Influence: The Bedrock of Leadership

In July of 2016, the CEO of Southern Coos Hospital in Brandon, Oregon, was terminated, prior to the completion of the 18-month extension that he had been awarded. The board cited concerns that the staff had regarding the CEO’s leadership style (Gooch 2016).

In January of 2017, the Summa Health CEO resigned after receiving a no-confidence vote by 240 physicians. Cited among the grievances was that he was making significant changes to the health system without consulting physicians about the impact those changes would have on patient care. As a leader, his lack of engagement with those for whom he was responsible ultimately led to his downfall (Garrett 2017).

In June of 2017, the community of Martha’s Vineyard was rocked by the news that the CEO of their local hospital had been terminated after only 13 months on the job. Among the reasons for his termination were concerns about his ability to listen to and collaborate with the board, a resultant loss of confidence in him by board members, and questions about who was making the ultimate decisions (Wells 2018).

In October of 2017, the Air Force terminated the medical squadron commander of the 62nd Medical Squadron at Lewis-McChord base in Washington state. He was terminated for concerns about his fairness, favoritism, poor morale in his squadron, and his tendency to promote his religion in ways that made his airmen feel uncomfortable (Losey 2017).

In March of 2018, Brookline Trauma Center terminated their physician-founder of 35 years for accusations of employee mistreatment and creating a hostile work environment. He was accused of bullying and making employees feel denigrated and uncomfortable (The Lowell Sun 2018).

In all of the foregoing cases, the terminated health care executive failed to recognize that leadership is about more than title, position, or power. In each of these cases, the leader failed to engage others effectively in decision making, demonstrated an authoritarian command-and-control management style, or pushed a personal agenda that was not in the best interest of the organization. What each of these unsuccessful executives failed to understand is that leadership is about being able to create a followership not a dictatorship. This followership is with subordinates, superiors, peers in the organization or community, and other individuals who are critical to the success of the enterprise. The capabilities of the team are far greater than those of the individual. Leadership is about influence and leveraging the skills, capabilities, and knowledge of those with whom you work. Demonstrating power and authority alone is not successful management behavior for the long term.

Leveraging human capital capabilities within an organization requires more than simply setting an agenda, providing clear roles and responsibilities, or getting everyone strategically “on the same page.” In fact, although all of these tactics are important in accomplishing major organizational initiatives, if the workforce is not engaged, the business will suboptimize or even fail. Engaging a workforce is the most essential, and fundamental, role of any leader. Successful leaders always have engaged organizations. Having people wanting to work for you, and not simply having to work for you, is the secret sauce of effective leadership. Employee engagement is a by-product of effective leadership influence, not, as many would expect, either power or authority (Beard and Weiss 2017; Roth and Conchie 2008; Sinek 2009).

Engaging the workforce and using the best leadership style is not simply a contrived program du jour invented by human resources. There are actual financial benefits for adopting an engaging style. In one of the most exhaustive studies on employee satisfaction and business results, it was found that companies with engaged employees outperformed their peers from 2.3 to 3.8 percent per year in long-term stock results. Over the 28 years of data, these companies outperformed their peers from 89 to 184 percent cumulatively (Edmans 2016). The financial and human benefits of adopting an influential leadership style make this a no-brainer on how to lead.

Creating Organizational Success through Influence

Using influence to motivate and impact change is more sustainable than either power or authority. The use of power can be effective for short-term changes, but these changes are not sustainable. Using power to intimidate or get compliance will achieve both, but only for a short time. It is clear that when employees leave companies they are typically leaving their managers. Healthy and high-performing employees will abandon heavy-handed or weak managers, leaving the company with a lower performing employee base. Employees with engaged workforces have an impact on the bottom line.

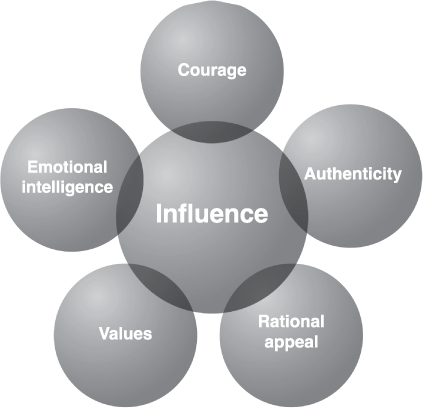

Influence is a multifaceted ability. Our formula for leadership influence is CARVE (Figure 4.1):

Figure 4.1 Formula for influence

Influence = Courage + Authenticity + Rational Appeal + Values + Emotional Intelligence (EQ)

Influence is a combination of deeply understanding oneself, understanding others, developing authenticity, courage, and demonstrating that the values you possess are similar to those held by the people whom you are leading. In order to become a leader with followership, and not simply compliance, mastering these skills is imperative, as we will clarify in the following section.

Leadership Characteristics of Influence: Courage

Effective leadership requires courage. Leaders must have the courage to be wrong or to fail in spite of their apprehensions and insecurities as success without risk is very limited. They must be the flag-bearers for grand ideas and goals yet open to the opinions and ideas of others. Conflict both internal and external to the organization must be embraced, for avoidance of conflict only causes problems to snowball. Too often, courage is associated with analogies about sports or war. These analogies are vivid, easy to understand, and highly limited in scope! Not only are the foxhole and football field venues limited, but the kind of courage demonstrated does not go far. These scenarios often describe courage in the face of physical danger. For the leader, the dangers are equally real. Rather than physical dangers, the leader faces potential damage to the psyche and the ego, which can be just as devastating and long lasting. Being courageous is the cornerstone of having a following and leading through influence.

In most companies, there is a covert recognition of problems that may be holding the company back or impeding growth. Often, those at the very top of the organization fail to see what is obvious to others. This lack of problem acknowledgement by leaders can be the result of a sense of hubris and ownership in having crafted the organization. It can also result from fear of embracing failure or possible challenges previously unrecognized. The failure of the senior management of Kodak to recognize the impact of digital photography is an example. Because of the personal investment in a product or direction, or because of denial, executives often fail to see the obvious. As a result, they stay the course on a path to oblivion. It is the courageous leader who is willing to publicly recognize the obvious, with the understanding that nothing can change that goes unaddressed. It is ironic that simply recognizing the unwelcome obvious can be a statement of courage. Recognizing the obvious raises a leader’s credibility in any organization.

In any organization, there is a tendency toward both groupthink and agreement with those in charge. After all, they are making the big bucks, so they must know better. Being able to take a stand that is different from the group or those in charge, particularly when their idea or initiative has momentum, requires a degree of chutzpah and boldness that is out of the ordinary. This is not to say that being oppositional is a desirable trait. However, being willing to take a position that is at odds with popular opinion and being able to support the position with data is at the heart of being courageous.

One major difference between a courageous stand and one that is born of narcissism and insecurity is that a courageous leader is willing to attack a problem and not attack those who may hold a view that is different. Courageous individuals create a safe environment for others to openly disagree about an issue and not suffer consequences. Being able to brainstorm and have spirited debate is at the heart of identifying solutions and pathways that are of a higher level than routinely following the status quo.

Leadership Characteristics of Influence: Authenticity

In recent years, numerous studies have surfaced on the importance of authentic leadership. Authentic leaders behave in a genuine, sincere manner that is consistent with who they really are. Authentic leaders inspire trust and loyalty among those with whom they work. Research on authentic leadership has determined that it is a strong predictor of employee job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and work happiness (Jensen 2006). Ultimately, authentic leadership is found in three primary characteristics: congruence, humility, and vulnerability.

Congruence has two behaviors that define it. First, it is the requirement that leaders be transparent with their thoughts and feelings and that these match their behaviors. In order for leaders to be considered authentic, they must consistently ensure alignment between what they are actually thinking and feeling and the expression of those thoughts and feelings. This alignment happens both at the workplace and away from it. Congruent leaders are not different in different environments. They are consistently truth tellers who do not present a façade. This alignment requires that leaders have enough self-confidence that their behaviors are not determined by wanting to please or be liked by others. Instead, their behaviors are spontaneously and honestly a response to any situation. The best leaders will always consider their audience and use appropriate tact and diplomacy in delivering their messages without “spinning” them for political correctness or gain. Congruence is developed over time and requires consistency and the ability to be transparent.

Humility is the second quality of authenticity. Humility is the opposite of hubris. It is feeling confident enough not to need to be self-promoting. Humility is the recognition that, although a leader may know most of the answers to any particular subject, no one knows all of the right answers all of the time. Humble leaders recognize that the capabilities and experiences of others can contribute insights and value that they may not have. Humble leaders are open to feedback, open to seriously considering the points of views of others, willing to admit to their shortcomings and to change in the face of new and contradictory information. These leaders are as comfortable making assertions about what they know as they are in admitting when they do not know. They are willing to either share the credit or stand in the shadows altogether. Getting a job done well is more important to the humble leader than the question of who gets the credit. It is the arrogant leaders who believe there is nothing unknown to them and that their views and opinions are of a higher value than those with whom they work. Jim Collins, in his book Good to Great, identified humility as one of the two characteristics leaders of great companies had (the other being fierce resolve). In his study of over 1400 companies, he identified 11 that by his criteria were great. Of the CEOs of these companies, he said that “these good to great leaders never wanted to become larger-than-life heroes. They never aspired to be put on a pedestal or become unreachable icons. They were seemingly ordinary people quietly producing extraordinary results” (Collins 2001). Wow!

Vulnerability, like humility, requires a degree of comfort with oneself that allows others to “look under the hood” regarding their foibles, insecurities, and flaws. According to author and researcher Brene Brown, vulnerability is a combination of uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure (Brown 2012). Vulnerable leaders have a willingness to risk being honest and open about who they are, in spite of judgment or disapproval. Commonly, in competitive work environments there is subtle, but relentless, pressure for leaders to present themselves as “altogether” and without flaws. The truth is we are all flawed. Although everyone knows privately his or her own weaknesses and shortcomings, in public there is pressure to conform to the prevailing cultural expectations of being smart, assertive, capable in all situations, and knowing most, if not all, of the answers. Interestingly, it is the vulnerable leaders that are willing to acknowledge their apprehensions, lack of knowledge, or occasional foibles who have the highest level of respect and trust from their peers and subordinates. The defensive, closed off leader can be intimidating and can get conformity but will not gain a followership of healthy colleagues.

Leadership Characteristics of Influence: Rational Appeal

We always recommend that attempts to influence begin with an appeal to the rational side of those you are hoping to influence. This means beginning with intellectual reason. By initiating presentations and discussions with logic, the leader presents data and the rationale for changes that are being suggested. This concept is especially important for the physician-leader who is often responsible for influencing other physicians and members of the health care team. A phrase commonly heard in the health care setting is “In God we trust, all others bring data.” The rationale must first demonstrate that the proposed change is in the best interest of the patients. Additionally, there should be benefits for the organization, its employees, and the sustaining interests of other stakeholders. If lucid and compelling arguments, grounded in logic and data, cannot be made, there is probably not a good reason to proceed. Always keep in mind that leaders shoulder the heavy responsibility for leading organizations in a manner that benefits multiple constituents. It is a courageous and daunting role!

An example of a rational appeal is that of Satya Nadella’s 2014 reorganization of Microsoft. Microsoft’s culture had become overly competitive, and innovation was diminishing. By sharing with the employees a common goal to reinvent business processes, build the intelligent cloud platform, and create more personal computing, Nadella was able to restructure the organization for the future. Nadella’s restructuring gave employees a new sense that their work had real meaning. It was a bold plan substantiated by equally strong rationale (Troyani 2017).

One challenge relatively unique to the physician-leader centers around evidence-based medicine. In modern health care, evidence-based medicine is the gold standard. There is great confidence in having a double-blind, randomized control study with clear results to support your health care practices. Unfortunately, there is only evidence-based medicine to support about 20 percent of modern health care practice, and most of that evidence is much less powerful than a randomized control trial. To top it off, in many areas of interest, the studies are conflicting in their results, which only further muddies the waters. “Treacherous” best describes these waters for the physician-leader. They must be sure to use evidence-based medicine when the evidence is strong. At the same time, the physician-leader must recognize when the evidence is weak or unsupportive, and an initiative should not be pursued. The most challenging scenario is one that may be the most prevalent. When there is limited evidence or only early acceptance of the evidence, the physician-leader must look beyond the clinical data to determine the value of the initiative. They must take a comprehensive approach that considers both clinical and nonclinical perspectives to craft the best possible rational appeal. Once an initiative is implemented, they must follow the local results and adjust course if indicated. This is one example of where the aforementioned courage comes in handy.

While rational appeal is a tangible and correct place to start the tactical process of influence around any particular initiative or subject, emotional appeal can be equally or more compelling than rational appeal. One thing that differentiates doing work from having a career is the degree to which a person’s efforts relate to the meaning in their lives. This is the emotional side of influence. People want to be a part of a winning team, and they want to be challenged to accomplish great things. They also want to follow a leader they trust and admire. When presented with a goal that connects them to the interests and values of the individual, both productivity and pride increase. The sock company Bombas has the goal of creating a great sock. By itself, that goal does not tug at your heartstrings. However, Bombas has the additional goal of giving one pair of socks to homeless shelters for every pair sold (noting that socks are the number one request from homeless shelters). Now, that is a goal that appeals to the emotions of their workers! As of this writing, they have donated 10 million pairs of socks to homeless shelters. This goal connects the work of their employees to an altruistic and transformational goal. Emotional appeal is multifaceted, but two crucial components of emotional appeal relate to the two leadership characteristics that we discuss next: values and emotional intelligence.

Leadership Characteristics of Influence: Values

One of the most important requirements for effective influencing is the alignment of the values of the leaders and those of whom they are leading. When there is great disparity between the values of the leader and those of his or her constituents, a hurdle arises that they must overcome before they can begin to listen to the leader. In fact, sharing common values with the leader contributes substantially to team members’ trust in a leader (Gillespie and Matt 2004).

Followership requires that followers believe the leader is leading in their best interest as well as the company’s. This comes from the leader knowing those who are being led, demonstrating a degree of empathy and commitment to them, and setting an example they would like to follow. In this era, where there are huge differences between executive compensation and the compensation of those “keeping the lights on,” it is even more crucial for leaders to demonstrate that the values they have are similar to the values of those they are leading. While all promotions into greater leadership positions carry some risk, those leaders who are promoted from inside the organization have a greater chance of success than the ones appointed from the outside. Leaders from the inside are assumed to be made of the same cloth as those with whom they work unless they prove otherwise.

Shared values can exist between a leader and their employees as well as between an organization and its employees. At the organizational level, its values and its proverbial “brand” are one and the same. If the organization’s brand resonates with its employees, this creates powerful influence. Ultimately, if an organization’s staff shares common values with both their leaders and their organization, that is the foundation of a strong culture that will sow the seeds of influence for the leaders within. Creating this sense of common values requires communication from leadership and consistency of actions with words. However, it also requires recruiting and hiring employees who are predisposed to share the organization’s values.

Leadership Characteristics of Influence: Emotional Intelligence

There is a very close relationship between leadership influence and leadership emotional intelligence, or EQ. Emotional intelligence is defined by the degree to which leaders are aware of, and manage, their emotions and the emotions of their fellow employees. Leaders with a high EQ are those who are aware of their own feelings, motivations, and behaviors as well as those of others. They are not only aware of them, but also know how to manage them for optimal results (Figure 4.2). Once again, a very robust relationship between business results and high EQ has been documented in a meta-analysis of 19 studies (Cherniss 2013).

Figure 4.2 A paradigm for emotional intelligence

Source: Goleman (2001).

Not surprisingly, the first condition necessary for leaders to adopt influence as a default leadership style is to have a good understanding of what motivates them. This insight begins with the recognition that all people are flawed, and yet, all people are also exquisitely unique and possess distinct strengths. The acknowledgment of both opposing poles is equally important as together, they form the basis of one’s emotions, and the ability to be intentional about behavior requires a recognition of the underlying emotions in any situation. It is the appropriate management of these emotions that becomes evident in successful leadership behavior.

The great Swiss psychiatrist, Carl Jung, discussed any unawareness we may have as being our shadow side. When we have insecurities and feel anxious in various situations, it is imperative to take ownership of them personally and, as appropriate, publicly. Jung noted that the failure to recognize our shadow side makes us vulnerable to unconsciously “acting out” from it. In other words, when we feel insecure but are either unaware of it or repress it, we are likely to overreact to situations in a fight-or-flight scenario. This is also true when we are unaware, or in denial, about the strengths we have. We will likely underutilize our strengths and be plagued with unnecessarily low self-esteem, not recognizing the uniqueness we can bring to any situation and lacking the courage to assert ourselves.

The second part of the EQ equation is understanding and managing the feelings of others. This can be trickier and not only involves a desire to comprehend individual uniqueness but also requires the intentionality to recognize the emotional behaviors of others and act on their behalf. Having empathy and understanding how others are motivated can result in productivity, followership, and engagement. Even more difficult is understanding the psychological foundations of others and how that manifests in the form of day-to-day behavior. That is ultimately the challenge for all leaders as this understanding is necessary for them to succeed in their duty to provide emotional and psychological support to their employees. True success in this regard provides an incredible source of emotional appeal and influence for the leader.

Case Study

Being Right or Being Successful?

A small, growing hospital called us about assisting in the onboarding of a new chief medical officer (CMO) whom they had just promoted. Their prior CMO had recently retired, and the CEO was intent on promoting from within. As the CEO reviewed internal candidates for the position, she decided to take a chance on a young, up and coming physician who was a very good surgeon but had little management experience. The surgeon had been very successful in the surgery theater, where he was known as someone who was very insightful, confident, and skillful. In addition, he had the reputation of being direct, authoritative, and tolerating no nonsense. The CEO believed that these were the very skills needed in the CMO position, in which the retiring CMO, who lacked them, had been less than effective.

Shortly after being promoted into the CMO position, the CEO began hearing complaints from other physicians about the heavy-handed nature of the new, energetic CMO whom she had promoted. The concerns were all of a similar nature: the CMO was being authoritarian, not listening well to the ideas of others, abrasive in delivery, very certain in his point of view. When the CEO confronted the new CMO with these concerns, the CMO initially got defensive, noting that the CEO had said she wanted changes to be made. The CEO countered that it was not the what of his approach but the how. With this realization, they both agreed that, in order for the new CMO to be effective, some leadership coaching could be of great help. At that point, we were engaged to assist.

In our initial interview with the CMO, we discussed what had made him successful as a surgeon. In the surgery theater, he had been the central authority in the room. He was the leader, the authority, and the choreographer. In that role, he had to make quick decisions, be very directive, and leave little room for discussion or ambiguity. He was a machine! He wrongly believed that by having the title of CMO with the commensurate authority, people would respond much as they had in the operating room. He was perplexed that when applying the same behaviors that had made him successful in surgery to his new role, he was not getting the same results. However, he could see clearly that he had to make some changes in order to be successful in the CMO position.

Over time and through a process of coaching and administering a 360-degree assessment, we helped him understand that the kind of behaviors necessary for exercising leadership were quite different from those for being a top-notch surgeon. His high conscientiousness (and perfectionism) with his low agreeableness worked well in the operating room but not as well in managing his team. Being an effective leader requires listening to those whom you manage and support. Collaboration, negotiation, interpersonal sensitivity, dialogue, and, most importantly, patience are essential behaviors for becoming an effective leader. Except for patience and dialogue in some circumstances, these behaviors would have all interfered with performing successful surgery. Because he was motivated to succeed and willing to listen and change his behavior, he became a very effective CMO. The transition was not without some pain, repairing relationships, and “eating some crow,” but the CMO was ultimately able to make the transition from being a very successful surgeon to being a successful physician-leader.

Influence and the Implications for the Physician-Leader

Creating influence is the essence of leadership for any leader. The power derived from title and authority is at best marginally effective and can only be used sparingly. Long-term, sustained, and successful leadership is born only out of the amorphous skill we call influence. Although this chapter addresses influence primarily with regard to a leader’s employees, influence is also of paramount importance with peers and even superiors. The tactics of influence hold true regardless of the subject group. Few other types of leader rely on influence as much as the physician-leader. Often caught between the worlds of the clinician and the administrator, the physician-leader frequently carries little to no authority in either realm. To their physician colleagues, these leaders will always be peers to a large extent. To their administrative colleagues, these leaders are often viewed, at least partially, as outsiders. To be successful, physician-leaders must master the art of influence.

There are a couple of potential challenges to creating influence that all physician-leaders should be aware of. As we discussed in Chapter 3, physicians as a profession exhibit some common psychological traits. Low neuroticism (high emotional stability) is common to many physicians. This can be a hindrance in creating influence as it can impair authenticity and vulnerability, making the physician less relatable to others. Intentionality in the areas of congruence and vulnerability can help mitigate this for many physician-leaders. We have also discussed that agreeableness tends to vary in physicians by specialty. It is important for physician-leaders to have an accurate assessment of their agreeableness. Focus should be directed toward finding the proper balance in this area to create influence. Physician-leaders who are low in agreeableness tend to struggle with creating influence, whereas physician-leaders who are too high in agreeableness tend to struggle with using their influence. In fact, it is a common mistake among new physician-leaders to default to acting as a mediator among other physicians, describing the landscape and helping the group come to consensus. While this may not seem like the worst thing in the world, a leader is not merely a mediator. A leader, by role, is supposed to be more informed and have more ability and time to analyze any given topic. The physician-leader must be more than a mediator. They must develop and wield influence so that they can guide the group and organization to a successful outcome. Influence for them includes developing respect for their expertise and opinion so that they are true leaders and not merely facilitators.

Finally, you will recall that, contrary to the leadership arena, the clinical arena is one that is predicated on the authority of the physician. The clinical physician conducts their job using orders, and they are the ultimate clinical authority. Creating influence is a paradigm shift for many physicians moving into leadership roles for precisely this reason. Awareness of this fact and attention to the tactics discussed in this chapter can help them overcome this barrier.

Coach’s Corner

Influence is the primary virtue and engine of leadership, not authority. Rank and title do not confer lasting leverage. There are many aspects that contribute to creating influence and followership. The successful leader will develop and employ the foundational skills detailed in this chapter to create influence, manage change, and drive results in their organizations.

- •Consider when and how authority can be used to lead. Identify the present and future challenges created by using authority to accomplish change. Continue this exercise until you are convinced that leading through only authority is unsustainable at best and ineffective at worst.

- 2.Determine your ideal leadership style

- •Using the CARVE model presented in this chapter, reflect on the strengths and opportunities in your personal leadership style. The best leaders develop their own unique style that encompasses foundational leadership skills while embracing their own personality.

- 3.Be patient

- •Very few great leaders are born that way, and creating influence takes time. Consider this endeavor the core work of leadership. Give it your constant effort and attention, but be patient. The progress can be imperceptible at times, but the end result is monumental.

Beard, M., and A. Weiss. 2017. The DNA of Leadership: Creating Healthy Leaders and Vibrant Organizations. New York, NY: Business Expert Press.

Brown, B. 2012. Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent and Lead. New York, NY: Avery.

Cherniss, C. April, 2013. “The Business Case for Emotional Intelligence.” Consortium for Research on Emotional Intelligence in Organizations. Yale University. http://www.eiconsortium.org/reports/business_case_for_ei.html (accessed November 19, 2018).

Collins, J. 2001. Good to Great. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishers.

Edmans, A. March, 2016. “28 Years of Stock Market Data Shows a Link between Employee Satisfaction and Long-Term Value.” Harvard Business Review, Organizational Culture. https://hbr.org/2016/03/28-years-of-stock-market-data-shows-a-link-between-employee-satisfaction-and-long-term-value (accessed November 19, 2018).

Garrett, A. January, 2017. “Summa CEO Thomas Malone Resigns: What Happens Next at Summa Remains Unclear.” Akron Beacon Journal. https://www.ohio.com/akron/writers/betty-linfisher/summa-ceo-thomas-malone-resigns-what-happens-next-at-summa-remains-unclear (accessed November 17, 2018).

Gillespie, N.A., and L. Matt. 2004. “Transformational Leadership and Shared Values: The Building Blocks of Trust.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 19, no. 6, pp. 588–607. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940410551507 (accessed November 20, 2018).

Goleman, D. 2001. “An EI-Based Theory of Performance.” In The Emotionally Intelligent Workplace, eds. C. Cherniss and D. Goleman. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Gooch, K. August, 2016. “Southern Coos Hospital CEO Terminated.” Becker’s Hospital Review. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-executive-moves/southern-coos-hospital-ceo-terminated.html (accessed November 17, 2018).

Jensen, S.M. December, 2006. “Entrepreneurs as Authentic Leaders: Impact on Employees’ Attitudes.” Leadership & Organization Development Journal 27, no. 8, pp. 646–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730610709273 (accessed November 20, 2018).

Losey, S. October, 2017. “Air Force Medical Squadron Commander Fired, under Investigation.” Air Force Times. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-air-force/2017/10/16/air-force-medical-squadron-commander-fired-under-investigation (accessed November 17, 2018).

Roth, T., and B. Conchie. 2008. Strengths Based Leadership: Great Leaders, Teams, and Why People Follow. New York, NY: Gallup Press.

Sinek, S. 2009. Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action. New York, NY: Portfolio Books.

The Lowell Sun. March, 2018. “Renowned Trauma Center Fires Its Medical Director.” March 8, 2018. The Lowell Sun. http://www.lowellsun.com/breakingnews/ci_31720242/renowned-trauma-center-fires-its-medical-director (accessed November 17, 2018).

Troyani, L. May, 2017. “3 Examples of Organizational Change Done Right.” Tiny Pulse. https://www.tinypulse.com/blog/3-examples-of-organizational-change-and-why-they-got-it-right (accessed November 20, 2018).

Wells, J. March, 2018. “Court Documents Shine New Light on Hospital, CEO Dispute.” Vineyard Gazette. https://vineyardgazette.com/news/2018/03/15/court-documents-shine-new-light-hospital-ceo-dispute (accessed November 17, 2018).