Delegation: Maximizing Leadership Impact

In clinical practice, the wise and efficient physician delegates many duties to nurses, medical assistants, and other staff because of time constraints. Obviously, physicians cannot do everything for their patients, nor is it desirable. Because the current primary care system is inefficient and overstretched, primary care physicians, sometimes seeing over 40 patients per day, are hard-pressed to handle patients’ needs without cutting corners (Lichtenstein et al. 2015). This stretching of physicians to do more and more is a major contributor to the 46 percent of physicians suffering from burnout (Schattner 2012). Whether by design, or out of necessity, physicians have learned how to delegate in clinical settings. They perform better and enjoy the work more.

An important distinction of typical clinical delegation is that it often does not entail true delegation of responsibility and decision making. When delegating to nurses and medical assistants, the tasks being delegated are often important but do not require high-level decision making. An example of this is medication administration. In contrast, delegation to an advanced practice provider does involve transferring some responsibility and decision making. Research on geriatric patient care has determined that delegation to nonphysician providers is associated with a higher quality of care for geriatric conditions in community practices (Abrams 2013). Indeed, some physicians have become partially or totally comfortable delegating decision making to advanced practice providers, but many physicians still struggle with giving up control and responsibility. Effective delegation for physician-leaders requires embracing this next level of delegation.

Compared with its significance in a clinical role, delegation in a leadership role is equally critical, in a slightly different way. In a clinical setting, many tasks are delegated because there is more work to do than time or resources allow. The same holds true in physician-leadership roles. However, there are clearly differences because of the primary focus for physician-leaders. Although patient care or quality may be behind the need to delegate, for the physician-leader this relationship is a much more distant one, often with several layers between the physician and the patient. In physician-leadership roles, the focus is on the function, service line, or organization. The higher the physician-leader rises in the organization, the more the focus will shift from frontline operations to system operations, policy, and strategy. Clearly, patient safety and quality can still be the areas of focus, but at the system or policy level rather than at the individual patient level.

In leadership roles, the physician is often working with nonphysicians and even nonclinicians. In fact, many health care leadership roles at the administrative levels involve mostly nonclinicians (e.g., finance, information technology, medical records, facilities, marketing). The physician-leader may be a part of an interdisciplinary team or leading one. When leading the team, the physician-leader may have some choice as to the talent and skills that are on the team. Unlike the clinical setting, the roles on the team are more varied and have greater specialization of skills.

Why Delegate?

The most obvious question to be answered by physician-leaders is, why delegate those things that the physician-leaders may be qualified to do themselves and may even do better? The obvious answer is limited bandwidth. It has been said that “you can do anything, but not everything.” It is important to do that which is of high priority and not try to do all there is to do. Stephen Covey noted that the urgent can often undermine the important. One of the early lessons physician-leaders must learn is that in order to accomplish the goals of the larger organization, there is more work to be done than any one person can, or should, do. In addition, there are skills and capabilities that others possess that may be better suited for some of the work. We have identified four major reasons the physician-leader must learn to delegate.

- 1.Productivity: Any health care organization has multiple initiatives going on simultaneously. The organization functions like one big flywheel, always moving and waiting for no one. The most effective organizations recognize that it requires a team to undertake all of the work in order to get ahead of, or even keep up with, the demands of multiple constituents. The most effective physician-leaders understand the necessity of delegating. At its core, delegation makes possible getting more work accomplished through others than any one person could manage alone in the time allotted. As measured by volume of work, productivity is one measure of a high-performing organization.

- 2.Impact: In order to deliver the highest value contribution, physician-leaders need to focus on those issues that are the most important, not just the most urgent. Effective delegation is about maximizing impact. This requires physician-leaders to differentiate the work they should do from what should be delegated. It also requires them to be selective with regard to whom work is delegated. The most important work with the highest impact should be undertaken by either the physician-leader themselves or someone who has a full grasp of the items being delegated. The concept of maximizing impact is often referred to in the clinical setting as having staff work at the top of their license. In other words, each person must focus on activities at the high end of what their training or license allows, avoiding the busy work that a lesser trained individual could accomplish. We have referred to the physician-leader in many ways as the conductor of an orchestra. Although the conductor may have once been a violinist or other musician, the most beautiful music is created only if the conductor focuses on leading and coordinating the various musicians as opposed to stepping in and playing the violin. Thus is the challenge for physician-leaders.

- 3.Development: The growth and development of the leader’s staff is always a high priority for an effective leader. The best physician-leaders regularly look for opportunities to increase both the depth and the breadth of their subordinates for succession planning and increasing organizational effectiveness. Sending staff to workshops and additional education are ways of increasing staff capabilities. However, on-the-job development is more directly related to the organization and is practical and cost-effective as a way to develop staff. Providing growth opportunities through delegation of stretch assignments gives staff members the opportunity to increase their capabilities under the supervision of a supportive manager. Being supportive means, at least in part, both accepting and tolerating failure. Stretch assignments are meant to expand the limits of staff capability. Despite appropriate oversight, errors will occur. The best learning will result from these failures. The key for the leader is to avoid the so-called fatal errors and provide positive reinforcement for staff when they do fail as long as they are not committing the same mistakes repeatedly.

- 4.Creating Brain Space: Finally, the physician-leader is freeing up time for thinking about higher-order issues by delegating effectively. Such issues may include organizational planning, talent development, innovation, trends in health care, policy reviews, or a host of any other items that have a broad impact on the organization and warrant time to consider, study, and plan. When the physician-leader stays mired in details that others could handle, there is no time to meet the expectations that led to the physician-leader being promoted into the role. This concept is an underappreciated core component of leadership. Strategy development and leading, in general, requires thought, not just action. Too many leaders fail to create the brain space necessary to think and thereby improve both themselves and their organizations.

Case Study

Assign or Perish

The Chair of the Pediatric Department of a large academic medical center was balancing clinical practice with the demands of chair responsibilities. New in her role, she complained about not having enough hours in the day to get all of her work completed. She found herself arriving each morning before the other physicians arrived and leaving in the evening after all other staff had been long gone. In addition, she realized she had begun coming in on Saturdays to get paperwork completed and even answering e-mails from home on Sundays. When she had accepted the position, she had done so with much enthusiasm and had great plans for improvements that could be made to patient care, education, and research. Now, 6 months into the role, she was considering whether she should return exclusively to clinical practice. She had that conversation with her boss, the Dean of the School of Medicine, letting him know of her dilemma. The Dean suggested that working with an executive coach might help her sort through the issues and provide her with alternatives that could make her schedule more balanced and her workload more tolerable.

When we met with the new physician-leader, we were impressed with her passion, her vision, and her level of engagement. We were also aware that she was fatigued and on the front end of feeling defeated because of the load she was carrying. As a first step, we conducted, with her encouragement, a full personality evaluation to determine whether any personality dynamics could be impacting her work style.

The results of the evaluation were striking. Like most pediatricians, she had a high level of agreeableness. She clearly valued relationships and regularly put relationship development above task accomplishment. She was compassionate, cooperative, and inclusive. She also had an exceedingly high level of conscientiousness. She was highly disciplined, detail oriented, and highly organized. She was a perfectionist on steroids. This combination of having a high sensitivity to the demands she might ask of others with her strong penchant for having everything done as flawlessly as possible resulted in her sense of great pressure to do everything herself, rather than delegate any tasks.

She was missing two key requisites for becoming an effective physician-leader: differentiating between what is truly important from what seems urgent but is not very important and relying on her team to help her through effective delegation. We began helping her develop a process by which all of the many tasks she had could be triaged into one of three categories: tasks that must be done now, tasks that can wait until later, and tasks that do not need to be done at all. We further helped her recognize that, in order to succeed, she would have to trust her staff and be willing to delegate a substantial amount of her work. We helped her see that her perfectionism had more to do with the unrealistic expectations she had of herself than the degree to which tasks needed to be done flawlessly or immediately. She readily embraced our counsel and began to triage and delegate. Her new approach proceeded by fits and starts, but she was persistent. We checked back with her in 3 months and found a new person. Her ability to let go of her perfectionism and trust others to help her had paid massive dividends. She was again able to enjoy her clinical practice along with her administrative duties. She was working reasonable hours and had stopped coming in every weekend. Ultimately, she was pleased that she had taken on the role and was beginning to see good progress on the problems she had sought to improve.

Why Delegating Is Difficult: Understanding Your Delegation Style

In spite of physician-leaders grasping the importance of delegation, we have identified some prevalent management styles that can undermine effective delegation. Even with the physician-leaders’ best intentions, their preexisting personality and relationship formation impact their delegation style. We have identified three dysfunctional delegation styles.

The Micromanager: A physician’s training requires high levels of attention to detail and the assumption of full responsibility for patient outcomes. Conscientiousness and micromanaging can go hand in hand. The micromanaging physician-leader may delegate but continue to hover, push, redo work, and make the life of their staff very difficult. This occurs because of the following:

- •Trust: Physician-leaders may not trust those to whom they are delegating. This typically is more about the physician-leader being concerned about outcomes than about the capabilities of the individuals to whom they are delegating. It is also related to the physician being required to manage all aspects of patient care in the clinical arena. This same sense of responsibility can interfere with trusting others to complete assignments. When physician-leaders do not trust the staff to complete delegated work, they need to ask themselves one of three questions:

- 1.Do they have the right people under them? If not, should they restructure to get the right people in the right positions?

- 2.Do the people under them have the right skill set? If not, do they need to provide them with additional training to be effective?

- 3.Do they need to grow in their intrinsic ability to trust? If so, they may need to ask themselves what is behind their difficulty in trusting.

No one likes to have someone constantly looking over his or her shoulders and managing every step. It is toxic for the morale and for productivity. Distrusting your staff will lead to good people leaving.

- •Control: Equally destructive effects of having a lack of trust flow from the physician-leader who must control all aspects of what is delegated. This is another holdover from clinical practice in which many physicians feel the need to be in full control of patient treatment. By keeping all aspects of a patient’s care under his or her control, the physician can take greater comfort in a positive outcome. As a physician-leader, this same level of managing all aspects of what is delegated is ineffective, at best, and detrimental to both staff and ultimate outcomes, at worst. Similar to the clinical setting, another peril that physician-leaders face in this arena is maintaining control by only delegating transactional tasks as opposed to more complex projects that require some delegation of authority and decision making. Inability to delegate the latter will result in suboptimal organizational performance.

- •Perfectionism: Physician mistakes in clinical practice can have dire consequences, including bad patient outcomes, medical liability, or even loss of the physician’s license. In perhaps no other profession is the focus on “measuring twice and cutting once” more prevalent than in the medical profession. As a result, physicians become perfectionists, if they are not already predisposed. The same perfectionism is rarely required in the world of organizational life, and it can even interfere with productivity, impact, and morale. It becomes important for the physician-leader to spend time differentiating between those rare issues that require a high level of perfection and those that do not. Being perfectionistic on all matters results in analysis paralysis and can bring the organization to a halt. Although it is important to have standards for what is delegated, the physician-leader needs to be realistic in his or her demands, balancing the quality of work with the outcomes needed.

The Abdicator: It is very common in leadership practice to hear about the importance of “empowering” others to do the work they have been assigned. The principle behind empowerment is that people need to have authority commensurate with responsibility. In other words, when people are delegated work and given guidelines on the level of quality and time lines needed, they should be able to get the work completed in a manner consistent with their particular work style. However, for some leaders, empowerment means throwing work “over the fence” and not being involved in any subsequent measure. In short, their style is benign neglect. The new physician-leader, often unaccustomed to delegating in an administrative sphere, can inadvertently abdicate. This is often because of a lack of management training and/or not having a process in place. Interestingly, benign-neglect leaders are often the ones that talk about their “great staff,” primarily because they do not have to do much work! Being an absent leader is every bit as harmful as being one that is overinvolved. It impacts staff morale and erodes the leader’s credibility. We have identified three primary reasons for this abdication of responsibility.

- •Overbooked: In particular, new physician-leaders often have difficulty declining requests for meetings, assignments, or involvement on committees. They may not have the experience to differentiate between those requests to which they should commit and those they could deal with by delegating or not accepting altogether. As a result, their full schedule interferes with the oversight of delegated assignments. Learning how to say “no” appropriately is a skill most leaders must learn early in their careers.

- •Fear of interfering: Physician-leaders are not exempt from wanting to be liked. In fact, being liked, alongside with being respected, are good leadership foundations. However, when their need to be liked keeps them from getting involved for fear of hurting feelings or being seen as overmanaging, it will cause problems with both productivity and morale. Ultimately, it is a failure to create healthy boundaries when the physician-leader wants to be more of a friend than a manager. Such leaders lose the respect of their staff. Strong people want ongoing involvement with their leader and consider it a vote of confidence. On the other hand, inattentive leaders create weaker staff.

- •Inattention to detail: Periodically (although likely rare as physicians are known to be high in conscientiousness), it is the case that the physician-leader is highly conceptual and not detail oriented. These leaders are more likely to see the big picture and look at systems rather than focus on tactics. Once they have a broad understanding of a problem or issue, they can become bored with implementation. Work coming from these physician-leaders may be more strategic but is less likely to be flush with details. This approach can work when the physician-leader is surrounded by detail-oriented, self-managing staff. However, if the final product is not scrutinized after it is delegated, there may be organizational consequences that are unpleasant.

The Waffler: This delegation style is characterized by the physician-leader regularly changing directions, baffling staff, and creating havoc. In one privately held organization with which we consult, the CEO/founder will reach agreement with his staff on a particular direction or set of objectives on which to focus their work. The staff will begin working on the objectives outlined by the CEO. The staff will hold subsequent update meetings, engage vendors, and begin making decisions. However, not uncommonly, the CEO, who is often taking time off, will helicopter back in to let the staff know either that he has changed his mind on the subject or that their work is substandard and he wants to go in a different direction. Needless to say, this undermines the staff and undercuts their authority to make decisions. Morale is always low, and staff have learned not to begin working on something until the CEO has mentioned several times that he wants to go in a particular direction without wavering. Talk about a loss of productivity!

These delegators tend to be plagued by insecurity. They are constantly questioning their own decisions and regularly rethinking decisions they have previously made. In addition, they are often characterized by the “shiny new object” syndrome, in which they are always believing that a better idea is “out there.” As a result, they have difficulty committing to a course of action. They can also be victims of the “last-in” syndrome. Similar to attraction to the “shiny new object,” the leader will gravitate to the opinions of the last individual to whom they spoke (usually outside the company) and make decisions based on that conversation. Obviously, this is a vicious cycle because there is always the next “last-in” person’s opinion to consider. Of the three dysfunctional delegators, the helicopter is the least predictable and most destructive. Such unpredictability keeps staff constantly off balance and on edge.

Regardless of what kind of dysfunctional delegation is represented, such physician-leaders seriously suboptimize their staff. They also risk either slowing down progress (as in the case of the micromanager), producing lower quality results (the abdicator), or frustrating their organizations while both slowing down progress and producing suboptimal results (the waffler). Learning to become an effective delegator is a companion skill to creating a vision (Chapter 5) and developing a high-performing team (Chapter 6).

Effective Delegation: Creating a Process

The biggest challenges of new physician-leaders are to: (1) differentiate issues with regard to complexity and impact; (2) understand the capabilities of their staff; (3) put a process in place to delegate effectively; (4) create accountability. We have found that having a process not only ensures that work gets done, but that the physician-leader is focusing time and effort on the right kind of issues and has a rationale for those things that are delegated. Keep in mind that advantages to effective delegation include creating both great outcomes and brain space for the physician-leader. Effective delegation is systematic and stepwise, providing the mechanism by which the physician-leader can effectively manage the organization.

Differentiating issues by establishing beachheads: Not all issues are alike. In the course of a day, week, or month, numerous requests cross the desk of physician-leaders. New physician-leaders tend to say “yes” too often because they do not have the experience to effectively determine those requests in which they should be involved, those they can delegate, or those that do not need to be dealt with at all. This process is simply another application of the skill of triage, with which physicians are already adept.

Early in their positions, physician-leaders need to establish beachheads pertaining to their, and their team’s, availability to be involved in organizational initiatives. These beachheads are the parameters defining the kinds of initiatives in which they will, and will not, be involved. It is important to broadcast these parameters to the organization. An enormous amount of time is wasted in organizational meetings that are often unnecessary, involve people not directly related to the issue, and do not have an agenda or a plan. In a survey of 182 executives, researchers found that executives spend an average of nearly 23 hours per week in meetings. Here are some staggering statistics about the impact of meetings and e-mails on the time of organization leaders (Chignell 2019; Perlow, Hadley, and Eun 2017).

- •65 percent of managers believe meetings keep them from completing their own work

- •71 percent believe meetings are unproductive and inefficient

- •64 percent said that meetings come at the expense of deep thinking

- •62 percent said meetings miss opportunities to bring the team closer together

- •Dysfunctional meeting behaviors have been associated with lower levels of market share, innovation, and employment stability

- •A typical corporate employee receives about 110 e-mail messages daily

- •The average number of legitimate corporate e-mails received daily is 62

- •Of the legitimate e-mails, only a small number are directly related to the receiver

These statistics point to the alarming truth that an incredible amount of time and productivity is lost sitting in meetings that are poorly conceived, have the wrong invitees, and are poorly run, resulting in equally poor outcomes. More time is lost in reading and responding to unnecessary e-mails. Thus, when considering all of the requests that will be made of physician-leaders, they need to make certain that each one really needs attention from them or their staff and justifies the expenditure of time and energy required. Surprisingly, this is the first prerequisite in creating a delegation process. The less physician-leaders have to do or delegate, the more time there is available for them and their staffs to work on more important issues. In this respect, physician-leaders become the gatekeepers for their areas of responsibility.

Gatekeeping: Assuming the request of the physician-leader crosses the threshold of being warranted, requests typically fall into four categories. We have found that the importance and uniqueness of the request assists physician-leaders in determining whether or not the request actually needs their attention.

- •Information: These requests are usually information-only requests. As such, they are simple and do not require much time or energy on the part of the recipient. Unless the information is confidential or known only to the physician-leader, it can usually be delegated. In the event that you, or your staff, are on a large distribution list for communication, request the senders to delete you from the list unless you have something specific to contribute.

- •Involvement: With involvement, the expertise or wise counsel of the physician-leader or their subordinates is being requested in the form of being involved on a standing committee or task force. Caution! When there is a request for you, or your staff, to be on a committee or task force, resist the urge if possible. Unless truly warranted, these are incredibly low-productivity time killers. At the least, request an agenda to review before accepting any invitations.

- •Problem-solving: Almost universally, these requests need to have the attention of the physician-leaders or their staffs. However, as noted previously, ensure that you are not simply part of a distribution list and that there is specificity with regard to the request.

- •Crisis: Typically, the physician-leader needs to be involved in these requests. They are very specific and short term. The role of the physician-leader is very clear. Requests of this sort often come from senior leaders in the organization, and participation is expected.

Understanding Talent: Matching Requests with Capabilities

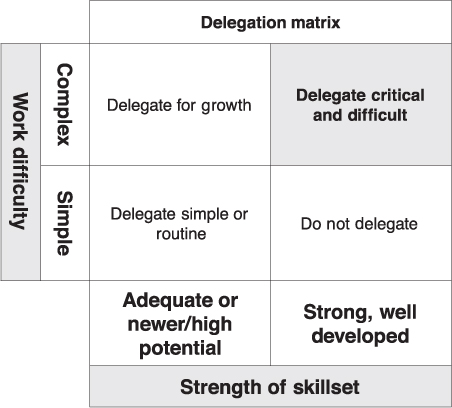

Once requests have been appropriately sorted and the physician-leader has determined which of the requests can be delegated (versus doing or discarding), the next step is to determine to whom the request/work should be delegated. The gating process needs to include how complex the work is, the impact of the work, and the urgency of the request. These are prerequisites in determining to whom the work should go. On any staff, leaders typically have a “go-to” person—that person who is consistently reliable, gets work completed at a high level and in a timely manner. That is the good news. The downside to delegating to the go-to person is that he or she becomes inundated with requests, and the workload in the organization becomes skewed, with less reliable or lesser known staff doing less work. Conducting a review of the capabilities of the staff to consider to whom requests should be given saves time and increases productivity. In addition, when reflecting on developing staff, it is often the case that you will want to delegate stretch assignments to them, in order to help them in their professional growth. We have found that having a delegation matrix (Figure 7.1) can be helpful to determine to whom you want to delegate (Beard and Weiss 2017).

Figure 7.1 Delegation matrix

Source: Beard and Weiss (2017).

In this matrix, the leader classifies the staff according to the strength of their skill set. Work requests are classified according to the difficulty or criticality. The intersection of these variables determines to whom requests are delegated. In this respect, delegation becomes intentional rather than haphazard. The process ensures that the work will be undertaken by those with capabilities commensurate with the request. It also ensures that the work will be completed at a level that satisfies the request. This process is a tool for physician-leaders to multiply their impact in the organization, rather than simply being productive.

Delegation Tools for Results

At this point, the physician-leader has vetted the request, identified to whom the request should be assigned, and made the assignment. All done, right? Well, not quite done yet. Being intentional about vetting and assigning are necessary preconditions for success. Now the work begins. Being clear about expectations for outcomes is equally important. The Levinson Institute has created a simple, but powerful, way to think about delegation expectations. It believes that accountability must be clearly defined and has developed a formula for accountability (Kraines 2001):

Accountability = Q + Q + T/R

In this formula, Accountability is the sum total of quality, quantity, timeliness, and the resources required to complete the assignment. Accountability is the responsibility of individuals to complete the tasks they are assigned in a timely manner and with the expected results. This definition requires two predetermined practices. First, individuals must be given clarity with regard to the expectations they are expected to meet. Second, individuals must be given the authority commensurate with the responsibilities they have been assigned. Using this approach provides the specifics with regard to the physician-leader’s expectations for the work being assigned. This provides a scorecard of sorts for evaluating the completeness of the final work product.

Quality: This relates to both fully completing the work and maximizing the intended impact of the results. Quality always includes significant attention to detail, correctness, accuracy, and excellence in the final product. Producing a high-quality work product also includes seeking the input of other experts, ensuring that the work follows well-established workplace principles, and identifying all of the needs that must be satisfied in completing the task. Questions to ask include the following: (1) Have the right people been included in the final review? (2) Does everyone have the information required to make decisions about the outcome? (3) Has a venue been established for reviewing and presenting the work? (4) Have adequate communication channels been established to communicate about work products to selected audiences? Missing any one of these characteristics suboptimizes the final work product.

Quantity: As it would seem to imply, quantity is how much, or how many, of the final products are required in order to consider the assignment completed. Quantity is also the degree to which the completion of a task fulfills its intent. Does completing 50 percent of the paperwork fulfill the expectation of task accomplishment? By checking half of the patients on rounds will the clinician have satisfied the requirement for managing patient quality or safety? When work is assigned, built into the front end of the task should be clear specifications with regard to the amount or degree of task completion that satisfies the intent of the assignment. It cannot be assumed that individuals to whom tasks are assigned will automatically know exactly what is required for successful task completion.

Timeliness: Establishing dates and times for reviewing milestones of the work process needs to be done up front. Creating and scheduling a cadence of review updates is required. Another up-front requirement is determining if there are intermediate milestones that must be met and what conditions require escalation for reviewing problems. Also, a date for the final presentation of the work product must be established.

Resources: Physician-leaders are responsible for ensuring that those to whom they have delegated the work have the resources to get the work completed in a satisfactory manner. This usually involves a discussion between the physician-leader and the staff person to whom the work has been assigned. It makes little sense to assign an important initiative and handcuff the individual doing the work because the right resources have not been identified and allocated. Resources include financial as well as human resources. If applicable, has a budget been established for completion of the project or product? It is important to pinpoint other organizational functions that will be impacted in the accomplishment of the task and other people that will need to be notified to secure their support.

Incentives: Most delegated assignments are part of the day-to-day work and a routine part of the job. However, there are assignments that are so large, important, or long-lasting that when they are assigned, there is a carrot offered to be received at the completion of the assignment. An example of such a situation would be that of offering a carrot for taking the assignment to be on a merger integration team for a newly acquired company. This merger integration work would be done in addition to their “day job.” As such, the individual conducting the work will be involved at nights and on weekends for a period of time until the integration is completed. A financial reward or promotional assignment may be the carrot at the end of the project. Typically, these kinds of rewards are for assignments that go above and beyond the individual’s routine work and temporarily extend his/her job description considerably, on behalf of helping the company.

These delegation tools are effective only inasmuch as they are adhered to by the manager. It is our experience that when projects fail, it is usually the result of poor up-front delegation requirements being established (QQT/R) and poor follow-up. The discipline of incorporating this process into delegation will better ensure that work will be accomplished as intended.

What You Can Never Delegate

There are some things physician-leaders can never delegate, particularly as they move into administrative roles. These are items or issues that have some level of confidentiality associated with them. The higher physician-leaders rise in an organization, the more they are privy to information that is not available to the overall organization. Typically, the dissemination of this information requires discretion.

Confidential workplace information usually falls into one of three areas: employee information, management information, and business information (Halpern 2015).

- •Employee information includes confidentiality associated with the sharing of personal identifiers. In addition, employees’ medical and disability information must be kept confidential and has limited access on a “need-to-know” basis.

- •Management information includes information related to employee relations issues: disciplinary actions, impending layoffs, terminations, and workplace investigations.

- •Business information refers to “proprietary information” or “trade secrets.” This is information not generally known to the public or available to competitors. Business information can also include pending acquisitions or the launch of new products and services.

Using confidential information indiscriminately or leaking it, inadvertently or otherwise, can be a disciplinary matter and have serious consequences, including loss of position or personal liability exposure. Similar to doctor–patient confidentiality, confidentiality at the organizational level can be breached only when it is determined that significant harm may result if the information is not disclosed to the right person. There is typically a very narrow interpretation of when a breach is justified and on whose authority the interpretation rests. It is always better to be conservative in dealing with such issues.

Coach’s Corner

Leadership is achieving results through others. Strong leadership requires aligning the efforts of others so that the product is not simply additive but synergistic. Effective delegation is not simply tasking others with work. The delegation process and tactics outlined in this chapter provide the foundation of strong leadership.

- 1.Identify your delegation style

- •Reflect on your personal delegation style. Do you suffer from characteristics of the Micromanager, the Abdicator, or the Waffler? Identify specific actions you can take to improve your delegation style.

- 2.Focus on your delegation process

- •Apply the delegation matrix and its prerequisites to your delegation process. Create an action plan to develop the process components that you are not currently employing effectively.

Abrams, L. February, 2013. “To Love Medicine Again, Physicians Need to Delegate.” Health. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/02/to-love-medicine-again-physicians-need-to-delegate/272782 (accessed January 21, 2019)

Beard, M., and A. Weiss, A. 2017. The DNA of Leadership: Creating Healthy Leaders and Vibrant Organizations. New York, NY: Business Expert Press.

Chignell, B. January, 2019. “How to Manage Email Overload at Work.” CIPHR. https://www.ciphr.com/advice/email-overload/ (accessed May 2, 2019).

Halpern, J. October, 2015. “Why Is Confidentiality Important?” Jules Halpern Associates LLC News and Articles. https://www.halpernadvisors.com/category/restrictive-covenants (accessed January 24, 2019).

Kraines, G. 2001. Accountability Leadership: How to Strengthen Productivity through Sound Managerial Leadership. Pompton Plaines, NJ: The Career Press.

Lichtenstein, B.J., D.B. Reuben, A.S. Karlamangla, W. Han, C.P. Roth, N.S. Wenger. October, 2015. “The Effect of Physician Delegation to Other Health Care Providers on the Quality of Care for Geriatric Conditions.” Journal of the American Geriatric Society 63, no. 10, pp. 2164–170. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4762652 (accessed January 21, 2019).

Perlow, L., C.N. Hadley, and E. Eun. July–August, 2017. “Stop the Meeting Madness.” Harvard Business Review, pp. 62–69. https://hbr.org/2017/07/stop-the-meeting-madness (accessed May 2, 2019).

Schattner, E. August, 2012. “The Physician Burnout Epidemic: What It Means for Patients and Reform.” Health. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2012/08/the-physician-burnout-epidemic-what-it-means-for-patients-and-reform/261418 (accessed January 21, 2019).