback from instructor;

lack of feedback from instructor;

![]() lesson content may not contain information needed by learner to understand subject;

lesson content may not contain information needed by learner to understand subject;

The popularity and convenience of web-based instruction demand that librarians develop new ways for students to learn independently. Though face-to-face one-shots are still the standard for ILI, the future is web-based instruction and students will insist that the instruction be available asynchronously so that they can take advantage of it whenever and wherever they want.

Take-home message

This chapter described what ILI is and what it has become. Though the concept has evolved over the years from teaching students to be information literate to an outreach marketing approach, librarians still have the original goal driving their ambitions, to teach participants how to find, evaluate and use information effectively. The chapter also introduced the various methods of instruction that are available. The traditional method continues to be the most popular with academic librarians because of its convenience and the time constraints involved in prioritizing instructional time within class periods. Active learning methods have been used in web-based tutorials from the beginning, and academic librarians are also experimenting with the active learning methods in face-to-face sessions. This will gain popularity as the shift in learning paradigms spreads throughout higher education. Many traditional lecture sessions already employ more than one method in their delivery. The future of ILI is in computer-assisted instruction and as distance learning is used in a greater percentage of the classes offered, CAI will become the standard. Knowing what methods are available is just the first step when deciding on which method would best work for your institution and situation. There are many other elements in the equation for selecting an effective method, and the next chapter presents one of the most significant. Defining the objectives of your ILI program will most likely narrow your choice and answer many questions in determining which method will be most effective for your participants.

References

American Library Association Presidential Committee on Information Literacy. Final Report. Chicago, IL: American Library Association; 1989.

Anderson, F., Palmer, J., The Jigsaw Approach: Students Motivating Students. Education 109. 1988. [no. 1(59)].

Ardis, S. Instruction: Teaching or Marketing? Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship. Available at http://www.istl.org/05-spring/viewpoints.html, 2005.

Bennett, B., Dacio, H., Logan, T., Rousseau-Smith, M., Strathman, K., Video Instruction Versus Traditional Lecture: Recalling Simple Steps. Master Thesis. Californina State University, 2009. San Bernardino available at. http://emurillo.org/Classes/Class2/documents/VideoInstruction.doc

Bruce, C.S. Seven Faces of Information Literacy. Adelaide: Auslib Press; 1997.

Campbell, S., Defining Information Literacy in the 21st Century August 22–27. Paper presented at the World Library and Information Congress. 70th IFLA General Conference and Council, Buenos Aires, 2004. available at. www.ifla.org/IV/ifla70/papers/059e-Campbell.pdf

Casenovia College. Library Skills Worksheet. Available at http://www.cazenovia.edu/default.aspx?tabid=705, 2009.

Chambers, J., Sprecher, J. Computer Assisted Instruction: Current Trends and Critical Issues. Available at http://www.csuvc.com/drupal/files/ed1.pdf, 1980.

Crowther, K., Wallace, A. Delivering Video-Streamed Library Orientation on the Web. College & Research Libraries News. 2001; 62(3):280–285.

Cox, C., Pratt, S. The Case of the Missing Students and How We Reached Them Through Streaming Video. Computers in Libraries. 2002; 22(3):40–45.

Cuseo, J., The Case for Learner-Centered Education. On Course Workshop, Student Success Strategies. 2006 Available at. http://www.oncourseworkshop.com/Miscellaneous018.htm

Department of Chemical Engineering. Problem-based learning especially in the context of large classes. Available at www.chemeng.mcmaster.ca/pbl/pbl.htm, 2006.

Dewey, M. The Profession. American Library Journal. 1876; 1(September):5–6.

Doyle, C., Outcome Measures for Information Literacy within the National Education Goals of 1990: Final Report of the National Forum on Information Literacy. Summary of Findings. US Department of Education, Washington, DC, 1992. (ERIC document no; ED 351033). Available at. http://eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2/content_storage_01/0000000b/80/23/4a/12.pdf

ELED, 3110 Blog. 2006. Available at. http://eled3110asturgill.blogspot.com/2006/08/most-of-us-are-very-familiar-with.html

Fitzpatrick, C. Information Literacy and Learning. Available at http://www.edu.pe.ca/bil/bil.asp?ch1.s4.gdtx, 1998.

Fosmire, M., Macklin, A. Riding the Active Learning Wave: Problem-Based Learning as a Catalyst for Creating Faculty–Librarian Instructional Partnerships. Available at http://www.istl.org/02-spring/article2.html, 2002.

Gilchrist, D., Institute for Information Literacy Immersion Program. 2001.

Grassian, E., Kaplowitz, J. Information Literacy Instruction: Theory and Practice, second edition. New York, NY: Neal-Schuman; 2001.

Grassian, E., Kaplowitz, J. Information Literacy Instruction: Theory and Practice, third edition. New York, NY: Neal-Schuman; 2009.

Hardesty, L.L., Scmitt, J.P., Tucker, J.M. Participant Instruction in Academic Libraries: A Century of Selected Readings. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press; 1986.

Kenney, B. Revitalizing the One-Shot Instruction Session Using Problem-Based Learning. Available at http://docs.rwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1012&context=librarypub, 2008.

Koufogiannakis, D., Effective methods for teaching information literacy skills to undergraduate students. A systematic review and meta analysis. 2006 Accessed 5 September 2009 at. http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/EBLIP/article/viewArticle/76

Kuhlthau, C.C. Seeking Meaning: A Process Approach to Library and Information Services. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation; 1993.

Lorenzen, M., Brief History of Library Instruction in the United States of America. Illinois Libraries. 2001 Available at. http://www.libraryinstruction.com/lihistory.html

Lorenzen, M. Active Learning and Library Instruction. Available at http://www.libraryinstruction.com/active.html, 2001.

Lorenzen, M. Encouraging Community in Library Instruction: A Jigsaw Experiment in a University Library Skills Classroom. Available at http://www.libraryinstruction.com/jigsaw.html, 2004.

Macklin, A. Integrating Information Literacy Using Problem-Based Learning. Reference Services Review. 2001; 29(4):307.

National Institute of Education. Involvement in Learning: Realizing the Potential of American Higher Education. Available at http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/32/05/78.pdf, 1984.

Owusu-Ansah, E.K. Information Literacy and the Academic Library: A Critical Look at a Concept and the Controversies Surrounding It. Journal of Academic Librarianship. 2003; 29:219–230.

Owusu-Ansah, E.K. Debating Definitions of Information Literacy: Enough is Enough. Library Review. 2005; 54(6):366–374.

Prince, M. Does Active Learning Work? A Review of Research. Available at http://www4.ncsu.edu/unity/lockers/participants/f/felder/public/Papers/Prince_AL.pdf, 2004.

Purser, R., Center for Creative Inquiry. Teaching Philosophy. 2010 Available at. http://online.sfsu.edu/~rpurser/revised/pages/problem.htm

Schools, Saskatoon Public. Instructional Strategies Online. Available at http://olc.spsd.sk.ca/de/pd/instr/strats/coop/index.html, 2009.

Somoza-Fernández, M., Abadal, E. Analysis of Web Based Tutorials Created by Academic Libraries. The Journal of Academic Librarianship. 2009; 35(2):126–131.

Staines, G., Web-Based Course Task Force. The SUNY Council of Library Directors. 1998 Final Report. Available at. http://www.sunyconnect.suny.edu/ili/scld.htm

Stover, M., Zink, S.D. World Wide Web Home Page Design: Patterns and Anomalies of Higher Education Library Home Pages. Reference Service Review. 1996; 24(3):7–20.

Teacher vs. Learner-Centered Instruction. Available at http://www.nclrc.org/essentials/goalsmethods/learncentpop.html.

Tobin, T., Kesselman, M. Evaluation of Web-Based Library Instructional Programs. Available at http://archive.ifla.org/IV/ifla65/papers/102-163e.htm, 1999.

University of Minnesota, What is Active Learning. Center for Teaching and Learning. 2008 Available at. http://www1.umn.edu/ohr/teachlearn/tutorials/active/what/index.html

University of Wisconsin, Madison, Center for the Integration of Research, Teaching and Learning. Advantages and Disadvantages of the Traditional Lecture Method. 2006 Available at. http://cirtl.wceruw.org/diversityresources/resources/resource-book/advantagesanddisadvantagesofthetraditionallecturemethod.htm

Wang, L. Sociocutural Lear’ning Theories and Information Literacy Teaching Activities in Higher Education. Available at http://vnweb.hwwilsonweb.com/hww/results/external_link_maincontentframe.jhtml;hwwilsonid=DHWR3NYRPSAUFQA3DIKSFGGADUNGIIV0, 2006.

Weisskirch, R.S., Silveria, J.B. The Effectiveness of Project Specific Information Competence Instruction. Research Strategies. 2007; 20:370–378.