Chapter 2

Navigating workplace complexity

ORGANISATIONAL DEMANDS FOR AUTONOMY and interdependence are like the visible tip of an iceberg. The pressure to do more with less and the need to be flatter, leaner and more agile are all surface-level signs of a much deeper and pervasive culture and engagement crisis.

As mentioned in chapter 1, an astounding 87 per cent of leaders and managers cite culture and engagement as critical or urgent — symptomatic of an old power model struggling to maintain relevance in a new, increasingly connected paradigm.

One of the most compelling aspects of emergent trends and social technological advancement is that information now overflows on a scale beyond that which we can physically comprehend. The world today is a paradigm whereby federated leadership destabilises monopolies, and organisations are challenged to continuously innovate in order to maintain relevance.

Canadian-born architectural theorist and writer Sanford Kwinter explores this context in Far From Equilibrium — a 2008 book that tackles everything from technology, society, and architecture on his premise that ‘creativity, catharsis transformation and progressive breakthroughs occur far from equilibrium’. In his book, Kwinter asserts: ‘We accurately think of ourselves today not only as citizens of an information society, but literally as clusters of matter within an unbroken informational continuum.’

As the great composer Karlheinz Stockhausen once said, ‘We are all transistors, in the literal sense. We send, receive and organise [and] so long as we are vital, our principle work is to capture and artfully incorporate the signals that surround us.’

Social capital and community

In a few short years our online experience has shifted beyond mere two-way dialogue into a ‘social capital’ phase that has tremendous influence over the way we build brands, innovate products and manage reputations.

Community has become our currency. These signals usher us toward a world where, according to Jennifer Dorman in her ‘Engaging digital natives’ presentation, ‘knowledge, power, and productive capability will be more dispersed than at any time in our history — a world where value creation will be fast, fluid, and persistently disruptive. A world where only the connected will survive.’

To understand the nature of social capital and its impact on society, commerce and culture, we must return to the pre-internet era.

Can you remember how you researched ideas before Google, or mobilised the support of friends and peers around important issues before online social networks existed?

Many argued life was simpler, while early adopters describe the ‘old world’ as one-dimensional, and characterised by static, linear transactions where ideas were conceived, packaged, dispatched and consumed without interpretation or input.

While stakeholder engagement includes many nuances, according to social scientist and communications strategist Len Ellis (in Marketing in the In-Between: A Post-Modern Turn on Madison Avenue), marketing in the early twenty-first century has been dominated by two approaches, neither of which is visible to the naked eye. Ellis outlines these two approaches as:

The use of data to define and shape human affairs into machine-readable form and the effort to create and sustain ongoing two-way relationships with consumers. The former is arguably one way in which human life is subjugated to the regime of the machine; the latter is one way the individual may one day emerge from within the datascape.

Ellis goes further to say these insights suggest a postmodern perspective is needed to ‘reveal both the “kaleidoscope” of data and “raw immaterials” of relationships’.

Exactly how far have we come? The Internet of Things (IoT) is testament enough — that is, the connectivity of any device with an on and off switch to the internet (and/or to each other). World-leading information technology research and advisory group Gartner claim that by 2020 there will be over 26 billion connected devices — where the relationship will be between people and people, people and things, and things and things. This increasingly complex situation affects how we live and work, encompassing everything from mobile phones, refrigerators, wearable devices, washing machines — almost anything you can think of.

Table 2.1 provides further examples of just how far we have come, showing how we connect and collaborate has changed over time.

Table 2.1: Connection contrast frame

| Then | Now |

| Controlling | Cultivating and distributing |

| Regular consumption | Co-creation and DIY ‘maker culture’ |

| Institutionalism | Autonomy and self-organisation |

| Intellectual property | Sharing and co-ownership |

| Traditional campaigns | Crowdsourcing and movements |

| Producers of content | Producers of context |

| Shareholder value | Stakeholder value |

In the past ten years we’ve seen a paradigm shift in business towards cultures of connection and belonging, and an environment where the barriers that once inhibited culture and contribution are less frequent. Increasingly, companies recognise the need to include customers and stakeholders in the design and evolution of growth efforts, and this is a context where innovation is born from diffusion and value is dispersed.

The connection crisis

In 2008 Forrester Research’s Mary Beth Kemp and Peter Kim challenged the advertising industry in their white paper ‘The connected agency’. In the paper, the authors predicted the survival of agencies would be determined by their ability to evolve from ‘pushing advertising campaigns to nurturing communities of consumers and matchmaking them with brands.’

In what has since been realised, Kemp and Kim hypothesised that the business of the future will have ‘learned to connect itself’ with defined communities of consumers by cultivating insights into their behaviour as they interact.

As social technology continues to advance, our transactional relationships with communities continues to evolve toward a more socialised experience, forever changing the ways that we engage, create and share online. This new reality presents us with an interesting dilemma: is ‘being connected’ and ‘conversation’ really enough?

By the end of 2016, Facebook had nearly 2 billion monthly active users. While this statistic is difficult to contest, consider for a moment that these users also reject commercial intrusions into a place they consider ‘very personal’. In other words, the parameters for connection that define ‘friends’ and ‘doing business’ are being increasingly blurred, resulting in an annoying proliferation of content and advertising in users’ personal ‘feeds’, all the more annoying because they lack both context and relevance.

Therefore, despite its ubiquitous benefits, the way businesses use social media often fails to capture the overlapping, asymmetrical, semi-public nature of ‘real life’ in our local community — the community of our passions. Another way to view this argument is to ask the following: where is the value in environments that serve us content based on preferences and attributes of people to whom we have arbitrary connections, yet absolutely nothing in common? While Facebook’s algorithms, on the other hand, ensure popular posts — those posts people are passionate about — are often highlighted, regardless of the facts or truth within them. Social media is working harder to find the value in its content.

(Re)discovering the village

The more connected we become, the greater the need for real-time strategy in organisations. This presents both challenge and opportunity for business leaders — and a notable challenge is that responding to customers with highly personalised content in real time isn’t all that easy. As a result, even the most contemporary marketers find themselves hard-pressed to better understand how they can use these fleeting moments to their advantage.

Facebook’s 2009 partnership with the World Economic Forum in Switzerland signalled that the post-modern future is upon us. While a very early example by comparison to the world today, the event transposed online thought and content once relegated to a small physical setting to a world stage unencumbered by demography or geography that enabled forum delegates to poll random segments of Facebook’s then 150 million user base.

The result? A real-time pulse of what millions of people around the world were thinking and feeling at that precise moment, connected to a question of planetary import.

This act extols the ‘strength of weak ties’ — a theory first presented by Mark Granovetter in his 1983 article published in the Sociological Theory journal. According to Granovetter, networks of connected strangers can become a crucial bridge between clusters of strong ties (the people we know), highlighting how people react when healthy social reinforcement is in place.

Moreover, it reinforces the power of social networks to connect people, resources and ideas to drive creativity and innovation forward. As if to reinforce the law of diffusion it is a declaration of interdependence that celebrates an individual’s unique social identity, simultaneously presenting us with an invitation to belong to something bigger.

A paradigm shift is occurring towards community — a context where everyone participates, everyone contributes, and everyone belongs. We are moving toward another sociological tipping point — one that demands even greater context and meaning, and which implies the existence of an ecosystem of overlapping communities of passion, a mix of social and commercial transactions that is semi-public, semi-familiar, and a different experience for everyone.

The challenge born of this environment is to understand the capacity, emotions and activities of a situation (the context). It is real life in real time; an acute relevance delivered through personalisation and location logic that progressively transforms our binary interactions with the social Web.

For the status quo it is an invitation to transform — to embrace mess, complexity and variation as a daily way of working, and to live our lives in a ‘perpetual state of beta’.

Social and technological advancement is, therefore, in ways not possible before now, enabling everyone, staff and business leaders alike, to become a value creator within context — to co-own and-produce both story and outcome. This is an environment where personal and professional participation culminate in a reconnection to what is timely, relevant and authentic. I often refer to this ecosystem as a ‘new lens’ through which to see and experience life, where opportunity and innovation are interdependent and present us with new paths and narratives.

By virtue of being part of this ecosystem, we inspire new stories — an environment where contextual value is the natural by-product of participation. Understanding this fully is, in part, about learning how we can authentically drive content across channels and platforms to create new experiences.

Ultimately, as Helge Tennø highlights in his presentation ‘Context, value & the new marketing economy’, this understanding is about learning how we can ‘transform from being content producers to context producers’ — an ecosystem that celebrates the interdependent actions of people everywhere, striving personally and professionally to find meaning and a greater sense of belonging.

This involves a heroic celebration of the everyday, bound by a new currency that considers people’s lives. As evidence of what this future holds, consider how easy it is to mobilise and empower people of diverse culture, geography, passion, interest and opinion, to co-create value and competitive advantage. An example of this is the Techfugees movement — a social enterprise mobilising the international tech community to respond to the refugee crisis. Techfugees organises conferences, workshops and hackathons around the world in an effort to supply a pool of tech solutions and tech talent to NGOs working with refugees, and refugees themselves.

Hence, the ecosystem connects us to the information and communities that we need the most.

Conscious leadership begins with an openness to embrace mess, complexity and variation. It requires a departure from the command-and-control siloed model for business, towards an ecosystem that co-creates value for its entire spectrum of stakeholders.

Emergent leaders recognise that success is less about controlling fixed outcomes and more about enabling a continuous cycle of collaboration, innovation and realignment.

For ‘old-school’ managers, whose skills were wrought in a hierarchical and autocratic ‘top-down’ business era, the idea of co-creation can seem radical — even terrifying. As if coming out of a trance (or, as I say in chapter 1, after swallowing the ‘red pill’), for the first time they see the world for what it really is. They are confronted with the realisation that the skills and modus operandi that served them for years — that once gave them power — has become a noose around their necks.

Your leadership imperative

Consumers vehemently oppose lack of transparency of organisational politics and power. Consequently, the institutional Holy Grails of corporate responsibility, shared value and corporate reputation management are crumbling in the wake of new business models that imbue collective benefit and co-ownership.

In this context the usual risk management and pretence of care that shrouds these business functions gives way to an ecosystem that embodies higher purpose and creates authentic value, and that is not dependent on lacklustre social campaigns or costly conventional media to maintain relevance.

Co-creation is no longer an enterprise ideal but a leadership imperative — a prerequisite skill set for organisations seeking to build strong cultures that employees and stakeholders believe in. In essence, to drive successful change leaders must learn how to spark a cultural movement. And at the heart of every movement is a catalyst for change. To this end, sustaining a vibrant culture demands new thinking and a new operating model. This cultural model is not about performance measures and ticking boxes devoid of humanity, and instead starts when an organisation learns what lights its people up. These are the first steps in shifting your business from a toxic, unconscious culture where engagement fails, to an emergent culture of innovation and co-creation.

Moving from toxic to Emergent

Many leaders struggle to acknowledge problems within the culture of their organisations and the active role they play in exacerbating these problems. As they stare in the mirror at their own reflection, their fear of inadequacy and of looking incompetent in the face of uncertainty, and their inability to navigate a persistently disruptive social and economic landscape result in a toxic culture of blame and avoidance.

According to Dan Brown, ‘Only one form of contagion travels faster than a virus. And that’s fear.’ At the root of broken organisations, a deep-seated incongruence exists between people’s work and life that causes anxiety, pain and despondency. A major contributing factor to this problem is misalignment of values. It’s an individual problem that affects the wellbeing of the collective, and vice versa.

Understanding your relationship to this incongruence as a leader and, more importantly, identifying the cultural position and propensity of your organisation for co-creation and innovation, is a vital step towards enabling conscious leadership, and moving your business culture from toxic to Emergent.

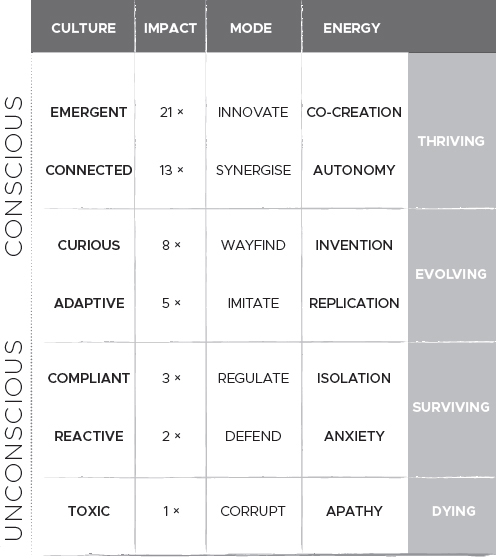

To help with this movement, I developed my Toxic to Emergent model (shown in figure 2.1), which outlines the various states of culture and modes of operation along this development. The model also outlines the energy and impact each stage creates.

Figure 2.1: Toxic to Emergent model

The model is divided into four key levels:

- Dying

- Surviving

- Evolving

- Thriving.

Culture in a business in the Dying or Surviving level is unconscious. As your business levels up, through Evolving and towards Thriving, culture becomes more conscious and, ultimately, Emergent. When an organisation learns to co-create, something extraordinary happens. Culture becomes less reactive and more conscious and adaptive, transforming as it levels up. Challenges still exist, of course, but the usual stress and fatigue of change is replaced with a new and vital energy that ripples throughout. I liken this evolution to Fibonacci’s spiral — an infinite cycle of innovation that results in exponential growth and impact (as shown in figure 2.1).

Let’s explore each level in more detail.