8 Multicultural Teams

8.0 Statement of the problem

A failed teamwork project

In attempting to plan a new project, a three-person team composed of managers from Britain, France, and Switzerland failed to reach agreement. To the others, the British representative appeared unable to accept any systematic approach; he wanted to discuss all potential problems before making a decision. The French and Swiss representatives agreed to examine everything before making a decision, but then disagreed on the sequence and scheduling of operations. The Swiss, being more pessimistic in his planning, allocated more time for each suboperation than did the French. As a result, although everybody agreed on its validity, they never started the project.

In: International Management, 5th ed., 2003, p. 187

8.1 The necessity of multicultural teams

With the increasingly diverse workforce of this century, managers in today’s multicultural organizations will need skills to realize the full potential of both domestic work teams and cross-border alliances. The ability to develop effective transnational teams is essential in light of the ongoing proliferation of foreign subsidiaries, joint ventures and other transnational alliances.

“Multinational groups of many types are evident: the management team of an international joint venture, a group developing a product for multiple-country markets, a group responsible for formulating an integrated European strategy, a task force charged with developing recommendations for rationalizing worldwide manufacturing, and, increasingly, even the top management team of the firm itself” (Hambrick /Davidson/Snell/Snow, 1998, p. 181).

The term “multicultural teams” describes compositions of team members from several countries who must rely on group collaboration if each member is to experience the optimum of success and goal achievement. To achieve the individual and collective goals of the team members, international teams must provide the means to communicate the corporate culture, develop a global perspective, coordinate and integrate the global enterprise, and be responsive to the local market needs.

Group multiculturalism

- Homogenous groups, which are characterized by members who share similar backgrounds and generally perceive, interpret, and evaluate events in similar ways. An example would be a group of male German bankers who are forecasting the economic outlook for a foreign investment.

- Token groups, in which all members but one have the same background. An example would be a group of Japanese retailers and a British attorney who are looking into the benefits and shortcomings of setting up operations in Bermuda.

- Bicultural groups, which have two or more members of a group, represent each of two distinct cultures. An example would be a group of four Mexicans and four Canadians who have formed a team to investigate the possibilities of investing in Russia.

- Multicultural groups, in which there are individuals from three or more different ethnic backgrounds. An example is a group of three American, three German, three Uruguayan, and three Chinese managers who are looking into mining operations in Chile.

In: International Management, 5th ed., 2003, p. 185–186

8.2 Challenges for multicultural teams

The role and importance of international teams increases as the company progresses in its scope of international activity. Similarly, the manner in which multicultural interactions affect the firm’s operations depends on its level of international involvement, its environment, and its strategy. For multinational enterprises, the role of multicultural teams again becomes integral to the company; since the teams consist of culturally diverse managers and technical experts located all around the world or at different subsidiaries.

“Situations in which a manager from one culture communicates with a native of another culture (one-on-one) or supervises a group from a different culture (token groups) can be quite difficult. What happens in work or project groups with members from two cultures (bicultural group) and in those with members representing three or more ethnic backgrounds (multicultural groups)?” (Kopper, 1992, p. 235)

The team’s ability to work together effectively is crucial to the success of the company. However, each group member has a different perception of his or her contribution towards effectiveness and efficiency. Smith/Berg (1997, p. 7) have described in which ways those perceptions can differ:

- “acceptance of authority

- goal building process

- motivation

- corporate strategy

- time management

- decision making process

- conflict solution

- emotions”

Moreover, in culturally diverse groups, the perceptions of team members can widely differ as far as the analysis, the process situation itself, the evaluation and the contribution each team member has to deliver are concerned (Schroll-Machl, 1995, p. 212). In such a situation, the team members are looking for orientation and help which is normally part of their own cultural background. The logical consequence out of this scenario is quite obvious: irritation and mistrust will arise, because the expectations are not in line with the relevant perceptions. The situation will become worse if companies do not interculturally prepare their staff for international assignments.

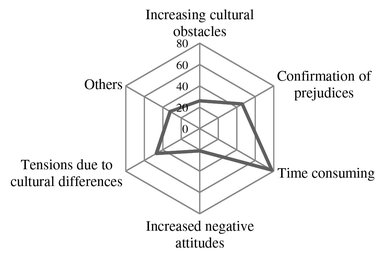

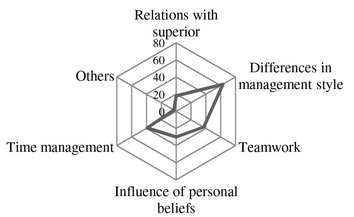

The “Zürich-Versicherungs-Gesellschaft” belongs to those companies which have recognized the importance of providing intercultural training. A seminar entitled “Working Together in a Multicultural Organization” underlines the readiness of the company to prepare their staff for working in multicultural teams. The reasons for those intercultural trainings can be found in an analysis the company had carried out (Saunders, 1995, p. 94):

8.3 The multicultural learning process

In a multicultural team, it is necessary to understand that the diversity of the team members is the starting point for any successful diverse team. The old approach that diversity is given and over the time problems will be solved in a certain way is outdated and counterproductive. If you want to have success for such a multicultural group, any team member has to show the willingness to be actively involved in learning situations.

Which are the stimulating factors that help to overcome learning problems? In a study, Smith/Berg (1997, p. 9–12) asked participants about their opinions. Some of the factors that could stimulate the learning process are described here:

- “a positive as well as a negative feedback

- an environment that appreciates openness

- no lies

- the acceptance of mistakes

- sufficient time for the analysis of mistakes

- active listening even if a bad message has to be communicated

- open exchange of experiences

- an atmosphere that stimulates the learning process and honors a good performance”

In order to find out which elements can obstruct the intercultural learning process, Smith/Berg (1997, p. 10–11) asked the participants to describe a situation in which they had the opportunity to learn something new but did not have the chance to realize it. Afterwards, they should name the reasons that did hamper this realization process. The following arguments were named:

- “lack of information

- fear

- not sufficient time for mutual reflection

- the imagination one can escape from problems

- a negative climate that allows recrimination

- not sufficiently qualified teachers and mentors

- focus on egocentric needs”

With the help of this exercise, Smith/Berg could identify factors that facilitate the start of a positive learning process, which is a decisive prerequisite for the cohesion of a multicultural team. Long before such a team actually starts with a project, every team member has to keep the basic principal of “learn how to learn from each other” in mind.

“It provides a way for potential group members to prepare for the learning that will be needed as they get started. It reveals a universality at the level of learning process that undergrids their experience even when the specifics of that experience vary widely. It encourages all to recognize that some environments are not hospitable to productive group life. This helps them to be more understanding and patient with each other when group crisis occur. It also inspires them to put energy into altering the context as a means of increasing group effectiveness, energy which serves as an antidote to the natural tendency to blame each other when, inevitably, the group encounters bumps in the road.” (Smith/Berg, 1997, p. 9)

8.4 Multiculturality and group formation

Culturally diverse groups have members from different nations and from different cultural backgrounds. One of the most challenging tasks is now how to bring all these differences positively together in order to come to a common group understanding.

“For a multi-cultural group to function effectively it is important for its members to know that the unique contributions each brings will be listened to, understood and embraced. This is not easy to achieve when such groups are left to navigate group formation on their own.” (Smith/Berg, 1997, p. 9)

Based upon the perception that all members of a multicultural team share a lack of information as far as the relevant cultural understanding of the other team members is concerned, an intercultural preparation for working in such a team is required.

“For example, individuals of two different nationalities tend to know, assume, and perceive different things about their respective countries.” (Walsh, 1995, p. 285)

In order to avoid prejudices and stereotypes right from the beginning, Smith/Berg suggest to start with the following exercise: The participants will be separated into groups of people from the same geographical area. Afterwards, the participants should describe events that happened in the selected region during a certain time period (1980s/1990s/2000s).The focus should be on social and economic issues and about 10–20 situations should be listed. The variety of potential topics, like the European Union, the breakdown of communism, the importance of the Asian region, in particular China, the population growth, the environment, and the aggravating unemployment situation, reflect the diverse thinking of the participants and shall help to create a completely new picture of opinions and trends.

With this in mind, everybody will understand that the world is far more different than they have been aware of until now. The logical conclusions for the participants should be:

- There is a lot of information we have never heard about.

- Each participant recognizes that one can personally contribute to a better understanding of this part of the world.

- Such a brainstorming is helpful in order to get a different view about things that happen in a distant area.

- There is a common understanding that things happening in one part of the world will also happen in another part of the world after a while.

- The world becomes more and more interdependent.

- The participants get the feeling that the description of different cultural standards is good for group cohesion.

- This exercise underlines that everybody has only a rudimentary knowledge of the world and that there is much more to learn about it.

Drinking beer

(Carté/Fox)

Two firms in the brewing industry, one German and the other Japanese, were in the final stage of negotiating a contract. Neither side was prepared to concede on some minor details. It was Sunday afternoon in one of the Japanese company’s breweries. The German team asked for a break, and, when offered drinks, requested some beers – they were in a brewery, after all. The Japanese left the room. Instead of the usual 10 minutes, the break lasted nearly an hour. On their return, the leader of the Japanese delegation bowed deeply and said they were now prepared to accept all the remaining demands the Germans had made. The delighted Germans and considerably less enthusiastic Japanese shook hands on the deal. Only later did the Germans discover that their request for alcohol had been interpreted by the Japanese as a subtle: “Accept our demands or the deal is off.” Traditionally in Japan, alcohol only comes out to celebrate an agreement.

In: Bridging the culture gap, London 2004, p. 133

The learning process is not only determined by the exchange of general information. In the next step, the question should be discussed which experiences the participants have already made as far as their group experiences are concerned. For this purpose, Smith/Berg suggest the following exercise: Each team member, who will become part of a multicultural team, is asked to develop 8–10 rules that are accepted in his or her home country. Afterwards, the participants from different countries are divided into several groups in order to exchange their opinions towards their group experiences. After the discussion has been finished, each group has to present their discussion results. At the end, all participants should agree on ten common rules that are binding for all team members.

This exercise makes clear that there are different cultural views which can have a strong impact on the success of the teamwork. Therefore, it is necessary that such an exercise takes place before a multicultural team starts with the project. All the stereotypes that negatively influence the group formation process can be discussed very openly. Furthermore, the already broad discussion about cultural differences will enable everybody to develop a better understanding of the cultural background of those participants that will become member in a multicultural team.

The following polarizations have been found in multicultural teams (Smith/Berg, 1997, p. 12):

- confrontation versus harmony

- individualism versus collectivism

- task- versus process-orientation

- direct versus indirect criticism

- productivity versus creativity

- quality focus versus quantity focus

- authoritarian versus democratic decision making process

Success criteria for multicultural teams

(Indrei Ratiu)

- Do the members work together with a common purpose? Is this purpose something that is spelled out and felt by all to be worth fighting for?

- Has the team developed a common language or procedure? Does it have a common way of doing things, a process for holding meetings?

- Does the team build on what works, learning to identify the positive actions before being overwhelmed by the negatives?

- Does the team attempt to spell out things within the limits of the cultural differences involved, delimiting the mystery level by directness and openness regardless of the cultural origins of participants?

- Do the members recognize the impact of their own cultural programming on individual and group behavior? Do they deal with, not avoid, their differences in order to create synergy?

- Does the team have fun? (within successful multicultural groups, the cultural differences become a source of continuing surprise, discovery, and amusement rather than irritation or frustration.)

In: Managing Cultural Differences, 1991, p. 32

The problem now is how to bridge these different poles. This is a very challenging part in the teambuilding process, because the cultural understanding of the team members differs in many ways. With this exercise in mind, everybody is fully aware of the divergences and the logical conclusion for all is to find a compromise in which the different cultural aspects and views are settled.

“As members acknowledge the range of differences that exist within a multinational group, we observe several things happen. First, there is surprise that this exploration was easier than expected and that it felt collaborative and non-threatening. Second, there is an emerging excitement that membership in this group could be rewarding.

Third, there is anxiety over how they are going to manage these differences which are now out in the open and much more difficult to ignore. Fourth, there is fear that the group will be paralyzed by the tensions that will naturally arise as a result of the differences among the members. Finally, there is a wish that these differences can be regulated, controlled, and subordinated to the collective purpose of the group.” (Smith/Berg, 1997, p. 11)

8.5 Multicultural team effectiveness

The potential benefits and difficulties posed by a cultural diverse workforce and a multicultural marketplace are crucial challenges for the future that companies must manage in a positive way. In achieving the greatest amount of effectiveness from diverse teams some parameters determine the success or failure of such a multicultural team.

8.5.1 Conflict as a chance

A former study from Smith/Berg (1987) has found out that team members are ready to bow their own goals to that of a team. Nevertheless different positions and views can lead to conflicts within a team and can hamper the effectiveness of the project. Therefore all efforts should be made to look for a positive solution.

“We argue that conflict in groups is a problem primarily because we think of it as a problem. If we saw conflict as a source of group vitality we would seek it out rather than avoid it in and effort to harness it in the service of the group’s mission.” (Smith/Berg, 1997, p. 11)

The conclusion drawn from this study is that conflicts should not be rejected but seen as an element that handled in the right way can be helpful for the further teambuilding process.

8.5.2 Team effectiveness and nationality

Culturally diverse groups have members from different nationalities with different cultural backgrounds. Problems potentially arising in this context can also have a negative impact on the group cohesion and effectiveness. The construct of “nationality” for example relates to the mother tongue, to group experiences made in the home country or the kind of task that had to be fulfilled at a home. All these elements have to be taken into account to guarantee the success of the project.

“When the patterns of differences were analyzed, variations in responses could be partly explained by characteristics such as age, education, job professional experience, hierarchical level, and company type. Less expected, however – particularly in an institution that places great emphasis on an international ethos – was the fact that the nationality of the respondents emerged as an explanation for far more variations in the data than any of the respondents’ other characteristics.” (Laurent, 1991, p. 201)

8.5.3 Team effectiveness and international work experience

Two companies – two different results

As the following extract from a conversation between two executives shows, there is often only a thin line between success and failure of multicultural teams:

“When we first launched our research programme on multinational groups, we discussed it with a group of senior executives from major multinational corporations. The comments of two executives, both from European-based companies, symbolize the complexity and subtlety of the issues involved. One executive said: ‘I don’t see why this is an important topic of study. Our company puts people of different nationalities together all the time. It’s how we do business: there is nothing particularly special about such groups. What’s the big issue?’”

The second executive responded:

“Wait a minute. In my company, we are having great difficulties with such groups. We’ve had strategic plans suffer and careers derail because complications arising from multinational groups. Just last month we killed a global product development project because the team had taken so long that the competition had already sewn up the market.” (Hambrick/Davison/Snell/Snow, 1998, p. 182)

In a study carried out by Hambrick/Davison/Snell/Snow (1998, p. 182), the scientist have combined the factor “nationality” with the construct of “international work experience” and came to the conclusion that those team members who possess international work experiences are better used to work in a multicultural teams in comparison to those lacking this experience. Moreover, if a company has an international corporate structure, the element “nationality” will be replaced by the identification with the new enterprise.

As far as the effectiveness of multicultural teams is concerned, Watson (1993, p. 590) has found out that time will play an important role for the success of any multicultural team. On the one hand, he pointed out that without a sufficient intercultural preparation for all team members – even though it is time-consuming – the success is not guaranteed. On the other hand, he underlined the importance of international work experiences of some team members, which can facilitate the teambuilding process mainly in the initial phase.

8.5.4 Team effectiveness and language

In the past, managers talked about the need for faster and more efficient communication, as if speed would guarantee effective communication. They paid lip service to the need for good intercultural communication, but staffing decisions were typically rather based on technical knowledge than on good language skills. In order to give instructions, a manager has to have a good command of the relevant business language. Even if the manager is fluent in English, the surface knowledge, the speed of speaking and a good accent might hide the fact that this person misses many of the fine points which can be important for doing business (Varner /Beamer, 2011, p. 432). There is a vast difference between being reasonably functional in a language and being bilingual and bicultural. A lot of problems derive from related misunderstandings, regardless whether a manager or team members are addressed.

“The influence of language proficiencies in a multinational group setting has been observed to be profound. For example, an individual’s facility with the group’s working language greatly affects one’s amount and type of participation, as well as one’s influence in the group.” (Gudykunst, 1991, pp. 5f)

In another study, Gehringer (1988, p. 214) found out that a good command of the language that is used in a multicultural team has a significant impact on the success of a multicultural team, respectively in a joint venture situation.

“The simple ability to communicate with one’s counterpart in a partner firm often makes a significant difference in a JV’s prospects for success; the absence of this ability has caused more than a few disasters.” (Geringer, 1988, p. 214)

Our studies carried out in France and Germany (2008–-2012) have also come to the conclusion that without the suffiecient knowledge of the respective business language, misunderstandings will occur and the project is at risk to fail.

If one takes a look at the relation between language and the task itself, there are different correlations to be observed.

“[…] the harmful effects of limited shared language facility will be greatest for groups engaged in coordinative tasks, least for computational tasks, and in-between for creative tasks. Increases in shared language facility result in corresponding increases in group perfor-mance for each type of task” (Hambrick/Davison/Snow/Snell, 1998, p. 198)

Compromise

(Helen Deresky)

In Persian, the word “compromise” does not have the English meaning of a midway solution which both sides can accept, but only the negative meaning of surrendering one’s principles. Also, a “mediator” is a meddler, someone who is barging in uninvited. In 1980, United Nations Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim flew to Iran to deal with the hostage situation. National Iranian radio and television broadcast in Persian a comment he was to have made upon his arrival in Tehran: “I have come as a mediator to work out a compromise.” Less than one hour later, his car was being stoned by angry Iranians.

In: Managing Across Borders and Cultures, 2000, p. 177

“When a team outgrows individual performance

and learns team confidence,

excellence becomes a reality.”

(Joe Paterno)

8.5.5 Team effectiveness and international composition

The composition of a multicultural team plays an important role for the success of any project. Hambrick (1998, p. 192) and the OCCAR study carried out in 2008, which will also be presented in this chapter, underline the fact that the more nationalities are represented in a team composition, the more difficulties the team has to face. One the other hand, the belief that representatives with a similar cultural background would form a good team is questioned by the study of Hofstede. In his 5-D-study and particularly the individualism dimension, he has made clear that the differences, e.g. between Finland and the United States of America, might be significantly higher than one would normally expect.

Moreover, if one believes a team composition with members from neighboring countries can become a cornerstone for the success in a multicultural team, one has to realize that there are a lot of tensions among different countries tracing back to historical events. Representatives from Japan and Korea might face similiar problems like members in a team coming from Greece and Turkey or from Vietnam and Cambodia. Whether this kind of heterogeneity has a positive or negative impact depends on the tasks that have to be fulfilled.

8.5.6 Team effectiveness and the nature of the task

A lot of studies (Hoffmann/Maier, 1961, pp. 401–404, Rothlauf, 2012, pp.12–15) have come to the conclusion that normal tasks are better solved by a homogeneous group. However, if the task is not quite clearly defined and if there are no standard solutions at hand, the composition of a heterogeneous group proves to be more suitable. In terms of effectiveness and creativity, Hambrick/Davison/Snow/Snell (1998, p. 195) have found out that a multicultural team would be the best option. Different opinions and views from members with a diverse cultural background create new ideas which can be extremely helpful if the team has to develop products for regional or worldwide markets or has to identify market gaps for new services or products.

“When the group is engaged in a creative task, diversity of values can be expected to be beneficial for group effectiveness. The varied perspectives and enriched debate that comes from increased diversity will be helpful in generating and refining alternatives.” (Hambrick/Davison/Snow/Snell, 1998, p. 195)

If the task requires an analysis of a lot of facts and figures based upon objective criteria, the nationality as well as the cultural value system can be neglected for a successful collaboration within a multicultural team.

“When the group is engaged in a creative task, diversity of values can be expected to be beneficial for group effectiveness. The varied perspectives and enriched debate that comes from increased diversity will be helpful in generating and refining alternatives.” (Hambrick/ Davison/Snow/Snell, 1998, p. 195)

If team interaction is required as part of the task, the correlation is negative (Hambrick/Davison/Snow/Snell, 1998, pp. 197–198). Now the value diversity of the team members plays an important role and it takes time to find a consensus among them, especially if a critical situation has to be managed.

“However, when the task is coordinative, involving elaborate interaction among group members, diversity of values will tend to be negatively related to group effectiveness. In such a task situation, fluid and reliable coordination is required; debates or tensions over why or how the group is approaching the task - which will tend to occur when values vary - will be counter-productive. In addition, disparate values create interpersonal strains and mistrust which become damaging when the group is charged with a coordinative task.” (Hambrick/Davison/Snow/Snell, 1998, p. 197)

Moreover, there are some studies (Bantel/Jackson, 1989, Eisenhardt/Schoonhoven, 1990, Hambrick, 1996) taking a look at the relationship between the multiculturalism of the top management and its effectiveness. They all came to the conclusion that there is a positive correlation between task orientation and the heterogeneity on this managerial level.

Managing multicultural teams

(Brett/B ehfar/Kern)

The structure of a team is usually flat meaning that everybody has the same right and is treated equally. However, the flat structure of a team might be uncomfortable for a member who is coming from a culture where he or she is used to have a strict hierarchy and people are treated differently according to their status in the organization. The opposite situation can occur, when there is a strict hierarchical structure in the team that might be humiliating for teammates coming from egalitarian cultures.

The most serious violations of hierarchy occured when a junior-manager from a low-context culture was sent to contact or negotiate with a senior manager from a high-context culture, since this was seen as disrespectful from the point of view of high-context cultures. For example, in one US-Korean team of due diligence US team members were having difficulties with accessing information from their Korean team members. Therefore, Americans decided to complain directly to the Korean management, which offended higher-level Korean management, because Korea is a culture with a high power distance according to Hofstede. Koreans would have accepted complaints from at least same level manager, but not from the lower-level. Moreover, such an action of their American team members created tensions within the team. This conflict was only resolved when higher-level managers from US visited Korean higher-level managers with an apology and a gesture of respect.”

In: Harvard Business Review, November 2006, p. 87

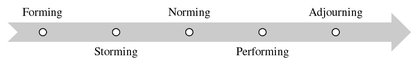

8.6 Tuckman’s stages of group development

In the course of analyzing his study results on group development, Tuckman (1967, pp. 25ff) originally identified four stages, which he characterized in terms of group structure and task allocation:

8.6.1 Forming

In the first stage of group formation, members get to know the other group members and try to figure out what kinds of behaviors are expected. In multicultural groups, this stage is likely to be fraught with problems because people tend to distrust anyone but themselves – generally because of a lack of understanding. All kinds of verbal and nonverbal behavioral differences can lead to misinterpretation, which in turns leads to mistrust or dislike. Employees’ expectations about the form of communication, respect for authorities, status and work division often produce variations in their perception of acceptable interpersonal behavior. In order to reduce this kind of possible tensions, some group activities can help to create a good climate for further collaboration. Playing football or basketball together and/or a multicultural dinner prepared by all group members are some good examples how mutual trust can be steadily developed and how the most important part of the team building process, namely cohesion, can be achieved in the long run.

8.6.2 Storming

The biggest challenge of this stage is how the group defines and responds to its task and what type of group structure emerges. Even in homogeneous groups, this is often a period of hostility and conflict, as group members have emotional responses to their commitment to the task and to emerging leadership patterns. In diverse groups, even greater conflict may arise because members may bring varying expectations with them about who is capable of doing what. The tendency of some people to stereotype others rather than to consider their skills and potential contributions to the group objectively can cause serious problems which have to be solved in order to successfully continue with the group project. An important part of creating a positive climate is to show that the skills of all group members are valued. Either in this phase or in the previous forming phase, the group has to develop team rules that are at the end of the discussion process binding for all group members.

8.6.3 Norming

The key issue at this stage is the ability of the group to further build up cohesion. Cohesion requires to accept everybody’s role in the team. In this phase, group members establish a consensus on norms of behavior within the group with the aim of becoming united. The achievement of such consensus is not as easy, especially in a culturally diverse group with members from different cultural backgrounds and varying values. This stage is the most important one in the teambuilding process, because the danger of a failed teamwork project can become a reality. The success of the team therefore depends on whether the group was able to develop trust and respect in the initial stage.

8.6.4 Performing

Once the group has developed that kind of cohesion necessary for a successful collaboration, it can turn to the actual work stage and concentrate on the tasks for which it was created. A mature group – one that has worked through its problems and reached a concensus on allocating roles in the light of the group’s needs for expertise and leadership – should be productive. At the end, the actual accomplishments of the group are realized at the performing stage: The relative level of effectiveness or productivity depends on how well the group’s diversity has been managed.

8.6.5 Adjourning

Later Tuckman also added a fifth phase, which describes the completion of all tasks as well as the termination of the group work. The manager is required to keep this phase as short as possible and to assist the team members in finding new fields of activity and tasks.

Fig. 8.1: Tuckman’s five stages of group development

Source: Own illustration based on Tuckman, pp. 25ff

8.7 Multicultural team building

As businesses success depends upon effective cooperation and communication within teams, intercultural business structures have been radically transformed over the past few decades. Changes in areas such as communication and information technology and shifts towards global interdependency have resulted in companies becoming increasingly international and therefore intercultural. In addition, the need to “go global” and to cut outgoings is demanding that companies protect international interests whilst keeping down staff numbers. The solution in most cases has been the forming of intercultural teams. However, the intercultural dimension of today’s teams brings new challenges. Successful team building does not only involve the traditional needs to harmonisse personalities but also languages, cultures, ways of thinking, behaviours and motivations.

Over the last decade, a lot of research work has been done in the framework of Bachelor- and Master Theses regarding the collaboration within multicultural teams. Companies like German Lloyd, Rickmers GmbH & Cie.KG, or OCCAR were part of our studies. Interviews with Don A. Neuman, who is the manager and chief pilot of domestic and international flight inspection for the Federal Aviation Administration in Atlanta, with Tom Dinkelspiel, CEO at the Swedish Investment Bank Öhman, or with Dr. Boll, Head of Corporate Office of Internationalization, Bosch GmbH, only to name a few, made clear that there are some advantages as well as disadvantages that occur if members with a different cultural background have to work together. Because of the assurance to treat all information strictly confidential, only some general observations will be described in the following.

Intercultural teams have an inherent disadvantage. Cultural differences can lead to communication problems, unpredictability, low team cohesion, mistrust, stress and eventually poor results. However, intercultural teams can in fact be very positive entities. The combination of different perspectives, views and opinions can lead to an enhanced quality of analysis and decision making while team members develop new skills in global awareness and intercultural communication. Normally, one can expect a different viewpoint that broadens the horizon of each team member and leads to a greater diversity of ideas, which enables the members to be extremely creative. Moreover, each team member can personally benefit from the work within a multicultural team and can promote their career.

However, in reality, this best case scenario is rarely witnessed. More often, intercultural teams do not fulfill their potential. The root cause is the fact that, when intercultural teams are formed, people with different frameworks of understanding are brought together and expected to naturally work well together. However, without a common framework of understanding, e.g. in matters such as status, decision making, communication etiquette, this is very difficult, and thus requires help from outside to truly commit to the team.

Again, it becomes obvious that without a qualified intercultural training the overall goals of a company cannot be met. A good intercultural training is the decisive factor helping to bind a team together. Through an analysis of the cultures represented in the team, their particular approaches to communication and business and how the team interacts, intercultural team builders are able to find, suggest and use common grounds to assist team members in establishing harmonious relationships.

Multicultural Team Building

(Elashmawi/Harris)

As the result of team-building activities, which rested in a better understanding of cultural differences and working toward common goals, participants came up with the following motto:

Together Everybody Achieves More (TEAM)

In: Multicultural Management 2000, p. 260

Intercultural training sessions aim at helping team members to understand their differences and similarities in areas such as status, hierarchy, decision making, conflict resolution, showing emotion and relationship building. From this basis, teams are tutored how to recognise future communication difficulties and their cultural roots, empowering the team to become more self-reliant. The end result is a more cohesive and productive team.

Many exercises are offered for team trainings. The following are the major ones used for intercultural team development (Reinecke/Fussinger, 2001, p. 179):

- “Contact exercises

- Sensitisation- and awareness exercises

- Role plays about the own culture and its values

- Exercises on flexibility

- Creativity- and communication exercises

- Team exercises

- Reflection exercises

- Closure exercises”

Therefore, the concept of intercultural team training is divided into the following five steps:

Tab. 8.1: Stages of the intercultural training,

Source: Reineke/Fussinger, 2001, p. 180

| Analysis | • What is the goal? |

| • Where are we? | |

| • What are our hurdles of working together effectively? | |

| • What are our quirks? | |

| Clarification | • of the situation |

| • of relationships | |

| • of problems | |

| • of goals | |

| • of resources | |

| Feedback | • Personalities: characteristics and preferences |

| • Feedback exercises | |

| Agreement | • Goal orientation |

| • Action plan | |

| • Rules and structures | |

| Reflection | • What happened? |

| • How did we model our situation? | |

| • What and how do we want to use our experiences? |

In conclusion, for intercultural teams to succeed, managers and HR personnel need to be attuned to the need for intercultural training in order to help cultivating harmonious relationships. Companies must be supportive, proactive and innovative if they wish to reap the potential benefits intercultural teams can offer. This goes beyond financing and creating technological links to bring intercultural teams together at a surface level but goes back to basics by fostering better interpersonal communication. If international businesses are to grow and prosper in this ever contracting world, intercultural synergy must be a priority.

Interview with Tom Dinkelspiel, CEO at the Investment Bank Öhman:

| Students: | What are the risks for a project manager of a multicultural project? |

| Dinkelspiel: | There can be difficulties in assessing the skills and competencies of team players. Training and education standards and the relative value of qualifications can be very different in different parts of the world. |

In: Projektunterlagen, Bachelor- und Masterarbeiten, Stralsund, 2000–2009

8.8 A study on multicultural teams: The OCCAR example

Abdelkarim El-Hidaoui, Monika Fehrenbacher, Michaël Koegler and Yvonne Kempf, students of the Université de Haute-Alsace, were part of a research project with a specific focus on staff members of the OCCAR in 2008. The Organisation Conjointe de Coopération en matière d‘Armement (Organization for Joint Armament Cooperation) is an intergovernmental organization with the aim to provide more effective and efficient arrangements for the management of certain existing and future collaborativee armament programs. Currently, the member states are Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom. Some of the group’s findings can be found below.

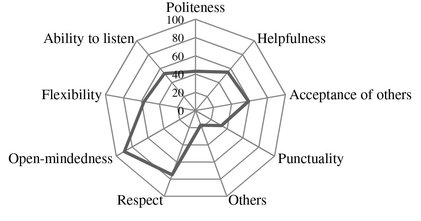

1) What are the positive effects of culturally diverse teams?

2) What are the negative effects of culturally diverse teams?

3) What do you expect from your colleagues?

4) Have you ever been confronted with cultural conflicts arising from…

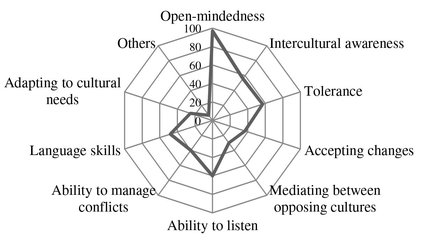

5) Which managerial skills are important for an efficient intercultural team?

In: El-Hidaoui/ Fehrenbacher/ Kempf/ Koegler, International Teams – Practical application regarding to the teamwork of OCCAR, Mulhouse, 2008, unpublished

8.9 Questionnaire on cross-cultural teamwork (extract)

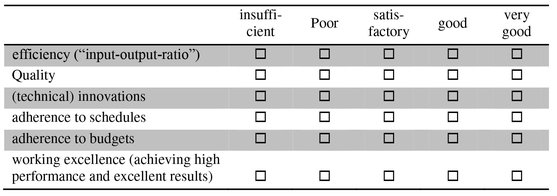

The following questions were taken from a questionnaire with 128 questions on cross-cultural teamwork. They can be provide a basis for assessing the work of one’s own multicultural team and analyzing the cultural influences on the team’s performance.

- Which language do you normally use when working in the team?

- How would you rate your knowledge of the team’s business language?

□ insufficient (5) □ poor (4) □ satisfactory (3) □ good (2) □ very good (1)

- If you have marked 2–5, what are the impacts on the team work?

You sometimes back off in the discussion.

Some things remain unclear and open.

Misunderstandings occur.

You sometimes have difficulties to understand what others say.

You sometimes have difficulties to follow the team’s discussions.

Sometimes, you cannot fully apply your skills. - Please mark the appropriate space.

- Prior to the actual teamwork, we got the chance to get to know each other.

□ one □ some □ many □ all □ none

- Which different nationalities are part of your team? How many team members belong to each nationality?

- Please describe your tasks within the team.

□ rather routine/simple □ rather innovative/complex □ both

- Communication within the group takes place…

- How would you evaluate your team’s performance regarding…?

- Please state with how many of your team colleagues you would like to continue to work in the future:

□ at least one □ the majority of them □ all □ none of them

- Please state how much you would like to work on further projects with the same group:

□ not at all □ rather not □ maybe □ readily □ gladly

Source: Herrmann, D., in: Multikulturelle Teams – Ein Risikofaktor in der Projektarbeit, Passau 2009, Auszug aus einer Diplomarbeit, unpublished

8.10 Exercise: Cross-cultural team building scale

All human beings have values preferences that significantly impact work group cohesion. To see your values profile, mark an X along the continuum for each item and then connect the Xs. The benefit from this exercise to your team is that you will all see where the similarities and differences are. From there, the next step is to discuss how to turn your individual differences into a collective advantage.

“It is much more rewarding to get to the top of the mountain

and share your experience with others

than to show up by yourself, exausted.”

(Shandel Slaten)

8.11 The experts’ view

8.11.1 Interview with Jerry Holm, DB Schenker

The BMS students Anna Dünnebier and Matthias Hoffmann had an interview with Jerry Holm, Trade Lane Manager for South-East Europe within the DB Schenker Concern in Gotheburg on 22nd November 2011. Here are some of his answers:

Students: What is your general understanding of the term “international teams”?

Holm: Although all human beings are living in different countries with different mentalities, habits and thinking, they must all work in a network, because you should help each other to build up a network, which should be as perfect as possible.

Students: When you are planning an international team meeting, which planning steps, according the relevant time requirements and the introduction phase, are necessary?

Holm: DB Schenker used to organize development meetings at the head quarter in Essen, Germany. Such meetings are planned for all important members within the company from all around Europe. The schedule during such meetings provides group meetings for all participants and workshops to develop new ideas and solutions. In these workshops, consensus and strategies will be developed, which come into force in the regional departments. In a start-up phase the new ideas will be discussed and finally set into action.

Students: Which advantages/disadvantages do you see as far as international teams are concerned?

Holm: I suppose that you have many possibilities to move around. If you are young you can start at the company in the country you like and the level you like. The disadvantage in working for a big company is that you could feel sometimes as a number and your influence on the decision-making process is very modest.

Students: What do you think about modern communication tools? Which are used frequently?

Holm: With the modern telecommunication system that is offered nowadays the communication exchange has become much easier. We have many conference rooms which are equipped with a video-system; because it is a way to save time and money, but I think it will never take away the need of meeting a person face to face, especially if trust and confidence play a vital role. Very problematic is the usage of too many E-mails. I think people have to be trained to use this tool wisely, that means only if it is absolutely necessary.

In: Dünnebier/Hoffmann, Written Assignment, Stralsund 2012 (unpublished)

8.11.2 Interview with Heidrun Buss, AHK Guangzhou

Heidrun Buss is the Executive Chamber Manager at the Delegation of German Industry and Commerce (AHK) Guangzhou in China.. An extract from the interview conducted by the students Pia Boni, Anna Prötzig and Caroline Friemel in July 2012 provides insights into working in multicultural teams.

Students: How important is working in multicultural teams for you?

Buss: It is very important to me. Problems can never be solved alone and you always need a specialist. If a company has problems with taxes you need to talk to your legal department. Or you talk to another guy who has already had the same problem and knows how to solve it. Especially in a foreign country you need to get as much information as possible because you don’t know how to solve problems. In China you need to collect much more information and consult more people.

Students: In which way do you have to adapt to your team members and their cultural specifics?

Buss: We have the Chinese New Year holiday where they have to have holidays. So we need to take this into account if you have any big projects. There are companies, not our company, where they consider the Chinese habit of sleeping after lunch. They always schedule meetings after 1.30 pm, because they know their Chinese colleagues have a break before that. In my part of China the people speak Cantonese, so on business meetings I always ensure to have someone with me who speaks that language. From the religious point of view we do not see any obstacles doing business in China.

Students: What are the strengths in working in a intercultural team?

Buss: It is definitely the different input and ways how to approach things. The other persons might know of other obstacles we didn’t think of. In overall it is the enrichment for the whole project; to have different directions and opinions. It might be more difficult to come to an agreement later but at first it is broadening the whole view, so in the end you have better results.

Students: How important do you think is time management for working in a multicultural team?

Buss: Very important because time concepts are totally different in every nationality and you don’t know that if you have never thought about that before because normally you might assume if you set a deadline on 5 pm you think you have it by then. What about the consequences? Especially the Chinese people don’t see the whole picture. They don’t know that if they miss their deadline by one day or even the next morning the whole process is screwed. It is very important to have a plan and to make sure they know what the problem is if they don’t do their work.

In: Boni/Prötzig/Friemel, Written Assignment, Stralsund 2012 (unpublished)

8.12 Role play: Multicultural team work

The following role play was created by the students of Baltic Management Studies at the University of Applied Sciences Stralsund, Juliane Wormsbächer and Christoph Kolbin.

At the end, you are asked to find out, how the managers in the role play behaved based on their cultural background. Furthermore, write down the mistakes you have found as far as Dr. Wagner’s behavior is concerned and let us know what your solution looks like.

(Part 1)

The American, the German and the Chinese company representatives of “Colors United”, Mr. Peter Smith, Dr. Wagner and Mr. Byung Ningchu, meet in Berlin at 10 o’clock in the morning, since several decisions concerning the production of a new sports suit have to be made. After the greetings, they all take their assigned seats.

(Part 2)

| Wagner: | As you all know, we have already selected the material and have developed a design for the jacket as well as for the pants. Today we will talk about the colors and the motifs or symbols and the name for our new sports suit. |

| Smith: | (He interrupts the German and looks at his notes while starting to speak.) Let me comment on the design of the jacket and the pants. Our research and marketing team has just finished a couple of series in research concerning design and style trends for the upcoming year. We would suggest shortening the collar of the jacket and tightening it around the neck. This would make it look sportier; the same can be said for the pants. The trend seems to go in a direction where tight pants will be asked for. We suppose that our product would fail and would not be able to compete with other products on the market if the changes weren’t made. We’ve already produced a few suits in the modified style and even carried out a survey with both suits. We asked people which of |

| them they were more likely to buy and the one with the changes was 40 % ahead. We’ll soon be able to send our new plans to our partners in China so that they can adjust the production. | |

| Wagner: | So, what you are trying to say is that we should change the design we have previously agreed on? Do I understand you correctly? We have spent most of the time on questions related to the design and we have all agreed that this design will be competitive on the market. |

| (He pauses for a moment) I would say we leave the design as it is. | |

| Smith: | Trust me! (a bit angry) We have spent a lot of time discussing these changes with the development group. Our efforts to change the design will be rewarded. I’m absolutely sure about that! |

| Wagner: | I still don’t agree with changing anything. We have planned our work and now have to implement our plan. There is no room for changes. |

| Smith: | What is your opinion, Mr. Ningchu? |

| Ningchu: | I have to agree with Dr. Wagner! We have spent a lot of time on the design and it seems to be good. But your team has done all those researches and if the trend goes towards what you’ve just said, it will be important to make the changes because we are going to launch a product with which we want to be successful and if the changes are necessary for that, we should consider them carefully. |

| Smith: | (impatiently asking) So, do you say we should make those changes? |

| Ningchu: | Well, we would have to discuss that within our group in China. I can’t decide that on my own. |

| Smith: | But we are running out of time, we need to finalize the changes and send them to China so you can implement them. Don’t you think your colleagues would agree to these changes as much as you do? |

| Ningchu: | I understand that we have a tight schedule, but I’m unable to decide this matter without having discussed anything within the group. |

| Wagner: | Gentlemen, we are losing precious time. Let us get back to our actual topic. We can talk about possible changes if we still have time later on. |

(Part 3)

(The managers get up from their seats and say goodbye to each other.)

In: Kolbin/Wormsbächer, Written Assignment – Role Play, Stralsund, 2006 (unpublished), pp. 8ff

Interview with Don A. Neuman

Manager and chief pilot of flight inspection for the Federal Aviation Administration in Atlanta:

In: Projektunterlagen, Bachelor and Master Theses (all unpublished), Stralsund, 2000–2009

8.13 Case Study: Managing diversity at Luxury Island Resort

Patricia Atwell had just accepted a position as a human resource consultant for the Luxury Island Resort in California. The resort’s profitability was declining, and Patricia had been hired to evaluate the situation and to make recommendations to the local management and the headquarters management. Feeling a little bit overwhelmed by this task, Patricia pondered where to start.

There had been an extremely high employee turnover rate in the past few years, the quality of the resort’s service had declined, and many regular clients were not returning. Patricia decided to start with the clients by interviewing some of them and asking others to fill out a comment slip about the resort. Many clients criticized the poor service from every type of staff member. One regular client said, “This used to be a happy, efficient place. Now I don’t even know if I’ll come back next year; the atmosphere among the workers seems dismal; nobody ever looks happy.”

Patricia began to investigate trends and practices regarding hiring and placement. In reviewing the files, she noticed that the labour pool had become increasingly diverse in the last few years. The majority of the employees at the resort represented a number of racial and ethnic backgrounds, and many were recent immigrants. Many were unskilled and had little schooling, yet there were placed straight into their jobs. The management and office staff was also quite diversified; yet, even with higher education and skill level, there was a considerable turnover.

One day later Patricia decided to get out among the employees – to talk to them and observe them on the job. She started her departmental evaluations in the kitchen, where she found a melange of cultures; the French chef was screaming directions, mostly in French, to his assistants and the waiters, who seemed to be Haitian, Spanish, and Asian. Many seemed confused about what they should do, but did not say anything. After lunch Patricia decided to review the housekeeping department. She observed a new housekeeper who had been hired that day; her name was Sang, and she was a recent immigrant from Taiwan. Sang was given a cleaning cart, an assigned block of rooms, and a key to the rooms; she was told to get to work. That same day there was a customer complaint. Apparently, Sang did not understand the meaning of the sign “Do not disturb” and had interrupted someone taking a shower. Later, she overheard a manager reprimanding another housekeeper, remarking that she was nothing but a “lazy Mexican.” Patricia spoke to the young woman and found out that when the manager noticed her leaning against the wall, she was just waiting for the room occupant to come back out, as he had said he was about to do, so that she could clean the room

Patricia interviewed a couple of the housekeepers. She asked a variety of questions: What did they perceive the job duties to be? How should they be performed? What could be done to improve the job? The assortment of answers she received perplexed her; each housekeeper perceived the job differently, and each had valid ideas for improvement based on his or her understanding of the job. Patricia asked one Chinese housekeeper why she did not bring her suggestions to her supervisor. She replied, “Oh, no! I could not do that. He will only think my ideas are stupid.” At the end of the week, Patricia was disturbed when she observed two of the Chinese housekeepers throw their ballots in the garbage. When she asked them why they had decided not to vote, they said that they could not make such a difficult decision about their fellow workers.

For the following days, Patricia practiced her “management by walking around”, just trying to quietly observe the staff and their interactions. One thing she noticed was that each day the different ethnic groups could be found socializing only among themselves – outsiders were not welcomed. She observed a group of Chinese workers planning a picnic, but as she approached them, they were politely quieted down.

After carefully studying the work processes and interactions in the other resort departments, Patricia decided to interview and evaluate the various managers in the resort, both in the hotel and in the various beach and recreation areas. She started with the restaurants. The manager said that he did not perceive any problems with his staff. When she mentioned some of her observations, he said that he was busy and that he really did not find anything to be concerned about. Next, she approached the manager of housekeeping, Mrs White, who explained that she set the rules and duties and that the only real task was for the staff to follow them; if they did not, she fired them. In consulting with the resort manager, she noticed that he was concerned about declining occupation. However, he explained, he tried not to become involved in employee problems. He said that he hired experienced department managers, and he expected them to be able to handle such problems.

In concluding her evaluation period, Patricia spent a couple of days reviewing her findings. Then she drew up her report and recommendations. Next, she set up two meetings – one with all the managers at resort, and one with the president of the Luxury Island Resorts.

Source: Deresky, H., in: Managing across borders and cultures, New Jersey, 2000, S. 132

Review and Discussion Questions:

- You are Patricia Atwell. Evaluate the situation and tell us what went wrong.

- What are your conclusions out of this scenario? Draw up a list of recommendations to the resort management and a list of recommendations to the company president.

- Assuming your recommendations are accepted, outline your plan for implementing them. What specific steps must be taken, by whom, and when? What results do you anticipate?