The Business Cycle and Documentation

Introduction

Every Command Center in any healthcare facility will have variations in its normal operations. These may be driven by the Command-and-Control model in use, by the content of the Emergency Response Plan, by the nature and characteristics of the emergency, or by the corporate culture. What each has in common is that any truly good and effective Command Center is not simply a reactive process, responding to each issue which arises. A truly effective Command Center should be, if not in the earliest stages, then eventually and as quickly as possible, truly proactive; managing the emergency well enough that events begin to be anticipated, and contingency responses developed and arranged in advance by the Command Center Team. Any experienced Incident Manager will tell the student that any crisis which has already foreseen and has a plan for its resolution in place is no longer a crisis; it is simply another problem which must be addressed.

Similarly, with the Command Center at the heart of the healthcare facility’s decision making during any emergency, and the central “clearinghouse” for information, staff and resources, its preparations for, decisions and actions will undoubtedly be subjected to some type of review, following the conclusion of the emergency. This may be a less formal internal review of events as a part of a quality improvement process, a more formal Coroner’s Inquest or public inquiry, or even some sort of legal or civil challenge regarding performance and liability. In each case, the documentation of precisely what occurred and when may become absolutely critical, and its ongoing occurrence should be a central part of the activities of the Command Center Team.

The process for decision making must not only be organized, timely and appropriate; it must also APPEAR to be all of these things! Moreover, both information and actions are likely to be considered from the perspective of “if it isn’t written down … it didn’t occur.” Fortunately, if the documentation process is formalized in the Command Center, there is a “duty of completion,” and, in most legal systems, such a duty virtually ensures that the documentation generated will be admissible in the review, regardless of the type of review in question. For these reasons, the decision-making process and the actions of the Command Center Team are an essential part of good practice, and they require an appropriate amount of the Emergency Manager’s attention.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the student should be able to describe the documentation processes which are associated with the operation of a Command Center during an emergency in any type of healthcare facility. They should be familiar with the Business Cycle process, the methods and tools required for the creation of an Incident Action Plan (IAP), the need to document all occurrences and decisions, and also resource and information requests, and how these were individually managed. The student should be familiar with progress reporting processes, such as the Situation Report, and with formal summaries of events upon the completion of the emergency response, such as After-Action Reports.

Business Cycle Process

The Command Team and the Business Cycle are the “heart and soul” of the response to any crisis in a healthcare facility

In any Command Center, the Business Cycle (sometimes in the United States called a “Planning Cycle”1) should be a documented, structured process by which those who are tasked with major roles in the management of the emergency will meet, together with the Incident Manager, in order to exchange and analyze information, facilitate the development of the IAP,2 to receive assignments from the Incident Manager, and to report on progress and problems encountered.

The structure of the Command Team will be dictated by which variant of the Incident Command System3 the Team is using, although healthcare settings typically use a specific variant, such as HEICS4 or Healthcare Emergency Command and Control System (HECCS). Each member of the Command Team will fill one of the key roles, whether as part of a preassigned response, or on an ad-hoc assignment from the Incident Manager.

All meetings will occur in the facility’s Command Center. In most circumstances, the Command Team will not meet continuously; after the initial meeting, they will gather periodically, on a schedule determined by the Incident Manager and based upon the current requirements of the incident and the organization, usually once in each Operational Period. At each of these meetings, the current status of the incident and the problems encountered will be reported to the group, and the group members will themselves be expected to report on their own progress. The group will work collectively on determining the goals and objectives to recommend to the Incident Manager; in essence, the “next steps” at each stage of the incident management process. Finally, they will receive additional assignments, where appropriate, and a meeting time for the next meeting.

When circumstances dictate, the Incident Manager may alter the frequency of the Business Cycle meetings, increasing or decreasing the length of the Operational Period,5 based upon the best assessment of the current situation, the identification of new “needs” by those in the field, or a need to reassess the current situation and develop and implement new strategies and objectives. All such meetings will be formal and minute-ed, and chaired by the Incident Manager. All reports, information requests, and resource requests will be logged and assigned to one or more individual team members, and then monitored and tracked for completion. The Incident Manager will be responsible for the completion of the Event Log, and the reporting of incident progress, as appropriate, by means of the Situation Report, and should be supported in these efforts by one or more Scribes.

Immediately upon the completion of the incident, the Incident Manager will hold a final Business Cycle meeting. This will occur in order to obtain final reports and perform a final debriefing of all of the members of the Command Team. All documentation related to the incident will be gathered and collated, and a debriefing of other staff involved in the incident will be staged, if required. The documentation will be used by the Incident Manager, often assisted by the Planning Lead and the Scribe(s), to create a final report on the incident and its response, along with any recommendations for changes and improvements to future responses, normally called an “After Action Report.”6 This document can be circulated to all senior decision makers, and to others, as dictated by individual corporate policy. The After-Action Report, along with all of the documentation collected, and the Event Log, are then sealed and sent for long-term secure storage. In healthcare organizations, this occurs most typically in either in the files of the Incident Manager, or in corporate Risk Management or the organization’s legal department.

The processes described here are essential to the management of the incident. Each measure described contributes to the provision of a formal, structured process for the gathering and analysis of data, and for decision making. The in-depth documentation provides a permanent record of all decisions and actions, and the exact context in which they occurred. Without such a process, months later, the reason why a particular decision occurred at a particular time may be less clear, and therefore, subject to speculation after the fact. By documenting absolutely everything in this fashion, such speculation can be effectively eliminated.

By having both a “duty of completion”7 and by completing all of the documentation at the time of occurrence, the use of such comprehensive documentation during any external review or legal action, while not automatic in all jurisdictions, is extremely likely to be permitted. To clarify, while this completion is not specifically a legal duty (e.g., specified by a special item of legislation), it is regarded (or can be argued to be) in most legal systems as a legitimate expectation of the “average, reasonable,” organization upon its employees or those mandated by the employer with the operation of the Command Center, and therefore admissible in most courts, on a similar basis to either Nurse’s Notes, or the notes created in a Police Officer’s memo book.

Incident Action Planning Process

The IAP is an essential document for the effective management of any type of major emergency situation. Without a plan, the Incident Manager will be doomed to managing the incident almost exclusively by reaction and will be unlikely to achieve a position of pro-active response. Such a process permits the Incident Manager to organize both issues requiring resolution and resources, create and test strategies, communicate those strategies to the other members of the Command Team, and begin to manage by objectives. Management by Objectives8 should be a central component of the IAP. An IAP formally documents incident goals, operational period objectives, and the response strategy defined by incident command during response planning,9 and the management of the incident itself can be seen as project, and therefore subject to the principles of Project Management, and an exercise in Management by Objectives.

The earliest stages of the IAP will probably exist nowhere other than in the mind of the Incident Manager. This reality ensures that action to resolve the incident begins to occur quickly, because until the intervention process begins, the incident itself will continue to grow and develop, and the situation is likely to continue to worsen, affecting more people and becoming more complex. No two IAPs will EVER be exactly alike, although many may be similar, at least in terms of subject headings. Each IAP will vary in content, according to both the nature and the needs of the incident which is occurring. There is, however, a process to this plan development, and a number of action steps which should occur.

Assembling the Team

The Incident Manager will make a decision to activate the Command Center and will issue direction for this to occur. This should include the summoning of the Command Team, and often, the actual assembly of the Command Center at a designated location. In most healthcare facilities, there should be a preidentified group of individuals, including both primary members and designated “back-ups” who make up the Command Team for the organization. Such individuals are usually selected, based upon training, skill sets, or roles within the organization. It should be noted, however, that such individuals may not be readily available 24 hours per day, and so, these positions may require filling on an “ad-hoc” basis by other staff members, until such time as the predesignated Team Members can arrive to relieve them. In such cases, these individuals will lack experience in this type of operation, and will require briefing, close support and supervision, and the use of tools such as the Job Action Sheet checklists,10 previously described, to support them.

Precisely who will be summoned can vary somewhat, based upon which Command-and-Control model the individual facility involved has incorporated into their Emergency Response Plan. In some Command-and-Control models (e.g., HEICS), all members of the Command Team are automatically activated, whereas in other (e.g., HECCS), only those Team Members who, in the opinion of the Incident Manager, are actually required to manage the incident effectively, will be summoned. Once the estimated time of arrival for each member has been identified, and time for the first Business Cycle Meeting can be determined and announced.

Establish Initial Business Cycle/Planning Meeting

The first meeting of the Command Team should occur at the predesignated time, with the Command Center fully assembled. The Incident Manager should be prepared to brief all of the Command Team regarding the current situation, its impacts, actual and expected, upon the facility, and any problems currently being encountered, as well as identifying any problems with a real potential for occurrence. Roles are confirmed, and individuals assigned to develop as much information as possible from within the responsibilities of their particular role (e.g., Liaison seeks information from the incident scene through emergency responders, Operations checks the current status of the Emergency Room, Logistics checks staffing and resources on hand), being prepared to contribute to a much more comprehensive assessment of the situation and its potential impacts on the facility at the next Business Cycle meeting. This first meeting is intended to get everyone in place, with an understanding of their roles and expectations, and an initial understanding of the incident. At this point in large incidents, the Business Cycle meetings will probably occur frequently (e.g., every 30 minutes), but this will be determined by the Incident Manager.

Developing Situational Awareness

The best Command Team in the world cannot begin to plan and execute the response to an emergency until they have a reasonably accurate evaluation of precisely what the emergency is, and how it is operating. The first operation period will be directed at the gathering and analysis of as much information as can be obtained. This information should include the type of incident and the precise circumstances of its occurrence in this case. Information should also include any likely impacts and secondary problems which can be foreseen. Command Team staff should reach out to local Emergency Management, and to the emergency response services (Police, Fire, EMS), in order to identify precise circumstances, estimated patient and casualty loads, recommended precautions and safety procedures.

To illustrate, a train has derailed near town. Is it a passenger train or a freight train? If the train is a passenger train, how many victims are on board? How severe are the injuries, and how many are deceased? Are there any secondary victims who were not actually on the train? Is this going to require a mass-casualty incident response? Are the victims all coming to this facility, or will they be distributed to a group of facilities? What triage classifications will we be receiving? If it is a freight train, are there any hazardous materials on board? What types? Have they been specifically identified? Are they leaking? Are the train crew injured? Are there any patients, either train crew or responders who will require decontamination? Where will this occur? Where is the train, relative to the facility? Which way is the wind blowing? Are any areas being evacuated?

Next, a relatively complete picture of the facility’s current status is also required. How many staff are currently on duty? Of what types? What are the current statuses of the Emergency Department, Operating Theaters, and Intensive Care? How many beds are currently available in the facility? How many patients could be discharged to provide space? Are there other facilities nearby, and what space do they have? Are they activating their Emergency Response Plans? Do we have ongoing contact arrangements in place with them? How will these arrangements work?

Analysis of the information gathered should be the next step. To continue with the example already described. Do we have sufficient staff to manage this incident already in place? What types of staff do we require? Why do we need them? How long will it take them to arrive here? Which currently offline services (e.g., Diagnostic Imaging, Laboratory, O.R.) do we need to reactivate? How many patients can we manage appropriately with the supplies that are currently on hand? For what items? Are we likely to be overwhelmed with new patients? With all of this information at hand, we are ready for the second Business Cycle meeting, which will focus upon developing a much more complete assessment of the incident itself, and of our likely role in the response to it. This will be used to formulate strategies for response to the impacts of the incident, to be implemented during the second Operational Period.

Definition of Management Strategy

Once the information collection and initial analysis have been completed, the Command Team can begin to formulate a formal Incident Management Strategy. How, in general terms, will the facility or the organization begin to respond to the event in question? This decision will ultimately be made by the Incident Manager, but with considerable consultation and input from all other members of the Command Team. At this point, it is realistic to begin to view the successful response to the effects of the incident as a project, and to begin to employ Project Management principles and skills. These will involve identifying the actual steps required to resolve the incident, and to also identify any preceding measures which are required in order to ensure their occurrence.

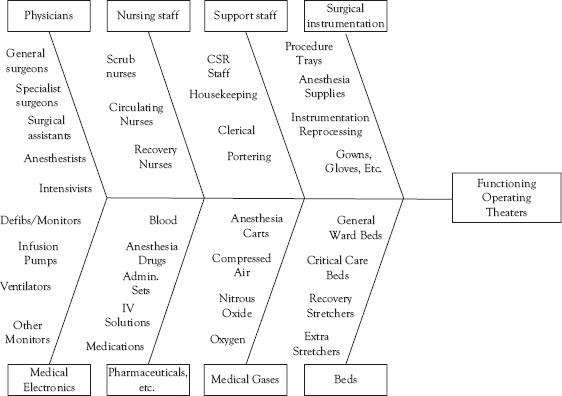

To illustrate, it is decided that the Operating Theaters will all be required to effectively manage the injuries, but it is currently 2 a.m., and these are currently dormant. This will require not only the activation of both surgeons and anesthetists but also nurses. The theaters are likely all ready for use (they are typically cleaned the night before to be ready for the first case each morning), but will require cleaning, following each case, and cleaning requires specially trained staff. Surgical instrumentation, medical gases, and medications will also be required; where are they kept and how do you access them at 2 a.m.? Finally, you will require additional nurses to staff the Recovery Area, a separate skill in its own right. Who will obtain each of these resources? How will it be obtained? How long will it take to get all of these resources in place?

What this example represents is a single management strategy; one of many that will be required in order to resolve the incident, and an entire list of tasks which will need to be performed, if that strategy is to function and become effective. It is not enough to simply announce that a given event must occur; it must be thought out in step-by-step detail, by either the Incident Manager or another member of the Command Team, if it is to become anything more than just an idea. The same is true for absolutely every strategy that the Command Team formulates; for unless the “loop is closed,” strategies are truly little more than ideas.

The entire response process should ultimately be committed to paper, or at least, to a computer diagram. Since what is being described previously represents a single strategy, requiring both cause and effect processes, it would probably benefit from the employment of what is known in Project Management as an Ishikawa,11 or “fishbone” diagram. This process starts with the required outcome; in this case, the activation of the Operating Theaters, and essentially, “reverse-engineers” the process leading to that outcome, identifying every essential step, so that it can be both assigned to someone as a task, and then monitored for completion. This technique can be applied by the Incident Manager and the Command Team to the entire IAP, or to each of its components, as required, and can provide a “roadmap” for both the subsequent actions of the Command Center, and the ultimate resolution of the incident.

Identifying Goals, Tactics, and Tasks

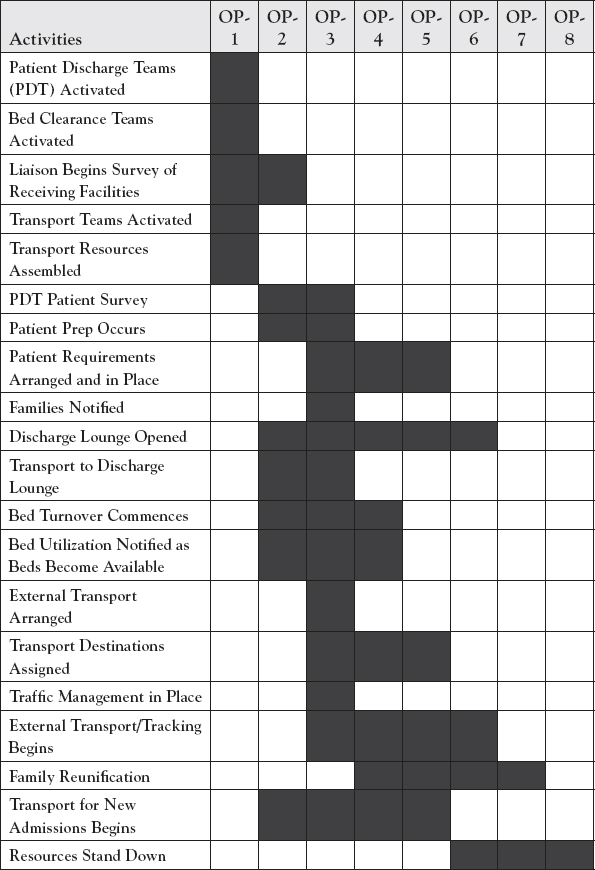

For the purposes of this discussion, it is appropriate to define goals as very large scale accomplishments directed at the response to or resolution of the incident. For example, the development of sufficient in-patient bed space to treat all of the victims of a mass casualty incident who require admission would represent a goal. A tactic might be described as a somewhat smaller scale event, one of several required to achieve a goal, but still significant in terms of resource usage. In the same context, a tactic might be the successful discharge of all in-patients for whom discharge is safe and appropriate. A task may be assigned a smaller scale event; one which is directed at supporting the completion of a tactic, or simply a requirement of the response to the crisis. To illustrate, in this context, a task might be the assembly and staffing of a “discharge lounge”; a holding area to which discharged patients are sent to await transportation, in order to clear the beds.

Figure 5.1 The Ishikawa diagram. A “fishbone” diagram for after-hours activation of Operating Theaters. These steps are by no means exhaustive

For planning purposes, the Incident Manager may employ the same Ishikawa diagram process previously described to identify, plot out, and assign each of the steps in the bed clearance process. In such a diagram, the goal would be the end product. Each of the arms would represent a tactic which is required in order to achieve the goal. The tasks are represented as incremental steps along each tactical “arm.” In this manner, a template is developed for the achievement of specific major goals.

It is appropriate to point out here that it is entirely possible to complete much of this effort in advance, in some circumstances. This is particularly true for elements of the greater response to an emergency which are most likely to occur. These might include, but are by no means limited to:

• Preparation of the ER for a Mass Casualty Event

• Assembly of Decontamination Equipment

• Internal Surge Management Plan

• After-hours Activation of the Operating Theaters

• Emergency Bed Clearance

• Activation of the Command Center

Each of these “goals” can be developed in advance by the Emergency Manager, using the same type of Ishikawa diagram, and then developed into actual procedures. Once the TEWT exercise for each has identified operating locations and resource requirements, these procedures can be developed, using a similar type of checklist to the Job Action Sheets, which should be in use in the Command Center. Such checklists could then be added to the Emergency Response Plan as Annexes and tested periodically as exercises or drills. This approach turns the infrequently performed procedures involved into a “standardized work” approach, such as those used in both Six Sigma and Lean, further adding to the effectiveness of the overall Emergency Response Plan. It also accelerates the facility’s ability to respond to a crisis, since, with all of the conversion steps identified in advance and transformed into simple procedures, the Incident Manager and the Command Team can focus on “when” to take a step, and not have to waste time deciding “how” to do it!

Setting Goals, Objectives, and Timelines

Once the actual measures that are required in order to achieve the resolution of the incident, it is reasonable to organize these into the IAP. It must be remembered that even in emergency response, everything doesn’t happen at once! The goals and objectives must be placed in some type of rational order, and those goals and objectives with associated interdependencies (e.g., you can’t clear the ER until in-patient beds are made available) must be identified and placed in the correct order. Some estimate for the actual completion time for each step will also be required. The Ishikawa Diagrams for specific processes should be a part of the planning process; however, this process will also benefit from the use of another tool, the timeline. Once again, there are tools from mainstream Project Management, such as GANTT Charts, which can help to organize the entire project, the individual steps involved, and their interdependencies.

Setting Operational Periods

Once all of this information is gathered, it becomes practical to attempt to manage the incident in smaller time segments, through the use of the goals and objectives identified, and the timelines required for the completion of each. By assigning tasks with reasonable completion times, it becomes possible to actual measure and evaluation progress in the facility’s response to the crisis. With a sense of what should be completed and when, the Incident Manager can identify specific intervals at which monitoring tasks for completion are appropriate. The time between such intervals may be identified as Operational Periods. Such tools also make reporting more manageable and understandable. To illustrate, as a statement of objectives in a report to senior management, it would be appropriate to say “during the next Operational Period, it is our intention to finally resolve the problem with…” The Operational Periods are likely to start out with a fixed duration but are likely to be changed at the direction of the Incident Manager, as changes to the incident and its response dictate.

Establishing the Business Cycle/Planning Meeting Timetable

With all of the individual tasks, tactics, and goals, their probable timelines and Operational Periods identified, it becomes possible to create a more organized and rational schedule for the meetings of the Command Team. These should be driven by the Operational Periods and will become a tool which brings all of the members of the Command Team together to report, identify progress, identify problems, engage in problem-solving discussions, and receive new assignments from the Incident Manager. These meetings also become an essential tool for the Incident Manager, for use in measuring both progress and performance, and for the early identification and resolution of new problems. In using this method, both the Incident Manager and the Command Team are constantly provided with the best possible information with which to make decisions and plan further measures, if required.

The timing of such meetings, as previously stated, is usually driven by the length of the Operational Periods, which are, in turn, driven largely by the needs of the incident and the facility’s response to it. To illustrate, in the earliest stages of a mass casualty incident, Business Cycle Meetings may need to occur every thirty minutes, whereas, in a pandemic scenario, the Business Cycle Meetings might be simply daily occurrences. Such timing is variable, and may change as needs change, so that as the same mass casualty incident winds down, for example, the response is organized and effective, and with less problems requiring resolution, the Operational Periods will simply grow longer, and the Business Cycle schedule will be adjusted accordingly. In all cases, the scheduling and duration of the Business Cycle meetings are at the discretion of the Incident Manager.

Monitoring for Completion

Each discreet task and strategy will require monitoring for completion by the Incident Manager. When this measure does not occur, it is common for tasks to be set to one side due to conflicting priorities, and never returned to. When tasks are interdependent upon one another as components of a larger strategy, the effect of uncompleted tasks quickly becomes cumulative, and may, in fact, substantially degrade the entire response to the crisis, if the wrong tasks are missed, or a particular strategy fails. In order to monitor so many individual tasks and strategies, the Incident Manager will require help … attempting to keep track of some many things at once in your head is a recipe for disaster, and any response process which is not documented in detail may be difficult to explain and defend, after the fact. Fortunately, there are, once again, extremely useful tools which can be borrowed by the Incident Manager from mainstream business concepts, which lend themselves extremely well to this task.

Using Mainstream Business Tools

Project Management

This process can be highly useful for most aspects of emergency management and guiding the facility through a crisis of any sort is no exception. It is entirely appropriate to view any major crisis in a healthcare facility as a complex challenge, with potentially dozens of interdependent tasks and measures required, and their successful completion is important. There is no need for the type of reactive management which has been common in most areas of emergency management, including that practiced in healthcare. A pro-active approach is typically far more successful, and certainly far less stressful for both the Incident Manager and the Command Team.

Many researchers tend to view crisis management as a necessary evil of organizational management.12 However, by treating the resolution of the crisis as a “project” and applying the processes of project management to its analysis, organization of tasks, monitoring of tasks, and resolution of the incident, most issues will remain better organized, less will be forgotten or missed, the timelines for resolution are likely to be shortened, and the outcome is more likely to be successful. Interestingly, just as with the Command-and-Control models being proposed here, the majority of the clinical side of healthcare already works this way; they just don’t call it project management! Think of a clinical emergency. A team of people assembles, they perform those interventions which are urgently required immediately, they then analyze what is happening, formulate a strategy for fixing it, set priorities for assessments, procedures, and so on, and, if the “project” is successful, the patient survives and recovers.

Many industries continually manage complex projects. Project Management is intended to identify and predict as many potential problems as possible, and to “plan, organize, and control activities,”13 so that the project is completed successfully, despite potential risks which may have been present. Project Management is in use in a variety of sectors, including civil engineering and manufacturing, and there is no valid reason why this approach to structured problem solving and resource application cannot work successfully in emergency management for healthcare settings. While there is no shortage of “how to” books about this process, both in-person and online training and certification are also available from a variety of reputable sources, including both consulting firms14 and universities.15 As a result, most healthcare facilities would greatly benefit from having both an Emergency Manager and the group who are preselected for the Incident Manager role, to be formally trained in Project Management.

Ishikawa Diagrams

Also called “fishbone” or “cause and effect” diagrams were originally designed for the analysis of errors which had occurred in manufacturing processes. In a less conventional approach, this tool may also be used by the Incident Manager, or the Planning Lead, to map both the processes or tasks required to implement a specific strategy and also the resources that are required to support each process or task. Once the tasks and processes, and their required supports are identified, it becomes much easier to ensure that nothing has been overlooked, and to estimate the amount of time required in order to implement each, as well as for the implementation of the entire strategy which they describe. As such, the information generated can be used by the Incident Manager to develop and to drive the Business Cycle process, by helping to identify both the strategies required to support a particular response tactic, and also those resources which will be needed in order to support each tactic.

While such techniques can and should be valuable advance planning tools for the Emergency Manager developing response steps ahead of any emergency, they can also be an equally valuable tool for use by the Incident Manager in getting the response to the emergency properly organized, or for the analysis of some error or other issue in the response to the emergency. As such, this tool should be a part of the “toolkit” created by the Emergency Manager for use by the Incident Manager during any emergency. Such tools may be crude, blank templates, printed in advance and included in the toolkit, or may be computerized, using the basic software which should already be available in the Command Center, such as Microsoft Office. Excellent templates for such diagrams are readily available to download for free from various sources on the Internet,16 and the student is encouraged to access these and practice using them.

Figure 5.2 Emergency bed clearance. A “fishbone” diagram outlining resource requirements for an Emergency Bed Clearance Plan. The items are by no means exhaustive

Identifying and Implementing Support Tasks

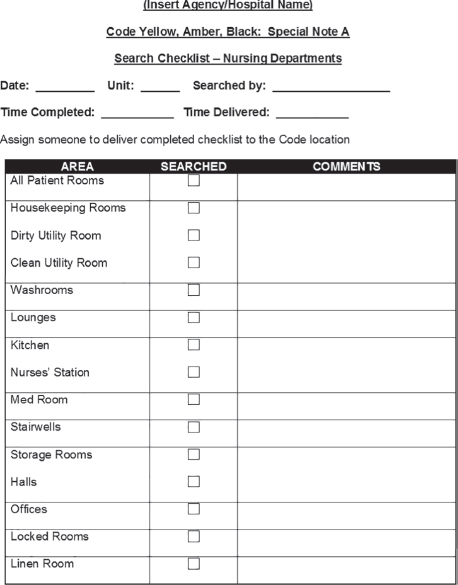

The Ishikawa Diagram technique can help to provide the Incident Manager with lists of support requirements, whether these involve workspaces in which particular processes can occur, general or specialist staff, and the physical resources which they will require with which to perform the task in question. Such sites will require other support resources as well, including maintenance items, such as housekeeping, security, and resupply of expendable resources. With a complete picture of what is involved in the activation of a specific task needed to support a given strategy, that task can then be assigned for completion in support of the strategy, through the Command Center’s Business Cycle meetings. The appropriate Ishikawa Diagram can be used to facilitate discussion, problem-solving and task assignment, as a part of the Business Cycle process. Much of this development can be effectively performed in advance, and formalized, using the Checklist process previously described. This balances the need to ensure that a task is performed thoroughly and correctly, without improvisation, against the need to expedite response to the crisis. Rather than having to provide the person who will implement the task in question with detailed, step-by-step verbal instructions, they can be simply handed the appropriate checklist and told to follow the steps and report back if there is a problem. Simply directing someone to perform a specific task and hoping that they “get it right” is rarely a formula for success.

Figure 5.3 A simple procedural checklist. A Checklist for the Search of a single Nursing Unit for a missing person or a suspicious package. Such tools can be used for many purposes and should be developed and tested in advance of any emergency

GANTT Charts

A Gantt chart, named for its creator, Henry Gantt, can be a useful tool for the Incident Manager to use for tracking both progress and timeliness of completion for both tasks and strategies. The Gantt chart displays activities such as tasks and strategies as blocks or bars over time.17 As such, it displays the interconnectedness of multiple tasks with a project and can be used to display all tasks and strategies concurrently over time. Taking all of the required tasks and strategies, and their estimated timelines, and plotting these on a Gantt chart may help the Incident Manager to identify elements of interconnectivity that were not initially apparent and may also help to identify potential issues requiring resolution, prior to their actual occurrence.

Such a tool can tremendously facilitate discussion during the Business Cycle by simply displaying it on a whiteboard in the Command Center and referring to it during the meeting. This tool can contribute greatly to the development of proactivity in the management of whatever crisis is occurring. It can be used for both the management and oversight of specific elements of strategy, or it may be used to display all elements of the overall crisis response. Excellent templates for the creation of Gantt charts are readily available to the Emergency Manager from a variety of sources, including free online downloads.18 Such charts can also be created using simple graph paper, or by using the Insert Table function in any version of Microsoft Word. These can be added to the “toolbox” of the Incident Manager from such sources by the Emergency Manager.

Measuring and Monitoring Progress

The use of the Gantt chart can provide the Incident Manager with an important visual reference source. Through the creation of specific timelines for various measures and a process for tracking these measures, the Incident Manager is provided with an “at-a-glance” information source which permits the monitoring of completion of specific measures, as well as whether or not that completion is occurring in a timely fashion. Delays are identified, and can be acted upon, in the very next Business Cycle meeting, thereby ensuring that the “loop”’ is closed, and no measure which has been implemented is subsequently overlooked, resulting in problems in the response to the crisis.

Monitoring for Effectiveness

The Emergency Manager in a healthcare setting should understand that simply monitoring for completion and timeliness is insufficient. It is absolutely essential that the result of the assigned task also be monitored. If the assigned task fails to address the issue it was intended for, it must be subjected to analysis, problem-solving, and revision, or the effort has been wasted. This analysis and problem-solving are essential elements of the Command Center Business Cycle; it isn’t just about what happened and when. An effective Business Cycle not only assigns response tasks and records events but it must also continue to analyze the event itself and the response tasks assigned to address it, in order to drive a process which generates both pro-activity and positive results.

Figure 5.4 A simple Gantt chart outlining the procedure and timelines for the implementation of the previously shown Emergency Bed Clearance Plan. The steps are by no means exhaustive

The tools which have been previously discussed can be used as a part of the Business Cycle to organize tactics and assign tasks, to simplify and standardize emergency instructions, and can also be used to analyze results. They employ some of the best practices of Six Sigma and Lean for Healthcare to any emergency response, in order to make the Business Cycle a highly effective method for driving the resolution of the emergency with a process of continuous quality improvement. There was a time when the average Command Team would essentially sit in a room and respond to each bad thing as it happened. Through the efforts of the knowledgeable Emergency Manager to introduce these key business practices to the Command Center Business Cycle through advance preparation and Incident Manager training, that time has passed.

Documentation

The documentation of the response to whatever crisis has occurred is an essential part of the responsibilities associated with the Business Cycle and the Command Center. It has been said that “it is not enough to do the right thing … one must be SEEN to do the right thing!” While this is certainly a true adage, in a healthcare setting, it is insufficient. In fact, one must not only be SEEN to do the right thing, but one must also be able to demonstrate this fact consistently and comprehensively, on paper, after the fact! Just as in every other aspect of the provision of healthcare, emergency management has an expectation of consistent and professional documentation, and this occurs in an environment in which the attitude in any type of review which occurs after the fact is likely to be “if it isn’t written down … it didn’t happen!”

It is for these reasons that the Incident Manager and the Command Team have a Scribe attached to their operation. It is this individual’s job to assist the Incident Manager in creating the most consistent and comprehensive documentation possible of the crisis response operation, at the time of occurrence, and with a duty of completion. This process helps to ensure that the information generated by the entire response, including each decision and step taken, how it was done and why it was necessary. These facts are necessary for later review, learning and improvement, and may actually be required in order to defend both the Incident Manager and the healthcare facility against assertions of inadequate or inappropriate responses in managing whatever crisis has occurred. Such documentation can also be essential in assisting a healthcare facility in achieving the recovery of some or all response costs from both insurance carriers or various levels of government, depending upon the type of administrative setting it is operating in.

It is equally important to standardize the process of documentation itself. In the rest of healthcare, and particularly in the clinical sector, absolutely everything done is documented, and it is done in a standardized format. Whichever physician or nurse has provided some service to a patient, it will be documented in the same manner on an identical form which is expressly designed for the purpose. There is a duty of completion, and virtually all of such forms are admissible, in fact will probably be subpoenaed, in any legal proceedings which may arise from the care of the patient. There is no reason why the expectation for emergency management in the healthcare setting should be any different.

The Emergency Manager who is operating in a healthcare setting must ensure in advance that there is not only an Emergency Response Plan, but that the Plan contains a package of standardized, easy to find and easy to use documents, for use in recording both events and decisions from the Business Cycle meetings, the formulation of strategies and the assignment of tasks, the receipt and filling of requests for both information and resources, and the outward and upward reporting of status and results, both during the incident and after the fact. Such documents must be readily available, and easy to use, and MUST be completed at the time of occurrence, since their later admissibility in an external review or a court proceeding may be crucial to defending the staff and the facility. The documentation of the Business Cycle is as important as the meetings themselves!

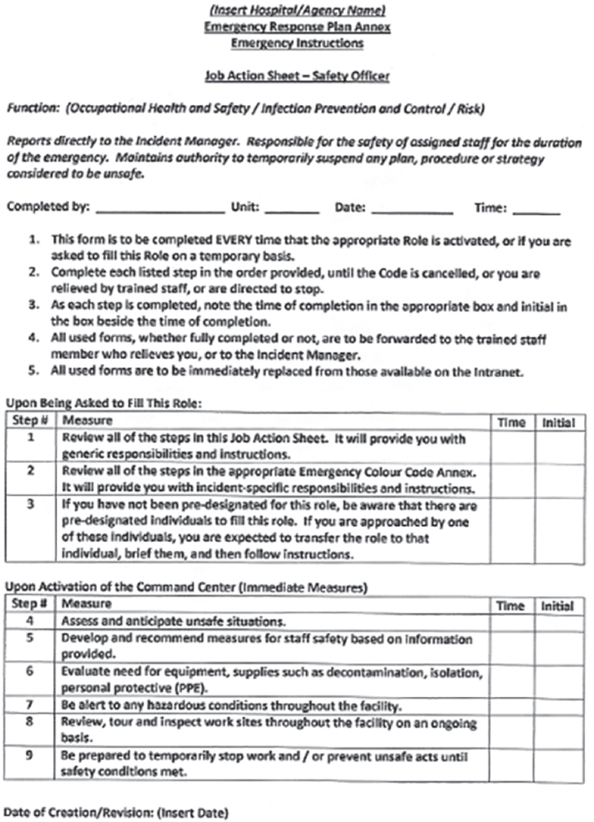

These sheets provide consistent and standardized instructions to all essential personnel who are functioning in the Command Center and may be extended outward by the Emergency Manager to other essential functions. Each Job Action Sheet19 is specific to the assigned role, and will provide clear, step-by-step instructions to the user. They are not comprehensive, and cannot be, due to the fact that each emergency event is different. They can, however, provide a set of standardized measures which MUST be taken by the incumbent in each role, regardless of the type of emergency which is operating. The steps are written in clear and unequivocal language; they are orders, not suggestions, and they are sequential. They may also be differentiated as Immediate, Intermediate, and Long-term actions. On a well-designed Job Action Sheet, the user will, as each measure is completed, note the time of completion and initial the entry. Once each Job Action Sheet is completed, it should be given to the Incident Manager for inclusion in the permanent record of the Command Center.

Such tools function as a reminder for those who are experienced in Command Center operations and their respective roles, and its directions will serve as a “roadmap” of sorts, for the inexperienced user. They are a tremendous tool for consistency in mounting the operation of the Command Center and the Business Cycle and a labor-saving device for the Incident Manager. If a given Job Action Sheet contains 40 step-by-step instructions for the user, those represent 40 elements of work direction that the Incident Manager will not have to remember, provide, or monitor for completion. Multiplied across the entire Command Center Team, the labor savings for the Incident Manager, and the amount of consistency and standardization generated are truly immense! The use of this tool can be extended to an entire range of emergency response functions, including other key roles, or the development of other key response resources (e.g., assembly of the Command Center, assembly of a Triage Area, and so on). In addition, the use of such tools, taken collectively, will provide a comprehensive, step-by-step chronology of every measure taken to prepare for the response to the emergency, and the duty of completion makes that information fully admissible in many court proceedings.

Figure 5.5 The Job Action Sheet. A typical Job Action Sheet for the key role of Safety Officer. Note the clear step-by-step instructions and the “standardized work” approach. Developed in advance, such tools can save tremendous amounts of time and work during the crisis response

Event Log

The Event Log is used to document all activities, problems, requests, decisions, strategies, and assignments associated with the response to the emergency event. It should be commenced as soon as practical following the start of the emergency, and certainly upon the activation of the Command Center. It can be used to document the arrival and departure of staff, changes of shift and responsibilities, major occurrences, and the minutes of each Business Cycle meeting. It should provide a straightforward, chronological narrative of the entire response to the emergency, in detail. Each new page used should be numbered sequentially, to provide for continuity, and to eliminate any potential for “missing” entries. The Event Log should also record the creation and completion/return of every other document used as part of the Command Center and Business Cycle processes. The person reporting will normally be either the Incident Manager or the Scribe, but in all cases, whoever is reporting should be clearly identified, typically with initials or a signature, and the time of each entry in the Event Log should be noted, as well.

The process of completion is not unlike the Nurse’s Notes format, which is typically used by clinicians, and the duty of completion of the Event Log provides some degree of assurance that it will probably be admissible in subsequent inquiries or legal actions, following the conclusion of the emergency. By recording the creation and the completion/return of all other documents in the Event Log should also provide sufficient “connection” to assure their admissibility, as well. The Event Log will clearly identify exactly who did what, and when. It will also document all decisions, and the rationale for specific action and management choices by the Incident Manager and other members of the Command Team. The document provides comprehensive overview of all aspects of the Business Cycle of the Command Center and may also help to facilitate the upward and outward reporting functions required by the Incident Manager. Blank copies of the basic document should be readily available within the facility’s Command Center assembly kit.

Resource/Information Requests

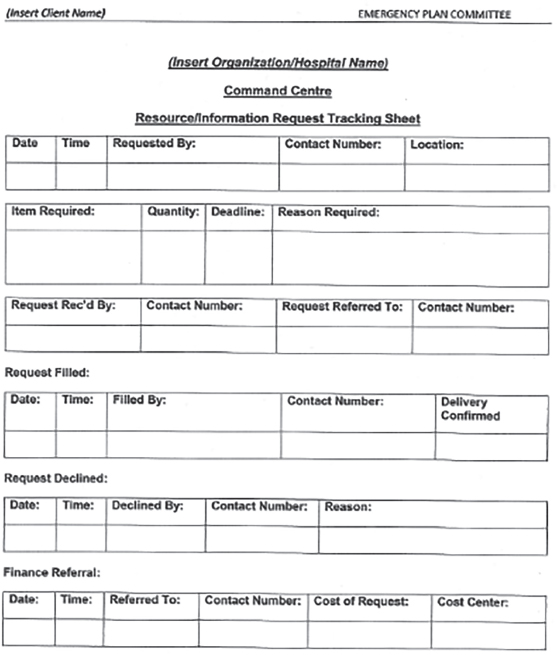

The information flow within a Command Center can be confusing at times, even with a well-organized and well-run Business Cycle. The requests for information and resources are likely to flow to the Command Center from various sources and will not always be received by the individual who will ultimately be responsible for the filling of the request. Additionally, a request may initially seem complete, but may ultimately require follow up for additional information or clarification on what is actually being specifically requested.

Figure 5.6 The Event Log Sheet. A fairly typical blank Event Log sheet. Note the timing required for each entry, and the provision for the sequential numbering of the sheets which will make up the total Log document

In a crisis management environment, it is surprisingly easy for requests to be set down somewhere, and then completely forgotten about, as the competing and conflicting demands of the incident intervene. If that is not enough, a great many of the requests received may have a monetary value associated with them, as resources may require purchase, or additional staff will definitely require payment, and so, documentation from beginning to end of any request with any economic impact is definitely required, particularly in environments in which healthcare facilities hope to be reimbursed for unscheduled emergency response expenditures by either insurers or various levels of government, depending upon the care model which is operating. Any effective Command Center, and its Business Cycle, require an information and request management system in which absolutely everything is tracked, and which “closes the loop” on the filling of requests of all types, as efficiently as possible.

The Information/Resource Request Tracking Form can provide a useful tool for the filling of all of these requirements. The requestor calls in to the Command Center, specifies what they need, and information is gathered on when the request was received, by whom, the identity and contact information of the requestor, where they are located, what they need, by when, and why. The information is then recorded and “triaged” to the individual who will be responsible for filling the request, and that individual’s identity, role, location, and contact information, the time of assignment and the time of expected completion will also be recorded.

The request will then be entered into the Event Log, and also into the request tracking process. While many systems may rely solely on paper, the better-designed Command Centers will typically employ a dedicated whiteboard to the purpose of request tracking. In such cases, the information on the form is entered on the whiteboard, where it will remain until the request, whatever it may be, has been filled, or until a decision has been made not to fill the request for various reasons, and this information has been returned to the requestor. Command Center staff, and the Incident Manager in particular, can then use the whiteboard to monitor each request for timely completion, and to ensure that nothing is overlooked.

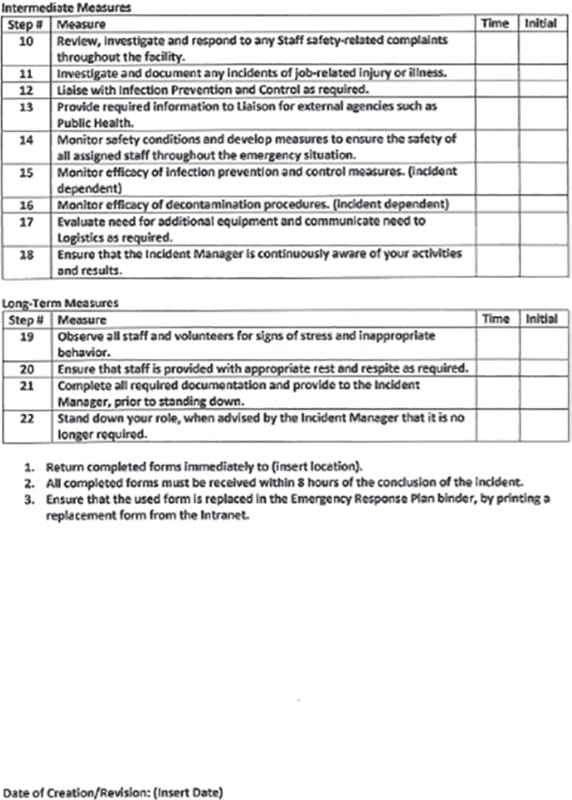

Situation Report20

This document is a formal periodic report of the progress being made in responding to the incident, as well as any problems encountered. This report is typically created by the Incident Manager, supported by the Scribe, and, in some models, by the Planning function. The intent is to provide for the type of upward reporting required to keep senior management aware of what is occurring in the emergency response, and also to provide outward reporting to other agencies involved in the response, in order to supplement the efforts of the Liaison function in ensuring that all responders and various levels of government have appropriate access to the required information. Such reports are typically created and issued at the conclusion of each Business Cycle meeting, when the organizations’ information is the most current, and when resource and support needed requests can be fulfilled in as timely a manner as possible.

Figure 5.7 Information/Resource Request Form. A typical Information/ Resource Request Tracking Form. Such documents contribute greatly to the monitoring and closing of requests of various types and should be a mandatory part of every Command Center toolkit

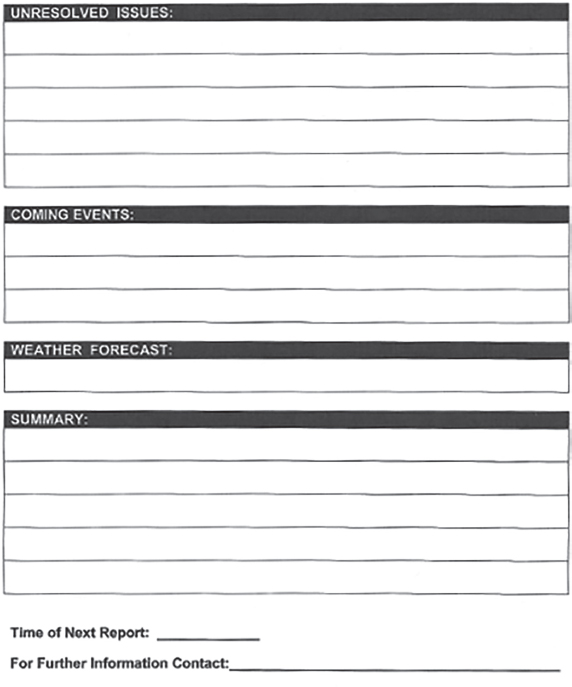

Figure 5.8 The Situation Report. A typical Situation Report form. Note the different headings provided to ensure consistent information and progress reporting. Such blank forms should be a part of every Command Center toolkit

Deciding to Stand Down

In any emergency involving a healthcare facility, the decision to stand down from the emergency response is typically made collectively, and not unilaterally. There are many aspects of the response in which the decision to stand down can potentially affect clinical outcomes, and so, input from all sources, with the final decision being made by senior management, is the most likely scenario. That being said, the information and tracking generated by the Command Center staff and by the Business Cycle itself are likely to play a key role. With the Command Center tracking all resource requests and response activities through the Business Cycle, it is likely that this information will provide the first cues that the need for special response to what is happening is winding down.

It is likely that the first sign will be a decrease in information or resource requests, or that such requests begin to change in nature, from the gathering of information and resources to manage the crisis, to the gathering of information and resources on managing a patient load which has become more “static.” Care is a continuum, and such information as the fact that EMS at the scene is advising that all victims have been transported, or the temporary treatment area is no longer required, or that the Emergency Department is re-stocking, after being overwhelmed, or that the current backlog of patients in the process are waiting for the Operating Theaters or stuck in Recovery, awaiting in-patient beds.

While such changes will not necessarily generate a complete stand-down, it is likely to result in discussions during Business Cycle meetings about phasing out “front-end” crisis services, such as an overstaffed Emergency Department or temporary treatment areas, in order to re-focus the existing resources on assisting other services, further along the continuum of care, which are still overwhelmed. Finally, the surge in demand for services will reach the point at which crisis response is no longer required, and the Command Center and its Business Cycle can focus on the development of activities which are directed at permitting the entire organization to begin an actual recovery from the crisis.

It is not until the Business Cycle relates that most of the recovery activities are in place, with staff rotated and rested and re-supply of all areas occurring, that the time has probably come to stand down the emergency response and return to normal operations. At that point, the Incident Manager will stage a final Business Cycle meeting, receiving final reports, collecting all documentation, and thanking and releasing all Command Team members and support staff. A final Situation Report will be issued to all outside agencies which have received updates throughout the emergency response. The facility will be advised that the emergency response has ended, and that normal operations have resumed. The Command Center will be refurbished and re-stocked, then disassembled and repacked, ready for the next emergency. The Incident Manager will then close out the Event Log and begin the next steps in the recovery process.

With the Command Center closed down and returned to storage, the Incident Manager must begin to analyze what has happened. This will include an early and comprehensive debriefing of all staff who participated in the emergency, either in the Command Center or on the “front lines,” in order to gather as much information from them regarding what went well and where opportunities for improvement exist. The next stage is the detailed review and analysis of all of the documentation generated by the emergency, including the Job Action Sheets, the Event Log, Information/ Resource Request Tracking forms, and the Situation Reports which were issued. With this information in hand, the Incident Manager is ready to begin to write the After-Action Report.

After-Action Report

This report is generated at the conclusion of the incident and is normally crafted by the Incident Manager(s), usually assisted by the Scribe(s), the Emergency Manager, and any personnel assigned to the Planning function. It is intended to provide a clear and succinct description of the emergency which occurred, the impacts on the healthcare facility, and the strategies, tactics, and tasks required to permit the appropriate response of the facility to the situation. It should identify problems encountered and how these were managed, along with specific recommendations for the improvement of future responses. The After-Action Report should also recognize and report all successes and should acknowledge and thank those responsible for these. Finally, with the assistance of the Finance function, it should provide a summary of costs, describing in detail the expenses incurred as a result of the response, in case there is any possibility of financial compensation from outside sources.

This document, when completed, will be sent to the senior management team of the facility, ideally within seven working days of the conclusion of the incident. It can also be used for insurance claims and for future training endeavors. Finally, a copy of the After-Action Report should be packaged, along with ALL of the documentation generated by the incident response, including the Job Action Sheets, the Event Log, Information/Resource Request Tracking Sheets, and the Situation Reports, and should be sealed and delivered to the appropriate location within the organization for long-term, secure storage, against future need. This location will vary by organization, but is most likely to be the Legal Department, Risk Management, or the Emergency Manager.

Conclusion

The response to a crisis is NOT “business as usual,” even in a healthcare facility, where the management of crises are a part of the everyday job description. If normal procedures and methods worked in emergency response, there would be no emergency to respond to. The Command Center and the Business Cycle provide an essential construct in which to engage in “outside the box” thinking and a unique, collaborative, and creative problem-solving process with which to manage the response to an emergency of any type. The “heart and soul” of this process is the Business Cycle. It permits a team (or teams) of people, who may not even work closely on a daily basis, to work collaboratively, in an atmosphere of cooperation and trust, to find strategies, tactics, and tasks with which to effectively manage an abnormal incident, and then to successfully implement these measures, in order to effectively guide the organization to the other side of the emergency event as effectively as possible.

The skills and information described in this chapter are essential knowledge for any Emergency Manager working in a healthcare setting. They provide a “toolkit” of both documents and mainstream business management techniques and methods drawn from such models as Project Management, Lean for Healthcare, Six Sigma, and Continuous Quality Improvement. Such powerful tools will nearly always prove to be useful to the practice of emergency management within the healthcare setting, whether in the day-to-day planning, education and training, or mitigation processes, or when an actual major emergency challenges both the Emergency Manager and the facility itself.

Student Projects

Student Project #1

The student will select a single, discreet, major task which may be required in order for the facility to successfully respond to a major emergency (e.g., assembly of decontamination equipment). Talk to those responsible for the equipment, establish what the current procedures are, and identify any problems which have already been identified. Next, conduct research and identify how this procedure is managed in other healthcare facilities elsewhere, as well as any problems which other facilities have encountered. Next, create an Ishikawa (fishbone) diagram, identifying all of the required steps required to successfully complete the procedure. Now create a step-by-step checklist for the completion of the procedure you are studying and test it if you can. Finally, create a report recommending the adoption of the procedure which you have created. Ensure that major points are accurate and factual, and are appropriately cited and referenced, in order to demonstrate that the appropriate research has occurred.

Student Project #2

The student will develop a Project Plan for the creation of a new Document Package for the Command Center of their facility. This Project Plan should include both an Ishikawa diagram and a GANTT chart for the project. The student will conduct research in order to determine how Command Center documentation occurs at other healthcare facilities. The student will then create a blank template for each type of Command Center document which they feel is required. Finally, the student will create a report recommending and arguing for the adoption of the package of blank Command Center documents which they have created, and for their adoption into the facility’s Emergency Response Plan. Ensure that major points are accurate and factual, and are appropriately cited and referenced, in order to demonstrate that the appropriate research has occurred.

Test Your Knowledge

Take your time. Read each question carefully and select the MOST CORRECT answer for each. The correct answers appear at the end of the section. If you score less than 80 percent (eight correct answers) you should re-read this chapter.

1. A documented, structured process by which those who are tasked with major roles will meet, in order to exchange and analyze information, is called:

(a) Operational Period

(b) Goals and Objectives Meeting

(c) Situation Report

(d) Business Cycle Meeting

2. An essential document for the effective management of any type of major emergency situation is called the:

(a) Incident Action Plan

(b) Project Plan

(c) Situation Report

(d) Event Log

3. A planning tool which “reverse-engineers” the process leading to the completion of a major response tactic, identifying every essential step, so that it can be both assigned to someone as a task, and then monitored for completion, is called:

(a) Project Plan

(b) Ishikawa or “Fishbone” Diagram

(c) GANTT Chart

(d) PERT Chart

4. Once an essential element, such as a Command Center, has been created to aid in the facility’s response to a crisis, its activation may be both formalized and made easier through the development of:

(a) A Step-by-Step Checklist

(b) An Ishikawa Diagram

(d) Both (b) and (c)

5. The timing and the duration of any Command Center Business Cycle meeting is normally determined by:

(a) Corporate Policy

(b) The Needs of the Incident

(c) Decisions by the Incident Manager

(d) Both (b) and (c)

6. A formal periodic report of the progress being made in responding to the incident, as well as any problems encountered, is called:

(a) A Situation Report

(b) An After-Action Report

(c) A Job Action Sheet

(d) An Event Log

7. In order to ensure that documents associated with the Emergency Response Plan are used by staff during the response to any crisis, they must be:

(a) Easy to Understand

(b) Easy to Find

(c) Easy to Use

(d) All of the Above

8. One of the major purposes of the Business Cycle is to drive the response to the emergency through:

(a) The Use of Best Practices

(b) A Cycle of Continuous Quality Improvement

(c) The Use of Standard Operating Procedures

(d) The Use of Clinical Standards of Practice

9. In any crisis involving a healthcare setting, the decision to stand down is likely to occur jointly, involving the Command Center and:

(a) The Emergency Department

(b) The Legal Department

(c) The Senior Management Team

(d) Risk Management

10. An essential planning tool which can be used to illustrate the timing, duration, and interconnectivity between the tasks in a given response strategy is called a:

(a) PERT Chart

(b) Job Action Sheet

(c) GANTT Chart

(d) “Cause and Effect” Diagram

Answers

1. (d) 2. (a) 3. (b) 4. (a) 5. (d)

6. (a) 7. (d) 8. (b) 9. (c) 10. (c)

Additional Reading

The author recommends the following exceptionally good titles and websites as supplemental readings, which will help to enhance the student’s knowledge of those topics, or provide free access to useful tools and methods which are covered in this chapter:

Canton LG. 2007. Emergency Management: Concepts and Strategies for Effective Programs, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publishing, ISBN: 978-0470119754 Fishbone Cause and Effect Diagram, Template.net Website, www.template.net/business/word-templates/fishbone-diagram-template/ (accessed January 07, 2016).

Free Gantt Chart Template, Office Timeline Website, www.officetimeline.com/timeline-templates/gantt-chart-download (accessed January 06, 2016).

Public Health Emergency. 2012. Medical Surge Capacity and Capability Handbook, United States Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, .pdf document, www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/mscc/handbook/Pages/default.aspx (accessed January 02, 2016).

Shirley D. 2011. Project Management for Healthcare, Boca Raton FL: CRC Press, ISBN: 978-1439819531