Introduction

In acute care facilities, the demand for service, if not consistent, is generally somewhat predictable. While, under normal circumstances, forecasts of patient counts are possible, due to the somewhat erratic nature of human activity, only general trends can truly be predicted. Healthcare facilities typically rely on such predictions for planning the majority of their operations. Staffing, bed availability, surgical and other types of acute care availability, the availability of all types of supplies, and even operating hours within various internal services are based upon such planning assumptions. Healthcare facilities are designed to be cost-effective, which means that they operate at or near full capacity the majority of the time. Given issues such as fiscal constraint, many actually successfully operate beyond their designed capacity, in some cases, on a regular basis. When this fragile balance is disrupted by a sudden and unanticipated increase in demand (surge) for services, the challenges to successfully maintain high-quality services are significant and must be addressed.

This chapter will focus on the management of unexpected surges in the demand for services, due to disaster events. The concept of “surge capacity,”1 the ability to successfully and effectively cope with greater numbers of patients than the facility was intended to cope with, will be examined, along with the development of strategies for the exploitation of surge capacity. Also explored will be the concept of “surge capability”2; the ability to use existing resources differently, in order to provide an expanded scope of practice and care to a greater than normal number of patients. These paired concepts, and the practices associated with them, are essential to the successful management of any mass casualty incident, or other incident which generates expanded demands for service. As a result, the Emergency Manager must be familiar with both the concepts and their operation, in order to be able to effectively plan in advance for their use, when required.

Learning Objectives

Upon the conclusion of this chapter, the student will understand the causes of surges in the predicted demands for services within healthcare facilities, and their causes. The student will be able to describe the process of surge capacity, and the techniques for its successful use in a healthcare facility. The student will also be able to describe the process of surge capability, and the techniques for its successful implementation. Finally, the student will understand how such processes are created, and the advance planning and implementation requirements for the successful development of each.

Surge Capacity

The American College of Emergency Physicians defines surge capacity as a measurable representation of ability to manage a sudden influx of patients.3 Surge capacity may also be described as a measure of the ability of a hospital or clinical care system to rapidly adjust to caring for a sudden increase in the number of patients.4 As such, surge capacity should be quantifiable, at least in rough approximations, and should form an essential component of the preplanning process for mass casualty incidents. The challenges with the provision of such surge capacity metrics include a remarkable lack of consistency in what should be measured, how, and under what circumstances. The fact that the research which has occurred has been largely U.S.-centric may also provide some concerns regarding the ability to generalize the findings for use in other jurisdictions.5 Surge capacity is dependent on not only clinical treatment resources, but also on space availability, including regular in-patient beds of various types, critical care beds, availability of specialized treatment resources, such as operating theaters and recovery space, or treatment areas for contagious patients, and the logistics and supply chain resources required to support the expanded scale of care.6 Also critical to effective surge management are an effective Incident Management System, good communications, and both advance planning and response strategy development.

The need for surge capacity within a healthcare facility may be driven by a variety of different types of events. The most commonly examined is the mass casualty incident occurring outside of the facility, but which generates the unplanned arrival of large numbers of patients at the Emergency Department. A good example of this is the deliberate bombing of the Boston Marathon in 2013.7 It is generally assumed that most of these patients will arrive by EMS, but experience has shown that this is not always the case. In many cases, particularly during large scale events, it is not at all uncommon for victims to simply be loaded into private vehicles and driven to the nearest hospital, en masse, and with little or no advance notice. Following a large tornado strike on a heavily occupied trailer park in Alberta, Canada in 2000, by the time first responders arrived at the impact location and local healthcare facilities were actually notified of the incident, large numbers of patients were already arriving at their doors in private vehicles.8

A less commonly examined scenario which may drive the need for surge capacity is the outbreak of an infectious disease within a community. Such outbreaks may generate large numbers of actual patients, but they may also generate large numbers of individuals who are physically unaffected by the outbreak itself, but who worry that their rash or fever is an indication of infection. Such situations can create true challenges for the available assessment and treatment resources; all must at least be examined, and any actual infection ruled out by a healthcare professional, before they can be sent on their way, and all divert much-needed resources from those who are actually ill.

During the outbreak of SARS in several hospitals in Toronto, Canada, during 2003, the risk of infection to the general public was quite small; the disease was physically isolated within a small number of healthcare facilities.9 Nevertheless, literally thousands of “worried well” individuals lined up for assessment of symptoms, prompting the development and deployment of separate SARS screening and evaluation processes, to prevent Emergency departments from becoming overwhelmed. This necessitated the “up-staffing” of both physician and nursing resources, not only to deal with the numbers of patients in isolation, but also to provide the required screening and assessment of large numbers (some hospitals reported several hundred requests for screening per day!) of probably unaffected individuals. While this case involved the SARS coronavirus, an outbreak of pandemic influenza, such as the H1N1 variety recently experienced, or the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome virus,10 or an exotic disease outbreak, such as the Ebola outbreak in West Africa or COVID-19 worldwide, which are causing such concern at the time of this writing, have produced similar impacts on healthcare systems.

A final potential scenario driving the need for surge capacity is the large-scale contamination of individuals with hazardous materials. Such scenarios may be accidental in nature, or they may, sadly, be the result of deliberately caused events. Again, such incidents may occur with little or no warning, and there is frequently little guarantee that any decontamination of patients will occur prior to their arrival at the hospital. A deliberate release of the toxic nerve agent, Sarin, in the subway system of Tokyo, Japan during 1995, resulted in the secondary contamination of numerous physicians and nurses, as most patients had proceeded directly to the closest hospitals to their locations without being decontaminated. Of the more than 5,000 people who were injured, only about 150 were actually transported by ambulance.11

Ability to Handle Higher Than Normal Demand

The ability to cope with such demand clearly requires thinking which is “outside the box.” The normal methods of patient management and patient flow do not apply in such circumstances. This requires creative thought, however, as in many aspects of emergency management, the time to do most of the thinking is actually before the surge in demand for services actually occurs. Systems which implement such measures with the greatest degree of success have generally preplanned each measure extensively. There are essentially five ways of temporarily increasing treatment capacity; these are expediting patient flow, suspension of services, early discharge and bed management, use of nontraditional spaces as treatment areas, and the use of existing treatment spaces to expand clinical capability.

This approach is a logical extension of the process of triage for incoming patients. The traditional approach in any Emergency Department is to treat the most seriously ill or injured first. This may still apply in the actual Emergency Department; however, the establishment of separate, independent processes for the rapid treatment and discharge of those with minor injuries, as well as the rapid treatment and re-evaluation of those with moderate injuries, can also be established. Not only do such processes ensure that only the most serious patients actually occupy treatment spaces in the Emergency Department, they prevent the Emergency Department from becoming overwhelmed. This is essential for safeguarding precious critical care resources.

Under normal circumstances, a patient with a minor injury or medical condition might be seen and treated by an actual Emergency Physician and one or more skilled and experienced Emergency Nurses, but in this case, such resources are urgently required elsewhere. This type of patient could just as easily be assessed and treated by a Family Physician, Nurse Practitioner, or Physician’s Assistant and general duty nurses assisting with the emergency, or even simply by a nurse. While this may not be regarded as “ideal medicine,” it is certainly clinically appropriate. By ensuring that the most experienced and qualified practitioners and critical care nursing staff are not being asked to deal with minor injuries, those with both major and minor problems are treated more quickly, and fewer backlogs in the treatment process develop.

It is also appropriate to triage for access to required resources, whether diagnostic or treatment related. Just as triage was used to determine the order in which all patients are seen and assessed, it can also be used to determine the order of access to Diagnostic Imaging, Laboratory Services, the Operating Theatres, and critical care bed space. In such an event, it is unlikely that the Emergency Department will be the only treatment area in the hospital with the potential to become overwhelmed; all of the aforementioned locations are equally vulnerable, and each these areas can become a substantial roadblock to the throughput of patients when this occurs. The Emergency Manager would benefit from a cooperative process with both clinicians and representatives from each of these areas in which the process of patient flow during a surge scenario could be examined. The entire process of patient flow through the treatment process can be the subject of a Value Stream Map (VSM), in order to preidentify any potentials for delay or other vulnerabilities. Each of these can be subjected to the Root Cause Analysis process, in order to determine underlying causes, and hopefully, to be able to mitigate such problems in advance.

Planning for Surge

Advance planning for surge is about both the enhancement of existing resources, and the ability to become creative; in essence, to think “outside the box.” Both aspects of this process are important; however, there is a logical sequence to the process.12 Since the more radical methods of managing surge are, almost by definition, less than optimal care, it is essential that these are carefully developed and planned for, but then reserved for when they are truly needed. The first stage must always be to find methods to enhance and improve the production of those processes which are already used on a daily basis to enhance both service delivery and patient flow.

When one examines the process of the assessment, initial treatment, and admission of any emergency patient, it is clear that there is a logical “flow” to the process. That process must continue, and the challenge is to do so when the system is attempting to process numbers of patients which are far greater than normal. It may be useful to examine the entire process from the initial greeting and assessment to the arrival at the in-patient bed on a nursing unit. The Emergency Manager might consider the creation of a Value Stream Map which covers each step in the entire process. This will assist in achieving a precise understanding of the process involved, along with the resources and time required for each step, under routine circumstances, in essence, understanding what is normal. Given that most Emergency Managers in healthcare settings tend to come from nonclinical backgrounds, it is useful to obtain the support of clinical colleagues in this process. Those clinicians who participate in the facility’s Emergency Planning or Emergency Procedures Committee are logical candidates, since they have already been exposed to the emergency management process.

One may also examine the process by which patients are received, evaluated, treated, and admitted during a surge event. Once again, the creation of a formal Value Stream Map may prove useful. The increase in patient flow is the primary cause of “bottlenecks” within the process, and a Value Stream Map can assist the Emergency Manager in understanding where such “bottlenecks” are occurring. Once these have been identified, the Emergency Manager should consider the application of Root Cause Analysis to each bottleneck, in order to fully understand its precise etiology. To illustrate, is the delay in processing patients through the operating theatres the result of insufficient appropriate space, staff shortages, or instrumentation shortages or other supply chain issues? Is it occurring because the Recovery Room is full and cannot receive more patients? And what is causing the delays in the Recovery Room? Once one begins to understand both the process of patient flow and the problems which may adversely affect it, it becomes possible to anticipate potential problems and develop both procedures and processes with which to address them.

Hospitals are boxes of finite size, and before one can find space for the victims of the latest calamity, it is often necessary to create available space of various types. As a result, one must also consider the process of creating space for patients. This too will require thinking “outside the box.” The discharge of patients is normally a well-thought-out process, planned for days or even weeks in advance. It normally occurs with advance notice, and during business hours. When “surge discharge” must occur, it tends to be more chaotic, and with little advance planning and significant time pressures. The discharge of an in-patient at 2 a.m. is an entirely different situation from normal discharge, and even if the patient was already expecting to go home from their elective surgery “tomorrow,” in the minds of most, including those who must transport and care for them, it takes some time to get people and resources organized. This is equally true for patients who are expecting transition to a long-term care facility, or to care in the community. Those who provide such services typically have minimal resources and may have little, or even no, overnight staffing. So, while the hospital requires the bed immediately, the actual clearing of that bed can pose a considerable logistical problem.

In addition, the hospitals in many modern public healthcare systems are subject to the problem of inappropriate bed usage, in the common parlance, “bed-blockers.” In England, for example, a National Health Service spokesperson revealed to the media that on any given day approximately 6,000 acute care hospital beds were being occupied by patients who have no further need of acute care hospital beds, but either require placement in long-term care which is unavailable, require social care which they are waiting to access, or, in some cases, simply refuse to leave. In Canada, this problem is identified as a major issue in a position paper by the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians13 and identifies clear lines between those inappropriately occupying acute care beds and the ability of the Emergency Department to provide the throughput of patients on a daily basis. Similar issues are occurring in Australia and in Ireland.14 Interestingly, it has been noted that in healthcare systems which are predominantly private, or a public/private mix, including both the United States and Germany, this issue does not seem to occur as frequently. It might also be observed, however, that the vulnerable people who occupy hospital beds inappropriately in one type of system do still exist in the other type, but are probably more vulnerable, and likely to become additional emergency patients in any community wide event.

If ambulances must routinely wait for hours to transfer care to emergency departments on a daily basis, how does this bode for the ability to operate during a disaster? Simply put, if this particular patient load is as low as 10 to 15 percent of in-patient beds, a 200-bed acute care hospital has 20 to 30 in-patient beds which might be needed in a mass casualty incident, which may be unavailable for use, and that lack of availability is unlikely to be plainly evident anywhere but in the Emergency Department. Clearly, metrics such as length of stay and Emergency Room wait times must be of interest to the Emergency Manager operating in a healthcare setting; they may be important predictors of what might happen during a mass casualty incident, and stress the need to examine the patient flow in such circumstances, and the need for different ways of managing it. It may even be that when the changes to patient flow and special facilities and procedures proposed by the Emergency Manager for use during a mass casualty incident flow congestion on a daily basis, as well as during a crisis. Indeed, at this writing, some hospitals in both Canada and the United Kingdom have actually implemented their major incident plans in response to daily patient flow problems, although the degree of success experienced has not yet been reported. Continued experimentation and research is required.

Decanting the Hospital

In any type of significant emergency, new in-patients are likely to result. The truth is that, with few exceptions, most hospitals tend to operate at, or just below, their capacity. Indeed, in some jurisdictions, economic constraints have meant that local hospitals are actually operating beyond their planned for capacity, primarily because there are no other options. In reality, there are a variety of factors operating; some patients are occupying beds not because they urgently need a specific treatment (e.g., some elective surgery) but because they want it. Other patients may require ongoing care in a specific facility or the community, but may have been previously difficult to place. It has been estimated that in some jurisdictions, a significant percentage of total occupancy may fall into one of these categories.

One Canadian hospital corporation reported that 124 of 910 beds were currently occupied by so-called “bed-blockers,” with 49 patients on stretchers in their two Emergency Departments waiting up to 27 hours for admission to a ward.15 In the National Health Service in the United Kingdom, the entire system is in crisis, with ambulances waiting up to five hours to admit patients into Emergency Departments, because those departments are completely backlogged, and the hospital itself overwhelmed with in-patients who have no medical necessity to be there, but for whom alternate care is not readily available.16 It should be borne in mind that the situations previously described are current, normal daily operating levels, and not the result of mass casualty incidents.

Any surge in demand for services, particularly when it generates those patients requiring in-patient care, will place substantial additional pressure on both hospital occupancy and access to services. When the hospital in question is one of several operating in a region, it may be possible to distribute patients from whatever incident has occurred in a relatively even fashion, perhaps even by predetermined specialties, or to redistribute patients to other hospitals, once they have been initially assessed. But what happens when the hospital is the only facility in the area, or when surrounding facilities are so small that redistribution is not a reasonable strategy?

There is no escaping the fact that our hospitals are “boxes of finite size,” and that however much the community wishes to believe otherwise, there are limits to what each can cope with. In any type of surge event, it is likely that some patients will require discharge, in order to make space available to new patients who urgently require it. This process, called “surge discharge” should be an essential element of every hospital’s Emergency Response Plan, and is central to the successful development of surge capacity.17 Who then, can be discharged? In most respects, this is a risk management decision, and will require the cooperation and decision support of a physician for legal and liability purposes. Who are the likely candidates? Those new admissions for elective surgery are one potential group, although some care may be needed with this group, since this group is the most likely to “bounce back” as either urgent or even emergency surgical cases. Those for whom discharge is anticipated within the next 48 hours are another potential group; their treatment is largely complete, and they are probably quite safe to discharge. Those being discharged to care in another venue are also good candidates. Such individuals may be awaiting placement in a nursing home or other long-term care facility, or could possibly be going home for care in the community. In either case, if suitable arrangements can be expedited, these are excellent candidates to clear beds.

It is almost impossible to develop such “surge discharge” without substantial preplanning. Risk management decisions are required with respect to which categories of patients can be discharged, and in which order. The advance determination of levels of risk tolerance are essential. Specific guidelines will need to be developed for the guidance of those conducting the discharges, for both their protection and that of the facility itself. The decisions as to which patients fall into which categories will be made by professional staff, at the time they are required, and these too can be simplified through the use of simple, straightforward decision-support aids, and also checklists to support the assessment and discharge processes.

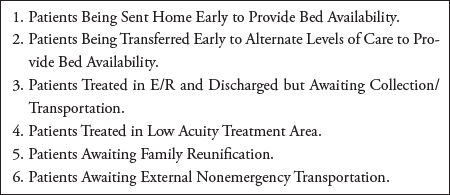

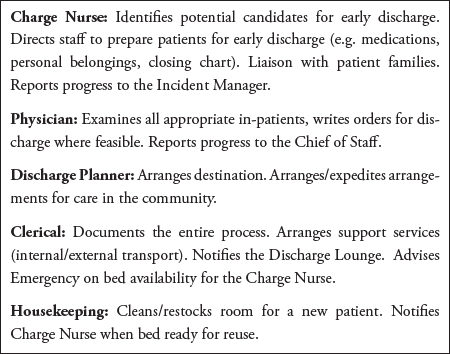

The “surge discharge” of patients should be an organized procedure; in some hospitals, all physicians who are not required for the treatment of patients in critical care areas report to the Chief of Staff’s office, or some other prearranged marshalling point. From there, multidisciplinary teams (in “IMS-speak,” a “Task Force”) are organized (physician, charge nurse, discharge planner, clerical, housekeeping) (see Figure 4.1) to go to each nursing unit and discharge all patients for whom this is a safe option, regardless of who is their attending physician. The charge nurse, who knows the patients best, identifies the potential candidates. The physician examines each and renders a decision, then writes any required discharge orders. The discharge planner makes arrangements for any support services required following discharge (and probably knows better than anyone else who the candidates for discharge are for the entire facility!). Clerical support is there to ensure documentation of the process and to notify attending physicians, families, and so on. Housekeeping will identify which beds require cleaning and reconditioning, and under which timelines. This process occurs at the direction of the Chief of Staff, and is agreed to in advance by the entire physician community, usually long before any emergency occurs.

Another method of enhancing the preceding approach involves the creation of a “Discharge Lounge” (see Figure 4.2) as a temporary surge management facility during the crisis. A safe and comfortable predesignated area, in a location adjacent to an exit door, is equipped with stretchers and wheelchairs, and staffed by a few members of staff who do not possess a critical care skill set. As patients are discharged from wards, they are brought, with their belongings, to this area to await the arrival of their families, or of the transportation services which will carry them to alternate venues of care. This rapidly clears the in-patient beds, permitting them to be quickly processed by Housekeeping, and making them available to relieve overloads of new patients requiring admission beds in either the Emergency Department or the Recovery Room. Such an approach can rapidly and dramatically enhance patient flow.18

Figure 4.1 The discharge task force

Figure 4.2 Discharge lounge candidates

Suspension of Services

The suspension of various types of services during a surge event may be one possible strategy for rapidly building capacity. It is, however, one method which requires careful advance assessment. To some extent, this will depend upon the type of service for which suspension is being contemplated. Some services cannot be suspended at all for clinical reasons; these would include clinically critical treatments, such as dialysis or chemotherapy. They would also include critical care services, such as Intensive Care Units (ICU), which are likely to be affected by the demand surge, in any case. It may be possible to suspend elective surgery, and while this will work for some types of procedures (e.g., plastics) it is likely that by suspending elective surgical procedures, at least some of those patients are likely to present at some point as “urgent” or even “emergency” cases.

When deciding to suspend services, a careful line of consideration is required. What will be gained by the suspension? Staff? Treatment space? In-patient beds? Other resources? If the suspension of a given service is unlikely to produce substantial additional resources with which to respond to the emergency, there is little point to the suspension. Who or what will be adversely affected by the suspension of service? To what extent? How will this occur? What is the timeframe before adverse effect begin to occur, or become problematic? Are there alternative operating procedures, such as the relocation of services to another site? Such decisions are not easy, nor should they be. All of these issues must be carefully considered, researched, tested, and addressed as an essential part of the development of any advance planning for the management of surges in demand for service.

Such procedures should be supported by specific formal procedures which have been developed in advance, complete with flow charts, step-by-step checklists, and other decision-support tools. This development can be assisted through the use of Value Stream Mapping to specify processes and identify potential problems. Root-Cause Analysis may also be required, in order to identify underlying causes of those problems for mitigation purposes. Finally, both Lean and Six Sigma will be required for the development and design of the actual process documents. Well-designed and thought out procedures, developed and tested in advance, can greatly aid in the decision-making process, and can also ensure that if such a measure is required, it is done correctly.

Nontraditional Space Usage

Hospitals have always dealt with surges in demand for service through the re-allocation of other spaces to patient care. Such spaces are generally common spaces within the facility. These can support operations such as secondary triage areas, temporary minor treatment areas, or temporary holding areas for patients awaiting actual bed space. The use of such spaces generally frees space in the higher acuity treatment areas, through the removal of those with relatively minor complaints to treatment in another venue. Such spaces may include lobbies, corridors, and even auditoriums. It may be entirely possible to create secondary patient flows, in which patients who are triaged with minor conditions are evaluated, treated, and discharged, without ever seeing the inside of the Emergency Department. Similarly, patients who are awaiting beds in the in-patient areas may be cohorted in another location until their actual bed is available.

Achieving this space usage requires advance planning, since such spaces usually have their own normal purposes, and will lack the staff and other resources which are required to repurpose them. A useful type of functional exercise in this process is called a TEWT (Tactical Exercise Without Troops), pronounced “toot”, which is a legacy from the time when most Emergency Managers were ex-military. Essentially, before war games, the officers in charge will generally walk across the “battlefield” and will determine starting positions for each of their resources, and will also determine what supports are required to place them in that position. Similarly, within a hospital, there is no reason why the Emergency Manager cannot, either singly, or with a committee, walk around the facility identifying potentially useful locations for emergencies.

Once such a space is identified and the role is selected, it is necessary to contact the “owner” of that space and secure a formal agreement for its use. It will then be necessary to determine what types of staff, with which skill sets, are required to staff such a location, and to determine where these staff are to be drawn from, in the event of an emergency. Finally, it will be necessary to determine what types of treatment resources other than staff are required, and to determine where those resources will come from, and how they will be obtained, both during and outside of normal business hours.

All of these resources should be secured by means of formal agreements. It is then necessary for the Emergency Manager to create a procedure, supported by a checklist, for the assembly and activation of each such space, with an objective of ensuring that the space can be successfully activated by even inexperienced staff, using the checklist. As with all good emergency procedures, such measures should be tested periodically and improved as necessary.

It is important to point out that some improvised measures can and should have a very short lifespan. While it may be necessary to cohort occupied stretchers in a corridor for an hour or two while awaiting the preparation of in-patient beds, such arrangements are very likely to be a violation of the hospital’s local Fire Code and associated regulations, for reasons of fire safety. While most fire departments will tolerate this usage for a few hours, a situation in which a corridor is still lined with occupied stretchers, with no admitting beds in sight two days after the incident has concluded, is liable to be cited for Fire Code violations. Also bear in mind that the space and the staff and equipment are all borrowed from somewhere else, and the best way to ensure their continued availability for future surge incidents is to ensure that they are returned to their rightful “owners” in at least as good a condition as they were delivered in. Such measures should be specifically written into the procedures and checklists designed for use in each space.

Redirect and Associated Problems

A common approach by hospitals to this problem in some jurisdictions is to attempt to automatically redirect all ambulances away from the facility, forcing them to transport patients to other, more distant facilities instead. While this sounds a little like “balanced distribution of patients,” in fact, it is not. In fact, when the Transport Officer at an incident scene, usually a paramedic, begins assigning destinations to those patients being transported, that destination assignment is based upon actually seeing and assessing the clinical status of the patient, and making a destination choice which is based upon the patient’s clinical needs and on the length of transport which the patient is likely to be able to tolerate. Distribution is balanced, based upon the patients’ needs, which are weighed against the need to avoid overwhelming a single facility.

When a hospital places itself on “redirect,” it is a blanket decision, with no consideration given to the clinical status of the patient, or the ability of the paramedic to manage that patient clinically, over a more extended period of transport. The paramedic has no option, and the patient has no option. Interestingly, if the same patient presented on their own at the emergency entrance, they would never be denied admission, for reasons of liability. While one may argue that the Emergency Department is overwhelmed, and there is a concern regarding patient safety, it can be equally argued that forcing a critically ill or injured patient to bypass a clinically appropriate hospital full of physicians and nurses and to be managed by a paramedic in the back of an ambulance for an extended period of time may also be patently unsafe, and perhaps more so than if the patient were accepted at the redirecting hospital. One particularly troubling issue is that the hospital generally has no idea whatsoever of the condition of the patients which it is turning away! There are even arguments in some quarters that hospitals which place themselves on redirect should be held liable for the ultimate outcome of any patients who are affected by their decision. Such an action may not occur immediately, however, from a liability and risk management perspective, it is an interesting and potentially concerning argument.

Surge Capability

A term which is just as essential to healthcare facilities, but less well understood, is surge capability. This term refers to the ability to handle patients who are presenting with problems not normally handled at a given treatment location. This term may also be understood to mean the use of existing resources differently, in order to provide expanded capacity for various types of treatment, during a surge event. To begin with, this includes the incorporation of contingencies which should already be present in the portion of the Emergency Response Plan which deals specifically with mass casualty incidents. Such resources would include temporary evaluation and triage areas, temporary minor treatment areas, or even temporary observation and holding areas for those patients awaiting in-patient beds. Such resources may be assembled in a hospital’s main lobby, the Outpatient Clinic, or even a corridor.

The use of such temporary treatment and holding areas can temporarily increase the treatment capacity of the hospital, and can prevent the Emergency Department from becoming overwhelmed by those with relatively minor complaints which could be treated elsewhere. This is not to say that the Emergency Department can no longer be overwhelmed, but with these measures in place, the problem will be with high acuity patients who actually need to be there, or with delays in the processing of those patients because of a lack of treatment space or resources elsewhere in the hospital. These issues are also an integral part of the surge capability issue, and this will be addressed separately.

Using Existing Resources Differently to Meet Demand

There are spaces within any hospital which could potentially be used to increase the capacity for the short-term management of high acuity patients. This is often a matter of redirecting the existing resources; however, this should be considered carefully, since there are often prices to be paid for such decisions. While the Emergency Manager will never be required to make such decisions, they must at least be understood, so that they can be offered as a potential option. Such discussions and problem-solving should occur in advance around a planning table, and not in the middle of a crisis. It is also useful to understand those problems which may occur as a result of these resource use decisions, so that their occurrence does not come as an unexpected surprise during a crisis.

In many mass casualty incidents, the management of patients can actually be considered as the management of the flow of those patients through a process, with various stages, including assessment, stabilization and initial treatment, admission, bed assignment, more comprehensive treatment, recovery and discharge. In such a system, there are four fundamental “choke points” in the processing of patients. These include the availability of diagnostic resources (particularly diagnostic imaging), Operating Theater space, Intensive Care beds, and general admission beds. Each of these “choke points” potentially presents its own solutions, and also its own problems, and each will be considered separately.

Repurposing Existing Treatment Areas

There are also locations within any hospital which may have existing resources and spaces which can be repurposed, in order to deal with a surge event. The first and most obvious of these is the Outpatient Clinic. This space can provide an excellent secondary assessment and treatment facility. Indeed, in many cases, particularly in older hospital buildings, the Outpatient Clinic was actually the Emergency Department at one time! This is a relatively common evolution of space usage, and often, useful resources such as medical gas outlets and emergency plugs even remain in place. Such a space, depending on how it is equipped and staffed, could provide an expanded Emergency Department space (particularly if they are adjacent), a minor treatment area, or even a critical care holding area.

Depending upon the size of the incident, the Recovery Room might be pressed into service as an improvised surgical intensive care holding space, while patients await beds in the actual ICU or await emergency transfer to ICU space in other hospitals. The equipment already installed in the space is certainly appropriate, and the staff who normally work in this location have the appropriate skill set. Care must be taken, however, to ensure that this use of space does not “cap” the availability of operating theater space; surgery, even emergency surgery, cannot commence until a space is available in the Recovery Room when the procedure has been completed! This strategy can work, but only in relatively small incidents with a limited surge in demand for surgical services.

Caesarean Section Suites are, for all practical purposes, operating theaters, and could be potentially pressed into service during a surge in demand for surgical services. To do so would require ensuring that the space was unlikely to be required for its original purpose over the short term. It would also be necessary to ensure that such an arrangement could be supported logistically, in terms of instrumentation, staffing, and Recovery Room support. Any type of repurposing of existing treatment spaces requires considerable advance planning, with all of the potential contingencies carefully considered, and well thought out, precise and tested procedures for repurposing developed in advance and incorporated into the Emergency Response Plan as an Annex. Much of such planning will be beyond the knowledge of the typical Emergency Manager, and such processes will require support and extensive input from both specialized clinical colleagues and those whose expertise includes logistics. The role of the Emergency Manager in such a collaborative process is that of expert facilitator and planner.

Always bear in mind that for many hospitals, the challenge in meeting a surge in demand for surgical services is only rarely about available space. Staff shortages, particularly in the earliest stages of a surge event and especially outside of normal business hours, can potentially be a problem. The largest single problem, however, is generally the availability of surgical instrumentation. Surgical instruments are expensive, and as a result, are often kept in limited inventories. Each item can only be used on a single patient, before it must be cleaned, resterilized and repackaged for use on the next patient. This process typically takes several hours, and, as a result, most surgery is performed during the day, with the instrumentation being “re-cycled” overnight, for use the next day.

Preparing for Surge

Repurposing Spaces

There are some issues related to the preparations to deal with surges in demand which must be addressed in advance, as opportunities present themselves.19 These may involve the use of specific spaces, the development of kits which permit the conversion of spaces to other uses, and the stockpiling of specific resources which may be required to address surge, but which are not required for use on a daily basis. Each of these provides specific challenges for a healthcare facility, and each will be addressed separately.

One factor which is rarely addressed is the use of “shuttered” hospitals or “shuttered” wings of active hospitals to house patients.20 Such spaces were often acceptable spaces in the past, and may be reused for this purpose, at least temporarily, in the future. This is generally a strategy for use in large, slow-moving emergencies, such as outbreak and epidemic scenarios, primarily because the activation of such a location for patient care requires considerable work, and so, is not appropriate for many types of mass casualty incidents. There are several challenges which must be addressed in order to adequately achieve this type of use. First, such structures must be habitable, and must meet Fire Code requirements. Second, building infrastructure, such as lighting, heating, ventilation, plumbing, and fire suppression systems must be functional.

The use of spaces which are not normally used for patient care or for conversion or repurposing for particular types of patient care will require advance planning.21 Some of these revised space uses will seem quite simple, while others will require more thought. The objective is to prevent the Emergency Department from becoming overwhelmed by patients who, while they may have legitimate treatment needs, can be a strain on resources while attempting to cope with abnormally large numbers of high-acuity patients.

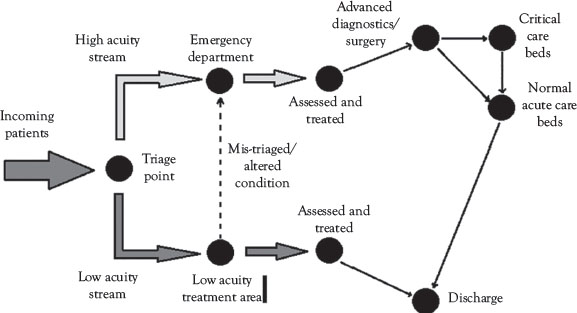

To illustrate, it may be possible to convert an Outpatient Department or a Family Practice Clinic into a low-acuity emergency treatment facility for the duration of the surge event. Some modern Emergency Departments already use a “Fast Track” approach to clear backlogs of low acuity patients, but rarely on the scale required during a mass casualty event. Indeed, some facilities in which overcrowding and long wait times for treatment may even discover that this approach will solve many of their day-to-day patient flow issues in the Emergency Department. During any mass casualty incident, it is never completely clear in advance what the distribution of patients by clinical acuity will be, but there will almost always be high and low acuity patients, as well as other patients who are not related to the disaster event. By creating a secondary, low-acuity stream from the point of triage (see Figure 4.3), it may be possible to divert 50 percent or more of all incoming patients to appropriate and safe care in a location which is completely away from the Emergency Department.

Figure 4.3 Diverting low-acuity emergency patients to secondary treatment options

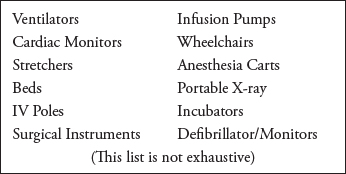

In most healthcare settings, care and assessment technologies evolve at a dramatic pace. In many circumstances, the expected useful life of various types of care technologies, medical electronics, for example, is typically about five years. This does not mean that five-year-old technology is going to the scrap heap; indeed, most of this type of equipment is sold back to the supplier when new equipment is purchased, and from there is reconditioned and resold to facilities in developing countries. This process applies to all types of medical electronics, and also to critical items such as ventilators and even beds and stretchers. While the equipment used on a day-to-day basis should remain current and state-of-the-art, there is little reason why equipment from one generation back could not be pressed into service in order to address surges in demand for service during a mass casualty incident (see Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4 Potential equipment to be recycled for surge

There are several arguments which support this approach. To begin with, the equipment in question was in recent use in the same hospital, and so little or no staff training in its use is actually required. The equipment is usually replaced on a “piece for piece” basis, and, as a result, the potential exists to be to essentially double critical care space when it is actually needed, without the long-term costs associated with doubling the size of those spaces on an ongoing basis. There are those who will argue that the hospital will lose the ability to apply the value of the old equipment to the purchase of the new; however, the amount of money paid for such used equipment is actually minimal. The reduction becomes particularly small if one adopts a policy of only retaining equipment “one generation back,” and of continuing to resell the third-generation technologies.

One valid argument raised regarding this approach is the normal lack of storage space within most hospital facilities. This is, in many cases, a matter of will. What is required is a reasonably sized space where all of this equipment can be stored appropriately with respect to temperature, dust, and electrical supply. Since there is a considerable amount of storage space required for various types of emergency management equipment, including kits for a triage area, minor treatment areas, the hospital Command Center, and so on, the approach would be to find a suitable multipurpose space; one which contains all of the appropriate space and resources, including security, but which could be quickly and readily accessed when the equipment is required. One could consider the purpose-built creation of such a space as any hospital redesign project, but in truth, the author has been in literally dozens of hospital basements, and rarely are such places without a suitable space of some sort, often disused and long forgotten.

Repurposing People

This is the third issue which must be addressed, in order to be able to deal effectively with surge. There are those who might argue that this is the most important barrier, but in truth, this is simply a matter of changing priorities. If one examines the types of facilities and “work-arounds” previously proposed, most of the resources required for them to become reality already exist in the facility, and simply need to be reapplied to the existing problem.

As one illustration, the notion of managing lower acuity patients in a separate patient flow stream requires staffing, but does it actually need to be the same type and numbers of staffing being used in the actual Emergency Department? No more than 20 years ago, the majority of Emergency Departments, particularly those located outside of large urban centers, were staffed by ordinary Family Physicians, not specialists in Emergency Medicine. In fact, most family practitioners have at least rotated through an Emergency Department as a part of their training. Since the expectation is to perform assessments and MINOR treatments, there seems to be no logical reason why such physicians (or for that matter, Physician Assistants, Paramedic Practitioners, or Nurse Practitioners) could not be used in this setting to provide appropriate care to lower acuity patients, thereby freeing actual Emergency Physicians and nurses to treat those patients who actually require that level of care. In the meantime, the potential risk for mis-triage is addressed, because the patient can simply be relocated to the Emergency Department if a problem is identified, or if their condition deteriorates.

Similarly, there is very little need for Registered Nurses to work in a Discharge Lounge, except, perhaps, in an oversight capacity. The very fact that such patients are being sent home or to a long-term care facility indicates that this level of care is no longer actually required. Depending on the types of patients, hospital auxiliaries, healthcare aides, or other volunteers could potentially operate such a facility safely and effectively, with a single Registered Nurse (R.N.) providing guidance for safety purposes. Hospital porter-ing, which has largely become a thing of the past in most hospitals, could be resumed, using support staff, thereby freeing actual care staff to take care of patients. What we are attempting to accomplish here is not best practice, but, rather, due diligence. Was a reasonable level of care provided in the circumstances, because that standard, and not best practice, is the standard to which the facility is most likely to be held accountable after the crisis has passed. The use of Pastoral Care and Social Workers to staff a Family Information Center is yet another example of nontraditional uses of staff in order to enhance the ability to manage surge.

Designing for Surge

In ideal circumstances, planning with the assumption that surge events are inevitable, rather than “something which might never happen,” can create the opportunity for the advance creation of specific contingencies.22 Such efforts may occur during new construction, or during the renovation of existing hospital spaces. Since surge events are somewhat infrequent, it is both logical and reasonable to begin with an assumption that those spaces which are specifically intended to accommodate surge will be multipurpose in nature. This may involve the creation of new infrastructure (e.g., construction of a new hospital or the redesign) and repurposing of an existing element of infrastructure (e.g. the decommissioning of an Emergency Department and its conversion to other uses). Either will involve specific input and direction to the project architect, since such provisions will rarely occur on their own.

Some design elements which can help to address surge include the inclusion of multiple building entrances to facilitate access, and buildings which have less floors, but are wider, which can reduce “bottlenecks” at elevators. The inclusion of large, multipurpose spaces can also help to address surge, as well as determining in advance what disaster facilities are required and incorporating dual-purpose features into other spaces being designed, such as deliberately building the hospital’s new executive boardroom so that it can be converted into the hospital’s Command Center, when required. In the United States, the Joint Commission on Hospital Accreditation offers specific useful advice and ideas on how to build for surge.

Conclusion

The management of surges in demand for services present a challenge to most healthcare facilities which is considerable, but not insurmountable. With careful consideration and consultation to support high-quality advance planning, such surges can be successfully prepared for and addressed. Of paramount importance is the clear understanding that the responses which occur are not simply “business as usual,” performed at a greater scale. The scope of practice for front-line staff may remain the same, but for the organization and its physical environments, business as usual is simply not possible; spaces and procedures will need to be adapted for completely different applications. Resources will need to be understood, so that they can be effectively used in ways which may bear very little resemblance to their daily operations. Surge management is about crisis management, and if foolproof methodologies for dealing with surge were available, the surge would not constitute a crisis.

Surges in demand for services can vary greatly; some will test one specific focus, such as the Emergency Department, while others will test other elements of service delivery. Surges in demand for services may occur quickly, as with a mass casualty event, or over a period of days or even weeks, as with a pandemic. Sometimes the need for surge capacity may be foreseen, while in other cases, it will come as a complete surprise. Each type of surge will be caused by a different source, and, as a result, most types of responses to surge will need to be case-specific. With the aforementioned in mind, it is entirely possible for a healthcare facility to prepare itself for, and then successfully respond to, any event which generates a surge in demand for services. The key to success is a well-developed and cooperative multidisciplinary planning and preparedness process.

The Emergency Manager operating in a healthcare setting is absolutely essential to this process. While the Emergency Manager will often lack a clinically based background, it is essential to understand, within a clinical setting, not only what is normal, but also what is possible. In such advance planning processes, the Emergency Manager must work in close cooperation with clinical colleagues, as well as those who manage both the physical space and the supply chains of the facility. Each has specific knowledge and skill sets to bring to the planning process. To illustrate, the clinical colleagues bring an expertise regarding both clinical requirements and normal operating requirements within the space being examined. While the Emergency Manager may not be a clinician, they can often provide an essential objectivity in the examination of potential for both changes to nonclinical procedures and space usage, which may have been lost by those who work in that environment every day. The major contributions of the Emergency Manager are as an objective set of eyes for the “subject-matter experts,” as a facilitator, and as a developer of both processes and procedures which are intended to provide a mechanism for responding to an abnormal situation.

Student Projects

Student Project No. 1

Select a currently used treatment space within your own hospital. In consultation with clinical staff, determine an appropriate use of this treatment space to enhance the surge capacity of your hospital. Conduct the appropriate research, in order to identify how similar space usage has occurred elsewhere, and to identify the resource requirements for such an improvised treatment area. Write a proposal for the inclusion of this space within the hospital’s Emergency Response Plan. Ensure that the document is suitably cited and referenced, in order to demonstrate that the appropriate research has occurred.

Student Project No. 2

Select a single group of hospital support staff (e.g., Volunteers) and explore methods by which they could be used differently in order to make other staff resources available for response to a mass casualty incident. Conduct the appropriate research, in order to identify how similar staff usage has occurred elsewhere, and to identify the process for implementing such improvised staff usage. Write a proposal for the inclusion of this staff usage within the hospital’s Emergency Response Plan. Ensure that the document is suitably cited and referenced, in order to demonstrate that the appropriate research has occurred.

Test Your Knowledge

Take your time. Read each question carefully, and select the MOST CORRECT answer for each. The correct answers appear at the end of the section. If you score less than 80 percent (8 correct answers) you should reread this chapter.

1. The term “surge capacity” may be defined as the ability of a hospital or other healthcare facility during a disaster to increase the:

(a) Number of patients receiving emergency care

(b) Scope of treatment available to patients

(b) Rapidly discharge in-patients to create bed space

(b) All of the above

2. The term “surge capability” may be defined as the ability of a hospital or other healthcare facility during a disaster to increase the:

(a) Number of patients receiving emergency care

(b) Scope of treatment available to patients

(c) Rapidly discharge in-patients to create bed space

(d) All of the above

3. The term “surge discharge” may be defined as the ability of a hospital or other healthcare facility during a disaster to:

(a) Number of patients receiving emergency care

(b) Scope of treatment available to patients

(c) Rapidly discharge in-patients to create bed space

(d) All of the above

4. During any crisis, such as a Mass Casualty Incident, the standard to which a hospital may be reasonably held accountable for patient care issues is:

(a) Standards of Practice

(b) Best Practices

(c) Due Diligence

(d) Accreditation Standards

5. In order to expand a hospital’s ability to provide care to seriously ill or injured patients, it is appropriate to pursue a policy of reconditioning and storing medical electronics and other essential equipment for:

(a) One Generation Back

(b) Two Generations Back

(c) As Long as Possible

(d) Both B and C

6. In order to plan effectively to address surge issues it is necessary to first:

(a) Understand normal patient flow patterns

(b) Understand day-to-day barriers to surge

(c) Revise the Standards of Care

(d) Both A and B

7. In many hospitals, the ability to effectively manage surge could be accomplished by means of:

(a) Repurposing Staff

(b) Repurposing Equipment

(d) All of the above

8. In order to understand both normal and crisis patient flow in the Emergency Department, it may be helpful to conduct a research process known as:

(a) Value Stream Mapping

(b) Time and Motion Studies

(c) Best Practice Analysis

(d) Root Cause Analysis

9. In the various command and control models used in healthcare facilities, a Task Force may be described as:

(a) Those running the hospital

(b) A subordinate, multidisciplinary group charged with a specific project

(c) The Command Group

(d) The General Staff

10. One potential method for the expediting of patient flow in a mass casualty incident is to create separate assessment and treatment streams from the triage point, based upon:

(a) Patient perception of need

(b) The nature of the event

(c) Clinical acuity and care needs

(d) All of the above

Answers

1. (a) 2. (b) 3. (c) 4. (c) 5. (a)

6. (d) 7. (d) 8. (a) 9. (b) 10. (c)

Additional Reading

The author recommends the following exceptionally good titles as supplemental readings, which will help to enhance the student’s knowledge of those topics covered in this chapter:

Barbera, J.A., and A.G. Macintyre. 2007. Medical Surge Capacity and Capability: A Management System for Integrating Medical and Health Resources During Large-Scale Emergencies, 2nd ed. United States Department of Health and Human Services .pdf document, www.phe.gov/preparedness/planning/mscc/handbook/documents/mscc080626.pdf (accessed February 17, 2015).

Florida Department of Health. n.d. “Hospital Mass Casualty Incident Planning Checklist.” .pdf document, www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/emergency-preparedness-and-response/healthcare-system-preparedness/_documents/fl-hospital-surge-plan-checklist.pdf (accessed February 16, 2015).

Oliver, C. 2010. Catastrophic Disaster Planning and Response, 190, New York, NY: CRC Press.

Surge Hospitals: Providing Safe Care in Emergencies. 2006. “Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations.” .pdf document, www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/surge_hospital.pdf (accessed February 17, 2015).