Chapter 4

Crisis at Enron Oil Corporation: 1987

Ken Lay was a good story. Natural Gas Week described the man “who hopped from Transco to HNG, and then had InterNorth for breakfast, even fooling some people into thinking that he was picking up the tab.” But this momentum was gone. The $70 per share buyout of HNG stockholders made for a happy ending, but the same transaction made for a precarious beginning.

At Lay’s insistence, InterNorth had overpaid for HNG by $5 per share, probably more. If everything had gone right, the premium could have been worked down. But the Peruvian nationalization of 1985, followed by the industry’s price collapse the next year—both of which had warning signs—made the acquisition’s high debt load lingering and constraining. Nonrecurring earnings were propping things up, not recurring, quality earnings.

In their first 19 months together, HNG and InterNorth recorded losses north of $100 million. Debt remained at over 70 percent of capitalization, which also meant higher interest rates than a better capitalized company would have paid. Speculative-grade “junk” bonds from Michael Milken’s Drexel became Enron’s debt instrument of necessity.

Still, Lay set a tone of high expectations. He announced the restructuring complete with the stock buyback and ESOP programs; his management team was mostly in place; and moral victories abounded. After all, wasn’t Enron the industry’s most innovative natural gas company? It was high time to have a big 1987 to support the (frozen) dividend, reduce debt, and achieve a credit upgrade, thereby creating a virtuous circle of lower interest costs and increased profitability.

The first quarter of 1987, the high season for natural gas, produced $67 million in earnings. The second quarter barely broke even, however, indicative of tough industry conditions and the company’s debt burden. Then came a ray of good news: a proposed recapitalization plan to reduce the debt ratio from 73 percent to 60 percent by year’s end.1 Enron’s stock, which had ended 1986 at $39.50, was trading at $51.00 nine months later in a down market. A ratings increase was under consideration by Moody’s Investor Service.

![]()

One profit generator being counted on for 1987 was Enron Oil Corporation (EOC), a 28-person oil-trading operation headquartered in Valhalla, New York, with offices in London and Singapore. The “flashy part” of Sam Segnar’s InterNorth, and now Lay’s Enron, was a company unto itself. EOC did not market for Enron Oil & Gas Company. Nor did it make trades related to physical infrastructure, as did Enron Oil Transportation & Trading (EOTT), a division of Enron Liquid Fuels run by Mike Muckleroy. EOC traded paper barrels of crude oil and just about any petroleum product; EOTT traded mostly physical barrels that were moved from one place to another. EOC’s arbitrage and speculation was profit for its own sake; EOTT was about logistics. And 1,400 miles—three hours by Enron jet—separated Smith Street in Houston from EOC’s headquarters just north of New York City.

EOC had reported profits ever since Segnar hired Lou Borget from Gulf States Oil & Refining Company in early 1984 to set up a trading shop for InterNorth. Earnings of $10 million in 1985 were followed by $27 million in 1986, the latter accounting for a third of Enron’s total profit for that year. And that was after paying bonuses to EOC of $3.2 million in 1985 and $9.4 million in 1986, as aggressive as any on Wall Street, and after absorbing such costs as company cars and limousine service, not to mention the fine caviar and champagne that were always on tap at the office. After all, there were many more good days than bad—seemingly.

John Harding, the head of Enron International, the parent of EOC, described Lou Borget to Enron’s board as the best in the business. Borget had an edge on price movements because of his special relationship with some leading OPEC officials, his boss explained. For his part, Borget wrote in a board report: “As done by professionals in the industry today, using the sophisticated tools available, [oil trading] can generate substantial earnings with virtually no fixed investment and relatively low risk.” And as explained in Enron’s 1986 Annual Report: “The volatile oil prices experienced during 1986 benefited earnings of [Enron Oil Corp.] as profits are generated on margins and on the skill of the trader, not on the absolute price of the product.”

Like virtually all trading houses, EOC operated under in-house guidelines limiting open or naked positions (long or short obligations not offset in the other direction). In this case, the maximum nonhedged position was eight million barrels, and any position had to be liquidated if its paper loss reached $4 million (equating to a $0.50 per barrel loss-limit on the maximum volume).

Rules limiting unhedged risk also limited the home run, making profitable trading a game of small ball and perseverance. An outfit like EOC might be expected to earn $3 million in a decent year or as much as $7 million in a banner one. But if it was not skilled and careful, a trading house could lose money too.

Ken Lay liked Louis J. Borget—just as Segnar did. Borget, a New York native, had overcome an abusive father and put himself through night school at New York University while working full time at Texaco. Borget was intelligent, articulate, and debonair. He strode well in social settings. Mick Seidl respected him too.

Plus, Borget was tough and persuasive under the gun. His traders were devoted to him. But best of all, in Houston’s eyes, he was a moneymaker. To Lay, Borget was just another smart performer like his other operating heads: Gerald Bennett (intrastate gas operations), Mike Muckleroy (liquids), Jim Rogers (interstate pipelines), and, soon, Forrest Hoglund (exploration and production).

Sirens and Denial (Valhalla 1)

Borget had a few skeptics. Early on, Howard Hawks of Northern Liquid Fuels warned his InterNorth superiors that Lou Borget might be rolling his losses forward. Speculative trading invariably had dry spells, and Borget never seemed to lose.

At Enron, Borget had one mighty skeptic: J. Michael Muckleroy. The two first met at a company management conference in 1986. EOC was reporting big earnings, yet Borget was strangely evasive when Mike quizzed him about it. Muckleroy had once been an active commodity trader for his own account and knew that it was a tough game. Trading orange juice futures in the early 1960s, he had made $1.2 million in two weeks, only to lose most of it over the next months. What seemed so easy—he had played a citrus freeze just right—turned excruciating.

Muckleroy gained respect for how price-driving factors could change unpredictably. He knew the pain of margin calls that forced him to liquidate open positions that just needed a little more time. Muckleroy finally quit his sideline when his wife threatened to leave him. He did not believe that anyone could be a trading Midas, much less Lou Borget.

How did EOC’s earnings stay so strong and for so long? This was not the regulatory arbitrage of the 1970s, when price-controlled oil could be traded up to its market level. Back then, almost all traders had been winners.2 But with oil decontrol in early 1981, hundreds of trading outfits had folded. Only the real pros remained, mainly those trading around their company’s assets, such as oil production and refining.

EOC was working in a volatile price environment, which created opportunities for big gains—and losses. But even the best traders have bad runs, Muckleroy knew. There just are too many acts of man and of God for moneymakers not to be moneybreakers on occasion.

But most of all, Muckleroy knew that self-imposed company trading limits scarcely allowed the type of profits that EOG was reporting. To achieve earnings that high, Borget’s traders would have to be consistently winning in marathon trading. Yet Borget described EOC’s niche as low risk, combining arbitrage gains (simultaneous buy and sell orders locking in a price differential) and sure-bet tips about where prices were headed. Seasoned traders had reason to doubt both stories: Arbitrage is small, hard money because sure things are difficult to come by.

Muckleroy’s Houston operation was actually larger and more global than that of EOC. EOTT’s oil traders had the pulse of the industry, and the whisper was that EOC was making aggressive bets. Muckleroy warned his boss, Mick Seidl, who as Enron’s president and COO presided over both Enron Liquid Fuels (EOTT’s parent) and Enron International (EOC’s parent).

Mick had been in the oil business from his days at Natomas. But, curiously, he was not responsive to the red flags that Muckleroy found alarming. The same was true of Ken Lay. Richard Kinder, now Enron’s general counsel, did not give Muckleroy a beachhead either. With Lay setting the tone, top management was content with what came through official channels: the audited and recorded profit, the result of Lou Borget’s consummately turning superior knowledge into superior returns.

Enron was lucky to have Borget, people thought. Any fuss about him was just one more case of company infighting—and at a target whose 1986 bonus was 50 times that of the complainant (Muckleroy). Plus, Muckleroy went too far when he brought his concern to New Yorker Robert Belfer, Enron’s largest stockholder and a board director, who until recently had run Belco. Muckleroy had broken the chain of command. He was not being a team player.

![]()

On Friday, January 23, 1987, alarm bells went off for David Woytek, Enron’s vice president of auditing and one of the corporation’s 21 officers. A New York bank alerted him about large wire transfers to secret international destinations for the personal account of EOC treasurer Tom Mastroeni, Borget’s right-hand man. Woytek alerted Rich Kinder, who alerted Borget’s boss, John Harding, the head of Enron International. The first Valhalla scandal had begun.

Investigation by Woytek found trouble. A member of Woytek’s team, John Beard, scribbled notes such as: “Misstatements of records, deliberate manipulation of records, impact on financials for the year ending 12/31/86.”

A meeting in Houston was quickly convened with Borget and Mastroeni in the hot seat. Seidl was traveling, so Lay presided.3 The CEO was in a tight spot. Lay simply could not do what he might have done in more prosperous times—and should have done, period. Enron’s (low) earnings were in danger of violating its loan covenants, and a confidence crisis could lead to a ratings downgrade, if not worse.4 This was a baby that had to be split, Lay decided.

Harding, to his relief, got a viable explanation from the two. The funny stuff was just a means to smooth earnings between quarters and even years—just as Enron executives had instructed him (Borget) to do. Bankers preferred steady, recurring earnings, and EOC had little trouble finding another trading house to perform a net-out transaction to shift costs and revenue as desired. In this instance, the intent was to get a solid jump on 1987 earnings, something that 1986’s success happily allowed.

Ken Lay nodded sternly but appreciatively when he heard this explanation. But Woytek and his auditing team were ready to drop the hammer. Several million dollars were missing, and internal audit had turned up what appeared to be criminal behavior. Worse, right before the meeting, they had discovered that a key document brought in by Borget and Mastroeni had been forged. The incriminating fund flows on the original copy obtained from the bank had been suspiciously removed. The two had to be fired, maybe prosecuted. The whole Valhalla operation had to be reaudited and closed or at least merged into EOTT.

Mastroeni gave a plausible explanation of the peculiarities, but there was just too much smoke not to signal fire. A recess was called. Beard and Woytek walked over to Rich Kinder, Enron’s top lawyer. “They just lied to you,” Beard complained. Kinder allegedly responded: “Well, if it was up to me, I’d fire them all right now.”

But then the meeting turned in favor of the visitors. Borget and Mastroeni got moral support from Harding and Steve Sulentic, both of Enron International in Houston. (EOC’s performance had meant bigger bonuses for them that might have to be returned.) Borget and Mastroeni argued for EOC and promised to do things differently going forward.

This was Lay’s call, and the CEO did split the baby. This should not have happened, Lay said. There needed to be income restatements between quarters and years to achieve compliance. The money in question had to be retrieved. Privately, Lay instructed Woytek to get an auditing team up to Valhalla to review everything. New controls and a new treasurer had to be put in place. This could not happen again, Lay told Borget and Mastroeni point blank.

Still, Woytek and Beard left the meeting feeling defeated. Muckleroy, upon hearing it all, was perturbed. Borget and Mastroeni could not be trusted. For his part, Lay shared his decision with key board members and moved on. This was the last thing that he wanted to deal with, but EOC had to be watched very carefully. Henceforth, EOC vigilance was Mick Seidl’s number-one priority with daily examination of positions. Finally, to examine things more closely, an Enron board meeting was scheduled for that summer at EOC’s offices at the Mount Pleasant Corporate Center in Valhalla, New York.

![]()

Valhalla 1 was far from over. Woytek’s on-location audit work was troubled from the start. Borget kept a tight leash on his unwanted guests, and his books came without documentation. Still, the auditors pressed, and just when Borget seemed cornered, Woytek got a call from Houston to disengage. The new plan, explained Seidl, was for Arthur Andersen to take over. As it turned out, Borget had called Mick, complaining that the audit was disrupting trading. There was a danger of not making plan, Borget said. Enron could not afford that, Seidl knew.

The Lay-ordered investigation found a variety of irregularities. Borget had sold a company car for his own account. There were secret payments to a fictitious M. Yass (code for “my ass”?) that in all probability went to Borget and Mastroeni. Some of the companies involved in the countertrades did not seem to exist. Mastroeni had once been sued by his bankers for fraud. Internal audit took the report to CFO Keith Kern, who did not seem to want to get involved. Despite Lay’s order, this was not something that people at the top of Enron wanted to confront—at least not yet.

Now engaged in Valhalla, Arthur Andersen also encountered roadblocks. Borget was not providing information, such as daily trading reports that could be checked against Enron’s trading limits. In fact, Borget and Mastroeni admitted that they had routinely destroyed the dailies. This was a damning story, but the Valhalla cowboys had Houston on their side, as indicated by one note from nice-guy Mick Seidl to Borget after a conference call between the parties:

Thank you for your perseverance. You understand your business better than anyone alive. Your answers to Arthur Andersen were clear, straightforward, and rock solid—superb. I have complete confidence in your business judgment and ability and in your personal integrity. Please keep making us millions.5

In April, Arthur Andersen presented its findings to the Audit Committee of the Enron board of directors, chaired by Robert Jaedicke, a Stanford business professor who would continue in this capacity through Enron’s solvent life. Andersen’s conclusions were hardly reassuring. EOC had “demonstrated the ability” to engage in unrecorded commitments. Although more improprieties had not been found, there could be no assurance that more did not exist.

Some board directors were uneasy, including Ron Roskens, one of the few InterNorth holdovers, who expressed his concerns. But ending the operation was not on the table, only Mastroeni’s part in it. Borget had evidently felt confident enough about his own standing to call Lay just before the meeting and personally plead for Mastroeni, saying that the operation could not work without him. When Lay saw that the discussion was going against Mastroeni, he stepped in. According to the minutes of the meeting, “Management [Lay, clearly] recommended the person involved be kept on the payroll but relieved of financial responsibility.” One source claims that Lay said: “I have decided not to terminate these people. I need their earnings,” as though all of EOC was under the gun, but there is no confirmed source for that impression or for that quotation.

According to Muckleroy, there also existed a letter composed by John Beard, Carolyn Kee (of Arthur Andersen), and David Woytek, with input from Muckleroy, that detailed findings of criminality and wanton disregard of company policy by Borget and Mastroeni. If that is true, the Enron board’s dereliction in not terminating EOC root and branch would itself seem to border on negligence. But the allegation may not be true as described.

In any case, Muckleroy said, these four were apparently content to feel that, should EOC implode, their exposé would serve to exonerate them as having made their best efforts at diligence. It was the whistle blow, the smoking gun, which any external investigation would surely uncover.

As it turned out, EOC would go into crisis, but the damage would be contained and the investigation internalized. Not until many years later, with Enron and Lay under the microscope, would the full story of Valhalla come out.

![]()

Dodging a bullet at the April meeting, and perhaps knowing that this was their best or last chance, Borget and Mastroeni and a few of their traders who were on the take put their clandestine operation into high gear. They were in a hole and had to get out of it—again.

Big bets outside of their trading limits had been made back in 1986, but a fortuitous jump in oil prices at year end helped paper over the problems. Now more rabbits had to be pulled out of the hat to keep reporting profits in the dailies that Mick Seidl reviewed every workday morning at eight o’clock. Things were not going well, and rumors were flying. Don Gullquist, Enron’s treasurer, was getting calls from his New York bankers about how EOC was “lighting up every trade on the screen.” Enron seemed to be on one side or the other of an inordinate amount of cargos.

The caviar and champagne remained on ice. The bets were scarcely winning. Long positions made at an average $21 per barrel had lost as oil prices fell, and short positions made at an average $19 per barrel went out of the money as prices rose.

To provide some cover for their growing limit violations, Borget went to Seidl with a request to increase their trading limits. Seidl put it on the agenda for Enron’s August board meeting in Valhalla. At that meeting, Borget made his case, comparing his risk profile to that of holding Treasury bills. Despite skepticism by a number of people in the room (attendee Robert Kelly described the presentation to his boss, John Wing, as “alchemy, selling fool’s gold”), the board voted to increase the open-position limit from 8 to 12 million barrels.

The verdict was decided before, not during, the meeting. Gullquist remembered how he and others on the plane ride up tried to move Ken Lay against Borget’s request. Lay ended this discussion by stating Enron’s need for earnings. As Lay went, so would the board.

Meanwhile, EOTT was hearing new rumors that EOC was on the wrong side of the market. More warnings by Muckleroy to the Big Three—Seidl, Kinder, and Lay—went unheeded, although Lay did phone Borget about the whispers to make sure they were not true. (Borget said absolutely not.) Muckleroy was “paranoid,” it was said in the chairman’s office.6

EOC was up some $12 million for the first half of 1987, the books showed. Thus it was not out of particular concern that Seidl on a New York swing set up a lunch with his star trader at the Pierre Hotel in New York City. It was Friday, October 9, 1987, about a year from when Muckleroy first complained about EOC and about nine months after Valhalla 1.7

Crisis and Cleanup (Valhalla 2)

At lunch, Seidl got shocking news. “I’ve got a big problem,” Borget stated, alluding to trading imbalances that were under water. “How big is it?” Seidl shot back. “I think it may be as much as $50 million before tax,” answered Lou. Borget confessed to busting through his newly increased trading limits but expressed optimism about winnowing his way out of the predicament with some time and support from corporate.

Mick was crestfallen. EOC was his responsibility. Lay had made it his number-one priority. John Duncan, who had dealt with sugar traders back at Gulf & Western, had warned him to be vigilant. (“Seidl, pay really careful attention. These people have a different mentality than everybody else.”) Mick had visited the large trading houses in New York and London to understand their systems and controls to get things right at EOC. He had worked hard at a professional and personal friendship with Lou Borget. This unit had never lost a penny. Its presentations were crisp and persuasive. The daily reports indicated another big year for Enron.

The deficit that Borget alluded to was enough to ruin Enron’s year—and cancel most, if not all, the profit that the EOC had made for Enron from its inception. And what if the hole was even deeper? Given the “screwy” things that had gone on at EOC, Seidl feared a worst-case scenario. Enron was just turning the corner—and now this.

After suggesting Borget do what he could to unwind the bad deals, Seidl jumped on his plane to intersect with Ken Lay, who was coming home from Europe. Lay and Seidl would return to Valhalla to meet with Borget, and Lay’s plane would return with its other occupants to Houston.

Lay had been touring Europe with Forrest Hoglund, the new chief of Enron Oil & Gas Company, in anticipation of taking EOG public. Lay had lured Hoglund, an industry star, away from Texas Oil & Gas Company. If Valhalla had blown up six weeks sooner, Hoglund might have stayed put.8

In Houston, Rich Kinder tracked down Muckleroy with the news. Kinder was no fan of Borget or EOC but had followed the leader on this one. He now had that cold feeling of financial doom—one he remembered from when some bad personal investments bankrupted him back in Missouri.

Muckleroy, previously the skunk at the lawn party, was now the company’s hope. He had experience. Get right to Valhalla with a team to unwind EOC’s positions, Kinder bellowed.

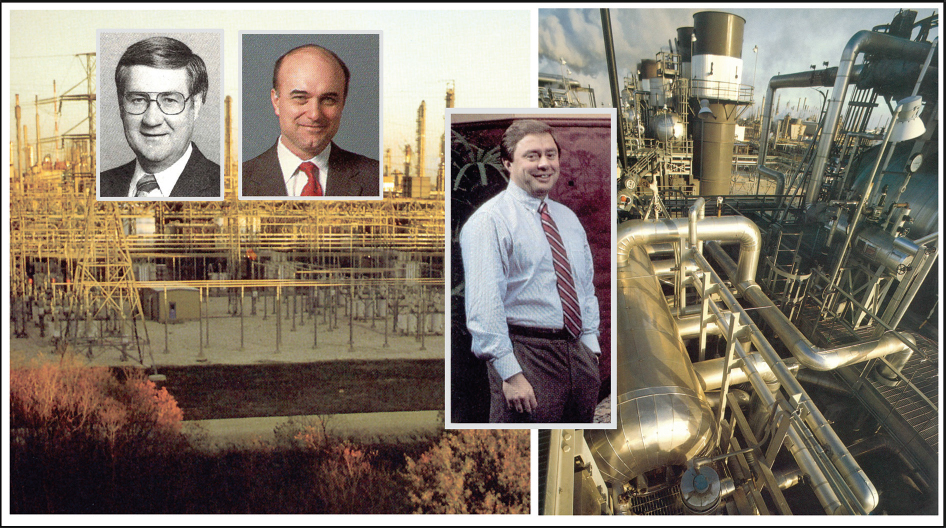

Figure 4.1 Head of Enron Liquid Fuels, Mike Muckleroy (upper left) futilely blew the whistle on Enron Oil Company’s Lou Borget (lower left). Muckleroy cleaned up Borget’s mess, a fiasco that was not fully appreciated until after Enron’s bankruptcy in late 2001.

Muckleroy was prepared. Having anticipated this crisis, he had a team on notice. The red alert was to pack for three weeks, wheels up in two hours. Joining Muckleroy were John Fetzer, EOTT’s most experienced trader, and Roger Leworthy, EOTT’s treasurer and credit manager. Internal audit and support staff would follow early the next week.

Muckleroy, in fact, had gotten Clint Murchison (the father of Florida Gas Transmission, among other pipelines9) out of a tight spot in the early 1950s, when an underwater pipeline owned by Delhi Oil broke near Corpus Christi, interrupting wintertime gas deliveries. The repair job by the former scholarship swimmer and Navy Seal earned special kudos from Murchison himself. Now, using every interpersonal and business skill in the book, Muckleroy had to save Enron by carefully unwinding a slew of out-of-the-money contracts without tipping off the market.

Muckleroy arrived at EOC’s offices in the early evening to find the employees in a daze. Friday trading was over. Many were in the dark about what was going on. Little had been done after Borget returned from lunch with Seidl. Borget had informed the floor of problems and had everyone in their chair pending Houston’s arrival.

Muckleroy first dismissed Borget, telling him to tell the floor and those who had to know that he was going on a two-week vacation, with EOTT running the office until his return. Other than that, he was to say nothing.10

Everyone else was likewise told to say nothing, not even to share trading positions with each other, or they would be fired on the spot. All communication would be centralized and come from the top—from Muckleroy. But there was a carrot. If everyone did as asked and performed well, each would receive a bonus and a letter of recommendation. It was a foregone conclusion that EOC would no longer be a going concern after the crisis passed.

After Borget, Muckleroy met with Mastroeni. His voice shaking, Muckleroy said:

Tom, I do not believe that you are the originator of what has happened, but you are certainly the facilitator. Borget is going to prison, but I’m giving you a choice. If you bring us the real books and help clean up this mess, I will do everything I can to keep you out of jail. If you flee, however, I will go to the ends of the earth to find you. And I want you to know that I have killed people in my [military] past and slept like a baby…. I’ll see you first thing tomorrow morning.

Mastroeni arrived at eight o’clock sharp on Saturday morning with two crates containing the off-the-books records. The salvage operation, what Mike Muckleroy would later call “the biggest poker game ever played in Crude Oil Trading,” was on.

The weekend was spent figuring out where EOC stood. The ugly truth was an out-of-the-money short position of 84 million barrels, not the feared worst-case scenario of 50 million barrels. Some 76 sham transactions had been made from as far back as November 1985 to hide the problems. No oil-trading house had been short this much, ever. As Enron would state in court documents, this short position was the equivalent of three months’ oil production from Britain’s North Sea fields.

The market could not be permitted to find out how badly Enron was in the hole. Credit cutoffs and margin calls would test Enron’s liquidity at the worst possible time, given that the bankers were in the middle of Enron’s recapitalization plan. All indications had to be business as usual—except that the ENE price was falling. Something was up, but no one at Enron would comment on why.

Monday began cautiously with Fetzer purchasing a few cargos and Leworthy working with Mastroeni to figure out EOC’s short position. The market saw that Enron was covering but little else. Still, losses of between $10 and $15 million were incurred in about five million barrels of unwinding.

With a few more million barrels purchased on the European market, Enron had covered some 10 percent of its open position. But early Tuesday morning, the bleary-eyed crew got a news flash: Iraq had attacked a supertanker carrying Iranian crude oil in the Strait of Hormuz. Oil in Europe was up over $1 a barrel, increasing Enron’s contract exposure another $100 million, or about $300 million overall.11

Then came Muckleroy’s finest moment. Tuesday morning, a half hour before the New York open, EOC offered one of the largest traders in the New York harbor market one million barrels at $1.25 over Monday’s close. This was a bold play. Enron needed to cover its obligated barrels, not sell new barrels, and any sale at this price would mean a large loss. Muckleroy had EOC make the same offer to other large houses before the bell.

The market got the message: Enron was not as short as believed. No one bought Enron’s cargo, thankfully, and the market opened less than a dime higher, which was even better. The bluff worked. Enron quickly bought two million barrels, followed later by some European cargo buys. One purchase was made from Shell International, which did not know that Shell USA had cut off credit to Enron on the rumors.

Enron had now covered 20 percent of its position at a manageable loss. It was hectic work, but the first laugh in days came when a trader asked Muckleroy what he would have done if Enron had had to sell cargos at the Monday close plus $1.25. “I would have just had to kill myself,” came his reply.

Credit was a worry. If Exxon cut off Enron as had Shell USA, the whole market would find out quickly, and Houston would be drawing down its lines. The bankers would find out everything, and oil sellers could name their price. Enron might even enter into a liquidity crisis. Ken Lay’s old employer held a sword over him, even if both he and the venerable oil major did not know it.

But Muckleroy had a high card to play. Enron Liquid Fuels had done a lot of business with Paribas ever since the merger. Philippe Blavier of Paribas particularly liked Mike Muckleroy, as did just about everyone. Mike asked Philippe for a $300 million line of credit, explaining that he was unwinding some bad positions and needed backup.

“What size position are you dealing with,” Blavier asked, only to add, “I don’t want to know, just tell me later.”

“Philippe,” Muckleroy replied, “I will explain it to you in 30 days over the best meal and finest bottle of Chateau Lafitte at the Four Seasons in New York City.”

Enron would owe Paribas that and a lot more, although the line would not have to be used. It made a world of difference for EOC just to be able to tell its trading partners to call Paribas if they needed a letter of credit in addition to the usual corporate guarantee.

The oil market calmed by midweek. Prices were within striking distance of most of the remaining open positions. It was now just a matter of buying cargos—but not too quickly. The loss was looking like $175 million—about $2 a barrel averaged over the entire short position. But there would be some offsets to the trading loss: $6 million of Borget bonuses that were in a deferred income account at Enron and a $15 million court-ordered award that would come from a Japanese trading company that participated in Borget’s ruse.

![]()

After 11 days, it was time for Muckleroy to return home. The scotch was flowing, and one of the Enron pilots kindly called Mrs. Muckleroy to come pick up her husband, although, yes, his car was at the airport. The EOTT team, with help from various Enron divisions, had lassoed the losses. EOC was now on a glide path to extinction.

Mike Muckleroy had just enough of an ego to look forward to getting back to the office. Would the Big Three look him in the eye? In particular, what would Ken Lay say? Lay had not once talked to Muckleroy during the ordeal, leaving that to Seidl. Seidl and Lay had stayed away from Valhalla; any sighting of these two would have charged the rumor mill.

The damage could have been worse. What if Mastroeni had not appeared with the real books on the morning of October 10, complicating efforts to unwind the positions and likely leading to the market’s learning about Enron’s huge naked positions? What if Exxon had cut off credit or Paribas had not extended a large credit line? What if oil prices had moved up several dollars per barrel? Maybe such a combination would not have sunk Enron—the company’s hard assets had a net market value north of a billion dollars before Valhalla. Unquestionably, though, recovery would have been much more difficult. And just maybe Ken Lay would have had to go.

Sanitization

The announcement came October 22: Unauthorized transactions in the oil-trading unit would result in Enron’s taking a charge of $142 million—$85 million after taxes—against third-quarter 1987 earnings. Net income for the company would be restated all the way back to 1984, the year that InterNorth hired Borget to set up EOC.12 The ENE share price, already down on rumors, fell on the official news for a total EOC-related loss of 30 percent. This was bitter medicine.

But what could be worse was a full explanation of the debacle. Public disclosure of Enron’s year-long civil war would stain Ken Lay in particular. ENE had always enjoyed a management premium centering on Lay’s aura of special talent. Should he be exposed as a pain-averse Big Thinker, his PhD credential would go from halo to Hamlet, and Enron’s board of directors would seem compliant with a fact-evading CEO.13

The press release, employee meeting, and follow-up interviews were exercises in half-truth. Enron had to tell a story but not fully. Corporations did this all the time, and certainly Enron had done this before, albeit on a much smaller scale. Press releases concerning the parting of a fired or demoted executive, for example, were typically half-truths (strategic deceit, aka philosophic fraud). And so it would be in 1991 when Transco fired CEO George Slocum (who back in 1984 took the place of departing Ken Lay as COO) but described it as his decision to leave—and only after great contemplation.14

The sanitized version of Valhalla went as follows. Oil trading is a secretive business depending on the integrity and highly specialized skill of the trader. The scandal was a classic case of unforeseen criminality where all signs pointed the other way. Lou Borget and Enron Oil Company were highly successful before the shocking turn of events, earning $50 million in two and a half years. There had been rumors, but every precaution had been taken. There were meetings, audits, and reaudits—and even an Enron board meeting held at EOC’s offices where everything was scrutinized.

During a period of unusual volatility in oil markets, the narrative continued, EOC got on the wrong side of a bet and tried to recoup the losses quickly, all the while violating company policy on both volume and margins. They went long and lost—and went short and lost again. To hide the deficits and violations of company policy, secret books were kept by EOC’s two most senior executives. But when the hole got too deep for the renegades, Enron was notified.

Enron found out on October 9—three days before the next scheduled audit—and acted quickly and prudently. Borget was fired, and the open positions were unwound in a matter of days. Enron’s full board, meanwhile, called into emergency session in New York City, shut down the unit as a going concern.

Enron was fooled but had been otherwise prudent. It was an “expensive embarrassment,” Lay told the New York Times. The business press, including a feature in Texas Business, portrayed Lay as shocked, dismayed, and helpless, given that, as the magazine described, “safeguards had been in place.”

Compliant analysts buttressed Enron’s whitewash. “How do you protect yourself?” asked David Fleischer of Prudential-Bache, an Enron investment bank that had recently sued HNG’s board over its payment of greenmail. “You’d have to hire an accountant and a marshal with a gun and have them peering over the shoulder of traders all day long.” But on closer inspection, a string of obvious management failures was behind the ruse of Borget et al.

![]()

“I promise you,” Lay told employees packed in the Hyatt Regency ballroom, “we will never again risk Enron’s credibility in business ventures without first making sure we thoroughly understand the risks.” At the meeting, Lay expressed his regret that several crooked employees could cancel out the profitable effort of thousands. As in golf, Lay analogized, Enron now had to scramble after a bad shot to make par.15

But wasn’t this the man who the year before told all that the business climate provided no margin for error? The man who just weeks before Valhalla 2 exploded told Forbes how much fun he was having with the disorderly market? Words aside, Ken Lay was an inveterate optimist—and a riverboat gambler.

Muckleroy left the employee meeting upset. He had expected a more forthright explanation and even contrition from the CEO. Instead, Lay professed total innocence. At one point, Muckleroy thought of standing up from his front-row seat and asking for the real story. But he was not going to embarrass the chairman, although two colleagues sitting on either side of him were ready to lean over to keep the peace.

Mike did get the real story out to the lawyers, which he supplemented with pages of hand-scribbled notes for the record. If heads were going to roll, he thought, it sure did not need to be his. He had been warned by a Vinson & Elkins attorney investigating the fiasco for Enron’s board: “Mike, never underestimate their ability for damage control.”

Others in the know were scared too. David Woytek duplicated all his papers for home storage. It could get ugly if Lay or another high-up needed to manufacture distance from the fiasco.

![]()

Muckleroy would never receive any one-on-one, heartfelt thanks from Lay, Seidl, Kinder, or Kern. But a layer down, Ron Burns, Forrest Hoglund, and others were congratulatory. Otherwise, the subject was over and done with—and verboten. In Lay’s mind, he had hired Mike, and Mike had come through—just another vindication of the smartest-guys strategy. It would not always have to be this way. Once Enron got its footing, such chances would not need to be taken again, Lay thought.

But a mea culpa, at least behind closed doors, was what was needed and entirely appropriate. “I was desperate for earnings,” Lay might have confessed to his inner circle and Muckleroy in particular. “Next time, I’m going to put Kinder on this and sooner—he is better with the hammer than me.” And finally, “Thank you Mike for your deft cleanup, and I apologize for downplaying your warnings.”

With the passage of time, Lay might have even revisited the issue for all employees. “I did not walk the talk about Enron’s core values when it mattered the most,” he could have admitted. “It is easy to look the other way or rationalize amid the pressure of earnings.” The lesson going forward: “Forbid shortcuts, and courageously solve problems before they get bigger and unmanageable.”16

As it was, Valhalla would soon be forgotten. It would be an afterthought when in March 1990 Enron filed suit against 21 plaintiffs, beginning with not only Borget and Mastroeni individually but also a raft of companies involved in the sham transactions and illegal transfers of money. Borget pleaded guilty to three felonies and was sentenced to a year in jail and five years of probation. Mastroeni pleaded guilty to two felonies but got only two years of probation after Muckleroy, as promised, pleaded for leniency.

Federal investigations did not find Enron liable, although the criminal defense lawyers, seeking to broaden blame, argued: “Any honest competent management, confronted with the conduct of Borget and Mastroeni, as revealed to Enron’s senior management in January 1987, would have fired these gentlemen without delay.”17

Costs and Consequences

Valhalla’s loss ruined Enron’s 1987. Paltry earnings of $6 million would be restated the following year as a $29 million loss. ENE’s fourth-quarter share price sagged from a high of $50.50 to a low of $31.00, before a year-end rebound to $39.125. Lay’s goal to end 1987 with a debt-to-capital ratio near 60 percent was eviscerated, although Enron’s recapitalization plan (which was completed only because the bankers were not alerted to Valhalla) resulted in a 70 percent ratio, slightly higher than the year before but still down from 1985’s 73 percent.

“Enron Is Upbeat Despite Poor 1987,” read a news item in Natural Gas Week. Valhalla aside, cash flow was significantly above 1986, the industry’s depression year. And take-or-pay liabilities were cut by more than half, from $1.1 billion to less than $500 million.

![]()

With the balance sheet wounded, it was necessary to sell a core asset, continuing the habit of monetizing good assets to pay for bad habits.18 Enter Enron Cogeneration Company (ECC), whose sale in part or in whole would help the income statement and balance sheet, at least in the short run. Cogeneration was a new technology and great new business for independents, thanks to political capitalism. With power-demand growth and the nuclear option closed after the Three Mile Island accident in 1979, many electric utilities needed new generation capacity. It all came together to create Enron’s highest rate-of-return business—and most marketable asset.

After ECC was reorganized, the inside-outside team of Robert Kelly and John Wing was able to redo the necessary contracts with Texas Utilities to get Texas City’s financing off the balance sheet. Fixed-priced, long-term gas was purchased from Enron Oil & Gas, a key modification that made the project bankable.

Project finance from a bank consortium was not the path chosen by Wing. Enron needed money fast, with 1986 drawing to a close. While negotiations with Texas Utilities were being completed to secure the contracts requisite for financing, Wing pushed forward with Drexel Burnham Lambert, already an Enron mainstay. Michael Milken’s company agreed to finance 90 percent of the project’s cost with high-yield junk bonds in return for a 50 percent equity kicker. The deal was done to help rescue Enron’s year after 1985’s net loss.

Wing cut several months off the usual process of bank financing and equity solicitation. But it was very expensive in terms of both the interest rate paid and the surrendered equity. More than this, though, the opportunity cost for Enron was having Harold Hawks in charge rather than consultant Wing. Hawks had put together the project initially. Hawks respected net present value economics. Enron, as it was, neutered not millions of dollars but tens of millions in its hurry.19

Texas City began full operations in May 1987. Wing collected a $1.5 million bonus, based on assured payouts, as well as a cut of the plant’s future profits. The plant was technically sound and highly profitable. Three years after start-up, Ken Lay and Rich Kinder would tell shareholders in Enron’s annual report: “Our state-of-the-art facility in Texas City has established Enron as a key player in this new market.”

Indeed, Texas City was a triple win for Enron. HPL carried 75 MMcf/d of gas to the plant. And EOG, supplying two-thirds of the gas to the operation, got a company-building contract far above the going spot price for gas, which the quirks of avoided-cost regulation under a federal law afforded at the expense of captive utility customers.

The genesis of EOG’s sweetheart contract came when Wing, after failing to interest Ted Collins at EOG, contacted Boone Pickens, who had recruited him to join Mesa Limited Partnership (formerly Mesa Petroleum Company) after he left Enron as an employee to consult. Mesa was interested in providing long-term gas at a premium to spot for Texas City. But when Lay found out that Pickens (his nemesis since the Jacobs-Leucadia buyout) was about to get a piece of his own deal, Collins and EOG agreed to a multiyear fixed-priced contract for two-thirds of the plant’s requirements. That deal, paying $3.25/MMBtu plus a 6 percent annual escalation factor—compared to spot gas just above $1.00/MMBtu—would prove invaluable for EOG and thus for Enron as gas prices remained low through the next decade.20

Enron needed more projects like this. But despite talk about new large projects (as many as six were in discussion), nothing had reached the construction stage. So in August 1987, in keeping with Lay’s way of doing things, Enron signed Wing to a new five-year contract, complete with a 5 percent equity interest in ECC. But Wing remained a consultant, not an Enron employee, although he could no longer work on non-Enron projects. It was a peculiar arrangement, but Wing was fiercely independent—and Enron’s own twists and turns were at work.

Figure 4.2 The PURPA-driven cogeneration work of John Wing (center) was a much-needed profit generator for Enron in the in the mid-to-late 1980s. Enron’s other two top cogen developers were Wing lieutenant Robert Kelly (upper right) and, from the InterNorth side, Howard Hawks (upper left), who would leave Enron in 1987 to found his own company, Tenaska.

The company Wing inherited had interests of around 400 MW in three cogeneration plants with a capacity of 915 MW, a portfolio soon supplemented by a 50 percent purchase of an operating 377 MW plant in Clear Lake.21 Arthur Andersen valued ECC for Enron at $30 million, giving Wing a $1.5 million stake at the get-go. But this valuation did not account for future projects, and discussions were under way concerning an additional 900 MW.

But come Valhalla, Wing’s new instruction was to sell part of his unit to improve the balance sheet and to create earnings.22 Lay blamed it on the oil-trading losses and more specifically, to the surprise of Wing, on the oversight failures of Mick Seidl and Keith Kern regarding Valhalla. In any case, Enron’s and Lay’s relationship with Wing was ruptured, and the future income from one of Enron’s top profit centers was halved.23 This cost from the oil-trading debacle would last for the rest of Enron’s life.

Lesson Unlearned

With his interpretation of Valhalla, Ken Lay fooled not only his employees, Enron’s investors, and general public. He fooled himself. The two-act scandal was chock-full of lessons. But by not volunteering the whole truth, by parsing it instead—a narrative that struck those closest to Valhalla as blatant lying—much instruction in bourgeois morality went undone. Scarcely realized at the time, the episode was “the canary in the coal mine” for what would ultimately bankrupt Enron and destroy Ken Lay professionally and personally.

Ken Lay—and Enron’s public relations team—committed philosophic fraud by engaging in half-truths, which philosopher Ayn Rand characterized as “a very vicious form of lying.” Not telling “the whole truth,” she explained, “is more misleading than simply lying, which is bad enough.” She continued:

It’s especially evil to claim honesty when you are deceiving somebody. This is why the oath you’re asked to take in court is so wise: You’re supposed to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

By condoning the well-documented indiscretions of Borget and Mastroeni, Lay also violated Adam Smith’s “sacred regard to general rules” and Samuel Smiles’s “path of common sense.” Classical liberalism’s wisdom of the ages applied to misjudgment at Enron.24

For more than a decade, Enron’s philosopher-king would not refer to Valhalla in his many presentations about Enron’s history.25 Had Lay forthrightly admitted how earnings-over-rules, ends-justify-the-means pragmatism had caused Enron’s “expensive embarrassment,” one that could have turned out far worse, humility might have been institutionalized for the good of himself and the company.

Instead, Lay began (or perhaps continued) talking the talk but not walking the walk. He would create safe harbors (such as a company vision-and-values statement) as if words trumped deeds.26

“Facts are friendly,” was one of Lay’s oft-repeated values. But the reality at Ken Lay’s Enron, even back in the 1980s, was “friendly facts are friendly.”

Almost 20 years later, commenting on Ken Lay’s conviction by a Houston jury and what was likely to have been life in jail, Enron whistleblower Sherron Watkins said: “Much of Ken Lay’s mistake was really continuing to let ethically challenged employees stay at the company if they were providing results.” That is what had happened, in bright lights, back in 1987.