Objectives of instruction

Abstract:

This chapter identifies the measures of success when determining the effectiveness of ILI. Cognitive outcomes, measuring changes in knowledge, are considered a standard by many ILI programs; however, these are only one aspect of determining effectiveness. This chapter describes different cognitive outcomes as well as behavioral outcomes which measure changes in actions, and affective outcomes that measure changes in attitudes and values. The behavioral outcomes address increases in student library usage and information seeking behavior of participants. The cognitive outcomes include increased learning skills and library skills. The affective outcomes involve decreasing library anxiety and increasing student self-efficacy.

The role of assessment

In the twenty-first century, assessment has become an integral part of higher education and one of the driving forces behind this movement is accountability (Radcliff et al., 2007). In the 1970s, several changes in higher education brought about the cry for accountability. Many universities faced a financial crisis, the population of students attending college became more diverse, and concerns were raised that college graduates did not have the skills and abilities needed in the workplace. The value of higher education came to be questioned by the public and politicians (Northern Illinois University, 2010). Four reports were issued in the 1980s, The Access to Quality Undergraduate Education, Integrity in the College Curriculum, Involvement in Learning, and To Reclaim a Legacy, that brought accountability to the forefront in higher education. The results of these reports produced specialized accreditation bodies and a demand for an outcomes approach to evaluation in higher education instruction. What began as an external influence on education has grown into an internal force: improvement as accountability (Northern Illinois University, 2010).

As the accountability movement progressed, information literacy became a general educational requirement at public institutions in higher education. The six regional accreditation organizations of higher education and several professional and disciplinary accrediting organizations have included information literacy in their standards, either implicitly or explicitly (Saunders, 2007). The academic library has always been the leader in promoting information literacy within higher education, and the decision to make it an educational requirement obligated academic libraries to address how they would measure success within their instructional programs. The Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) have developed a set of competency standards for information literacy in higher education (see Appendix) to evaluate the information literate student. Many libraries that use cognitive outcomes to determine effectiveness use the standards to measure the success of their programs. Connecting success with learning outcomes was a logical choice for academic libraries because it associated the library with institutional instructional goals and attached the library to the instructional process. Many libraries use cognitive outcomes to determine effectiveness, and with the evolution of ILI to become a marketing tool the measures of other options were explored to determine instructional effectiveness. Other measures of effectiveness use the measures defined by the specialized accreditation organizations that evaluate the academic standards. For example, the Handbook for Accreditation of the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools (NCA) includes a criterion that demands organizations learning resources from the library support student learning and that it is critical for colleges to assess actual student use of the resources (NCA, 2003). Using these measures, a library could determine effectiveness by measuring students’ increased usage of the library after receiving library instruction. Whatever measure an academic library chooses to use, institutional assessment has to be considered before any decision is made.

Measuring effectiveness of instruction

When selecting an effective method of ILI for a specific situation, first one must define what will determine the success of the ILI program. A program needs to determine what the instructional goals will be to assess the effectiveness of teaching methods. When developing an ILI program, assessment of effectiveness should be one of the earliest considerations and should be ‘built into the planning process from the very beginning’ (Grassian and Kaplowitz, 2009). There are many aspects that determine success and most can be classified into three categories: changes in cognitive outcomes, changes in behavioral outcomes and changes in affective outcomes. Changes in cognitive outcomes can be as small as remembering facts to applying what was taught to a new situation and may require more than a simple survey to collect results. Behavioral changes most often involve students increasing their usage of the library and participant information seeking behaviors. The changes can usually be measured through self-administered surveys. Affective changes including decreases in library anxiety require long survey questionnaires and a comparison of test results against a Library Anxiety Scale (LAS). Choosing the instructional goal is a major factor in the equation for selecting an effective method for a particular environment.

Behavioral outcomes

Behavioral outcomes are changes in action (e.g., improved and increased use of online library resources; improved and increased use of librarians; improved and increased use of the physical library itself). ILI programs are the most common outreach used by academic libraries today, and most often the outreach instructional goals are to get the student to use the library and its resources. Library usage is essential to the academic library maintaining a physical presence on college campuses and should be considered a primary objective in promoting the library and its resources. The Cochise College Library director, Pat Hotchkiss, believes the primary objective of most ILI is to promote use of the library and its resources. She claims, ‘It’s all about getting the students to start using our databases and coming in the door.’ Student usage also drives the expenditures on resources (Hotchkiss, 2007, 2009). Academic libraries allocate their budget using a formula of student usage, educational priorities, and materials cost (Trombley, 2003). ‘Facing yearly budgetary constraints, accountability has become essential to academic libraries’ success in today’s competitive environment’ (Trombley, 2003). Any consistent decrease in student usage will result in a reduction of the library budget. Comparatively, increased student usage statistics are sufficient justification for additional funds (Trombley, 2003; Hotchkiss, 2007). In the late 1990s two prominent researchers performed a longitudinal study to explain the use of library facilities at that time. The study, published in a 2001 issue of Library Trends, showed ‘one’s familiarity with the library had the greatest impact on library use’ (Simmonds, 2001: 630). Instruction has become the most popular method to advance student familiarity with library resources.

Library usage is a fundamental variable in determining many aspects of an academic library: it regulates hours of operation, budgetary decisions are based on increases and decreases of usage, and it controls resource acquisition and weeding. The importance of student usage to the infrastructure of the academic library makes usage an appropriate and important measurement of effective instruction. Increasing usage pertains to any resource offered by the library from online databases to the most valuable resource in the library, the librarians. Although researchers have expressed a need for more research measuring the effects of ILI on increasing usage, studies on this topic are scarce. The two studies that have been done measured the increases using self-administered surveys by participants. The survey in Figure 2.1 was used in a recent study that measured the effectiveness of ILI in increasing students’ usage of the library.

Another behavioral outcome is a change in participant information-seeking behavior. Information-seeking behavior has been of interest to librarians and information science professionals for decades. Although a large number of studies have been done on this subject, the process itself is still largely a mystery and requires more quantitative research.

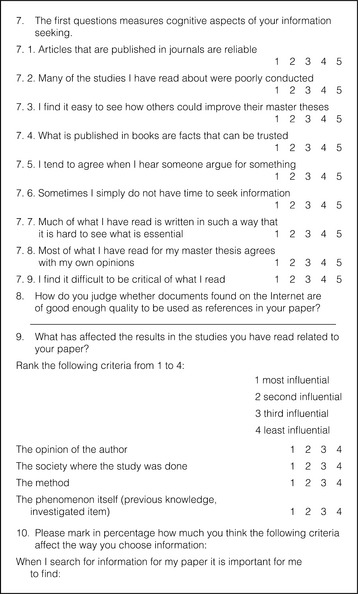

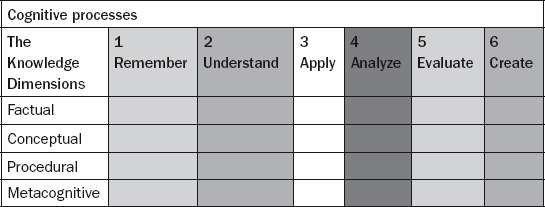

The first model for study of information-seeking behavior was developed by James Krikelas in 1983. This model suggested that the steps of information seeking were as follows: (1) perceiving a need, (2) the search itself, (3) finding the information, and (4) using the information, which results in either satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Krikelas stated that ‘information seeking begins when someone perceives that the current state of knowledge is less than that needed to deal with some issue (or problem). The process ends when that perception no longer exists’ (Krikelas, 1983). Other models have followed, and included feelings of the searcher, motivation of the participant, cognitive issues, and task definition. Components of the information-seeking process are the need for information, choice of what is relevant information, and the actual information seeking (Algon, 1997). Information-seeking behavior is much more; it consists of the use of information, which includes the absorbing, conceptualizing, manipulating, expressing, and organizing of information (Limberg, 1997). Librarians have long been puzzled by the fact that students seem to be incapable of thinking critically about information needs and through instruction have tried to improve students’ information-seeking behavior. Determining changes in information-seeking behavior is not as simple as determining the changes in usage of library resources. Measuring the changes requires extensive and complex questionnaires similar to the example in Figure 2.2.

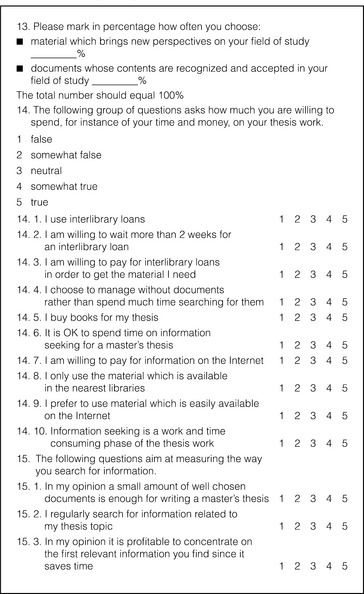

Library usage as an effectiveness standard for ILI is perhaps the most logical measurement especially in assessing the one-shot instructional periods. This can be done using a pretest/posttest research design (see Table 2.1). The data can be collected quantitatively or qualitatively. Qualitative collection can be done through interviewing and focus groups. However, this will require a much more significant time commitment and the level of assessment is still programmatic and similar to the results received through surveys. Most institutions require a quantification of the data, they want numbers and statistics, and the qualitative data must be transfigured. Also, the access to the participants will require a greater level of effort than self-administered surveys. Self-administered surveys are most convenient for academic students and can produce accurate measurements.

At the beginning of a semester the pretest surveys (example in Figure 2.1) can be administered to two groups, an experimental group that will receive the instruction and a control group that will receive no instruction. After the experimental group receives instruction, ideally, both groups would be assigned a class project that requires research. Then the experimental group would receive the ILI and the control group would not. An appropriate period of time for research should pass before the posttest surveys are administered to both groups. The pretest surveys must be organized by participants in the posttest survey so the results can be recorded correctly. When the surveys are completed the results can be input to a statistical spreadsheet or data form. By using statistical testing (?-test and analysis of variance, ANOVA) the changes in the gainscores from the pretest to the posttest results will provide a quantitative measurement for analysis. Using the surveys shown in Figure 2.1 will measure a student’s physical and virtual library usage and also determine how often they have used other Internet resources. Information-seeking behavior can be measured using the same research design as the questionnaire in Figure 2.2. This type of survey demands more commitment from the student and may require other extrinsic rewards to influence participation. The statistical testing requirements include a £-test, a factor analysis, a Pearson Regression, and a stepwise regression to determine the changes from pretest to posttest (Hiensrtom, 2002). The instrumentation and testing are more complex and the research study is more time intensive for determining information-seeking behavioral changes. However, it is certainly worth the extra work if this is the effectiveness standard of the program. Other than increasing usage, the most basic goal of library instruction is to influence students’ information-seeking skills, and scientific research is the most effective assessment of both these behavioral outcomes.

Behavioral outcomes are an excellent method for measuring the effectiveness of an ILI program. There are countless studies linking library usage with academic achievement and the results confirm that students who use the library have higher reading and academic scores. Usage statistics justify a library’s existence and are what directors use for budget justification. An ILI program that scientifically proves that it increases usage of the library or is capable of improving a student’s information-seeking skills needs no other determining factor for success.

Cognitive outcomes

In the mid-1980s, as the concept of information literacy began to develop, the assessment movement began emerging. It was no surprise that these two movements crossed paths, as accountability became an increasing concern on college campuses (NPEC, 2005). The assessment movement has grown, and assessing student learning has become a priority focus in higher education. The expansion of ILI in academic libraries has paralleled the growth of assessment, and if academic libraries want to remain relevant on university campuses they must show how they are contributing to the process of improving student learning. The most influential way they have done this is through using cognitive outcomes as an effectiveness standard for ILI.

Cognitive outcomes are changes in knowledge of participants and deal with information-processing habits. They relate to how people observe, think, problem solve and remember, and describe how people perceive, organize, and retain information (Grassian and Kaplowitz, 2009). They show what students have learned from the instruction, and the cognitive skills related to ILI include identifying necessary information, extracting the required information, evaluating information critically, and using information from a wide range of resources. The Association of College and Research Libraries has developed a set of competencies for higher education that were subsequently endorsed by the American Association for Higher Education. The five basic competencies for information literacy as they appear in ACRL’s publication, Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education (2000), are listed below:

![]() The information literate student determines the nature and extent of the information needed.

The information literate student determines the nature and extent of the information needed.

![]() The information literate student accesses needed information effectively and efficiently.

The information literate student accesses needed information effectively and efficiently.

![]() The information literate student evaluates information and its sources critically and incorporates selected information into his or her knowledge base and value system.

The information literate student evaluates information and its sources critically and incorporates selected information into his or her knowledge base and value system.

![]() The information literate student, individually or as a member of a group, uses information effectively to accomplish a specific purpose.

The information literate student, individually or as a member of a group, uses information effectively to accomplish a specific purpose.

![]() The information literate student understands many of the economic, legal, and social issues surrounding the use of information, and accesses and uses information ethically and legally. (ACRL, 2000)

The information literate student understands many of the economic, legal, and social issues surrounding the use of information, and accesses and uses information ethically and legally. (ACRL, 2000)

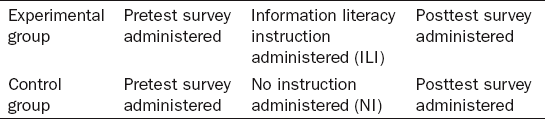

Changes in cognitive outcomes can be as small as remembering the high points of what was taught to applying what was taught to a real life situation and may require more than a simple survey to collect results. Many academic libraries assess their ILI programs by applying Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives (as revised by Anderson and Krathwohl) to determine the level of cognitive learning outcomes listed in the ACRL competencies.

Table 2.2 shows the revised Bloom taxonomy created by Anderson and Krathwohl. The revised taxonomy is more suited to determining the level of cognitive learning outcomes than the original because the new updates incorporate new knowledge into the taxonomy framework.

As indicated in Figure 2.3, the visual layout of the levels shows a conversion from the original noun levels to the verb levels of the revised structure. This transformation from noun to verb use allows the levels to be laid out with the levels of knowledge, making it easy to match activities and objectives to the types of knowledge for assessment purposes.

Figure 2.3 Levels of cognitive learning Source: Anderson and Krathwohl (2001).

Table 2.3 illustrates a cross-impact grid matching the cognitive processes with types of knowledge and includes a definition of the knowledge dimensions.

Information literacy skills can be applied to the different levels of learning in Bloom’s taxonomy. Two scholars from the University of Worcester, Massachusetts, Dr Judith Keene

Factual knowledge is knowledge that is basic to specific disciplines. This dimension refers to essential facts, terminology, details, or elements students must know or be familiar with in order to understand a discipline or solve a problem in it.

Conceptual knowledge is knowledge of classifications, principles, generalizations, theories, models, or structures pertinent to a particular disciplinary area.

Procedural knowledge refers to information or knowledge that helps students to do something specific to a discipline, subject, area of study. It also refers to methods of inquiry, very specific or finite skills, algorithms, techniques, and particular methodologies. Metacognitive knowledge is the awareness of one’s own cognition and particular cognitive processes. It is strategic or reflective knowledge about how to go about solving problems, cognitive tasks, to include contextual and conditional knowledge and knowledge of self.

and John Colvin, have designed a model of information literacy that maps the activities that students undertake while learning information literacy skills. The model maps the activities against the cognitive skill levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. Each stage of information literacy is matched up with the cognitive skills required to learn the IL skill. Table 2.4 uses the structure of the Colvin-Keene (CK) Model to define the cognitive skills employed in each of the four stages of information literacy. Colvin and Keene use the original Bloom taxonomy terms, and Table 2.4 substitutes the revised verb terms defined by Anderson and Krathwohl.

Table 2.4

Information literacy and cognitive skills

| Stages of information literacy | Bloom’s revised cognitive skills |

| Information needs identification | Remember (Knowledge, original |

| stage (ACRL Competency 1) | Bloom skills) Understand (comprehension) Apply (application) Analyze (analysis) |

| Information location and | Remember (knowledge) |

| evaluation (ACRL Competency 2) | Understand (comprehension) Apply (application) |

| Information review (ACRL Competency 3) | Remember (knowledge) Understand (comprehension) Analyze (analysis) Evaluate (evaluation) |

| Problem solution (ACRL Competency 4 and 5) | Remember (knowledge) Apply (application) Evaluate (evaluation) Create (synthesis) |

Source: Keene, Colvin and Sissons (2010)

The first stage identifies the information need and requires the student to employ different cognitive skills to advance to the next stage or competency in the cycle. A student must analyze an introduced problem, for example a class assignment requiring a research paper, and remember, understand, and apply possessed information to identify the information need. The next stage of access and evaluation of information also requires multiple cognitive skills to proceed. A student must remember, understand, and apply previous knowledge to locate, evaluate, and retrieve appropriate resources to fulfill the information need identified in stage one. In stage three the student critically analyzes the found resources and identifies the relevant information that can be used to solve the problem, summarizing pertinent facts for use. Stage four also employs multiple skills as the student synthesizes the information to solve the problem using citations and writing styles. In comparison to the presentation of the linear design ACRL Competencies, the CK Model presents information literacy as a cycle (Keene, Colvin, and Sissons, 2010). Both designs emphasize always improving information literacy skills, but the CK Model defines the information literacy process that a student goes through while completing a research assignment (see Figure 2.4). The ACRL Competencies address every facet of information literacy (Keene, Colvin, and Sissons, 2010). The cycle of completing a research assignment employs every cognitive skill of information literacy. The Colvin-Keene cyclical design ‘emphasizes the relevant cognitive skills exercised by students at each stage of the information cycle’ (Keene, Colvin, and Sissons, 2010). This parallel pattern makes Colvin-Keene a more realistic approach to apply to instructional design of ILI programs in academic libraries.

Accreditation is the most important factor in determining a college’s or university’s academic credibility, and all accreditation agencies have made information literacy a required standard. They have defined the importance of the relationship between information literacy and student learning outcomes. As information literacy has become an important aspect of higher education, the need exists for authentic assessment models to identify learning outcomes in academic library instructional programs. Though there have been increases in measuring the effectiveness of ILI programs, more work needs to be done on measuring the effectiveness of ILI in increasing cognitive outcomes. There are different approaches to assessing this. Measuring cognitive outcomes can occur at any point in the instructional process, before, during, or after. Alternatively, it is done most effectively using a research design similar to the illustration in Table 2.1. Pretest participants in groups that receive the instruction and groups that do not, administer the instruction, and posttest both groups. There are also different measurement instruments. Comparable to measuring behavioral outcomes, interviews and focus groups can be used, though the same limitations apply. Knowledge tests and performance assessments are most commonly used, and both can provide effective and accurate results.

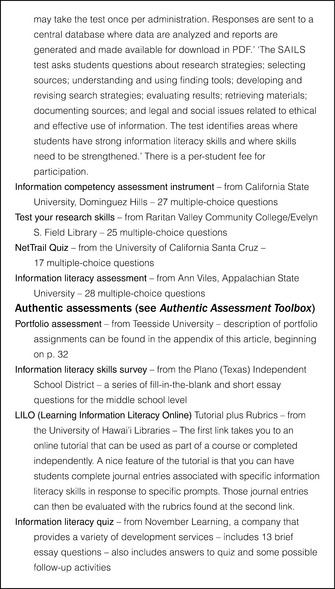

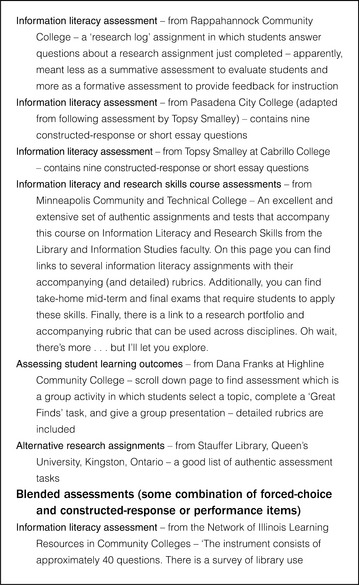

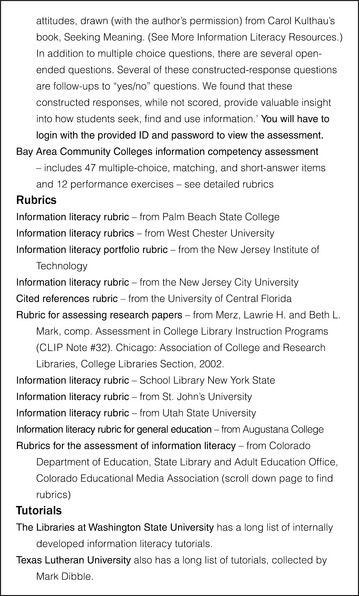

Knowledge tests and performance assessments developed in-house can require enormous resources, and many institutions consider ready-made solutions. Standardized information literacy tests have been developed by some prominent organizations and are designed to measure many different standards including the ACRL Information Literacy Competency Standards of Higher Education. The tests come in a variety of forms and levels, including measurements of real-life experiences that will determine a more ‘authentic assessment experience’ (Grassian and Kaplowitz, 2009). Figure 2.5 presents a list of standardized tests created by a professor of psychology at North Central College in Illinois, Jon Mueller. The list provides the name of the test and the institution that created the test, and includes a short description. The list includes two tutorial resources with embedded assessment that measures student learning in the course of the instruction (Mueller, 2010). Many similar tutorials can be found on the Internet.

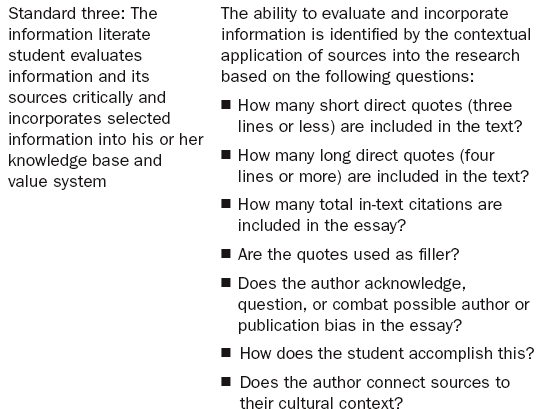

Sue Samson, a Professor and Head, Information and Research Services at the Mansfield Library of the University of Montana, recently developed an effectiveness measuring instrument for the Mansfield Library instructional program. It is a standardized test that quantifies cognitive learning outcomes and is based on the ACRL Standards. Like many measurement instruments, Samson bases assessment on a completed research assignment or paper. Papers of a group of students who received instruction are collected and analyzed. Based on the ACRL Standards, the instrument assesses the performance indicators of each of five standards with quantifiable measures. Table 2.5 shows how the test measures each standard, with a list of questions used to quantify some of the competencies (Samson, 2010). The results of the test need to be recorded and input into a statistical software for analysis. The method has been scientifically proven to be a valid and accurate test for measuring cognitive outcomes of students.

There are many advantages to using cognitive outcomes as an effectiveness standard, and standardized testing can be beneficial beyond measuring the effectiveness of your program. They offer an answer to making information literacy assessment a foundational element of the educational process within higher education. Grassian and Kaplowitz claim ‘many educators and librarians are looking toward these tools as possible ways to have IL assessment become a standard part of our educational system’ (Grassian and Kaplowitz, 2009). Results of the tests can be used in many ways to advance the library. The tests can be used as input measures before students enter a certain level of education or class and as indicators of progress toward a major or a graduation competency, and are a good measurement instrument to test the long term impact of ILI programs (Grassian and Kaplowitz, 2009).

Affective outcomes

The promotion of the importance of assessing cognitive outcomes has overshadowed the need for measuring the affective outcomes of ILI, and these types of outcomes have largely gone unnoticed throughout higher education. Robert Schroeder and Ellysa Cahoy are two members of the committee responsible for revising the ACRL Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education document. They claim ‘higher education information literacy standards have readily addressed cognitive skills, although affective competencies - the emotional abilities that students must acquire in order to successfully navigate the research process - have not yet been incorporated into standards’ (Schroeder and Cahoy, 2010). The lack of attention most likely stems from the difficulty in codifying and measuring affective outcomes. Schroeder and Cahoy believe defining affective outcomes can be confusing and elusive, writing, ‘by its very nature, the realm of affect is more ambiguous, less logical, and less clearly defined than the cognitive domain’ (Schroeder and Cahoy, 2010). Table 2.6 lists a set of terms collected by Schroeder and Cahoy used to describe the concept of affective outcomes. From these terms Schroeder and Cahoy have formulated this working definition: ‘The affective domain comprises a person’s attitudes, emotions, interests, motivation, self-efficacy, and values’ (Schroeder and Cahoy, 2010). The challenges of measuring affective outcomes may derive from the fact that they involve a student’s behavior and confidence level toward learning something before and after instruction - not how well they have learned from instruction. Measuring affective outcomes is a different, more psychological approach than evaluating the effectiveness of ILI and has to do with personal feelings an individual has toward a particular experience. Affective experiences refer to a person’s emotional reactions that he or she experiences during task performance (Ren, 2000). The two most common experiences related to task performance using library skills are self-efficacy and library anxiety. ILI is used to increase participants’ self-efficacy and decrease library anxiety.

Table 2.6

Terms associated with the concept of affect by various authors

| Attitudes | Attitudes | Attitudes |

| Interests | Beliefs | Beliefs |

| Sentiments | Emotions | Interests |

| Values | Perceptions | Openness |

| Psychosocial | Needs | |

| responses or | Opinions | |

| behaviors | Personal | |

| Sensations | temperament | |

| Values | Social temperament | |

| Values | ||

| Jum C.Nunally | William J. Gephart | Ralph Hoepfner |

| Activities | Attitudes | Appreciations |

| Assumptions | Attitudes about self | Biases |

| Attitudes | Attributions | Degree of acceptance |

| Beliefs and | Continuing motivation | or rejection |

| convictions | Emotions | Emotion |

| Feelings | Feelings | Emotional sets |

| Goals or purposes | Interest | Feeling tone |

| Interests | Morals and ethics | Interests |

| Worries, problems | Self-development | Values |

| obstacles | Social competence | |

| Values | ||

| Louis Edward Raths | Barbara L. Martin | David Krathwohl |

Source: Schroeder and Cahoy, 2010

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in having the required skills to perform a given task (Cassidy and Eachus, 1997). Noted social psychologist Albert Bandura defined it as ‘a belief in one’s own capabilities to organize and execute the course of action required to attain a goal’ (Bandura, 1998). It is the confidence one has in doing something, and it is the foundation of motivation for just about everything humans do (Kurbanoglu, 2009). If a person believes they cannot do something, there is very little incentive to act or persist in completing a task. Bandura believes that possession of the necessary skills only fulfills half the requirements in completing a given task. He claims that an individual must also have the self-confidence to use the skills effectively in order to successfully complete the task (Bandura, 1997; Kurbanoglu, 2009). Low levels of self-efficacy will most likely lead to failure, when the individual believes the task is insurmountable and has no ambition to continue. However, individuals with a high level of self-efficacy in a certain skill will continue at a challenging task, anticipating eventual success, and persist until they succeed. Serap Kurbanoglu, an information management professor at Hacettepe University in Ankara, Turkey, claims that besides learning information literacy skills, individuals in today’s societies must also develop confidence in the skills that they are learning. Many of today’s students lack self-efficacy when confronted with using library resources. They do not see library resources, especially electronic databases, as being straightforward or easy to use. They are used to Internet search engines such as Google and when confronted by failures in their search strategies using library databases, usually give up (Waldman, 2003). Karbanoglu writes, ‘attainment of a strong sense of self-efficacy beliefs becomes as important as possessing information literacy skills’ (Kurbanoglu, 2009). Students who believe they can access and use information effectively will do so effectively.

Though the study of the effects of ILI on self-efficacy is limited, the research has shown that information literacy instructional sessions are effective in improving students’ self-efficacy in using the library and its resources (Martin, 1989; Ren, 2000; Nahl-Jakobovitz, 1993). A study performed by Wen-Hau Ren, a librarian at Rutgers University in New Jersey, showed a significant increase in student self-efficacy in using the library’s electronic databases after instruction. In an article describing her study she writes, ‘This study shows that college students’ self-efficacy in electronic information searching was significantly higher after library instruction’ (Ren, 2000). The effectiveness of the instruction was measured with pre- and posttest surveys. The surveys contained four sections: (1) self-efficacy in using library electronic sources; (2) attitudes toward acquiring online search skills; (3) use frequency of computer, e-mail, the Internet, and library electronic databases; and (4) individual background information. The posttest survey questionnaire was filled out by the students after they submitted the library assignment. The second questionnaire contained the same first two sections in the preinstruction questionnaire.

Additionally, it asked the participants to assess their electronic searching performance and report any negative emotions experienced when completing the assignment. Thirteen tasks/skills were listed in regard to searching the library online catalog, online periodical databases, and the library’s website. Students were asked how confident they were at performing each task and confidence levels were rated on a 10 point scale, with 1 being not confident and 10 being very confident. Students were also asked to self-assess their own searching performance as well as being evaluated by a librarian. Results determined that the instruction was not only effective at increasing the students’ technical skills, it also cultivated and improved the self-efficacy of the students, increasing learning outcomes.

A similar 2005 study carried out at the University of Central Florida confirmed the effectiveness of ILI in increasing students’ self-efficacy. Two UCF librarians, Jenny Beile and David Boote, conducted research comparing web-based instruction with face-to-face instruction and found that, regardless of the method, self-efficacy levels increased across all groups (Beile and Boote, 2005). The effectiveness was measured by surveys that evaluated self-efficacy (see Figure 2.6). ‘Self-efficacy scores were determined by responses on a library skills self-efficacy scale. Participants responded to statements such as, ‘I can identify equivalent or related search terms’, and ‘I can search for books by author in the library catalog’, or ‘I can easily differentiate between primary and secondary resources by indicating how strongly they agreed with the statement on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree)’ (Beile and Boote, 2005). An analysis of the results showed a significant improvement in self-efficacy levels and proved that repeated exposure to ILI offers even more positive effects on self-efficacy levels. The researchers suggested that, within the context of library skills, increased levels of self-efficacy are positively related to greater learning outcomes. These findings are consistent with other studies measuring the effectiveness of instruction in increasing self-efficacy levels and the increases having a positive correlation with increasing student learning outcomes. As mentioned, measuring affective outcomes such as increases in self-efficacy levels can be difficult; however, as Beile and Boote recommend in their discussion, ‘these and other similar findings suggest librarians would do well to attend to the affective domain as well as the cognitive’ (Beile and Boote, 2005). Self-efficacy is an individual’s belief in the ability to perform a given task. Bandura’s self-efficacy research showed that individuals’ belief systems affect their behaviors and how much they are willing to do to succeed in the informationseeking process. Self-efficacy is a predictor of research achievement (Mellon, 1986) and should be considered an important alternative approach when evaluating the effectiveness of ILI.

Library anxiety

Library anxiety is common among college students and is characterized by feelings of inadequacy and negative emotions including tension, fear, and mental disorganization (Jiao and Onwuegbuzie, 1999). It is not mutually exclusive to college students and academic libraries. In fact, when faced with using library resources to fulfill information needs, most people in all types of libraries suffer from confusion and uncertainty, especially with a difficult, complex information-seeking assignment (Battle, 2004). Constance Mellon, a library science professor at the University of North Carolina, was the first to identify and define students’ apprehension in using the library as library anxiety. She described it as an uncomfortable feeling or emotional disposition experienced in a library setting that has cognitive, affective, physiological, and behavioral ramifications (Mellon, 1986). Library anxiety has foundations in self-efficacy and is due to students’ belief that they do not possess the required skills to complete a research assignment. It can have a damaging effect on student learning and a long-term harmful effect on a student’s academic career. Most often the anxious feelings develop from intimidation at the size and complexity of the library. The library’s resources do not seem to be as friendly and intuitive as the commercial search engines that students are familiar with. Other common causes stem from student unpreparedness and the increasing non-traditional and international element of current student populations. There has been much research conducted in the field since Mellon’s identification and most results show the best intervention for reducing students anxiety is ILI (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2004).

The most effective way to reduce library anxiety is to first identify the students who are experiencing anxiety, then have them attend library instructional sessions that emphasize affective skills development and search strategies (Jiao and Onwuegbuzie, 1997). Sharon Bostick, a former director of the University of Massachusetts, Boston Library, identified five different antecedents of library anxiety, namely barriers with staff, affective barriers, comfort with the library, knowledge of the library, and mechanical barriers. In the early 1990s she developed a measuring tool to determine levels of anxiety in students called the Library Anxiety Scale (LAS). The LAS has been the only widely used instrument to measure library anxiety. The LAS is a 43 item, 5 point Likert type format which measures levels of library anxiety. The 43 items are grouped into the 5 antecedents used to determine what barriers are causing a student’s anxiety. Figure 2.6 shows the 43 questions, each followed by the numbers 1–5, with 1 meaning ‘Strongly disagree’ and 5 ‘Strongly agree’. Bostick claims the fact that this is the only instrument to date to be utilized in measuring library anxiety suggests that other measuring standards are needed to incorporate the expansion of environments. She writes, ‘The most significant changes in the library and information field during the last decade have been the transition from location-specific information environments to the more open, virtual information settings’ (Onwuegbuzie, Jiao and Bostick, 2004). New questions should attempt to determine a participant’s level of comfort with electronic environments, including use of web-based resources and other computerized aspects of research. Onwuegbuzie, Jiao and Bostick suggest researchers also need to administer the scale at specific times relevant to a participant’s highest anxiety levels, such as just after an assignment is given to the student and before the research is started. They suggest this type of intervention before research starts will contribute to the outcomes and provide a more accurate measurement of anxiety before and after library use.

The task of measuring affective outcomes has proved to be very challenging to researchers. Though it seems to be one of the most appropriate measures of effectiveness, few researchers have attempted to measure students’ thoughts and feelings about using the library. This pattern must change; self-efficacy and library anxiety are most likely the greatest deterrents of library use. Reducing anxiety and increasing participant confidence in their library skills should be written as goals and objectives of every academic library instructional program (Kurbanogul, 2009). Measuring levels of anxiety and efficacy will help identify students who require the most assistance. Academic librarians need to define new methods that are effective in measuring anxiety and efficacy and new instructional methods that reduce the former and increase the latter.

Take-home message

This chapter defined the different categories an ILI program can use to determine its success and effectiveness. Whether measuring behavioral, cognitive, or affective outcomes, remember that all assessment is beneficial to the library and its participants. Assessing instructional effectiveness by measuring outcomes is vitally important to the success of a library’s instructional program. It is the best way to determine the effectiveness of the program and it can help improve an instructional program. Assessment can expose areas not contributing to the advancement of student learning and areas that do not support the library’s goals. Increased library use denotes increased student learning, less anxiety promotes use, and students having the confidence to do it on their own increases learning skills. Measuring effectiveness can point a library in the right direction. Grassian and Kaplowitz believe assessing the library’s instructional program can lead to the advancement of the program and its position with the institution. They write, ‘Assessments can be used to provide information on the effectiveness of new and existing ILI programs’ (Kaplowitz and Grassian, 2009). Assessment results can be shown to administrators and budget committees and ‘This is a way for the library to document its contributions to the institution, to the goals and mission of the parent organization, and the advancement of student learning’ (Kaplowitz and Grassian, 2009). Choosing a method of assessment is just as important as choosing an instructional method. As a library begins making decisions on a method of instruction, it should also be choosing a way to measure its effectiveness and criteria for success.

References

Algon, J., Classifications of Tasks, Steps, and Information-related Behaviours of Individuals on Project Teams. In Jannica Hiensrtom’s dissertation ‘Fast Surfers, Broad Scanners and Deep Divers. Personality and Information-seeking Behaviour., 1997. Available at. http://participants.abo.fi/jheinstr/parmbild.pdf

Anderson, L.W., Krathwohl, D.R., A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing. a Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman.. 2001. [Eds.].

Association of College, Libraries, Research, Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education. 2000. Available at. http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/acrl/standards/informationliteracycompetency.cfm

Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: W.H. Freeman; 1997.

Battle, J., The Effect of Information Literacy Instruction on Library Anxiety among International Students. Doctoral dissertation, U of North Texas, May, 2004. Proquest Information and Learning Company, 2004. [3126554.].

Beile, J., Boote, D. Does the Medium Matter?: A Comparison of a Web-based Tutorial with Face-to-Face Library Instruction on Education Students’ Self-efficacy Levels and Learning Outcomes. Research Strategies. 2005; 20:57–68.

Cassidy, S., Eachus, P. Developing the Computer Self-efficacy (CSE) Scale: Investigating the Relationship Between CSE, Gender and Experience with Computers. Journal of Educational Computing Research. 1998; 26(4):133–153.

Grassian, E., Kaplowitz, J. Information Literacy Instruction: Theory and Practice. New York, NY: Neal-Schuman; 2009.

Hiensrtom, J., Dissertation. Fastsurfers, Broad Scanners and Deep Divers. Personality and InformationSeeking Behavior. 2002; Available at. http://participants.abo.fi/jheinstr/parmbild.pdf

Hotchkiss, P., Personal interview at Cochise College Library with Director of Libraries. 2007.

Hotchkiss, P., Personal interview at Cochise College Library with Director of Libraries. 2009.

Jiao, Q.G., Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Antecedents of Library Anxiety. Library Quarterly. 1997; 67(4):372–389.

Jiao, Q.G., Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Self-perception and Library Anxiety: An Empirical Study. Library Review. 1999; 48(3):140–147.

Keene, J., Colvin, J., Sissons, J., Mapping Student Information Literacy Activity against Bloom’s Taxonomy of Cognitive Skills. Journal of Information Literacy. 2010; 1(4):6–20 Available at. http://ojs.lboro.ac.uk/ojs/index.php/JlL/ article/view/PRA-V4-I1-2010-1

Krikelas, J. Information Seeking Behavior: Patterns and Concepts. Drexel Library Quarterly. 1983; 19(2):5–20.

Kurbanoglu, S., Self-efficacy: An Alternative Approach to the Evaluation of Information Literacy. 2009. Available at. http://www.isast.org/proceedingsQQML2009/PAPERS_PDF/Kurbanoglu-Self_Efficacy_An_Alternative_Approach_to_ the_Evaluation_of_IL_PAPER-QQML 2009.pdf

Limberg, L. Information Use for Learning Purposes. Broad: In Jannica Hiensrtom’s dissertation ‘Fast Surfers; 1997.

Scanners and Deep Divers Personality and Informationseeking Behaviour.’ Available at http://participants.abo.fi/jheinstr/parmbild.pdf.

Martin, B.L. A Checklist for Designing Instruction in the Affective Domain. Educational Technology. 1989; 29(8):7–15.

Mellon, C.A. Library Anxiety: A Grounded Theory and Its Development. College and IResearch Libraries.. 1986; 47:160–165.

Mueller, J., Information Literacy Assessment. Available Online. North Central University. 2010 Available at. http://jonathan.mueller.faculty.noctrl.edu/infolit assessments.htm

Nahl-Jakobovits, D., Jakobovits, L.A. Bibliographic Instructional Design for Information Literacy: Integrating Affective and Cognitive Objectives. Research Strategies. 1993; 11:73–88.

National Postsecondary Education Cooperative (NPEC)., NPEC Sourcebook on Assessment. Definitions and Assessment Methods for Communication, Leadership, Information Literacy, Quantitative Reasoning, and Quantitative Skills. and Quantitative Skills., 2005. Available at. http://nces.ed.gov/pubs20052005832.pdf

North Central Association of Colleges, Schools. The Higher Learning Commission, Handbook of Accreditation (2nd ed). 2003. Available at. http://www.ncahigherlearningcommission.org

Northern Illinois University Office of Assessment Services. A History of Assessment. Available at http://www.niu.edu/assessment/Manual/history.shtml, 2010.

Onwuegbuzie, J., Jiao, Q., Bostick, S. Library Anxiety: Theory, Research, and Applications. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press; 2004.

Radcliff, C., Jensen, M., Salem, A., Burhanna, K., Gedeon, J., A Practical Guide to Information. 2007.

Literacy Assessment for Academic Librarians. Westport, C T: Libraries Unlimited Publishing.

Ren, W. Library Instruction and College Student Self-efficacy in Electronic Information Searching. The Journal of Academic Librarianship. 2000; 26(5):323–328.

Samson, S. Information Literacy Learning Outcomes and Student Success. The Journal of Academic Librarianship. 2010; 36(3):202–210.

Saunders, L. Regional Accreditation Organizations’ Treatment of Information Literacy: Definitions, Outcomes, and Assessment. The Journal of Academic Librarianship. 2007; 33(3):317–326.

Schroeder, R., Cahoy, E. Valuing information literacy: affective learning and the ACRL standards. Portal: Libraries and the Academy. 2010; 10(2):127–146.

Simmonds, P.L., Andaleeb, S.S. Usage of academic libraries: The role of service quality, resources, and participant characteristics. Library Trends. 2001; 49(4):626–634.

Trombley, W., The rising price of higher education. College affordability. 2003. Available at. http://www.highereducation.org/reports/affordability_supplement/

Waldman, M., Freshmen’s Use of Library Electronic Resources and Self-efficacy. Information Research. 2003 8(2), paper no. 150. Available at. http://informationr.net/ir/8-2/paper150.html