Appendix: Singapore education and training system at a glance

The vision for Singapore is to be ‘a developed country in the first league’ (MTI 2000). As a small island city-state endowed with no natural resources, Singapore has had to emphasise the human skills of its population and human capital to be economically competitive. The government has, therefore, stressed education and training to enhance the competitiveness of the country.

In 2000 Singapore’s Minister of Education Teo Chee Hean expressed his aspiration to make Singapore the ‘Boston of the East’ (Teo 2000). The education industry already formed an integral part of Singapore’s economy, contributing 3 per cent to GDP in 2000 and by September 2001 there were some 50,000 foreign students on student visas. The Economic Review Committee (ERC) 2002 identified education as one of the service industries to be developed and promoted, not only to cater to local needs but also to a large number of international students studying in Singapore.

The education system in Singapore – the genesis

After the founding of Singapore by Sir Stamford Raffles of the East India Company in 1819, a dual education system developed between English-language schools and vernacular schools that taught in the mother tongue (Chinese, Malay and Tamil).

By the 1860 s it was recognised that schools required financial assistance and the colonial state abandoned its non-interventionist policy by initiating a small number of English-language primary and secondary schools and providing free Malay-language primary education. Grants-in-aid were given to non-government schools but these did not begin on a regular basis until 1920 (Gopinathan 1974). The Winstedt Committee on Industrial and Technical Education (1925) was more forward-looking and highlighted the pressing demand for English-speaking clerks of works, assistant surveyors, road overseers and marine engineers (Wong and Ee 1971). The Straits and Federated Malay States Government Medical School was established in 1905 using funds raised largely by the Chinese community in Singapore and Penang. In 1921 the school was expanded and renamed King Edward VII College of Medicine. In 1929 Raffles College was established to offer courses in the arts and sciences.

After the Second World War the colonial education policy took a dramatic turn in the wake of riots and agitation, particularly among the Chinese, for an end to colonial rule. The Ten Years Program, adopted in 1947, was based on three principles (Gwee 1969):

1. education should be aimed at fostering the capacity for self-government and the idea of civic loyalty and responsibility;

2. equal opportunity for all; and

3. free primary education in English, Chinese, Malay and Tamil.

In 1948, several businesspeople recommended that a proper polytechnic should be set up to train technicians and craftsmen. The Report of the Committee on a Polytechnic Institute for Singapore (1953) recommended the establishment of a polytechnic on four grounds (Tan 1994):

![]() the obvious lack of technical expertise,

the obvious lack of technical expertise,

![]() the breakdown of the traditional apprenticeship system,

the breakdown of the traditional apprenticeship system,

![]() the return of many European engineers to their countries after the war, and

the return of many European engineers to their countries after the war, and

![]() the difficulty in recruiting technicians from the region because immigration laws restricted entry to highly paid foreign workers.

the difficulty in recruiting technicians from the region because immigration laws restricted entry to highly paid foreign workers.

The Singapore Polytechnic was established the following year (1954). On attaining government, the People’s Action Party (PAP) based its education policy on the All-Party Committee’s Report of 1956. This power struggle within the PAP between the Chinese-educated leftists and the English-educated moderates led to an acrimonious split in 1961. In addition, Malay was declared a national language in preparation for the merger with Malaya in 1963. Because of irreconcilable differences Singapore left the federation of Malaysia in 1965.

With the consolidation of power within the PAP, the English-educated professionals continued the colonial emphasis on English-language schools for another reason: to prepare Singapore for the needs of an industrial society.

In 1962 the Singapore division of the University of Malaya became the University of Singapore. Full government recognition of the degrees conferred by Nanyang University came in 1968. In the same year, the degree courses at Singapore Polytechnic were transferred to the University of Singapore, leaving the polytechnic to concentrate on diploma courses and, from 1969, certificate-level courses. Meanwhile, the Ngee Ann Kongsi (a foundation involved in educational, cultural and welfare activities in Singapore) established Ngee Ann College in 1963.

In 1979 a Council for Professional and Technical Education under the chairmanship of the Minister for Trade and Industry recommended a substantial increase in tertiary education (diploma and degree levels) to produce sufficient trained manpower for the Second Industrial Revolution. In 1980, following Sir Frederick Dainton’s Report on University Education in Singapore (1979), the government merged Nanyang University and the University of Singapore to form a single, and stronger, National University of Singapore (NUS) at Kent Ridge.

In his review on Higher Education in Singapore (1989), Sir Dainton argued that, with rapid economic growth and growing demand for graduate manpower, Singapore should build two strong comprehensive universities. Consequently, Nanyang Technological Institute (NTI, established in 1981) was renamed Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in 1991. The National Institute of Education was also established as part of NTU. In 2000 the government set up a third university, the Singapore Management University (SMU), offering courses in management. Presently, the government is looking into setting up a fourth university in Singapore.

It is interesting to note that in Singapore about 65 per cent of the education establishments commenced operations in 1990. Foreign-owned organisations represented 5.9 per cent of the education sector, with an employment share of 3.5 per cent. Some of the more well-known foreign-owned education organisations in Singapore include the British Council English Language Teaching Centre (UK), University of Chicago Graduate School of Business (US) and INSEAD (France).

Singapore education system – policies and practices

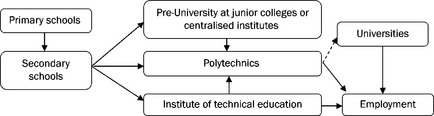

The structure of the education system in Singapore is diagrammatically shown in Exhibit A.1 below. The education at all levels (primary, secondary and tertiary) is flexible and broad-based to ensure all-round or holistic development of the learners.

The Ministry of Education’s 1997 mission statement, ‘Thinking Schools, Learning Nation’ (TSLN), has directed the transformation in the education system in recent years. Since 2003, the Ministry has focused on nurturing a spirit of innovation and enterprise (I&E). In 2004, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong called on the teachers to ‘teach less, so that our students could learn more’, which forms the basis for the TSLN. The Ministry of Education (MOE) also introduced an instructional approach, Strategies for Active and Independent Learning (SAIL) to enhance teaching and learning in schools. The SAIL approach aims to engage students in active and reflective learning, and to nurture independent learning habits (MOE 2001).

Singapore’s local tertiary education institutions are unable to meet existing demand, resulting in a considerable need for international education. There are two types of transnational education in Singapore: ‘external’ distance education programmes and foreign university branch campuses. External programmes are offered in Singapore by a local institution in conjunction with a foreign awarding university, and since the mid-1990s the government has encouraged a select group of elite foreign universities to offer programmes and establish centres.

Singapore has attracted 10 world-class universities, including INSEAD, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Stanford University, Chicago Graduate School of Business, and Technische Universiteit Eindhoven.

The education market is segmented, with demand perceived to come from both consumers (students) and corporations (Singapore is a major base for the regional headquarters of multinational corporations). Singapore’s education industry has progressed from supplying basic academic education to catering to varied needs ranging from personal enrichment, skills building, and professional training.

The government’s annual recurrent spending on foreign students between 2005 and 2008 was estimated at about $154 million in the three publicly-funded universities and about $69 million in the five polytechnics. From 2008, fees for foreign students have been raised from 1.1 to 1.5 times local fees. This provides about one-fifth and one-tenth of the total annual recurrent grants disbursed by MOE to the universities and polytechnics respectively, and is based on the proportion of foreign students in the total student population. The funds go towards operating expenses, including staffing, equipment and other operating expenditures. In return for the subsidies they receive, foreign students are bound by the MOE’s tuition grant obligation, where they have to work at Singapore-based companies for three years after graduation. Those who do not wish to meet this obligation can pay full fees with no public subsidy (MOE 2008).

Singapore Education is a multi-government agency initiative launched by the government in 2003 to establish and promote Singapore as a premier education hub and to help international students make an informed decision on studying in Singapore. This initiative is led by the Singapore Economic Development Board (EDB) and supported by the Singapore Tourism Board (STB), Standards, Productivity and Innovation Board, Singapore (SPRING), International Enterprise Singapore (IE) (all under the Ministry of Trade and Industry – MTI) and the MOE. The key roles of each agency are:

![]() Singapore Tourism Board – Education Services Division

Singapore Tourism Board – Education Services Division

To promote and market Singapore education overseas

![]() Singapore Economic Development Board

Singapore Economic Development Board

To attract internationally renowned educational institutions to set up campuses

![]() International Enterprise Singapore

International Enterprise Singapore

To aid quality schools to develop their businesses and set up campuses overseas

![]() Standards, Productivity and Innovation Board, Singapore

Standards, Productivity and Innovation Board, Singapore

To administer quality accreditation for private educational organisations

The MTI is the most important formal institutional mechanism for governance, with the MOE and the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) following its lead, although in an integrated fashion.

Continuing education and training (CET)

As the Singapore government propounds, education will not just be about pre-work education, but also in-employment, post-work education and continuing education and training (CET) for workers at all levels, and these will become a key focus of national efforts to safeguard the employability of workers. The government has also liberalised the law to promote international cooperation in education and lifelong learning.

The government made further headway in its drive to foster a vibrant intellectual climate when Universitas 21 Global – a consortium of 21 well-known universities and Thomson Learning – established its global headquarters in Singapore in 2001. Not only is the online university the first of its kind in Asia, it adds another dimension to Singapore’s global schoolhouse vision – e-learning (Yeo 2003).

Quality assurance

Singapore has an Education Excellence Framework, designed in 2004 to protect learner interests and to build high-quality education providers and which is aimed primarily at private education organisations (PEOs). The framework focuses on three key components: academic excellence, organisational excellence, and excellence in student protection and welfare practices.

The MTI has established an Education Services Accreditation Council to accredit institutions for their capabilities to deliver quality programmes. The second component of the framework focuses on enhancing the organisational excellence of the PEOs by encouraging them to upgrade through the SQC (Singapore Quality Class) for PEOs Scheme, which provides a benchmark for PEOs in business and management excellence. The third component focuses on PEOs adopting good practices in student protection and welfare through the CaseTrust for Education scheme, which includes the Student Protection Scheme.

CaseTrust is a collaborative accreditation scheme between the Consumer Association of Singapore (CASE), the Building & Construction Authority (BCA), the Economic Development Board (EDB), National Association of Travel Agents of Singapore (NATAS), Singapore Retailers Association (SRA), SPRING Singapore, Singapore Tourism Board (STB) and the Infocomm Development Authority of Singapore (IDA), supported by the MOM, for the accreditation of employment agencies and private education organisations, respectively.

Conclusion

The education system in Singapore revolves around the premise that every learner has unique aptitudes and interests and a flexible approach allows a learner to develop the potential to the fullest. In 2000 the Compulsory Education Act codified compulsory education for children of primary school age, and made it a criminal offence for parents to fail to enrol their children in school and ensure their regular attendance. Exemptions are allowed for home schooling or full-time religious institutions, but parents must apply for exemption from the MOE and meet a minimum benchmark. Special needs children are automatically exempted from compulsory education (QCDA 2008).

As can be noted from the above, Singapore has several competitive advantages that could allow it to position itself as an education hub, including its strategic geographic location, reputation for educational excellence, its vibrant business hub, and a safe and cosmopolitan environment. Singapore’s education system has been described as ‘world-leading’ and in 2010 was among those picked out for commendation by the British education minister Michael Gove (Baker 2010).

Adapted from:

Mukherjee Saha, J. and Ang, D. (2008) ‘Challenges and opportunities in the in-employment education market’, Ch. 9 in Christopher Findlay and William Tierney (eds), The Globalisation of Education: the Next Wave, World Scientific, USA.