The depths and heights of business sustainability

Abstract:

This chapter introduces the essence of business sustainability from a broad and integrated approach to business, encapsulating people, prosperity and planet – our 3Ps. It also introduces the concept of a business’ ‘life’ with the objective to reaffi rm an organisation’s linkages with the philosophies of life. It highlights the fact that successful and sustainable organisations have formed their basis of sustenance through ‘karma’, consequently creating and strengthening the basis of ‘immortalising’ their businesses.

Introduction

New business infrastructure and competitive human capital (Rowley and Redding 2011) within a dynamic labour market are some of the factors that lead organisations to make radical shifts and redefine their business strategies and enhance people management practices (Rowley and Harry 2011). Addressing these developments efficiently means organisations have to strike a balance with their limited resources and constraints as they work towards business excellence and sustainability (SHRI 2009).

What is business sustainability all about? How can businesses remain sustainable? What are some of the impacts of globalisation on the sustainability of businesses? Is it feasible for businesses to continue to prosper for long periods of time? Can businesses draw lessons from ancient civilizations? Is there a way to measure and predict the business sustainability of organisations? This chapter examines these questions and issues and helps suggest some possible answers.

The structure of the rest of this chapter is as follows. We have five further sections covering: the context of globalisation; organisational life cycles and factors affecting business sustainability; bottom lines in business sustainability; a business sustainability continuum; metrics and measures of business sustainability. These sections are followed by a conclusion.

Business sustainability and globalisation

The word sustainability is derived from the Latin word sustinere (tenere, to hold). Sustainability is seen as by some as: ‘at the intersection of environmental, economic, and societal stewardship’ (ASU n.d). The concept of sustainability was defined by the Brundtland Commission of the United Nations as: ‘development which meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (Brundtland 1987: 8). This is a widely quoted definition of sustainability and sustainable development.

Globalisation has a long history, both in its meanings, practices and debates. It often describes international economic competition and its impact on ‘connectedness’, specifically, the increasing trans-boundary flows of goods and services, including not only materials, but also information, environmental pollution and people.

The meaning and newness of globalisation is contested (see Rowley and Benson 2000). There are a variety of ways of viewing globalisation. It can be taken as involving both macro and micro aspects. On one hand there is a process of integration of national economies, while on the other hand there are significant changes in markets (product and financial), assisted by their common liberalisation and deregulation.

As with many concepts, there is rarely a universally accepted and commonly-used definition of globalisation and trying to more tightly pin-down its ‘meaning’ is problematic (Amin and Thrift 1996). For some it is a ‘process of extending interdependent cross-border linkages in production and exchange’ (Kozul-Wright 1995: 139). For others it is the integration of national economies in terms of trade and investment, with erosion of barriers (including to FDI and ‘outsourcing’) increasing capital mobility (Harcourt 2000). Globalisation can indicate the internationalisation of production, trade and markets and the integration of domestic economies into global economies (Burgess 2000). For others (Zhu and Fahey 2000) globalisation reflects the three integration processes of:

1. financial and currency markets;

2. production, trade and capital formation across national boundaries;

3. functions of global governance partially regulating national economic, social and environmental policies.

Also, globalisation is associated with growing internationalisation of the processes of production and finance with the decline of states and the importance of national politico-economic entities (Hadiz 2000). Importantly, we need to distinguish between financial and manufacturing globalisation because of the latter’s lower mobility, longer-term focus and more direct impact on employment (Bhopal and Todd 2000).

As a simple, broad, encompassing working definition we would suggest globalisation here be seen as an erosion of the political, social and economic boundaries of nation states and markets. This does not attach reasons for globalisation, but does point to a number of key issues, such as the influence of MNCs (via FDI etc.); limitations on national laws to protect labour; a power shift towards capital; difficulties for labour organisations and trade unions in attempting to influence the process; and the level at which action needs to be taken. In short, while globalisation is a process driven by technology, sustainability seems very clearly to reflect a perception of our role in the history of nature (Runge 1997).

The above definitions and approaches make one thing very clear – that sustainability and globalisation are not contemporary scenarios, but rather have been there all through civilisations, including as far back as Ancient Rome. The main difference to this today is technological advancement and the current context, leading to increases in the frequency of such happenings and making the overall phenomenon more complex. Therefore, the issue of sustainability of businesses under globalisation actually involves another look into the fundamentals in the current context.

Life expectancies of organisations

Business sustainability may be described as cohesively managing and integrating the financial, social and environmental facets of the business. It is about creating long-term stakeholder value. Yet, how long is long? Some authors (such as de Geus 2002) talk about a company (or business) as a ‘living entity’ that has its own unique characteristics. Thus, it may be inferred that business sustainability is equivalent to the life expectancy of an organisation. There is a long stream of research applying naturalist ‘life cycle’ concepts, with birth, growth, maturity and decline (and death), to different aspects of business, from products to companies and industries (Vernon 1966,1979;Hirsch 1967; see reviews in Rowley 1994,1998,1998,2000). These terms remain in common parlance.

What then is the average life expectancy of an organisation? The Shell study described in de Geus (2002) calculated the average life-expectancy of a large MNC to be 40–50 years. However, this study only included companies that had already survived their first 10 years, commonly a period of high corporate mortality. A study by Stratix Consulting Group calculated the average life expectancy of firms in Japan and much of Europe, regardless of size, at 12.5 years (de Rooji 1996). Another study indicated the average life span of companies to be 12–15 years (Hewitt 2004). It is worrying to look at the above figures and grasp that the average life of a company is so short.

On the other hand, some organisations are still around after very long periods of time. For example, Beretta, the Italian firearms maker, is 500 years old and Giraudan the Swiss perfumery was established in 1895 (see our later case study). A 2009 study by Tokyo Shoko Research Ltd (in Breitbart 2009) notes that among nearly 2 million (1,975,620) firms in Japan 21,066 firms were founded more than a century ago and eight firms were founded more than 1,000 years ago, with Osaka-based construction company Kongo Gumi topping the list with 1,431 years of history. There are also other examples, such as South Korea, and elsewhere in the world (see Table 2.1).

There were 3,146 firms founded over 200 years ago in Japan, 837 in Germany, 222 in the Netherlands and 196 in France (Kim 2008). Japan’s construction company Kongo-gumi was established in 578. Regarding the reason for the longevity of Japanese firms, it has been suggested that they focused on their core businesses by accumulating and developing unique skills and know-how, based management on the trust of stakeholders, and established a professional CEO system and conservative management (Kim 2008). Korea’s oldest firms date from the late 1890 s, Doosan in food and beverages and Dong Wha Pharmaceuticals (Kim 2008). Cases like these prompt the view that a ‘natural’ average lifespan of an organisation can be much higher than the more recent averages may, at first sight, imply.

Does that mean there is an urgent need look again into the entire concept of sustainability? Why be concerned about business sustainability at all? It is because, as de Geus (2003: 3) states: ‘the damage that results from the early demise of otherwise successful companies is not merely a shuffle in the Fortune 500 list, work lives, communities, and economies are all affected, even devastated, by premature corporate deaths.’ Is there, then, a way for organisations to increase the length of their lives? We look at this next.

Business longevity

The Bhagavad Gita, the sacred Hindu scripture enumerates that the soul of no living entity dies. The following is noted in chapter 2, verses 22 and 23 respectively.

(Vasansijirnaniyathavihayanavanigrihnatinaroaparnai, thatasariranivihayajirnanyanyanisanyatinavanidehi, Bhagwad Gita, chapter 2, verse 22).

Meaning – Just as a man giving up old worn out garments accepts other new apparel, in the same way the embodied soul giving up old and worn out bodies verily accepts new bodies.

(NainamChindantiSastrani, nainamdahatipavaka, nachainamkledayantiapo, na so sayatimahruta, Bhagwad Gita, chapter 2, verse 23).

Meaning – Weapons cannot harm the soul, fire cannot burn the soul, water cannot wet and air cannot dry up the soul. The soul is eternal.

Drawing lessons from the above and considering the fact that organisations are living entities, it may be inferred that business sustainability has two different phases. These are as follows.

1. When the business has its physical existence – this is driven by karma (‘action’ or ‘deed’). This karmic phase is responsible for shaping the future.

2. When the business leaves a legacy behind – based on the previous karmic phase. This stage is the phase beyond physical existence of the business or post-karmic phase. The product, artefact, creation and thoughts are implanted in future generations.

The karmic and post-karmic phases of business sustainability are further explained through the following examples. In the late 1800 s Marconi developed the radiotelegraph system, which served as the foundation for the establishment of numerous affiliated companies worldwide (Roy 2008). In 1902 a transmission from the Marconi station in Nova Scotia, Canada became the first radio message to cross the Atlantic from North America (Eaton and Haas 1995). Another example concerns three of Thomas Edison’s inventions – the phonograph, a practical incandescent light and electric system and a moving picture camera – which helped found giant industries that changed the life and leisure of the world. For instance, by 1890 Edison had brought together several of his business interests under one corporation to form Edison General Electric. At about the same time the Thomson-Houston Company, under the leadership of Charles A. Coffin, gained access to a number of key patents through the acquisition of a number of competitors. Subsequently, General Electric was formed by the 1892 merger of Edison General Electric and Thomson-Houston Company (GE n.d.). The organisation sustained for over a century, carrying forward the legacy and also became one of the world’s largest companies (Forbes 2009). These examples are able to reinforce the fact that every organisation, like humans, has a choice and the potential to live through the karmic phase, creating products or services that will form the basis of the sustainability of the organisation, even after its mere physical existence. The sustainability of business, thus, can be in its ‘immortalisation’, or longevity consciously created through karma.

Factors affecting the sustainability of business

Now that the karmic and post-karmic phases of an organisation have been outlined, there is a need to understand the factors that may affect the sustainability of a business in the karmic phase. As mentioned previously, the foundations of the post-karmic phase will be developed when the organisation has its physical existence. Broadly speaking, there are two factors that affect business sustainability when an organisation has its physical existence, or is in the karmic phase. These are as follows:

1. ‘Regular Maintenance’ – this helps the organisation to run on a day-to-day basis and acquire strength for any contingencies that may crop up in the future.

2. ‘Withstanding Contingencies’ – this is an organisation’s ability to withstand any unforeseen challenges that may hinder the business operations and remain invincible.

As Tracy (2008: 138) notes: ‘Perhaps the greatest enemy of personal success is explained by the Law of Least Resistance. Just as water flows downhill, most people continually seek the fastest and easiest way to get what they want, with very little thought or concern for the long-term consequences of their behaviour. This natural tendency of people to take the easy way explains most underachievement and failure in adult life.’ Does this mean that the uncertainties of the future are created due to the selfishness of a few people governed by the law of least resistance? Assuming the present is the testing ground of future consequences, are we able to then control the present and determine the future to make it sustainable? One interesting insight into human tendency is put metaphorically: ‘in Mayan mythology, the Universe was destroyed four times, and every time the Mayans learned a sad lesson and vowed to be better protected but it was always for the previous menace … 2,000 years later we are still looking backward for signs of the upcoming menace but that is only if we can decide what the upcoming menace is’ (Lynch and Rothchild 2000: 86–7).

Yet, of course, predicting the future has limitations; it is probably best to make a business more fundamentally strong so that it can withstand adversities and contingencies rather than triggering distress calls (such as ‘SOS’ or ‘Save Our Souls’). On the contrary, revisiting fundamentals may provide options as to whether to continue to succeed or fail and go under. This in turn requires answering questions about what the bottom line in business sustainability is.

Bottom lines in business sustainability

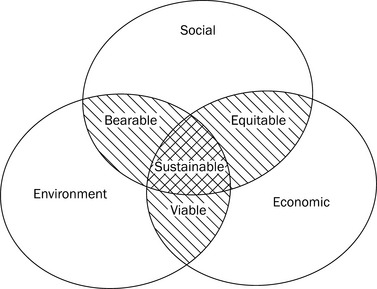

Any uncertainty a business faces will heighten the stance of any organisation to be vigilant and creative to stay relevant and sustainable. It is a holistic picture of how businesses should strive to achieve the TBL of balancing the overlapping and inter-acting economic, environmental and social factors of the organisation, given the human capital at hand. This mix can be seen diagrammatically in Figure 2.1.

Sustainable development is often presented as an attempt to reconcile three types of constraints: economic, social and environmental. This takes into account the interactions between them and how they contribute towards development that is: equitable (sharing of economic resources among the citizenry), viable (compliance with environmental needs), and bearable (socially and humanly acceptable) (Biaye 2010). Thus, the three objectives of the TBL – economic well-being, environmental health and social equity – requires viability from the economic and environmental point of view; equity from the economic and social point of view and being bearable from the environmental and social point of view. These are represented in our diagram (see Figure 2.1) with ‘sustainability’ being the ‘sweet spot’ where the three constraints mentioned above are balanced.

The 1990s witnessed the emergence of ‘sustainability’ as a corporate strategy. Early on the Business Council for Sustainable Development, a group of executives from major MNCs, such as Dow Chemical, DuPont and Royal Dutch/ Shell, expressed concern at the emerging environmental crisis and appealed for a change among MNCs – for them to break with conventional values and ways of doing business.

Businesses, as a result of their evolution and experiences in adverse economic conditions, began to realise that business sustainability was actually more about ensuring long-term business success encompassing the 3Ps of people, prosperity and planet. To be successful and sustainable, organisations must also focus on the achievable overall progress, which includes benefiting people, promoting prosperity and protecting the planet through innovative ideas (Mukherjee Saha 2009). The 3Ps have in turn been encapsulated in the concept of the TBL. This phrase was coined by Elkington (1998), later expanded and articulated in his book Cannibals with Forks: the Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business (1998). The TBL captures an expanded spectrum of values and criteria for measuring organisational (and societal) success: economic, environmental and social (see Figure 2.1).

The concept of the TBL requires that an organisation’s responsibility is to stakeholders rather than simply to shareholders. In this case, stakeholder refers to anyone who is influenced, either directly or indirectly, by the actions of the organisation. At a high level, TBL sustainability is a values- and ethics-laden vision of the organisation, it is a concept that explicitly acknowledges the importance of relationships between an organisation’s economic performance and its performance in social and environmental terms.

There are many tools available to assess business sustainability practices and policies adopted by various organisations. Rather than giving an ‘either/or’ answer of ‘yes’ or ‘no’, a more graduated picture is needed. Thus, these tools can reaffirm an organisation’s position along a business sustainability continuum, as explained next.

Sustainability continuum

The Oxford dictionary defines a ‘continuum’ as continuous sequences in which adjacent elements are not perceptibly different from each other, but the extremes are quite distinct. A sustainability continuum covers, thus, the various ranges and levels of sustainability practices and policies adopted by organisations.

Furthermore, a Global Sustainability Continuum (GSC) has been developed as a tool to assist organisations gain a more objective, external perspective of their sustainability performance as communicated through their publicly available material (RMIT 2009). A GSC assessment places an organisation in one of five sustainability positions ranging across:

After assessing the level of sustainability, an organisation may be curious to affirm the financial value and worthiness of the sustainability initiatives that they have undertaken. In order to do this, it is useful to have some understanding of various metrics and measurements relating to the dynamics of business sustainability. The next section briefly explains these.

Measures of business sustainability

There are many metrics that organisations, managers and researchers can use to conceptualise business sustainability and assign some financial values to business sustainability investments. For example, some recent research suggests that there are a total of 39 unique measures of sustainability to examine the relationship between business sustainability and financial performance (RNBS 2008).

Thus, sustainability metrics are incredibly varied, reflecting the diverse nature of sustainability itself. Many studies use a single sustainability measure, most commonly something like the following: pollution control or output; environmental, health and safety investments; third party audits or awards; the KLD (KLD Research & Analytics, Inc.) index; and Fortune magazine rankings.

Research Network for Business Sustainability (RNBS 2008) also suggests that there are three categories of metrics that are relevant to sustainability. These are as follows.

1. Financial: these are the end-state metrics with which the market evaluates performance. For example, return on equity from a profitable sustainable product line.

2. Operational: these are the metrics related to sustainability activities and their direct bottom-line impacts. For example, tonnes of waste recycled into manufacturing inputs and subsequent decreased raw material costs.

3. Strategic: these are the metrics that reflect an organisation’s improved position strategically to create value and manage risk. For example, satisfaction rates with a community engagement programme that helped fast-track the regulatory approval process to build a new plant.

Conclusion

In this chapter we briefly outlined globalisation, defined business sustainability and introduced the concept of businesses ‘life’ with the objective to re-affirm an organisation’s linkages with the philosophies of life. The core intention of every organisation is succinctly explained by de Geus (2002: 11) as follows: ‘Like all organisms, the living company exists primarily for its own survival and improvement to fulfill its potential and to become as great as it can be … You exist to survive and thrive; working at your job is a means to that end. Returning investment to shareholders and serving customers are a means to a similar end for IBM, Royal Dutch/Shell, Exxon, Procter & Gamble, and every other company.’ In other words, all these successful and sustainable organisations have formed their basis of sustenance through ‘karma’, consequently creating and strengthening the basis of ‘immortalising’ their businesses.

Organisations often develop expectations to be just economically prosperous. Paradoxically, such short-termism and skewed views often lead to organisational mortality. Organisations do not survive as long as they could. By viewing the whole picture and adhering to TBLs, organisations can remain more sustainable and survive longer. Therefore, businesses and organisations may succeed or fail due to their own behaviour and actions. These ideas are outlined and discussed further in our next chapters.